Abstract

Aims:

To determine the effects of combined in-patient rehabilitation with a home-based program on function and quality of life.

Setting and Design:

Tertiary care, university teaching hospital, randomized controlled trial.

Patients and Methods:

Thirty admitted patients with congestive heart failure with New York Heart Association class II -IV. A five step individualised phase-1 cardiac rehabilitation program followed by a structured home based rehabilitation for eight weeks was given to the experimental group while the control group only received physician directed advice. Six minute walk distance was assessed at discharge and follow-up, while quality of life (SF36) was assessed at admission, discharge, and follow-up.

Statistical analysis used:

Independent t-test, paired t-test and repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis.

Results:

At admission patients in both the groups were comparable. After the phase-1 cardiac rehabilitation, there was a change in the six minute walk distance between control and experimental group (310 m vs. 357 m, respectively; P = 0.001). Following the eight week home-based program, there was a greater increase in six minute walk distance in the experimental group when compared to the control group (514 m vs. 429 m; P < 0.001). Quality of life as measured by the SF-36 at the end of 8-weeks showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in the experimental group for both the mental and physical components.

Conclusion:

Early in-patient rehabilitation followed by an eight week home based exercise program improves function and quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure.

Keywords: Congestive heart failure, early mobilisation, home based rehabilitation, quality of life, six minute walk distance

INTRODUCTION

Congestive heart failure is a clinical syndrome, which consists of a triad of symptoms, namely, heart failure at rest or exercise, objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction at rest and/or response to treatment towards heart failure.[1]

Home-based programs have been gaining popularity over the last decade with majority of the studies being done In USA, UK and Canada.[2] A recent Cochrane review by Taylor et al., found that home based and institution based rehabilitation programs were equally effective in improving health related quality of life among patients with myocardial infarction.[3] With regard to heart failure, a review by Hwang et al., found that home-based programs increase exercise capacity and endothelial function safely.[4]

Recently, the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation has recommended that “In-patient rehabilitation should begin as soon as possible after hospital admission”.[5] Yet, there are no studies on the early in-patient phase of rehabilitation among patients with congestive heart failure. Insufficient studies also exist from the Asian sub-continent with regard to both in-patient and home-based cardiac rehabilitation. In a country where patients need to pay for their healthcare, cost effective treatments remain a priority in the management of patients in this part of the world.

In order to meet the rehabilitative need of patients with congestive heart failure in India, it was felt that it is necessary to ascertain whether results from Western data on home-based programs can be extrapolated to our population. To achieve this aim, a hypothesis was generated, taking into consideration a void in literature with regard to early in-patient rehabilitation. The objective of the study was therefore to find the effects of combined in-patient rehabilitation with a structured home-based program on function and quality of life among patients with congestive heart failure.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

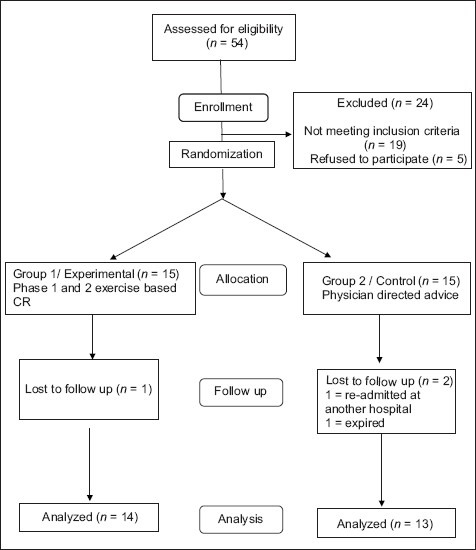

The study was cleared by the Institutional Ethical Committee and written informed consent obtained. The study was also registered on the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2008/091/000298). A prospective randomized controlled trial was done on 30 admitted patients with congestive heart failure with NYHA class II-IV assuming that the null hypothesis was true. Patients were randomly allocated to either a control or experimental group through concealed allocation using block randomization. Patients with acute myocardial infarction, uncontrolled tachyarrhythmias, severe orthopedic and neurological problems and severe valvular disease were excluded from the study.

The sample size for this study was calculated using the comparison of means to determine a difference of 100m on the six minute walk test (6MWT) while keeping the power of the study at 80% at a 95% confidence interval. Considering a drop-out rate of 20%, a total of 15 subjects in each arm were required.

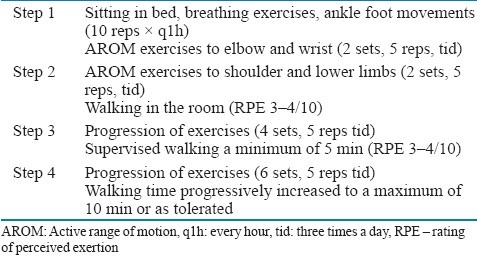

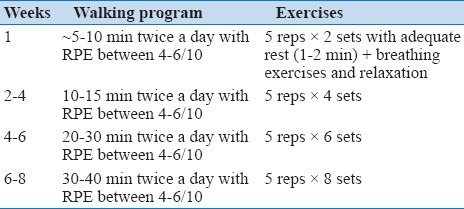

Patients in the experimental group received a physical therapist supervised in-patient phase-1 cardiac rehabilitation program [Table 1], which was followed by a structured eight-week phase-2 home based program [Table 2]. During phase-1, patients were exercised under supervision and monitoring. Exercises were prescribed using the modified Borg's rating of perceived exertion (RPE) between 3-4/10 during this phase. The various steps served as a guide for which to progress the patients and this was individualised for each patient. If a patient was able to perform a particular step without any discomfort, a faster progression was made. On the contrary, if a patient was not able to perform at a particular level, the progression was not made until the patient was comfortable at that level. The patient's relatives were also encouraged to be a part of the rehabilitation program and were educated on the importance of exercise. Patients and their relatives were taught to identify heavy exertion (RPE >7) and chest pain (>5 on the visual analogue scale) so that exercises could be terminated. These same scales were also utilised during the home-based program.

Table 1.

Four step phase-1 cardiac rehabilitation protocol

Table 2.

Structured home-based program

The control group received physician directed advice on ambulation during their stay. At discharge, they were given advice on staying active by the treating physician.

At discharge, both the groups were administered the six minute walk test (6 MWT) according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines.[6] The experimental group was provided a detailed home based program which consisted of upper and lower limb exercises and a walking program guided by RPE. The phase-1 program familiarised these patients to the exercises to be followed during the home program. They were also provided an exercise log book which was required to be filled by the patient daily. They were checked by the therapist at the end of eight weeks to assess the adherence to the program; adherence was defined for this study as having performed exercises for >80% of the days. The therapist in charge of the program progressed the exercises and walking distance weekly after having a telephonic conversation with the patient. The control group received only regular advice from the treating physician and no rehabilitation was given to the patients during the course of the study.

Quality of life (QoL) was assessed at the time of admission, discharge and at eight-weeks follow up using the medical outcome survey short form-36 (SF-36).[7] The six minute walk distance (6 MWD) was assessed at discharge and follow-up. It was not assessed at admission as acute heart failure is a contraindication to the test.

All patients were managed as per the American Heart Association guidelines for the management of heart failure and also by the same physician during the entire study period.[8] All patients were started on anti-platelets, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and digoxin. Beta-blockers were prescribed only where indicated.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 16.0 statistical package was used for the analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the baseline characteristics and appropriate measures of central tendency and dispersion were used according to the distribution of the outcome. Normality was checked using the Shapiro Wilk test. Univariate analysis was done using independent t-test and paired t-test for between and within the group differences. The non-parametric equivalent, i.e., Mann Whitney U test and the Wilcoxon Signed rank test, was used if the data was non-normal (NYHA grading). Multivariate analysis was done using the repeated measures ANOVA (RANOVA) to assess for overall effect on QoL. Post-hoc analysis using the Bonferroni analysis was done for the variables which showed a statistically significant difference. Statistical significance was considered if P < 0.05 at 80% power.

RESULTS

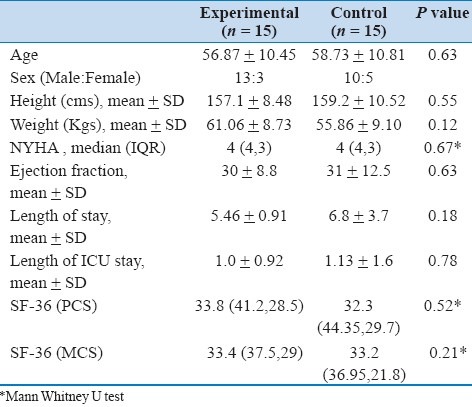

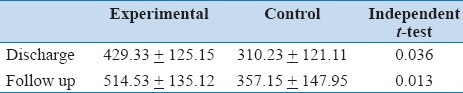

Thirty patients were recruited to this study, and the flow is shown in the flow diagram as per the CONSORT statement [Figure 1].[9] The mean age of persons in this study was 57.7 ± 10.4 years (range 31 to 85 years) with males more affected (22/30) [Table 3]. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups at baseline for the various outcome measures. The mean ejection fraction was 31 ± 10%. However, both the groups were similar in cardiac function as seen from the ejection fraction (P < 0.05). At discharge, there was a statistically significant difference seen between the groups for 6MWD (P < 0.05) which showed a higher distance walked in the group receiving phase-1 CR. At discharge, 13 patients in the experimental group were in NYHA class II with two continuing to be in class IV. Those in class III were able to complete stage 4 of the in-patient rehabilitation program while those in class IV were able to complete stages 2 or 3.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 3.

Demographics of patients at admission

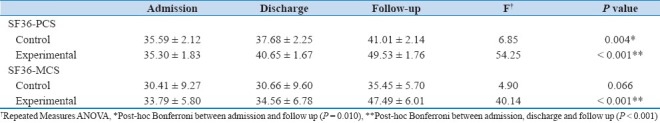

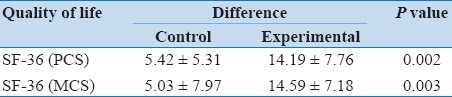

Changes in the SF36 scores were compared across admission, discharge and follow-up using the RANOVA. A statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) was seen for the physical and mental component on the SF36 [Table 4]. A post-hoc analysis found a significant change between admission and follow up for the PCS in the control group while in the experimental group, there was a significant difference between all the three time points for both the PCS and MCS [Table 4]. The difference in QoL scores from admission to follow up showed a statistical significance when compared between the groups for the PCS and MCS scores on the SF36 [Table 5]. Changes in general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health also showed a statistically significant difference with rehabilitation.

Table 4.

Quality of life scores during the study period

Table 5.

Differences in QoL scores between the groups from baseline to follow-up

The 6MWD was seen to improve by 90.39 ± 0.42m in the experimental group while in the control group it was only 52.65 ± 0.46m [Table 6]. Statistical significance was also seen on the paired t-test (P < 0.05). No adverse events occurred during the course of the training program or during the administration of the 6MWT.

Table 6.

Six minute walk distance (in meters) at discharge and follow up

DISCUSSION

This study was a randomized controlled trial on patients with congestive heart failure to determine the effects of an in-patient rehabilitation followed by a home-based program on function. The study found significant changes in the six minute walk distance and the quality of life following the home-based rehabilitation program. In a developing country like India, where cost of treatment is a major concern, the use of home based rehabilitation programs would play a great role in improving function and QoL among patients with congestive heart failure.

A significant difference with regard to functional capacity and QoL has been seen in this study after eight weeks of training. This is similar to previous study wherein improvements in functional capacity were found after two months of training.[10] An 18% change in peak oxygen uptake has been seen in patients with congestive heart failure after an eight week home based training program.[11] Belardinelli et al., found that after the initial two months, there was no further increase in functional capacity with a maintenance program for 24 months.[10] This highlights the importance of having patients engage in an exercise program for at least eight weeks in order to achieve improvements in functional capacity. A study by Omar et al., found that community based approach to patients with congestive heart failure improved QoL and 6MWD at six months.[12] These findings were also seen in the home based setting in two months.

Improvement in 6MWD was seen at follow-up following the home based rehabilitation program. This suggests an improvement in functional capacity in just eight weeks. A study by Berent et al., found that the physical working capacity improved in just 25 days with a residential program.[13] However, with regard to home-based programs, it is still not clear as to how many days are required for benefits to occur.

The adherence rate observed in this study among those in this study among those excising was found to be 72.6%. The reason for this rate of adherence could be due to the weekly telephone conversations and follow-up with the patient. This was a major difference from what was used in the HF-ACTION study wherein telephone calls were made once every two weeks to once every three months.[14] However, better methods to assess adherence would be required and it will be worth studying the benefits of pedometers in the Indian setting to guide exercises among patients with congestive heart failure.

Barriers to this home-based program were assessed through a semi-structured interview on the 14 patients who completed the rehab program. The main barriers seen were fear (10/14), lack of interest (7/14), lack of motivation (6/14), and family fears and concerns (9/14). These factors would need to be taken in account when prescribing a home-based program to patients with congestive heart failure in India.

This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first of its kind in India, wherein an early phase-1 program has been followed by a structured home based program. From this study, it is clear that an early rehabilitation program begun once the patient is medically stable is of great importance in improving walking distance and physical components on the SF-36. These benefits can be sustained if accompanied by a structured home-based program for eight weeks. Significant improvements in QoL and 6MWD were seen during this period in both the groups; however, the changes were more in the experimental than the control group. This shows that cardiac rehabilitation along with optimal drug therapy is essential for improving QoL and function among patients with congestive heart failure.

Long term follow-up after cessation of this eight week program would provide valuable data regarding the carry-over effect. It would also be interesting to note the number of persons who did continue to follow the exercises and whether such programs are beneficial and feasible for patients within India and others South Asian countries, where the cost of treatment is a major concern for the patient.

CONCLUSION

A combined in-patient, exercise based, cardiac rehabilitation program followed by a structured home based program, improves function and quality of life among patients with congestive heart failure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge Ms. Prachi Shah and Mr. Saurab Naik for all their help in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray JJ, Ponikowski P, Poole-Wilson PA, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2388–442. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark AM, Haykowsky M, Kryworuchko J, MacClure T, Scott J, DesMeules M, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized control trials of home-based secondary prevention programs for coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:261–70. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32833090ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor RS, Dalal H, Jolly K, Moxham T, Zawada A. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD007130. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang R, Redfern J, Alison J. A narrative review on home-based exercise training for patients with chronic heart failure. Phy Ther Rev. 2008;13:227–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piepoli MF, Corra’ U, Benzer W, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Dendale P, Gaita D, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:1–17. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283313592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. Writing on behalf of the 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult writing committee. 2009 Focused update: ACCF/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belardinelli R, Georgiou D, Cianci G, Prcaro A. Randomized, controlled trial of long term moderate exercise training in chronic heart failure. Effects of functional capacity, quality of life and clinical outcomes. Circulation. 1999;99:1173–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coats AJ, Adamopoulos S, Radaelli A, McCance A, Meyer TE, Bernardi L, et al. Controlled trial of physical training in chronic heart failure: Exercise performance, hemodynamics, ventilation, and autonomic function. Circulation. 1992;85:2119–131. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.6.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omar AR, Suppiah N, Chai P, Chan YH, Seow YH, Quek LL, et al. Efficacy of community-based multidisciplinary disease management of chronic heart failure. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:528–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berent R, von Duvillard SP, Crouse SF, Auer J, Green JS, Sinzinger H, et al. Short term residential cardiac rehabilitation reduces B-type natriuretic peptide. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:603–8. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832d7ca8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1439–1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]