Abstract

Background

Extremely few objective estimates of traumatic brain injury incidence include all ages, both sexes, all injury mechanisms, and the full spectrum from very mild to fatal events.

Methods

We used unique Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records-linkage resources, including highly sensitive and specific diagnostic coding, to identify all Olmsted County, MN, residents with diagnoses suggestive of traumatic brain injury regardless of age, setting, insurance, or injury mechanism. Provider-linked medical records for a 16% random sample were reviewed for confirmation as definite, probable, possible (symptomatic), or no traumatic brain injury. We estimated incidence per 100,000 person-years for 1987–2000 and compared these record-review rates with rates obtained using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data-systems approach. For the latter, we identified all Olmsted County residents with any CDC-specified diagnosis codes recorded on hospital/emergency department administrative claims or death certificates 1987–2000.

Results

Of sampled individuals, 1257 met record-review criteria for incident traumatic brain injury; 56% were ages 16–64 years, 56% were male, 53% were symptomatic. Mechanism, sex, and diagnostic certainty differed by age. The incidence rate per 100,000 person-years was 558 (95% confidence interval = 528–590) versus 341 (331–350) using the CDC data system approach. The CDC approach captured only 40% of record-review cases. Seventy-four percent of missing cases presented to hospital/emergency department; none had CDC-specified codes assigned on hospital/emergency department administrative claims or death certificates; 66% were symptomatic.

Conclusions

Capture of symptomatic traumatic brain injuries requires a wider range of diagnosis codes, plus sampling strategies to avoid high rates of false-positive events.

Traumatic brain injury contributes to premature death, disability, and adverse medical, social, and financial consequences for the injured persons, their families, and society.1-6 Complete and valid estimates of brain injuries are essential for targeting prevention, predicting outcomes, addressing future care needs, identifying best practices, and implementing cost-effective treatments.3,7 Population-based objective estimates are needed that include both sexes, all age groups, all mechanisms of injury, and the full spectrum of injury, ranging from very mild (ie, no evident loss of consciousness or amnesia) to fatal events.

With rare exception,2,8-10 population-based objective estimates of traumatic brain injury employ approaches similar to the data-systems approach recommended for multi-state surveillance by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).11,12 While this approach has provided invaluable estimates of the burden of traumatic brain injury within the United States, it has several limitations. Case ascertainment relies on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) and ICD-9-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes (Table 1) as obtained from death certificates or from hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, or emergency department administrative claims.6,7,13 Non-fatal events diagnosed and managed outside hospital/emergency department settings are excluded; the number of such events is substantial and increasing.2,3,14-16 Even if office visits are included,2 a substantial proportion of traumatic brain injuries are likely missed by reliance on data collected for billing rather than clinical purposes (ie, administrative claims). Unless relevant for reimbursement, traumatic brain injury may not be coded (eg, polytrauma cases).3,15 Signs and symptoms are also under-represented.17 If signs and symptoms that constitute case status in most clinical definitions of traumatic brain injury are present in administrative data,6,18,19 they may be assigned ICD-9-CM codes, such as post-concussion syndrome (310.2), confusion (298.9), or late effects of injury (905.0, 907.0) in survivors, all absent from Table 1. Also excluded are events with evidence of brain injury in the medical record but assigned a code for fracture of face bones (802), other open wound of head (873), dislocation of jaw (830), injury to blood vessels of head and neck (900), crushing injury of face and scalp (925.1), etc.9 CDC-recommended codes are not only limited, they are biased toward more severe events. It is estimated that 70%–90% of all traumatic brain injuries are mild.16,19,20 While most persons who suffer mild traumatic brain injury experience full recovery, the potential for long-lasting neuropsychological impairment is increasingly demonstrated; there is rising concern, especially with injuries for which the only evidence of brain involvement is post-concussive symptoms.19-27 A wider range of diagnostic codes for identifying potential cases is essential for ensuring capture of all traumatic brain injuries. However, simple expansion of codes to include all relevant symptoms, late effects, and related injuries would produce unacceptable false-positive rates. There is also the potential for duplicate counting of traumatic brain injury events with the CDC data-systems approach. With some exceptions,28 multiple sources of diagnosis codes (eg, emergency department, hospital, death certificates) are sampled and merged, and unique persons are not identified — thus limiting the capacity to distinguish incident from subsequent events and sequelae.

TABLE 1.

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)13 diagnosis codes recommended by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention6 for identifying traumatic brain injury events from hospital or emergency department discharge data and death certificate data.

| ICD-9-CM Codesa | Description |

| Initially recommended for use, regardless of survival status | |

| 800.0-801.9 | Fracture of vault or base of the skull |

| 803.0-804.9 | Other and unqualified and multiple fractures of the skull |

| 850 | Concussion |

| 851 | Cerebral laceration and contusion |

| 852 | Subarachnoid/ subdural, extradural hemorrhage after injury |

| 853 | Other/ unspecified intracranial hemorrhage after injury |

| 854 | Intracranial injury of other and unspecified nature |

| Subsequently recommended for inclusion, regardless of survival statusc | |

| 950.1-950.3 | Injury to the optic chiasm, optic pathways, or visual cortex |

| 959.01 | Head injury, unspecified |

| 995.55 | Shaken Infant Syndrome |

| Recommended for inclusion, but only for fatal events identified from death certificates | |

| 873.0-873.9 | Other open wound of head |

| 905.0 | Late effect of fracture of skull and face bones |

| 907.0 | Late effect of intracranial injury without mention of skull fracture |

The present study addresses a number of limitations of previous estimates of traumatic brain injury incidence by taking advantage of the unique Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records-linkage resources. Rochester Epidemiology Project resources include a sensitive and specific diagnostic coding system and access to complete clinical details contained within provider-linked medical records for essentially every member of the geographically defined population.29 The study also compares incidence rates and patient characteristics using Rochester Epidemiology Project resources with those obtained for the same population using the CDC data-systems approach.

METHODS

Study Setting

Olmsted County, Minnesota (2000 census population, n=124,277) provides a unique opportunity for investigating the natural history of traumatic brain injury.30-35 Rochester, the county seat, is approximately 80 miles from the nearest major metropolitan area and home to one of the world’s largest medical centers, Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic and its 2 hospitals, together with Olmsted Medical Center (a second group practice and its hospital), provide nearly all of the medical care delivered to local residents. Since 1907, every Mayo patient has been assigned a unique identifier, and all information from every contact (including office, nursing home, hospital inpatient/outpatient, and emergency department visits) is contained within a unit record for each patient. Detailed information includes medical history, all clinical assessments, consultation reports, surgical procedures, discharge summaries, laboratory and radiology results, correspondence, death certificates, and autopsy reports. Diagnoses assigned at each visit are coded and entered into continuously updated computer files. The coding system was developed by Mayo for clinical, not billing, purposes and uses a 9 digit modification of the Hospital Adaptation of ICDA36 that affords high sensitivity and specificity (eAppendix 1, http://links.lww.com). Under auspices of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, the diagnostic index and medical records-linkage were expanded to include the other providers of medical care to local residents, including Olmsted Medical Center and the few private practitioners in the area. >The Rochester Epidemiology Project provides the capability for population-based studies of disease risk factors, incidence, and outcomes that is unique in the United States.29

Study Population

This study was approved by Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards. The medical records of individuals were not reviewed at any site for which the patients refused authorization for their records to be used for research.37-39

Incidence Using the Rochester Epidemiology Project Records-linkage Approach

The Rochester Epidemiology Project diagnostic index was used to construct a list of potential cases consisting of all Olmsted County residents with any diagnosis suggestive of head injury or traumatic brain injury (eAppendix 1, http://links.lww.com) from 1 January 1985 through 31 December 1999 (n = 45,791). The record review required to identify, confirm, and characterize incident events was extremely labor-intensive. Thus, a 20% random sample was identified for review. Due to budget and time constraints, the random review was completed on 7175 persons (16%). Trained nurse abstractors conducted the review under direction of a board-certified physiatrist (AB) and neuropsychologist (JM). The review involved all available clinical data, including, but not limited to, general history notes, emergency department notes, hospital records, radiological imaging findings, surgical records, and autopsy reports.

Traumatic brain injury was defined as a traumatically induced injury that contributed to physiological disruption of brain function. Incident events were defined as the first event during the study period among Olmsted County residents with no mention in the medical record of earlier traumatic brain injury. Each incident event was categorized as definite, probable, or possible using the Mayo Traumatic Brain Injury Classification System (eAppendix 2, http://links.lww.com).40 The system capitalizes on the strength of evidence of brain injury available within the medical record. Definite cases were those with evidence of either death due to this traumatic brain injury; loss of consciousness for at least 30 minutes; post-traumatic anterograde amnesia lasting at least 24 hours; a Glasgow Coma Scale full score in first 24 hours of <13 (unless invalidated upon review, eg, attributable to intoxication, sedation, systemic shock); or any of the following: intracerebral, subdural, or epidural hematoma; cerebral or hemorrhagic contusion; penetrating traumatic brain injury (dura penetrated); or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Probable cases lacked criteria for definite but had evidence of some loss of consciousness (momentary to <30 minutes); post-traumatic anterograde amnesia (momentary to <24 hours); or depressed, basilar or linear skull fracture (dura intact). Possible (symptomatic) traumatic brain injury cases lacked criteria for either definite or probable but had evidence of any of the following symptoms that lasted ≥30 minutes and were not attributable to pre-existing or comorbid conditions: blurred vision, confusion (mental state changes), dazed, dizziness, focal neurologic symptoms, headache, or nausea. Each confirmed incident event was also characterized as to mechanism of injury.

Incidence Using Our Application of the CDC Data-Systems Approach

We also estimated Olmsted County incidence rates employing the CDC approach that relies on ICD-9-CM codes obtained from death certificate and hospital or emergency department administrative data.6 As a consequence of the unique circumstances described above, more than 98% of all hospital or emergency department encounters by Olmsted County residents occur at the 3 Mayo Clinic – and Olmsted Medical Center – affiliated hospitals. Through a data-sharing agreement signed by Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, patient-level administrative data on healthcare utilization at these institutions are shared and archived within the Olmsted County Healthcare Expenditure and Utilization Database for use in approved research studies. Persons are consistently identified across institutions and over time. Data are electronically linked, affording complete information on all hospital and ambulatory care delivered by these providers to area residents from 1 January 1987 through the present. The database includes information from all encounters, regardless of patient age, payer, or insurance coverage. Hospitalization variables include patient’s unique identifier, sex, birth date, county of residence, admission type (inpatient/outpatient/emergency department), admission/discharge dates, discharge status, and ICD-9-CM codes for principal discharge diagnosis and up to 14 secondary diagnoses.41 Consistent with the CDC approach, we identified all Olmsted County residents with any relevant Table 1 code recorded in either hospital/emergency department administrative claims or death certificate data. We included the additional code 959.01 recommended for use by CDC for identifying mild traumatic brain injury.19 To provide comparable definitions of incidence for the record-review and CDC approaches, we limited the CDC-approach analysis to the earliest relevant traumatic brain injury code assigned to each person over the entire time frame.

The review of medical records that was required to estimate sensitivity and positive-predictive values of our application of the CDC data-systems approach was beyond the scope of the present study. However, we compared characteristics of record-review-identified traumatic brain injury cases with those captured and those missed using the CDC approach by identifying the subset of record-review cases with any hospital or emergency department encounter within 2 weeks before or 4 weeks after their traumatic brain injury and the further subset assigned any CDC-recommended ICD code in administrative claims or death certificates, plus remaining record-review cases who died within 1 year of injury with any CDC-recommended code for traumatic brain injury on their death certificate.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical data were summarized using means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies or percentages for categorical variables. In calculating traumatic brain injury incidence rates, the entire Olmsted County population was considered at risk. Denominator age- and sex-specific person-years were estimated from decennial census data with linear interpolation between census years and extrapolation from 2000 to 2006.42 Assuming that risk of traumatic brain injury for any individual is approximately constant over intervals defined in the underlying rate table (eg, 1 year), the likelihood is equivalent to a Poisson regression, which allowed us to use standard software to estimate standard errors and calculate 95% confidence intervals.43 We compared incidence rates between groups using the rate ratio test, as described by Lehmann and Romano.44

RESULTS

Incidence Using the Rochester Epidemiology Project Record-review Approach

There were 46,114 Olmsted County residents with any diagnosis code suggestive of traumatic brain injury from 1985 to 2000. The 323 who refused authorization at all Rochester Epidemiology Project providers where seen were excluded. From the remaining 45,791, a 16% sample was randomly selected for review of authorized medical records. Among all 7175 potential cases, 1429 individuals met record-review criteria for first episode of clinically-recognized traumatic brain injury from 1 January 1985 through 31 December1999. Because administrative claims for Olmsted County residents are available electronically only since 1987, to afford comparison between the record-review approach and the CDC approach, the present study was limited to 1 January 1987 through 31 December 1999. Characteristics of the 1257 people who met record-review criteria during that time frame are provided in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Olmsted County residents who met Rochester Epidemiology Project record-review criteria for traumatic brain injury, 1 January 1987–31 December 1999.

| Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject Characteristics | <16 | 16–64 | 65+ | All Ages |

| Numbera | (n=446) | (n=698) | (n=113) | (n=1257) |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Male | 286 (64) | 371 (53) | 41 (36) | 698 (56) |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| Fall | 170 (34) | 134 (17) | 97 (72) | 401 (28) |

| Motor vehicle accident | 29 (6) | 334 (42) | 25 (18) | 388 (27) |

| Hit by object | 17 (3) | 66 (8) | 4 (3) | 87 (6) |

| Assault/gunshot | 17 (3) | 72 (9) | 2 (2) | 91 (6) |

| Sports/recreation | 227 (45) | 127 (16) | 1 (1) | 355 (25) |

| Other | 48 (10) | 57 (7) | 6 (4) | 111 (8) |

| Classification by Evidence of Brain Injury: | ||||

| Definite | 20 (4) | 58 (8) | 27 (24) | 105 (8) |

| Probable | 153 (34) | 286 (41) | 44 (39) | 483 (38) |

| Possible (symptomatic) | 273 (61) | 354 (51) | 42 (37) | 669 (53) |

The number of persons who were included in the 16% random sample of all 45,791 potential cases from 1 January 1985 through 31 December 1999 and who then, following detailed medical record review, were confirmed as having met REP criteria for definite, probable or possible incident TBI from 1 January 1987 through 31 December 1999.

The broadest age category, ie, non-elderly adults (ages 16–64 years), accounted for over half of traumatic brain injury cases. The sex distribution differed by age; males accounted for 64% of cases among youth but only 36% among elderly adults. The most frequent mechanisms of injury among youth were sports/recreation among non-elderly adults, motor vehicle accidents; and among elderly adults, falls. Fewer than 10% of all confirmed cases met criteria for definite traumatic brain injury, as defined above (see eAppendix 2, http://links.lww.com). The distribution again differed by age; definite cases accounted for only 4% of cases among youth and 24% among elderly adults. Importantly, over half of all confirmed traumatic brain injury cases met criteria on the basis of symptoms alone.

Incidence rates and 95% confidence interval estimates using the record-review approach are provided in Table 3. Age groups varied by sex and evidence category. Overall (all evidence categories and both sexes combined), incidence rates were higher for youth compared with both non-elderly (p < 0.001) and elderly (p < 0.001) adults. For probable and possible cases (both sexes combined), rates were also higher for youth compared with non-elderly (p = 0.002 for probable, <0.001 for possible) and elderly (p = 0.04 for probable, <0.001 for possible) adults. By contrast, among definite cases, rates were higher for elderly adults compared with both non-elderly adults (p < 0.001) and youth (p < 0.001). Among women, when comparing youth with non-elderly adults, rates for youth were higher for all evidence categories combined (p = 0.005) and for probable cases (p = 0.04); when comparing youth with elderly adults, rates for youth were higher for possible cases (p = 0.03) but lower for definite cases (p = 0.03). Among men, when comparing youth with non-elderly adults, rates for youth were higher for all evidence categories combined (p < 0.001) and for probable (p = 0.04) and possible (p < 0.001) cases; when comparing youth with elderly adults, rates for youth were higher for all evidence categories combined (p < 0.001) and for probable (p = 0.03) and possible (p < 0.001) cases, but lower for definite cases (p = 0.002).

TABLE 3.

Incidence of traumatic brain injury per 100,000 person-yearsa among residents of Olmsted County, 1/1/1987–12/31/1999, using Rochester Epidemiology Project criteria.

| a. All Cases | Estimated Total events in Olmsted Countya |

Total Olmsted County Person-years |

Both sexes | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. | Incidence (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | |

| All ages (years) | 8,022 | 1,436,529 | 558 (528-590) | 482 (443-523) | 640 (593-689) |

| <16 | 2,846 | 360,120 | 790 (719-867) | 583 (496-680) | 987 (876-1,108) |

| 16–64 | 4,454 | 927,640 | 480 (445-517) | 440 (393-490) | 522 (470-578) |

| 65+ | 721 | 148,769 | 485 (399-583) | 506 (396-638) | 451 (323-611) |

| b. Definite | |||||

| All ages (years) | 670 | 1,436,529 | 47 (38-57) | 38 (28-51) | 56 (43-72) |

| < 16 | 128 | 360,120 | 35 (22-55) | 36 (18-67) | 35 (17-64) |

| 16-64 | 370 | 927,640 | 40 (30-52) | 27 (16-42) | 54 (38-73) |

| 65+ | 172 | 148,769 | 116 (76-168) | 99 (54-165) | 143 (76-244) |

| c. Probable | |||||

| All ages (years) | 3,082 | 1,436,529 | 215 (196-234) | 153 (132-178) | 280 (249-313) |

| <16 | 976 | 360,120 | 271 (230-318) | 193 (145-252) | 345 (281-420) |

| 16-64 | 1,825 | 927,640 | 197 (175-221) | 133 (108-162) | 263 (227-304) |

| 65+ | 281 | 148,769 | 189 (137-253) | 183 (119-268) | 198 (117-313) |

| d. Possible (Symptomatic) | |||||

| All ages (years) | 4,269 | 1,436,529 | 297 (275-320) | 290 (260-323) | 304 (272-339) |

| <16 | 1,742 | 360,120 | 484 (428-545) | 353 (286-431) | 607 (521-704) |

| 16-64 | 2,259 | 927,640 | 244 (219-270) | 280 (243-320) | 206 (174-242) |

| 65+ | 268 | 148,769 | 180 (130-244) | 225 (154-318) | 110 (52.7-202) |

Rates reflect the 1,257 Rochester Epidemiology Project confirmed traumatic brain injury incident cases identified from the random sample of all potential cases and then multiplying by 6.38 to account for the sampling.

Comparisons of record-review incidence rates between the sexes varied by age group and evidence category. For all age groups combined, males had higher rates than females for all evidence categories combined (p < 0.001) and for probable cases (p < 0.001). Among youth, men had higher rates than women for all evidence categories combined and for probable and possible cases (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Among non-elderly adults, men had higher rates than women for all evidence categories combined (p = 0.03) and for definite (p = 0.02) and probable (p < 0.001) cases. By contrast, among non-elderly adult possible cases, men had lower rates than women (p = 0.005). Among elderly adults, no statistically significant between-sex differences were observed (p values for all evidence categories combined, definite, probable, and possible cases = 0.62, 0.44, 0.91, 0.06 respectively).

Incidence Using the CDC Data-Systems Approach

From 1987 through 1999, 4894 Olmsted County residents either died with any relevant Table 1 codes for traumatic brain injury on their death certificate or were admitted to hospital/emergency department with any relevant Table 1 codes for traumatic brain injury (plus 959.01) in their administrative claims. Incidence rates using the CDC approach are provided in Table 4. Comparison of Table 4 rates with Table 3 rates reveals that the overall traumatic brain injury incidence obtained from applying the CDC data-systems approach was only 61% of that using the record-review approach. With the exception of elderly adult males, CDC rates were lower than record-review rates within each age- and sex-category. For both approaches, traumatic brain injury incidence rates were generally highest among youth and were higher among men than among women, especially for youth.

TABLE 4.

Incidence of traumatic brain injury per 100,000 person-yearsa among residents of Olmsted County, 1 January 198712 December 1999, using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)b diagnosis codes from hospital/emergency department discharge data or death certificate data, as recommended by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and including the additional CDC- recommended code for mild traumatic brain injuryc

| Female | Male | Both Sexes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Ages (years) | Incidence (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) |

| 279 (267-291) | 407 (392-422) | 341 (331-350) | |

| <16 | 462 (431-495) | 680 (643-719) | 574 (550-600) |

| 16-64 | 209 (196-222) | 302 (286-318) | 254 (244-265 ) |

| 65+ | 290 (256-327) | 350 (303-401) | 313 (285-343) |

Incidence rates were defined using the 1st relevant code assigned each unique person from 1 January 1987 through 31 December 1999. Persons for whom record review showed evidence of a previous traumatic brain injury that came to clinical attention were excluded as incident cases.

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, 3rd ed. (ICD-9-CM). Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1989.

Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, Coronado VG. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002–2006. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2010. Available online at http://wwwtest.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf

Characteristics of Rochester Epidemiology Project Record-review Cases Captured and Missed Using the CDC Data-systems Approach

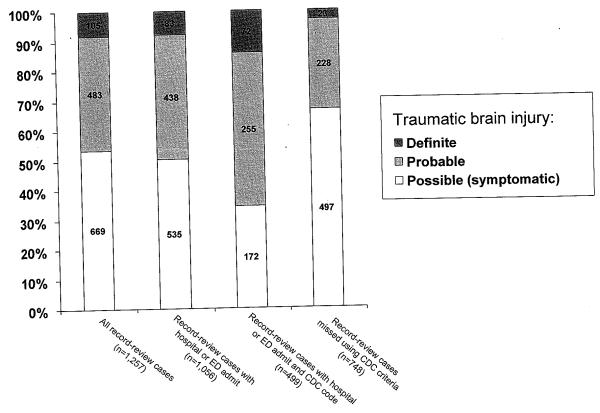

The Figure shows distributions by category for relevant subsets, with the distribution for all 1257 record-review traumatic brain injury incidence cases (Table 2) in the left column for comparative purposes. Of all record-review cases, 84% (1056/1257) experienced a hospital or emergency department admission within 2 weeks before through 4 weeks after injury; the distribution of this subset (second from left column) is similar to that for all record-review cases. Fewer than half of the 1056 (n = 499) had any CDC-recommended codes within the hospital or emergency department administrative claims or death certificates. Compared with all record-review cases, the severity distribution for these 499 (third from left column) reveals a greater percentage of definite cases and smaller percentage of possible (symptomatic) cases. An additional 10 record-review cases did not present to the hospital/emergency department but died within 1 year of injury with a CDC-recommended code on their death certificate. Thus, the total of all 1257 record-review cases captured using the CDC data-systems approach was 509, leaving 748 (60%) who were missed. Importantly, of the 748 missing cases, 74% were admitted to hospital/emergency department about the time of the injury. The right column reveals only 3% of missing cases were definite, 30% were probable, and 66% were possible (symptomatic).

FIGURE.

Distribution by level of evidence of physiologic disruption of brain function for a random sample of all Olmsted County residents who met Rochester Epidemiology Project record-review criteria for traumatic brain injury (n = 1257) (first column) and for specified subsets. Of all record-review cases, the 1056 (84%) with a hospital/emergency department (ED) admission within 2 weeks before to 4 weeks after the event are in the second column. Of the 1056 with such an encounter, the 499 (47%) with any International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)13 diagnosis code for traumatic brain injury consistent with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations6 in their relevant administrative claims or death certificates are in the third column. In addition to the 499, 10 record-review cases did not present to hospital or emergency department but died with a CDC-recommended code on their death certificate. The distribution of the remaining 748 record-review cases who would have been missed using the CDC data-systems approach recommendations are in the fourth column.

DISCUSSION

We used unique Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records-linkage resources to provide objective estimates of traumatic brain injury incidence for Olmsted County MN across the full spectrum of clinically-recognized disease. The incidence of 558/100,000 person-years using this approach was approximately 1.6 times the incidence of 339/100,000 person-years for the same population over the same time period using CDC-recommended ICD-9-CM codes recorded on death certificate or hospital and emergency department administrative-claims data. Importantly, 60% (n = 748) of all record-review-confirmed cases were missed using the CDC approach. Two-thirds of missing cases were possible (symptomatic). Of all 748 cases that were missed, 74% presented to hospital or emergency department at time of the traumatic brain injury but had no CDC-recommended codes on administrative claims or death certificate.

Other investigators report similar limitations of CDC-recommended ICD-9-CM codes for capturing all traumatic brain injury cases, and that limitations are greatest at the milder end of the spectrum.8,9,45-48 Bazarian et al. compared clinical assessment for mild traumatic brain injury with CDC-recommended diagnosis codes assigned at emergency department or hospital discharge.6,46 The specificity of CDC-recommended codes was 98%; however, sensitivity was only 46%. The authors concluded that mild traumatic brain injury incidence and prevalence estimates using these codes should be interpreted with caution.6,46 The situation does not improve following introduction of ICD-10 codes; Deb et al. found ICD-10 codes identified fewer than 50% of all head injury hospital admissions.49

Our incidence estimates using the CDC approach are lower than published national estimates from CDC.6 In our application of the CDC approach, we identified unique Olmsted County residents and used the earliest relevant code per individual over the full time period. This differs from CDC’s estimates, which are intended to include all unique events – not just the first event. While each approach is informative for different purposes, the capacity of the CDC data-systems approach for distinguishing multiple unique events from over-counting of the same event is limited with most state and national estimates. With the exception of some states,28 persons cannot be linked within claims data sources, sampling is conducted at the encounter level within each source, and samples are merged across sources.6,50 Over-counting is partially addressed by recommendations to exclude emergency department and hospital admissions that end in death or transfer; however, over-counting may still result from readmissions for the same event or discharge followed by out-of-hospital death.6,50,51 While studies suggest the proportions of inpatient readmissions and deaths following discharge for the same event are small,52,53 any such over-counting would exacerbate bias toward more severe events.

While CDC estimates typically exclude events identified and managed in physicians’ offices, Finkelstein et al.2 employed multiple data sources to include fatal and non-fatal events across all health care delivery settings. The authors addressed the potential for over-counting in the absence of unique identifiers with extensive strategies, some of which (eg, limiting the number of codes under consideration) could have contributed to undercounting. The incidence of 486/100,000 person-years reported by Finkelstein et al. was slightly lower than our record-review rate of 558/100,000 person-years. Our record review rates were very similar to the 540 traumatic brain injury events/100,000 population reported by Schootman et al.54 Schootman et al. included persons seen in physicians’ offices; however, they excluded persons who either died before being seen or were admitted as inpatients without being seen in the emergency department.54

The Rochester Epidemiology Project record-review approach to estimating traumatic brain injury incidence afforded several advantages over most previous studies. Similar to the study by Finkelstein et al.,2 our record-review estimates were population-based, including fatal and non-fatal events, both sexes, all age groups, all mechanisms of injury, and all health care settings. Our record-review approach differed from that by Finkelstein et al.2 and others in that potential cases were identified using a sensitive and specific 9-digit coding system developed for clinical rather than reimbursement purposes; the range of diagnostic codes was extremely broad. Traumatic brain injury case status among potential cases was confirmed by reviewing detailed provider-linked medical records and applying standardized criteria. Access to unique identifiers for all Olmsted County residents over the entire time period and across all Rochester Epidemiology Project providers afforded identification of true “incident” events.

Concerns regarding participation, recall, and prevalence bias that are inherent with survey studies were minimized. The proportion of potential cases excluded based on refusal of research authorization for use of medical records in research was 5.8% at Mayo for persons with a traumatic brain injury code assigned there and 3.8% at all Rochester Epidemiology Project providers where a traumatic brain injury code had been assigned; percentages were quite similar to those observed in 2 previous Rochester Epidemiology Project investigations of all Olmsted County residents assigned any diagnosis code.38,39 IRB approval for this study prohibited comparisons between refusers and non-refusers. However, such comparisons were possible with 1 of the 2 previous investigations, in which investigators obtained special IRB permission to compare characteristics of refusers and non-refusers in 1994–1996, before the requirement for authorization came into effect.38 That study, which was limited to persons seen at Mayo, found refusal rates were greater for persons younger than 60 years. Refusal rates were not associated with sex (p = 0.6), insurance type (p = 0.8), summary comorbidity (p = 0.6), or encounter frequency (p values for the number of office visits, likelihood of hospitalization, and likelihood of surgical procedure were 0.2, 0.6, and 0.4 respectively). When specific diagnoses were examined, the only difference between Olmsted County residents who did and did not refuse authorization at Mayo was a modest trend toward higher refusal rates for persons with prior diagnoses of mental disorders or circulatory disease.38,39

The present study has important limitations. The sample was drawn from a single geographic population, which in 1990 was 96% white. The age- and sex-distribution is similar to United States whites; however median income and education levels are higher.29 While no single geographic area is representative of all others, the under-representation of minorities and the fact that essentially all medical care is delivered by few providers compromises the generalizability of findings to other racial/ethnic groups and different health care environments.

The variability in published estimates of traumatic brain injury incidence is due in part to marked differences in case definition, especially for the category “mild”.16,20,21,45,55 Many investigations, including some earlier Rochester Epidemiology Project studies, required evidence of at least minimal loss of consciousness or post-traumatic amnesia to qualify as a case.30,31,35,56 The requirement minimizes the proportion of false-positive cases that some authors caution can occur because symptoms following head injury are inflated by patient expectations or comorbid stress.55,57 Estimates in the present study employed a categorization scheme that attempted to reduce confusion surrounding classification systems based on severity and instead reflected evidence of brain involvement; persons with loss of consciousness, post-traumatic amnesia, or skull fracture who failed to meet criteria for definite traumatic brain injury were categorized as probable. Individuals who failed to meet criteria for definite or probable but who presented for care following head injury with complaints of post-concussive symptoms (eg, dizziness, blurred vision, etc.) were included as possible traumatic brain injury. Persons with information suggesting the symptoms were associated with another condition were excluded; however, for people not excluded for these reasons, it is not possible to determine the extent to which our estimate of possible (symptomatic) cases was inflated by patient expectations. Our record-review and CDC incidence rates both excluded persons who did not seek medical attention.

Implications

Seventy-four percent of the record-review cases that were missed using the CDC data-systems approach had a hospital/emergency department encounter, although no CDC-recommended codes in hospital/emergency department administrative claims or death certificates. This observation can inform future efforts toward traumatic brain injury surveillance. Our finding suggests that proposals to expand traumatic brain injury surveillance to include office visits,2,3,15,19,45 while advisable, are not enough to capture the majority of cases that are missed using administrative data. Expansion of ICD codes beyond those in Table 1 is needed. Efforts to identify all potential cases with any suspect codes for head injuries, late effects, or relevant signs and symptoms would result in an unacceptable fraction of false-positive events; confirmation by record review would be untenable. This problem was addressed in our study by limiting the medical record review to a random sample of all potential cases within the Olmsted County population over the period of study and multiplying the proportion of confirmed cases observed in our sample to reflect rates of confirmed cases within the population. Even greater efficiencies could be achieved by stratified sampling based on pre-established positive predictive values for each code. National surveillance would also benefit by expanding the capacity to identify and follow unique individuals beyond certain states and selected sources to include all states and all sources (hospital, emergency department, office visits, and death certificates).

Our findings that elderly adults and youth were at highest risk for definite and possible traumatic brain injury, respectively, together with the generally higher risk for men observed by us and others, emphasize the need for greater understanding of patient-specific characteristics to reduce risk at the individual level. Our findings that non-elderly adults and possible events account for the greatest number of injuries emphasize the value of focusing on these age- and type-specific subgroups to reduce event rates at the population level. Possible (symptomatic) cases accounted for over half of all confirmed record-review cases and two-thirds of those missed using the CDC data-systems approach. These findings reinforce ongoing efforts by CDC and others toward increased recognition, especially within contact sports and the military, of injuries for which symptoms are the only available evidence of brain involvement.23,24,27 In light of increasing evidence of adverse outcomes following symptomatic events, the large numbers reported here also substantiate heightened concerns in the press and literature regarding implications, both at the individual and population level.21,58

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This research was supported by TBI Model System grants to Mayo Clinic from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (H133A020507, H133A070013) and a National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Health (Training Grant HD-07447). The study was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant Number R01 AG034676 from the National Institute on Aging).

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall KM, Karzmark P, Stevens M, Englander J, O’Hare P, Wright J. Family stressors in traumatic brain injury: a two-year follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:876–884. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelstein E, Corso PS, Miller TR. The Incidence and Economic Burden of Injuries in the United States. Oxford University Press; Oxford; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker-Collo SL, Feigin VL. Capturing the spectrum: suggested standards for conducting population-based traumatic brain injury incidence studies. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32:1–3. doi: 10.1159/000170084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed June 3, 2011];Injury Prevention & Control: Traumatic Brain Injury. http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/

- 5.Corrigan JD, Selassie AW, Orman JA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25:72–80. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181ccc8b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronado VG, Faul M, Wald MM, Xu L. [Accessed June 3, 2011];National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (U.S.) Division of Injury Response. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, 2002-2006. http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf.

- 7.Thurman DJ, Alverson C, Dunn KA, Guerrero J, Sniezek JE. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: a public health perspective. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14:602–615. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schootman M, Buchman TG, Lewis LM. National estimates of hospitalization charges for the acute care of traumatic brain injuries. Brain Inj. 2003;17:983–990. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000110427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryu WH, Feinstein A, Colantonio A, Streiner DL, Dawson DR. Early identification and incidence of mild TBI in Ontario. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36:429–435. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100007745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinlay A, Grace RC, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, Ridder EM, MacFarlane MR. Prevalence of traumatic brain injury among children, adolescents and young adults: prospective evidence from a birth cohort. Brain Inj. 2008;22:175–181. doi: 10.1080/02699050801888824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thurman DJ, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (U.S.) Guidelines for Surveillance of Central Nervous System Injury. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta, GA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thurman DJ, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (U.S.) [Accessed June 3, 2011];Division of Acute Care Rehabilitation Research and Disability Prevention. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: A Report to Congress. http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/tbi_congress/TBI_in_the_US.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service . The International Classification of Diseases-9th Revision-Clinical Modification: ICD-9-CM. 3rd ed U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fife D. Head injury with and without hospital admission: comparisons of incidence and short-term disability. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:810–812. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.7.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sosin DM, Sniezek JE, Thurman DJ. Incidence of mild and moderate brain injury in the United States, 1991. Brain Inj. 1996;10:47–54. doi: 10.1080/026990596124719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Peloso PM, Borg J, von Holst H, Holm L, Kraus J, Coronado VG, WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Incidence, risk factors and prevention of mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Rehabil Med. 2004:28–60. doi: 10.1080/16501960410023732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. [Accessed June 3, 2011];Department of Health and Human Services. ICD-9-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting, Effective October 1, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd9/icdguide09.pdf.

- 18.The Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee of the Head Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8:86–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (U.S.) [Accessed June 3, 2011];Report to Congress on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Steps to Prevent a Serious Public Health Problem. http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/mtbi/report.htm.

- 20.Ruff R. Two decades of advances in understanding of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:5–18. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smits M, Hunink MG, Nederkoorn PJ, Dekker HM, Vos PE, Kool DR, Hofman PA, Twijnstra A, de Haan GG, Tanghe HL, Dippel DW. A history of loss of consciousness or post-traumatic amnesia in minor head injury: “conditio sine qua non” or one of the risk factors? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1359–1364. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.117143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Gandy S. Traumatic brain injury--football, warfare, and long-term effects. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1293–1296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1007051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson E. Officials Step Up Efforts to Detect, Prevent Brain Injury. American Forces Press Service; Mar 24, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarmiento K, Mitchko J, Klein C, Wong S. Evaluation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s concussion initiative for high school coaches: “Heads Up: Concussion in High School Sports”. J Sch Health. 2010;80:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zumstein MA, Moser M, Mottini M, Ott SR, Sadowski-Cron C, Radanov BP, Zimmermann H, Exadaktylos A. Long-term outcome in patients with mild traumatic brain injury: a prospective observational study. J Trauma. 2010 doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f2d670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Beaumont L, Theoret H, Mongeon D, Messier J, Leclerc S, Tremblay S, Ellemberg D, Lassonde M. Brain function decline in healthy retired athletes who sustained their last sports concussion in early adulthood. Brain. 2009;132:695–708. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putukian M. The acute symptoms of sport-related concussion: diagnosis and on-field management. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Traumatic brain injury--Colorado, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Utah, 1990-1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annegers JF, Grabow JD, Kurland LT, Laws ER., Jr The incidence, causes, and secular trends of head trauma in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1935-1974. Neurology. 1980;30:912–919. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.9.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Coan SP, Rocca WA. A population-based study of seizures after traumatic brain injuries. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:20–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801013380104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nemetz PN, Leibson C, Naessens JM, Beard M, Kokmen E, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Traumatic brain injury and time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:32–40. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown AW, Leibson CL, Malec JF, Perkins PK, Diehl NN, Larson DR. Long-term survival after traumatic brain injury: a population-based analysis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flaada JT, Leibson CL, Mandrekar JN, Diehl N, Perkins PK, Brown AW, Malec JF. Relative risk of mortality after traumatic brain injury: a population-based study of the role of age and injury severity. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:435–445. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown AW, Moessner AM, Mandrekar J, Diehl NN, Leibson CL, Malec JF. A survey of very-long-term outcomes after traumatic brain injury among members of a population-based incident cohort. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:167–176. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities . H-ICDA, Hospital Adaptation of ICDA. 2d ed Ann Arbor, MI: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melton LJ., 3rd The threat to medical-records research. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1466–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobsen SJ, Xia Z, Campion ME, Darby CH, Plevak MF, Seltman KD, Melton LJ., 3rd Potential effect of authorization bias on medical record research. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:330–338. doi: 10.4065/74.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malec JF, Brown AW, Leibson CL, Flaada JT, Mandrekar JN, Diehl NN, Perkins PK. The Mayo classification system for traumatic brain injury severity. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1417–1424. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leibson CL, Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Heit JA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Naessens JM, Bailey KR, Petterson TM, Ransom JE, Harris MR. Identifying in-hospital venous thromboembolism (VTE): a comparison of claims-based approaches with the Rochester Epidemiology Project VTE cohort. Med Care. 2008;46:127–132. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181589b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergstralh EJ, Offord KP, Chu CP, Beard CM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., III . Calculating Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates for Olmsted County, Minnesota: An Update. Mayo Clinic; Rochester: Apr, 1992. Technical Report No. 49. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berry G. The analysis of mortality by the subject-years method. Biometrics. 1983;39:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehmann EL, Romano JP. Springer Texts in Statistics. 3rd ed Springer; New York: 2005. Testing Statistical Hypotheses. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Holm L, Kraus J, Coronado VG, WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Methodological issues and research recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Rehabil Med. 2004:113–125. doi: 10.1080/16501960410023877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bazarian JJ, Veazie P, Mookerjee S, Lerner EB. Accuracy of mild traumatic brain injury case ascertainment using ICD-9 codes. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:31–38. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez SR, Mallonee S, Archer P, Gofton J. Evaluation of death certificate-based surveillance for traumatic brain injury--Oklahoma 2002. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:282–289. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powell JM, Ferraro JV, Dikmen SS, Temkin NR, Bell KR. Accuracy of mild traumatic brain injury diagnosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1550–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deb S. ICD-10 codes detect only a proportion of all head injury admissions. Brain Inj. 1999;13:369–373. doi: 10.1080/026990599121557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375–378. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burt CW, Hing E. Making patient-level estimates from medical encounter records using a multiplicity estimator. Stat Med. 2007;26:1762–1774. doi: 10.1002/sim.2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fife D, Faich G, Hollinshead W, Boynton W. Incidence and outcome of hospital-treated head injury in Rhode Island. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:773–778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.7.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacKenzie EJ, Edelstein SL, Flynn JP. Hospitalized head-injured patients in Maryland: incidence and severity of injuries. Md Med J. 1989;38:725–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schootman M, Fuortes LJ. Ambulatory care for traumatic brain injuries in the US, 1995-1997. Brain Inj. 2000;14:373–381. doi: 10.1080/026990500120664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kibby MY, Long CJ. Minor head injury: attempts at clarifying the confusion. Brain Inj. 1996;10:159–186. doi: 10.1080/026990596124494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nemetz PN, Leibson C, Naessens JM, Beard M, Tangalos E, Kurland LT. Determinants of the autopsy decision: a statistical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:175–183. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/108.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooper DB, Kennedy JE, Cullen MA, Critchfield E, Amador RR, Bowles AO. Association between combat stress and post-concussive symptom reporting in OEF/OIF service members with mild traumatic brain injuries. Brain Inj. 2011;25:1–7. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.531692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwarz A. Former Bengal Henry Found to Have Had Brain Damage. The New York Times; New York: Jun 29, 2010. p. B10. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.