Abstract

Objective

To examine associations between vasomotor symptoms and lipids over 8 years, controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors, estradiol (E2) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

Methods

Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation participants (N=3201), aged 42–52 at entry, completed interviews on frequency of hot flushes and night sweats (none, 1–5 days, 6 days or more, in the past 2 weeks) physical measures (blood pressure, height, weight), and blood draws (low-density lipoprotein [LDL], high-density lipoprotein [HDL], apolipoproteinA-1, apolipoprotein B [apoB], lipoprotein(a), trigycerides, serum E2, FSH) yearly for 8 years. Relations between symptoms and lipids were examined in linear mixed models adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors, medications, and hormones.

Results

Compared to no flushes, experiencing hot flushes was associated with significantly higher LDL [1–5 days: beta (β) (standard error (SE)) =1.48(.47), p<0.01; 6 days or more: β(SE)=2.13(.62), p<.001], HDL [1–5 days: β(SE)=.30(.18),; 6 days or more: β(SE)=.77(.24), p<.01], apolipoproteinA-1 [1–5 days: β(SE)=.92(.47), p<.10; 6 days or more: β(SE)=1.97(.62), p<.01], apolipoproteinB [1–5 days: β(SE)=1.41(.41), p<.001; 6 days or more: β(SE)=2.51(.54), p<.001], and triglycerides [1–5 days: percent change(95%CI)=2.91(1.41–4.43), p<.001; 6 days or more: percent change(95%CI)=5.90(3.86–7.97), p<.001] in multivariable models. Findings largely persisted adjusting for hormones. Estimated mean differences between hot flashes 6 days or more compared with no days ranged from less than 1 (HDL) to 10 mg/dL (triglycerides). Night sweats were similar. Associations were strongest for lean women.

Conclusions

Vasomotor symptoms were associated with higher LDL, HDL, apolipoproteinA-1, apolipoproteinB, and triglycerides. Lipids should be considered in links between hot flushes and cardiovascular risk.

Introduction

Vasomotor symptoms, or hot flashes and night sweats, are the cardinal symptom of the menopause and are experienced by most midlife women(1). Recently, links between vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular risk have been of interest. Although findings are not entirely consistent(2), there is indication from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)(3) and the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study(4) that the increased cardiovascular disease risk observed with hormone therapy (HT) use was particularly elevated among women with moderate-severe vasomotor symptoms at baseline, and in the WHI, the older women with vasomotor symptoms. We and others subsequently found vasomotor symptoms to be associated with increased subclinical cardiovascular disease indices, including poorer endothelial function(5, 6), higher aortic calcification(5), and higher intima media thickness(7).

Although there is interest in understanding mechanisms that may underlie any links between vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular risk, the current understanding of the physiology of vasomotor symptoms is incomplete. It is notable that women with vasomotor symptoms tend to have adverse cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and smoking, and psychosocial factors such as low socioeconomic position, depression, and anxiety(1). However, associations between vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular risk persist controlling for these factors(3–5, 7).

One potential link between vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular risk is lipid abnormalities. Findings from two cross-sectional, population-based studies indicate possible associations with vasomotor symptoms and an adverse lipid profile(8, 9). However, findings of links between vasomotor symptoms and lipids have not been universal, with several smaller studies showing null(10) or mixed findings(11). Thus, whether vasomotor symptoms are related to lipids remains unclear.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) provides a unique opportunity to estimate the relation between vasomotor symptoms and lipids. It allows examination of a range of lipid markers while controlling for relevant confounders in a community-based, multi-ethnic sample of women followed over time. We hypothesized that vasomotor symptoms, particularly hot flashes, would be associated with an adverse lipid profile. We examined this question among SWAN participants, who were assessed approximately annually for vasomotor symptoms and LDL-C, HDL-C, apoA-1, apoB, triglycerides, and lipoprotein(Lp)(a) over eight years. We controlled for relevant confounders, E2, and in secondary models, FSH. Finally, we examined interactions between vasomotor symptoms and menopausal stage, race/ethnicity, and body mass index (BMI), characteristics that may act as modifiers of these relations(7).

Materials and Methods

Sample

SWAN is a multiethnic cohort study designed to characterize biological and psychosocial changes over the menopausal transition. Details of SWAN design and procedures are reported elsewhere(12). Briefly, each SWAN site recruited non-Hispanic Caucasian women and women belonging to a predetermined racial/ethnic minority group (African American women in Pittsburgh, Boston, Michigan, Chicago; Japanese in Los Angeles; Hispanic in New Jersey; Chinese in Oakland area of California). Los Angeles, Pittsburgh and New Jersey sites used random-digit-dialed sampling from banks of telephone numbers, and Boston, Chicago, Michigan, and Oakland sites selected randomly from lists of names or household addresses. Select sites supplemented primary sampling frames to obtain adequate numbers of racial/ethnic minority women. SWAN protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at each site. Each participant provided written informed consent.

Baseline eligibility criteria for SWAN included being aged 42–52 years, having an intact uterus and at least one ovary, not being pregnant or lactating, not using oral contraceptives or hormone therapy, and having at least one menstrual cycle in the 3 months prior to the interview. 73% of the women selected provided information to determine eligibility; 51% (N=3302) of eligible women enrolled. Annual clinic assessments began in 1996–1997. This investigation was a longitudinal analysis of associations between vasomotor symptoms and lipids from baseline through the 7th SWAN visit.

Of the 3,302 women enrolled in SWAN, 92 women were excluded due to having had a reported stroke, angina, or myocardial infarction at baseline, and 9 women were excluded due to having no data for vasomotor symptoms or lipids. Data were censored during the follow up period at the time of hysterectomy/oophorectomy (n=221), and data from visits in which pregnancy or hormone use (hormone therapy (HT), oral contraceptives) within the previous year was reported were excluded. The 101 women excluded from this analysis had at baseline a higher BMI, more hot flashes and night sweats, higher anxiety and depressive symptoms, lower HDL-C, higher apoB, triglycerides, and Lp(a), and were less educated than women included (p’s<0.05). Primary models included 3,201 women.

Design and procedures

Vasomotor symptoms

Vasomotor symptoms were assessed using a questionnaire at each SWAN visit. Women responded to two questions, which asked separately how often they experienced 1) hot flashes and 2) night sweats in the past 2 weeks (not at all, 1–5 days, 6–8 days, 9–13 days, every day; categorized as none, 1–5, ≥6 days for analysis). Hot flashes and night sweats were considered separately due to their differential pattern of associations with lipids in this analysis.

Blood Assays

Phlebotomy was performed in the morning following overnight fast. Participants were scheduled for venipuncture on days 2–5 of a spontaneous menstrual cycle. Two attempts were made to obtain a day 2–5 sample. If a timed sample could not be obtained (as menstrual cycles became less regular, samples tied to the early follicular phase were less feasible), a random fasting sample was taken within 90 days of the annual visit. Blood was maintained up to an hour at 4°C until separated, frozen (−80°C), and sent on dry ice to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified CLASS laboratory at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor MI; E2) and Medical Research Laboratories (Highland Heights, KY; lipids, lipoproteins, and apolioproteins) for analysis. For budgetary reasons, lipid marker assays were completed at SWAN baseline and study years 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Lipid fractions were determined from EDTA-treated plasma(13, 14). Total cholesterol and triglycerides were determined by enzymatic methods (Hitachi 747 analyzer; Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). HDL-C was isolated with heparin-2M manganese chloride(13, 14). LDL-C was calculated by the Friedewald equation(15). Apo A-1 and apoB were measured by immunonephelometry (BN1A-100; Behring Diagnostics, Westwood, MA) calibrated with a World Health Organization traceable standard(16). Triglycerides and Lp(a) were natural log transformed for analysis.

E2 assays were performed on the ACS-180 automated analyzer (Bayer Diagnostics Corporation, Tarrytown, NY) utilizing a double-antibody chemiluminescent immunoassay with a solid phase anti-IgG immunoglobulin conjugated to paramagnetic particles, anti-ligand antibody, and competitive ligand labeled with dimethylacridinium ester. The E2 assay modifies the rabbit anti-E2-6 ACS-180 immunoassay to increase sensitivity, with a lower limit of detection=6.6 pg/mL and inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation of 10.6% and 6.4%, respectively(17). Duplicate E2 assays were conducted and results reported as the arithmetic mean. FSH assays were performed using a two-site chemiluminometric immunoassay, with inter-and intra-assay coefficients of variation of 11.4% and 3.8%, respectively, and lower limit of detection=1.1 mIU/mL. E2 and FSH values were natural log transformed for analysis.

Covariates

Race/ethnicity (determined in response to: “How would you describe your primary racial or ethnic group?”) and education (< vs. ≥college) were obtained in the SWAN screening interview. Age, smoking status (current vs. past/never), depressive/anxious symptoms, physical activity, alcohol use, menopausal status, and medication use/health conditions were derived from standard questionnaires and interviews administered during annual visits. Age, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, BMI, menopausal status and medication use/health conditions were considered as time varying covariates. Physical activity was assessed at baseline, and visits 3, 5, 6 via a modified Kaiser Permanente Health Plan Activity Survey(18), with values for visits 1, 4, and 7 carried forward from the last completed observation. Alcohol use was reported average weekly number of servings of beer, wine, liquor, or mixed drinks. Menopausal status was obtained from self-reported bleeding patterns over the year preceding the visit, categorized as premenopausal (bleeding in the previous three months with no change in cycle predictability in the past year) early perimenopausal (bleeding in the previous three months with decrease in cycle predictability in the past year), late perimenopausal (<12 and >3 months of amenorrhea), or postmenopausal (≥12 of amenorrhea) at each visit. Consistent with our prior work(5, 19), baseline depressive symptoms (assessed through the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale)(20) and anxiety symptoms (sum score of number of days in the past two weeks, 0=no days-4=every day, reporting irritability or grouchiness, feeling tense or nervous, heart pounding or racing, or feeling fearful for no reason) were considered as covariates due to their associations with vasomotor symptoms(1) and cardiovascular risk(21, 22). BMI was derived from annual physical measures. Cardiovascular disease status (reported hypertension, angina, stroke, or heart attack) and use of cardiovascular disease medications (reported use of medication for a heart condition, an anticoagulant, or for blood pressure lowering in the past year) were combined into a single variable and covaried. Hypertension was included with other cardiovascular disease variables to avoid model over-fitting given the large number of covariates in models. Reported lipid lowering medication use was covaried separately.

Data Analyses

Baseline differences between included/excluded participants were tested using Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Univariable analyses of relations between covariates and each outcome were performed at baseline using linear regression. Longitudinal associations between hot flashes/night sweats and each lipid marker were evaluated using linear mixed effects models to handle within-subject correlations and unequal measurement intervals/durations (e.g., missing visits)(23). Repeated measures of each outcome were modeled as a function of repeated measures of hot flashes or night sweats (considered in separate models) with a random intercept to account for random effects associated with the intercept for each participant. An auto-regressive covariance structure, which assumes that a woman’s observations more proximal in time will be more highly correlated than those more distal in time, was selected due to the longitudinal nature of the data and based upon the Akaike information criterion (AIC; lower indicating better model fit)(24). Models were adjusted for age and site, and next additionally for covariates selected based upon previously-documented associations with lipids and present associations with outcomes at p<0.05. Particular attention was paid to include factors that may act as confounders in these analyses (associated with both vasomotor symptoms and lipids; e.g., education, smoking, race/ethnicity, menopausal stage, BMI)(1, 25). Serum E2 was added to covariate-adjusted models along with blood draw timing (in vs. out of cycle day 2–5 window). FSH was also considered instead of E2 in secondary models. Since cycle day of blood draw and menopausal status were collinear (only early peri-and premenopausal women had menstrual cycles to provide timed sample), they were considered as a composite variable (pre- or perimenopausal timed sample, pre- or perimenopausal untimed sample, late perimenopausal, postmenopausal). For time-varying covariates, values concurrent with the outcome measure time point were used. Linear trends were tested by treating hot flashes or night sweats as a continuous variable (26). Interactions between hot flashes/night sweats and race/ethnicity, menopausal status, and BMI were examined as cross product terms in univariable and multivariable models. For presentation, interactions for BMI are displayed as predicted means for vasomotor symptoms level by obesity status (BMI<25, 30>=BMI>=25, BMI>30). Residual analysis and diagnostic plots (e.g., scatter plots, histograms) were conducted to verify model assumptions of normality. Analyses were performed with SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Models were 2-sided, α=0.05.

Results

The sample at baseline was on average 46 years old, overweight, and nonsmoking (Table 1). At baseline, approximately a third of the sample had vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes: 26%, night sweats: 29%), which increased over the study visits (e.g., at visit 7, hot flashes: 54%; night sweats: 38%), Consistent with other SWAN reports(25, 27), factors significantly (p<0.05) associated with a more adverse lipid profile at baseline included older age, Hispanic race/ethnicity (relative to non-Hispanic Caucasian), smoking, low education, not drinking alcohol, being early perimenopausal (vs. premenopausal), and having a high BMI, low physical activity, low E2, high FSH, and high anxious or depressive symptoms. Japanese and Chinese women had a more favorable lipid profile than non-Hispanic Caucasian women.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (n=3,201)

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 45.9 (2.7) |

| Race or ethnicity, n (%) | |

| African American | 883 (27.6) |

| Chinese | 247 (7.7) |

| Hispanic | 271 (8.5) |

| Japanese | 280 (8.7) |

| Caucasian | 1520 (47.5) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school or less | 780 (24.6) |

| Some college | 1011 (31.9) |

| College graduate or postgraduate degree | 1379 (43.5) |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |

| Premenopausal | 1686 (53.9) |

| Early perimenopausal | 1441 (46.1) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.2 (7.2) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 535 (16.9) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | |

| Fewer than one time per month | 1336 (52.4) |

| one or more time per month and fewer than two times per week | 695 (27.2) |

| two times per week or more | 521 (20.4) |

| Physical activity score, mean (SD) | 7.7 (1.8) |

| Cardiovascular disease status or medication use, n (%) | 649 (20.7) |

| Lipid lowering medication use, n (%) | 27 (0.9) |

| Frequency of hot flashes, n (%) | |

| None | 2351 (73.7) |

| 1–5 days | 604 (19.0) |

| 6 days or more | 233 (7.3) |

| Frequency of night sweats, n (%) | |

| None | 2263 (71.0) |

| 1–5 days | 719 (22.6) |

| 6 days or more | 205 (6.4) |

| Depressive symptom score, median (IQR)* | 8.0 (3.0-15.0) |

| Anxiety score, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) |

| E2, pg/ml, median (IQR) | 55.3 (33.1,88.7) |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone, mIU/ml, median (IQR) | 15.8 (10.8, 26.2) |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mg/dL, M (SD) | 115.9 (31.0) |

| High-density lipoprotein, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 56.0 (14.5) |

| ApolipoproteinA-1, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 149.7 (25.0) |

| ApolipoproteinB, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 111.1(29.4) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 90.0 (67.0, 130.0) |

| Lipoprotein(a) mg/dL, median (IQR) | 18.0 (6.0,43.0) |

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; E2, estradiol.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score.

In age and site-adjusted models, both hot flashes and night sweats, particularly when experienced frequently (≥6 days, past two weeks), were associated with higher LDL-C, HDL-C, apoB, apoA-1, triglycerides, and to a lesser extent higher Lp(a) over the 8-year study period (Table 2). For example, the age- and site- adjusted estimated means (in mg/dL) from the mixed models for hot flashes were 117.7 (none), 119.6 (1–5 days), and 120.5 (≥6 days) for LDL-C; 57.1 (no days), 57.5 (1–5 days), and 57.9 (≥6 days) for HDL-C; and 121.0 (none), 125.2 (1–5 days), and 131.3 (≥6 days) for triglycerides. In multivariable models, associations remained for all lipid markers except Lp(a) (Table 3). Associations remained with further adjustment for E2 (Table 4).

Table 2.

Age and Site-Adjusted Associations Between Vasomotor Symptoms and Lipids, Lipoproteins, and Apolioproteins in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, 1996–2004

| LDL-C | ApolipoproteinB | HDL-C | ApolipoproteinA-1 | Lipoprotein(a)* | Triglycerides* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Percent Change (95%CI) | Percent Change (95%CI) | |

| Hot flushes | ||||||

| None† | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1–5 days | 1.88 (0.47)|| | 1.61 (0.41)|| | 0.43 (0.17)§ | 1.50 (0.44)|| | 0.64 (−1.06, 2.35) | 3.26 (1.82, 4.72)|| |

| 6 or more days | 2.84 (0.61)|| | 2.91 (0.53)|| | 0.86 (0.23)|| | 3.14 (0.57)|| | 2.70 (0.46, 5.00)§ | 6.96 (5.04, 8.92)|| |

| P-value for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Night sweats | ||||||

| None† | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1–5 days | 1.03 (0.46)§ | 1.46 (0.41)|| | 0.34 (0.17)¶ | 1.69 (0.44)|| | −0.52 (−2.19, 1.19) | 2.38 (0.96, 3.82)# |

| 6 or more days | 1.73 (0.69)§ | 1.80 (0.61)# | 0.57 (0.26)§ | 2.66 (0.65)|| | −0.47 (−2.96, 2.09) | 7.09 (4.90, 9.33)|| |

| P-value for trend | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.60 | <0.001 |

LDL, low-density lipoprotein-C; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-C; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval.

Natural log transformed. Regression coefficients back transformed using (100*(exp(beta)−1) for percent change and 95%CI

Reference group

P<0.05

P<0.001

P<0.10

P<0.01

Table 3.

Multivariable-Adjusted Associations Between Vasomotor Symptoms and Lipids, Lipoproteins, and Apolioproteins in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, 1996–2004

| LDL-C | ApolipoproteinB | HDL-C | Apolipoprotein A-1 | Lipoprotein(a)* | Triglycerides* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Percent Change (95%CI) | Percent Change (95%CI) | |

| Hot flushes | ||||||

| None† | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1–5 days | 1.48 (0.47)‡ | 1.41 (0.41)§ | 0.30 (0.18) | 0.92 (0.47)|| | 0.10 (−1.71, 1.95) | 2.91 (1.41, 4.43)§ |

| 6 or more days | 2.13 (0.62)§ | 2.51 (0.54)§ | 0.77 (0.24)‡ | 1.97 (0.62)‡ | 1.93 (−0.52, 4.44) | 5.90 (3.86, 7.97)§ |

| P-value for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| Night sweats | ||||||

| None† | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1–5 days | 0.99 (0.46)# | 1.37 (0.41)§ | 0.35 (0.18)|| | 1.40 (0.47)‡ | −0.48 (−2.27, 1.35) | 2.36 (0.88, 3.86)‡ |

| 6 or more days | 1.14 (0.70) | 1.15 (0.62)|| | 0.77 (0.28)‡ | 2.52 (0.71)§ | −1.01 (−3.74, 1.79) | 6.32 (4.00, 8.69)§ |

| P-value for trend | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.40 | <0.001 |

LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-C; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-C; SE, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, site, race, education, menopausal status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, smoking status, anxiety, body mass index, cardiovascular disease status or medication use, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Natural log transformed. Regression coefficients back transformed using (100*(exp(beta)-1) for % change and 95%CI

Reference group

P<0.01

P<0.001

P<0.10

P<0.05

Table 4.

Multivariable, Estradiol-Adjusted Associations Between Vasomotor Symptoms and Lipids, Lipoproteins, and Apolioproteins in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, 1996–2004

| LDL-C | Apolioproteins B | HDL-C | Apolioproteins A-1 | Lipoprtein(a)* | Triglycerides* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Regression Coefficient (SE) | Percent Change (95%CI) | Percent Change (95%CI) | |

| Hot flushes | ||||||

| None† | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1–5 days | 1.11 (0.46)‡ | 1.09 (0.41)§ | 0.35 (0.18)|| | 1.10 (0.47)‡ | −0.17 (−1.98, 1.67) | 2.88 (1.38, 4.41)¶ |

| 6 or more days | 1.38 (0.62)‡ | 2.00 (0.54)¶ | 0.84 (0.24)¶ | 2.17 (0.62)¶ | 1.49 (−0.96, 4.00) | 5.62 (3.58, 7.70)¶ |

| P-value for trend | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Night sweats | ||||||

| None* | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1–5 days | 0.81 (0.46)|| | 1.23 (0.41)§ | 0.34 (0.18)|| | 1.46 (0.47)§ | −0.35 (−2.15, 1.49) | 2.41 (0.92, 3.92)§ |

| 6 or more days | 0.51 (0.70) | 0.78 (0.62) | 0.81 (0.28)§ | 2.63 (0.71)¶ | −1.31 (−4.03, 1.50) | 6.07 (3.75, 8.45)¶ |

| P-value for trend | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-C; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-C; SE, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, site, race, education, menopausal status and cycle day of blood draw, alcohol consumption, physical activity, smoking status, anxiety, body mass index, cardiovascular disease status or medication use, lipid-lowering medication use, and estradiol (log).

Natural log transformed. Regression coefficients back transformed using (100*(exp(beta)−1) for % change and 95%CI.

Reference group

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.10

p<0.001

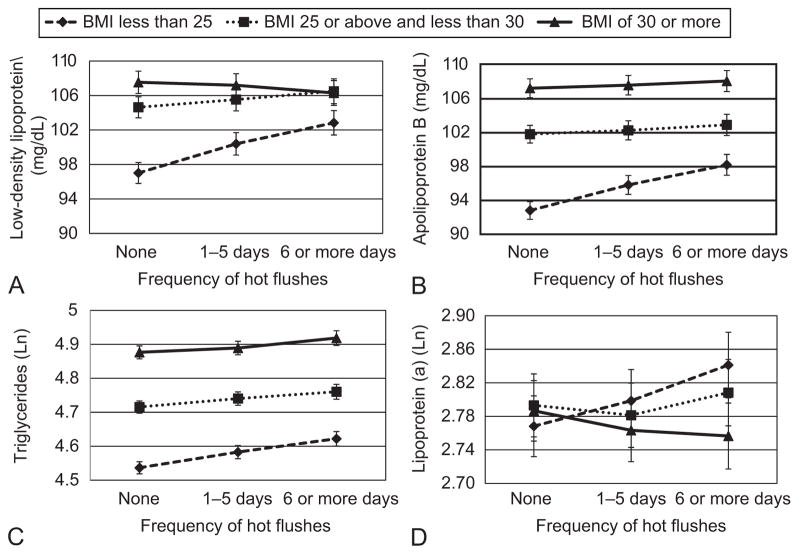

Additional analyses were conducted. First, given prior evidence of effect modification by BMI(7), we examined interactions between vasomotor symptoms and BMI for each outcome. Significant interactions between BMI and hot flashes for LDL-C, apoB, Lp(a) and triglycerides (p’s<0.05; Figure), and between BMI and night sweats for LDL and apoB (p’s<0.05) in multivariable models. Associations were strongest among leaner women (Figure 1). There were no interactions by menopausal stage nor by race/ethnicity, with the exception of one interaction (p<0.05) between hot flashes and race/ethnicity in relation to apoB (with associations strongest among Caucasian and Japanese women; data not shown), and thereby associations were broadly similar across racial/ethnic groups. Finally, FSH was substituted for E2 as a covariate in multivariable models. Findings were similar to models with E2, with significant associations between vasomotor symptoms for HDL-C [relative to no hot flashes, 1–5 days: β(SE)=0.24(0.18), p=0.18; 6+days: β(SE)=0.59(0.24), p=0.02], apoB [relative to no hot flashes, 1–5 days: β(SE)=0.96(0.41), p=0.02; 6+days: β(SE)=1.71(0.54), p=0.002], apoA-1 [relative to no hot flashes, 1–5 days: β(SE)=0.87(0.47), p=0.07; 6+days: β(SE)=1.66(0.63), p=0.008], and triglycerides [relative to no hot flashes, 1–5 days: %change (95%CI)=2.90(1.39, 4.42), p<0.001; 6+days: %change (95%CI)=5.70(3.65, 7.79), p<0.001], with the exception LDL-C [relative to no hot flashes, 1–5 days: β(SE)=0.82(0.46), p<0.10; 6+days: β(SE) 0.77(0.62), p=0.21], for which associations were somewhat reduced. Findings for night sweats were similar.

Figure 1.

Predicted means for low-density lipoprotein (LDL; A), apolipoproteinB (B), triglycerides (C), and lipoprotein (a) (D) by hot flashes and obesity status. Covariates: Age, study site, race, education, menopausal status, alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity, cardiovascular disease status/medication, lipid lowering medication, and (for low-density lipoprotein, apolipoproteinB, triglycerides) anxiety or (for lipoprotein (a)) depressive symptoms. Interaction between body mass index (BMI) and low-density lipoprotein: P<.001; interaction between BMI and apolipoprotein B: P<.001; interaction between BMI and triglycerides: P=.01; interaction between BMI and lipoprotein (a): P<.001.

Discussion

In this large, community-based, multi-ethnic study, vasomotor symptoms, particularly frequent vasomotor symptoms, were associated with elevated LDL-C, HDL-C, apoB, apoA-1, and triglycerides over an eight-year period encompassing the menopausal transition. Associations between vasomotor symptoms and lipid markers persisted controlling confounders, and were not explained by differences in E2 or, in most cases, FSH. Associations were broadly similar across ethnic groups, and were most pronounced among leaner women. Thus, these data provide the most definitive data to date linking vasomotor symptoms to elevated lipids among women transitioning through the menopause.

Our results indicate that vasomotor symptoms are associated with higher triglycerides, LDL-C, and apoB. These associations are broadly consistent with other large community-based cross sectional studies(9). These markers are well known to be associated with elevated cardiovascular risk(28). Thus, positive relations between vasomotor symptoms and triglycerides, LDL-C, and apoB are consistent with the findings of elevated cardiovascular risk among women with frequent or severe vasomotor symptoms and may be one mechanism linking these symptoms to cardiovascular risk.

However, we unexpectedly observed significant positive associations between vasomotor symptoms and HDL-C and its protein component apoA-1, generally considered cardioprotective(28). The reason for this pattern is not immediately clear, and a chance finding cannot be ruled out. However, it is notable that data from SWAN(29) and other studies(30) indicate that HDL may not universally be cardioprotective, potentially varying by menopausal stage. Whereas higher HDL-C is associated with lower subclinical cardiovascular disease during the pre- and early perimenopause, it may become pro-atherogenic during the late perimenopause and early postmenopause, when vasomotor symptoms peak(29). These changes may be due in part to HDL particle size reductions that may occur as women transition through the menopause(29) and evidence that larger, but not smaller HDL particles associated with cardioprotection(31). Thus, although speculative, changes in the atherogenic potential of HDL as women transition through the menopause and symptoms peak may play a role in the positive associations between HDL-C/apoA-1 and vasomotor symptoms observed here.

Interactions were observed by BMI, with findings most pronounced among the leaner women. Obesity is generally strongly associated with an adverse lipid profile. Thus, it is possible that the effect of BMI on lipids or vasomotor symptoms among heavier women overwhelmed the more modest associations between vasomotor symptoms and lipid markers observed here. Notably, the association between menopausal status and lipids in SWAN was also stronger among leaner women, potentially for similar reasons as observed here(25, 27).

Our findings of increased LDL-C, apoB, and triglycerides are broadly consistent with the two other population-based studies. In one large cross sectional study, vasomotor symptoms were associated with elevated total cholesterol(8). In a second cross sectional analysis, “sweats” (although not hot flashes) were associated with elevated total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides(9). Smaller clinical studies tend to show more mixed results. A small study of 32 healthy women found that hot flashes were associated with lower HDL-C and apoA-1, but not LDL-C nor apoB(11). Another study (n=150) of very healthy women found no associations between hot flashes and lipids(10), although very few women (n=23) without vasomotor symptoms were assessed. The reasons for differences between studies are not immediately apparent but may be due to differences in sample size and selection of women to be low on cardiovascular risk factors yet highly symptomatic. None of these studies examined differences by obesity status.

The physiology linking vasomotor symptoms to lipids is not entirely clear. Women with cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and smoking tend to have more vasomotor symptoms(1). However, controlling for these factors did not eliminate the observed associations. The menopausal transition, including the changing hormonal milieu, is clearly associated with elevated vasomotor symptoms as well as changes in lipids, particularly LDL-C(27). However, controlling for menopausal stage and E2 did not sizably reduce associations, and controlling for FSH reduced associations only between vasomotor symptoms and LDL-C. Thus, these hormones explained only a small part of the associations observed here. Several other systems may be relevant. There is indication of poorer endothelial function(5, 6) and a more adverse hemostatic profile(19) among women with vasomotor symptoms. Further, we and others found changes in autonomic nervous system balance favoring increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic tone with vasomotor symptoms(32), a profile associated with cardiovascular risk. Finally, others have proposed changes in hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis function with vasomotor symptoms(33). Thus, many mechanisms may link vasomotor symptoms to altered lipid profiles.

In this study, while associations were observed for both infrequent (1–5 days in the past two weeks) and frequent (6 or more days in the past two weeks) vasomotor symptoms, associations were most pronounced for frequent vasomotor symptoms. Notably, some (but not all)(5) prior work has shown that it is the more frequent(7) or moderate-severe(3, 4) vasomotor symptoms that are associated with elevated cardiovascular risk, suggesting that higher levels of symptomatology are most relevant. Moreover, although associations were apparent for hot flashes and night sweats, associations for hot flashes were somewhat more robust to adjustment. We have previously found stronger associations with indices of cardiovascular risk for hot flashes versus night sweats(5, 7, 19), potentially due to a differing underlying physiology between the two or to a lower reliability of reporting night sweats given their occurrence during sleep.

The study results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, as this was a large, epidemiologic investigation, and the measures of vasomotor symptoms were relatively crude, asking women to recall the frequency of symptoms over two weeks. These measures are clearly querying about menopausal vasomotor symptoms, and thereby are an improvement over other epidemiologic work in this area(9). However, there were likely some error introduced by memory in these reports, and these measures did not allow us to examine measures such as a more detailed symptom frequency or severity. Moreover, hormonal measures were assessed yearly, and some women likely had widely fluctuating hormone concentrations. Thus, exposure to these hormones may not have been fully quantified, and further investigation of them in these associations is merited. Further, although a range of medical conditions and medications were controlled, some women may have had other medical conditions or medication use that could have impacted the markers assessed here. It is also important to note that the magnitude of the differences in lipids by level of symptoms, while statistically significant, was not large. Finally, although this was a longitudinal investigation, the directionality or causal nature of these associations cannot be inferred.

This study had several strengths. This study is the first to examine longitudinal associations between vasomotor symptoms and lipid markers. It investigated a large, longitudinal, community-based investigation of women transitioning through the menopause. It included eight years of follow up, a design that stands in contrast to the exclusively cross-sectional research on this topic. It examined associations between vasomotor symptoms and lipids in a sample that included women from several different ethnic groups. Thus, it provides the richest analysis on this topic to date.

In conclusion, VMS were associated with elevated LDL-C, HDL-C, apoB, apoA-1, and triglycerides in this community-based sample of women transitioning through the menopause. These associations could not be fully explained by shared risk factors, E2, or FSH as assessed here. They were strongest among lean women. These findings may contribute to ongoing efforts to better understand the physiology of vasomotor symptoms as well as any implications vasomotor symptoms may have for cardiovascular health.

Acknowledgments

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants NR004061; AG012505, AG012535, AG012531, AG012539, AG012546, AG012553, AG012554, AG012495). This work was also supported by NIH grant AG029216 (Thurston).

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

The authors thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor - Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 - present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994-2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA - Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 - present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 - 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL - Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 - present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 - 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser - Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles - Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY - Carol Derby, PI 2011 - present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010 - 2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 - 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry - New Jersey Medical School, Newark - Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 - 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA - Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD - Sherry Sherman 1994 - present; Marcia Ory 1994 - 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD - Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor - Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA - Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 - present; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 - 2001. Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Joffe has received research support from Bayer Health Care Pharmaceuticals, and has performed advisory or consulting work for Sanofi-Aventis/Sunovion, Pfizer, and Noven. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gold E, Colvin A, Avis N, Bromberger J, Greendale G, Powell L, et al. Longitudinal analysis of vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Am J Public Health. 2006 Jul;96(7):1226–35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szmuilowicz ED, Manson JE, Rossouw JE, Howard BV, Margolis KL, Greep NC, et al. Vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2011 Jun;18(6):603–10. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182014849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Wu L, Barad D, Barnabei VM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007 Apr 4;297(13):1465–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang AJ, Sawaya GF, Vittinghoff E, Lin F, Grady D. Hot flushes, coronary heart disease, and hormone therapy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2009 Jul-Aug;16(4):639–43. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31819c11e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thurston RC, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Everson-Rose SA, Hess R, Matthews KA. Hot flashes and subclinical cardiovascular disease: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Heart Study. Circulation. 2008 Sep 16;118(12):1234–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bechlioulis A, Kalantaridou SN, Naka KK, Chatzikyriakidou A, Calis KA, Makrigiannakis A, et al. Endothelial function, but not carotid intima-media thickness, is affected early in menopause and is associated with severity of hot flushes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Mar;95(3):1199–206. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thurston RC, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Everson-Rose S, Hess R, Powell L, Matthews K. Hot flashes and carotid intima media thickness among midlife women. Menopause. 2011 Apr;18(4):352–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181fa27fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gast GC, Grobbee DE, Pop VJ, Keyzer JJ, Wijnands-van Gent CJ, Samsioe GN, et al. Menopausal complaints are associated with cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension. 2008 Jun;51( 6):1492–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.106526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gast GC, Samsioe GN, Grobbee DE, Nilsson PM, van der Schouw YT. Vasomotor symptoms, estradiol levels and cardiovascular risk profile in women. Maturitas. 2010 Jul;66(3):285–90. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuomikoski P, Mikkola TS, Hamalainen E, Tikkanen MJ, Turpeinen U, Ylikorkala O. Biochemical markers for cardiovascular disease in recently postmenopausal women with or without hot flashes. Menopause. 2010 Jan-Feb;17(1):145–51. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181acefd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sassarini J, Fox H, Ferrell W, Sattar N, Lumsden MA. Vascular function and cardiovascular risk factors in women with severe flushing. Clinical endocrinology. 2011 Jan;74(1):97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowers M, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, Morganstein D, Gold EB, Greendale GA, et al. SWAN: A multicenter, multiethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, Lobo AR, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathology. New York: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 175–88. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner P, Freidel J, Bremner W, Stein E. Standardization of micro-methods for plasma cholesterol, triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol with the Lipid Research Clinics’ methodology. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1981;19(8):850. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warnick G, Albers J. A comprehensive evaluation of the heparin-manganese precipitation procedure for estimating high density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Lipid Res Nurs Health. 1978;19(1):65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedewald W, Levy R, Fredrickson D. Estimation of the concentration of low density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers G, Cooper G, Winn C, Smith S. The Centers for Disease Control–National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Lipid Standardization Program: an approach to accurate and precise lipid measurements. Clin Lab Med. 1989;9(1):105–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.England BG, Parsons GH, Possley RM, McConnell DS, Midgley AR. Ultrasensitive semiautomated chemiluminescent immunoassay for estradiol. Clin Chem. 2002 Sep;48(9):1584–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ainsworth BE, Sternfeld B, Richardson MT, Jackson K. Evaluation of the kaiser physical activity survey in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000 Jul;32(7):1327–38. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurston R, El Khoudary S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Crandall C, Gold E, Sternfeld B, et al. Are vasomotor symptoms associated with alterations in hemostatic and inflammatory markers? Findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Menopause. 2011 Oct;18(10):1044–51. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821f5d39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I, Weiss ST, Sparrow D. Anxiety and coronary heart disease: a synthesis of epidemiological, psychological, and experimental evidence. Ann Behav Med. 1998 Spring;20(2):47–58. doi: 10.1007/BF02884448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Strauman T, Robins C, et al. Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004 May-Jun;66(3):305–15. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126207.43307.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19(6):716– 23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derby CA, Crawford SL, Pasternak RC, Sowers M, Sternfeld B, Matthews KA. Lipid changes during the menopause transition in relation to age and weight: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009 Jun 1;169(11):1352–61. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodward M. Epidemiology: Study design and data analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews KA, Crawford SL, Chae CU, Everson-Rose SA, Sowers MF, Sternfeld B, et al. Are changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors in midlife women due to chronological aging or to the menopausal transition? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009 Dec 15;54(25):2366–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women--2011 update: a guideline from the american heart association. Circulation. 2011 Mar 22;123(11):1243–62. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodard GA, Brooks MM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Mackey RH, Matthews KA, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Lipids, menopause, and early atherosclerosis in Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Heart women. Menopause. 2010 Nov 19; doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181f6480e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan A, Dwyer J. Sex differences in the relation of HDL cholesterol to progression of carotid intima-media thickness: the Los Angeles Atherosclerosis Study. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:e191–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asztalos BF, Collins D, Cupples LA, Demissie S, Horvath KV, Bloomfield HE, et al. Value of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) subpopulations in predicting recurrent cardiovascular events in the Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2005 Oct;25(10):2185–91. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000183727.90611.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thurston R, Christie I, Matthews K. Hot flashes and cardiac vagal control: A link to cardiovascular risk? Menopause. 2010 May-Jun;17(3):456–61. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c7dea7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woods NF, Mitchell ES, Smith-Dijulio K. Cortisol levels during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2009 Jul-Aug;16(4):708–18. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318198d6b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]