Abstract

Objective

To evaluate sexual function in midlife women using SSRIs for vasomotor symptoms. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) effectively treat vasomotor symptoms, but adversely affect sexual function in depressed populations. Information on sexual function in nondepressed midlife women using SSRIs for vasomotor symptoms is lacking - any treatments that might impair function are of concern.

Methods

This was a randomized controlled trial comparing 8 weeks of escitalopram compared to placebo in women ages 40-62 years with 28 or more bothersome vasomotor symptoms per week. Change in Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) composite score (ranges from 2 [not sexually active, no desire] to 36) and 6 sexual domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain); and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS), a single-question of sexually-related personal distress, were compared between groups.

Results

Among all women, median composite baseline FSFI score was 18.1 (interquartile range [IQR] 2.4, 26.5, n=200) and among sexually active women was 22.8 (IQR 17.4, 27.0, n=75) in the escitalopram group and 23.6 (IQR 14.9, 31.0, n=70) in the placebo group.

Treatment with escitalopram did not affect composite Female Sexual Function Index score at follow-up compared to placebo (p=0.18 all women; p=0.47 sexually active at baseline). Composite mean Female Sexual Function Index change from baseline to week 8 was 0.1 (95% CI -1.5, 1.7) for escitalopram and 2.0 (95% CI 0.2, 3.8) for placebo. The Female Sexual Distress Scale results did not differ between groups (p=0.73), nor did adverse reports of sexual function. At week 8, among those women sexually active at baseline, there was a small difference between groups in Female Sexual Function Index domain mean score change in lubrication (p=0.02) and a marginal nonsignificant difference in orgasm (p=0.07).

Conclusions

Escitalopram, when used in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms, did not worsen overall sexual function among nondepressed midlife women.

Introduction

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are used to treat vasomotor symptoms (VMS) in women and men, the majority of whom are not depressed. SSRI therapy for menopause is particularly common since the Women's Health Initiative showed increased risk of breast cancer, stroke, myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolism with conventional hormonal therapies (1-3). We previously reported a modest benefit of the SSRI, escitalopram, for non-depressed midlife women with VMS (4). Escitalopram was well-tolerated and promoted VMS improvement for the majority of study participants randomly assigned to the SSRI.

Notably, however, sexual dysfunction is a commonly reported adverse effect of SSRIs among men and women with depression (5;6). Sexual dysfunction is also reported among premenopausal women taking SSRIs for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) (7). Chief complaints most common among depressed men receiving SSRI or SNRI therapy are erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, anorgasmia and premature ejaculation (6;8). Among depressed women taking SSRIs, reported problems include diminished sexual desire and arousal as well as orgasm difficulties (5;6;9) with a 10-20% report of SSRI treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction (8).

Little is known about sexual side effects experienced by non-depressed midlife women taking SSRIs for VMS. Most trials to date evaluated libido and or pain as a single item in a check list or as a component of a menopause quality of life scale (2;10-16). Possible sexual dysfunction as an adverse effect of SSRI therapy is a major consideration for peri- and postmenopausal women with VMS and may influence choices and acceptability of therapies. Sexual function (libido, lubrication, orgasm and pain) may already be altered during the menopause transition (17-20) and any medications that could potentially worsen already diminished sexual function may not be acceptable to women.

We hypothesized that if sexual function is diminished among non-depressed menopausal women taking SSRIs for VMS, desire, arousal, and orgasm domains would most likely be affected. Alternatively, it also seemed plausible that overall sexual function may improve in women with effective treatment of bothersome VMS, mood and sleep. Our study provided a unique opportunity to prospectively evaluate sexual function among non-depressed midlife women in a double-blind randomized trial comparing the use of escitalopram versus placebo among peri- and postmenopausal women with bothersome VMS. We also compared the effect of escitalopram versus placebo on 6 female sexual domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) and sexually-related personal distress.

Materials and Methods

Details regarding study design and methodology are published (4). The study was a multi-site, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating site. Participants provided written informed consent.

The trial was conducted at Menopause strategies - Finding Lasting Answers for Symptoms and Health (MsFLASH) network sites in Philadelphia, Boston, Oakland and Indianapolis. Participants were recruited by mail (July 2009 - June 2010). Eligible women were ages 40-62 years, perimenopausal or postmenopausal, including those who had had a hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy. Women were required to have 28 or more hot flashes or night sweats per week, as well as bothersome, severe vasomotor symptoms or both VMS on 4 or more days per week. Women were excluded if they used psychotropic medications, prescription or over-the-counter hot flash therapies, hormonal therapies, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or aromatase inhibitors. In addition, women were excluded if they had a major depression episode or major alcohol or drug addiction problems in the past year, suicide attempt in the past 3 years, lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or psychosis or any major pre-existing health problems that precluded participation.

Eligible participants were screened initially by phone and then had 2 in-person visits. Stratified randomization of eligible women in equal proportions to escitalopram 10 mg per day or a matching placebo pill occurred at the second visit, using a dynamic randomization algorithm to ensure comparability between treatment groups with respect to race and clinical site (21). For women whose VMS had not improved by week-4, their daily “dose” was increased from 1 to 2 pills until 8 weeks.

Women received a phone call one week after randomization to assess adverse events and adherence. Additional clinic visits occurred at weeks 4 and 8.

Primary outcomes for the trial are published (4). In these analyses, sexual function was measured using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (Appendixes 1 and 2) (22). FSFI questions are coded from 0 to 5 in 6 sexual domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain). The maximum score for each domain is 6, obtained by summing scores for all questions and multiplying by a correction factor. The final composite score is a sum of the 6 domain scores, and ranges from 2 (not sexually active and no desire) to 36. A single question, “Over the past 4 weeks, how satisfied have you been with your overall sex life?” was inadvertently omitted from the questionnaire; a value for this question was imputed for each woman as an average of their answers to the 2 other questions in the FSFI satisfaction domain.

To determine how bothered or distressed women were by their levels of sexual function, we adapted a single question from the Female Sexual Distress Scale, “In the past 4 weeks, how often did you feel distressed or bothered about your sex life?” Scoring was: 0= never, 1= rarely, 2= occasionally, 3= frequently or 4= always and was analyzed as a binary outcome, with 0, 1 and 2 defined as “not or minimally” and 3, 4 defined as “frequently or always” distressed.

Possible correlates of sexual function were assessed using self-reported questionnaires completed at baseline and follow-up. These included: (a) VMS frequency, severity, bother and interference, (b) sleep, (c) stress, (d) depressed mood and anxiety, (e) menopausal status (transition, postmenopause), (f) self-reported health on a 5-point scale, and (g) other variables, including smoking, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and demographic information.

Adverse events (AEs), including sexual dysfunction, were obtained at each visit using a self-administered questionnaire listing 12 commonly reported SSRI-related AEs. Newly-emergent AEs were identified by comparing AE reports during treatment to the subjects' baseline reports.

All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle and included all randomized participants with follow-up FSFI measurements, which were collected irrespective of study medication adherence. Baseline characteristics were compared across groups using t-tests or chi-square tests. Our primary aims were to compare the change in sexual function from baseline to 4 and 8 weeks among a) all randomized women and b) participants who were sexually active at baseline. The primary analysis consisted of the treatment group estimated contrast from a linear regression model summarizing total FSFI score at 4 and 8 weeks as a function of group and baseline FSFI. Generalized estimating equations were applied to account for correlation between participants' repeated measures.

Our secondary aims were to compare across treatment group, the changes from baseline to week 8, in 1) the frequency of all women reporting distress or bother and 2) various FSFI sexual domains among sexually active women. Also, 3) to evaluate the association of baseline to week 8 changes in total FSFI with those in VMS frequency, sleep quality (PSQI), stress (PSS) and anxiety (HSCL). The first of these aims was analyzed via logistic regression model summarizing the prevalence of distress at week 8 as a function of treatment assignment and baseline distress. The changes in sexual domain scores were analyzed via linear regression models of the week 8 scores as functions of treatment assignment and the corresponding baseline domain score, followed by comparing the proportions of women in the 2 treatment arms with at least 1 and 2 point decreases in any given domain via chi-square tests (a priori, 2-point change differences were considered clinically significant).

All models were adjusted for race and site because the trial randomization was stratified by these factors. Factors considered as potential confounders included baseline age, education, menopausal status, BMI, sleep, mood (PHQ), VMS frequency, stress and self-reported health. A factor was included as a confounder if the estimated coefficient of interest differed by 10% or more between the multivariable models with and without the factor.

The planned sample size of the trial (90 women per treatment group) was determined by the primary trial endpoints (hot flash frequency and severity) (4), although the sample sizes provided 80% power to detect a 10% difference between groups in the composite FSFI. Reported p-values are based on the Wald statistic. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with 2-sided p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant. Secondary analyses are considered exploratory and should be interpreted with caution.

Results

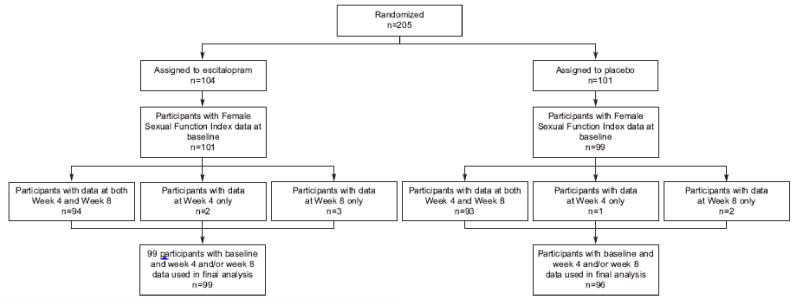

The study population consisted of 200 participants (Figure 1) after excluding 5 participants missing responses to the FSFI questions at baseline. Women in our study were well educated, 59% were married or living with a partner, and 39% were obese. Approximately 22% of women had had a hysterectomy and 82% were postmenopausal. None had major depressive disorder, only 6% had moderate depressive symptoms, 5% were moderately anxious, and 40% had poor sleep quality. Overall, participant's stress levels, PSS score mean of 13.5 (SD 7.4), were similar to the standard norm of 13.7 (SD 6.6) (23); 14.3% had PSS scores > 20. Women had an average of almost 10 hot flashes per day. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study participant sexual function data collection.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline by Treatment Arm.

| Escitalopram (n =101) | Placebo (n=99) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristic* | n | % | n | % |

| Age at screening, mean (SD) | 53.3 (4.2) | 54.3 (3.9) | ||

| 42 - 49 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 9 |

| 50 - 54 | 47 | 47 | 46 | 46 |

| 55 - 59 | 29 | 29 | 35 | 35 |

| 60 - 62 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 52 | 51 | 48 | 48 |

| African American | 45 | 45 | 47 | 47 |

| Other | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Clinic site | ||||

| Boston | 24 | 24 | 19 | 19 |

| Indianapolis | 16 | 16 | 17 | 17 |

| Oakland | 30 | 30 | 25 | 25 |

| Philadelphia | 31 | 31 | 38 | 38 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than a high school diploma or high school equivalency degree | 15 | 15 | 21 | 21 |

| School or training after high school | 44 | 44 | 41 | 41 |

| College graduate | 42 | 42 | 37 | 37 |

| Marital status: married, or living with partner | 63 | 62 | 55 | 56 |

| Currently smoking | 19 | 19 | 25 | 25 |

| Alcohol use (seven or more drinks per week) | 12 | 12 | 16 | 16 |

| Body mass index (m/kg2), mean (SD) | 28.7 (6.7) | 29.6 (6.2) | ||

| Lower than 25 | 31 | 31 | 21 | 21 |

| 25 – 29 | 32 | 32 | 38 | 38 |

| 30 or higher | 38 | 38 | 39 | 39 |

| Menopause status | ||||

| Postmenopause | 81 | 80 | 82 | 83 |

| Late transition | 17 | 17 | 14 | 14 |

| Early transition | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Hysterectomy | 23 | 23 | 20 | 20 |

| Oophorectomy† | 14 | 14 | 10 | 10 |

| Self-reported health | ||||

| Excellent | 18 | 18 | 13 | 13 |

| Very Good | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Good | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Fair | 7 | 7 | 11 | 11 |

| Poor | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| PHQ-9 Depression score, mean (SD) | 3.2 (3.1) | 2.9 (3.2) | ||

| No depression (0-4) | 74 | 73 | 76 | 77 |

| Mild depression (5-9) | 23 | 23 | 15 | 15 |

| Moderate+ depression (10-13) | 4 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| Sexually active | 75 | 74 | 70 | 71 |

| Sexual function (FSFI), mean (SD) | 16.1 (11.2) | 16.4 (12.6) | ||

| Poor (less than 26.55) | 81 | 80 | 70 | 71 |

| Good (26.55 or higher) | 20 | 20 | 29 | 29 |

| Personal distress (FSDS), frequently or always | 24 | 24 | 17 | 17 |

| Hot flash frequency per day, mean (SD) | 9.9 (6.3) | 9.6 (4.9) | ||

| Vaginal estrogen use in past 2 months | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

SD, standard deviation; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index; FSDS, Female Sexual Distress Scale.

p > 0.05 for all comparisons by treatment group as tested by t test or chi-square.

Three women randomized to escitalopram and two women randomized to placebo also each underwent a hysterectomy.

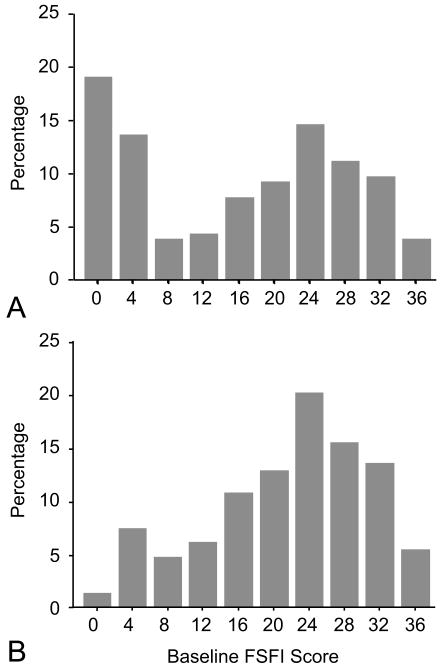

Median composite baseline FSFI score was 18.1 (interquartile range [IQR] 2.4, 26.5). Only 74% of women on escitalopram and 71% on placebo were sexually active at baseline. The distribution of baseline composite sexual function scores was bimodal for all women, but displayed a single mode among those who were sexually active at baseline (Figure 2). In the latter subgroup, median composite baseline FSFI score was 22.8 (IQR 17.4, 27.0) in the escitalopram group and 23.6 (IQR 14.9, 31.0) in the placebo group.

Figure 2.

Distribution of baseline Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) composite scores among (A) all women and (B) women sexually active at baseline.

A total of 195 participants were available for analysis of sexual function (FSFI score at week-4, week 8 or both), 99 in the escitalopram group and 96 in the placebo group. After adjustment for race, site and baseline FSFI score in a linear regression model, treatment with escitalopram did not affect composite FSFI score at follow-up as compared to placebo (p=0.18 overall treatment effect, Table 2). This same analysis was repeated among the women who were sexually active at baseline with similar results (p=0.47 overall treatment effect, Table 2). Fifty-three percent of participants assigned to escitalopram and 72% assigned to placebo received an increased dose at week-4. If anything, scores improved from 4 to 8 weeks; therefore the increase in dose from 10 to 20 mg at the 4-week visit among some participants did not appear to adversely affect sexual function. Adjustment for other potential confounders did not alter the results of the treatment arm comparisons.

Table 2. Sexual Function (Female Sexual Function Index) at Weeks 4and 8 by Treatment Arm.

| Escitalopram | Placebo | Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| All Women | |||||

| Baseline | 99 | 15.9 (13.7, 18.2) | 96 | 16.3 (13.8, 18.9) | -0.4 (-3.8, 2.9) |

| Change at Week 4 | 96 | -0.3 (-1.7, 1.2) | 94 | 0.8 (-1.1, 2.7) | -1.1 (-3.4, 1.3) |

| Change at Week 8 | 97 | 0.1 (-1.5, 1.7) | 95 | 2.0 (0.2, 3.8) | -1.9 (-4.3, 0.5) |

| Sexually Active at Baseline | |||||

| Baseline | 73 | 20.9 (18.9, 22.9) | 68 | 22.2 (19.8, 24.6) | -1.3 (-4.4, 1.8) |

| Change at Week 4 | 71 | -1.0 (-2.8, 0.8) | 67 | -0.7 (-2.9, 1.4) | -0.3 (-3.0, 2.5) |

| Change at Week 8 | 72 | -0.4 (-2.4, 1.5) | 67 | 0.9 (-1.1, 2.8) | -1.3 (-4.1, 1.5) |

Comparison of women randomized to escitalopram compared to placebo in a linear model of the outcome as a function of intervention arm and adjusted for race, clinical center, and baseline Female Sexual Function Index; P=0.18 for comparison of all women and P=0.47 of women sexually active at baseline. Only participants with baseline and week 4 and, or week 8 data were included in the analyses.

Forty-one of 199 participants (n=24 escitalopram, n=17 placebo) reported sexually-related personal distress at baseline (FSDS=3 or 4). This decreased to 33 of 195 participants (n=15 escitalopram, n=18 placebo) at 8 weeks. There was no significant increase in sexually-related personal distress among women taking escitalopram compared to placebo (p=0.73).

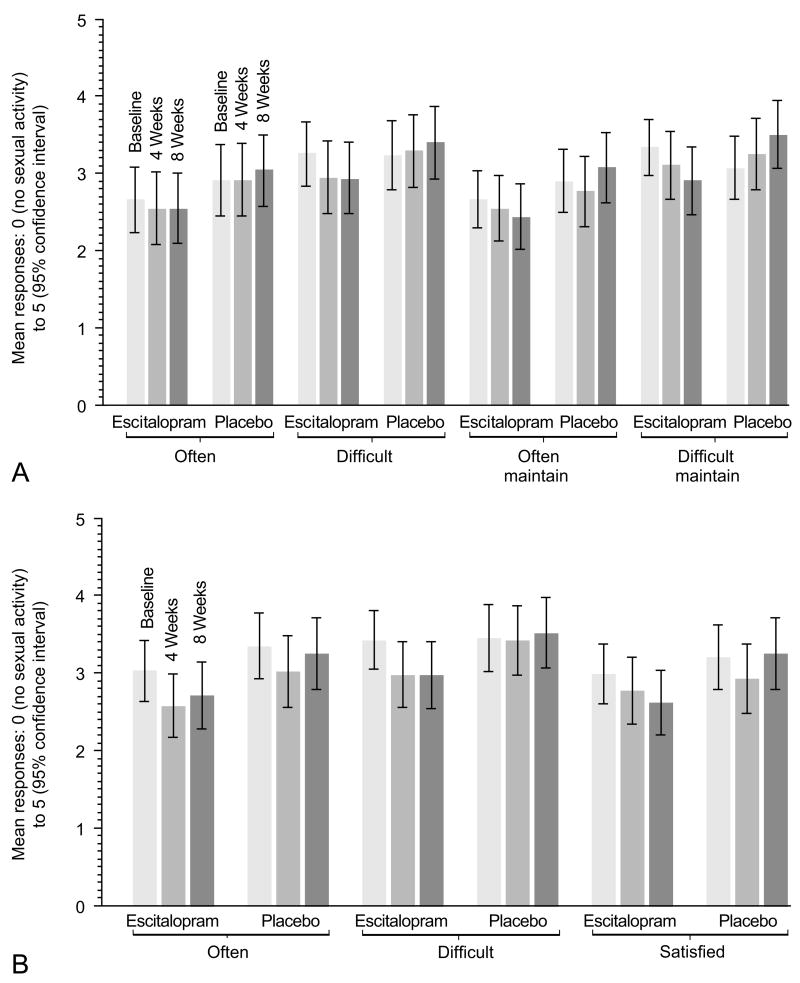

Changes in specific FSFI domains from baseline to week-8 were compared by treatment group, among those women who were sexually active at baseline (Table 3). There was a small statistically significant difference in mean change between groups in the lubrication domain (p=0.02) and a marginal difference that did not reach statistical significance in the orgasm domain (p=0.07). The different items in the lubrication and orgasm domains showed minimal mean changes from baseline to week-4 and 8 with overlapping confidence intervals (Figure 3). Among women who reported being sexually active on orgasm-related questions at baseline (126 or 65% of study participants), orgasmic function domain scores were reduced by at least 1 point, out of 6 points, in 33% of escitalopram-treated and 15% of placebo-treated women (p=0.02) and by at least 2 points in 15% of escitalopram-treated and 10% of placebo-treated women (p=0.39) at week-8. The proportion of sexually active women with anorgasmia did not vary by treatment group. Frequency of anorgasmia in the women taking escitalopram was 13%, 11% and 14% at baseline, 4 and 8 weeks, respectively. Frequency of anorgasmia in the women taking placebo was 6%, 10% and 7% at baseline, 4 and 8 weeks, respectively. Among the 130 participants who reported being sexually active on lubrication-related questions at baseline, lubrication domain scores were reduced at week-8 by at least 1 point, out of 6 points, in 17% escitalopram-treated and 10% of placebo-treated women (p=0.21), and by at least 2 points, in 12% escitalopram-treated and 7% of placebo-treated women (p=0.32).

Table 3. Change in Sexual Function Domains from Baseline to Week 8 by Treatment Arm among Participants With Sexual Activity at Baseline.

| Escitalopram | Placebo | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Sexual Function Index Domain | n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | P* |

| Desire | 73 | 0.3 (0, 0.5) | 68 | 0.1 (-0.2, 0.4) | 0.2 (-0.2, 0.6) | 0.84 |

| Arousal | 73 | -0.2 (-0.5, 0.2) | 68 | -0.1 (-0.5, 0.3) | -0.1 (-0.6, 0.4) | 0.56 |

| Lubrication | 73 | -0.3 (-0.7, 0.1) | 68 | 0.3 (-0.1, 0.7) | -0.6 (-1.2, -0.1) | 0.02 |

| Orgasm | 73 | -0.5 (-0.9, 0) | 68 | 0 (-0.4, 0.5) | -0.5 (-1.1, 0.1) | 0.07 |

| Satisfaction | 72 | 0.3 (-0.2, 0.7) | 68 | 0.2 (-0.3, 0.6) | 0.1 (-0.6, 0.7) | 0.83 |

| Pain | 73 | 0 (-0.6, 0.5) | 67 | 0.3 (-0.2, 0.9) | -0.3 (-1.1, 0.4) | 0.65 |

P-value from comparison of escitalopram compared to placebo in a linear model of the week 8 Female Sexual Function Index domain score as a function of intervention arm and adjusted for race, clinical center, and baseline Female Sexual Function Index domain score.

Figure 3.

Mean and 95% confidence intervals of responses to questions in the (A) Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) lubrication domain and (B) FSFI orgasm domain at baseline, 4 and 8 weeks among women who were sexually active at baseline (n=73 escitalopram, n= 67 placebo).

Y-axis: possible scores ranged from 0= poor to 5= maximum function.

X-Axis: Sexual function items. Questions for lubrication included: “Often”= Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you become lubricated (wet) during sexual activity or intercourse?; “Difficult“= How difficult was it to become lubricated (wet) during sexual activity or intercourse?; “Often Maintain” = How often did you maintain your lubrication (wetness) until completion of sexual activity or intercourse?; and “Difficult Maintain” = How difficult was it to maintain your lubrication (wetness) until completion of sexual activity or intercourse? Changes in domain scores (weighted average of all domain item scores) from baseline to 8 weeks, comparing escitalopram to placebo, were significant for lubrication (p=0.02), but not orgasm (p=0.07).

We evaluated the characteristics of those women with at least a one point decrease in the lubrication or orgasm domain in the escitalopram and placebo groups with regard to anxiety, VMS frequency, stress and sleep at baseline and at 8 weeks and found no significant associations. Analyses were repeated without imputation of the missing question in the satisfaction domain and findings did not change.

Newly emergent AEs related to sexual function did not differ between groups. Decreased sexual desire or ability was reported in 11% of women in the escitalopram group (n=7) and in 12% of women in the placebo group (n=8).

Discussion

Escitalopram at doses of 10 or 20 mg/day did not significantly alter overall sexual function among non-depressed midlife women, as compared to placebo, using a validated sexual function questionnaire, the FSFI (22). We found diminished lubrication and a marginal change in orgasm, that did not reach statistical significance, among women taking escitalopram; the clinical significance of these findings require additional study in larger populations. A small proportion of women who were sexually active at baseline reported experiencing treatment-related changes in lubrication or orgasm that may be clinically meaningful such that domain response scores decreased at least 2 points from being approximately, “equally satisfied/dissatisfied” to “very dissatisfied” for example. These differences (5 percent more women taking escitalopram reported diminished function as compared to placebo) were not statistically significant between groups. There was no evidence of escitalopram-related anorgasmia in this sexually active subgroup. No differences in other sexual function domains, including desire, arousal, satisfaction or pain, were observed.

Our findings support observations from biologic and epidemiologic studies of serotonin and SSRI effects on female sexual function. Female sexual physiology is complex and the changes that occur in midlife women are poorly understood, though it is clear that sexual function in women decreases with age (18;19). SSRIs act by increasing the availability of serotonin at synapses which can then inhibit dopamine centrally, affecting arousal and orgasm. Increased serotonin may also up- or down-regulate serotonin receptors, over 95% of which are present peripherally, thus modulating arteriole vasodilation and vasoconstriction, mechanisms likely important for lubrication, arousal and normal orgasmic function (24). Anorgasmia is a well described specific side effect of SSRI's among women with clinical depression or PMDD (7;8). Diminished lubrication, on the other hand, is not commonly described as being associated with SSRI use in either of these populations (8;25). Peri- and postmenopausal women are more likely to have problems with lubrication prior to SSRI treatment, therefore our findings may be explained by an already diminished baseline ability to lubricate, reducing the amount of change needed to achieve a clinically significant effect with the addition of an SSRI.

There is only one other report of SSRI therapy for VMS in non-depressed midlife women with detailed sexual function information (26). Although women in that trial did not find benefit for VMS with sertraline as compared with placebo, significant worsening in FSFI domains for arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain were observed. Others have evaluated SSRIs for VMS, but sexual function was assessed by a simple check list of side effects or a single sexual function question, usually related to desire, imbedded in a quality of life measure. In an extensive review of 16 studies of SSRIs and SNRIs for VMS, sexual function side effects were not reported as increased above placebo (2). Other studies concur with these findings (10-13;15;16).

Only a few studies have specifically studied the SSRI we used, escitalopram, for either PMDD (27), major depressive disorder (8) or VMS (28); some degree of sexual dysfunction was reported in all 3 studies, but again, sexual function was not measured with a structured assessment of the various female sexual domains. In a 12-week PMDD trial, escitalopram treatment-emergent effects of diminished libido (10-22%) and decrease in orgasm function (14-22%) were observed beyond the baseline reported for placebo (9% and 7%, respectively) (27). In depressed individuals, escitalopram was associated with 10-20% short-term treatment–emergent sexual dysfunction as compared with placebo; however after 12 weeks, this was no longer significant (8).Lastly, in an 8-week pilot study of 25 women taking escitalopram for VMS, 4 (16%) developed diminished libido and in 2 (8%) developed anorgasmia, although there was no comparison group.

Most studies in depressed populations report sexual function does not vary by SSRI type, including citalopram, venlafaxine, paroxetine, fluoxetine and sertraline (8;24;29). Others, however, suggest that female orgasm disorder is most commonly associated with paroxetine and venlafaxine (6;9;30), and an improvement in SSRI or SNRI induced sexual dysfunction may be achieved by switching to escitalopram (31).

Details reported on sexual function in the Penn Ovarian Aging cohort inform the interpretation of our findings (21). The majority of women in that study were ages 40-54, whereas the mean age of women in our study was 54 years. Gracia et al also noted a bimodal distribution in the composite FSFI score and assigned a cut point of normal sexual function at 20, rather than the cut point of 26.5 used in a large population of women, mean age 36.2 (range 18-74) (32). The FSFI scores among our sexually active, predominantly postmenopausal women were quite comparable to those observed in the Penn Ovarian Aging cohort, both overall and among the 6 female sexual function domains.

Strengths of this study include detailed sexual function information, similar numbers of African American and white women, the inclusion of peri- and postmenopausal women, high adherence to therapy, and a low dropout rate (95% provided response data at week 8), comparable across arms. We note that although this was a community-based sample, the volunteer participants may be a select group who were motivated to seek treatment. It could be, at recruitment, that after describing sexual dysfunction as a possible side effect, women who already had sexual dysfunction were not concerned regarding a worsening effect, and were apt to enroll in the study. On the other hand, women worried about sexual dysfunction may have been apt to decline participation. An 8-week treatment interval may be considered brief, but data indicate that this interval is sufficient time to assess sexual function side effects (33); others suggest symptoms improve through time (8). Longer studies, beyond 8 weeks, of sexual function in healthy women have not been done. We examined several potential modulating factors of sexual function and escitalopram but had limited power to assess any interactions, and other factors that we did not measure could have confounded the results.

Our findings are reassuring that among healthy non-depressed midlife women with bothersome VMS, escitalopram 10-20 mg/day did not affect overall sexual function and only minimally affected orgasmic response and lubrication, with no effect on sexually-related personal distress. Our report is important for women considering the use of escitalopram for management of VMS. A key consideration for all menopausal therapies is medication tolerance and adverse events. While a majority reported common mild side effects of escitalopram after initiating treatment, there were no serious AEs and equal numbers of women reported sexual function AEs in the 2 groups. Further detailed evaluation of sexual function in midlife women is warranted, particularly among healthy non-depressed women taking SSRIs for VMS, and particularly to further assess any changes in the lubrication and orgasm domains.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joseph Larson for statistical support.

Supported by a cooperative agreement issued by the National Institute of Aging (NIA), in collaboration with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) and the Office of Research and Women's Health (ORWH), and grants U01 AG032656, U01AG032659, U01AG032669, U01AG032682, U01AG032699, U01AG032700 from the NIA. At the Indiana University site, the project was funded in part with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, funded in part by grant UL1 RR025761 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. Escitalopram and matching placebo were supplied by Forest Research Institute.

Appendix 1.

Female Sexual Function Index Scoring.

| Question | Response Options |

|---|---|

| 1. Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you feel sexual desire or interest? | 5 = Almost always or always |

| 4 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 2 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 1 = Almost never or never | |

| 2. Over the past 4 weeks, how would you rate your level (degree) of sexual desire or interest? | 5 = Very high |

| 4 = High | |

| 3 = Moderate | |

| 2 = Low | |

| 1 = Very low or none at all | |

| 3. Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you feel sexually aroused (“turned on”) during sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Almost always or always | |

| 4 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 2 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 1 = Almost never or never | |

| 4. Over the past 4 weeks, how would you rate your level of sexual arousal (“turn on”) during sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Very high | |

| 4 = High | |

| 3 = Moderate | |

| 2 = Low | |

| 1 = Very low or none at all | |

| 5. Over the past 4 weeks, how confident were you about becoming sexually aroused during sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Very high confidence | |

| 4 = High confidence | |

| 3 = Moderate confidence | |

| 2 = Low confidence | |

| 1 = Very low or no confidence | |

| 6. Over the past 4 weeks, how often have you been satisfied with your arousal (excitement) during sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Almost always or always | |

| 4 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 2 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 1 = Almost never or never | |

| 7. Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you become lubricated (“wet”) during sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Almost always or always | |

| 4 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 2 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 1 = Almost never or never | |

| 8. Over the past 4 weeks, how difficult was it to become lubricated (“wet”) during sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 1 = Extremely difficult or impossible | |

| 2 = Very difficult | |

| 3 = Difficult | |

| 4 = Slightly difficult | |

| 5 = Not difficult | |

| 9. Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you maintain your lubrication (“wetness”) until completion of sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Almost always or always | |

| 4 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 2 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 1 = Almost never or never | |

| 10. Over the past 4 weeks, how difficult was it to maintain your lubrication (“wetness”) until completion of sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 1 = Extremely difficult or impossible | |

| 2 = Very difficult | |

| 3 = Difficult | |

| 4 = Slightly difficult | |

| 5 = Not difficult | |

| 11. Over the past 4 weeks, when you had sexual stimulation or intercourse, how often did you reach orgasm (climax)? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 1 = Almost always or always | |

| 2 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 4 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 5 = Almost never or never | |

| 12. Over the past 4 weeks, when you had sexual stimulation or intercourse, how difficult was it for you to reach orgasm (climax)? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 1 = Extremely difficult or impossible | |

| 2 = Very difficult | |

| 3 = Difficult | |

| 4 = Slightly difficult | |

| 5 = Not difficult | |

| 13. Over the past 4 weeks, how satisfied were you with your ability to reach orgasm (climax) during sexual activity or intercourse? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Very satisfied | |

| 4 = Moderately satisfied | |

| 3 = About equally satisfied and dissatisfied | |

| 2 = Moderately dissatisfied | |

| 1 = Very dissatisfied | |

| 14. Over the past 4 weeks, how satisfied have you been with the amount of emotional closeness during sexual activity between you and your partner? | 0 = No sexual activity |

| 5 = Very satisfied | |

| 4 = Moderately satisfied | |

| 3 = About equally satisfied and dissatisfied | |

| 2 = Moderately dissatisfied | |

| 1 = Very dissatisfied | |

| 15. Over the past 4 weeks, how satisfied have you been with your sexual relationship with your partner? | 5 = Very satisfied |

| 4 = Moderately satisfied | |

| 3 = About equally satisfied and dissatisfied | |

| 2 = Moderately dissatisfied | |

| 1 = Very dissatisfied | |

| 16. Over the past 4 weeks, how satisfied have you been with your overall sexual life? | 5 = Very satisfied |

| 4 = Moderately satisfied | |

| 3 = About equally satisfied and dissatisfied | |

| 2 = Moderately dissatisfied | |

| 1 = Very dissatisfied | |

| 17. Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you experience discomfort or pain during vaginal penetration? | 0 = Did not attempt intercourse |

| 1 = Almost always or always | |

| 2 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 4 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 5 = Almost never or never | |

| 18. Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you experience discomfort or pain following vaginal penetration? | 0 = Did not attempt intercourse |

| 1 = Almost always or always | |

| 2 = Most times (more than half the time) | |

| 3 = Sometimes (about half the time) | |

| 4 = A few times (less than half the time) | |

| 5 = Almost never or never | |

| 19. Over the past 4 weeks, how would you rate your level (degree) of discomfort or pain during or following vaginal penetration? | 0 = Did not attempt intercourse |

| 1 = Very high | |

| 2 = High | |

| 3 = Moderate | |

| 4 = Low | |

| 5 = Very low or none at all | |

Appendix 2.

Female Sexual Function Index Domain Scores and Full Scale Score.

The individual domain scores and full scale (overall) score of the Female Sexual Function Index can be derived from the computational formula outlined in the table below. For individual domain scores, add the scores of the individual items that comprise the domain and multiply the sum by the domain factor (see below). Add the six domain scores to obtain the full scale score. It should be noted that within the individual domains, a domain score of zero indicates that the subject reported having no sexual activity during the past month. Subject scores can be entered in the right hand column.

| Domain | Questions | Score Range | Factor | Minimum Score | Maximum Score | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desire | 1, 2 | 1 – 5 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 6.0 | |

| Arousal | 3, 4, 5, 6 | 0 – 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 6.0 | |

| Lubrication | 7, 8, 9, 10 | 0 – 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 6.0 | |

| Orgasm | 11, 12, 13 | 0 – 5 | 0.4 | 0 | 6.0 | |

| Satisfaction | 14, 15, 16 | 0 (or 1) – 5 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 6.0 | |

| Pain | 17, 18, 19 | 0 – 5 | 0.4 | 0 | 6.0 | |

| Full Scale Score Range | 2.0 | 36.0 | ||||

FSFI Scoring Appendix. Available at: http://www.fsfi-questionnaire.com/FSFI%20Scoring%20Appendix.pdf. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Joffe received research support from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals and has performed advisory or consulting work for Sanofi-Aventis/Sunovion, Pfizer, and Noven. Dr. Shifren has been a research consultant to the New England Research Institutes and received research support from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Freeman has received research support from Forest Research, Inc., Wyeth, and Anodyne Pharmaceuticals.

The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented at the International Menopause Society Meeting, Rome Italy, June 8-11, 2011 and the North American Menopause Society Meeting, Washington DC, September 21-24, 2011.

Contributor Information

Susan D. Reed, Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Katherine A. Guthrie, Data Coordinating Center, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA.

Hadine Joffe, Departments of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Jan L. Shifren, Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Rebecca A. Seguin, Data Coordinating Center, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA.

Ellen W. Freeman, Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapkin AJ. Vasomotor symptoms in menopause: physiologic condition and central nervous system approaches to treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, Sternfeld B, Cohen LS, Joffe H, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:267–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton AH, Pradko JF, Croft HA, Montano CB, Leadbetter RA, Bolden-Watson C, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:357–66. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregorian RS, Golden KA, Bahce A, Goodman C, Kwong WJ, Khan ZM. Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1577–89. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown J, O' Brien PM, Marjoribanks J, Wyatt K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD001396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton A, Keller A, McGarvey EL. Burden of phase-specific sexual dysfunction with SSRIs. J Affect Disord. 2006;91:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Cherry C, Houck P, Kupfer DJ. Prospective assessment of sexual function in women treated for recurrent major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archer DF, Seidman L, Constantine GD, Pickar JH, Olivier S. A double-blind, randomly assigned, placebo-controlled study of desvenlafaxine efficacy and safety for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:172–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton DL, LaVasseur BI, Sloan JA, Stawis AN, Flynn KA, Dyar M, et al. Phase III, placebo-controlled trial of three doses of citalopram for the treatment of hot flashes: NCCTG trial N05C9. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3278–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon PR, Kerwin JP, Boesen KG, Senf J. Sertraline to treat hot flashes: a randomized controlled, double-blind, crossover trial in a general population. Menopause. 2006;13:568–75. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000196595.82452.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalay AE, Demir B, Haberal A, Kalay M, Kandemir O. Efficacy of citalopram on climacteric symptoms. Menopause. 2007;14:223–9. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000243571.55699.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:259–66. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares CN, Arsenio H, Joffe H, Bankier B, Cassano P, Petrillo LF, et al. Escitalopram versus ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone acetate for symptomatic peri- and postmenopausal women: impact on depression, vasomotor symptoms, sleep, and quality of life. Menopause. 2006;13:780–6. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000240633.46300.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speroff L, Gass M, Constantine G, Olivier S. Efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine succinate treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:77–87. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000297371.89129.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF, Jr, Shen S, Cain VS, Ory M, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16:442–52. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181948dd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennerstein L, Dudley E, Burger H. Are changes in sexual functioning during midlife due to aging or menopause? Fertil Steril. 2001;76:456–60. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01978-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennerstein L, Guthrie JR, Hayes RD, Derogatis LR, Lehert P. Sexual function, dysfunction, and sexual distress in a prospective, population-based sample of mid-aged, Australian-born women. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2291–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gracia CR, Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Mogul M. Hormones and sexuality during transition to menopause. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:831–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258781.15142.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop JR, Ellingrod VL, Akroush M, Moline J. The association of serotonin transporter genotypes and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)-associated sexual side effects: possible relationship to oral contraceptives. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:207–15. doi: 10.1002/hup.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safarinejad MR. Reversal of SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction by adjunctive bupropion in menstruating women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:370–8. doi: 10.1177/0269881109351966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grady D, Cohen B, Tice J, Kristof M, Olyaie A, Sawaya GF. Ineffectiveness of sertraline for treatment of menopausal hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:823–30. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258278.73505.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eriksson E, Ekman A, Sinclair S, Sorvik K, Ysander C, Mattson UB, et al. Escitalopram administered in the luteal phase exerts a marked and dose-dependent effect in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:195–202. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181678a28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Defronzo-Dobkin R, Menza M, Allen LA, Marin H, Bienfait KL, Tiu J. Escitalopram reduces hot flashes in nondepressed menopausal women: A pilot study. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21:70–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy SH, Fulton KA, Bagby RM, Greene AL, Cohen NL, Rafi-Tari S. Sexual function during bupropion or paroxetine treatment of major depressive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:234–42. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labbate LA, Grimes J, Hines A, Oleshansky MA, Arana GW. Sexual dysfunction induced by serotonin reuptake antidepressants. J Sex Marital Ther. 1998;24:3–12. doi: 10.1080/00926239808414663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashton AK, Mahmood A, Iqbal F. Improvements in SSRI/SNRI-induced sexual dysfunction by switching to escitalopram. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:257–62. doi: 10.1080/00926230590513474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman CC, Cunningham LA, Foster VJ, Batey SR, Donahue RM, Houser TL, et al. Sexual dysfunction associated with the treatment of depression: a placebo-controlled comparison of bupropion sustained release and sertraline treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1999;11:205–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1022309428886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]