Abstract

Background

Despite a recent American Heart Association (AHA) consensus statement emphasizing the importance of resistant hypertension, the incidence and prognosis of this condition is largely unknown.

Methods and Results

This retrospective cohort study in two integrated health plans included patients with incident hypertension started on treatment from 2002–2006. Patients were followed for the development of resistant hypertension based on AHA criteria of uncontrolled blood pressure despite use of three or more antihypertensive medications using medication fill and blood pressure measurement data. We determined incident cardiovascular events (death or incident myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke or chronic kidney disease) in patients with and without resistant hypertension adjusting for patient and clinical characteristics. Among 205,750 patients with incident hypertension, 1.9% developed resistant hypertension within a median 1.5 years from initial treatment, or 0.7 cases per 100 person-years of follow-up. These patients were more often men, older, and had higher rates of diabetes compared with nonresistant patients. Over 3.8 years of median follow-up, cardiovascular event rates were significantly higher in those with resistant hypertension (unadjusted: 18.0% vs. 13.5%, p<0.001). After adjusting for patient and clinical characteristics, resistant hypertension was associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.33–1.62).

Conclusions

Among patients with incident hypertension started on treatment, 1 in 50 patients developed resistant hypertension. Resistant hypertension patients had an increased risk of cardiovascular events supporting the need for greater efforts toward improving hypertension outcomes in this population.

Keywords: hypertension, epidemiology, incidence, prognosis, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Uncontrolled hypertension is one of the most important cardiovascular risk factors in the world today and contributes to an elevated risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and renal failure.1, 2 A recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) defined resistant hypertension as blood pressure that remains above goal despite the concurrent use of 3 different antihypertensive medication classes, one ideally being a diuretic, with all agents prescribed at doses that provide optimal benefit.3 Despite the recognition that these patients are a potentially higher risk subset, patients with resistant hypertension have been poorly characterized in the literature.

Prevalence estimates suggest anywhere from 3–30% of patients with hypertension require 3 or more medications to achieve blood pressure control.4–9 However, the incidence of resistant hypertension has not been well defined and has been defined as a priority area by the AHA.3 A greater understanding of the incidence and outcomes associated with resistant hypertension is important to improve the management of these patients. Prior studies on resistant hypertension are limited by failure to apply a uniform definition of resistant hypertension, lack of longitudinal blood pressure data and inability to identify “pseudo-resistant” hypertension due to poor medication adherence. Furthermore, the prognosis among patients with resistant hypertension compared to those without resistant hypertension is unknown.3

Accordingly, we assessed the incidence of resistant hypertension according to AHA definition among ambulatory patients with newly treated hypertension from 2 large integrated health plans based on hypertension medications filled, blood pressure measurements, and adherence data.3 Next, among a subset of patients without prevalent cardiovascular disease, we compared the risk of subsequent death, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and chronic kidney disease between patients classified as resistant hypertension and those with nonresistant hypertension.

METHODS

Study Population

The study sample was identified within two health plans within the Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN) hypertension registry from 2002–2006. The development of the CVRN hypertension registry has been described in detail elsewhere.10, 11 In brief, patients with hypertension at Kaiser Permanente Colorado and Kaiser Permanente Northern California were identified using a published algorithm consisting of ICD-9 diagnosis codes, blood pressure (BP) measurements (from non-urgent visits), and pharmacy data.12 The current analysis only includes patients with incident hypertension being started on an anti-hypertensive medication. Incident hypertension was defined as being a member of the health plan for at least 1 year prior to meeting criteria for the registry without any prior diagnosis of hypertension and without any prior pharmacy dispensing for anti-hypertensive medications (e.g., diuretics, B-blockers, ACE-inhibitors). Since the study inclusion and outcome criteria rely on diagnoses codes and pharmacy data, patients were required to have continuous health plan enrollment with pharmacy benefits for ≥1 year prior to and after cohort entry. Elevated BP was defined according to JNC7 thresholds of systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg with lower cut-offs of SBP ≥130 mm Hg or DBP ≥80 mm Hg for those with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease.13

Definition of Incident Resistant Hypertension

To define those patients who developed resistant hypertension during follow-up, the 2008 AHA criteria were applied. First, patients were followed forward (from time of starting one or more antihypertensive medication) to assess whether they were ever on 3 or more classes of antihypertensive medications for at least one month during the follow-up period. A 1-month interval was chosen to ensure persistent use of multiple anti-hypertensive classes. Patients on combination antihypertensive pills were counted as separate classes for each drug (i.e. thiazide diuretic and ACE-inhibitor). Patients were further divided into groups of controlled and uncontrolled hypertension based on their blood pressure nearest to the date of starting at least three anti-hypertensive medications. Hypertension control was based on current JNC-7 criteria.13

Next, the study cohort on at least 3 medications was followed for one-year to assess hypertension control, based on the blood pressure measurement closest to one year after starting 3 anti-hypertensive medications, and to assess adherence to anti-hypertensive medications. Among those who were controlled at one year, those on 4 or more medications were considered “resistant” and those on 3 or fewer medications were considered “non-resistant” consistent with guideline recommendations.3 Among those whose BP was not controlled at one year; those on less than 3 medications were considered “non-resistant” and those on 3 or more medications were considered “resistant”, consistent with the AHA statement.3 Patients without medication refill information over the follow-up interval were labeled as “indeterminate” and excluded from further analysis.

To further delineate those with “pseudo-resistance” (resistant hypertension due to poor medication adherence), the group of uncontrolled hypertension patients labeled as resistant was assessed for medication adherence during the year of follow-up. For each patient, a summary adherence measure was determined based on adherence (proportion of days covered based on pharmacy refill information) to each antihypertensive medication over the 12 month interval and then averaged across classes of medications. Patients with a summary adherence measure of less than 80% were considered non-adherent.14 Among patients whose BP was not controlled on 3 or more medications, those deemed non-adherent were re-classified as non-resistant for subsequent analysis.

Health Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality and incident cardiovascular events defined by non-fatal myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke or chronic kidney disease. For the primary analysis, the time to the combined outcomes of all cause mortality or incident cardiovascular events were assessed and patients with prior history of cardiovascular events prior to resistance status determination were excluded from these outcomes analyses. The presence of these conditions was determined based on ICD-9 diagnosis codes, problem list entries, and laboratory data according to pre-specified algorithms. Death was ascertained from internal health system databases and state death records. Primary hospital discharge diagnoses were used to identify incident cases of myocardial infarction (ICD-9 codes 410), congestive heart failure (ICD-9 codes 428), and stroke (ICD-9 codes 430, 431, 432, 433, 434, 436). Importantly, data on hospitalizations occurring outside of each health system were available through administrative claims data, which are considered highly accurate as they are used for reimbursement for out-of-system utilization. Both diagnosis data and laboratory measures of renal function were used to identify incident cases of chronic kidney disease. Patients with previously normal renal function were considered to have progressed to chronic kidney disease if, following cohort entry, they had a new diagnosis of kidney disease (ICD-9 codes: 585.1–585.9) or two consecutive estimated glomerular filtration rates less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation).15

Statistical Analysis

Among patients initially started on anti-hypertension therapy, rates of resistant hypertension were determined. Of the subset of patients started on 3 medications for at least one month, baseline characteristics were compared between patients eventually categorized as nonresistant (including those classified as pseudo-resistant) and resistant hypertension using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

For the primary outcomes analysis, among the cohort on 3 blood pressure medications for at least one month, freedom from the occurrence of the combined outcomes of death, non-fatal MI, congestive heart failure, stroke and chronic kidney disease were estimated for resistant and nonresistant patients using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients with prevalent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke or chronic kidney disease were excluded from this analysis. Freedom from an event was measured from the time of beginning three medications until a patient experienced the first event of interest or the study ended. Patients were censored if they were lost to follow-up. Differences in event rates were evaluated with log-rank tests. Next, multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed, adjusting for year of cohort entry, study site, and patient characteristics (gender, race, age, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol abuse, angina, asthma, atrial fibrillation, other arrhythmias, bipolar disease, diabetes mellitus, depression, drug abuse, migraines, peripheral vascular disease, schizophrenia and sleep apnea). In secondary analysis, we compared the outcomes of patients with resistant hypertension and patients without resistant hypertension (regardless of number of medications) within Kaiser Colorado.

In sensitivity analyses of the cardiovascular outcomes models, patients whose BP was not controlled at one year on < 3 medications who were also non adherent (N=1238) were excluded. These results were not significantly different and are not presented. Further analyses excluded those with pseudoresistant hypertension (N=269). Finally, since the chronic kidney disease outcome partially depends on the frequency of creatinine measurements, additional analysis excluded this outcome from the primary models to decrease the chances of surveillance bias. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The study was approved by the institutional review board of both health plans.

RESULTS

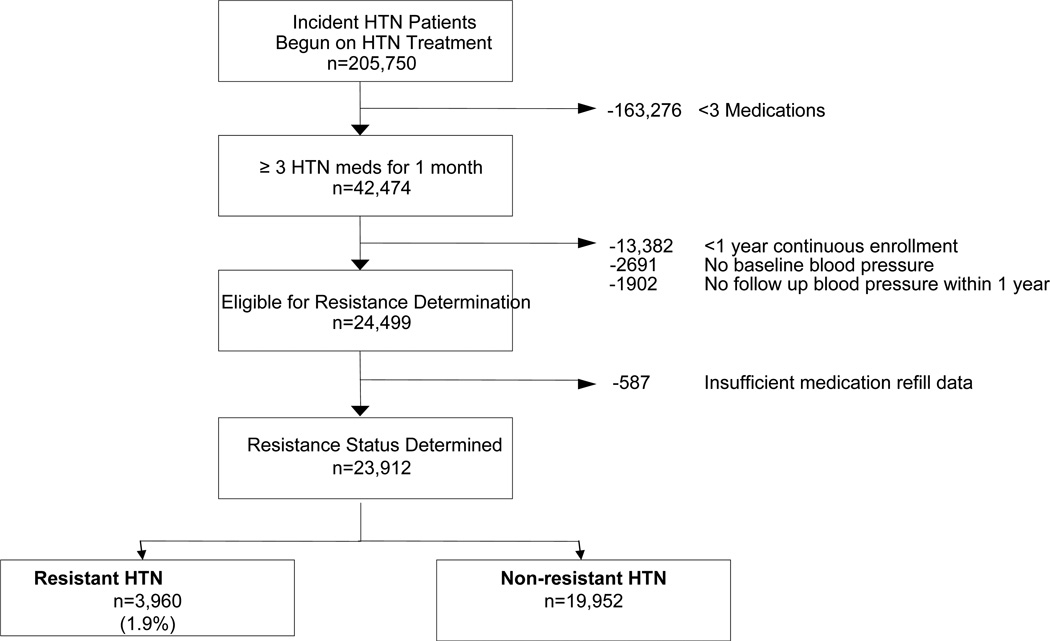

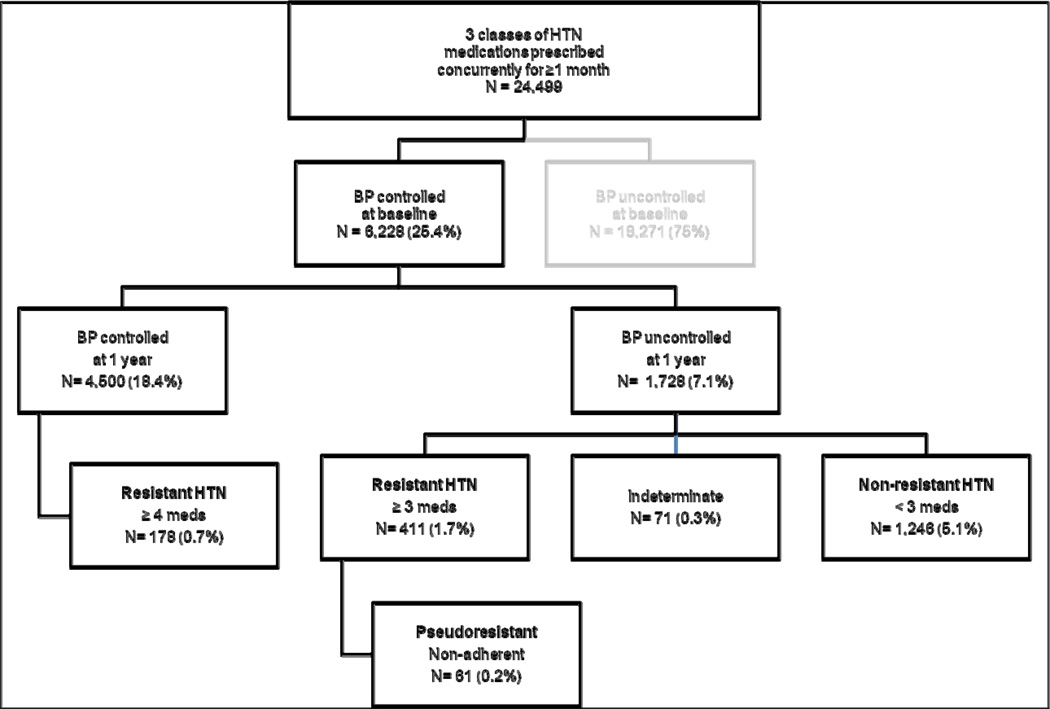

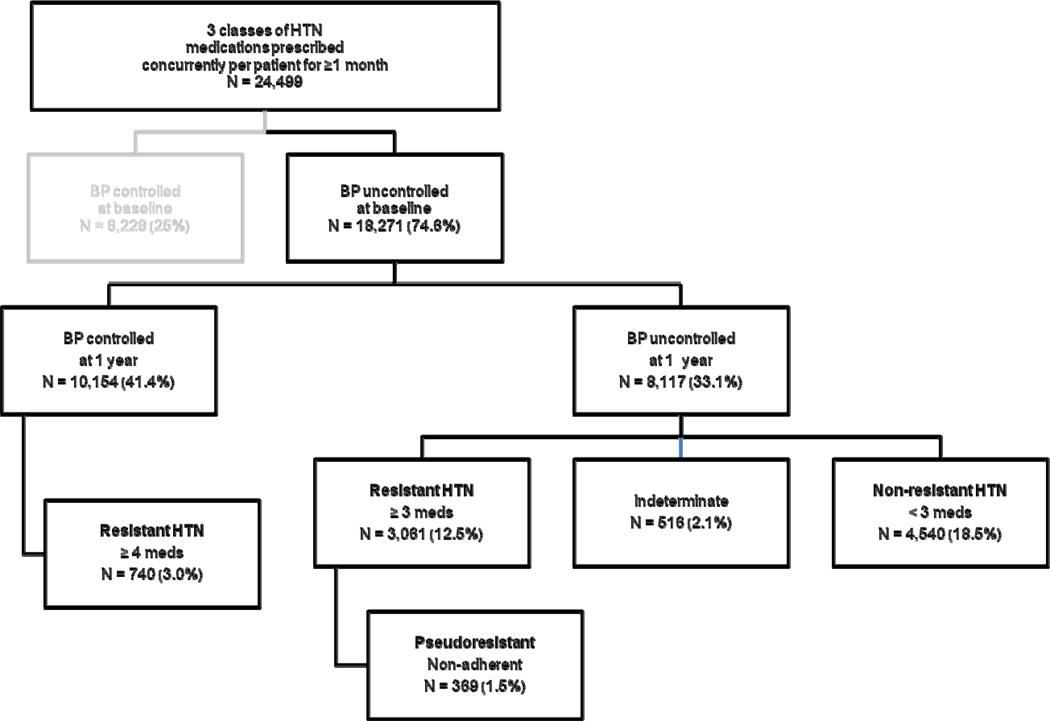

A total of 205,750 patients with incident hypertension were started on antihypertensive therapy. Of these, 42,474 (20.6%) were on 3 or more classes of antihypertensive medications concurrently for at least one month. An additional 13,382 (6.5%) patients were excluded due to lack of continuous enrollment for at least 1 year after starting 3 or more antihypertensive medications. Patients without a baseline blood pressure (n=2691) or a follow up blood pressure within one year (n=1902) were also excluded from further analyses. Our final study cohort included 24,499 patients who were eligible for resistance status determination. (Figure 1). Figure 2 a–b examines the 24,499 patients in detail according to their baseline blood pressure, follow-up blood pressure at one year and subsequent resistant status. For 587 patients, resistance status could not be determined due to lack of medication refill data during the follow-up interval leaving a cohort of 23,912 patients for whom resistance status was determined. Of those with uncontrolled hypertension at one year, a total of 3,472 patients were initially considered resistant based on number of medications; however 430 (12.4%) patients had “pseudo-resistant” hypertension due to poor medication adherence. Further, 918 patients were classified as resistant hypertension based on controlled BP on ≥4 medications. Therefore, 1.9% (n=3960) of patients from the original incident hypertension cohort on treatment (n=205,750) had resistant hypertension during a median 1.5 years (25th quartile 1.1years; 75th quartile 2.5 years) from initial treatment or 0.7 cases per 100 years of patient follow-up. Among those on 3 or more medications for at least one month (n=24,499), the prevalence of resistant hypertension was 16.2%. (Figure 2 a–b)

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study population.

Figure 2.

Determination of resistance status among those on 3 or more medications for at least one month.

a. Blood Pressure Controlled at Baseline

b. Blood Pressure Uncontrolled at Baseline

Those with resistant hypertension were more likely to be male, of white race, older and have higher rates of baseline diabetes compared to those with non-resistant hypertension (Table 1). Patients with resistant hypertension were more likely to be taking beta blockers (78% vs. 67%, p<0.001), calcium channel blockers (30% vs. 23%; p<0.001), and alpha adrenergic blockers (10% vs. 7%; p<0.001) than those with non-resistant hypertension, otherwise, medication classes for hypertension treatment were similar between the two groups. The rates of diagnosed secondary hypertension etiologies (aortic coarctation, Cushing’s syndrome, pheochromocytoma, and primary aldosteronism) were extremely low (<1%) and did not vary according to resistance status (data not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohort begun on 3 medications for at least 1 month according to their eventual hypertension resistance status.

| Characteristic | Resistant N=3,960 |

Non-Resistant N=19,952 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <.01 | ||

| Male | 49.6% | 44.9% | |

| Race | <.01 | ||

| Black | 8.2% | 8.3% | |

| Missing | 11.8% | 11.9% | |

| Other | 19.6% | 22.9% | |

| White | 60.4% | 56.8% | |

| Age* | 60.6 (60.2–60.9) | 58.7 (58.6–58.9) | <.01 |

| Baseline Systolic BP* | 153.4 (152.8–154.0) | 144.6 (144.4–144.9) | <.01 |

| Baseline Diastolic BP* | 84.4 (84.0–84.9) | 82.4 (82.2–82.6) | <.01 |

| Body Mass Index* | 30.8 (30.5–31.0) | 29.9 (29.7–30.2) | <.01 |

| Current smoker | |||

| Yes | 10.2% | 9.5% | 0.14 |

| Site | <.01 | ||

| Kaiser Northern California | 93.9% | 95.6% | |

| Kaiser Colorado | 6.1% | 4.4% | |

| Year of hypertension registry entry | <.01 | ||

| 2000 | 2.9% | 2.6% | |

| 2001 | 16.3% | 17.9% | |

| 2002 | 37.3% | 33.6% | |

| 2003 | 20.0% | 21.1% | |

| 2004 | 12.1% | 12.9% | |

| 2005 | 7.1% | 7.8% | |

| 2006 | 4.3% | 4.1% | |

| Baseline co-morbidities | |||

| Albuminuria | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.02 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3.6% | 3.5% | 0.87 |

| Angina | 0.8% | 1.1% | 0.14 |

| Asthma | 9.2% | 12.4% | <.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.9% | 2.0% | <.01 |

| Bipolar | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.24 |

| Coronary Artery Bypass | 0.7% | 0.7% | 1.00 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.9% | 1.3% | <.01 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 5.2% | 4.0% | <.01 |

| Diabetes | 17.7% | 9.6% | <.01 |

| Depression | 9.8% | 14.3% | <.01 |

| Drug abuse | 13.9% | 15.4% | 0.02 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.5% | 1.1% | 0.06 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1.9% | 1.4% | 0.02 |

| Sleep apnea | 2.0% | 2.3% | 0.42 |

| Stroke | 2.6% | 1.9% | <.01 |

| Baseline Hypertension Medications | |||

| Beta Blockers | 77.5% | 66.8% | <.01 |

| ACE/ARB | 69.1% | 69.8% | 0.43 |

| All Diuretics | 92.2% | 92.0% | 0.57 |

| K-sparing Diuretics | 35.0% | 36.0% | 0.08 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 29.7% | 23.4% | <.01 |

| Alpha Adrenergic Blocker | 9.6% | 7.4% | <.01 |

| Peripheral Vasodilators | 1.1% | 0.6% | <.01 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean and 95% confidence interval.

In the primary CV outcomes analysis, after removing patients with cardiovascular events prior to the resistant status determination date (n=5,876; 25%), a total of 18,036 patients remained. (Appendix 1) Over the median 3.8 years of follow-up (25th quartile 2.6 years; 75th quartile 4.8 years), 344 deaths occurred and the following numbers of incident cardiovascular events occurred, 90 non-fatal MI, 91 stroke and 53 congestive heart failure hospitalizations occurred. A total of 1,972 (11%) patients developed chronic kidney disease. In the unadjusted analysis, patients with resistant hypertension were significantly more likely to suffer the combined outcomes of death, MI, CHF, stroke or CKD (18.0% vs. 13.5%%, p<0.001, unadjusted HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.40–1.69). (Table 2) Following multivariable adjustment including baseline patient demographics, comorbidities, study site, and year of study entry, resistant hypertension was associated with increased risk of adverse CV outcomes (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.33–1.62, p<0.001). The proportional hazards assumption for hypertension status (resistant versus nonresistant) was met for the multivariate Cox model.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular outcomes among patients in the primary outcomes analysis according to resistance status.

| Resistant | Non-resistant | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Death | 54 | 2.1% | 290 | 1.9% | 344 | 1.9% |

| Myocardial infarction | 9 | 0.4% | 81 | 0.5% | 90 | 0.5% |

| Stroke | 15 | 0.6% | 76 | 0.5% | 91 | 0.5% |

| Congestive heart failure | 10 | 0.4% | 43 | 0.3% | 53 | 0.3% |

| Chronic kidney disease | 365 | 14.5% | 1607 | 10.4% | 1972 | 10.9% |

| Total Events | 453 | 18.0% | 2097 | 13.5% | 2550 | 14.1% |

| Total Patients | 2521 | 15515 | 18036 | |||

In secondary analysis using a referent group of all incident hypertensive patients (regardless of medication class number) compared to resistant hypertension patients at Kaiser Colorado alone (total n=16,963), patients who developed resistant hypertension (n=195) were significantly more likely to have adverse CV outcomes at any point over follow-up compared to those who did not develop resistant hypertension (53.9% vs. 14.5%; adjusted HR 2.49, 95% CI 1.96–3.15).

In sensitivity analyses that excluded patients with pseudo-resistant hypertension due to poor medication adherence (N=269), resistant hypertension patients remained at higher risk of adverse CV outcomes compared to non-resistant patients (adjusted HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.34–1.63, p<0.001). Finally, there was a trends towards increased risk of adverse outcomes with resistant hypertension when the development of chronic kidney disease was not included as an outcome (adjusted HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.98–1.43; p=0.09).

DISCUSSION

Among a large, community cohort of patients with incident hypertension begun on hypertension treatment, 1.9% developed resistant hypertension within a median of 1.5 years from initial treatment, or 0.7 cases per 100 patient-years. Patients with resistant hypertension were almost 50% more likely to suffer from a CV event over a median 3.8 years of follow-up compared to patients without resistant hypertension.

One of the most important contributions of this study is the estimate of the incidence of resistant hypertension. To our knowledge, our study is the first to show that among incident hypertension patients started on treatment, 1 in 50 will go on to develop resistant hypertension. Current estimates have focused on the prevalence of resistant hypertension and are based on cross sectional studies, international registries, claims databases or large clinical trials.3, 6–9 The 2003–2008 NHANES survey suggests approximately 12% of the antihypertensive drug-treated population met criteria for resistant hypertension.6, 7 A Spanish registry cohort similarly found 12.2% of treated patients with hypertension met criteria for resistant hypertension.8 Using claims data from over 5 million patients with hypertension, Hanselin et. al found that 2.6% were on 4 or more hypertension medications.9,4, 16 Data from clinical trials suggest 20–35% of hypertensive patients have resistant hypertension based on requiring three or more drugs to achieve BP control.17–19 For example, in ALLHAT, at the study’s completion, 27% of participants were on 3 or more medications; only 49% were controlled on 1 or 2 medications suggesting that over 50% would have needed 3 or more medications to achieve blood pressure control. Among our incident hypertension cohort initially begun on treatment (n=205,750), we found ~21% (n=42,474) were on 3 or more medications at some point over follow up. After considering medication adherence and blood pressure information, we demonstrated that only 16% (=3960/24,499) of patients on 3 or more medications continue to meet the AHA definition of resistant hypertension. Therefore, our study suggests the prevalence of resistant hypertension among those on multiple medications may be slightly higher than recent studies suggest.6–8 In contrast to prior studies, our study has the advantage of accounting for longitudinal blood pressure control and medication adherence using detailed pharmacy information among a large, community based cohort of patients with hypertension.

Another important finding of this study is the evaluation of prognosis of patients with resistant hypertension compared to those with non-resistant hypertension. Resistant hypertension was associated with a significantly increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events compared to non-resistant hypertension. Few studies have directly compared cardiovascular outcomes in those with resistant versus non-resistant hypertension.20 A small study (n=86) using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring demonstrated an almost 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events in patient with true resistant hypertension compared to those with hypertension responsive to treatment.20 We were not able to distinguish those with false resistant hypertension or white coat hypertension (high office BP but normal ambulatory BP), however, we also found an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events among patients with resistant hypertension based on office BP measurements. Differences in cardiovascular events in our study were largely due to the development of chronic kidney disease as defined by estimated glomerular filtration rates or diagnostic codes. While this definition is less restrictive than one based on the need for hemodialysis, patients with all stages of chronic kidney disease are known to be at higher risk for poor outcomes compared to those with normal renal function.21, 22 Together, these studies suggest that resistant hypertension defined by either ambulatory or clinic based BP measurements is associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes and represents an important public health issue. Future studies should investigate the prognosis of patient with resistant hypertension in other community populations.

Based on the current study, approximately 1 in 50 patients started on antihypertensive treatment will develop resistant hypertension within 1.5 years. In addition, we have shown that approximately 1 in 6 patients on 3 or more hypertension medications will continue to meet criteria for resistant hypertension over follow-up. Importantly, we have shown that adverse cardiovascular outcomes were significantly higher in those with resistant hypertension compared to those without. These findings are significant as the prevalence of resistant hypertension is expected to increase due to increased life expectancy and the increasing prevalence of factors commonly associated with resistant hypertension such as obesity, diabetes and chronic kidney disease.23 In accordance with the AHA statement, our definition of resistant hypertension incorporates blood pressure control as a criterion for resistance.3 Therefore, we are unable to distinguish whether the tendency towards worse cardiovascular outcomes is inherent to resistant hypertension status itself or related to blood pressure control. Whether the benefits of blood pressure control demonstrated in numerous hypertension clinical trials can be translated to patients with resistant hypertension is unknown and warrants further study.24–27

Certain limitations should be considered in the interpretation of the study results. First, this study relies on BP measurements from an electronic medical record. However, these methods for determining hypertension have been previously validated.11 In addition, as previously noted, this study uses office based BP measurements alone and ambulatory blood pressure measurements may provide more accurate estimates of resistant hypertension and have been shown to be more prognostic.8, 28 However, office based BP measurements reflect current practice and are used routinely in the management of hypertension. It is also possible that some patients in our cohort were misclassified due to the fact that we defined those whose blood pressure was not controlled on less than 3 medications as non-resistant. Some of these patients could be resistant with further medication additions; yet, our definition is based on the AHA scientific statement defining resistant hypertension and misclassification in this direction would bias our findings towards the null of no differences in cardiovascular outcomes between groups. Furthermore, the current study does not account for optimal dosing of each medication, the use of recommended drug combinations or require the use of a diuretic as defined in the AHA statement.3, 29 However, medication use and dosing in this study represent real-world management choices and over 90% of patients were taking a diuretic at the time of resistant determination. Further, we were unable to account for changes in body weight or patient salt consumption which are associated with resistant hypertension. In addition, the incidence and prevalence estimates in this study may not represent the true burden of disease due to the follow up timeframe available in the registry. With a longer follow up interval, the incidence estimates would likely increase. Finally, the findings in these healthcare systems may not be generalizable to other healthcare settings. However, these 2 systems care for almost 4 million patients in geographically distinct areas and the results for overall resistance rates were similar across sites (data not shown). Furthermore our population was drawn from an ambulatory population of hypertension patients seen in both primary care and subspecialty clinics whereas most prior studies have primarily studied resistant hypertension in subspecialty clinic populations.

CONCLUSION

In this cohort of patients from two health systems with incident hypertension, the rate of resistant hypertension was 1.9% within a median of 1.5 years from initial treatment. Further, approximately 1 in 6 patients on 3 or more hypertension medications will continue to meet criteria for resistant hypertension 1-year later. Importantly, patients with resistant hypertension were at higher risk for CV outcomes compared to those with nonresistant hypertension once patient demographic and clinical characteristics were taken into account. These findings support the need for greater efforts toward improving hypertension outcomes among patients with resistant hypertension. Future studies are needed to assess the prognosis of patients with resistant hypertension in additional community cohorts.

COMMENTARY.

The American Heart Association has defined resistant hypertension as blood pressure that remains above goal despite the concurrent use of 3 different antihypertensive medication classes. Despite the recognition that these patients are a potentially higher risk subset, patients with resistant hypertension have been poorly characterized in the literature. Among a large, community cohort of patients with incident hypertension begun on hypertension treatment, we found that 1.9% developed resistant hypertension within a median of 1.5 years from initial treatment, or 0.7 cases per 100 patient-years. In addition, we found that approximately 1 in 6 patients on 3 or more hypertension medication classes for at least one month will continue to meet criteria for resistant hypertension over follow-up. Patients with resistant hypertension were almost 50% more likely to suffer from a CV event (death or incident myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke or chronic kidney disease) over a median 3.8 years of follow-up compared to patients without resistant hypertension. These findings support the need for greater efforts toward improving outcomes among patients with resistant hypertension.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING SOURCES

The Cardiovascular Research Network is supported by a grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the NIH (U19HL91179-01). Dr. Daugherty is supported by Award Number K08HL103776 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Dr. Ho is supported by a VA career development award (05026).

Appendix 1: Baseline characteristics of study population included in the primary cardiovascular outcomes analysis (n=18,036)

| Characteristic | Resistant N=2,521 |

Non-Resistant N=15,515 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <0.01 | ||

| Male | 49.8% | 44.4% | |

| Race | <0.01 | ||

| Black | 8.1% | 8.7% | |

| Missing | 14.2% | 13.8% | |

| Other | 19.0% | 23.6% | |

| White | 58.7% | 53.9% | |

| Age* | 57.8 (57.4–58.3) | 56.6 (56.4–56.8) | <0.01 |

| Baseline Systolic BP* | 153.8 (153.1–154.5) | 145.1 (144.9–145.4) | <0.01 |

| Baseline Diastolic BP* | 85.7 (85.2–86.2) | 83.5 (83.3–83.7) | <0.01 |

| Body Mass Index* | 31.5 (31.2–31.9) | 30.3 (30.0–30.6) | <0.01 |

| Current smoker | |||

| Yes | 10.9% | 10.1% | 0.21 |

| Site | 0.04 | ||

| Kaiser Northern California | 95.7% | 96.6% | |

| Kaiser Colorado | 4.3% | 3.4% | |

| Year of hypertension registry entry | <0.01 | ||

| 2000 | 2.7% | 2.1% | |

| 2001 | 15.7% | 17.0% | |

| 2002 | 37.8% | 33.5% | |

| 2003 | 20.5% | 21.5% | |

| 2004 | 11.9% | 13.3% | |

| 2005 | 6.9% | 8.2% | |

| 2006 | 4.5% | 4.4% | |

| Baseline co-morbidities | |||

| Albuminuria | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.27 |

| Alcohol abuse | 4.0% | 3.4% | 0.13 |

| Angina | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.69 |

| Asthma | 9.2% | 12.5% | <0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.9% | 1.1% | <0.01 |

| Bipolar | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.86 |

| Diabetes | 16.4% | 8.2% | <0.01 |

| Depression | 9.8% | 14.0% | <0.01 |

| Drug abuse | 9.8% | 14.0% | <0.01 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.81 |

| Sleep apnea | 2.2% | 2.2% | 0.85 |

| Baseline Hypertension Medications | |||

| Beta Blockers | 77.7% | 65.4% | <0.01 |

| ACE/ARB | 67.9% | 68.6% | 0.43 |

| All Diuretics | 93.1% | 93.3% | 0.66 |

| K-sparing Diuretics | 36.7% | 38.2% | 0.16 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 28.0% | 22.6% | <0.01 |

| Alpha Adrenergic Blocker | 8.2% | 6.7% | <0.01 |

| Peripheral Vasodilators | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.05 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean and 95% confidence interval.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHBLI or NIH. Dr. Daugherty had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

DISCLOSURES

All authors report no conflicts on interest in regards to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawes CMM, Hoorn SV, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease. The Lancet. 2001;371:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. The Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, White A, Cushman WC, White W, Sica D, Ferdinand K, Giles TD, Falkner B, Carey RM. Resistant Hypertension: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117:e510–e526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, Margolis KL, Davis BR, Grimm RH, Black HR, Hamilton BP, Holland J, Nwachuku C, Papademetriou V, Probstfield J, Jackson I, Wright J, Alderman MH, Weiss RJ, Piller L, Bettencourt J, Walsh SM. Original PapersSuccess and Predictors of Blood Pressure Control in Diverse North American Settings: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2002;4:393–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.02045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN, Brzezinski WA, Ferdinand KC. Uncontrolled and Apparent Treatment Resistant Hypertension in the United States, 1988 to 2008 / Clinical Perspective. Circulation. 2011;124:1046–1058. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Persell SD. Prevalence of Resistant Hypertension in the United States, 2003–2008. Hypertension. 2011;57:1076–1080. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Sierra A, Segura Jn, Banegas JR, Gorostidi M, de la Cruz JJ, Armario P, Oliveras A, Ruilope LM. Clinical Features of 8295 Patients With Resistant Hypertension Classified on the Basis of Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. Hypertension. 2011;57:898–902. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanselin MR, Saseen JJ, Allen RR, Marrs JC, Nair KV. Description of Antihypertensive Use in Patients With Resistant Hypertension Prescribed Four or More Agents. Hypertension. 2011:1008–1013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho PM, Zeng C, Tavel HM, Selby JV, O'Connor PJ, Margolis KL, Magid DJ. Trends in First-line Therapy for Hypertension in the Cardiovascular Research Network Hypertension Registry, 2002–2007. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:912–913. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selby JV, Lee J, Swain BE, Tavel HM, Ho PM, Margolis KL, O'Connor PJ, Fine L, Schmittdiel JA, Magid DJ. Trends in Time to Confirmation and Recognition of New-Onset Hypertension, 2002–2006. Hypertension. 2010;56:605–611. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.153528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander M, Tekawa I, Hunkeler E, Fireman B, Rowell R, Selby JV, Massie BM, Cooper W. Evaluating Hypertension Control in a Managed Care Setting. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2673–2677. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.22.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating C. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, McClure DL, Plomondon ME, Steiner JF, Magid DJ. Effect of Medication Nonadherence on Hospitalization and Mortality Among Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang Y, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F for the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology C. Using Standardized Serum Creatinine Values in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Equation for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, O'Donnell CJ, Roccella EJ, Levy D. Differential Control of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure : Factors Associated With Lack of Blood Pressure Control in the Community. Hypertension. 2000;36:594–599. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Allhat Officers and Coordinators for the Allhat Collaborative Research Group. Major Cardiovascular Events in Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Doxazosin vs Chlorthalidone: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2000;283:1967–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Beevers G, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Ibsen H, Kristiansson K, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. The Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Marks RG, Kowey P, Messerli FH, Mancia G, Cangiano JL, Garcia-Barreto D, Keltai M, Erdine S, Bristol HA, Kolb HR, Bakris GL, Cohen JD, Parmley WW. A Calcium Antagonist vs a Non-Calcium Antagonist Hypertension Treatment Strategy for Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST): A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2805–2816. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierdomenico SD, Lapenna D, Bucci A, Di Tommaso R, Di Mascio R, Manente BM, Caldarella MP, Neri M, Cuccurullo F, Mezzetti A. Cardiovascular Outcome in Treated Hypertensive Patients with Responder, Masked, False Resistant, and True Resistant Hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1422–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fort J. Chronic renal failure: A cardiovascular risk factor. Kidney Int. 2005;68:S25–S29. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiffrin EL, Lipman ML, Mann JFE. Chronic Kidney Disease. Circulation. 2007;116:85–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pisoni R, Mustafa AI, Calhoun DA. Characterization and Treatment of Resistant Hypertension. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2009;11:407–413. doi: 10.1007/s11886-009-0059-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong H. Cardiovascular outcomes in the comparative hypertension drug trials: more consensus than controversy. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J-G, Staessen JA, Franklin SS, Fagard R, Gueyffier F. Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Lowering as Determinants of Cardiovascular Outcome. Hypertension. 2005;45:907–913. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000165020.14745.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staessen JA, Wang J-G, Thijs L. Cardiovascular prevention and blood pressure reduction: a quantitative overview updated until 1 March 2003. Journal of Hypertension. 2003;21:1055–1076. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. The Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salles GF, Cardoso CRL, Muxfeldt ES. Prognostic Influence of Office and Ambulatory Blood Pressures in Resistant Hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2340–2346. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gradman AH, Basile JN, Carter BL, Bakris GL on behalf of the American Society of Hypertension Writing G. Combination Therapy in Hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2011;13:146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.