Abstract

Introduction:

As chest pain is an important symptom of coronary artery disease (CAD), the presentation of the symptom often prompts referral to a cardiologist for further investigation. The aim of the present study is to determine the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients referred to a cardiology outpatient clinic for performing the stress test.

Patients and Methods:

Two hundred and fifty consecutive outpatients referred for evaluation of chest pain by the stress test at a government cardiology clinic from April 2010 to November 2010 were asked to participate in the study. We estimated the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms, as assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, in a sample of patients with chest pain.

Results:

The prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms was estimated to be 42% and 31%, respectively, in the total chest pain population. Males with abnormal test were depressed but females experienced more anxiety symptoms. Patients with negative tests had significantly higher scores for anxiety and higher depression scores than those with positive tests. Eleven percent of the patients with positive tests were women and 23% were men.

Conclusion:

Determining a patient's anxiety disorder history may assist the clinician in identifying, especially, women with angina who are at a lower risk of underlying CAD.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, exercise test

INTRODUCTION

As chest pain is an important symptom of coronary artery disease (CAD), the presentation of the symptom often prompts referral to a cardiologist for further investigation.

However, often, no organic pathology is found. Besides, patients with chest pain but no evidence of heart disease, as a group, have an excellent prognosis for survival and a future risk of cardiac morbidity similar to that reported in the general population.[1] These patients continued to have poor quality of life and social and occupational disability. Both physical and psychological factors have been studied as suggested causes of chest pain.

Microvascular angina, mitral valve prolapse, esophageal motility disorders, hyperventilation syndromes and chest wall syndromes have been suggested as physical causes. As it is possible to treat these disorders effectively, their recognition is important.

However, the disorder is rarely recognized by physicians.[2] Possible reasons for that, in addition to lack of knowledge about the disorder, may be lack of validated screening instruments.

Furthermore, physicians may be reluctant to enquire about the psychological symptoms in these patients, as it has been supposed that patients are defensive about symptoms being due to mental illness.[2] With this background, the present study was designed to determine the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients referred to a cardiology outpatient clinic for performing the stress test.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Ethics

The research protocol was accepted by the Regional Ethics Committee, Yasouj, in April 2010.

Study population

Two hundred and fifty consecutive outpatients referred for evaluation of chest pain by the stress test at a government cardiology clinic from April 2010 to November 2010 were asked to participate in the study. Fifty-eight patients were excluded from the study because of exclusion criteria. The fact that the referring physician had evaluated the patients’ chest pain as sufficiently suspect to necessitate referral for investigation by a cardiologist was taken as adequate for study inclusion. Patients were included in the study according to the following inclusion criteria:

No prior documented organic heart disease

Aged 18–65 years

No psychosis

No contraindication for stress test

Cannot achieve 85% maximum heart rate or non-conclusive results

In the present cross-sectional study, we estimated the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms, as assessed by the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), in a sample of patients with chest pain.

Instrument used anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed with the HADS, designed to measure the cognitive symptomatology of depressed mood and anxiety.[3,4] The HADS is a well-validated measure and has been used extensively in other chronic disease populations. The HADS was developed by Zigmond and Snaith in 1983 to provide clinicians and scientists with a reliable, valid and practical screening tool for identifying the two most common forms of psychological distress in medical patients – anxiety and depression.[3] The scale consists of 14 items and measures two constructs, anxiety and depression, with cut-off points for severity (scores: 0–7 normal; 8–10 borderline and 15–21 case).[3] A chest pain form was filled out by the cardiologist for each patient during the cardiac evaluation.

The form was constructed by the investigators to obtain data of patients’ previous or current medical diseases, current medication and risk factors for CAD (family history, smoking habits, diabetes, treated hypertension, hyperlipidemia). According to these data, patients underwent physical examination, and if there is no contraindication for exercise stress test, then they are referred for it. Those who cannot tolerate the stress test were excluded from the study.

In all patients, a Bruce protocol stress test[4] was performed. The cardiologist conducting the test interpreted the result. The test was considered positive for CAD1 if ST-segment depression of 1 mm occurred in any of the electrocardiogram leads during the exercise.[5]

In addition, the appearance of typical chest pain and decrease in systolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg during exercise would contribute to the diagnosis.

With none of these signs present, the test was considered negative for CAD.[6] The cardiologists were not informed of the results of the psychiatric interviews. For the purpose of final diagnostic classification, all chest pain forms and results of the cardiologic investigations were reviewed by an independent cardiologist, blind to the results of the psychiatric interview. This review did not lead to any changes in the initial classification of diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms were estimated using the HADS cut-off points for “mild to severe anxiety and depression scores (scores 8–10 mild, 11–14 moderate and 15–21 severe).”

Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used to compare the levels of anxiety and depression in the different subgroups of patients with chest pain. The anxiety and depression scores were dichotomized by the following cut-off points prior to regression analyses: 8–21 for mild to severe anxiety/depression scores versus 0–7 for a normal score.

The odds ratios (OR) for mild to severe anxiety and depression were estimated using logistic regression with adjustment for relevant confounders. Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit was run on the fully adjusted anxiety and depression models to check for an adequate fit of the data. In the logistic regression analyses, the effect of adjustment for age and gender are shown separately from the fully adjusted model to enhance the transparency of the analysis. All tests were two-tailed. The difference was considered statistically significant when P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Questionnaires were filled by patients before entering the examination room, and the overall response rate was 100% (n=192).

Prevalence of anxiety and depression

The prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms was estimated to be 42% and 31%, respectively, in the total chest pain population. In total, 15% of the study population had an abnormal stress test. Of the 192 included patients, 65% were women and 35% were men. Age ranged from 20 to 65 years, with a mean of 50.4 years. Patients with abnormal HADS scores were significantly younger (mean age 35 ± 10.0 vs. 54 ± 8 years, P = 0.01), more likely to be female [in the anxiety group 50% (62) vs. 29% (20), P = 0.02 and in the depressed group 35.0% (44) vs. 25% (17), P = 0.04].

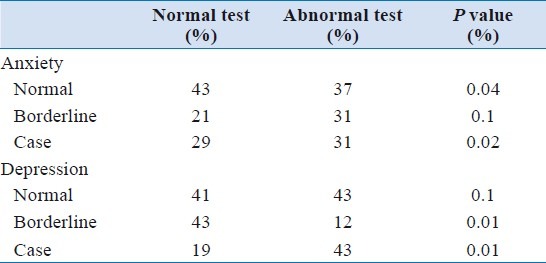

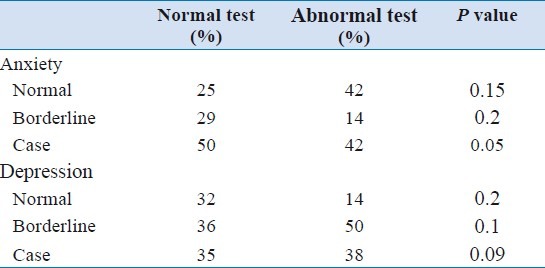

There were no significant differences in marital status. The prevalence of “mild,” “moderate” and “severe” anxiety and depression scores, by gender and cardiovascular status, are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Prevalence of anxiety–depressive symptoms in the male population

Table 2.

Prevalence of anxiety–depressive symptoms in the female population

The prevalence of “mild” anxiety in females with a normal test was more than double that of females with an abnormal test, and men with normal test experienced more “moderate” to “severe” anxiety compared with men with an abnormal test, but they were more depressed. We also found differences between cardiovascular status and gender: males with an abnormal test were depressed but females experienced more anxiety symptoms. Patients with negative tests had significantly higher scores for anxiety and higher depression scores than those with positive tests. Eleven percent of the patients with positive tests were women compared with 23% men. The probability of a negative test in patients without anxiety or depression who had typical pain was 8% in males and 32% in females. The probability of a negative test in patients who were both anxious and depressed and had atypical pain was 97% in males and 99% in females.

Medical assessment

Of the 192 patients who could tolerate the exercise stress test, 15% had an abnormal stress test. Significantly, patients with abnormal HADS scores were registered positively for current smoking [57.9% (44/76) vs. 34.1% (42/123), P = 0.001)]. A significant difference was also found for the mean number of risk factors (2.2 ± 1.3 vs. 2.1 ± 1.1, P = 0.02), while no statistically significant differences were found for single risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, high glucose and lipid profiles.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence estimates of anxiety and depression symptoms in general population samples are approximately 7.0% for anxiety and 6.8% for depression, based on the DSM–IV criteria.[7] The prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients in our study was more than triple that of the general population estimates. These findings confirm that patients referred for outpatient heart examination because of chest pain frequently meet the criteria for psychosomatic disorders. Only 15% of the patients had a positive stress test, while 65% of the patients met the evidence of high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Anxiety and, particularly, depression, at presentation and later, were significantly associated with severe symptoms. Patients with chest pain associated with neurosis and depression are not reassured by physiological stress testing because their physical symptoms are a feature of the underlying psychiatric disease.[8]

Determining a patient's anxiety disorder history may assist the clinician in identifying, especially, women with angina who are at a lower risk of underlying CAD.[8] It seems likely that diagnostic exercise testing in patients with both affective symptoms and atypical chest pain may be unhelpful, misleading and uneconomical. Again, we must emphasize on the role of behavioral cardiology. It is an emerging field of clinical practice based on the recognition that adverse lifestyle behaviors, emotional factors and chronic life stress can all promote atherosclerosis and adverse cardiac events.[9]

Study limitations

We cannot exclude the possibility that patients experiencing anxiety and depression are overrepresented in our sample and may introduce potential bias as those who responded possibly experienced symptoms of anxiety and depression. The sociodemographic and clinical data were self-reported by the patients. Ideally, we should have validated the patient-reported information against their medical records, but were not able to do so because of time and resource limitations.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cannon RO. Microvascular angina and the continuing dilemma of chest pain with normal coronary angiograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:877–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutledge T, Reis SE, Olson M, Owens J, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, et al. History of anxiety disorders is associated with a decreased likelihood of angiographic coronary artery disease in women with chest pain: the WISE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:780–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Ebrahimi M, Jarvandi S. The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benhorin J, Pinsker G, Moriel M, Gavish A, Tzivoni D, Stern S. Ischemic threshold during two exercise testing protocols and during ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:671–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90175-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janszky I, Ahnve S, Lundberg I, Hemmingsson T. Early-onset depression, anxiety, and risk of subsequent coronary heart disease: 37-year follow-up of 49,321 young Swedish men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, van Hemert AM. Somatoform disorders in general practice.Prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Channer KS, James MA, Papouchado M, Rees JR. Failure of a negative exercise test to reassure patients with chest pain. Q J Med. 1987;63:315–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, Saab PG, Kubzansky L. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: The emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:637–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]