Abstract

Dipping smokeless tobacco (ST) is used worldwide. We report a case of acute myocardial infarction in a young patient, who consumed smokeless tobacco (Sweka) for over one year. ST may be as harmful as smoking and carries adverse cardiac complications. A prompt call for restriction and prohibition is advised and its alternative use to quit smoking must be abandoned.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Niswar, smokeless tobacco, Sweka

INTRODUCTION

The consumption of tobacco is a major source of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Tobacco is consumed in two forms: the smoked tobacco products, like cigarettes and shisha (water pipe) and the smokeless tobacco (ST). Smokeless tobacco forms are chewing, dipping, and snuff tobacco. Dipping tobacco, also known as moist snuff or spit tobacco, is held in the mouth between the cheeks and gums instead of being smoked. The dip rests on the inside lining of the mouth usually for a period depending on the user's preference, between few minutes to an hour. Nicotine is absorbed by the oral mucosa.

The ST is primarily used in Central Asia, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, India, and in Europe, like Sweden.[1] It carries different names: ‘Snus’ or ‘Snuff’ is a well-known name in Sweden, ‘Niswar’ (Naswar) or ‘Tombaco’ is used in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India, ‘toombak’ in Sudan, and ‘Sweka’  or ‘Niswar’ in the Gulf Region.

or ‘Niswar’ in the Gulf Region.

The prevalence of ST use in India is 20%, and significantly higher in males.[2] In the United States, 5.2% of young adults, between the ages of 18 and 25, and 3.2% adults over the age of 26, used ST in 2006.[3] In Sweden, around 20% of the adults used ST.[4]

There are no precise figures available on the exact prevalence of ST usage in the gulf region, but most observers agree that is widely used by workers coming from Asia, and it has been recently noticed that these products have gained popularity among adult and adolescent citizens.

Many factors contribute to the popularity of ST consumption. Proliferation of restrictions on the smoking area is the main reason behind many people using ST, especially for the young, below 18 years of age. Other reasons are that it is presumed to be a less harmful alternative for those having difficulty quitting smoking and its easy affordability.

We report the case of a young man who presented with acute myocardial infarction. A thorough review of the risk factors profile revealed heavy ST use for one year. The effects and consequences of ST are discussed.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 21-year-old man presented with central chest pain that awakened him from sleep two hours before, associated with nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and shortness of breath. He had used dipping ST in the form of Niswar (Sweka) five to ten times per day [Figure 1] continuously for one year, which was preceded by the habitual use of both types of smoking for another year. There was no past history of cardiac disease, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, drug abuse or family history of coronary artery disease.

Figure 1.

Dipping smokeless tobacco in the form of Niswar (Sweka)

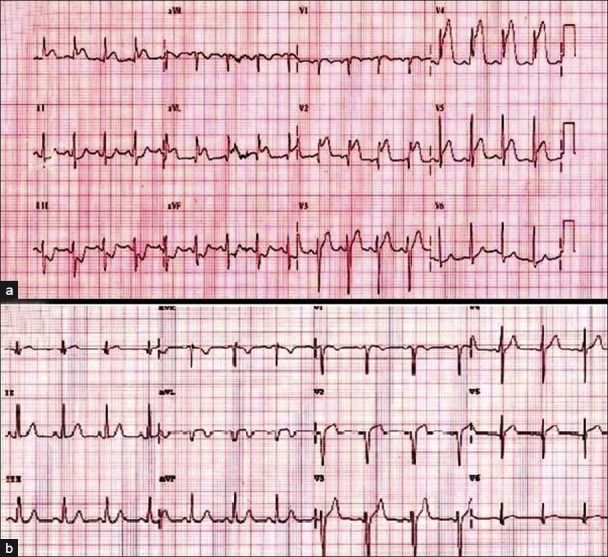

On physical examination the heart rate was 100 beats / minute, regular, and the blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg. The remaining physical examination was unremarkable. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST elevation in leads V2-V5, I, AVL with reciprocal ST-segment depression in leads II, III, and AVF [Figure 2a]. The chest X-ray was normal. In the first few minutes of presentation, the patient developed cardiac arrest due to ventricular tachycardia (VT), which rapidly disintegrated to ventricular fibrillation. The patient was successfully resuscitated.

Figure 2.

(a) A 12-lead electrocardiogram shows ST elevation in leads V2 – V5, I, and AVL, with reciprocal ST-segment depression in leads II, III, and AVF. (b) Patient's electrocardiogram after successful fibrinolyitic therapy

Fibrinolyitic therapy was given at presentation as well as intravenous nitrate and heparin. Oral aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, and statin were also instituted.

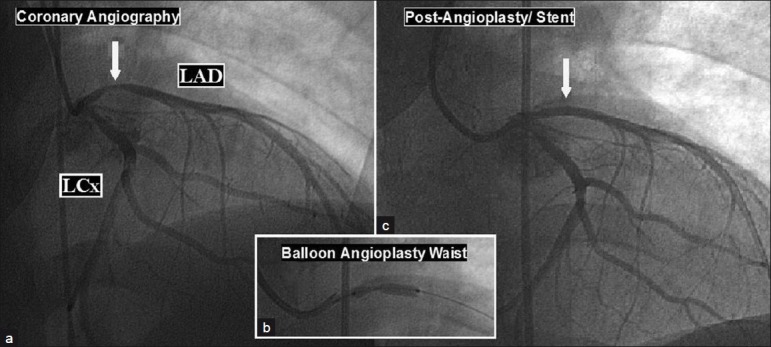

The patient responded successfully to fibrinolyitic therapy. The chest pain subsided and ST elevation was markedly reduced after 30 minutes [Figure 2b]. Apart from short runs of nun-sustained VT, he remained asymptomatic until the third hospital day, when the chest pain reappeared and a coronary angiogram was performed which revealed a 70% proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) lesion, 40% left circumflex artery (LCX) lesion, and a normal right coronary artery [Figure 3a]. Even though the patient was on continuous intravenous nitrate, further intra-coronary nitrate failed to relieve a presumed coronary spasm. Angioplasty was performed and followed by a bare metal stent implantation for the culprit lesion in the LAD [Figures 3b and c]. The laboratory tests showed a peak in the troponin-T level, of 5.056 ng / ml (normal < 0.1 ng / ml), and creatine kinase MB of 350.6 u / l (normal < 24 u / l). Blood urea, glucose, and electrolytes were normal. The drug screen for cocaine, amphetamine, ethanol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, methadone, opiates, phencyclidine, propoxyphene, and tetrahydrocannabinol was negative. The thrombophilia screen for Factor V Leiden mutation, antiphospholipid antibodies, proteins C and S, and antithrombin levels was negative. Transthoracic echocardiography during admission revealed left ventricular segmental wall motion abnormalities and an ejection fraction of 28%.

Figure 3.

(a) Coronary angiogram reveals a 70% proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) lesion and LCX: left circumflex artery; (b) Angioplasty shows the waist; (c) LAD after stent implantation.

DISCUSSION

Many studies have shown contradictory results with regard to the cardiovascular effects of ST. Some have reported an association between ST and cardiovascular complications.[5–7] Some studies showed lower risk in comparison to those who smoked tobacco,[8,9] while some studies failed to find such an association.[10–12] Bolinder et al.,[7] reported an increased prevalence of circulatory disorders as well as cardiovascular mortality among Snuz users in 1994, but in this study the tobacco-specific nitrosamine content of the Swedish Snus was substantially reduced through changes in the manufacturing process.[6] While, more recently Hergens et al., found no increased risk of MI from Swedish Snus (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.90 – 1.10), the risk of fatal MI was higher among heavy users (≥ 50 g per day) (RR 1.96; 95% CI1.08 – 3.58).[5,11]

The cardiovascular short-term effect of ST use have been documented. The effects produced by nicotine were an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, plus an increase in cardiac stroke volume and coronary blood flow, as well as vasoconstriction.[13,14] Nicotine is the main component of tobacco and is found to reach a higher concentration in ST users in comparison to smokers.[15] Furthermore, the endothelial dysfunction, which is a risk factor for MI, was found to be caused by ST use.[16] Hergens, hypothesized that the direct cardiovascular effect of nicotine could be the cause behind the severity of MI, and oral moist snuff contained substances such as fatty acids and flavonoids that could have a protective effect for MI, while, carbon monoxide, oxidant gases, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were substances present in cigarettes. These substances and not nicotine could be the cause of an increase in the risk of MI among smokers.[5,7]

Although it has not been reported before with ST use, coronary artery spasm caused by smoking is well-recognized specially in young patients.[17,18] A presentation we thought the patient had coronary spasm and he was kept on nitrate infusion. The failure to respond to intracoronary nitrate during angiography and the clear balloon waist during dilatation of the LAD lesion raised the possibility of atherosclerotic plaque rupture behind the MI. Coronary spasm due to illicit drug abuse was excluded angiographically, as well as by negative history and an unrevealing drug screen.

The absence of clear risk factors for CAD in this patient, except for ST use, draw attention to the likelihood of rapid acceleration and / or enhanced vulnerability of atherosclerosis attributable to ST use.

Due to the lack of information about the constituents of different types of ST in different countries, the previous impression that ST is less harmful should be handled carefully and abandoned until further studies are conducted.

CONCLUSION

Smokeless tobacco is as harmful as smoking. Its alternative use to quit smoking needs to be handled carefully. A prompt call for restriction and prohibition is advised.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maher R. Chewing of various types of quids in Pakistani population and their.associated lesions. Dent J Malaysia. 1997;18:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rani M, Bonu S, Jha P, Nguyen SN, Jamjoum L. Tobacco use in India: Prevalence and predictors of smoking and chewing in a national cross sectional household survey. Tob Control. 2003;12:e4. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockville, MD: DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4293; 2007. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates C, Fagerstrom K, Jarvis M, Kunze M, McNeill A, Ramstrom L. European Union policy on smokeless tobacco: A statement in favor of evidence based regulation for public health. Tob Control. 2003;12:3607. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hergens MP, Alfredsson L, Bolinder G, Lambe M, Pershagen G, Ye W. Long-term use of Swedish moist snuff and the risk of myocardial infarction amongst men. J Intern Med. 2007;262:351–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Connell C, Calle EE. Two large prospective studies of mortality among men who use snuff or chewing tobacco (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:347–58. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-5519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolinder G, Alfredsson L, Englund A, de Faire U. Smokeless tobacco use and increased cardiovascular mortality among Swedish construction workers. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:399–404. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asplund K. Smokeless tobacco and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45:383–94. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2003.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolinder G. Overview of knowledge of health effects of smokeless tobacco.Increased risk of cardiovascular diseases and mortality because of snuff. Lakartidningen. 1997;94:3725–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huhtasaari F, Lundberg V, Eliasson M, Janlert U, Asplund K. Smokeless tobacco as a possible risk factor for myocardial infarction: A population based study in middle-aged men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1784–90. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hergens MP, Ahlbom A, Andersson T, Pershagen G. Swedish moist snuff and myocardial infarction among men. Epidemiology. 2005;16:12–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147108.92895.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janzon E, Hedblad B. Swedish snuff and incidence of cardiovascular disease.A population-based cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fant RV, Henningfield JE, Nelson RA, Pickworth WB. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of moist snuff in humans. Tob Control. 1999;8:387–92. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westman EC. Does smokeless tobacco cause hypertension.? South Med J. 1995;88:716–20. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holm H, Jarvis MJ, Russell MA, Feyerabend C. Nicotine intake and dependence in Swedish snuff takers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;108:507–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02247429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohani M, Agewall S. Oral snuff impairs endothelial function in healthy snuff users. J Intern Med. 2004;255:379–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiishi M, Takatsu F. Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for coronary spasm. Circulation. 1993;87:76–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey MR, Valentin V, Hunt D, et al. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: A case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368:647–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]