Abstract

Background

Voltage-gated (Cav) Ca2+ channels are multi-subunit complexes that play diverse roles in a wide variety of tissues. A fundamental mechanism controlling Cav channel function involves the Ca2+ ions that permeate the channel pore. Ca2+ influx through Cav channels mediates feedback regulation to the channel that is both negative (Ca2+-dependent inactivation, CDI) and positive (Ca2+-dependent facilitation, CDF).

Scope of Review

This review highlights general mechanisms of CDI and CDF with an emphasis on how these processes have been studied electrophysiologically in native and heterologous expression systems.

Major Conclusions

Electrophysiological analyses have led to detailed insights into the mechanisms and prevalence of CDI and CDF as Cav channel regulatory mechanisms. All Cav channel family members undergo some form of Ca2+-dependent feedback that relies on CaM or a related Ca2+ binding protein. Tremendous progress has been made in characterizing the role of CaM in CDI and CDF. Yet, what contributes to the heterogeneity of CDI/CDF in various cell-types and how Ca2+-dependent regulation of Cav channels controls Ca2+ signaling remain largely unexplored.

General Significance

Ca2+ influx through Cav channels regulates diverse physiological events including excitation-contraction coupling in muscle, neurotransmitter and hormone release, and Ca2+-dependent gene transcription. Therefore, the mechanisms that regulate channels, such as CDI and CDF, can have a large impact on the signaling potential of excitable cells in various physiological contexts.

Voltage-gated (Cav) Ca2+ channels are multi-subunit complexes that play diverse roles in a wide variety of tissues. Multiple Cav channels have been characterized (Cav1.x-Cav3.x, Table 1), which are comprised mainly of a pore-forming α1 subunit and for Cav1 and Cav2 channels, auxiliary Cavβ and α2δ subunits [1]. Cav channels are generally named according to the identity of the α1 subunit such that Cav1.2 channels are those containing the α11.2 subunit. Mutations in the genes encoding Cav α1 cause severe human disorders including migraine, deafness, epilepsy, autism, cardiac arrhythmia, malignant hyperthermia and periodic paralysis [2–4]. Cav channels mediate an inward Ca2+ current that not only depolarizes the cell membrane potential but also provides an intracellular Ca2+ signal that can activate gene transcription, protein phosphorylation, and neurotransmitter release. Therefore, factors that modulate Cav channel properties can significantly affect cellular excitability and signal transduction.

Table 1.

Classification and expression of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels1

| CavX.X | α1 subunit2 | Current3 | Primary tissue distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | α1S | L-type | Skeletal muscle |

| 1.2 | α1C | L-type | Heart, nervous system, endocrine glands |

| 1.3 | α1D | L-type | Heart, nervous system, endocrine glands, inner ear |

| 1.4 | α1F | L-type | Retina, T-cells |

| 2.1 | α1A | P/Q-type | Nervous system |

| 2.2 | α1B | N-type | Nervous system |

| 2.3 | α1E | R-type3 | Nervous system |

| 3.1 | α1G | T-type | Nervous system, heart |

| 3.2 | α1H | T-type | Nervous system, heart, adrenal gland |

| 3.3 | α1I | T-type | Nervous system |

A fundamental mechanism controlling Cav channel function involves the Ca2+ ions that permeate the channel pore. Ca2+ influx through Cav channels mediates feedback regulation to the channel that is both negative (Ca2+-dependent inactivation, CDI) and positive (Ca2+-dependent facilitation, CDF). CDI and CDF have been described mainly for “high voltage-activated” Cav1 and Cav2 Ca2+ channels both in native cell-types and heterologous expression systems. CDI and some forms of CDF depend on calmodulin (CaM) binding to the pore-forming Cav α1 subunit. This review will highlight current understanding of the general mechanisms of CDI and CDF with an emphasis on how these processes have been studied electrophysiologically in native and heterologous expression systems.

Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI)

Inactivation represents a non-conducting state of many ion channels that is favored by multiple mechanisms. For Cav channels, sustained or very positive depolarization promotes voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI). However, Cav channel inactivation can also occur via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism, which is evident as a faster decay of the Cav current when Ca2+ rather Ba2+ is used as the charge carrier during sustained depolarizations (Fig. 1a). This was first demonstrated in voltage clamp recordings of Paramecium [5, 6], in which Ca2+ influx through Cav channels regulates reorientation of cilia and swimming in reverse [7]. In addition to faster inactivation of Ca2+ currents (ICa) compared to Ba2+ currents (IBa), inactivation correlated with the amplitude of the peak ICa. This hallmark of CDI is readily studied in double-pulse voltage-protocols, where the effects of a conditioning (inactivation-inducing) prepulse are reflected in the amplitude of a subsequent test current evoked at a single voltage. A plot of the normalized test ICa amplitude vs. prepulse voltage is bell-shaped, with greatest inactivation at the prepulse voltage eliciting the maximal inward Ca2+ current (Fig. 1b). By contrast, inactivation of IBa using this protocol should be relatively minor, increasing monotonically with the membrane potential. For such measurements of CDI, the duration of the conditioning prepulse should be short enough to promote greater CDI than VDI, which generally occurs on a longer timescale for most Cav1 and Cav2 channels.

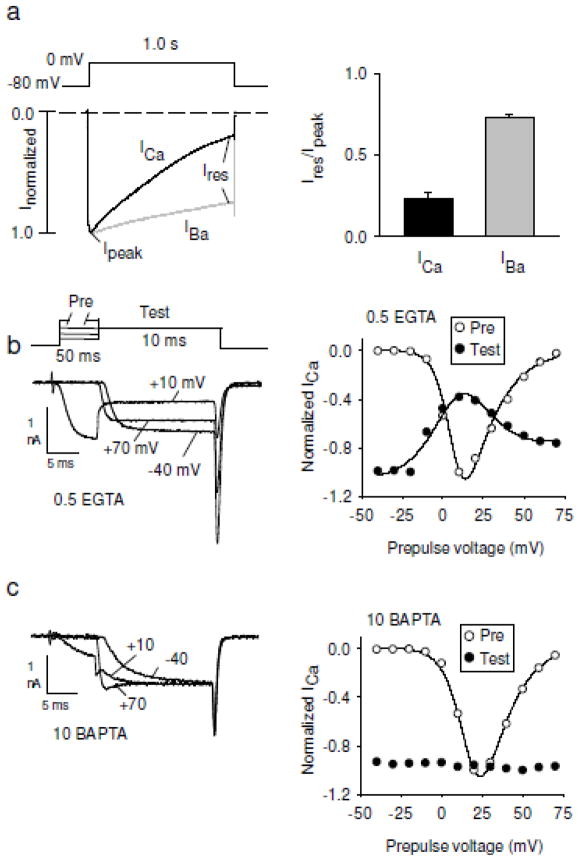

Figure 1.

Characterization of CDI of Cav2.1 channels in voltage-clamp recordings. a) Comparison of inactivation of ICa (black trace) and IBa (grey trace) in HEK293T cells transfected with Cav2.1 (α12.1, β2A and α2δ). Currents are evoked by 1-s pulses from −80 mV to 0 mV. Extracellular solution contains 10 mM Ca2+ or Ba2+ and intracellular solution contains 0.5 mM EGTA. Right, inactivation is measured by dividing residual current amplitude (Ires) by the peak amplitude (Ipeak). b,c) Double pulse protocol for measuring CDI. Left, ICa is evoked by a 10-ms test pulse after a conditioning prepulse to various voltages as indicated. Right, normalized ICa for the test and prepulse are plotted against prepulse voltage. With physiological Ca2+ buffering (0.5 mM EGTA, b) but not with higher levels of Ca2+ buffering (10 mM BAPTA, c), maximal CDI of the test current occurs at prepulse voltages evoking peak inward current.

In their recordings of Paramecium, Brehm and Eckert also showed that strong buffering of intracellular Ca2+ greatly inhibited inactivation of ICa, suggesting that Ca2+ accumulation in the cell was necessary for CDI ([5, 6]; Fig. 1b,c). However, as will be discussed, the extent to which Ca2+ chelators suppress CDI varies between Cav channel classes. Nevertheless, these classical studies of Paramecium defined approaches for characterizing Cav channel CDI, which has proven a fundamental form of negative feedback in various cell types and organisms [8–11]. The mechanisms and properties of CDI vary between Cav channel classes and between cell-types, which may have important physiological consequences.

Cav1.2

Cav1 channels mediate L-type Ca2+ currents in muscle, nerve, and endocrine cells (Table 1). Of the four classes of Cav1 channels, Cav1.2 is the most ubiquitously expressed [12]. Cav1.2 regulates excitation-contraction coupling in the heart, which may explain why genetic inactivation of this channel in mice causes embryonic lethality [13]. In ventricular myocytes, Cav1.2 mediates L-type ICa that contributes to the plateau depolarization (phase 2) of the action potential. Electrophysiological recordings of these cells show that Cav1.2 undergoes strong CDI [14–17]. Single-channel analyses of rat myocytes support a model in which Ca2+ entry through Cav1.2 channels shifts their gating to a mode with lower open probability [18, 19]. The fact that Cav1.2 CDI can be measured in single-channel recordings suggests that CDI requires local Ca2+ near the channel pore rather than global Ca2+ elevations due to the opening of multiple open channels.

It is now well-established that CDI involes calmodulin (CaM) binding to the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain (CT) the Cav1.2 α1 subunit (α11.2) [20]. CaM binds to a consensus site, the IQ-domain, in the proximal CT of α11.2. Ca2+ ions permeating the channel pore bind to the associated CaM, which produces a conformational change supporting CDI. The molecular details underlying CaM interactions with Cav channels have been covered in a several excellent reviews [20–22] and will not be a focus here. In whole-cell recordings, CaM inhibitors such as calmidazolium do not prevent CDI of Cav1.2 in cardiac myocytes [19], but such inhibitors may not antagonize CaM that is tightly associated with some effectors. Overexpression of CaM mutants that cannot bind Ca2+ not only inhibit CDI of Cav1.2 in ventricular myocytes, but also significantly prolongs cardiac action potentials [23]. Since excessively long action potentials can lead to cardiac arrhythmia, the ability of CDI to control action potential duration may protect against aberrant cardiac excitability.

CDI has also been characterized for L-type currents in neuronal and neuroendocrine cells that likely express both Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 [24]. However, the functional significance of Cav1 CDI in these cell-types is not entirely clear. Cav1 channels regulate Ca2+-dependent gene transcription which depends on CaM binding to the IQ-domain, but not on Cav1 CDI [25]. Under pathological conditions, such as in epilepsy, Cav1 CDI may be neuroprotective by preventing excitotoxic Ca2+ overloads in select neurons [26].

Cav1.3

While Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 may be expressed in many of the same cell-types in the brain and heart, Cav1.3 activates more rapidly and at negative voltages compared to Cav1.2 [27–30]. These properties allow its contribution to threshold depolarizations that promote spontaneous firing in the sinoatrial node, although Cav1.2 is also expressed in this tissue [31, 32]. In addition, Cav1.3 mediates ~90% of the whole-cell ICa in cochlear inner hair cells [33, 34]. Presynaptic Cav1.3 channels at the specialized “ribbon synapses” in inner hair cells conduct Ca2+ ions that trigger glutamate release at the first synapse in the auditory pathway [33]. The importance of Cav1.3 for hearing and cardiac pacemaking is underscored by the sinus bradycardia and deafness phenotypes in mice lacking Cav1.3 and humans with a loss-of-function mutation in the CACNA1D gene encoding α11.3 [35].

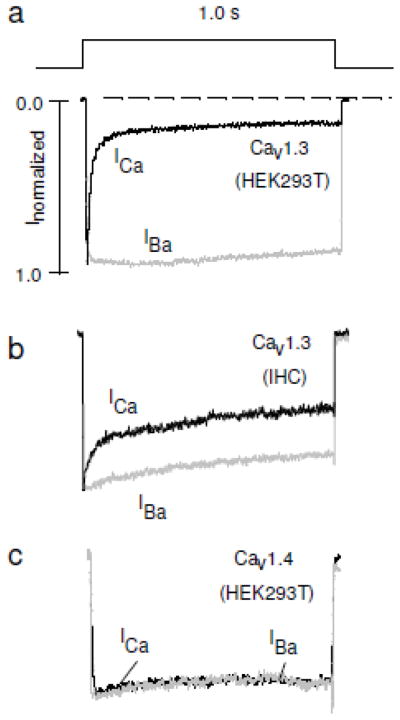

While Cav1.3 exhibits intense CDI when expressed heterologously, CDI is more limited in inner hair cells [28, 29, 34]. Whole-cell and perforated patch recordings from auditory hair cells in various species reveal ICa that inactivates only ~30–40% in 1 second while ICa in HEK293T cells transfected with Cav1.3 inactivates 80–90% within the same timeframe (Fig. 2a,b), although the extent of CDI in hair cells can vary with temperature and between species [36–38]. Differences in CDI of Cav1.3 between hair cells and other cell-types could be accounted for by alternative splicing of α11.3 which yields one variant lacking the IQ domain that exhibits little CDI. Since this variant is mainly expressed in outer hair cells, it is unlikely to account for the slow CDI in inner hair cells [39]. An alternate hypothesis is that Ca2+-binding proteins related to CaM oppose CDI of Cav1.3 in inner hair cells (See below).

Figure 2.

CDI of Cav1 channels. ICa (black) or IBa (grey) were evoked by 1-s depolarizing pulses in HEK293T cells transfected with Cav1.3 (a) or Cav1.4 (c) or in mouse inner hair cells (IHC), which express predominantly Cav1.3 (b).

Cav1.4

While the consensus site(s) for binding to CaM are relatively conserved between Cav1 channel subclasses, some intriguing differences in CDI have been noted. For example, Cav1.4, which is the primary Cav channel in retinal photoreceptors, undergoes little CDI [40, 41] (Fig. 2c). Similar to the role of Cav1.3 in inner hair cells, the ability of Cav1.4 to support sustained presynaptic L-type ICa helps maintain tonic glutamate release at ribbon synapses. CaM can bind to the Cav1.4 α1 subunit IQ domain, but this interaction may be disrupted by an inhibitory domain (ICDI: inhibitor of CDI) in the distal C-terminus [42, 43]. This domain is weakly conserved in other Cav1 channel subclasses, such that its transfer to the α11.2 or α11.3 nearly nullifies the normally strong CDI of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 [42, 43]. Multiple mutations in the CACNA1F gene encoding α11.4 cause congenital stationary night blindness type 2 [2], one of which (K1591X) causes premature truncation of α11.4 and deletion of the ICDI. As a consequence, Cav1.4 (K1591X) shows enhanced CDI [42], which could cause vision deficits due to a loss-of-function in photoreceptor transmission.

Cav1.1

In skeletal muscle, Cav1.1 channels are the “dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs)” that mediate excitation/contraction coupling. The voltage-sensing function of Cav1.1 is directly coupled to activation of Ca2+ release by ryanodine receptors in the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum, which initiates muscle contraction. Although Ca2+ conductance by Cav1.1 is not required for excitation/contraction coupling, Cav1.1 channels do mediate measurable L-type ICa in skeletal muscle cells [44]. Compared to Cav1.2, Cav1.1 undergoes modest CDI [45], which may be due to sequence differences in the IQ-domains that impair CaM binding and/or the affinity of bound CaM for Ca2+ [46–48]. In particular, Y1657 and K1662 in the rabbit cardiac α11.2 are replaced by H1532 and M1537 in the rabbit skeletal muscle α11.1. Substituting Y1657 and K1662 in α11.2 with the corresponding residues of α11.1 weaken CaM binding and eliminate CDI of Cav1.2 channels in transfected HEK293T cells [46]. However, additional residues that distinguish the IQ domain of α11.1 and α11.2, while not directly contacting CaM, alter its Ca2+ binding affinity. When bound to the IQ-domain of α11.2, the C- and N-terminal lobes of CaM bind Ca2+ with ~5-fold higher affinity than when bound to the α11.1 IQ-domain [47]. This latter result could explain why Cav1.1 CDI is weaker and more strongly inhibited by BAPTA than Cav1.2 CDI [45]. Sequence differences in the α11.1 IQ domain are probably not the only determinants of slow CDI in skeletal muscle. The expression of recombinant Cav1.2 channels in dysgenic myotubes, which lack functional Cav1.1 channels, results in L-type currents that lack CDI [12]. Thus, as for Cav1.3 in cochlear hair cells, factors that inhibit CDI of Cav1 channels may be endogenously expressed in skeletal muscle. The significance of slow CDI for Cav1.1 is unknown but may be important for preventing refractoriness of the voltage-sensing capabilities of Cav1.1 for excitation/contraction coupling [46].

Cav2 channels

Previous efforts to characterize CDI of Cav2 channels by heterologous expression did not reveal CDI [49] in part because of high concentrations of intracellular EGTA that are typically used for electrophysiological recordings of Cav1 channels. However, with a relatively low (0.5 mM) concentration of EGTA in intracellular recording solutions, CDI of Cav2.1 channels in transfected HEK293T cells is evident as significantly faster inactivation of ICa compared to IBa [50] (Fig. 1a). High concentrations (10 mM) of EGTA or BAPTA, which spare CDI of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3, completely block Cav2.1 CDI in transfected cells (Fig. 1c, [51, 52]). These results suggest that Cav2.1 CDI depends on global elevations in Ca2+ while Cav1.2 CDI depends on local Ca2+ elevations near the channel pore. Consistent with this hypothesis, unlike for Cav1.2 [18], CDI for Cav2.1 is not evident in single channel recordings [53]. In heterologous expression systems, the local Ca2+ sensitivity of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 CDI contrasts with the global Ca2+ sensitivity of CDI for all Cav2 channels [54].

Similar to Cav1.2 and Cav1.3, CDI for Cav2 channels involves CaM binding to an IQ-like domain in the Cav2 α1 C-terminal domain. For Cav2.1, an additional CaM-binding domain (CBD) C-terminal to the IQ-like domain is also involved. Mutations or deletions of both of these sites impact CDI [50–52, 55]. Besides this difference in CaM binding sites between Cav1.2 and Cav2.1, CDI for these channels relies on different Ca2+-binding lobes of CaM. This conclusion is based on electrophysiological experiments where CaM mutants unable to bind Ca2+ in the N- or C-lobes were co-transfected with Cav channels in HEK293T cells. These studies demonstrate a requirement for the CaM C-lobe for Cav1.2 CDI whereas the CaM N-lobe is needed for Cav2.1 CDI [52, 55, 56]. Structural analyses of CaM bound to α11.2, α12.1, α12.2, or α12.3 peptides containing the IQ domain indicate that distinctions in how CaM associates with key residues within and/or outside of the IQ domain may underlie the differences in Cav1.2 and Cav2 CDI [57–60].

A second CaM-binding determinant (NSCaTE) in the N-terminal domain of α11.2 and α11.3, that is not present in Cav2 α1 subunits, contributes to the difference in Ca2+ buffer sensitivity of CDI for Cav1 and Cav2 channels. Transfer of this region to the Cav2.2 α1 subunit (α12.2) allows for significant CDI in the presence of 10 mM BAPTA. The underlying mechanism may involve distinct interactions of the N- and C- terminal lobes of CaM with the Cav1 α1 NSCaTE and IQ domain, respectively [61].

Although intensely studied in heterologous expression systems, Cav2 CDI has been infrequently characterized for Cav2 channels in neurons. Ca2+ influx through Cav2 channels, particularly Cav2.1 and Cav2.2, initiates neurotransmitter release at many central synapses. Fluorometric analysis of Ca2+ influx in rat brain synaptosomes suggested CDI of P-type currents, which was suppressed by decreasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration [62]. CDI of presynaptic Ca2+ channels was also demonstrated in patch clamp recordings of presynaptic nerve terminals in the rat neurohypophysis [63] and for P-type currents at the Calyx of Held synapse in the rat auditory brainstem [64]. Because of the steep dependence of neurotransmitter release on presynaptic Ca2+ concentrations, Cav2 channel CDI could significantly inhibit neurotransmission. In support of this hypothesis, Cav2.1 CDI can cause short-term depression at the Calyx of Held and in transfected sympathetic neurons [64, 65].

Ca2+-dependent facilitation (CDF)

Facilitation is an enhanced form of channel opening that can be achieved through multiple mechanisms. CDF is a positive feedback regulation of further Ca2+ entry through Cav1 and Cav2 channels (CDF), which can significantly impact cell physiology in a variety of contexts. Although other forms of facilitation have been described for various Cav family members, CDF has mainly been described for native and heterologously expressed Cav1.2, Cav1.3, Cav2.1, and Cav3 channels.

Cav1.2

In cardiac ventricular myocytes, Cav1.2 CDF helps amplify intracellular Ca2+ signals coupled to contraction of the heart [66–68]. During a train of depolarizations, ICa progressively increases in amplitude, reaching a steady state by the fifth pulse [69]. Facilitation of ICa is Ca2+-dependent in that it can be induced by photolysis of caged-Ca2+ compounds [70] and is abolished by substitution of extracellular Ca2+ with Ba2+ or Sr2+ [69]. CDF can still be observed with 20 mM EGTA or 5 mM BAPTA in intracellular recording solutions, suggesting that Cav1.2 CDF depends on very local increases in Ca2+ near the channel [69].

Like CDI, CDF for Cav1.2 channels also depends on CaM, which activates CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). Two mechanisms have been proposed for the role of CaMKII in Cav1.2 CDF. In the first, CaMKII binds to the C-terminal domain of α11.2 near the IQ-domain, which may position the kinase for phosphorylating two nearby serine residues (S1512/S1570 in the mouse cardiac α11.2 [71, 72]. In transgenic mice in which these residues were mutated to alanine, L-type ICa shows slower recovery from inactivation and enhanced steady state inactivation, which is consistent with a loss of CDF. CDF was not completely abolished in ventricular myocytes from these mice, suggesting that other processes contribute to CDF (see below). In vivo telemetry in these mice revealed electrocardiograms with shorter QT intervals indicative of faster repolarization of cardiac action potentials. Since excessive CaMKII activity such as in heart failure causes QT prolongation and arrhythmia [73], the results suggest that Cav1.2 CDF, while normally beneficial for improving the force-frequency relationship of excitation/contraction coupling, may contribute to heart disease under pathological conditions.

A second route by which CaMKII enhances CDF is through interactions with the auxiliary Cav β2A subunit. CaMKII binds to and phosphorylates Cav β2A at threonine 498 (rat β2A), which enhances a mode of gating (mode 2) characterized by increased Cav1.2 channel open probability [74–76]. Overexpression of wild-type Cav β2A in ventricular myocytes causes Ca2+ overload and early after-depolarizations [77], which are premature depolarizations between cardiac action potentials that can cause arrhythmia. Moreover, rapid pacing, which would induce CDF, caused premature death of Cav β2A-overexpressing ventricular myocytes. By contrast, overexpression of Cav β2A with mutation of threonine 498 to alanine (or leucine 493 mutation that prevents CaMKII binding to Cav β2A) reduced Cav1.2 Ca2+ entry and early afterdepolarizations and also prevent Cav1.2 mode 2 gating [77]. These results confirm that Cav1.2 CDF can contribute to abnormal excitability that leads to cardiac arrhythmia and a key role for CaMKII/Cav β2A interactions in this process.

An important feature of CDF to consider in whole-cell recordings is the activation of CaMKII by repetitive Ca2+ spikes, which stimulates its autophosphorylation at threonine 286 and autonomous activity independent of Ca2+/CaM [78]. If L-type ICa is the Ca2+ source for CaMKII activation, autonomous activity should be more efficiently generated by short repetitive pulses rather than sustained depolarizations. In rat ventricular myocytes, CDF can be evoked with 150-ms pulses from −80 to 0 mV delivered at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. With this protocol, ICa increases in amplitude ~20% by the 4th pulse [76]. In theory, double-pulse voltage protocols such as those used to measure CDF of Cav2.1 (see below) could also be applied for analyses of Cav1.2 CDF. However, the voltage of the conditioning prepulse should not be so depolarized as to evoke voltage-dependent facilitation (VDF). Prepulses up to +160 mV have been used to demonstrate a role for CaMKII in Cav1.2 facilition [72]. However, little Ca2+ influx would be generated during such positive prepulses, due to the small driving force for Ca2+ influx near the reversal potential for Ca2+ in most electrophysiological recordings. Thus, the measured facilitation with such protocols is likely VDF rather than CDF [72].

While both CDF and CDI characterize Cav1.2 channels in cardiac myocytes, recombinant Cav1.2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes and HEK 293 cells show primarily CDI and very little CDF, even during repetitive stimuli [79, 80]. CDF for heterologously expressed Cav1.2 channels is only evident when CDI is inhibited, such as with α11.2 subunits containing I-A mutation in the IQ-domain [79]. Coexpression of the CaM-like protein, CaBP1, which also inhibits Cav1.2 CDI, also allows for Cav1.2 CDF that is independent of CaMKII [80, 81]. Thus, the presence of overt CDF that is not masked by CDI in cardiac myocytes may depend on cell-type specific differences in the processing of Cav1.2 channels or on cellular factors which are more abundant in cardiac cells than in heterologous expression systems.

Cav1.3

CaMKII is also implicated in CDF of Cav1.3 but through a mechanism distinct from that for Cav1.2. Cav1.3 channels do not exhibit CDF when expressed alone or with CaMKII in HEK293T cells. However, when cotransfected with CaMKII and densin-180, a CaMKII-interacting protein highly enriched at excitatory synapses in the brain [82, 83], Cav1.3 channels undergo CDF during repetitive depolarizations [84]. Densin-180 binds via its PDZ domain to the distal C-terminus of α11.3 and therefore may help scaffold CaMKII to the Cav1.3 channel complex. All three proteins coimmunoprecipitate from brain lysates, which suggests that densin 180 may permit CaMKII-dependent Cav1.3 CDF in neurons [84]. CaMKII activation in dendritic spines is mediated by Cav1 channels during stimulation protocols that produce long-term potentiation [85]. Thus, densin and CaMKII association with Cav1.3 may augment Ca2+ signals that trigger CaMKII activation and participation in long-term synaptic plasticity.

Cav2.1

At the Calyx of Held synapse, Cav2.1 channels initially undergo CDF and then CDI during high-frequency depolarizations, which can influence short-term facilitation and depression of the excitatory postsynaptic responses [64, 86–89]. This facilitation is Ca2+-dependent in that it is only seen for ICa and not IBa and reduced by high intracellular EGTA [86]. Similar biphasic CDF and CDI was also reported for Cav2.1 channels transfected into superior cervical ganglion neurons [65]. Here, CDF and CDI were also associated with short-term facilitation and depression of synaptic transmission [65]. The neurophysiological significance of short-term facilitation due to CDF is not entirely clear, but may ensure reliable transmission by offsetting depression [88].

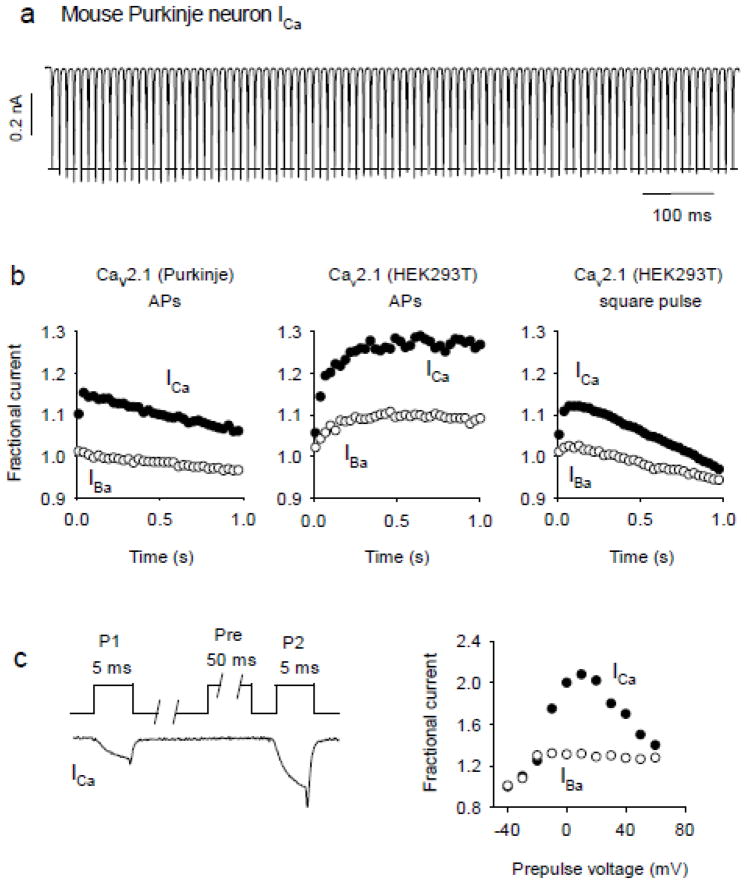

Cav2.1 channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons also undergo CDF as well as CDI during stimulation with action potential waveforms (Fig. 3a,b; [90–94]), but CDF tends to balance the effects of CDI in a way that maintains relatively constant ICa amplitudes [92]. In Purkinje neurons, P/Q-type ICa is strongly coupled to Ca2+-activated K+ channels that regulate Purkinje cell firing rates [95]. Fluctuations in ICa due to overt CDF or CDI may cause instabilities in firing that could prevent normal correlations of firing rate with synaptic activation [92]. The significance of CDF was also shown for Cav2.1 channels in presynaptic parallel fiber inputs to Purkinje neurons. Here, Cav2.1 channels bearing a mutation associated with familial hemiplegic migraine in humans (S218L) do not undergo CDF because they may be in a basally facilitated state. As a consequence, there is no short-term synaptic facilitation at this synapse [94]. Thus, the current data suggest that CDF plays a functionally more significant role for Cav2.1 in presynaptic terminals than in postsynaptic compartments of neurons.

Figure 3.

Characterization of CDF using repetitive and double pulse voltage-clamp protocols. (a) ICa is evoked in mouse cerebellar Purkinje neurons by a train of action potential (AP) waveforms at 100 Hz. CDF is evident as an initial increase in the amplitude of ICa above the baseline level (dashed line). (b) CDF is measured by plotting the peak amplitude of test currents normalized to the first in the train for ICa(filled circles) or IBa (open circles). Shown are results from AP trains in mouse cerebellar Purkinje neurons and Cav2.1-transfected HEK293T cells, and square test pulses (−80 mV to +10 mV, 100 Hz) for Cav2.1-transfected HEK293T cells. (c) Double-pulse protocol measures CDF of Cav2.1 in transfected HEK293T cells. Left, ICa was evoked by test currents evoked before (P1) or after (P2) a conditioning prepulse (Pre). The prepulse-induced current is not sampled in the representative current trace. The ratio of P2:P1 current amplitude (Fractional current) is plotted against prepulse voltage for ICa (filled circles) and IBa (open circles).

The mechanisms underlying CDF have been studied extensively for Cav2.1 channels in transfected HEK293T cells [52, 55]. Cav2.1 CDF depends on CaM binding to the IQ-domain of α12.1, with a reliance primarily on the C-lobe of CaM in contrast to the CaM N-lobe dependence of CDI [52, 55, 57, 59]. In transfected HEK293T cells, Cav2.1 CDF can be measured using 2–5-ms square pulses or action potential waveforms at a frequency of 100 Hz (Fig. 3b). CDF is plotted as the amplitude of each test current normalized to that for the first in the train. CDF can also be measured with double-pulse protocols with short (~20–50 ms) conditioning prepulses that evoke significant inward ICa (i.e., −80 mV to +10 mV). With this protocol, facilitation can be measured as the test current amplitude or charge integral normalized to a current in the absence of a prepulse. When plotted against prepulse voltage, facilitation of ICa, but not IBa, should be bell-shaped, reflecting its dependence on the amount of inward ICa during the prepulse (Fig. 3c).

In single-channel recordings, Cav2.1 CDF is associated with an enhanced open probability of ICa above that seen for IBa, rather than an acceleration of activation kinetics [53]. The detection of CDF but not CDI in single-channel recordings [53] suggests a different reliance on local vs. global Ca2+ signals for CDF and CDI, respectively. Consistent with this hypothesis, CDF, unlike CDI, is spared by 10 mM EGTA in whole-cell patch clamp recordings of transfected HEK293T cells [23, 55]. Analyses of CDF of transfected Cav2.1 channels would therefore benefit by high Ca2+ buffering conditions which would limit the competing effects of CDI. However, since the decay of CDF is significantly accelerated by high Ca2+ buffering in transfected cells [51], paired-pulse protocols should employ a relatively short interval between the conditioning prepulse and the test pulse for maximal CDF to be achieved.

Cav3

Cav3 channels are the major Cav channels in adrenal glomerulosa cells which secrete aldosterone in response to angiotensin II and physiological increases in K+ [96]. Angiotensin II stimulates Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, activation of CaMKII, and potentiation of Cav channel opening by K+-induced depolarization [97]. The facilitation involves CaMKII binding to and phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain linking domains 2 and 3 of α13.2 [98]. Phosphorylation of S1198 (human α13.2) negatively shifts voltage-dependent activation of Cav3.2 channels in HEK293 cells. This residue is not present in α13.1 and accounts for the absence of CaMKII regulation of Cav3.1 [98, 99]. Cell-attached single-channel recordings of T-type currents in adrenal glomerulosa cells show that raising the bath Ca2+ concentration enhances Cav3.2 channel open probability, which is accompanied by increased frequency, rather than longer duration, of channel openings [100]. In addition, Cav3.2 CDF is blocked by CaMKII inhibitors and mimicked by constitutively active CaMKII. Since CDF would cause Cav3.2 channels to open at more negative membrane potentials, CDF may help set the level of steady state Ca2+ influx and angiotensin II-stimulated aldosterone secretion. In heart failure, which is characterized by heightened activation of the renin-angiotensin system, Cav3.2 CDF may exacerbate the pathological consequences of excessive aldosterone secretion in heart failure, which include structural and functional changes in the heart and vasculature. Since Cav3.2 channels are highly expressed in the brain [101], CDF may also contribute to the roles of Cav3.2 in regulating firing patterns in multiple classes of neurons.

Factors that influence CDI and CDF in native cell-types

CDI and CDF, even for a given Cav subclass, can be highly variable between cell-types (Fig. 2a,b). Multiple factors can influence the extent to which Cav channels undergo CDI and CDF, which can complicate mechanistic inquiries as to their relative significance.

Alternative splicing of Cav α1

Post-translational splicing increases the functional diversity afforded by the 10 genes encoding Cavα1 subunits in the human, rat, and mouse genomes. Because of the large size of these genes (~50 exons), the number of splice variants possible for a single Cav α1 subunit may be greater than 1000 [102]. Like the α11.3 splice variant lacking the IQ domain in outer hair cells [39], all of the splice variations that have been found to impact CDI or CDF involve alterations in the C-terminal domain. For example, alternative splicing at exon 37 (human α12.1) produces two variants (EFa and EFb) with amino acid substitutions in an EF-hand like domain upstream from the CaM binding IQ-like domain and CBD [103]. The EFa but not the EFb variant exhibits CDF [104]. When combined with alternative splicing out of the final exon 47, EFb causes CDF that is blocked by high concentrations of BAPTA only in cells with large current density. Apparently, exclusion of exon 47 permits CDF in EFb containing Cav2.1 channels that is driven by global, rather than local, increases in Ca2+ [104]. How the absence of exon 47 when combined with EFb transforms the Ca2+-sensitivity of Cav2.1 CDF remains to be elucidated.

The distal C-terminal domain of α11.3 has also been shown to regulate CDI of Cav1.3. Alternative splicing of exons 42 and 42A produces α11.3 variants that extend >100 amino acids beyond the IQ-domain (exon 42) or are truncated just after the IQ-domain (exon 42A) [28, 105]. When compared in transfected HEK293T cells, the short exon 42A variant exhibits stronger CDI than the long exon 42 variant. FRET experiments suggested that the exon 42 sequence interfered with CaM binding to the proximal α11.3 C-terminal region including the IQ-domain [106]. Thus, this alternatively spliced exon plays a similar role in α11.3 as the distal CT in α11.4 [42, 43], except that the inhibitory effect on CDI is significantly less for Cav1.3 than for Cav1.4.

Cav β subunits

Because inactivation of Cav channels can occur by voltage- or Ca2+-dependent mechanisms (VDI or CDI), factors that minimize the former can enhance detection of the latter. For example, CDI is quite minimal in Cav2.1 channels that contain the Cavβ1b subunit due to the strong VDI that typifies this subunit composition [107]. Inclusion of the Cavβ2A, which produces Cav2.1 channels that show significantly weaker VDI than with Cavβ1b, results in robust CDI [51]. Considering the heterogeneous expression patterns of different Cavβ subunits [108], the magnitude of Cav2.1 CDI may vary between tissues and cell-types.

For Cav1.2 and Cav1.3, CDI is less dependent on the identity of the Cavβ subunit than for Cav2.1 channels. However, Cav1.2 CDF due to CaMKII may require Cavβ2 or Cavβ1 subunit. Biochemical studies indicate that autophosphorylated CaMKII stably associates with Cavβ2 and β1 but not β3 or β4 [74]. Although CaMKII can phosphorylate all four Cav β subunits to a similar extent, a conserved LXRXXS/T motif present in Cavβ2 and β1 but not β3 or β4 may be required for functionally relevant phosphorylation of Cavβ which ensures stability of the Cavβ/CaMKII complex [74]. To what extent Cavβ subunits influence the extent of Cav1.2 CDF awaits electrophysiological comparisons of CDF of Cav1.2 channels bearing distinct Cavβ subunits.

CaBPs

Due to their similarities with CaM, some neuron-specific CaBPs can substitute for CaM in binding to Cav channels, which can significantly alter CDF and CDI [109]. Like CaM, these CaBPs have four EF-hand Ca2+ binding domains, at least one of which is nonfunctional [110]. Other structural distinctions including N-terminal myristoylation and a longer central helical domain may confer some CaBPs with the ability to differentially modulate Cav channels compared to CaM [111]. For example, CaBP1 is colocalized to some extent with presynaptic Cav2.1 channels. Like CaM, CaBP1 binds to the CBD of α12.1, but does not support CDF and causes intense inactivation independent of Ca2+ [112]. Cav2.1 also can interact with other CaBPs, such as neuronal Ca2+ sensor-1 (NCS-1), which has inhibitory effects on P/Q-type current amplitude in Xenopus oocytes and adrenal chromaffin cells [113]. However, injection of purified NCS-1 protein into presynaptic nerve terminals at the Calyx of Held synapse promotes CDF of P/Q-type currents, and activity-dependent facilitation P/Q-type currents at this synapse can be prevented by injection of NCS-1-inhibitor peptides [114]. Therefore, the effects of NCS-1 on Cav2.1 may depend on the cellular and subcellular context in which they are coexpressed. A third CaBP that modulates Cav2.1 is visinin-like protein-2 (VILIP-2), which is highly expressed in the neocortex and hippocampus and undergoes Ca2+-dependent association with the plasma membrane in neurons and other cell-types [115]. When cotransfected with Cav2.1 in mammalian cells, VILIP-2 does not affect CDF, but inhibits CDI [116]. These effects of VILIP-2 may involve displacement of CaM from the CBD, although both CBD and IQ-like domain of α12.1 are required for the association of VILIP-2 with the channel [116]. How VILIP-2 and CaBP1 can have such opposing effects on Cav2.1 function is not entirely clear, but may involve structural distinctions between the two CaBPs and/or how they interact with Cav2.1 [117]. The remarkably divergent actions of CaBPs on Cav2.1 may increase the range of presynaptic P/Q-type Ca2+ signals, thus contributing to heterogeneous forms of short-term plasticity at different synapses.

Cav1 channels are also differentially regulated by CaBPs. Unlike its inhibitory effects on Cav2.1, CaBP1 prolongs Cav1.2 Ca2+ currents and completely abolishes CDI [80, 118]. Structural analyses indicate that the opposing actions of CaM and CaBP1 on Cav1.2 may depend on differences in how the two interact with the IQ-domain [81]. In addition, CaBP1 binds to a site in the N-terminal domain of the α11.2, which can affect both CDI and VDI [118, 119]. Interestingly, a CaBP1 variant, caldendrin, causes more modest suppression of Cav1.2 CDI than CaBP1 through interactions solely with the IQ-domain and not the N-terminal site in α11.2 [120]. CaBP1 and caldendrin associate and colocalize with Cav1.2 in somatodendritic domains of neurons [80, 120], and so may help fine-tune and boost postsynaptic Cav2.1 Ca2+ signals that regulate gene transcription and neuronal excitability.

CaBP1 is highly expressed in inner hair cells where Cav1.3 channels exhibit anomalously slow CDI at room temperature compared to in transfected cells at room temperature [29, 34, 121, 122]. Consistent with a role for CaBP1 in the mechanism, coexpression of CaBP1 with Cav1.3 in HEK293T cells strongly inhibits CDI [121, 122]. In addition to CaBP1, CaBP2, 4, and 5 are also expressed in inner hair cells. However, when Cav1.3 is cotransfected with each of these CaBPs in HEK293T cells, the effects of CaBP1 on slowing CDI and also VDI most closely reproduce the slowly inactivating properties of Cav1.3 in inner hair cells. In addition, genetic inactivation of CaBP4 in mice has only a minor effect on CDI and no impact on hearing [121]. Confirmation of the role of CaBP1 in CDI suppression awaits similar analyses in inner hair cells from CaBP1 null mice.

In addition to these CaM-like CaBPs, Ca2+ binding proteins such as parvalbumin (PV) and calbindin D-28k (CB), which serve more as Ca2+ buffers [123], also regulate Cav CDI. PV and CB are highly expressed in Purkinje neurons where ICa is largely mediated by Cav2.1 [124]. Since Cav2.1 CDI is sensitive to Ca2+ buffers that dampen global Ca2+ elevations [51], one would expect that PV and CB might similarly naturally suppress CDI. This hypothesis was partially supported in transfected HEK293T cells [125]. If PV and CB inhibited CDI in Purkinje neurons, then CDI should be increased in neurons from mice with genetic inactivation of the genes encoding PV and CB. However, Purkinje neurons isolated from mice lacking PV and CB showed a decrease in Cavβ2A expression and consistently, increased VDI but not CDI compared to in wild-type neurons [90]. This alteration may have been a compensatory response to prevent excessive Cav2.1 Ca2+ influx in neurons lacking the Ca2+ buffering capacity of PV and CB. Thus, whether Ca2+ buffering proteins limit CDI of neuronal Cav2.1 channels remains to be proven.

Despite evidence that Cav1 CDI in transfected HEK293T cells is relatively insensitive to Ca2+ buffers [54, 61], CDI of Cav1 channels in thalamocortical neurons was shown to be inhibited by inclusion of PV and CB in intracellular whole-cell recording solutions in isolated thalamocortical neurons [126]. Further evidence for a role for Ca2+ buffering proteins in regulating Cav CDI comes from recordings of surviving hippocampal granule cells isolated from the dentate gyrus of patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. These cells have reduced levels of CB, which correlates with increased CDI of Cav1 L-type currents [26]. Unlike for Cav1 channels in transfected cells, Cav1 CDI in these surviving granule cells is inhibited by high intracellular concentrations of BAPTA or EGTA [127]. Why Cav1 CDI is sensitive to Ca2+ buffers in these neurons but not in HEK293T cells is unclear, but could be related to the presence of Cav1 α1 splice variants that may lack the NSCaTE [61]. Alternatively, CaBPs with distinct Ca2+ binding affinities compared to CaM might compete with CaM for binding to the Cav1 IQ domain or NSCaTE in neurons. Regardless of the mechanism, the ability of PV and/or CB to suppress Cav1 CDI in neurons may be necessary for supporting Ca2+ signals of sufficient duration to activate signaling pathways underlying activity-dependent synaptic plasticity [128]. Moreover, pathological decreases in neuronal Ca2+ buffering, such as in temporal lobe epilepsy [26], may be neuroprotective in increasing Cav1 CDI and reducing excitotoxic Ca2+ overloads.

Other cellular factors

Cells such as myocytes and neurons have complex subcellular features that could also significantly impact the extent to which Cav channels undergo CDI and CDF. This seems to be particularly true in skeletal and cardiac muscle cells in which Cav1 channels are tightly clustered at junctional membranes in association with intracellular ryanodine receptors (RYRs) in the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum. In cardiac myocytes, Ca2+ influx through Cav1.2 channels enhances Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release through activation of RYRs. Due to the tight spatial coupling of RYRs and Cav1.2 in junctional membranes, Cav1.2 CDI is enhanced by RYR-mediated Ca2+ signals [129]. Such functional coupling between RYRs and Cav1.2 may also occur in neurons [130], since blockade of RYRs in thalamocortical neurons decreased Cav1 CDI [131].

The cytoskeleton has also been implicated as a determinant of CDI in neurons [132, 133]. It is hypothesized that Ca2+ influx through Cav channels destabilizes cytoskeletal elements, which promotes CDI. In support of this hypothesis, pharmacological stabilization of microfilaments and microtubules reduce Cav CDI in neurons [127, 133]. How cytoskeletal dynamics participate in CDI regulation is unclear, but may involve Cav α1 interactions with Cav β subunits and/or cytoskeleton-associated proteins [24].

Summary and remaining questions

Electrophysiological analyses have led to detailed insights into the mechanisms and prevalence of CDI and CDF as Cav channel regulatory mechanisms. All Cav channel family members undergo some form of Ca2+-dependent feedback that relies on CaM or a related Ca2+ binding protein. Tremendous progress has been made in characterizing the role of CaM in CDI and CDF of Cav1 and Cav2 channels at the molecular and atomic scales. Yet, numerous ambiguities remain. First, what determines the variability in CaM-dependent CDI/CDF in native cell types? At one extreme, Cav1 channels in photoreceptors and inner hair cells have mechanisms that prevent CDI, to allow for sustained Ca2+-dependent exocytosis required for sensory transmission. By contrast, intense CaM-dependent CDI of Cav1 channels in cardiac myocytes is necessary for curtailing cardiac action potentials and maintaining cardiac rhythmicity. Molecular and biochemical analyses of Cav splice variation and Cav/protein interactions may reveal mechanisms underlying the heterogeneous presentations of Cav CDI/CDF in a variety of cell-types.

Second, how does CDI/CDF control cellular excitability and other Ca2+ signaling events? Due to the depolarizing influence of Cav currents, CDI could directly inhibit neuronal excitability. However, due to the tight coupling of Cav channels with Ca2+-dependent K+ (KCa) channels, CDF could also inhibit excitability through stronger activation of KCa channels. Detailed consideration of CDI/CDF within computational models of cellular and network excitability is a necessary first step towards understanding the broader impact of these forms of Cav channel modulation in defined physiological contexts.

Highlights.

Electrophysiological analysis have revealed detailed mechanisms of Cav channel modulation.

Cav channels undergo CDI/CDF that relies on Ca2+ binding proteins like calmodulin.

The heterogeneity of CDI/CDF in various cell-types remains largely unexplored.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (DC009433, HL087120 to AL and T32007121 to CC). The authors would like to thank Akira Inagaki and other lab members for contribution of data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Striessnig J, Bolz HJ, Koschak A. Channelopathies in Cav1.1, Cav1.3, and Cav1.4 voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:361–374. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0800-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietrobon D. Calcium channels and channelopathies of the central nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 2002;25:31–50. doi: 10.1385/MN:25:1:031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidaud I, Lory P. Hallmarks of the channelopathies associated with L-type calcium channels: A focus on the Timothy mutations in Ca(v)1.2 channels. Biochimie. 2011;93:2080–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brehm P, Eckert R. Calcium entry leads to inactivation of calcium channel in Paramecium. Science. 1978;202:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.103199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brehm P, Dunlap K, Eckert R. Calcium-dependent repolarization in Paramecium. J Physiol. 1978;274:639–654. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naitoh Y. Ionic control of the reversal response of cilia in Paramecium caudatum. A calcium hypothesis. J Gen Physiol. 1968;51:85–103. doi: 10.1085/jgp.51.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckert R, Chad JE. Inactivation of Ca channels. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1984;44:215–267. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(84)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byerly L, Hagiwara S. Calcium channel diversity. In: Grinnell AD, Armstrong D, Jackson M, editors. Calcium and Ion Channel Modulation. Plenum Press, Inc; New York: 1990. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckert R, Tillotson DL. Calcium-mediated inactivation of the calcium conductance in caesium-loaded giant neurones of Aplysia californica. J Physiol. 1981;314:265–280. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tillotson D. Inactivation of Ca conductance dependent on entry of Ca ions in molluscan neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:1497–1500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikami A, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Niidome T, Mori Y, Takeshima H, Narumiya S, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression of the cardiac dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel. Nature. 1989;340:230–233. doi: 10.1038/340230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seisenberger C, Specht V, Welling A, Platzer J, Pfeifer A, Kuhbandner S, Striessnig J, Klugbauer N, Feil R, Hofmann F. Functional embryonic cardiomyocytes after disruption of the L-type alpha1C (Cav1.2) calcium channel gene in the mouse. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39193–39199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kass RS, Sanguinetti MC. Inactivation of calcium channel current in the calf cardiac Purkinje fiber. Evidence for voltage- and calcium-mediated mechanisms. J Gen Physiol. 1984;84:705–726. doi: 10.1085/jgp.84.5.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mentrard D, Vassort G, Fischmeister R. Calcium-mediated inactivation of the calcium conductance in cesium-loaded frog heart cells. J Gen Physiol. 1984;83:105–131. doi: 10.1085/jgp.83.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KS, Marban E, Tsien RW. Inactivation of calcium channels in mammalian heart cells: joint dependence on membrane potential and intracellular calcium. J Physiol. 1985;364:395–411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadley RW, Hume JR. An intrinsic potential-dependent inactivation mechanism associated with calcium channels in guinea-pig myocytes. J Physiol. 1987;389:205–222. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yue DT, Backx PH, Imredy JP. Calcium-sensitive inactivation in the gating of single calcium channels. Science. 1990;250:1735–1738. doi: 10.1126/science.2176745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imredy JP, Yue DT. Mechanism of Ca2+-sensitive inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 1994;12:1301–1318. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halling DB, Aracena-Parks P, Hamilton SL. Regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by calmodulin. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:er1. doi: 10.1126/stke.3182006er1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minor DL, Jr, Findeisen F. Progress in the structural understanding of voltage-gated calcium channel (CaV) function and modulation. Channels. 2010;4:459–474. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.6.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catterall WA, Few AP. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alseikhan BA, DeMaria CD, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17185–17190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262372999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budde T, Meuth S, Pape HC. Calcium-dependent inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:873–883. doi: 10.1038/nrn959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolmetsch RE, Pajvani U, Fife K, Spotts JM, Greenberg ME. Signaling to the nucleus by an L-type calcium channel-calmodulin complex through the MAP kinase pathway. Science. 2001;294:333–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1063395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagerl UV, Mody I, Jeub M, Lie AA, Elger CE, Beck H. Surviving granule cells of the sclerotic human hippocampus have reduced Ca(2+) influx because of a loss of calbindin-D(28k) in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1831–1836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01831.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helton TD, Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal L-type calcium channels open quickly and are inhibited slowly. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10247–10251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1089-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal Cav1.3 α1 L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5944–5951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05944.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koschak A, Reimer D, Huber I, Grabner M, Glossmann H, Engel J, Striessnig J. α1D (Cav1.3) subunits can form L-type Ca2+ channels activating at negative voltages. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22100–22106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholze A, Plant TD, Dolphin AC, Nurnberg B. Functional expression and characterization of a voltage-gated CaV1.3 (α1D) calcium channel subunit from an insulin-secreting cell line. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1211–1221. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Z, He Y, Tuteja D, Xu D, Timofeyev V, Zhang Q, Glatter KA, Xu Y, Shin HS, Low R, Chiamvimonvat N. Functional roles of Cav1.3(alpha1D) calcium channels in atria: insights gained from gene-targeted null mutant mice. Circulation. 2005;112:1936–1944. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangoni ME, Couette B, Bourinet E, Platzer J, Reimer D, Striessnig J, Nargeot J. Functional role of L-type Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels in cardiac pacemaker activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5543–5548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0935295100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brandt A, Striessnig J, Moser T. CaV1.3 channels are essential for development and presynaptic activity of cochlear inner hair cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10832–10840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10832.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platzer J, Engel J, Schrott-Fischer A, Stephan K, Bova S, Chen H, Zheng H, Striessnig J. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baig SM, Koschak A, Lieb A, Gebhart M, Dafinger C, Nurnberg G, Ali A, Ahmad I, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Brandt N, Engel J, Mangoni ME, Farooq M, Khan HU, Nurnberg P, Striessnig J, Bolz HJ. Loss of Ca(v)1.3 (CACNA1D) function in a human channelopathy with bradycardia and congenital deafness. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nn.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grant L, Fuchs P. Calcium- and calmodulin-dependent inactivation of calcium channels in inner hair cells of the rat cochlea. Journal of neurophysiology. 2008;99:2183–2193. doi: 10.1152/jn.01174.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnee ME, Ricci AJ. Biophysical and pharmacological characterization of voltage-gated calcium currents in turtle auditory hair cells. J Physiol. 2003;549:697–717. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.037481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcotti W, Johnson SL, Rusch A, Kros CJ. Sodium and calcium currents shape action potentials in immature mouse inner hair cells. J Physiol. 2003;552:743–761. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen Y, Yu D, Hiel H, Liao P, Yue DT, Fuchs PA, Soong TW. Alternative splicing of the Cav1.3 channel IQ domain, a molecular switch for Ca2+-dependent inactivation within auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10690–10699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2093-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baumann L, Gerstner A, Zong X, Biel M, Wahl-Schott C. Functional characterization of the L-type Ca2+ channel Cav1.4alpha1 from mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:708–713. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McRory JE, Hamid J, Doering CJ, Garcia E, Parker R, Hamming K, Chen L, Hildebrand M, Beedle AM, Feldcamp L, Zamponi GW, Snutch TP. The CACNA1F gene encodes an L-type calcium channel with unique biophysical properties and tissue distribution. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1707–1718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4846-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh A, Hamedinger D, Hoda JC, Gebhart M, Koschak A, Romanin C, Striessnig J. C-terminal modulator controls Ca2+-dependent gating of Ca(v)1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1108–1116. doi: 10.1038/nn1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wahl-Schott C, Baumann L, Cuny H, Eckert C, Griessmeier K, Biel M. Switching off calcium-dependent inactivation in L-type calcium channels by an autoinhibitory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15657–15662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604621103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bannister RA, Pessah IN, Beam KG. The skeletal L-type Ca(2+) current is a major contributor to excitation-coupled Ca(2+) entry. The Journal of general physiology. 2009;133:79–91. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stroffekova K. Ca2+/CaM-dependent inactivation of the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel (Cav1.1) Pflugers Archiv: European journal of physiology. 2008;455:873–884. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohrtman J, Ritter B, Polster A, Beam KG, Papadopoulos S. Sequence differences in the IQ motifs of CaV1.1 and CaV1.2 strongly impact calmodulin binding and calcium-dependent inactivation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:29301–29311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805152200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halling DB, Georgiou DK, Black DJ, Yang G, Fallon JL, Quiocho FA, Pedersen SE, Hamilton SL. Determinants in CaV1 channels that regulate the Ca2+ sensitivity of bound calmodulin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:20041–20051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pate P, Mochca-Morales J, Wu Y, Zhang JZ, Rodney GG, Serysheva II, Williams BY, Anderson ME, Hamilton SL. Determinants for calmodulin binding on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39786–39792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cens T, Mangoni ME, Nargeot J, Charnet P. Modulation of the α1A Ca2+ channel by β subunits at physiological Ca2+ concentration. FEBS Lett. 1996;391:232–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00704-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee A, Wong ST, Gallagher D, Li B, Storm DR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin binds to and modulates P/Q-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:155–159. doi: 10.1038/20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee A, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation and inactivation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6830–6838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06830.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeMaria CD, Soong T, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS, Yue DT. Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2001;411:484–489. doi: 10.1038/35078091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaudhuri D, Issa JB, Yue DT. Elementary mechanisms producing facilitation of Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) channels. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:385–401. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang H, DeMaria CD, Erickson MG, Mori MX, Alseikhan B, Yue DT. Unified mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation across the Ca2+ channel family. Neuron. 2003;39:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee A, Zhou H, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent regulation of Cav2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16059–16064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+ -dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999;22:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim EY, Rumpf CH, Fujiwara Y, Cooley ES, Van Petegem F, Minor DL., Jr Structures of CaV2 Ca2+/CaM-IQ domain complexes reveal binding modes that underlie calcium-dependent inactivation and facilitation. Structure. 2008;16:1455–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Petegem F, Chatelain FC, Minor DLJ. Insights into voltage-gated calcium channel regulation from the structure of the CaV1.2 IQ domain-Ca2+/calmodulin complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mori MX, Vander Kooi CW, Leahy DJ, Yue DT. Crystal Structure of the Cav2 IQ Domain in Complex with Ca2+/Calmodulin: High-Resolution Mechanistic Implications for Channel Regulation by Ca2+ Structure. 2008;16:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fallon JL, Halling DB, Hamilton SL, Quiocho FA. Structure of calmodulin bound to the hydrophobic IQ domain of the cardiac Cav1.2 calcium channel. Structure. 2005;13:1881–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dick IE, Tadross MR, Liang H, Tay LH, Yang W, Yue DT. A modular switch for spatial Ca2+ selectivity in the calmodulin regulation of CaV channels. Nature. 2008;451:830–834. doi: 10.1038/nature06529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tareilus E, Schoch J, Breer H. Ca2+-dependent inactivation of P-type calcium channels in nerve terminals. J Neurochem. 1994;62:2283–2291. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62062283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Branchaw JL, Banks MI, Jackson MB. Ca2+- and voltage-dependent inactivation of Ca2+ channels in nerve terminals of the neurohypophysis. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5772–5781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05772.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Cuttle MF, Takahashi T. Inactivation of presynaptic calcium current contributes to synaptic depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron. 1998;20:797–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mochida S, Few AP, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Regulation of presynaptic Ca(V)2.1 channels by Ca2+ sensor proteins mediates short-term synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;57:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marban E, Tsien RW. Enhancement of calcium current during digitalis inotropy in mammalian heart: positive feed-back regulation by intracellular calcium? J Physiol. 1982;329:589–614. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mitra R, Morad M. Two types of calcium channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5340–5344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCarron JG, McGeown JG, Reardon S, Ikebe M, Fay FS, Walsh JJV. Calcium-dependent enhancement of calcium current in smooth muscle by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nature. 1992;357:74–77. doi: 10.1038/357074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zygmunt AC, Maylie J. Stimulation-dependent facilitation of the high threshold calcium current in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1990;428:653–671. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gurney AM, Charnet P, Pye JM, Nargeot J. Augmentation of cardiac calcium current by flash photolysis of intracellular caged-Ca2+ molecules. Nature. 1989;341:65–68. doi: 10.1038/341065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hudmon A, Schulman H, Kim J, Maltez JM, Tsien RW, Pitt GS. CaMKII tethers to L-type Ca2+ channels, establishing a local and dedicated integrator of Ca2+ signals for facilitation. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:537–547. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee TS, Karl R, Moosmang S, Lenhardt P, Klugbauer N, Hofmann F, Kleppisch T, Welling A. Calmodulin kinase II is involved in voltage-dependent facilitation of the L-type Cav1.2 calcium channel: Identification of the phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25560–25567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anderson ME, Brown JH, Bers DM. CaMKII in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;51:468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abiria SA, Colbran RJ. CaMKII associates with Ca(V)1.2 L-type calcium channels via selected beta subunits to enhance regulatory phosphorylation. J Neurochem. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grueter CE, Abiria SA, Dzhura I, Wu Y, Ham AJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME, Colbran RJ. L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation mediated by phosphorylation of the β subunit by CaMKII. Mol Cell. 2006;23:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grueter CE, Abiria SA, Wu Y, Anderson ME, Colbran RJ. Differential Regulated Interactions of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II with Isoforms of Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel beta Subunits. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1760–1767. doi: 10.1021/bi701755q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koval OM, Guan X, Wu Y, Joiner ML, Gao Z, Chen B, Grumbach IM, Luczak ED, Colbran RJ, Song LS, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. CaV1.2 beta-subunit coordinates CaMKII-triggered cardiomyocyte death and afterdepolarizations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:4996–5000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913760107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science. 1998;279:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zühlke RD, Pitt GS, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Calmodulin supports both inactivation and facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:159–162. doi: 10.1038/20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou H, Kim SA, Kirk EA, Tippens AL, Sun H, Haeseleer F, Lee A. Ca2+-binding protein-1 facilitates and forms a postsynaptic complex with Cav1.2 (L-type) Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4698–4708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5523-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Findeisen F, Minor DL., Jr Structural basis for the differential effects of CaBP1 and calmodulin on Ca(V)1.2 calcium-dependent inactivation. Structure. 2010;18:1617–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Strack S, Robison AJ, Bass MA, Colbran RJ. Association of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II with developmentally regulated splice variants of the postsynaptic density protein densin-180. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25061–25064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walikonis RS, Oguni A, Khorosheva EM, Jeng CJ, Asuncion FJ, Kennedy MB. Densin-180 forms a ternary complex with the α-subunit of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and α-actinin. J Neurosci. 2001;21:423–433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00423.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jenkins MA, Christel CJ, Jiao Y, Abiria S, Kim KY, Usachev YM, Obermair GJ, Colbran RJ, Lee A. Ca2+-dependent facilitation of Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels by densin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:5125–5135. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4367-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee SJ, Escobedo-Lozoya Y, Szatmari EM, Yasuda R. Activation of CaMKII in single dendritic spines during long-term potentiation. Nature. 2009;458:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nature07842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cuttle MF, Tsujimoto T, Forsythe ID, Takahashi T. Facilitation of the presynaptic calcium current at an auditory synapse in rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;512:723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.723bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Borst JG, Sakmann B. Facilitation of presynaptic calcium currents in the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;513:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.149by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muller M, Felmy F, Schneggenburger R. A limited contribution of Ca2+ current facilitation to paired-pulse facilitation of transmitter release at the rat calyx of Held. The Journal of physiology. 2008;586:5503–5520. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Inchauspe CG, Martini FJ, Forsythe ID, Uchitel OD. Functional compensation of P/Q by N-type channels blocks short-term plasticity at the calyx of held presynaptic terminal. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:10379–10383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2104-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kreiner L, Christel CJ, Benveniste M, Schwaller B, Lee A. Compensatory regulation of Cav2.1 Ca2+ channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons lacking parvalbumin and calbindin D-28k. Journal of neurophysiology. 2010;103:371–381. doi: 10.1152/jn.00635.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chaudhuri D, Alseikhan BA, Chang SY, Soong TW, Yue DT. Developmental activation of calmodulin-dependent facilitation of cerebellar P-type Ca2+ current. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8282–8294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2253-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Benton MD, Raman IM. Stabilization of Ca current in Purkinje neurons during high-frequency firing by a balance of Ca-dependent facilitation and inactivation. Channels. 2009;3:393–401. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.6.9838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Richards KS, Swensen AM, Lipscombe D, Bommert K. Novel CaV2.1 clone replicates many properties of Purkinje cell CaV2.1 current. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2950–2961. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Adams PJ, Rungta RL, Garcia E, van den Maagdenberg AM, MacVicar BA, Snutch TP. Contribution of calcium-dependent facilitation to synaptic plasticity revealed by migraine mutations in the P/Q-type calcium channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:18694–18699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009500107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raman IM, Bean BP. Ionic currents underlying spontaneous action potentials in isolated cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1664–1674. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01663.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rossier MF, Burnay MM, Vallotton MB, Capponi AM. Distinct functions of T- and L-type calcium channels during activation of bovine adrenal glomerulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4817–4826. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen XL, Bayliss DA, Fern RJ, Barrett PQ. A role for T-type Ca2+ channels in the synergistic control of aldosterone production by ANG II and K+ The American journal of physiology. 1999;276:F674–683. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.5.F674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Welsby PJ, Wang H, Wolfe JT, Colbran RJ, Johnson ML, Barrett PQ. A mechanism for the direct regulation of T-type calcium channels by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:10116–10121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-10116.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yao J, Davies LA, Howard JD, Adney SK, Welsby PJ, Howell N, Carey RM, Colbran RJ, Barrett PQ. Molecular basis for the modulation of native T-type Ca2+ channels in vivo by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2403–2412. doi: 10.1172/JCI27918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barrett PQ, Lu HK, Colbran R, Czernik A, Pancrazio JJ. Stimulation of unitary T-type Ca(2+) channel currents by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1694–1703. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Talley EM, Cribbs LL, Lee JH, Daud A, Perez-Reyes E, Bayliss DA. Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19:1895–1911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gray AC, Raingo J, Lipscombe D. Neuronal calcium channels: splicing for optimal performance. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Soong TW, DeMaria CD, Alvania RS, Zweifel LS, Liang MC, Mittman S, Agnew WS, Yue DT. Systematic identification of splice variants in human P/Q-type channel α12.1 subunits: implications for current density and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10142–10152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chaudhuri D, Chang SY, DeMaria CD, Alvania RS, Soong TW, Yue DT. Alternative splicing as a molecular switch for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6334–6342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Safa P, Boulter J, Hales TG. Functional properties of Cav1.3 (alpha1D) L-type Ca2+ channel splice variants expressed by rat brain and neuroendocrine GH3 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38727–38737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Singh A, Gebhart M, Fritsch R, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Poggiani C, Hoda JC, Engel J, Romanin C, Striessnig J, Koschak A. Modulation of voltage- and Ca2+-dependent gating of CaV1.3 L-type calcium channels by alternative splicing of a C-terminal regulatory domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20733–20744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802254200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stea A, Tomlinson WJ, Soong TW, Bourinet E, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP. The localization and functional properties of a rat brain α1A calcium channel reflect similarities to neuronal Q- and P-type channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:10576–10580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Buraei Z, Yang J. The ss subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Calin-Jageman I, Lee A. Cav1 L-type Ca2+ channel signaling complexes in neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;105:573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Haeseleer F, Imanishi Y, Sokal I, Filipek S, Palczewski K. Calcium-binding proteins: intracellular sensors from the calmodulin superfamily. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:615–623. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Haeseleer F, Sokal I, Verlinde CL, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pronin AN, Benovic JL, Fariss RN, Palczewski K. Five members of a novel Ca2+-binding protein (CABP) subfamily with similarity to calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1247–1260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee A, Westenbroek RE, Haeseleer F, Palczewski K, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Differential modulation of Cav2.1 channels by calmodulin and Ca2+-binding protein 1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:210–217. doi: 10.1038/nn805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Weiss JL, Hui H, Burgoyne RD. Neuronal calcium sensor-1 regulation of calcium channels, secretion, and neuronal outgrowth. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:1283–1292. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9588-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tsujimoto T, Jeromin A, Saitoh N, Roder JC, Takahashi T. Neuronal calcium sensor 1 and activity-dependent facilitation of p/q-type calcium currents at presynaptic nerve terminals. Science. 2002;295:2276–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.1068278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Braunewell KH, Klein-Szanto AJ. Visinin-like proteins (VSNLs): interaction partners and emerging functions in signal transduction of a subfamily of neuronal Ca2+-sensor proteins. Cell and tissue research. 2009;335:301–316. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0716-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lautermilch NJ, Few AP, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Modulation of CaV2.1 channels by the neuronal calcium-binding protein visinin-like protein-2. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7062–7070. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0447-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Few AP, Lautermilch NJ, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Differential regulation of CaV2.1 channels by calcium-binding protein 1 and visinin-like protein-2 requires N-terminal myristoylation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7071–7080. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0452-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhou H, Yu K, McCoy KL, Lee A. Molecular mechanism for divergent regulation of Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels by calmodulin and Ca2+-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29612–29619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Oz S, Tsemakhovich V, Christel CJ, Lee A, Dascal N. CaBP1 regulates voltage-dependent inactivation and activation of Ca(V)1.2 (L-type) calcium channels. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:13945–13953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tippens AL, Lee A. Caldendrin: a neuron-specific modulator of Cav1.2 (L-type) Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8464–8473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cui G, Meyer AC, Calin-Jageman I, Neef J, Haeseleer F, Moser T, Lee A. Ca2+-binding proteins tune Ca2+-feedback to Cav1.3 channels in auditory hair cells. J Physiol. 2007;585:791–803. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yang PS, Alseikhan BA, Hiel H, Grant L, Mori MX, Yang W, Fuchs PA, Yue DT. Switching of Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Cav1.3 channels by calcium binding proteins of auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10677–10689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3236-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]