Abstract

Glypican-3 (GPC3) is highly expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and a growing body of evidence supports the role of GPC3 in HCC pathogenesis. In this review, we discuss recent developments regarding the regulation of GPC3 in HCC and provide insight about GPC3 as a potential therapeutic target in liver cancer. One of the most well studied pathways related to the biological functions of GPC3 is the Wnt signaling pathway. GPC3 may form a complex with Wnt and stimulates HCC growth. GPC3 does this by facilitating and/or stabilizing the interaction between Wnt and Frizzled, leading to the activation of downstream signaling pathways. This signaling complex is also affected by Sulfatase 2 (SULF2), a heparin-degrading endosulfatase. Removing the sulfate groups from GPC3 enhances Wnt signaling and HCC proliferation suggesting that GPC3, Wnts and SULF2 may be part of “a glypican-Wnt/growth factor complex”, which may determine cell growth, differentiation and migration. Given the high expression of GPC3 in HCC, GPC3 has been suggested as a potential target for antibody-based therapy for liver cancer. A monoclonal antibody (GC33) is being evaluated in clinical studies as a single agent or in combination with Sorafenib to treat patients with advanced or metastatic HCC. Ongoing clinical trials will help define the utility of GPC3 as a novel target for liver cancer therapy.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, glypican-3, Wnt signaling, heparan sulfate glycan, Sulfatase, Sulf1 and Sulf2

1. INTRODUCTION

Glypicans are a family of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) associated with the cell-surface through a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchorage. Loss of function mutations of GPC3 leads to Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome (SGBS), a rare X-linked disorder with significant overgrowth [1], which has also been observed in GPC3-null mice [2]. GPC3 is expressed ubiquitously in the embryo but is reduced in the central nervous system (CNS) in adults [3]. The overexpression of GPC3 has been detected in a number of human malignancies, including HCC, melanoma and ovarian clear-cell carcinoma. HCC accounts for about 75% of liver cancer cases. Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is the second most common primary liver malignant tumor arising from cholangiocytes and CCA accounts for about 10% of primary liver cancer cases. GPC3 is highly expressed in at least 70% of HCC [4, 5], which is not seen CCA [6]. The expression of GPC3 is correlated with poorer prognosis in patients diagnosed with HCC [7] and emerging evidence suggests that GPC3 is a potential biomarker for HCC.

2. THE STRUCTURE OF GPC3

All glypicans are of a similar size and share 14 conserved cysteine residues, indicating that they have a common characteristic structure. The GPC3 gene localizes to the × chromosome and encodes a 70-kDa precursor protein that is cleaved by Furin to generate a 40-kDa N- terminal and a 30-kDa C-terminal fragment. The C terminus of GPC3 links to the membrane through the GPI anchor and is post-translationally modified with two O-linked heparan sulfate (HS) side chains close to the cell surface [6, 8]. The three-dimensional structure of GPC3, or any other glypicans, has not been solved. Based on its primary amino acid sequence, GPC3 has three functional domains: the N terminus, the C terminus protein and two HS glycan chains. The N-terminal and C-terminal proteins form the core protein of GPC3.

The GPC3 gene encodes the core protein with a molecular mass of approximately 70 kDa. In addition to the most common isoform of GPC3, three variants have been identified. However, the distribution and functional significance of various GPC3 isoforms are unknown [6]. GPC3 may be cleaved by Furin between Arg358 and Ser359, generating to two subunits: a 40 kDa N-terminal subunit and a 30 kDa C-terminal subunit. Cleavage is required for GPC3 to modulate cell survival and Wnt signaling in zebrafish [9], but is not required for HCC cell growth [10]. The two subunits may still be linked to each other after cleavage through disulfide bond formation between the conserved cysteine residues, or by insufficient cleavage. For example, western blot analysis of HCC cells shows the presence of full-length GPC3 proteins, indicating that cleavage is blocked or insufficient. [11]. Further studies are necessary to characterize GPC3 in HCC and other GPC3-expressing tumors to determine the efficiency of furin cleavage.

The HS chains on GPC3 are functionally important glycosaminoglycans. They are negatively-charged. This feature enables HS to bind positively-charged growth factors [12], including HGFs, FGFs, Wnts, Hedgehog and bone morphogenetic proteins [8]. Therefore, the HS chains may act as “docking sites” for these growth factors. However, the function of the HS chain may also depend on cellular context. For example, the HS chains of GPC3 are required for the binding of Wnt5A to MCF-7 breast cancer cells and Wnt signaling activation in CHO cells [9]. In contrast, neither the HS chains nor processing by furin-like convertases is essential for the interaction of GPC3 and Wnt in HCC cells [10, 13]. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out potentially important functions of the HS chains in HCC. Although Wnt is able to bind to both GPC3 and its mutant form lacking the HS chains (GPC3ΔGAG), GPC3ΔGAG stable lines show a significant decrease in cell proliferation and β-catenin transcriptional activity [13]. This has only been shown in PLC-PRF-5 cells and further studies with other HCC cell lines are necessary.

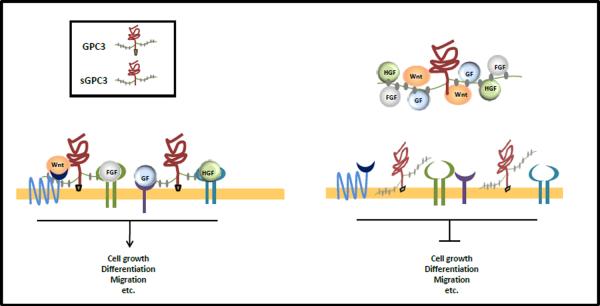

Based on the primary amino acid sequence of GPC3, we predicted that serine 560 may serve as a cleavage site in GPC3 for GPI anchorage [6]. The cell surface localization of GPC3 is required for cell growth and Wnt activation in HCC [13]. Interestingly, secreted GPC3 was detected in the sera from approximately 50% of HCC patients [14–17], although it is not clear what form is present in the circulating blood of cancer patients. Glypicans may be shed from tumor cells into the extracellular environment via cleavage of the GPI anchor by the extracellular lipase, Notum [18, 19]. Recently, Filmus and colleagues constructed a mutant version of GPC3 in lentivirus, lacking the GPI anchoring domain. HCC cell lines expressing the mutant form showed a lower proliferation rate in vitro as well as in vivo. We have shown that a recombinant form of GPC3, lacking the GPI linkage and therefore soluble, inhibited the growth of GPC3-expressing HCC in vitro [20] [11]. These studies indicate that soluble GPC3ΔGPI can act as a dominant negative form of GPC3 to inhibit cell growth, possibly by competing with endogenous GPC3 for binding to Wnts and other growth factors. The binding may require both the core protein and the HS chains, although further studies are needed to confirm this (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

A working model of how soluble GPC3ΔGPI (sGPC3) proteins inhibit HCC cell growth. Soluble GPC3ΔGPI proteins may function as a dominant-negative form to inhibit the interactions between cell surface endogenous GPC3, Wnt, growth factors or ligands by sequestering these soluble factors away from the cell surface.

3. THE REGULATION OF GPC3 IN HCC

Many studies indicate that GPC3 is involved in cell growth regulation [13, 21, 22]. However, depending on different cellular environments, GPC3 may either promote or inhibit cell growth. GPC3 binds Wnt [13], Hedgehog [23] and Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) [24]. Although cytoplasmic GPC3 has been observed in a high percentage of HCC tissues by immunohistochemistry, its biological function is unknown [7]. Studies have shown that GPC3 promotes the proliferation of HCC cells by complexing with Wnt and enhancing activation of the canonical signaling pathway [13, 25]. Consistent with this, GPC3-knockout mice exhibit alternations in Wnt signaling. Compared with wild-type mice, GPC3-knockout mice show an increase in cytoplasmic β-catenin expression levels, which lead to higher expression levels of cyclin D1 [26].

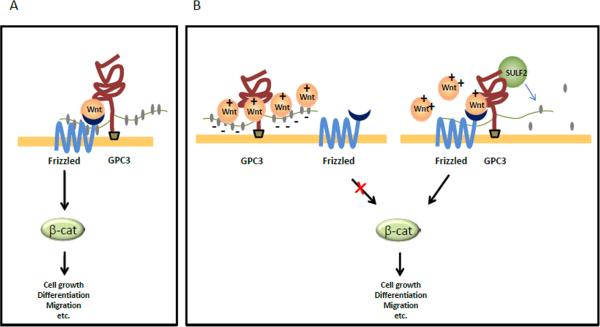

Capurro et al. (2005) showed that GPC3 stimulates HCC cell growth in vitro and in vivo by increasing autocrine or paracrine canonical Wnt signaling [13]. Furthermore, overexpression of GPC3 promotes the proliferation and growth of PLC-PRF-5 cells transplanted into xenograft mice. GPC3 increases β-catenin stabilization, in response to exogenous canonical Wnts and cell binding of Wnt3a. Co-immunoprecipitation studies in HEK-293 cells expressing GPC3 and Wnt revealed that the two proteins were able to form a complex. A mutant GPC3 lacking the HS side chains (GPC3ΔGAG) also showed a similar interaction with Wnt, indicating that the GPC3-Wnt complex is mediated through the core GPC3 protein and that the HS sulfate chain was not essential for activation of the Wnt pathway [13]. Lai et al. (2010) confirmed the endogenous interaction between GPC3 and Wnt in the HCC cell line Hep3B by co-immunoprecipitation assays. In addition, SULF2, an enzyme with 6-O-desulfatase activity in mammalian cells, formed a complex with GPC3 and Wnt [27]. This indicates that sulfation of HS may play an essential role in regulating Wnt activation. For example, Dhoot et al. (2001) demonstrated how QSulf1, an avian heparan-specific N-acetyl glucosamine sulfatase, regulated Wnt signaling through desulfation of cell surface HSPGs in C2C12 cells [28]. QSulf1-6-O desulfation of Glypican-1 reduced Wnt binding to heparin and HS chains. Additionally, Wnt-dependent Frizzled receptor activation is defective in HS biosynthesis deficient in CHO cells [29]. Interestingly, SULF2 is overexpressed in 60% of HCC and stimulates HCC cell growth and induces GPC3 expression in vitro and in vivo. Induced GPC3 also mediates the binding of FGF2 to cells [30], and stimulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, enhancing the oncogenic function of SULF2. Furthermore, increased expression of GPC3, Wnt3a and β-catenin are observed in HCC cell lines and nude mouse xenografts established from SULF2-transfected Hep3B cells [27]. Collectively, these results highlight the critical role of the Wnt signaling pathway in GPC3-mediated cell growth. These data also suggest that GPC3 and a variety of growth factors may form a complex.

One major question remains whether the interaction between GPC3 and such growth factors is mediated by the core protein or the HS chains. It has been reported that heparin can inhibit Wnt signaling [28], possibly by competing with Wnt for HS [12, 31]. In addition, HS chains also mediate the binding of other growth factors such as FGF2 and either heparin or heparitinase can inhibit the interaction between FGF2 and GPC3 [24]. The above evidence suggests that HS chains may function as storage sites for Wnt and other growth factors. It is also possible that GPC3, Wnt and SULF2 may be part of “a glypican-Wnt/growth factor complex”. Desulfation of GPC3 by SULF2 could release stored Wnt, increasing the local concentration, activating Frizzled receptors and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Fig.2). Little is known about how the interaction between Wnt and their receptors are regulated by GPC3. More studies are needed to dissect the biochemistry of the “glypican-Wnt/growth factor complex”.

Figure 2.

The glypican-Wnt/growth factor complex. A. The core protein of GPC3 facilitates or stabilizes the interaction between Wnt and Frizzled, thereby activating downstream signaling to stimulate HCC cell growth. B. The heparan sulfate (HS) chains of GPC3 may be used as storage sites for Wnt. SULF2-mediated desulfation of GPC3 releases stored Wnt and initiate binding to the Frizzled receptor, thus leading to Wnt signaling activation and HCC cell growth.

4. GPC3-TARGETED ANTIBODY THERAPY FOR HCC

Liver cancer is the fifth most common malignant cancer and is among the most deadly cancers in the world due to its late detection and poor prognosis. According to the American Cancer Society (www.cancer.org), 24,120 new cases of liver cancer were found and 18,910 patients died in the United States in 2010. HCC is often associated with liver disease, curtailing chemotherapy as a treatment option. While surgical resection offers a standard method for treatment of the disease, only a small portion of HCC patients are eligible for the procedure. As a result, there is an urgent need for new treatments that can be successfully applied to a large population of HCC patients. Given the high expression of GPC3 in HCC, GPC3 has been suggested as a potential candidate for novel cancer immunotherapy. GC33, a monoclonal antibody specific for human GPC3 from hybridoma, is being evaluated in Phase I clinical trials. In mice, the antibody has been shown to induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and also inhibits tumor growth inhibition of HepG2 and HuH-7 cell line xenografts [32, 33]. Macrophages may also play an important role in the anti-tumor activity of anti-GPC3 through a mechanism that is not dependent on ADCC [34–36]. To reduce immunogenicity in humans, humanized GC33 (hGC33) has been generated by complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) grafting and shows similar inhibition as GC33 against the HepG2 xenograft [32, 37]. hGC33 is being evaluated as a single agent or in combination with Sorafenib in the treatment of advanced or metastatic HCC in Phase I clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT00746317 and NCT00976170). Future development of monoclonal antibodies that target different functional domains of GPC3 may be particularly useful.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Although GPC3 has been suggested as a potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for liver cancer, the role of GPC3 in the pathogenesis of HCC remains poorly understood. Future studies are needed to reveal the functional domains of GPC3 that contribute to various extracellular and intracellular signaling pathways. While Wnt signaling has been a major focus on understanding the role of GPC3 in HCC, further studies are needed to explore molecular mechanisms beyond Wnt signaling. Serum GPC3 may prove to be a valuable tumor marker for patients with HCC. However, the biochemistry of serum GPC3 remains unclear. Given the high expression of GPC3 in HCC, GPC3 has been suggested as a potential target for novel antibody-based therapy for liver cancer. A humanized monoclonal antibody targeting GPC3 is currently being evaluated in clinical trials as a single agent or in combination with Sorafenib to treat advanced or metastatic HCC. The clinical trials will help define the utility of GPC3 as a novel target for antibody therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. Dr. Mitchell Ho is a co-inventor on patents assigned to the United States of America, as represented by the Department of Health and Human Services, for investigational products. We thank Jinping Lai (NCI, NIH) for critical reading of the manuscript, the NIH Fellows Editorial Board and Yen Phung (NCI, NIH) for editorial assistance. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The authors have no conflict of interest directly relevant to the content of this review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pilia G, et al. Mutations in GPC3, a glypican gene, cause the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel overgrowth syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;12(3):241–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cano-Gauci DF, et al. Glypican-3-deficient mice exhibit developmental overgrowth and some of the abnormalities typical of Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. J Cell Biol. 1999;146(1):255–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fransson LA. Glypicans. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35(2):125–9. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu HC, Cheng W, Lai PL. Cloning and expression of a developmentally regulated transcript MXR7 in hepatocellular carcinoma: biological significance and temporospatial distribution. Cancer Res. 1997;57(22):5179–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakatsura T, et al. Glypican-3, overexpressed specifically in human hepatocellular carcinoma, is a novel tumor marker. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00908-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho M, Kim H. Glypican-3: a new target for cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(3):333–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shirakawa H, et al. Glypican-3 expression is correlated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(8):1403–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filmus J, Capurro M, Rast J. Glypicans. Genome Biol. 2008;9(5):224. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Cat B, et al. Processing by proprotein convertases is required for glypican-3 modulation of cell survival, Wnt signaling, and gastrulation movements. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(3):625–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capurro MI, et al. Processing by convertases is not required for glypican-3-induced stimulation of hepatocellular carcinoma growth. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(50):41201–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng M, et al. Recombinant soluble glypican 3 protein inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(9):2246–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell AK, et al. Interactions of heparin/heparan sulfate with proteins: appraisal of structural factors and experimental approaches. Glycobiology. 2004;14(4):17R–30R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capurro MI, et al. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6245–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capurro M, et al. Glypican-3: a novel serum and histochemical marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hippo Y, et al. Identification of soluble NH2-terminal fragment of glypican-3 as a serological marker for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64(7):2418–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tangkijvanich P, et al. Diagnostic role of serum glypican-3 in differentiating hepatocellular carcinoma from non-malignant chronic liver disease and other liver cancers. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(1):129–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capurro M, Filmus J. Glypican-3 as a serum marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65(1):372. author reply 372-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreuger J, et al. Opposing activities of Dally-like glypican at high and low levels of Wingless morphogen activity. Dev Cell. 2004;7(4):503–12. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traister A, Shi W, Filmus J. Mammalian Notum induces the release of glypicans and other GPI-anchored proteins from the cell surface. Biochem J. 2008;410:503–511. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zittermann SI, et al. Soluble glypican 3 inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 126(6):1291–301. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Midorikawa Y, et al. Glypican-3, overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma, modulates FGF2 and BMP-7 signaling. Int J Cancer. 2003;103(4):455–65. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez AD, et al. OCI-5/GPC3, a glypican encoded by a gene that is mutated in the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel overgrowth syndrome, induces apoptosis in a cell line-specific manner. J Cell Biol. 1998;141(6):1407–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capurro MI, et al. Glypican-3 inhibits Hedgehog signaling during development by competing with patched for Hedgehog binding. Dev Cell. 2008;14(5):700–11. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song HH, Shi W, Filmus J. OCI-5/rat glypican-3 binds to fibroblast growth factor-2 but not to insulin-like growth factor-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(12):7574–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang JS, et al. Diverse cellular transformation capability of overexpressed genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315(4):950–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song HH, et al. The loss of glypican-3 induces alterations in Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(3):2116–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai JP, et al. The oncogenic effect of sulfatase 2 in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated in part by glypican 3-dependent Wnt activation. Hepatology. 2010;52(5):1680–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.23848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhoot GK, et al. Regulation of Wnt signaling and embryo patterning by an extracellular sulfatase. Science. 2001;293(5535):1663–6. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5535.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ai X, et al. QSulf1 remodels the 6-O sulfation states of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to promote Wnt signaling. J Cell Biol. 2003;162(2):341–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai JP, et al. Sulfatase 2 up-regulates glypican 3, promotes fibroblast growth factor signaling, and decreases survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47(4):1211–22. doi: 10.1002/hep.22202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cumberledge S, Reichsman F. Glycosaminoglycans and WNTs: just a spoonful of sugar helps the signal go down. Trends Genet. 1997;13(11):421–3. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishiguro T, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibody as a potential antitumor agent for human liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(23):9832–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakano K, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibodies cause ADCC against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378(2):279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takai H, et al. Involvement of glypican-3 in the recruitment of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8(24):2329–38. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.24.9985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takai H, et al. The expression profile of glypican-3 and its relation to macrophage population in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2009;29(7):1056–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takai H, et al. Histopathological analyses of the antitumor activity of anti-glypican-3 antibody (GC33) in human liver cancer xenograft models: The contribution of macrophages. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8(10):930–8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.10.8149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakano K, et al. Generation of a humanized anti-glypican 3 antibody by CDR grafting and stability optimization. Anticancer Drugs. 21(10):907–16. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833f5d68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]