Abstract

Modern medicine has greatly benefited from recent dramatic improvements in imaging techniques. The observation of physiological events through interactions manipulated at the molecular level offers unique insight into the function (and dysfunction) of the living organism. The tremendous advances in the development of nanoparticulate molecular imaging agents over the past decade have made it possible to noninvasively image the specificity, pharmacokinetic profiles, biodistribution, and therapeutic efficacy of many novel compounds.

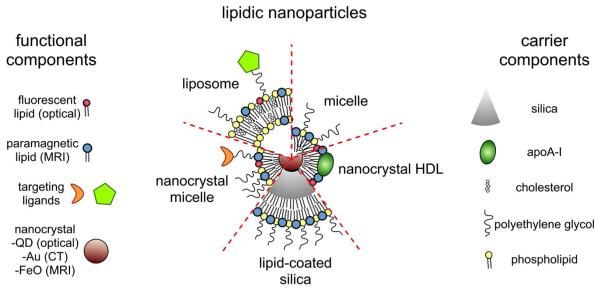

Several types of nanoparticles have demonstrated utility for biomedical purposes, including inorganic nanocrystals such as iron oxide, gold, and quantum dots. Moreover, natural nanoparticles, such as viruses, lipoproteins, or apoferritin—as well as hybrid nanostructures composed of inorganic and natural nanoparticles—have been applied broadly. However, among the most investigated nanoparticle platforms for biomedical purposes are lipidic aggregates, such as liposomal nanoparticles, micelles, and microemulsions. Their relative ease of preparation and functionalization—as well as the ready synthetic ability to combine multiple amphiphilic moieties—are the most important reasons for their popularity. Lipid-based nanoparticle platforms allow the inclusion of a variety of imaging agents, ranging from fluorescent molecules to chelated metals and nanocrystals.

In recent years, we have created a variety of multifunctional lipid-based nanoparticles for molecular imaging; many are capable of being used with more than one imaging technique (that is, with multimodal imaging ability). These nanoparticles differ in size, morphology, and specificity for biological markers. In this Account, we discuss the development and characterization of five different particles: liposomes, micelles, nanocrystal micelles, lipid-coated silica, and nanocrystal high-density lipoprotein (HDL). We also demonstrate their application for multimodal molecular imaging, with the main focus on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), optical techniques, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The functionalization of the nanoparticles and the modulation of their pharmacokinetics are discussed. Their application for molecular imaging of key processes in cancer and cardiovascular disease are shown. Finally, we discuss a recent development in which the endogenous nanoparticle HDL was modified to carry different diagnostically active nanocrystal cores to enable multimodal imaging of macrophages in experimental atherosclerosis. The multimodal characteristics of the different contrast agent platforms have proven to be extremely valuable for validation purposes and for understanding mechanisms of particle-target interaction at different levels, ranging from the entire organism down to cellular organelles.

Introduction

In recent years, the disciplines of nanomedicine and diagnostic imaging have increasingly joined forces, a development that was driven from both directions1,2. The past decade has witnessed tremendous advances in the field of nanoparticle facilitated molecular imaging, while non-invasive imaging has shown to be especially valuable to investigate aspects such as target specificity, pharmacokinetic profiles, biodistribution, as well as to assess therapeutic effects of nanoparticulate compounds2,3,4,5. Materials such as iron oxide and gold were recognized to have extraordinary features for diagnostics as well as therapeutics6,7. For example iron oxide nanoparticles have been employed extensively as contrast generating material for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)6, but can also be used for thermal ablation8, while gold is suitable for optical detection9 as well as for laser activated thermal ablation10. After their discovery, quantum dots (QDs), semiconductor nanocrystals, were soon recognized to be uniquely suited for bio-imaging, including in vivo fluorescence imaging and ex vivo immunofluorescence11. In addition to these inorganic nanoparticles polymeric nanoparticles, including dendrimers, have been explored extensively for the same purposes12. Natural nanoparticles, such as viruses or lipoproteins have also been broadly employed for a variety of applications, such as gene delivery and imaging13,14. Interestingly, natural nanoparticles can be combined with inorganic nanoparticles to create so-called hybrid nanostructures that can be tailored to specific applications15.

Nanoparticulate aggregates of lipids are among the nanoparticle platforms that have been investigated most extensively for biomedical purposes4,16. Liposomal nanoparticles have thus far been most successful, which has resulted in the FDA approval and clinical application of several liposomal formulations of cytostatic agents17. Micelles and microemulsions are thoroughly investigated for the delivery of hydrophobic compounds18,19, while lipids and other amphiphilic molecules can also function as coating for solid nanoparticles20,21,22. The relative ease of preparation and functionalization, the possibility to create a variety of lipid aggregate morphologies, and importantly, the ability to combine multiple amphiphilic molecules with different functionalities are the most important reasons for the popularity of lipidic nanoparticles. In addition, a variety of naturally occurring and fully synthetic lipids are commercially available. These include labeled lipids as well as lipids that are functionalized with polymers and reactive groups. Most of these lipids are based on naturally occurring phospholipids which enhances the biocompatibility of the structures formed.

In the field of (molecular) imaging lipid-based nanoparticle platforms allow the inclusion of a variety of imaging agents ranging from fluorescent molecules, such as rhodamine and Cy5.523,24, to chelated metals for MRI and nuclear imaging4, and nanocrystals, including QDs, FeO and gold20,22,25,26. Amphiphilic molecules tend to nestle and mix with the lipids, whereas hydrophobic compounds can be included in the core of micelles and microemulsions. The inclusion of hydrophobic compounds is not limited to small molecules only. Nanocrystals like QDs, capped with hydrophobic ligands, have also been demonstrated to efficiently incorporate in the core of micelles20,22,25,26 and microemulsions27.

The multimodality character of lipid nanoparticle platforms has significant advantages since it allows the visualization of a single platform using different techniques. This enables validation and co-localization using microscopic techniques. In addition, due to the complementarity of the different imaging modalities available, further information can be obtained, while different aspects of the process investigated can be validated and more thoroughly investigated at different levels.

In recent years, we have created a variety of multifunctional lipid-based nanoparticles4 for molecular imaging in our laboratories. These nanoparticles differ in size, morphology, multimodal imaging ability, and specificity for molecular targets expressed by cells. In this review we will discuss the development and characterization of the different platforms as well as their application for multimodality (molecular) imaging, with the main focus on MRI, optical techniques like confocal microscopy and fluorescence imaging, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We will demonstrate how such nanoparticles can be functionalized, and how to investigate and modulate their pharmacokinetics. In addition, we will show their application for molecular imaging of experimental cancer and cardiovascular disease to investigate processes such as angiogenesis, apoptosis, inflammation and lipoprotein metabolism. Lastly, a recent development will be discussed where an endogenous nanoparticle, high density lipoprotein (HDL), was modified to carry different diagnostically active nanocrystal cores for multimodality imaging.

Fluorescent and paramagnetic liposomes

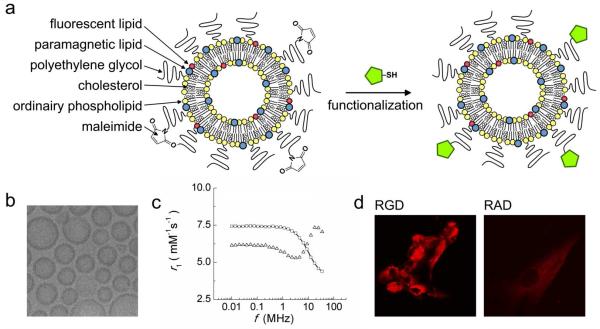

Liposomes, spherical, self-closed structures formed by one or several concentric lipid bilayers with an aqueous phase inside and between the lipid bilayers, are attractive carriers for MRI contrast agents28. In 2004 we introduced a paramagnetic and PEGylated liposomal MRI contrast agent that was additionally labeled with fluorophores to enable its visualization with fluorescence techniques (Figure 1a)23. Moreover this nanoparticle was functionalized with maleimide (distally at the PEG-chains) to allow covalent linkage with thiol exposing molecules via the sulfhydryl-maleimide coupling method (Figure 1a, right). Cryo-TEM showed the typical spherical morphology of the liposomes (Figure 1b)29.

Figure 1. Paramagnetic and fluorescent liposomes for target-specific imaging.

(a) Schematic of liposomes composed of the amphiphilic molecules indicated left. Thiol containing targeting ligands can be covalently linked to the maleimide containing liposomes. (b) Cryo-TEM reveals unilamellar vesicular structures. (c) NMRD-profiles of GD-DTPA (starts high and drops at higher field strengths) and paramagnetic liposomes that show a typical peak at clinically relevant field strengths. (d) Confocal microscopy of cultured endothelial cells (HUVEC) that had been incubated with αvβ3-specific RGD-liposomes and non-specific RAD-liposomes. Reproduced with permission from ref29 and ref30.

The longitudinal relaxivity r1, i.e. the potency of an MRI contrast agent to shorten the longitudinal relaxation time T1 can be plotted as function of field strength to obtain so-called nuclear magnetic resonance dispersion profiles (NMRD-profiles). In general the relaxivity is largely determined by the variations in the interplay between the rotation correlation time (τR) and the exchange of water molecules coordinated to a single Gd3+ chelate. Typical profiles with maximum intensities around clinically relevant field strengths of 20 to 60 MHz are obtained when Gd3+ chelates exhibit diminished mobility, which causes their tumbling rate τR to decrease, such as for liposomes (Figure 1c)29.

When equipped with H18/7 monoclonal antibodies, which have a high affinity for the cell adhesion molecule E-selectin, it was shown by both fluorescence microscopy and MRI that the liposomal contrast agent was preferentially associated with stimulated endothelial cells23. Subsequently to this study the liposomes were equipped with αvβ3-integrin specific RGD-peptides and non-specific RAD-peptides30. Incubations with human umbilical vein-derived endothelial cells revealed that the αvβ3-specific liposomes were taken up to a much higher extent than the RAD-conjugated control liposomes, as evidenced by confocal microscopy (Figure 1d) and MRI (not shown).

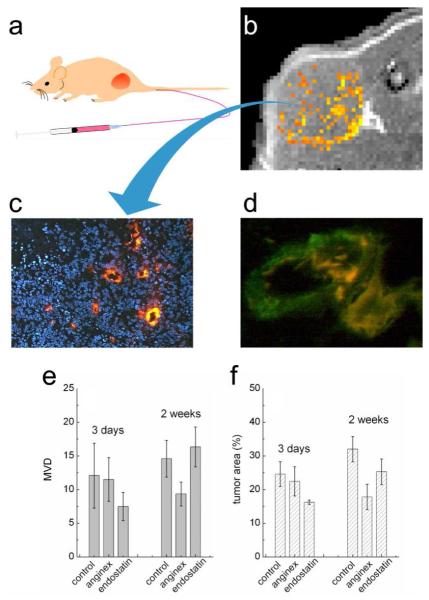

This αvβ3-specific liposomal system was extensively employed to visualize and quantify ongoing tumor angiogenesis in mouse models30,31. In a first in vivo study in tumor bearing mice30 it was shown that after intravenous administration (Figure 2a) the liposomes gave rise to MRI signal enhancement in the rim of the tumor (Figure 2b). The inclusion of the fluorophore also enabled visualization of the liposomes with immunofluorescent techniques in order to co-localize them with other relevant cellular structures. The patterns of red fluorescence observed in tumor sections (Figure 2c) are indicative of tumor blood vessel labeling by the RGD-functionalized liposomes. Additional staining with the endothelial cell specific antibodies directed to CD31 supported this interpretation, since a high degree of co-localization between the liposomes and tumor vessel endothelial cells was observed (Figure 2d).

Figure 2. MR molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis.

(a) Tumor bearing mice were intravenously injected with the dual modality liposomes. (b) MR image of a slice through the tumor of an animal that was injected with paramagnetic RGD-liposomes reveals pronounced signal increase in the tumor periphery (c) Fluorescence microscopy of DAPI colored ten-μm sections from dissected tumors of mice that were injected with RGD-liposomes. (d) Endothelial cell and liposome co-registration. Vessel staining was done with an endothelial cell specific CD31 antibody (green), while the red fluorescence represents the RGD-liposomes. RGD-liposomes were exclusively found within the vessel lumen or associated with vessel endothelial cells, indicative of a specific association with the angiogenic endothelium. (e, f) Groups of tumor bearing mice that were treated with the anti-angiogenic agents anginex and endostatin underwent molecular MRI, which was followed by quantitative histology of the microvessel density (MVD). (e) Quantification of MVD as mean number of vessels per 0.25 mm2. (f) The percentage of the tumor with significant MRI signal enhancement after intravenous injection with RGD-liposomes. Reproduced with permission from ref31.

In a subsequent study the above technology was employed to visualize and quantify ongoing tumor angiogenesis in mice that were treated with anti-angiogenic agents31. Traditional read-outs for therapeutic efficacy of such agents are tumor growth inhibition as well as microvessel density (MVD), since the agents have an inhibitory effect on neovascularization. Determination of MVD is an inherently invasive procedure and is usually achieved by staining multiple tumor sections for blood vessels and counting them. This number can be plotted for the different treatment groups, as was done in this study (Figure 2e). Molecular MRI with the αvβ3-specific liposomes allowed in vivo quantification of the percentage of the tumor volume that exhibits significant angiogenesis (Figure 2f). A high degree of correlation between ex vivo histology and in vivo molecular MRI was observed. Direct readouts of angiogenic molecular activity before, during, and after therapy should aid preclinical drug testing32. Therefore this technology may pave the path for more effective in vivo screening of anti-angiogenic agents, which will enable more judiciously selecting key compounds for clinical testing.

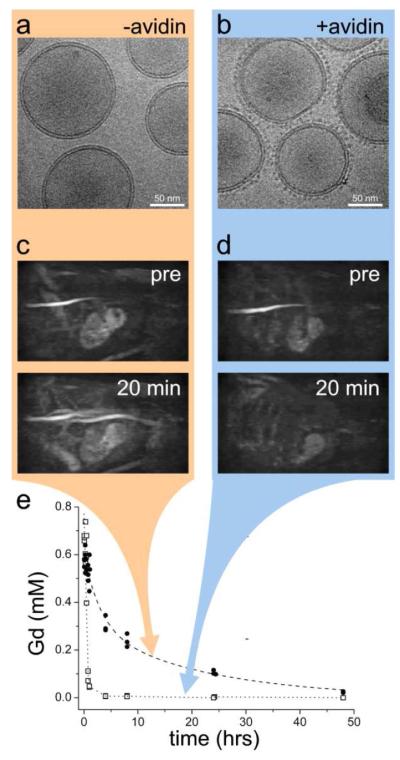

Next to target-specific imaging, functionalization of the liposomal system also allows for manipulating its pharmacokinetic profile. This was exemplified in a recent study by van Tilborg et al. where the pharmacokinetics of these liposomes, additionally labeled with biotin, were extensively studied using a variety of techniques, including cryogenic TEM (cryo-TEM), MRI, inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS), and immunofluorescence33. In vitro it was demonstrated using cryo-TEM that the liposomes cross-linked upon incubation with avidin (Figure 3a and b). Upon intravenous administration, it was anticipated that the biotinylated liposomes could be removed from the circulation upon infusion of avidin. In Figure 3c typical liposome enhanced MRI angiographs before and 20 minutes after the infusion of saline are depicted and revealed no enhanced clearance of the liposomes. Conversely, upon injection of avidin a rapid decrease of vascular signal was observed, indicative of induced clearance of the liposomes from the circulation (Figure 3d). Gd determinations of sequential blood draws confirmed the aforementioned observation. The majority of the liposomes were cleared form the circulation within one hour after infusing avidin, while in the control situation over 90 % of the initial dose was still present in the blood (Figure 3e).

Figure 3. Avidin induced clearance of biotinylated liposomes.

Cryo-TEM images of biotinylated paramagnetic liposomes (a) prior to and (b) after overnight incubation with avidin. (c, d) Maximum intensity projections of three-dimensional MRI data sets. Mice that had been injected with paramagnetic biotin-liposomes (pre), followed by the infusion of (c) saline or (d) avidin. (e) Blood Gd levels following intravenous injection of biotinylated liposomes. Avidin (open symbols) or saline infusion (closed symbols) was started 26 minutes after liposome injection. Data points for mice that received avidin are interpolated to guide the eye (dotted line). Reproduced with permission from ref33.

This active avidin-induced clearance of liposomes, or any other lipidic nanoparticle, from the circulation enables one to study critical aspects of MR molecular imaging, including targeting kinetics, the specificity of signal changes as well as vascular leakage and permeability.

Paramagnetic and fluorescent PEGylated micelles

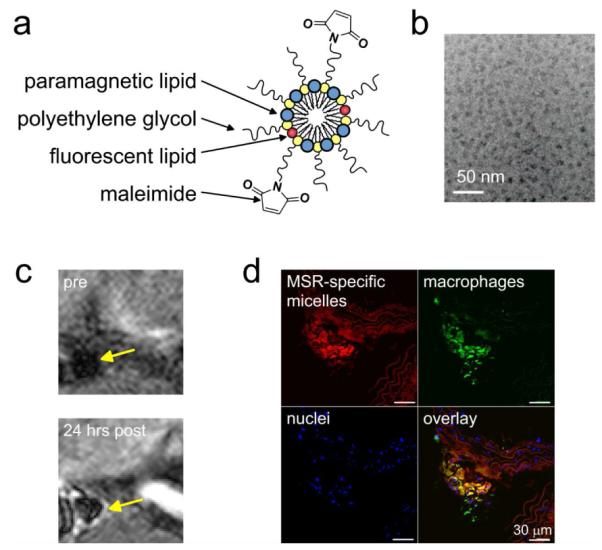

Micelles composed of PEGylated lipids, have been recognized to be particularly interesting for carrying poorly soluble pharmaceutical agents18. We used this platform to create paramagnetic and fluorescent micelles by mixing a PEGylated lipid and the paramagnetic lipid Gd-DTPA-distearyl amide in a 1 to 1 ratio with a small fraction of a fluorescent lipid.34 In Figure 4a a schematic representation of this contrast agent is depicted which also exposes maleimide moieties to enable functionalization. The size and morphology of this nanoparticle was investigated with cryo-TEM and indicated its diameter to be around 15 nm (Figure 4b). This relatively small size makes this nanoparticle particularly interesting for molecular imaging of extravascular targets, since it can penetrate a dysfunctional endothelial barrier, associated with pathologies like cancer and atherosclerosis.

Figure 4. Paramagentic and fluorescent PEGylated micelles.

(a) Schematic representation of the micellar contrast agent. (b) Cryo-TEM reveals small structures. (c) High resolution T1-weighted MR images before and 24 hours after administration of macrophage scavenger receptor specific micelles revealed pronounced signal enhancement in the lesioned aortic wall of an apoE-KO mouse. (d) Fluorescence microscopy of a DAPI colored (to stain nuclei) plaque section showed uptake of the rhodamine labeled micelles by macrophages (green). Reproduced with permission from ref34.

The bimodal PEG-micelles have been employed for molecular imaging of macrophages in atherosclerosis. It was shown that 24 hours post intravenous administration the vessel wall of apoE-KO mice was pronouncedly enhanced on MRI images (Figure 4c) for the macrophage scavenger receptor specific micelles only. Because of the dual labeling of the micelles immunofluorescence could be used to reveal the predominant macrophage association of the MSR-targeted micelles (Figure 4d). Recently, Briley-Saebo et al. applied this agent to identify and visualize oxidation-rich atherosclerotic lesions in apoE-KO mice35.

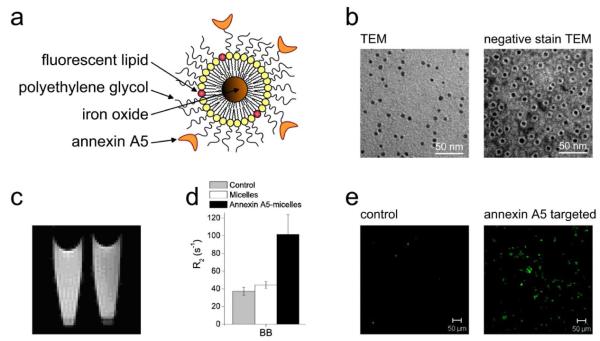

Iron oxide micelles

Iron oxide nanoparticles that are synthesized in nonpolar organic solvents can be incorporated into the core of micelles formed from PEGylated lipids26. Functionalization of such nanoparticles can be easily realized through use of these reactive PEG-lipids and subsequent conjugation with ligand. Furthermore, fluorescent properties can be introduced by the inclusion of fluorescent dyes (Figure 5a). TEM and negative staining TEM revealed that it is possible to produce mono-disperse particles that are covered by a monolayer of lipids. We used this platform for the detection of apoptotic cells by conjugating Annexin A5, a protein that has high affinity for phosphatidyl serine, a phospholipid exposed in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane of apoptotic cells36. These Annexin A5 conjugated particles showed high affinity for apoptotic cells, which resulted in a large decrease of T2 of a pellet of these cells, and consequently a darkening of the T2-weighted MR images of the cell pellet (Figure 5c). The transverse relaxation rates R2 (1/T2) of non-treated apoptotic cells as well as apoptotic cells incubated with non-specific nanoparticles remained unaffected (Figure 5d). The inclusion of a fluorescent amphiphile allowed corroborating these MRI findings with fluorescence microscopy (Figure 5e). In vivo, this contrast agent might be very useful for detecting apoptotic cells in pathological processes such as ischemia reperfusion injury, atherosclerosis, and tumor treatment.

Figure 5. Imaging apoptosis with micellar iron oxide.

(a) Schematic representation of the micellar iron oxide that contained fluorescent amphiphiles (red) and was functionalized with the apoptosis-specific protein Annexin A5. (b) TEM and negative staining TEM of micellar iron oxide. (c) On T2-weighted images, the uptake of the contrast agent resulted in a signal decrease of the pellet of cells that were incubated with Annexin A5 functionalized micellar iron oxide (right), as compared to control cells (left). (d) Quantitative analysis revealed a significant R2 increase for the Annexin A5 conjugated nanoparticles, while non-conjugated micelles had no such effect. (e) The specific binding of the agent with apoptotic cells was visualized with fluorescence microscopy. Reproduced with permission from ref26.

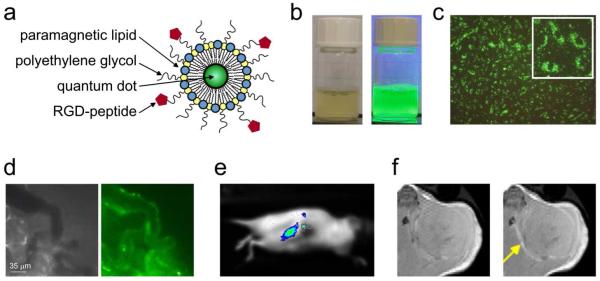

Paramagnetic quantum dot micelles

Mulder et al. created MRI-visible QD-micelles by incorporation of a paramagnetic amphiphile in the micellar coating.20,25 As above, the PEG chains of these micelles can be functionalized with targeting ligands. In Figure 6a a schematic of a RGD-peptide conjugated paramagnetic QD-micelle (pQD) is depicted. In Figure 6b the UV light-induced luminescence of this contrast agent can clearly be appreciated. The ionic relaxivity r1 of the QD-micelle at clinically relevant field strength of 1.41 T was more than 12 mM−1s−1, which is 3 times higher than that of Gd-DTPA at this field strength. Since the QD-micelles contain approximately 300 lipid molecules, half of which are Gd3+ chelating lipids (Gd-DTPA-DSA), the relaxivity per mM nanoparticle is estimated to be circa 2000 mM−1s−1. This high relaxivity makes the QD contrast agent an attractive candidate for molecular MRI purposes.

Figure 6. Paramagnetic QD-micelles for multimodality imaging.

(a) Schematic depiction of αvβ3-specific and paramagnetic QD-micelles. (b) Photograph of the QD-micelles in normal light (left) and under UV illumination (right). (c) Fluorescence microscopy of HUVEC incubated with αvβ3-specific and paramagnetic QD-micelles. (d) Intravital microscopy of microvessels in tumor-bearing mice after intravenous injection of RGD-pQDs. The brightfield (left) and the fluorescence image (right) revealed labeling of endothelial cells in tumor blood vessels. (e) Fluorescence image of a tumor bearing mouse following intravenous administration of the contrast agent, revealed tumor accumulation. (f) T1-weighted MR images before and 45 minutes after the injection of the αvβ3-specific and paramagnetic QD-micelles. Reproduced with permission from ref20.

The specificity of this contrast agent for proliferating endothelial cells in vitro was assessed with fluorescence microscopy. It was shown that the αvβ3-integrin specific particles were massively taken up (Figure 6c), to a much higher extent than the non-specific version (not shown). Targeted multimodality imaging of tumor angiogenesis was performed on tumor bearing mice that were intravenously injected with the contrast agent and were studied with either intravital microscopy, fluorescence imaging or MRI in vivo. Intravital microscopy was used for the real-time monitoring of the fate of injected QDs. In Figure 6d, a brightfield and a fluorescence image of tumor blood vessels are depicted 30 minutes after injection. Fluorescence imaging enabled the visualization of particle accumulation with high sensitivity and high temporal resolution in mice that grew a tumor in their kidney (Figure 6e). High resolution T1-weighted MRI was performed before and 45 minutes following RGD-conjugated QD-micelle administration and revealed significant signal enhancement that was mainly found at the tumor periphery (Figure 6f), which corresponds with the regions of the tumor with highest angiogenic activity.

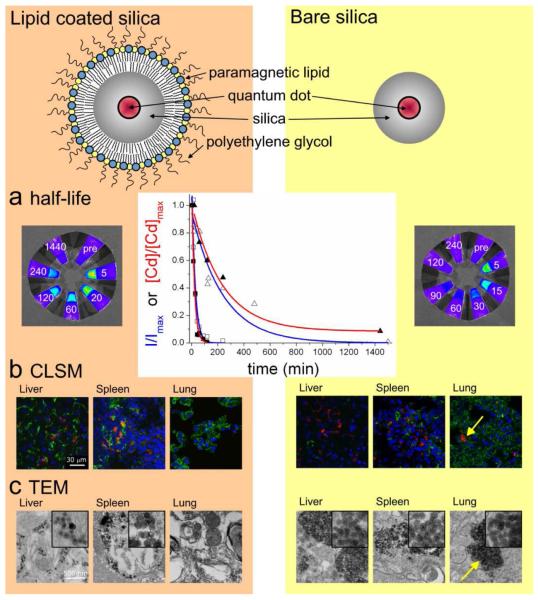

Lipid-coated silica nanoparticles

In the past decade, silica-based nanoparticles have increasingly been exploited for biomedical applications, including drug and gene delivery, and as a carrier vehicle for different contrast generating materials37,38. Interestingly, the ease of incorporation of different chemicals in silica makes it an excellent material for the integration of multiple diagnostically active materials to enable multimodality biomedical imaging.

Despite the intrinsic utility of silica for biomedical applications, a surface coating has to be applied to make inorganic nanoparticles applicable for functionalization, for improved pharmacokinetics and to prevent the particles from aggregating. To address this issue we have recently developed a novel method to obtain hydrophobic silica nanoparticles coated with a physically adsorbed monolayer of PEGylated phospholipids (Figure 7, top)39. This highly flexible coating method allows, next to the inclusion of PEGylated lipids, the incorporation of many other lipid species, e.g. paramagnetic lipids for MRI and bio-functional lipids to achieve target-specificity. The cytotoxicity and pharmacokinetics of paramagnetic and PEG-lipid coated quantum dot containing silica nanoparticles was studied by van Schooneveld et al.40. A variety of imaging techniques were employed and the results were compared with those obtained with bare silica nanoparticles. Compared to bare silica, lipid-coated silica exhibited a prolonged circulation half-life as determined by both analytical chemical determination (ICP-MS) and quantitative fluorescence imaging of blood samples (Figure 7a). Confocal microscopy (Figure 7b) and TEM (Figure 7c) of tissue sections of mice sacrificed 24 hours after the administration of lipid-coated (left) and bare silica nanoparticles (right) revealed that both particles accumulate in (and clear via) the liver and spleen. Interestingly, the bare silica particles were also found to accumulate in the lungs of the animals. TEM investigations indicated this to be caused by the aggregation of the bare silica particles upon intravenous administration, a phenomenon that was not observed for the lipid-coated nanoparticles.

Figure 7. Pharmacokinetics of lipid-coated silica nanoparticles investigated with multimodality imaging.

Schematic depiction of quantum dot containing silica particle with (top, left) and without (top, right) a lipid coating. (a) Determination of blood circulation half-life values by fluorescence imaging (photographs, blue graphs) and ICP-MS (red graphs). The values were normalized to the maximum photon count (Imax) or maximum Cd concentration (Cdmax). (b) Confocal microscopy of sections from different organs collected from mice at 24 hrs after injection and stained for endothelial cells to visualize blood vessels (green) and nuclei (blue), shows particle accumulation in red. (c) TEM was used to show particle uptake by cells in the liver, spleen and lung. The lipid-coated silica particles were individually dispersed, while the bare silica particles were found to be aggregated and trapped in the capillary bed of the lungs (bottom, right). Reproduced with permission from ref40.

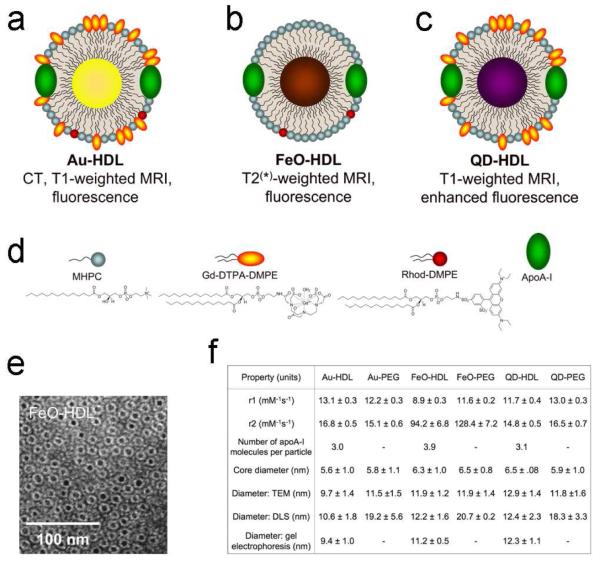

Nanocrystal core high-density lipoproteins

Endogenous nanoparticles such as lipoproteins and viruses have also been modified for use as bio-compatible multimodality contrast agents14,41. High-density lipoprotein (HDL), the smallest of the lipoprotein family, is known to migrate to atherosclerotic plaques and remove cholesterol from macrophages. This natural targeting mechanism of HDL was exploited by Frias et al. to develop a probe for molecular imaging of macrophages14. The particle was constituted from HDL apolipoproteins and phospholipids, with or without unesterified cholesterol. A paramagnetic phospholipid, Gd-DTPA-dimethyl-phosphoethanolamine, and a fluorescent phospholipid were incorporated for imaging purposes. This contrast agent was applied to a mouse model of atherosclerosis and showed strong MRI signal enhancement within the lesioned wall at 24 hours post injection.

Recently, Cormode et al. modified HDL particles to create endogenous nanoparticle-inorganic material composites (Figure 8a-c)42. In addition to modifying the phospholipid coating to provide contrast for medical imaging, as mentioned above, a method was developed to modify the hydrophobic core for the same purpose. The original hydrophobic core of HDL was replaced by different nanocrystals, i.e. gold nanoparticles, iron oxide nanoparticles and quantum dots to produce a broad range of novel contrast agents for multimodality imaging. Fluorescent and paramagnetic lipids were included in the phospholipid corona of the particles as appropriate (Figure 8d) so that all the nanocrystal HDL were at least MRI and fluorescence active and therefore multimodal. These particles were extensively characterized by negative staining TEM (Figure 8e) and relaxometry (Fgiure 8f), while protein analysis and other techniques found the nanoparticles to be very similar to native HDL (Figure 8f). The relaxometry data showed that the prepared HDL nanoparticles have acceptable MRI contrast generation abilities.

Figure 8. Nanocrystal core high density lipoprotein.

Schematic depiction of (a) Au-HDL, (b) FeO-HDL and (c) QD-HDL. (d) Different (functional) molecules that are employed in the HDL coating. (e) Negative stain TEM images of FeO-HDL. (f) Summary of the (physical) properties of nanocrystal HDL and PEG-coated control particles. Values are given as the mean ± the standard deviation. Reproduced with permission from ref42.

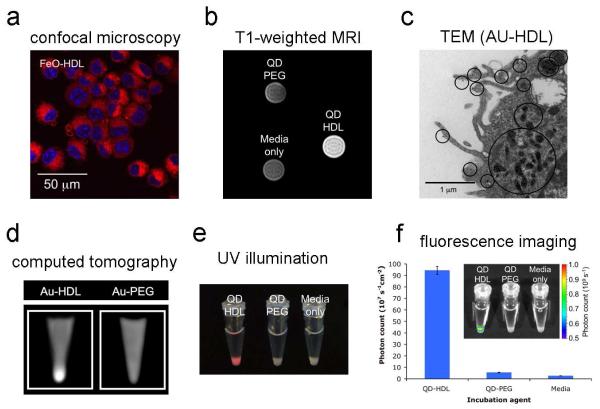

In vitro imaging experiments, of which examples are shown in Figure 9, revealed that these particles were abundantly taken up by macrophages, as evidenced by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Figure 9a), cell pellet MR imaging (Figure 9b) and TEM (Figure 9c). The macrophage uptake of Au-HDL was also demonstrated with CT imaging (Figure 9d), while the unique fluorescent properties of QD-HDL allowed the visualization (Figure 9e) and quantification of its uptake (Figure 9f), using optical techniques.

Figure 9. Uptake of nanocrystal HDL by macrophage cells in vitro.

(a) Confocal microscopy of cells incubated for 2 hours with FeO-HDL, which appear red (rhodamine) and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (b) T1-weighted MR image of pellets of cells incubated for 4 hrs with QD-HDL, QD-PEG, or cells that were left untreated. (c) TEM image where black circles indicate areas of Au-HDL uptake. (d) CT images of cell pellets incubated with Au-HDL and Au-PEG. (e) Photographs of pellets of cells incubated with QD-HDL, QD-PEG or control cells taken under UV irradiation. (f) Chart of fluorescence intensity of the cell pellets from (e), while the inset shows typical fluorescence images. Reproduced with permission from ref42.

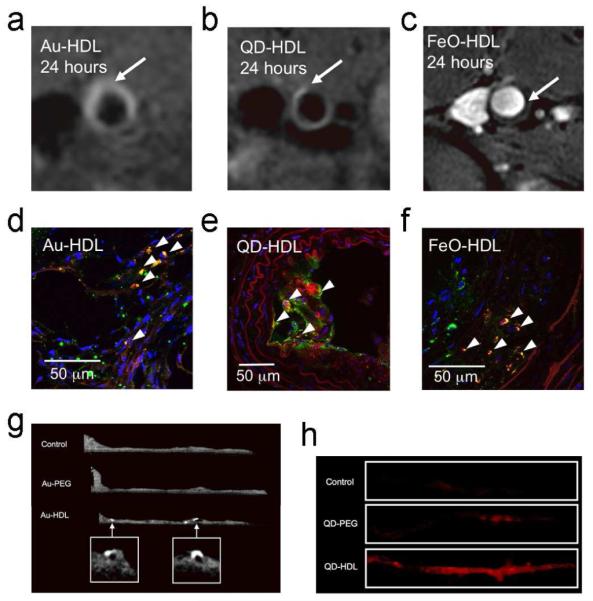

In vivo experiments using the imageable HDL nanoparticles were performed with the apolipoprotein E knockout (apoE-KO) mouse model of atherosclerosis (Figure 10). The abdominal aorta of mice injected with Au-HDL and QD-HDL appeared brighter on T1-weighted MR images at 24 hours (Figure 10a and b, respectively), while at this time point a signal decrease in the aortic wall was observed on T2*-weighted images for the FeO-HDL injected animals (Figure 10c). Confocal microscopy of aortic sections that were stained for macrophages (green) and for nuclei (blue) revealed the nanocrystal HDL particles (red) to be associated with macrophages, where the areas of co-localization appeared as orange/yellow (Figure 10d, e and f). Computed tomography images of aorta specimen from Au-HDL-injected and control animals revealed specific uptake of Au-HDL only (Figure 10g). Lastly, fluorescence imaging photographs of a control aorta, an aorta of a mouse injected with a non-specific QD-PEG nanoparticle and QD-HDL are displayed in Figure 10h. QD-HDL was massively taken up into the aorta wall, to a much greater extent than QD-PEG control particles.

Figure 10. Multimodality imaging of atherosclerosis using nanocrystal HDL.

T1-weighted MR images of the aorta of apoE-KO mice 24 hours post-injection with paramagnetic (a) Au-HDL or (b) QD-HDL particles. Arrows indicate areas enhanced in the post images. (c) T2*-weighted image of an apoE-KO mouse 24 hours post-injection with FeO-HDL. The arrow indicates a vessel wall region with hypo-intense signal. (d, e, f) Confocal microscopy images of aortic sections of mice injected with different nanocrystal HDL preparations. Red is nanocrystal HDL, macrophages are green and nuclei are shown in blue. Yellow indicates co-localization of nanocrystal HDL with macrophages and is indicated by arrowheads. (g) Ex vivo

Conclusions

In this account we have shown the possibilities to create different multimodality nanoparticles from amphiphilic molecules and diagnostically active materials. The nanoparticles span a wide range of properties in terms of size, morphology, detectability and target specificity. A variety of applications were explored in alive mice, including molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis and atherosclerosis. We have also shown that these supramolecular constructs allow a high degree of flexibility for functionalization. This may be exploited to introduce target-specificity, but also to manipulate contrast agent blood clearance kinetics using, among others, a so-called avidin-chase.

The multimodality characteristics of the different contrast agent platforms proofed to be extremely valuable for validation purposes and to understand mechanisms of particle-target-interaction at the anatomic, organ, cellular, and sub-cellular level. Additionally and importantly, we have shown the value of multimodality imaging to study the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of novel nanosized materials. One of the most exciting developments lies in combining synthetic materials with nature’s own nanoparticles as exemplified by the nanocrystal core HDL platform.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Partial support was provided by: NIH/NHLBI R01 HL71021, NIH/ NHLBI R01 HL78667 (ZAF) and the Peter Jay Sharp Foundation (WJMM). The research in the Eindhoven laboratory (GJS, GAFvT, KN) was funded in part by the BSIK program entitled Molecular Imaging of Ischemic Heart Disease (project number BSIK03033), the European Union-supported Network-of-Excellence entitled Diagnostic Molecular Imaging (DiMI; contract number: LSHB-CT-2005-512146), and was performed in the framework of the European Cooperation in the field of Scientific and Technical Research (COST) D38 Action Metal-Based Systems for Molecular Imaging Applications.

Biography

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

Willem J. M. Mulder studied chemistry at the Utrecht University (the Netherlands) and obtained his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering at the Eindhoven University of Technology (the Netherlands) in 2006. He currently holds an assistant professorship of radiology at the Translational and Molecular Imaging Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York. He heads the Nanomedicine Program, which focuses on the development of novel nanoparticles for multimodality biomedical applications.

Gustav J. Strijkers is associate professor of biomedical MRI at the Eindhoven University of Technology (the Netherlands). He obtained a Ph.D. (1999) in applied physics from the Eindhoven University of Technology. In 2000 he was a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the Johns Hopkins University. During the last eight years he has focused on the physics and biomedical applications of magnetic resonance imaging and molecular imaging.

Geralda A. F. van Tilborg obtained a Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering at Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands in 2008. Currently she holds a postdoctoral fellowship at the Image Science Institute, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands.

David P. Cormode received his Ph.D. in chemistry at Oxford University. He currently holds a postdoctoral fellowship Translational and Molecular Imaging Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York Zahi A. Fayad is professor of radiology and medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. Today, he directs the Translational and Molecular Imaging Institute at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. His current research is in the development of multimodality imaging to study cardiovascular disease.

Klaas Nicolay is professor of biomedical NMR at Eindhoven University of Technology (the Netherlands). He received a Ph.D. in biophysical chemistry from Groningen University in 1983. Since 2001 he directs the Biomedical NMR group within the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Eindhoven University of Technology. Dr. Nicolay’s prime research interests are the development of non-invasive MR-based techniques to enable functional and molecular imaging of the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems, as well as on cancer.

REFERENCES

- (1).Mulder WJ, Cormode DP, Hak S, Lobatto ME, Silvera S, Fayad ZA. Multimodality Nanotracers for Cardiovascular Applications. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2008;5(Suppl 2):S103–S111. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sanhai WR, Sakamoto JH, Canady R, Ferrari M. Seven Challenges for Nanomedicine. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008;3:242–244. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Weissleder R, Mahmood U. Molecular Imaging. Radiology. 2001;219:316–333. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma19316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Mulder WJ, Strijkers GJ, van Tilborg GA, Griffioen AW, Nicolay K. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Contrast-Enhanced MRI and Molecular Imaging. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:142–164. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Liu Y, Miyoshi H, Nakamura M. Nanomedicine for Drug Delivery and Imaging: a Promising Avenue for Cancer Therapy and Diagnosis Using Targeted Functional Nanoparticles. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120:2527–2537. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bulte JW, Kraitchman DL. Iron Oxide MR Contrast Agents for Molecular and Cellular Imaging. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:484–499. doi: 10.1002/nbm.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Liao H, Nehl CL, Hafner JH. Biomedical Applications of Plasmon Resonant Metal Nanoparticles. Nanomed. 2006;1:201–208. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hilger I, Hiergeist R, Hergt R, Winnefeld K, Schubert H, Kaiser WA. Thermal Ablation of Tumors Using Magnetic Nanoparticles: an in Vivo Feasibility Study. Invest Radiol. 2002;37:580–586. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Qian X, Peng XH, Ansari DO, Yin-Goen Q, Chen GZ, Shin DM, Yang L, Young AN, Wang MD, Nie S. In Vivo Tumor Targeting and Spectroscopic Detection With Surface-Enhanced Raman Nanoparticle Tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).O’Neal DP, Hirsch LR, Halas NJ, Payne JD, West JL. Photo-Thermal Tumor Ablation in Mice Using Near Infrared-Absorbing Nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2004;209:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Quantum Dot Bioconjugates for Imaging, Labelling and Sensing. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:435–446. doi: 10.1038/nmat1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lee CC, MacKay JA, Frechet JM, Szoka FC. Designing Dendrimers for Biological Applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1517–1526. doi: 10.1038/nbt1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kay MA, Glorioso JC, Naldini L. Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy: the Art of Turning Infectious Agents into Vehicles of Therapeutics. Nat. Med. 2001;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Frias JC, Williams KJ, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Recombinant HDL-Like Nanoparticles: a Specific Contrast Agent for MRI of Atherosclerotic Plaques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16316–16317. doi: 10.1021/ja044911a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Huang X, Bronstein LM, Retrum J, Dufort C, Tsvetkova I, Aniagyei S, Stein B, Stucky G, McKenna B, Remmes N, Baxter D, Kao CC, Dragnea B. Self-Assembled Virus-Like Particles With Magnetic Cores. Nano. Lett. 2007;7:2407–2416. doi: 10.1021/nl071083l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers As an Emerging Platform for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Torchilin VP. Recent Advances With Liposomes As Pharmaceutical Carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:145–160. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Torchilin VP, Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Papahadjopoulos-Sternberg B. Immunomicelles: Targeted Pharmaceutical Carriers for Poorly Soluble Drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:6039–6044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bagwe RP, Kanicky JR, Palla BJ, Patanjali PK, Shah DO. Improved Drug Delivery Using Microemulsions: Rationale, Recent Progress, and New Horizons. Crit Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2001;18:77–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Mulder WJ, Koole R, Brandwijk RJ, Storm G, Chin PT, Strijkers GJ, de Mello DC, Nicolay K, Griffioen AW. Quantum Dots With a Paramagnetic Coating As a Bimodal Molecular Imaging Probe. Nano. Lett. 2006;6:1–6. doi: 10.1021/nl051935m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).van Schooneveld MM, Vucic E, Koole R, Zhou Y, Stocks J, Cormode DP, Tang CY, Gordon RE, Nicolay K, Meijerink A, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJ. Improved Biocompatibility and Pharmacokinetics of Silica Nanoparticles by Means of a Lipid Coating: A Multimodality Investigation. Nano. Lett. 2008;8:2517–2525. doi: 10.1021/nl801596a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Dubertret B, Skourides P, Norris DJ, Noireaux V, Brivanlou AH, Libchaber A. In Vivo Imaging of Quantum Dots Encapsulated in Phospholipid Micelles. Science. 2002;298:1759–1762. doi: 10.1126/science.1077194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Mulder WJ, Strijkers GJ, Griffioen AW, van Bloois L, Molema G, Storm G, Koning GA, Nicolay K. A Liposomal System for Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Molecular Targets. Bioconjug. Chem. 2004;15:799–806. doi: 10.1021/bc049949r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Vuu K, Xie J, McDonald MA, Bernardo M, Hunter F, Zhang Y, Li K, Bednarski M, Guccione S. Gadolinium-Rhodamine Nanoparticles for Cell Labeling and Tracking Via Magnetic Resonance and Optical Imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 2005;16:995–999. doi: 10.1021/bc050085z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).van Tilborg GA, Mulder WJ, Chin PT, Storm G, Reutelingsperger CP, Nicolay K, Strijkers GJ. Annexin A5-Conjugated Quantum Dots With a Paramagnetic Lipidic Coating for the Multimodal Detection of Apoptotic Cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2006;17:865–868. doi: 10.1021/bc0600463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).van Tilborg GA, Mulder WJ, Deckers N, Storm G, Reutelingsperger CP, Strijkers GJ, Nicolay K. Annexin A5-Functionalized Bimodal Lipid-Based Contrast Agents for the Detection of Apoptosis. Bioconjug. Chem. 2006;17:741–749. doi: 10.1021/bc0600259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Mandal SK, Lequeux N, Rotenberg B, Tramier M, Fattaccioli J, Bibette J, Dubertret B. Encapsulation of Magnetic and Fluorescent Nanoparticles in Emulsion Droplets. Langmuir. 2005;21:4175–4179. doi: 10.1021/la047025m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Storrs RW, Tropper FD, Li HY, Song CK, Kuniyoshi JK, Sipkins DA, Li KCP, Bednarski MD. Paramagnetic Polymerized Liposomes - Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications for Magnetic-Resonance-Imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1995;117:7301–7306. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Strijkers GJ, Mulder WJ, van Heeswijk RB, Frederik PM, Bomans P, Magusin PC, Nicolay K. Relaxivity of Liposomal Paramagnetic MRI Contrast Agents. MAGMA. 2005;18:186–192. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Mulder WJ, Strijkers GJ, Habets JW, Bleeker EJ, van der Schaft DW, Storm G, Koning GA, Griffioen AW, Nicolay K. MR Molecular Imaging and Fluorescence Microscopy for Identification of Activated Tumor Endothelium Using a Bimodal Lipidic Nanoparticle. FASEB J. 2005;19:2008–2010. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4145fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Mulder WJ, van der Schaft DW, Hautvast PA, Strijkers GJ, Koning GA, Storm G, Mayo KH, Griffioen AW, Nicolay K. Early in Vivo Assessment of Angiostatic Therapy Efficacy by Molecular MRI. FASEB J. 2007;21:378–383. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6791com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Iagaru A, Chen X, Gambhir SS. Molecular Imaging Can Accelerate Anti-Angiogenic Drug Development and Testing. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2007;4:556–557. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).van Tilborg GA, Strijkers GJ, Pouget EM, Reutelingsperger CP, Sommerdijk NA, Nicolay K, Mulder WJ. Kinetics of Avidin-Induced Clearance of Biotinylated Bimodal Liposomes for Improved MR Molecular Imaging. Magn Reson. Med. 2008;60:1444–1456. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mulder WJ, Strijkers GJ, Briley-Saboe KC, Frias JC, Aguinaldo JG, Vucic E, Amirbekian V, Tang C, Chin PT, Nicolay K, Fayad ZA. Molecular Imaging of Macrophages in Atherosclerotic Plaques Using Bimodal PEG-Micelles. Magn Reson. Med. 2007;58:1164–1170. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Briley-Saebo KC, Shaw PX, Mulder WJ, Choi SH, Vucic E, Aguinaldo JG, Witztum JL, Fuster V, Tsimikas S, Fayad ZA. Targeted Molecular Probes for Imaging Atherosclerotic Lesions With Magnetic Resonance Using Antibodies That Recognize Oxidation-Specific Epitopes. Circulation. 2008;117:3206–3215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.757120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Koopman G, Reutelingsperger CP, Kuijten GA, Keehnen RM, Pals ST, van Oers MH. Annexin V for Flow Cytometric Detection of Phosphatidylserine Expression on B Cells Undergoing Apoptosis. Blood. 1994;84:1415–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Rieter WJ, Kim JS, Taylor KM, An H, Lin W, Tarrant T, Lin W. Hybrid Silica Nanoparticles for Multimodal Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2007;46:3680–3682. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Roy I, Ohulchanskyy TY, Bharali DJ, Pudavar HE, Mistretta RA, Kaur N, Prasad PN. Optical Tracking of Organically Modified Silica Nanoparticles As DNA Carriers: a Nonviral, Nanomedicine Approach for Gene Delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:279–284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408039101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Koole R, van Schooneveld MM, Hilhorst J, Castermans K, Cormode DP, Strijkers GJ, de Mello DC, Vanmaekelbergh D, Griffioen AW, Nicolay K, Fayad ZA, Meijerink A, Mulder WJ. Paramagnetic Lipid-Coated Silica Nanoparticles With a Fluorescent Quantum Dot Core: a New Contrast Agent Platform for Multimodality Imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008;19:2471–2479. doi: 10.1021/bc800368x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).van Schooneveld MM, Vucic E, Koole R, Zhou Y, Stocks J, Cormode DP, Tang CY, Gordon RE, Nicolay K, Meijerink A, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJ. Improved Biocompatibility and Pharmacokinetics of Silica Nanoparticles by Means of a Lipid Coating: a Multimodality Investigation. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2517–2525. doi: 10.1021/nl801596a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Anderson EA, Isaacman S, Peabody DS, Wang EY, Canary JW, Kirshenbaum K. Viral Nanoparticles Donning a Paramagnetic Coat: Conjugation of MRI Contrast Agents to the MS2 Capsid. Nano. Lett. 2006;6:1160–1164. doi: 10.1021/nl060378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Cormode DP, Skajaa T, van Schooneveld MM, Koole R, Jarzyna P, Lobatto ME, Calcagno C, Barazza A, Gordon RE, Zanzonico P, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJ. Nanocrystal Core High-Density Lipoproteins: a Multimodality Contrast Agent Platform. Nano Lett. 2008;8:3715–3723. doi: 10.1021/nl801958b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]