Abstract

The sequencing of numerous insect genomes has revealed dynamic changes in the number and identity of cytochrome P450 genes in different insects. In the evolutionary sense, the rapid birth and death of many P450 genes is observed, with only a small number of P450 genes showing orthology between insects with sequenced genomes. It is likely that these conserved P450s function in conserved pathways. In this study, we demonstrate the P450 gene, Cyp301a1, present in all insect genomes sequenced to date, affects the formation of the adult cuticle in Drosophila melanogaster. A Cyp301a1 piggyBac insertion mutant and RNAi of Cyp301a1 both show a similar cuticle malformation phenotype, which can be reduced by 20-hydroxyecdysone, suggesting that Cyp301a1 is an important gene involved in the formation of the adult cuticle and may be involved in ecdysone regulation in this tissue.

Introduction

Cytochrome P450s are an evolutionarily ancient gene family found in virtually all organisms [1]–[5]. P450s were originally characterised for their roles in the detoxification of xenobiotics, but further studies have shown that some P450s possess catalytic roles in the metabolism of many essential endogenous molecules [6]–[8]. In vertebrates, it has been suggested that evolutionarily conserved P450s function in endogenous pathways while those that are poorly conserved between species arise as evolutionary responses to xenobiotic challenges [9].

In insects, the number of cytochrome P450s in sequenced genomes ranges from 37 in the body louse, Pediculus humanus [10], to 160 in the dengue mosquito, Aedes aegypti [11]. Throughout evolution, selection results in tailoring an organism's genome. Thus genes involved in essential developmental processes are likely to be retained whereas those involved in specific detoxification responses, depending on an organism's environment, may not be under the same functional constraints. Some P450s are highly conserved and considered stable, with single orthologs found between species for those genes with proven biosynthetic and/or housekeeping roles [9]. Of the P450s conserved between D. melanogaster and A. aegypti [11], Cyp302a1, Cyp306a1, Cyp307a1, Cyp307a2, Cyp314a1, Cyp315a1 and Cyp18a1, are involved in the biosynthesis, activation and inactivation of the essential growth hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone [12]–[19], a conserved pathway found in all insects. Cyp4g1, which is involved in lipid metabolism [20] and Cyp4g15, which is expressed in the brain and central nervous system [21] are also both highly conserved in distant insect genomes.

In this study, we investigate Cyp301a1, another P450 found in all sequenced insect genomes to date. A previous study has shown that Cyp301a1 is expressed in both the embryonic and larval hindgut as well as the embryonic epidermis of D. melanogaster [22]. Here we show that Cyp301a1 is likely to possess an important function in the developing epidermis. RNAi knockdown of Cyp301a1, and a Cyp301a1 piggyBac element insertion mutant both result in adults with a cuticle defect. Histological analyses suggest a retention of larval epidermal cells down the central portion of the abdomen. As Cyp301a1 is a conserved P450 in insects, further investigations into Cyp301a1 function may reveal critical biochemical insights into the formation of the adult cuticle.

Materials and Methods

Phylogenetic analysis of Cyp301a1

The D. melanogaster Cyp301A1 predicted protein sequence was used as a query against representative databases from selected Diptera, Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera and Phthiraptera species using a BLASTp search (NCBI; http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/blast). Corresponding orthologs to both Cyp301A1 and Cyp301B1 were identified and annotated using Artemis [23]. The sequences were aligned using ClustalX [24] and a maximum likelihood tree (bootstrapping = 1000) was compiled using MEGA 5.05 [25]. D. melanogaster Cyp49A1 was used as an outgroup.

Drosophila stocks and vectors

The D. melanogaster stocks y; cn, bw; sp (stock number 2057), y1 w*; P{tubP-GAL4}LL7/TM3, Sb1 (stock number 5138), the piggyBac transposase stock w1118; CyO, P{Tub-PBac\T}2/wgSp-1 (stock number 8285) and the Cyp301a1 piggyBac insertion stock w1118; PBac{w+mC = WH}Cyp301a1f02301 (stock number 18537) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, Indiana. All stocks were maintained on glucose, semolina and yeast medium at 25°C. Drosophila transformation vectors were obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC), Indiana.

Synthesis of cDNA, real-time PCR and in situ hybridisation

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies). RNA samples were treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). cDNA was synthesised from 2 µg of each RNA sample in a 20 µl reaction using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and oligo(dT)20 primer following the supplier's instructions. Quantitative PCR (QPCR) was performed as previously described using RpL11 as a housekeeping gene [26]. Primers for QPCR of Cyp301a1 were Cyp301a1-RT-F (5′-ACCGCGAATACACTCCACTT-3′) and Cyp301a1-RT-R (5′-TGGCATCAGTCTCCATGTATT-3′). For in situ hybridisation, PCR was performed on cDNA using primers spanning the complete Cyp301a1 open reading frame (ORF) (Cyp301a1-ORF-F ATGAACAATCTGTCGCTGAAAGCTTGG and Cyp301a1-ORF-R CTAAACTCGTGTCATCTTAAAGCGCAG) and the PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). DIG-labeled RNA probe synthesis and in situ hybridisation were performed as previously described [22], [27]. In situ hybridisations were performed on the y; cn bw sp strain. Primers for Cyp4g1 and Cyp6g1 were previously reported [22], [26]. For adult integument RNA preparations, the integument was carefully removed from the inner abdominal layer and cDNA was synthesised using previously described methods.

RNAi knockdown experiments

The UAS-Cyp301a1-RNAi lines were constructed using the pWIZ vector [28]. BLASTn searches were performed on the ORF of Cyp301a1 to determine regions of similarity to other genes in the D. melanogaster genome. A region was chosen that contained less than 17 base pair sequence similarity to any other gene (to avoid off-targets) and that spanned between 300–500 base pairs. The sequence GGCCTCTAGA (which contains an XbaI cleavage site) was added to the end of both primers. Primers used were 5′-AAAGCTCCCTATTGGAGATACTTT-3′ and 5′-GTAGTCGCTTTAATTCCTCGTGAAC-3′. The fragment was amplified by PCR from cDNA using Expand High FidelityPLUS PCR system and cloned into pGEM-T Easy to confirm the correct sequence. The fragment was digested with XbaI before being cloned into pWIZ via the AvrII site. The construct was sequenced to determine the orientation of the inserted fragment before the second fragment was cloned into the NheI site. PCR and restriction digest confirmed that the second fragment to be cloned in the opposite orientation to form a hairpin. Transformation into D. melanogaster w1118 strain was performed using standard techniques.

Histological analyses

Adult female flies were taken within 24 hours of eclosion, partially dissected and fixed in formalin for at least eight hours at room temperature before being embedded in paraffin. Sections were performed using the cut-4060 microtome (Microtec) at 15 μm. Transverse sections were taken through the disrupted portion of the cuticle in Cyp301a1 f02301 flies and corresponding regions in controls. Sections were mounted on poly-lysine slides and either stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin or Calcofluor White (Sigma). Tissues were visualised using a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 microscope and a Leica SP5 confocal.

Excision of piggyback element from Cyp301a1 f02301

Cyp301a1 f02301 females were crossed to males from the piggyBac transposase strain w1118; CyO, P{Tub-PBac\T}2/wg[Sp-1]. F1 males (genotype w1118; Cyp301a1f02301/CyO, P{Tub-PBac\T}2 were then crossed to a double balancer strain (w1118; If/CyO; TM3, Sb/TM6B, Tb) to isolate transposition events and identified by progeny with white eyes. These flies were then made homozygous for the second chromosome (where Cyp301a1 is located) and analysed by PCR.

20-hydroxyecdysone exposure assays

Third instar larvae of the Cyp301a1 f02301 strain were exposed to 1 mg/ml 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) (Enzo Life Sciences) in instant fly media formula 4–24 (Carolina Biological Supply Company) as described previously [29]. Ten replicates of 10 larvae per vial were exposed to 20E, and the abdomen phenotype of all emerging flies was scored. Controls were reared under the same conditions but in the absence of 20E.

Results

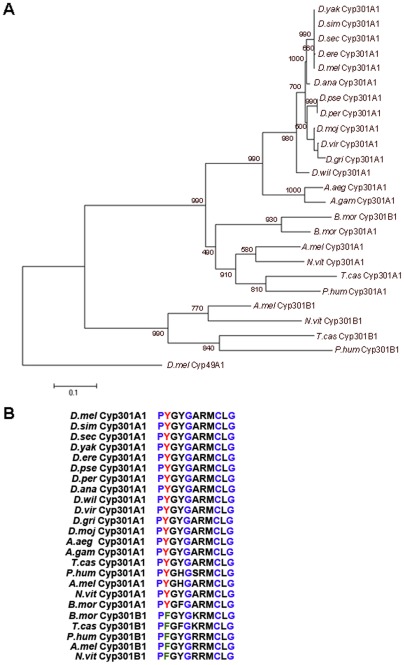

Cyp301a1 is evolutionarily conserved within insect species

To identify orthologs of D. melanogaster Cyp301a1, the predicted protein sequence was used to query the genomes of twelve Drosophila species as well as other related insect species. A single Cyp301a1 ortholog was found in each genome of the 12 Drosophila species with available sequence [30], as well as in representative genomes from sequenced insect orders [31]–[33]. Given the rapid evolution of most members of the P450 family, this conservation indicates the gene product has an important function in all insects. The inferred Cyp301 protein sequences were aligned and a phylogenetic analysis was performed. The tree shows an ancient duplication of the Cyp301 gene family prior to the divergence of the Phthiraptera species forming the Cyp301a1 and Cyp301b1 genes and then a subsequent loss of the Cyp301b1 copy in Diptera (Figure 1A). Interestingly, Cyp301A1 in all insect species analysed has a Tyr (Y) instead of the highly conserved Phe (F) present in the second position of the heme-binding domain (PFxxGxxxCxG) (Figure 1B). A Tyr in this position is not observed for any other D. melanogaster P450 [1]. Cyp301B1 orthologs do not possess this change in the heme-binding domain, suggesting some functional divergence between the Cyp301 genes following their duplication.

Figure 1. Cyp301a1 is a conserved insect P450.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of Cyp301A1 and Cyp301B1 in the insect species. Values shown represent 1000 bootstrapping values. D. melanogaster (D.mel) Cyp49A1 was used as an outgroup. D.ere = D. erecta, D.sec = D. sechellia, D.sim = D. simulans, D.yak = D. yakuba, D.ana = D. ananassae, D.per = D. persimilis, D.pse = D. pseudoobscura, D.gri = D. grimshawi, D.vir = D. virilis, D.moj = D. mojavensis, D.wil = D. willistoni, A.gam = A. gambiae, N.vit = Nasonia vitripennis, A.mel = Apis mellifera T.cas = Tribolium castaneum, B.mor = Bombyx mori, P.hum = Pediculus humanis. (B) Alignment of the heme-binding domain of Cyp301A1 and Cyp301B1 from representative insect species. Conserved residues in the heme-binding domain consensus sequence (PxxxGxxxCxG) are highlighted in blue. The conserved Phenylalanine (F) in the second position (highlighted in green) in Cyp301B1 orthologs is changed to a Tyr (Y) (highlighted in red) in all Cyp301A1 orthologs.

Temporal and spatial expression of Cyp301a1 during D. melanogaster development

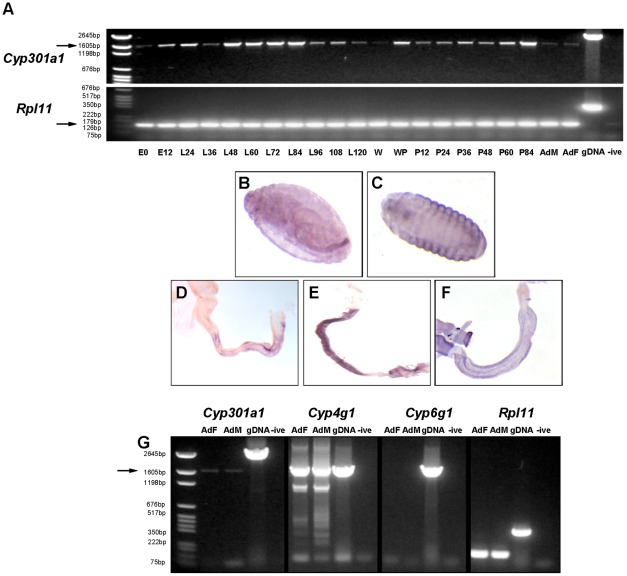

Cyp301a1 was detected by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR at all life stages, from embryo to adult (Figure 2A). Cyp301a1 expression is high during second instar larval stage (from L48), but decreases during the late third instar larval stage (L96-L120) and is essentially absent in wandering (W) larval stages (Figure 2A). Cyp301a1 expression then increases shortly during pupal formation (WP) and then again during late pupal development prior to eclosion (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Expression of Cyp301a1 in D. melanogaster.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of Cyp301a1 expression during the D. melanogaster development (expected size; cDNA = 1659 bp (arrow), gDNA = 2596 bp). Developmental stages are listed across the bottom of the gel in hours (E = embryo, L = larvae, W = wandering third instar, WP = white pupal stage, P = pupae, AdF = adult female, AdM = adult male). Animals were re-staged at onset of pupation. RPL11 was used as a housekeeping control gene and gDNA as a genomic DNA control (expected size; cDNA = 141 bp (arrow), gDNA = 355 bp). (B–F) In situ hybridisation of Cyp301a1. (B) At embryonic stages 13–16, Cyp301a1 is detected in the hindgut and (C) epidermis. Cyp301a1 is detected in the hindgut during (D) third instar larval, (E) pupal and (F) adult stages. (G) RT-PCR analysis of genes expressed in the adult integument. Cyp301a1 is detected in the adult female (AdF) and male (AdM) integument (arrow). Cyp4g1 (highly expressed in oenocytes which were included in integument dissections) is used as a positive control. Cyp6g1 is not detected in the integument samples (Chintapalli et al., 2007) and used as a negative control.

To examine the spatial expression of Cyp301a1, in situ hybridisation was performed on various stages during D. melanogaster development. Cyp301a1 expression in stage 1–2 embryos, the embryonic hindgut (stage 12–17) and epidermis (stage 17), as well as the larval hindgut has previously been characterised [22]. These expression patterns have been confirmed, and additional Cyp301a1 expression has been detected in the pupal and adult hindgut (Figure 2B–F). Cyp301a1 expression has also been reported in the larval trachea and larval carcass [34]. In addition, we detected Cyp301a1 expression by RT-PCR using cDNA synthesised from dissected adult integument (Figure 2G). To confirm the validity of this expression we also tested the expression of Cyp4g1 (known to be expressed in the oenocytes residing in the epidermis [22]), Cyp6g1 (a gene primarily expressed in the midgut, Malphigian tubules and fat body [26]) and the Rpl11 housekeeping gene (Figure 2G). As expected, Rpl11 and Cyp4g1 were expressed highly in both male and female integument samples whereas Cyp6g1 could not be detected from either cDNA sample (Figure 2G).

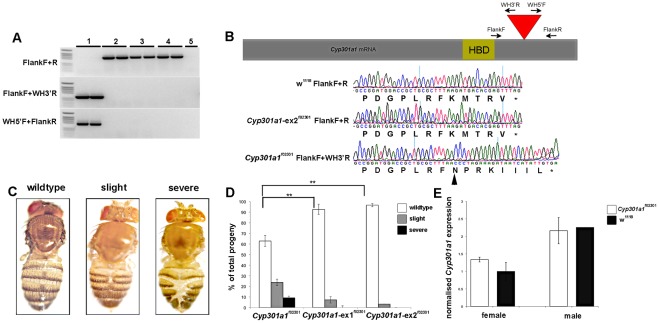

A piggyBac insertion in Cyp301a1 results in malformation of the adult cuticle

A transgenic D. melanogaster line, Cyp301a1 f02301 (PBac{WH}Cyp301a1f02301), contains a piggyBac element inserted within the Cyp301a1 predicted open reading frame [35]. Sequencing of the Cyp301a1 f02301 allele using primers specific to the piggybac element confirmed the presence of the WH-piggyBac element insertion, predicted to change the final five amino acids of the Cyp301A1 protein (Figure 3A, B). These changes are predicted to extend the C-terminal end of the protein by three amino acids and to increase the hydrophobicity of the protein, possibly altering the protein structure (Figure 3B). It is unknown if this results in a complete loss of function of the Cyp301A1 protein. Analysis of Cyp301a1 f02301 flies revealed a cuticle phenotype in both males and females, ranging from a slight malformation of the cuticle between the tergites to a complete loss of the tanned cuticle layer down the dorsal midline of the abdomen. The banding on the abdomen appeared severed, causing a misalignment of symmetry between the tergites. The range of phenotypes observed was classified into three categories; those that were wildtype (no visible disruption to the cuticle), slight (slight tearing of the cuticle down the mid-line) and severe (complete cuticle disruption) (Figure 3C). The Cyp301a1 f02301 flies also showed reduced survival with only 80% of larval forming pupae and of these, only 90% eclose to adults. Of the emerging progeny reared at 25°C, 63(±5)% showed no phenotype, 24(±4)% of progeny emerged with a slight cuticle phenotype and 10(±1.5)% of progeny emerged with a severe cuticle disruption (Figure 3D). We measured the Cyp301a1 mRNA levels by QPCR in Cyp301a1 f02301 adult flies (collected at eclosion) and found no significant difference compared to the background w1118 strain (Figure 3E), although we did detect higher Cyp301a1 expression in males than females. This suggests that the insertion is likely to affect Cyp301a1 protein stability or structure, rather than transcription.

Figure 3. Characterisation of the Cyp301a1 f02301 piggyBac insertion strain.

(A) PCR screen for the presence or absence of the piggyBac element in the Cyp301a1f02301 and excised (Cyp301a1-ex f02301 lines). There is no amplification of WH5′/3′ primers from lines without the piggyBac element. 1 = Cyp301a1f02301, 2 = w118, 3 = Cyp301a1-ex1f02301, 4 = Cyp301a1ex-2f02301, 5 = negative control) (B) Scheme of the Cyp301a1 mRNA sequence indicating the position of the piggyBac element in the Cyp301a1 gene (red triangle) just following the heme binding domain (HBD). The primers used for screening of the piggyBac insert are represented on the scheme. Below, chromatograms showing the base changes in the Cyp301a1f02301 strain (bases following black arrowhead) due to the piggyBac insertion compared to the w1118 background strain and excised lines. (C) The cuticle phenotype observed in the Cyp301a1 f02301 strain was divided into three categories based on phenotypic severity. (D) Quantification of the proportion of flies emerging from the Cyp301a1f02301 and Cyp301a1-excised f02301 lines according to the categories outlined in (C). **p<0.01 (E) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Cyp301a1 mRNA levels in Cyp301a1 f02301 and w1118 adult flies (collected at eclosion). Values are relative to RPL11.

To determine whether the cuticle phenotype seen in the Cyp301a1 f02301 line was due to a disruption of the Cyp301a1 gene, the piggyBac element was excised (Figure 3A). Two independent excised lines (Cyp301a1-ex1af02301 and Cyp301a1-ex2af02301) were obtained, which were screened by PCR and sequenced to confirm the presence of a functionally wild-type Cyp301a1 gene (Figure 3B). Unlike other eukaryotic class II transposons, piggyBac excisions are precise and do not leave a footprint [36]. Phenotypic analysis of the Cyp301a1-exf02301 flies raised at 25°C showed a significant decrease in appearance of the cuticle malformation phenotype and increase in the wild type phenotype compared to the Cyp301a1 f02301 line (Figure 3D).

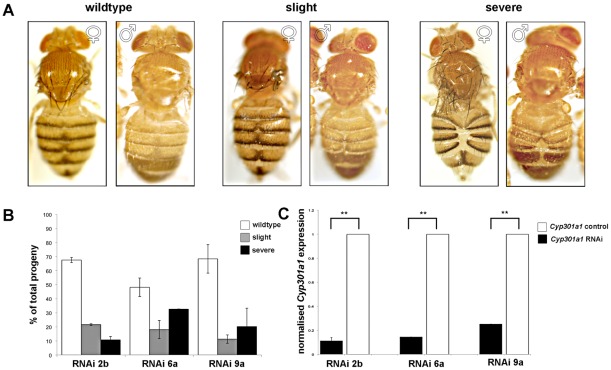

RNAi of Cyp301a1 results in similar cuticle phenotypes as Cyp301a1 f02301 lines

To further confirm that Cyp301a1 was causing the malformed cuticle phenotype, we constructed three independent RNAi lines targeted against Cyp301a1. When Cyp301a1 was silenced using the ubiquitous tubulin-GAL4 driver y1 w*; P{tubP-GAL4}LL7/TM3, Sb1 [37] and progeny were raised at 25°C, all Cyp301a1 RNAi progeny showed a similar range of cuticle phenotypes as seen in the Cyp301a1 f02301 flies (Figure 3A). QPCR on RNA isolated from adult males at eclosion showed that Cyp301a1 expression was significantly decreased (70–90%) in the Cyp301a1 RNAi progeny compared to controls (Figure 4C). Akin to the previous phenotypic classifications used, Cyp301a1 adult progeny were classed in order of cuticle phenotype severity (Figure 4A). At 25°C, 61(±7)% of flies emerged with no phenotype, 17(±3)% of RNAi progeny emerged with a slight cuticle malformation and 22(±7)% of RNAi progeny emerged with a severe cuticle phenotype from all three lines (Figure 4B). The cuticle phenotype was equally prevalent in males and females (Figure 4A). These RNAi results corroborate those reported for the Cyp301a1 f02301 insertion strain, suggesting that a loss of Cyp301a1 is likely to be responsible for the cuticle malformation.

Figure 4. Characterisation of the phenotype observed in Cyp301a1 RNAi progeny.

(A) Phenotypes of Cyp301a1 RNAi driven by the tubulin-GAL4 driver were characterised as described in Figure 3. Both males and females are shown. (B) Quantification of the proportion of flies emerging from the Cyp301a1 RNAi lines, according to the categories outlined in A. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR of Cyp301a1 in three independent Cyp301a1 RNAi lines (2b, 6a and 9a). Values are relative to RPL11 and normalised to Cyp301a1 expression in each of the controls (Cyp301a1 control). **p<0.01.

Cyp301a1 f02301 flies show a cellular defect in adult cuticle formation

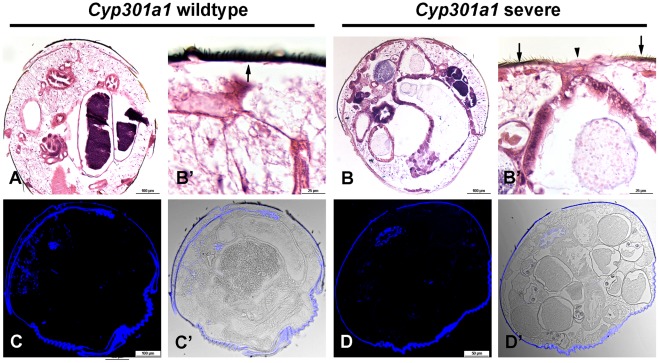

To further understand the cellular pathology observed in the Cyp301a1 f02301 flies, transverse sections of the abdominal cuticle at eclosion were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Although there is a lack of cells in the central region, there appears to be an intact cuticle layer (albeit thinner and nonpigmented), which spans the two sides of the tergites in Cyp301a1 f02301 flies (Figure 5B,B′). Calcofluor staining shows that chitin is not secreted in these areas, although the remaining cuticle appears correctly pigmented, similar to control sections (Figure 5C,D). Compared to control flies, where transverse sections clearly show an even distribution of abdominal sensory bristles lining the cuticle layer (Figure 5A,A′), in Cyp301a1 f02301 flies there appears to be a lack of abdominal sensory bristles in regions surrounding the central cavity, where this cuticle is improperly formed (Figure 5B,B′). The lack of sensory bristles in this central region may suggest a failure of proper histoblast migration, given that abdominal histoblasts are also responsible for correct formation of sensory bristles along the abdomen.

Figure 5. Histological analysis of Cyp301a1f02301 flies showing a severe cuticle phenotype.

(A-B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of sections. (A and enlarged in A′) Transverse section through the abdomen of a Cyp301a1 control sample shows a normal, pigmented cuticle layer lining the abdomen (arrow). (B and enlarged in B′) Transverse section through the abdomen of a Cyp301a1f02301 sample shows a central unpigmented layer, in the region where the cuticle is disrupted (arrowhead). The surrounding cuticle looks wild type (arrows). (C) Calcofluor staining (blue; overlayed with brightfield in C′) of transverse sections from Cyp301a1 control samples showing staining across the cuticle. (D) Calcofluor staining (blue; overlayed with brightfield in D′) of transverse sections from Cyp301a1f02301 samples showing staining across the cuticle. but is absent from the central regions where the cuticle is disrupted.

The Cyp301a1 cuticle malformation phenotype can be reduced by 20-hydroxyecdysone

20E pulses during insect development define periods of growth and metamorphosis [38]. During larval stages, imaginal discs express high levels of Ecdysone Receptor (EcR), which when bound by 20E, is involved in the transcriptional activation of many genes [39]. 20E is likely to mediate both the destruction of unwanted larval tissues and simultaneous differentiation of adult tissues [40]. It was shown recently that an early peak of 20E during the prepupal stage activates the synchronous division of histoblasts while a later peak is essential for larval cell replacement [41].

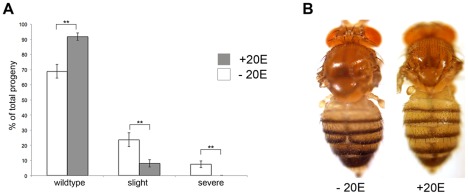

To determine whether the cuticle phenotype observed in the Cyp301a1 RNAi and Cyp301a1 f02301 flies was dependent on 20E, flies were raised on a diet supplemented with 20E. Cyp301a1 f02301 larvae fed 20E during development eclosed with a significantly reduced incidence of the severe and mild abdominal phenotype, and significantly increased incidence of the wild type cuticle phenotype when compared with those fed control food (Figure 6). This suggests that Cyp301a1 may be involved in ecdysone regulation during adult cuticle formation.

Figure 6. Rescue of Cyp301a1f02301 flies using 20E.

(A) Quantification of the proportion of flies emerging from the Cyp301a1f02301 line with or without 20E treatment, according to the categories outlined in Figure 3A. **p<0.01. (B) Phenotypes of Cyp301a1f02301 flies at eclosion with or without 20E treatment.

Discussion

Insect cytochrome P450s are a large gene family, with roles in development and xenobiotic detoxification [1], [42]. Despite the large numbers of P450s found in insects, the number of orthologous P450s conserved between insects is small. In general, it has been observed that conserved P450s have developmental roles, such as the P450s involved in 20E biosynthesis in D. melanogaster and Manduca sexta, [43]–[45]. The conservation of Cyp301a1 in insects indicates that Cyp301a1 is likely to play an important role. Phylogenetic analyses show that Cyp301a1 possesses a restricted pattern of evolution, typical for many stable P450s [9]. A single Cyp301a1 ortholog is present in 12 Drosophila species with sequenced genomes [30]. Interestingly the Tyr to Phe change, conserved in the heme-binding domain of CYP301A1 orthologs is not found in CYP301B1 sequences, the nearest ortholog. Although sequence changes in the conserved heme-binding domain of P450s are rare, they are characteristic for P450s that act as atypical monooxygenases, for example CYP74A, a plant allene oxide synthase, and CYP5A1, the vertebrate thromboxane synthase enzyme [1], [46].

Cyp301a1 is expressed in a number of tissues throughout D. melanogaster development. It is expressed in the larval, pupal and adult hindgut, the epidermis of stage 17 embryos and in the larval trachea and carcass [34]. Disruption of Cyp301a1 function, as demonstrated by both Cyp301a1 piggybac and RNAi knockdown experiments, produced adult flies with a distinct morphological disruption to the cuticle. Histological analyses revealed an improper fusion of tergites along the abdomen, which may be caused by an abnormal proliferation of the adult cuticle. This phenotype is significantly reduced in the Cyp301a1 RNAi control groups, and the Cyp301a1-exf02301 strains, suggesting that the cuticle malformation is specifically due to a disruption in Cyp301a1 function.

The cuticle malformation phenotype, although replicable in both genotypes, showed incomplete penetrance with approximately 60% of flies affected in each case. This incomplete penetrance could be due to variability in the loss of Cyp301a1. RNAi of Cyp301a1 results in a decrease of Cyp301a1 mRNA levels of 70–90% as measured by QPCR, and it is not known if the Cyp301a1 piggyBac insertion completely abolishes CYP301A1 function. A more extreme phenotype may result if a Cyp301a1 null allele is created. Alternatively, the incomplete penetrance could result from a redundancy in Cyp301a1 function. Several other P450s, such as Cyp49a1 and Cyp18a1 are expressed in the integument during Drosophila development [19], [22]. Although Cyp301a1 is highly conserved and thus likely to possess an essential function, additional P450s may be able to partially compensate for the reduced function of Cyp301a1 in the Cyp301a1 f02301 and Cyp301a1 RNAi flies.

A similar abdominal phenotype has been documented and is caused by a lack of larval epidermal cell (LEC) replacement, which obstructs the closure of the adult abdominal epithelium [29], [41]. Usually, newly formed adult abdominal tergites arise during metamorphosis as polyploid LECs are replaced by the descendants of the histoblasts imaginal cells, derived from small lateral nests in the larva. The histoblasts divide and migrate dorsally and ventrally over the abdomen until its whole surface is covered with cells [41], [47]–[48]. During this process, the LECs undergo apoptosis; they constrict apically, are extruded from the epithelium and are subsequently phagocytosed [41]. Sustained expression of Activating transcription factor 3 (Atf3) alters the adhesive properties of LECs, thus preventing their extrusion and replacement by the adult epidermis [29]. Removal of LECs is normally complete by 36 hours after pupal formation, at which time sheets of histoblasts reach the dorsal midline [49]. Atf3 expression is high during early larval development and is downregulated during early pupal formation with a late peak of expression just prior to eclosion [49], a similar expression profile to Cyp301a1. Retention of LECs caused by sustained atf3 expression appears to be Jun-mediated and can be partially rescued with the addition of 20E [29]. Similarly, we also supplied ecdysone via this feeding method [29] to Cyp301a1 f02301 flies, which seems to allow progression through development without inhibiting adult ecdysis (as seen when 20E is administered via injection). Survival could be seen because the actual concentration that is entering larvae (assuming the larvae are only exposed when feeding, and not at later life stages) was not high enough to alter metamorphosis, and this concentration is not maintained during pupal development. Our experiments show that 20E exposure during third instar larval stage partially rescues the abdominal closure defects in Cyp301a1 f02301 flies, possibly due to altering the early 20E peak. 20E is also involved in activating several genes in the chitin biosynthesis pathway, forming the polysaccharide layer in the cuticle [50]. However, given that intact regions of chitin are present in the Cyp301a1 RNAi and Cyp301a1 f02301 flies, it is unlikely that CYP301A1 is involved in chitin synthesis.

Although we cannot conclude that CYP301A1 is directly involved in 20E regulation, it is not unprecedented for P450s to be involved in 20E regulation during development. Cyp302a1, Cyp306a1, Cyp307a1, Cyp307a2, Cyp314a1 and Cyp315a1 are all involved in the biosynthesis and activation of the essential growth hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone [12]–[18] while Cyp18a1 is involved in the inactivation of 20E [19]. Mutants in Cyp18a1 affect the timing and shaping the 20E peaks during metamorphosis [19]. As the inactivation of ecdysteroids possibly involves more than one enzyme, with ecdysteroid metabolic breakdown products located in the gut and other tissues [51], it is possible that Cyp301a1 is somehow involved in ecdysteroid metabolism, or perhaps some other aspect of 20E signalling or regulation during adult cuticle formation.

Acknowledgments

The Australian Drosophila Biomedical Research Support Facility is acknowledged for providing Drosophila services. Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center are acknowledged for providing Drosophila stocks.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian Research Council through an Australian Research Fellowship to PJD. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Feyereisen R. Insect Cytochrome P450. In: Gilbert LI, Iatrou K, Gill SS, editors. Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science. Elsevier; 2005. pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis DF. 57 varieties: the human cytochromes P450. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;5:305–318. doi: 10.1517/phgs.5.3.305.29827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson DR. Metazoan cytochrome P450 evolution. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1998;121:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0742-8413(98)10027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson DR, Schuler MA, Paquette SM, Werck-Reichhart D, Bak S. Comparative genomics of rice and Arabidopsis: Analysis of 727 cytochrome P450 genes and pseudogenes from a monocot and a dicot. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:756–772. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werck-Reichhart D, Feyereisen R. Genome Biol 1, REVIEWS; 2000. Cytochromes P450: a success story.3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert LI. Halloween genes encode P450 enzymes that mediate steroid hormone biosynthesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;215:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoilov I. Cytochrome P450s: coupling development and environment. Trends Genet. 2001;17:629–632. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Hull AK, Gupta NR, Goss KA, Alonso J, et al. Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3100–3112. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas JH. Rapid Birth-Death Evolution Specific to Xenobiotic Cytochrome P450 Genes in Vertebrates. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Kang JS, Min JS, Yoon KS, Strycharz JP, et al. Decreased detoxification genes and genome size make the human body louse an efficient model to study xenobiotic metabolism. Insect Mol Biol. 2010;19:599–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strode C, Wondji CS, David JP, Hawkes NJ, Lumjuan N, et al. Genomic analysis of detoxification genes in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavez VM, Marques G, Delbecque JP, Kobayashi K, Hollingsworth M, et al. The Drosophila disembodied gene controls late embryonic morphogenesis and codes for a cytochrome P450 enzyme that regulates embryonic ecdysone levels. Development. 2000;127:4115–4126. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namiki T, Niwa R, Sakudoh T, Shirai K, Takeuchi H, et al. Cytochrome P450 CYP307A1/Spook: a regulator for ecdysone synthesis in insects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ono H, Rewitz KF, Shinoda T, Itoyama K, Petryk A, et al. Spook and Spookier code for stage-specific components of the ecdysone biosynthetic pathway in Diptera. Dev Biol. 2006;298:555–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petryk A, Warren JT, Marques G, Jarcho MP, Gilbert LI, et al. Shade is the Drosophila P450 enzyme that mediates the hydroxylation of ecdysone to the steroid insect molting hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13773–13778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336088100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rewitz KF, Gilbert LI. Daphnia Halloween genes that encode cytochrome P450s mediating the synthesis of the arthropod molting hormone: evolutionary implications. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren JT, Petryk A, Marques G, Jarcho M, Parvy JP, et al. Molecular and biochemical characterization of two P450 enzymes in the ecdysteroidogenic pathway of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11043–11048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162375799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren JT, Petryk A, Marques G, Parvy JP, Shinoda T, et al. phantom encodes the 25-hydroxylase of Drosophila melanogaster and Bombyx mori: a P450 enzyme critical in ecdysone biosynthesis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:991–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guittard E, Blais C, Maria A, Parvy JP, Parishna S, et al. CYP18A1, a key enzyme of Drosophila steroid hormone inactivation, is essential for metamorphosis. Dev Biol. 2011;349:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutierrez ED, Wiggins D, Fielding B, Gould AP. Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature. 2007;445:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nature05382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maibeche-Coisne ML, Monti-Dedieu S, Aragon S, Dayphin-Villemant C. A new cytochrome P450 from Drosophila melanogaster, CYP4G15, expressed in the nervous system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:1132–1137. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung H, Sztal T, Pasricha S, Sridhar M, Batterham P, et al. Characterization of Drosophila melanogaster cytochrome P450 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5731–5736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompso, JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, et al. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung H, Bogwitz MR, McCart C, Andrianopoulos A, ffrench-Constant RH, et al. Cis-regulatory elements in the Accord retrotransposon result in tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila melanogaster insecticide resistance gene Cyp6g1. Genetics. 2007;175:1071–1077. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.066597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sztal T, Chung H, Gramzow L, Daborn PJ, Batterham P, et al. Two independent duplications forming the Cyp307a genes in Drosophila. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:1044–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YS, Carthew RW. Making a better RNAi vector for Drosophila: use of intron spacers. Methods. 2003;30:322–329. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekyrova P, Bohmann D, Jindra M, Uhlirova M. Interaction between Drosophila bZIP proteins Atf3 and Jun prevent replacement of epithelial cells during metamorphosis. Development. 2010;137:141–150. doi: 10.1242/dev.037861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark AG, Eisen MB, Smith DR, Bergman CM, Oliver B, et al. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The International Aphid Genomics Consortium IAG. Genome sequence of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS biology. 2010;8:e1000313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feyereisen R. Evolution of insect P450. Biochemical Soc Trans. 2006;34:1252–1255. doi: 10.1042/BST0341252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkness EF, Haas BJ, Sun W, Braig HR, Perotti MA, et al. Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic lifestyle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12168–12173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003379107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JA. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thibault ST, Singer MA, Miyazaki WY, Milash B, Dompe NA, et al. A complementary transposon tool kit for Drosophila melanogaster using P and piggyBac. Nat Genet. 2004;36:283–287. doi: 10.1038/ng1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horn C, Offen N, Nystedt S, Hacker U, Wimmer EA. piggyBac-based insertional mutagenesis and enhancer detection as a tool for functional insect genomics. Genetics. 2003;163:647–661. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riddiford LM. London: Academic Press; 1994. Advances of Insect Physiology.213 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao TP, Segrave WA, Oro AE, McKeown M, Evans RM. Drosophila ultraspiracle modulates ecdysone receptor function via heterodimer formation. Cell. 1992;71:63–72. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90266-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milner MJ. The eversion and differentiation of Drosophila melanogaster leg and wing imaginal discs cultured in vitro with an optimal concentration of beta-ecdysone. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1997;37:105–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ninov N, Chiarelli DA, Martin-Blanco E. Extrinsic and intrinsic mechanisms directing epithelial cell sheet replacement during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development. 2007;134:367–379. doi: 10.1242/dev.02728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic resistance to synthetic and natural xenobiotics. Annu Rev Entomol. 2007;52:231–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rewitz KF, Rybczynski R, Warren JT, Gilbert LI. Developmental expression of Manduca shade, the P450 mediating the final step in molting hormone synthesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;247:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rewitz KF, Rybczynski R, Warren JT, Gilbert LI. Identification, characterization and developmental expression of Halloween genes encoding P450 enzymes mediating ecdysone biosynthesis in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rewitz KF, Rybczynski R, Warren JT, Gilbert LI. The Halloween genes code for cytochrome P450 enzymes mediating synthesis of the insect moulting hormone. Biochemical Soc Trans. 2006;34:1256–1260. doi: 10.1042/BST0341256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li L, Chang Z, Pan Z, Fu ZQ, Wang X. Modes of heme binding and substrate access for cytochrome P450 CYP74A revealed by crystal structures of allene oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13883–13888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804099105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madhaven MM, Madhaven K. Morphogenesis of the epidermis of adult abdomen of Drosophila. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1980;60:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roseland CR, Schneiderman HA. Regulation and metamorphosis of the abdominal histoblasts of Drosphila melanogaster. Dev Genes Evol. 1979;186:235–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00848591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bischoff M, Cseresnyes Z. Cell rearrangements, cell divisions and cell death in a migrating epithelial sheet in the abdomen of Drosophila. Development. 2009;136:2403–2411. doi: 10.1242/dev.035410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yao Q, Zhang D, Tang B, Chen J, Chen J, et al. Identification of 20-hydroxyecdysone late-response genes in the chitin biosynthesis pathway. PLoS One. 2010;18:e14058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lafont R, Dauphin-Villemant C, Warren JT, Rees H. Ecdysteroid Chemistry and Biochemistry. In: Gilbert L, Gill SS, editors. Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science. Oxford: Elseveir; 2005. pp. 125–195. [Google Scholar]