Abstract

Purpose

Type-2 diabetes is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and elevated C-reactive protein levels (CRP). Aerobic exercise training has been shown to improve CRP, however there are limited data evaluating the effect of other exercise training modalities (aerobic, resistance or combination training) in individuals with type-2 diabetes.

Methods

Participants (n=204) were randomized to an aerobic exercise (aerobic), resistance exercise (resistance) or a combination of both (combination) for nine months. CRP was evaluated at baseline and at follow-up.

Results

Baseline CRP was correlated with fat mass, waist circumference, BMI, and VO2 peak (p<0.05). CRP was not reduced following aerobic (0.16 mg·L -1, 95% CI: −1.0, 1.3), resistance (−0.03 mg·L -1, 95% CI: −1.1, 1.0) or combination (−0.49 mg·L -1, 95% CI: −1.5 to 0.6) training compared to control (0.35 mg·L -1, 95% CI: −1.0, 1.7). Change in fasting glucose (r=0.20, p=0.009), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) (r=0.21 p=0.005), and fat mass (r=0.19, p=0.016) were associated with reductions in CRP, but not change in fitness or weight (p > 0.05). There were significant trends observed for CRP among tertiles of change in HbA1C (p=0.009) and body fat (p=0.040).

Conclusion

Aerobic, resistance or a combination of both did not reduce CRP levels in individuals with type-2 diabetes. However, exercise related improvements in HbA1C, fasting glucose, and fat mass were associated with reductions in CRP.

Keywords: Inflammation, Aerobic Training, Resistance Training, Hemoglobin A1C, Adiposity, Fitness

Introduction

Chronic systemic inflammation has been implicated in the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (16, 18), and tends to be elevated in individuals with type-2 diabetes (18). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) is a marker of systemic inflammation that is released by hepatocytes in response to cytokines (i.e.: interleukins, tumor necrosis factor alpha) (21). Epidemiological studies have found that elevated CRP is an independent predictor for cardiovascular events (17) and CVD mortality (19) in individuals with type-2 diabetes. Therefore, intervention strategies that reduce CRP may have important clinical implications.

Aerobic fitness is inversely associated with CRP levels (4, 15), and exercise training has been shown to reduce CRP in individuals with type-2 diabetes (3, 10). Evidence from large randomized studies in non-diabetic populations suggests that training related improvements are due to weight/adiposity reduction following exercise training (7, 20). However, smaller training studies in individuals with type-2 diabetes indicate that changes in fitness (3), waist circumference (3) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (10) are associated with improvements in CRP (3), though these results have not been replicated in a large randomized trial.

Although exercise training may have some efficacy through direct or indirect means in reducing CRP, there are limited data on the effect of different training modalities (3, 14). The American College of Sports Medicine and American Diabetes Associations joint position stand on exercise and type-2 diabetes (2) recommends a combination of aerobic and resistance training, as opposed to aerobic alone to maximize the improvement of glycemic control. Similarly, there are data to suggest that combination training may result in a greater reduction in CRP than resistance or aerobic training alone. Balducci et al. (3) found a significant 28% and 54% reduction in CRP after one year of aerobic and combination training (aerobic plus resistance exercise), respectively with a significant reduction in body weight in the combination training group and no changes in body fat in any of the exercise groups. However, the independent effects of aerobic, resistance, or a combination of both training modalities on CRP levels have not been examined to our knowledge. In addition, the effect of exercise training modalities on CRP in individuals with type-2 diabetes has not been replicated in a larger randomized trial. The purpose of our present study was to evaluate the effect of aerobic, resistance training, or combination of both on CRP levels in individuals with type-2 diabetes from the Health Benefits of Aerobic and Resistance Training in Individuals with Type-2 Diabetes (HART-D) study. As a secondary aim, we evaluated the effect of changes in hemoglobin-A1C (HbA1C), fasting glucose, fitness, and fat mass with exercise training on changes on CRP levels.

Methods

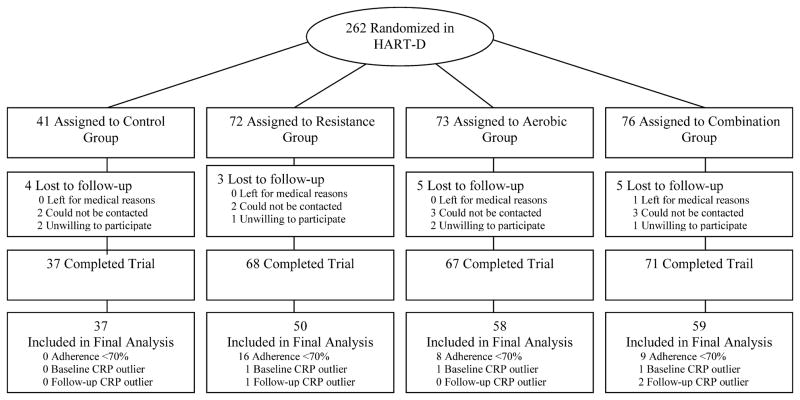

The primary outcomes report for HART-D have been published (5). Briefly, HART-D was a 9 month exercise study comparing the effects of aerobic, resistance, or a combination of both training modalities on hemoglobin-A1C (HbA1C) in participants with type-2 diabetes. The primary outcome for the present ancillary study is the examination of changes in CRP from baseline and follow-up, which was not reported in the main HART-D outcomes paper (5) study due to space limitations. The consort diagram is shown in Figure 1. In the parent HART-D study, there were a total of 262 sedentary 30 to 75-year old adults with type-2 diabetes presenting with an HbA1C of 6.5% to 11.0%, from which 243 participants had CRP data at baseline to follow-up. Of this sample, 210 participants were adherent (≥70%) with the exercise training program and 204 were included in the final analysis (6 outliers were removed). Notable exclusion criteria included a body mass index (BMI) > 48 kg/m2, blood pressure 160/100 mmHg or higher, fasting triglycerides 500 mg/dL or higher, use of an insulin pump, urine protein greater than 100 mg/dL, history of stroke, advanced neuropathy, or retinopathy, or any serious medical condition that prevented participant adherence to the study protocol or was a contraindication for exercise training. The institutional review board at Pennington Biomedical Research Center approved the protocol annually and all participants provided written informed consent before initiating the any of the study protocols.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram- Shown is the consort diagram for the present study

Study Design

Full details of the exercise training program used in HART-D has been reported in the main outcomes paper (5). Participants were randomized to one of four groups: a non-exercise control group, aerobic training only (aerobic), resistance training only (resistance) or a combination of resistance and aerobic training (combination). The non-exercise control group was offered weekly stretching and relaxation classes and was asked to maintain their current activity during the 9-month study period. All exercise sessions were supervised by study staff in our exercise training laboratory.

Exercise Training

The exercise intensity for aerobic exercise training was 50% to 80% of maximal oxygen consumption. Discussion of how the dose of exercise was chosen for each group has been reported previously in the main outcomes paper (5). The selected dose of exercise for the aerobic group was 12 kcal/kg/week and 10 kcal/kg/week for the combination exercise group. American College of Sports Medicine equations were used to estimate caloric expenditure rate and time required for each session (1). Total adherence was calculated as the estimated kilocalories expended divided by the total amount of kilocalories required per protocol. Exercise time during aerobic training was calculated as the average weekly minutes accumulated over the course of the exercise intervention. An extensive report on intervention data monitored during the intervention has been reported in the main outcomes paper (5).

Participants in the resistance training group exercised 3 days per week with each session consisting of 2 sets of 4 upper body exercises (bench press, seated row, shoulder press and lat pull down), 3 sets of 3 leg exercises (leg press, extension, and flexion) and 2 sets of each abdominal crunches and back extensions. Each set of resistance exercise consisted of 10 to 12 repetitions. Individuals in the combination exercise group had two resistance sessions per week with each sessions consisting of 1 set of each of the 9 exercises. Weight was progressively increased once the participant was able to complete 12 repetitions for each set of exercises on 2 consecutive exercise sessions. Participants were weighed weekly to calculate the energy expenditure target for each participant.

The control group was unblinded after participants (17.1%) had an increase in HbA1C level of 1.0% or higher. With the data safety monitoring board recommendation, we discontinued randomization into the control group (5). Thus, fewer participants who completed the study in the control group compared to the other randomization groups.

Exercise Testing

Exercise testing was performed on a treadmill (Trackmaster 425, Carefusion, Newton Kansas) with respiratory gasses sampled using a True Max 2400 Metabolic Measurement Cart (Parvomedics, Salt Lake City Utah). Participants self-selected a walking pace and the grade increased by 2% every 2 minutes until exhaustion. We performed all muscular strength assessments using a Biodex System 3 dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, New York). Total work was determined as the total work accomplished for 30 repetitions of maximal effort. Fat mass and lean mass was determined using a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans were performed using the QDR 4500A whole body scanner (Hologic Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts). Fitness and muscular strength testing were performed at baseline and follow-up.

There were separate intervention and assessment teams and all assessment staff was blinded to participant randomization. The clinical testing and exercise training laboratories were in separate buildings, and participants were reminded frequently not to disclose their group assignment to assessment staff.

Blood Samples

CRP was measured using a solid phase chemiluminescent immunometric assay on Immulite 2000 analyzer (Siemens, Deerfield, Illinois) at baseline and follow-up following an overnight fast. Samples were stored at −80 C°, batched and analyzed at the conclusion of the HART-D trial. The assay had a sensitivity of 0.2 mg/dL. The coefficient of variation (CV) for CRP was tested at 3 levels. The CV at level 1 (mean: 1.4 mg/dL SD: 0.08), level 2 (mean: 7.4 mg/dL SD: 0.58) and level 3 (mean: 73.3 mg/dL, SD: 5.6) were 5.2%, 7.7% and 7.7% respectively. Insulin was measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay with a sensitivity: 2uIU/ml. on Siemens 2000 (Siemens, Deerfield, Illinois). The CV of the insulin assay at level 1 (mean: 10.4 uIu/ml, SD:0.1) was 5.6% and at level 2 (mean: 46.5 uIU/ml, SD: 2.9 was 6.3%. Glucose was measured using a DXC 600 Pro (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, California). The glucose assay had a sensitivity of 10 mg/dl. The CV at level 1 (mean: 80.0 mg/dL, SD: 2) was 3.1% and level 2 (mean: 284 mg/dL, SD: 8) was 2.8%. HbA1C was evaluated from venopuncture and samples were run on a DXC 600 Pro (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, California). The HbA1c assay had a sensitivity of 2 mg/dL. The CV at level 1 was 2.3% (mean: 5.6 %, SD:0.1) and CV at level 2 was 3.4% (mean: 9.6%, SD:0.3). Results from blood analyses were determined from a single measurement (not in duplicate) at baseline and follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

All data was analyzed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). The final analysis of the present study was performed in adherent participants (n=204) (70% adherent to exercise intervention) with outliers removed. We adopted a conservative analysis plan and removed outliers with CRP values greater than 3 SD above the mean for baseline or post-training CRP. Results were similar when the same analysis was performed with outliers included. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare baseline characteristics between groups of continuous variables, and a chi-squared test (χ2) was used to compare baseline characteristics between categorical variables. Correlations between baseline CRP and baseline fitness, body composition measures and blood analyses were analyzed with spearman correlations. Additionally, the correlation of the change in CRP following exercise training and change in fitness, body composition measures and blood analyses were evaluated in exercisers only (n=169). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine the effect of the intervention on change in CRP levels, fitness, body composition, and strength variables with baseline value entered as a covariate. Results are presented as adjusted least square means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We evaluated the change in CRP among tertiles of changes in HbA1C, fasting glucose, fitness and body fat in exercisers. An ANCOVA was used to test for significant differences with baseline CRP entered into the model as a covariate. In addition, we tested the trend across tertiles with multiple linear regression with adjustment for baseline value. A p value of <0.05 was used as the criteria for statistical significance for all analyzes.

Results

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. The study sample had a mean (SD) age of 57.3 (8.1) yrs; a mean weight of 97.5 (19.0) kg; a mean BMI of 34.5 (5.9) kg/m2; was 61% female; and was ethnically diverse as approximately 44% of our study sample was non-Caucasian. The mean baseline CRP in our sample was 4.7 (5.1) mg·L−1. CRP was significantly higher in women than men (5.7 vs. 3.1 mg·L−1, p= 0.003), African Americans compared to Caucasians (6.6 vs. 3.6 mg·L−1, p=0.001), participants on insulin medication compared to individuals not taking insulin (6.6 vs. 4.4 mg·L−1 p=0.020), and individuals not on cholesterol medications compared to individuals taking cholesterol medications (6.2 vs. 4.0 mg·L−1, p=0.032). However, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between experimental groups (all P> 0.05). Total adherence to aerobic training was aerobic and combination groups was 90.9% (9.1) and 91.9% (9) respectively in the present ancillary study. Similarly, adherence to resistance training in the resistance and the combination group was 92.4 (10.6) and 88.4 (10.5) respectively. The average exercise time during aerobic training in the aerobic and the combination groups were 121.6 (23.1) and 106.4 (21.4) minutes respectively. The average amount of sessions per week were 3.1 (0.16) and 3.0 (0.13) in the aerobic and combination groups respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics- Shown are the baseline characteristics of participants in the present study. Data are presented as mean (SD).

| Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomization Groups

| ||||

| Control (n= 37) | Aerobic (n=50) | Resistance (n=58) | Combination (n=59) | |

| Age (yr) | 58.5 (8.6) | 55.8 (7.9) | 58.7 (8) | 56.7 (7.8) |

| Female (%, n) | 70.3 (26) | 60.0 (30) | 55.2 (32) | 61.0 (36) |

| Ethnicity (%, n) | ||||

| Caucasian, | 51.4 (19) | 60.0 (30) | 60.3 (35) | 50.9 (30) |

| African American | 43.2 (16) | 40.0 (20) | 37.9 (22) | 40.0 (23) |

| Hispanic/Other | 5.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 1.7 (1) | 10.2(6) |

| Weight (kg) | 96 (20.6) | 96.5 (18.1) | 97.4 (16.8) | 99.1 (21.1) |

| Absolute VO2 (L/min) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.5) |

| Relative VO2 (mL·kg−1·min −1) | 18.3 (3.7) | 19.6 (4) | 19.6 (4.4) | 19 (3.5) |

| Muscular work (N m) | ||||

| Flexion | 962.2 (402.4) | 1041.2 (532.0) | 988.8 (569.6) | 984.8 (469.1) |

| Extension | 1977.1 (898.6) | 2338.1 (882.8) | 2253.1 (814.4) | 2267.4 (866.9) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126.6 (14.5) | 124.4 (11.7) | 125.4 (12.7) | 130.4 (13.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76.4 (8.2) | 75 (9.2) | 74.9 (8.3) | 74.7 (8.5) |

| HbA1C (%) | 7.6 (0.9) | 7.3 (0.8) | 7.6 (0.9) | 7.5 (0.9) |

| Fat mass (kg) | 35.1 (9.4) | 36.4 (10.1) | 37.8 (11.3) | 36.7 (10.6) |

| Lean mass (kg) | 57.4 (11.3) | 58.3 (10.5) | 57.9 (12.2) | 57.5 (11.4) |

| Body fat (%) | 38.5 (6.7) | 36.8 (7.5) | 37.1 (7.7) | 38.1 (6.8) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 109.4 (14.5) | 110.3 (13.8) | 111.9 (12.6) | 113 (14.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.7 (6.4) | 33.9 (5.7) | 34.1 (5.4) | 35 (6.2) |

| CRP (mg·L −1) | 5.2 (6.2) | 4.3 (4.9) | 4.1 (4.5) | 5.4 (5.1) |

| Diabetes duration | 6.9 (4.9) | 7.6 (5.9) | 7.7 (5.7) | 6.8 (5.6) |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 151.4 (29.7) | 140.4 (27.6) | 152.2 (39.4) | 144.4 (28.5) |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 18.1 (15.4) | 17 (15.8) | 20.9 (15.3) | 16.6 (8.7) |

| Diabetes medication (%, n) | 97.3 (36) | 94.0 (47) | 100.0 (58) | 98.3 (58) |

| Biguanide | 56.8 (21) | 70.0 (35) | 60.3(35) | 72.9 (43) |

| Sulfonylureas | 27.0 (10) | 28.0 (14) | 27.6 (16) | 17.0 (10) |

| Thiazolidnediones | 21.6 (8) | 26.0 (13) | 17.2 (10) | 17.0 (10) |

| Combo Class | 21.6 (8) | 12.0 (6) | 19.0 (11) | 17.0 (10) |

| Incretin Class | 8.1 (3) | 12.0 (6) | 13.8 (8) | 10.2 (6) |

| Insulin | 18.9 (7) | 14.0 (7) | 15.2 (9) | 18.6 (11) |

| Cholesterol medication (%, n) | 56.8 (21) | 70.0 (35) | 72.4 (42) | 67.8 (40) |

| Statin class | 54.1 (20) | 66.0 (33) | 69.0 (40) | 66.1 (39) |

Baseline CRP was correlated with body fat (r=0.38, p<0.001), waist circumference (r= 0.27, p<0.001), weight (r= 0.28, p<0.001), BMI (r=0.43, p<0.001), diastolic blood pressure (r=0.19 p=0.006) and relative VO2 peak (r= −0.27, p <0.001), but not with absolute VO2 peak, HbA1C, systolic blood pressure, or muscular work (p> 0.05).

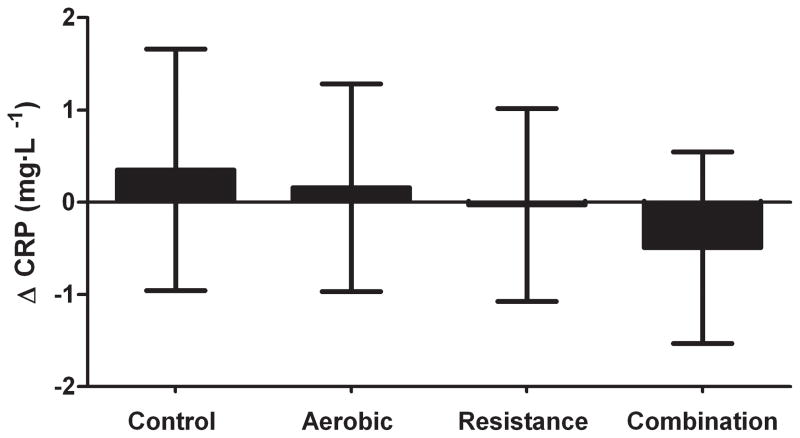

Change in CRP with exercise training

The results of the ANCOVA evaluating the change in CRP with exercise training are shown in Figure 2. There was no significant change in CRP in the aerobic (0.15 mg·L−1; 95% CI: −0.97, 1.28 ), resistance (−0.03 mg·L−1; 95% CI: −1.08, 1.02), or combination (−0.49 mg·L−1; 95% CI: −1.52, 0.55) groups compared with control participants (0.35 mg·L−1, 95% CI: −0.96, 1.65).

Figure 2.

The effect of exercise modality (aerobic, resistance or combination of both) on CRP levels. Shown are the results of an ANCOVA adjusted for baseline value. Results are presented in adjusted least square means with 95% confidence intervals.

Change in Fitness, body composition and glucose metabolism following exercise training

The changes in fitness, body composition and anthropometrics for this cohort are shown in Table 2, and are similar to our result of our main outcomes paper (5). There was a significant reduction in percentage body fat in the resistance and combination group, but not for the aerobic group compared to control. Fat mass was significantly decreased in the aerobic, resistance and combination groups compared to control. HbA1C levels were significantly reduced in only the combination group compared to control. Fasting insulin and glucose values were not significantly altered by exercise training. Body weight was significantly reduced in only the combination group. Waist circumference was improved in all three exercise groups compared to control. Muscular work during flexion was significantly improved in the resistance group compared to the control, aerobic and combination groups. Muscular work extension was improved in the resistance and combination groups compared to the control. Absolute and relative peak VO2 was only improved in the combination group, but approached significance in the aerobic group (p=0.096). Peak mean respiratory exchange ratio at baseline and follow-up were 1.14 (0.087) and 1.12 (0.075) respectively. Maximum heart rate during exercise testing was 156.1 (18.8) and 154.7 (21.0) beats per minute at baseline and follow-up respectively.

Table 2.

Shown are the effect of exercise training on body composition, glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity variables. ANCOVA is corrected for baseline value.

| Variable | Control | Aerobic | Resistance | Combination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body fat (%) | 0.21 (−0.4 to 0.8) | −0.42 (−0.9 to 0.1) | −1.09 (−1.5 to −0.6) * | −1.05 (−1.5 to −0.6) * |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.24 (−0.1 to 0.5) | −0.15 (−0.4 to 0.1) | −0.16 (−0.4 to 0.1) | −0.34 (−0.6 to −0.1) * |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 7.54 (−5.1 to 20.1) | 2.96 (−7.6 to 13.5) | 4.76 (−5 to 14.6) | 0.46 (−9.2 to 10.2) |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | −3.61 (−6.9 to −0.4) | −1.53 (−4.3 to 1.3) | −1.89 (−4.5 to 0.7) | −2.05 (−4.7 to 0.6) |

| Relative fitness (mL·kg-1·min -1) | −0.33 (−1.1 to 0.5) | 0.57 (−0.1 to 1.2) | 0.09 (−0.5 to 0.7) | 1.17 (0.5 to 1.8) * |

| Absolute fitness (L/min) | −0.02 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 0.02 (0 to 0.1) | 0.01 (0 to 0.1) | 0.1 (0 to 0.2) * |

| Weight (kg) | 0.36 (−0.8 to 1.5) | −1.05 (−2 to −0.1) | −0.03 (−0.9 to 0.8) | −1.35 (−2.2 to −0.5) * |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.62 (−0.8 to 2) | −1.67 (−2.8 to −0.5) * | −1.76 (−2.9 to −0.7) * | −2.49 (−3.6 to −1.4) * |

| Fat mass (kg) | 0.23 (−0.62 to 1.07) | −0.94 (−1.67 to −0.22) * | −1.15 (−1.8 to −0.5) * | −1.6 (−2.27 to −0.93) * |

| Lean mass (kg) | 0.13 (−0.54 to 0.8) | −0.44 (−1 to 0.13) | 0.92 (0.41 to 1.44) | 0.04 (−0.49 to 0.56) |

| Muscular work flexion (N m) | 15.75 (−142.8 to 174.3) | 63.15 (−67.6 to 193.9) | 351.96 (229.5 to 474.4) *δ‡ | 139.53 (16 to 263) |

| Muscular work extension (N m) | 80 (−68.5 to 228.5) | 117.3 (−5.9 to 240.5) | 551.95 (436.9 to 667) *δ‡ | 282.83 (168.8 to 396.8) * |

Significantly different from the control group.

Significantly different from aerobic group.

Significantly different from combination group.

Change in glucose metabolism, body composition and fitness on change in CRP

Change in CRP following exercise training in exercisers was correlated with change in HbA1C (r=0.21 p=0.005), fasting glucose (r=0.20, p= 0.009), fat mass (r=0.19, p=0.016) and body fat percentage (r=0.14, p= 0.07). There were no significant correlations observed for change in peak VO2, weight, BMI, waist circumference, lean mass, or muscular work with change in CRP (all Ps > 0.05), and approached significance for change in insulin (r=0.17, p= 0.132).

Changes in CRP among tertiles of changes in glucose metabolism, fitness and body composition variables in exercisers are shown in Table 3. There was a significant reduction in CRP among participants who had the greatest reduction in HbA1C (Tertile 1: −1.25%, 95 % CI: −2.4, −0.1) compared to participants who had the greatest increase in HbA1C (Tertile 3: 1.02 %, 95% CI: −0.2, 2.2). Additionally, there was a significant trend observed for tertile of change in HbA1C and change in CRP (p-trend=0.009). For body fat, the overall ANCOVA was not significant, however there was a significant trend observed for change in CRP across tertiles of change in fat mass (p= 0.040). There were no significant relationships found for tertiles of glucose, fitness, weight, or insulin for either ANCOVA or trend analyses (all ps >0.05).

Table 3.

Shown are the changes in tertiles of glucose metabolism, fitness and body composition with change in CRP. Multiple linear regression was performed for trend analysis and an ANCOVA with adjustment for baseline value.

| Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 | p-trend | Overall ANCOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ HbA1C (%) | −1.25 | −0.02 | 1.02 * | 0.009 | 0.036 |

| Δ Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | −0.53 | −0.52 | 0.77 | 0.132 | 0.222 |

| Δ Peak VO2 (mL·kg-1·min -1) | 0.17 | −0.05 | −0.95 | 0.175 | 0.358 |

| Δ Weight (kg) | −0.71 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.367 | 0.653 |

| Δ Insulin (pmol/L) | −0.96 | −0.01 | 0.69 | 0.070 | 0.193 |

| Δ Fat mass (Kg) | −0.92 | −0.53 | 0.77 | 0.040 | 0.100 |

indicates a significant difference compared to tertile 1. A p value of 0.05 was used as the criteria for statistical significance.

Discussion

The primary finding of the present study is that exercise training modality (aerobic, resistance or a combination of both) had no significant effect on CRP levels in individuals with type-2 diabetes. However, exercise training related improvements in chronic glucose control as denoted by HbA1C and fat mass were associated with a larger reduction in CRP. Our results suggest that improving glycemic control and reducing fat mass in individuals with type-2 diabetes may be key factors in the reduction of CRP levels, which is an independent predictor for CVD (17).

This is the first large randomized study in individuals with type-2 diabetes to our knowledge evaluating the effect of exercise modality on CRP levels with distinct aerobic only, resistance only and combination (aerobic and resistance) exercise group. Our results are in contrast to a similar smaller study by Balducci et al. (3) who found significant reductions in CRP with aerobic (−28%), combined aerobic and resistance training, (−54%), and exercise counseling (−12%) in individuals with type-2 diabetes without significant reductions in fat mass, BMI or weight. Although there were larger reductions in HbA1C than the present study, the authors did not find a relationship in their sample between change in HbA1C levels and CRP. In contrast, they found that change in VO2 max, exercise volume, exercise type and change in waist circumference were associated with change in CRP. This may be attributed to differences between studies such as the resistance programs used in the combination group (Balducci et al: 20 minutes of resistance exercise vs. HART-D: one set of 9 resistance exercises), study length (Balducci et al.: one year, HART-D: 9 months) and potentially racial/ethnic differences (Balducci et al.: Italian population, HART-D: American (40% African American). It is also plausible that differences between studies may be related to aerobic exercise intensity. Balducci et al.’s study trained at a higher range of VO2 max (70–80%), whereas the mean percent of VO2 peak during the exercise intervention in the aerobic group was 64.8% and the combination group was 64.1% in HART-D.

It is unlikely that the lack of significant results in the present study were due to methodological issues as our research team has extensive experience in implementation of large exercise training interventions (5–7), and there was excellent compliance and retention in the HARD-D study (5). Similarly, it is unlikely that our results were influenced by changes in diet or physical activity outside the intervention. Daily step counter data worn outside the training program showed no significant changes in physical activity and analysis of food frequency questionnaires revealed no significant alterations in dietary habits (5). In addition, previous studies have shown no significant change in CRP following aerobic training in individuals with type-2 diabetes (9, 22).

The results of the present study are in agreement with evidence from other large randomized trials which found no change in CRP levels following exercise training (7, 20). However, both the Dose Response to Exercise in Women trial (n=462) and the Inflammation and Exercise Study (INFLAME) (n=162) found that the exercise training related reductions in weight were associated with improvements in CRP (7, 20). In the present study, BMI and weight were associated with CRP levels at baseline, but we observed no significant relationship between changes in weight, BMI, waist circumference or fitness measures following exercise training and CRP. Nevertheless, we did see a correlation between change in CRP and change in fat mass, which is in agreement with the results of INFLAME (7). To our knowledge, HART-D is the first study to find that exercise training related improvements in HbA1C are associated with improvements in CRP in individuals with type-2 diabetes. Our observations are supported by epidemiological studies which found that CRP is elevated in populations with type-2 diabetes (8, 12, 13). King et al. (12) found that in individuals with type-2 diabetes (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III) a 1.0% increase in HbA1C was associated with a 20% increase in the likelihood of having elevated CRP. Hyperglycemia is believed to contribute to elevated inflammation and atherogenesis via increasing levels of oxidative stress, inflammatory markers (tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6), and vascular adhesion molecules (11).

The strengths of the present study is that HART-D is a randomized controlled trial with a large study sample (n=204) in which exercise dose was strictly monitored and controlled. In addition, we used federal guidelines to design our exercise prescriptions, and all randomization groups exercised for a similar amount of time. Furthermore, we had an aerobic only, resistance only and a combination training group, so we are able to evaluate the independent effects of aerobic and resistance training, which is in contrast to previous studies on CRP and exercise modality (3, 14). However, it is possible that different results may be achieved with different modes of training (e.g. interval) or different amounts of aerobic and resistance exercise within combination training programs. The largest reduction in CRP following exercise training occurred in the combination group (albeit non-significant) along with a significant reductions in HbA1C and fat mass, which was not achieved in the resistance or aerobic groups. In HART-D, the combination group participated in one set of resistance exercise per session twice per week. Since muscle mass is involved in glucose uptake, perhaps more resistance training within combination training programs is necessary to reduce CRP (2). Lastly, although we collected information about participant medications, we did not categorize medications as anti-inflammatory in HART-D. Therefore our analyses are not adjusted specifically for individuals taking anti-inflammatory medication.

In conclusion, the results of the present study found that aerobic, resistance or a combination of both training modalities did not significantly reduce CRP levels in individuals with type-2 diabetes. However, we found that reductions in CRP are influenced by reduction in HbA1C, fasting glucose, and fat mass. Although our data do not support that combination training program used in the present study can lower CRP levels, the exercise related improvements in HbA1C and fat mass would suggest it has greater promise than aerobic or resistance training alone. Future research should evaluate the effect of different combination training programs on CRP with the goal of improving chronic glucose control and maximizing fat loss in individuals with type-2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The HART-D study was funded by The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (R01 DK068298, Clinical Trials.gov #: NCT00458133). We thank all HART-D participants and the Pennington Biomedical Research Center staff members Gina Billiot, Sheletta Donatto, RD, and Ronald Monce, PA-C, for their hard work and commitment. In addition we thank the HART-D data and safety monitoring board and Scientific Advisory Board, and Pennington Biomedical Research Center faculty members William Cefalu, MD, Steve Smith, MD (now at Burnham Institute in Orlando, Florida), and Jennifer Rood, PhD, for their scientific guidance both in planning and conducting the study. Part of Ms Donatto and Mr Monce’s salaries were supported through the HART-D grant, and Dr. Rood’s laboratory was reimbursed for clinical laboratory measures. Members of the data and safety monitoring board were provided modest honorariums for their time. Drs. Cefalu and Dr. Smith and the Scientific Advisory Board received no compensation for their contributions. Additionally, we would like to thank the NIH T-32 postdoctoral fellowship, which supports to salary and training of Dr. Damon Swift. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams& Williams; 2010. pp. 139–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Sports Medicine. Exercise and Type 2 Diabetes: American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: Joint Position Statement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(12):2282–303. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181eeb61c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, Fernando F, Cavallo S, Cardelli P, Fallucca S, Alessi E, Letizia C, Jimenez A, Fallucca F, Pugliese G. Anti-inflammatory effect of exercise training in subjects with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome is dependent on exercise modalities and independent of weight loss. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20(8):608–17. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Church TS, Barlow CE, Earnest CP, Kampert JB, Priest EL, Blair SN. Associations Between Cardiorespiratory Fitness and C-Reactive Protein in Men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(11):1869–76. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000036611.77940.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S, Johannsen N, Johnson W, Kramer K, Mikus CR, Myers V, Nauta M, Rodarte RQ, Sparks L, Thompson A, Earnest CP. Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Training on Hemoglobin A1c Levels in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(20):2253–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN. Effects of Different Doses of Physical Activity on Cardiorespiratory Fitness Among Sedentary, Overweight or Obese Postmenopausal Women With Elevated Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2007;297(19):2081–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.19.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Church TS, Earnest CP, Thompson AM, Priest EL, Rodarte RQ, Saunders T, Ross R, Blair SN. Exercise without Weight Loss Does Not Reduce C-Reactive Protein: The INFLAME Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(4):708–16. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c03a43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Rekeneire N, Peila R, Ding J, Colbert LH, Visser M, Shorr RI, Kritchevsky SB, Kuller LH, Strotmeyer ES, Schwartz AV, Vellas B, Harris TB. Diabetes, Hyperglycemia, and Inflammation in Older Individuals. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1902–8. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dekker MJ, Lee S, Hudson R, Kilpatrick K, Graham TE, Ross R, Robinson LE. An exercise intervention without weight loss decreases circulating interleukin-6 in lean and obese men with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2007;56(3):332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannopoulou I, Fernhall B, Carhart R, Weinstock RS, Baynard T, Figueroa A, Kanaley JA. Effects of diet and/or exercise on the adipocytokine and inflammatory cytokine levels of postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2005;54(7):866–75. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg RB. Cytokine and Cytokine-Like Inflammation Markers, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Imbalanced Coagulation in Development of Diabetes and Its Complications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3171–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King DE, Mainous AG, Buchanan TA, Pearson WS. C-Reactive Protein and Glycemic Control in Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1535–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levinger I, Goodman C, Peake J, Garnham A, Hare DL, Jerums G, Selig S. Inflammation, hepatic enzymes and resistance training in individuals with metabolic risk factors. Diabet Med. 2009;26(3):220–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martins R, Neves A, Coelho-Silva M, Veríssimo M, Teixeira A. The effect of aerobic versus strength-based training on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in older adults. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;110(1):161–9. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGavock JM, Mandic S, Vonder Muhll I, Lewanczuk RZ, Quinney HA, Taylor DA, Welsh RC, Haykowsky M. Low Cardiorespiratory Fitness Is Associated With Elevated C-Reactive Protein Levels in Women With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):320–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nystrom T. C-reactive protein: A marker or a player? Clin Sci. 2007;113(1–2):79–81. doi: 10.1042/CS20070121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulze MB, Rimm EB, Li T, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. C-Reactive Protein and Incident Cardiovascular Events Among Men With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(4):889–94. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjoholm A, Nystrom T. Inflammation and the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes-Metab Res Rev. 2006;22(1):4–10. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soinio M, Marniemi J, Laakso M, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T. High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Coronary Heart Disease Mortality in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):329–33. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart LK, Earnest CP, Blair SN, Church TS. Effects of Different Doses of Physical Activity on C-Reactive Protein among Women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(4):701–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c03a2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson AM, Ryan MC, Boyle AJ. The novel role of C-reactive protein in cardiovascular disease: Risk marker or pathogen. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106(3):291–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoppini G, Targher G, Zamboni C, Venturi C, Cacciatori V, Moghetti P, Muggeo M. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise training on plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;16(8):543–9. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]