Abstract

Transnational Organisations increasingly prioritise the need to support local research capacity in low and middle income countries in order that local priorities are addressed with due consideration of contextual issues. There remains limited evidence on the best way in which this should be done or the ways in which external agencies can support this process.

We present an analysis of the learning from the INDOX Research Network, established in 2005 as a partnership between the Institute of Cancer Medicine at the University of Oxford and India's top nine comprehensive cancer centres. INDOX aims to enable Indian centres to conduct clinical research to the highest international standards; to ensure that trials are developed to address the specific needs of Indian patients by involving Indian investigators from the outset; and to provide the training to enable them to design and conduct their own studies. We report on the implementation, outputs and challenges of simultaneously trying to build capacity and deliver meaningful research output.

Keywords: research capacity, research networks, research capacity building, India, cancer, NCD

Cancer is now the second leading cause of death in low- and middle-income countries and by 2030 it is estimated that 70% of all cancer cases will be in developing countries with potentially devastating consequences, both in terms of death and suffering as well as the huge financial costs which could overwhelm healthcare budgets (1). India, with a population of over one billion and an overstretched public health system is particularly vulnerable to this epidemic and its consequences. Although life expectancy in India has doubled since independence, it still has the largest disease burden of any country (2) and is experiencing rapid demographic, socioeconomic and risk-factor changes, particularly in urban areas, leading to an alarming rise in the incidence of cancer and other Non-communicable diseases (3–5).

Cancer is already the second leading cause of death in India and the incidence is expected to double in the next 10 years to 2 million cases a year (1, 4). Patients also usually have to cover the costs of treatment from their own pockets leading to increased poverty and even medical bankruptcies (5).

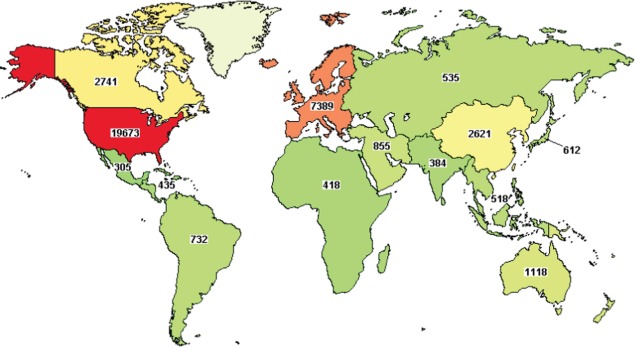

However, the ability to tackle this epidemic has been severely hampered by the lack of infrastructure and experience in clinical research (6, 7). Despite WHO's declaration in 2004 that: ‘Well planned health research is fundamental to the improvement of health in all countries’ (8), the reality remains that the vast majority of clinical research continues to be designed and conducted on the small minority of the world's population living in high-income countries (See Fig. 1) (9, 10). Specifically, of 32,346 studies currently being conducted in cancer, only 365 (∼1%) are in India despite it having 17% of the world's population and 10% of the global cancer burden (9). The evidence base (both for the effectiveness of treatments and the importance of risk factors) as well as the capacity to conduct research in all LMICs, including India, is grossly inadequate (11, 12).

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of clinical research studies in cancer (10).

The results of trials conducted under optimal conditions in high-income countries may not always be applicable to populations in LMICs and could precipitate a massive upsurge in the prescribing of costly drugs with limited clinical utility and in healthcare systems which are already financially overstretched. Furthermore, aside from the possible differential efficacy of therapeutic regimens between healthcare systems, patient safety may also be compromised. This risk is particularly prominent in therapeutic trials of cancer chemotherapy and novel biologic therapies, which can have potentially life-threatening side effects. To transport current best practice from the oncology clinics of high-income countries and use them in less developed healthcare systems may not only lack efficacy but could ultimately cost lives. Inequalities in healthcare can be further perpetuated by incentives for pharmaceutical companies to develop therapies for affluent, largely White populations from richer nations. With personalised medicine becoming a reality in oncology, we risk relegating the ethnicities concentrated in developing countries to an even lower standard of care (14). This potential ethnic prejudice can only be addressed by ensuring that clinical research is conducted in all populations.

Clinical trials in India

Although the number of clinical trials conducted in India has increased rapidly over the last 10 years, the vast majority of these had been commissioned and designed outside of India with little or no input from local investigators and are not designed to answer research questions of primary relevance to local populations, using India simply as a place to recruit extra patients (13, 14). Clearly, in order for research to have maximal benefits to the local population, it is essential that local investigators are involved in the design and conduct of these studies. For example, cancer of the gall bladder is one of the most common cancers in women in India with a very poor prognosis but relatively understudied by virtue of its concentration in low-income countries (15).

Indian centres had very limited experience in conducting clinical trials prior to 2005 and although the Principle Investigators (PIs) had some experience, training of more junior staff as well as research nurses and trial pharmacists had been far more limited. Building longer term capacity and sustainability was also a major problem as funding was provided by the sponsor only for the duration of the study and the trial co-ordinator, once trained, would then move on to another job.

In this article, we outline our experience in building and sustaining research capacity at both an individual and institutional level through the establishment of a clinical research network in India and describe the many challenges we faced and how we have tried to overcome them.

The INDOX Cancer Research Network

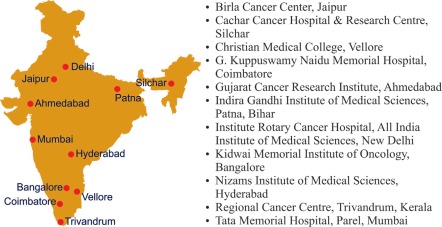

The INDOX (INDia–Oxford) Cancer Research Network was established in 2005 as a unique academic-industry partnership between the Institute for Cancer Medicine at Oxford University, six leading cancer centres in India. The network has now expanded to 12 centres (See Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The INDOX Cancer Research Network.

Our primary objectives were to enable Indian centres to conduct clinical research to the highest international standards; to ensure that trials were developed to address the specific needs of Indian patients by involving Indian investigators from the outset; and to provide the training to enable them to design and conduct their own studies.

We decided that it was important to work with industry from the outset, not just to fund the network but also because we could benefit from their expertise and experience in clinical research. It provided the means to sustain the network in the early years while we were building capacity after which time we were confident we would no longer be reliant on their funding. Most importantly, the funds enabled us to involve Indian investigators in developing a cancer research strategy for India which would ensure that protocols were developed for those cancers which had the greatest burden and the greatest unmet medical need.

Organisation and governance

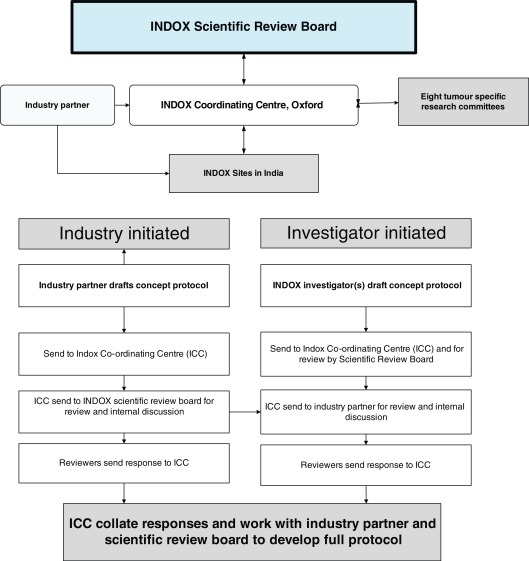

INDOX's governance structure was organised as an equal partnership, with joint leadership and joint development of research protocols. A Scientific Review Board was established which included all Indian PIs as well as representatives from Oxford. The review board worked with investigators and industry to develop both industry and investigator initiated trials according to the workflow expressed in Fig. 3. Eight tumour specific research committees, each chaired by a senior Indian PI, were then responsible for developing investigator-initiated protocols.

Fig. 3.

Organisation of INDOX network and development of clinical trial protocols.

Challenges, solutions and progress to date

In trying to build research capacity to design and execute epidemiological and clinical trials, we encountered a number of challenges at both the individual and institutional level. We present them here with the belief that such challenges and the solutions we implemented will have many commonalities with future similar programmes (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Practical challenges in conducting clinical research in India.

| Challenges | How they were overcome | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Limited experience in clinical trials prior to 2005 as India not bound by WTO/IPR rules and Indian pharma industry had focussed on development of generics. | Worked with industry partners to place clinical trials in India and thereby gain experience and build capacity for research. | Twenty-one trials conducted over last six years mainly in breast, head & neck, gastric and colorectal cancer. |

| No experience in Phase I trials as these were not allowed India prior to 2005. | Provided practical and theoretical training in conducting Phase 1 trials in Oxford and India. | Conducted one of the first Phase 1 trial in India from 2007 to 2009. |

| Lack of training opportunities, especially at the level of junior faculty, research nurses and pharmacists. | Provided a comprehensive training programme for all staff involved in clinical trials covering GCP, etc. ‘Train the trainers’ programme for principle investigators and site co-ordinators. | To date more than 100 PIs, coordinators and research nurses etc. attended training courses in Oxford and India. This is supplemented by distance learning through online courses. |

| GCP (Good Clinical Practice) only became part of Indian law in 2005 and centres in India did not have quality assurance standards in place. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) not in use in clinical trials units and those provided by industry not designed for use in Indian context. | All sites assessed for inclusion in network and monitored annually for quality assurance and compliance with GCP. Developed India-specific SOPs in collaboration with Indian sites. | Uniform quality standards with appropriate SOPs implemented across all sites. Monitoring has shown high quality trial practice and adherence to GCP and FDA audits have been passed. |

| Almost no experience of collaborative research with the vast majority of studies being small, single-centre studies and therefore often underpowered. | INDOX brought many investigators together for the first time to jointly design and conduct clinical studies, developing relationships through annual meetings and quarterly telephone conferences. | A condition of taking studies forward for support is that they must be multi-centric and studies are now conducted across all 12 sites. |

| PIs extremely busy with service and administration commitments. Large number of patients seen in each clinic making it difficult to devote time to explain trials to patients properly and ensure informed consent. | Appointed and trained dedicated site coordinators /research support officers whose role it is to support the PIs in all aspects of managing trials. | PIs have more time to spend explaining trial to patient and more time to work on actually designing and conducting their own trials. |

| Significant delays in gaining regulatory approval from Ministry of health Regulatory system, particularly for early phase trials. | Worked closely with Drugs Controller General of India to improve understanding of, and need for Phase 1 trials in India. | Successful in gaining regulatory approval for one of the first multinational Phase 1 trials in India. |

All sites now have dedicated clinical trials units and trained clinical research staff and are equipped to conduct trials to international (ICH-GCP) standards. Since 2005, INDOX has conducted 21 clinical trials in a number of different cancers, including one of the first multinational Phase 1 trials to be approved by the Indian regulatory authorities. From 2005–2007, all studies were industry sponsored with no Indian PIs but as the capacity, experience and expertise of the network increased, so the balance has shifted decisively to investigator initiated studies and in 2012, all INDOX studies will be led by Indian PIs, either working with industry or independently.

Ethical concerns

There continues to be a great deal of concern about the ethics of conducting clinical trials in India due to inadequate regulatory oversight and the potential risks of inadequately informed consent, inducement and exploitation, particularly of the poor and illiterate (13, 16).

In recognition of these challenges we only work with public or not-for-profit institutions which have independent ethics committees. We also assessed all centres before joining the network for compliance with ICH-GCP guidelines and provide training in the ethical conduct of clinical research on a continuing basis to all new and existing staff. We found that many of the informed consent forms (ICFs) for industry-sponsored trials were incomprehensible to many participants and therefore worked with colleagues in India to develop templates and SOPs to ensure that ICFs used appropriate language and terminology for the local context.

Due to the difficulty of ensuring that those who agree to take part in trials are both fully informed of, and understand, the risks and benefits of doing so, we are also conducting an audit of consent procedures to assess the motivation of clinical trial participants and to see how informed their consent really is. This study is being conducted in all Indian centres which are conducting clinical trials within the network and will help us to identify specific aspects of the consent process that require emphasis or fine-tuning to suit the requirements of Indian subjects. Furthermore, we hope that through this study we will be able to confirm or dispel the prevailing doubts that Indian patients are being exploited.

Conclusions and next steps

Over the past six years, INDOX has achieved many of its initial aims and objectives and has shown how research networks can be developed and sustained through academic-industry collaborations to the benefit of both parties (Fig. 4). However, much remains to be done, particularly in relation to prevention, early detection and developing affordable treatments which are accessible to even the poorest in India. To this end, we developed the ASCOLT trial in collaboration with the National Cancer centre in Singapore, a randomised controlled trial of Aspirin in the secondary prevention of colorectal cancer which is now being conducted with partners throughout Asia. We have also recently started the largest and first national study to investigate potentially modifiable risk factors for eight common cancers in India, the INDOX case-control consortium (17).

Fig. 4.

Professor Vinod Raina, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) New Delhi.

Although INDOX's activities to date have been confined to cancer in India, the model can be applied to any therapeutic or geographical area. We are therefore now establishing a similar network (building capacity for research in cancer and diabetes) across the Middle East, another region with a rapidly increasing burden of cancer and other NCDs but with limited clinical research experience and capacity (10).

INDOX is an innovative model for North–South cooperation in building capacity for clinical research and we believe that similar models could be successful in helping to tackle cancer and NCDs in other developing countries.

Conflict of interest and funding

RA has received research grants from GSK in 2005, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 2010 and research grants and honoraria from Sanofi in 2010 and 2011 and from Biogen Idec in 2007 and 2009. INDOX has received grants from GSK in 2005,6,7,8,9 and 2010 and Sanofi in 2010 which are ongoing and from Biogen Idec in 2007 and 2009. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Boyle P, Levin B. World cancer report. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer & World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, : systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allender S, Lacey B, Webster P, Rayner M, Deepa M, Scarborough P, et al. Level of urbanization and noncommunicable disease risk factors in Tamil Nadu, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:297–304. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.065847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinath Reddy K, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366:1744–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel V, Chatterji S, Chisholm D, Ebrahim S, Gopalakrishna G, Mathers C, et al. Chronic diseases and injuries in India. Lancet. 2011;377:413–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobias JS, Mittra I. Improving cancer care world wide. Ann Oncol. 1993;4:283–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masera G, Biondi A. Research in low-income countries. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:137–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008382631875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. World report on knowledge for better health : strengthening health systems; Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIH. International clinical research registry [Internet] Available from: www.Clinicaltrials.gov cited 31 October 2011.

- 10.Thiers FA, Sinskey AJ, Berndt ER. Trends in the globalization of clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:13–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dandona L, Katoch VM, Dandona R. Research to achieve health care for all in India. Lancet. 2011;377:1055–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62034-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magrath I. Building capacity for cancer control in developing countries: the need for a paradigm shift. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:562–3. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nundy S, Gulhati CM. A new colonialism? Conducting clinical trials in India. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1633–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arai RJ, Mano MS, de Castro G, Jr, Diz MDPE, Hoff PMG. Building research capacity and clinical trials in developing countries. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:712–3. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet] Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivasan S, Loff B. Medical research in India. Lancet. 2006;367:1962–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The INDOX Cancer Research Network [Internet] Available from: www.indox.org.uk cited 31 October 2011.