Abstract

Background

Nursing homes provide long-term housing, support and nursing care to frail elders who are no longer able to function independently. Although studies conducted in the United States have demonstrated an association between for-profit ownership and inferior quality, relatively few Canadian studies have made performance comparisons with reference to type of ownership. Complaints are one proxy measure of performance in the nursing home setting. Our study goal was to determine whether there is an association between facility ownership and the frequency of nursing home complaints.

Methods

We analyzed publicly available data on complaints, regulatory measures, facility ownership and size for 604 facilities in Ontario over 1 year (2007/08) and 62 facilities in British Columbia (Fraser Health region) over 4 years (2004–2008). All analyses were carried out at the facility level. Negative binomial regression analysis was used to assess the association between type of facility ownership and frequency of complaints.

Results

The mean (standard deviation) number of verified/substantiated complaints per 100 beds per year in Ontario and Fraser Health was 0.45 (1.10) and 0.78 (1.63) respectively. Most complaints related to resident care. Complaints were more frequent in facilities with more citations, i.e., violations of the legislation or regulations governing a home, (Ontario) and inspection violations (Fraser Health). Compared with Ontario’s for-profit chain facilities, adjusted incident rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals of verified complaints were 0.56 (0.27–1.16), 0.58 (0.34–1.00), 0.43 (0.21– 0.88), and 0.50 (0.30– 0.84) for for-profit single-site, non-profit, charitable, and public facilities respectively. In Fraser Health, the adjusted incident rate ratio of substantiated complaints in non-profit facilities compared with for-profit facilities was 0.18 (0.07–0.45).

Interpretation

Compared with for-profit chain facilities, non-profit, charitable and public facilities had significantly lower rates of complaints in Ontario. Likewise, in British Columbia’s Fraser Health region, non-profit owned facilities had significantly lower rates of complaints compared with for-profit owned facilities.

Nursing homes (referred to as “residential care facilities” in British Columbia and as “long-term care facilities” in Ontario) are licensed and regulated institutions that provide long-term housing, 24-hour support and nursing care to mainly frail elders who are no longer able to function independently. Many nursing home residents have dementia, and a majority are women on low incomes.1 Moreover, nursing home residents have increasingly greater levels of disability and higher care needs over time,2 and facilities are challenged to provide high-quality care within the current constraints of their funding. Decision-makers,3 the public4 and academics5,6 have all expressed concerns about the quality of care in nursing homes. Indeed, the provincial Ombudsmen in Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec have recently released reports on this sector in response to such concerns.7-9

Hirschman describes two options for consumers of health care to exercise some control over perceived poor care.10 The first is “exit”—in this case, the ability to move to another facility. However, the ability to exit is typically limited for nursing home residents, and the actual transfer rate was found to be as low as 3.3% in one study of 4 US states.11 A resident’s second option is “voice” —the ability to lodge a complaint with the expectation that a perceived shortcoming will be remedied.12 However, this is also challenging for nursing home residents. Many are cognitively impaired or may fear retaliation from facility staff. In addition, the procedure for lodging a complaint may not be well known or may be quite onerous. On the other hand, the option to lodge a formal complaint with regulators is available in most jurisdictions and can be made at any time by the resident or any other individual who wishes to do so. Therefore, some researchers have argued that complaints potentially represent an additional indicator of quality.13

Stevenson examined national data on complaints in the United States and found that the frequency of complaints varied in a manner consistent with some but not all other quality measures. The author demonstrated that a higher frequency of complaints in one yearly quarter predicted a greater likelihood of deficiencies found in subsequent inspections and that complaints were negatively associated with levels of nurse and nurse aid staffing.12 This study also found a higher rate of complaints in for-profit facilities as compared with non-profit facilities.12

In Canada and many other Western countries, most nursing homes are funded publicly although the ownership of these facilities may be private (for-profit), non-profit (religious or community non-profit society), or public (government or government-established body). Prior research, largely from the United States, has found a consistent association between non-profit ownership and higher quality of care.14,15 The principal hypothesized mechanism for this association is that non-profit facilities have higher direct care staffing levels,5,14,15 which in turn are associated with better process16 and outcome measures.17,18 Research on nursing home quality in Canada is in its infancy. There is little Canadian research on facility ownership and quality19-24 and no published Canadian research on complaints. Furthermore, health policy in many but not all jurisdictions appears to be moving toward increased contracting of residential care by health ministries to for-profit facilities.25

This study examines publicly available data in one Canadian province (Ontario) and one large health region (Fraser Health) in British Columbia (BC). Our study goals were to describe the frequency distribution and types of complaints; to describe the number of complaints per 100 beds per year by facility ownership, size and regulatory measures; and to analyze the association of facility ownership characteristics with complaints in each jurisdiction.

Methods

Complaints are described on the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care website as “the expression of dissatisfaction relating to the operation of a long-term care (LTC) home.”26 Complaints can be made at any time by a resident, family or member of the general public.27 Each concern reported in the complaint is followed up by a Ministry of Long-Term Care inspector to determine whether it is “verified.”28 During the period of the current study, nursing homes in Ontario were governed by three different sets of legislation.* Legislation covering for-profit and non-profit facilities (Nursing Homes Act, 1990) enshrined a duty to report suspected neglect. The complaints process for municipal and charitable facilities was covered by less formal ministry policy.

At the time of the study the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care stated that “verified complaints may result in an unmet standard/criteria or citation issued against the long-term care (LTC) home operator.”29 An unmet standard was a finding that a facility had not met one of the standards outlined in the Long-Term Care Homes Program Manual during the course of any Ministry inspection. This manual contained over 470 items and provided the policy link among the three pieces of legislation and a common set of standards and criteria. A citation against the facility is a more serious finding; in this case, the long-term care home operator is found to be in violation of the legislation or regulations governing that home.26

In BC, regulation of nursing homes is devolved to five geographically based health regions. Each region has a Community Licensing Office to which complaints can be directed in writing or by phone. The licensing officer then follows up on the complaint to decide whether it is substantiated and to determine its seriousness. Although the process of determining whether a complaint is founded appears to be similar between jurisdictions, for the purpose of clarity we have retained the specific terminology used by each jurisdiction: “verified” complaints in Ontario and “substantiated” complaints in Fraser Health.

The regulatory measures used in the BC system are risk ratings and inspection violations. A risk rating is a score assigned to each facility on the basis of a formal set of criteria. Risk ratings provide a method for inspectors to determine the intensity of monitoring of a given facility. Risk ratings take into consideration a wide range of factors related to complaints: staffing, management and staff supervision, facility physical environment, policies and inspection results.30 Inspection violations are violations of the Community Care and Assisted Living Act Residential Care Regulations.31

Study population and data sources

Our study population included all licensed facilities providing care to the elderly in Ontario in 2007/08 and in one large health region (Fraser Health) in BC from 2004 to 2008. The study periods for these two jurisdictions were determined by the years for which data were posted and available at the time we began our study.

Data were extracted from a number of sources. Ontario data on verified complaints, unmet standards, citations, facility ownership and size were taken from a publicly available website posted by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.32 These data were available for 1 year only (1 July 2007 to 30 June 2008). Data on chain affiliation were provided by one of the study co-authors (Stocks-Rankin), who collected this information as part of a master’s thesis on ownership in Ontario’s long-term care facilities.33

Unlike in Ontario, complaints data in British Columbia are not routinely released by the Health Authorities. However, these data were available on a website posted by one of Vancouver’s daily newspapers (The Vancouver Sun), which obtained access through a Freedom of Information request to the Fraser Health Authority. The newspaper then constructed a website to make these data publicly available.34 The complaints data from this source represent the 4-year period from 1 April 2004 to 31 March 2008. The BC data on facility ownership and size were obtained using the same methods described in previous research.22

For both jurisdictions, complaints are posted in such a way that one cannot know whether one individual is lodging several complaints or multiple individuals are lodging one complaint. The study was reviewed and approved by the UBC Research Ethics Board.

Data measures

The complaint categories established by each regulatory body were used to classify complaint types. Although these are not exactly the same across jurisdictions, both classifications give the reader an idea of the general themes that were reflected in the complaints.

Our main outcome measure was complaints per 100 beds per year, as calculated by dividing the number of complaints for a given year in a given facility by the total number of beds in that facility multiplied by 100. We assumed that occupancy in both jurisdictions was full, such that complaints per 100 beds represented a reasonable surrogate measure of complaints per 100 nursing home residents. This assumption was based on lengthy wait times for residents to be admitted to residential care in Ontario35 and bed occupancy rates of 98.5% to 99.1% in Fraser Health over those periods (Heather Cook, Executive Director, Residential Care & Assisted Living Program, Hope Community & Fraser Canyon Hospital, Fraser Health Authority; personal communication, 2011 Oct 28). In Fraser Health, for the descriptive portion of the analysis only, we assumed that the rate of complaints was spread evenly across the 4-year period and divided the total complaints per 100 beds by 4.

In Ontario, we were able to examine only verified complaints, as data on the total number of lodged complaints were not available. In Fraser Health, both substantiated and total complaints were available. The latter includes substantiated and unsubstantiated complaints, complaints for which data were insufficient, complaints outside the licensing mandate, and complaints for which data were not available. We decided to examine this measure (total complaints), since there may be considerable challenges to the substantiation of complaints in this population.12,36

Our main variable of interest was facility ownership. Ownership in Ontario was classified into 5 groups: for-profit chain affiliation (defined as a for-profit facility with more than one site), for-profit single-site; non-profit; charitable (defined as a non-profit facility with charitable status); and public (defined as a facility owned and operated by a municipality). The Ontario non-profit facility classifications were those posted on the publicly available website. Ownership in Fraser Health was classified into 2 groups (for-profit and non-profit) in view of the small number of publicly owned facilities (n = 2) and the absence of data for chain affiliation.

We also examined the frequency of complaints in relation to facility size, as measured by bed numbers, and the regulatory measures for each jurisdiction posted along with the complaints data for the same period. In Ontario, these data pertained to unmet standards and citations. In Fraser Health, they pertained to inspection violations and facility risk ratings. All regulatory measures were dichotomized into observations falling at or below the mean or median versus all other observations. The median value was used as the cutoff if the standard deviation was greater than the mean; otherwise, the mean value was used as the cutoff. Risk ratings, available for 1 year only in Fraser Health, were also dichotomized into high and medium versus low risk. We further examined the distribution of complaints by year for Fraser Health.

Data analysis

First, we described the frequency distribution of complaints over the study periods. We then described the types and frequency of complaint categories. Next, we explored differences in the distribution of complaints per 100 beds per year by facility size, ownership, and other regulatory measures. One would expect there to be some correlation of complaints with other regulatory measures, given that the former is a trigger for more frequent inspections. However, since regulatory measures encompass a broader range of factors beyond complaints, we wanted to describe the distribution of complaints in relation to these measures.

All analyses were done at the facility level. In view of the high proportion of facilities with no complaints (over-dispersion of complaints data), we used negative binomial regression analysis to examine the effect of facility ownership on frequency of complaints. Facility ownership was our principal variable of interest. Facility size and year, the 2 other available variables, were entered concurrently with facility ownership as potentially confounding variables. Covariates were then dropped if their significance in the adjusted model was greater than p = 0.05 and their exclusion did not appear to influence the effect estimates for ownership (confounding effect). Standard errors were adjusted for the Fraser Health models to account for repeated measures of the same facilities over the 4-year period. SAS version 9.2 was used to run the analyses.

Results

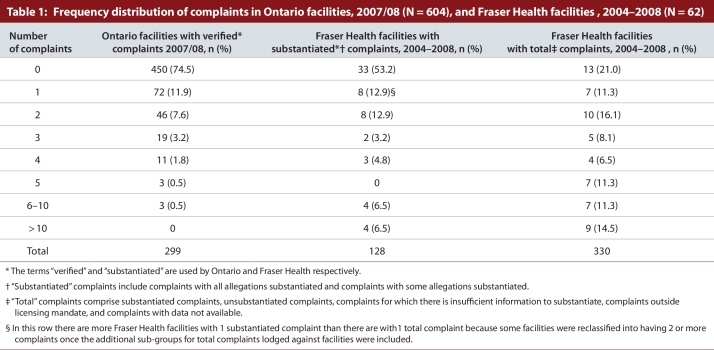

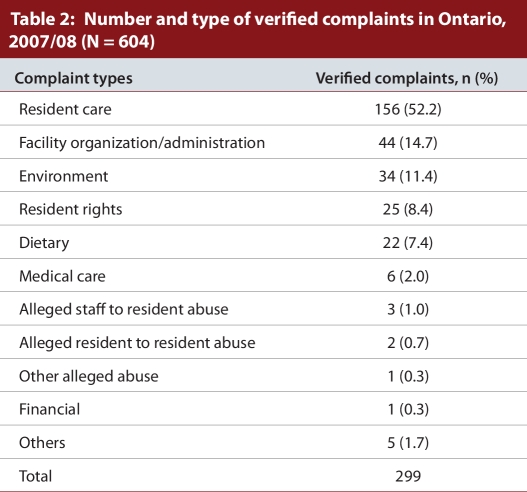

There were a total of 604 facilities in Ontario and 299 verified complaints in 2007/08. Twenty-five percent of the facilities accounted for all complaints, and almost three-quarters of facilities had no complaints (Table 1). The most frequent complaint category was resident care (n = 156, 52.2%), followed by facility organization and/or administration (n = 44, 14.7%) (Table 2). Just over 1 in 10 complaints related to the facility environment (n = 34, 11.4%) and fewer than 1 in 10 (n = 22, 7.4%) were complaints about the food (Table 2). A small number related to abuse (n = 6, 2.0%). A mean of 0.45 (standard deviation [SD] 1.10) verified complaints were received per 100 beds per year in Ontario (data not shown).

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of complaints in Ontario facilities, 2007/08, and Fraser Health facilities , 2004–2008

Table 2.

Number and type of verified complaints in Ontario, 2007/08

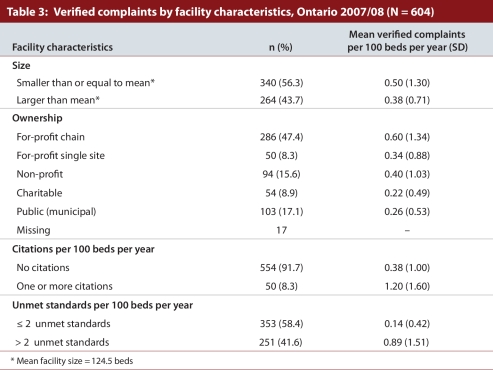

In Ontario, the mean number of verified complaints per 100 beds per year was higher in facilities found to have more than the median of 2 unmet standards as compared with those with 2 or fewer unmet standards 0.89 (SD 1.51) versus 0.14 (SD 0.42) (Table 3). The mean number of verified complaints per 100 beds per year were also higher in facilities with 1 or more citations as compared with facilities with no citations, 1.20 (SD 1.60) versus 0.38 (SD 1.00).

Table 3.

Verified complaints by facility characteristics, Ontario 2007/08

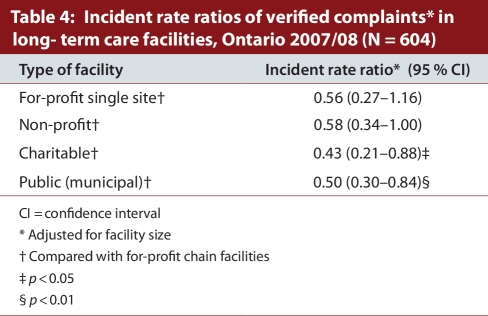

Over one-half of all Ontario facilities were for-profit (n = 336). Of these, the majority (n = 286) were part of a chain (Table 3). The mean (SD) number of complaints per 100 beds per year was 0.60 (1.34), 0.34 (0.88), 0.40 (1.03), 0.22 (0.49) and 0.26 (0.53) in Ontario’s for-profit chain, for-profit single-site, non-profit, non-profit charitable and public facilities respectively. Compared with for-profit chain facilities, the adjusted incident rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of complaints were 0.56 (0.27–1.16), 0.58 (0.34–1.00), 0.43 (0.21–0.88), and 0.50 (0.30–0.84) for for-profit single site, non-profit, charitable and public facilities respectively after controlling for facility size (Table 4).

Table 4.

Incident rate ratios of verified complaints in long-term care facilities, Ontario 2007/08

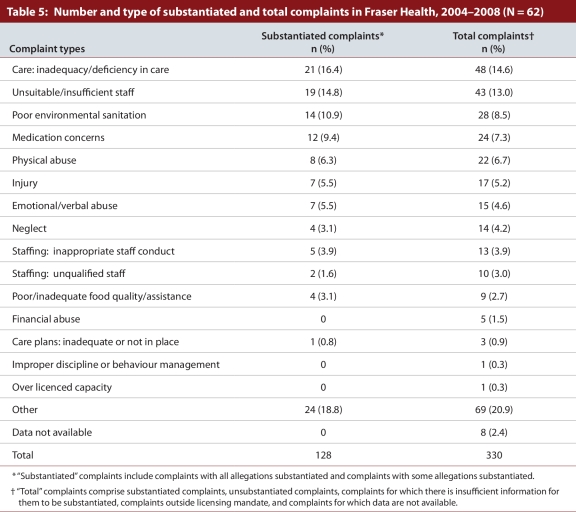

There were a total of 62 facilities in Fraser Health and 330 total complaints between 1 April 2004 and 31 March 2008 (Table 1). Approximately 50% of the facilities (N = 29) accounted for all the substantiated complaints, and half of facilities had no complaints (Table 1). The mean and SD for substantiated and total complaints per 100 beds per year in Fraser Health were 0.78 (1.63) and 1.81 (2.47) respectively, making a substantiation rate over that period of 43% (data not shown). As in Ontario, most complaints in Fraser Health related to resident care (Table 5). Mean substantiated and total complaints in Fraser Health showed some variation across years, with a trend of increasing complaints per 100 beds over the 4-year period (data not shown).

Table 5.

Number and type of substantiated and total complaints in Fraser Health, 2004–2008

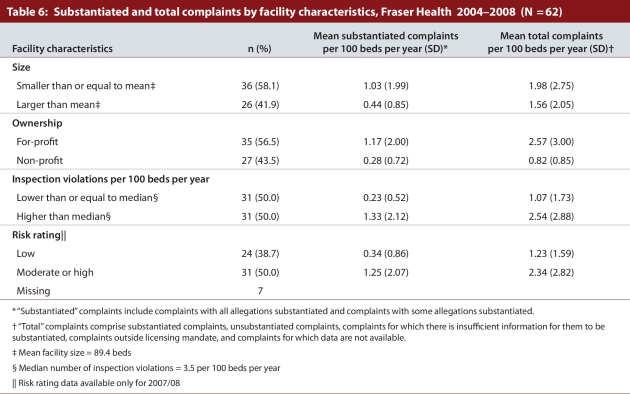

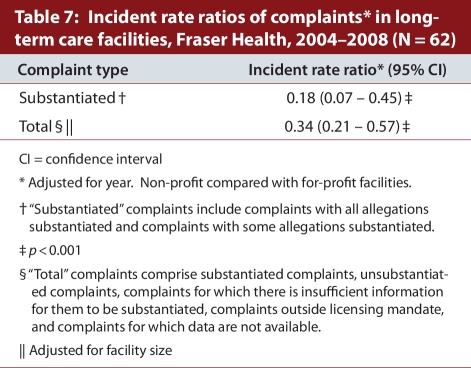

Fifty-seven percent of nursing homes in Fraser Health (n = 35) were for-profit facilities. The mean number of substantiated complaints per 100 beds per year was 1.17 (SD 2.00) and 0.28 (SD 0.72) in Fraser Health’s for-profit and non-profit facilities respectively. The mean number of substantiated complaints per 100 beds per year was lower in facilities with a lower rate of inspection violations: 0.23 (SD 0.52) versus 1.33 (SD 2.12). Complaints per 100 beds per year were also lower in facilities with a low-risk rating as compared with facilities with a moderate- or high-risk rating (Table 6). In Fraser Health, adjusted incident rate ratios of substantiated complaints and total complaints in non-profit facilities were 0.18 (CI 0.07–0.45) and 0.34 (0.21–0.57) respectively when compared with for-profit facilities (Table 7) after controlling for year and/or facility size.

Table 6.

Substantiated and total complaints by facility characteristics, Fraser Health 2004–2008

Table 7.

Incident rate ratios of complaints in long-term care facilities, Fraser Health, 2004–2008

Discussion

This study found that, compared with for-profit chain facilities in Ontario, non-profit, charitable and public facilities had a one-and-a-half to two-and-a-half times lower chance of receiving a verified complaint (Table 3). In Fraser Health, non-profit facilities had a 3 to 4 times lower chance of receiving a complaint in comparison with for-profit facilities for total and substantiated complaints respectively (Table 6).

Although further research using more comprehensive data is necessary, these findings suggest consistency with the US literature. In a 5-year examination of complaints in all US states, Stevenson12 found that for-profit facilities had an almost two-fold greater chance of receiving a complaint compared with non-profit facilities and that chains had a significantly higher rate of complaints compared with non-chain facilities. Harrington and colleagues5 also found that for-profit investor ownership predicted 0.679 additional “deficiencies” (a US regulatory measure similar to unmet standards), and chain ownership an additional 0.633 deficiencies per facility compared with non-profit facilities.

One interesting finding in Ontario is that non-profit, single-site facilities demonstrate higher complaint rates in comparison with public and charitable facilities. This diversity of performance between public and non-profit groups has been described previously in Canadian research on ownership and quality in nursing home populations. One study found that BC hospitalization rates for care-sensitive conditions in publicly owned or hospital-based facilities were significantly lower than in both for-profit and non-profit single-site facilities.22 A more recent study from British Columbia suggested that these differences may be related to the higher staffing levels in publicly owned facilities as compared with both for-profit and non-profit single-site facilities.23

The rate of verified/substantiated complaints overall appears to be lower in Canada than in the United States, where the national average number of substantiated complaints was 4.3 per 100 residents.12 (The corresponding rate was 0.45 and 0.78 per 100 beds in Ontario and Fraser Health respectively.) This may be because US consumers truly experience a lower quality of care than their Canadian counterparts; however, such differences across jurisdictions are more likely to reflect differences in regulatory systems than differences in quality per se.12 Moreover, even within the United States the annual number of complaints per 100 beds ranged from a low of 0.6 per 100 beds in South Dakota to a high of 16.5 in Washington.12 Such variation underscores that, although complaints have the potential to be a useful additional measure of quality of care, variation in complaints is best examined for facilities within the same regulatory jurisdiction rather than between jurisdictions that may have very different contexts.12

Similarly, the somewhat higher rate of complaints seen in Fraser Health in comparison with Ontario is more likely a reflection of jurisdictional differences between the 2 provinces in the complaints process rather than of quality differences per se. Both provinces now require, by law, a Residents’ Bill of Rights to be posted in a visible place in all facilities, and both provinces require facilities, at the time of admission, to advise residents and their representatives about the processes available for the expression of concerns, including how to lodge a formal complaint. However, such legislation has come into force in both jurisdictions only in the last 2 years. Unmeasured jurisdictional differences in the ease of lodging complaints, public awareness, and the confidence of complainants are all factors that may influence the frequency of complaints. Furthermore, even within jurisdictions, some facilities may do a more thorough job of educating residents and families about complaints, resulting in intra-jurisdictional variation that is not reflective of quality.

Another interesting difference in our findings relative to those of US studies is the frequency of complaints of abuse against residents. Whereas this was the second most common complaint in US nursing homes,12,36 complaints of abuse were relatively rare in both Canadian jurisdictions studied. However, again, given the lack of a common complaints classification system across jurisdictions, it is difficult to know how to interpret this difference.

Fewer than half of all complaints lodged in Fraser Health were substantiated (43%). This is only slightly higher than the 38% substantiation rate in the United States12 and underscores the challenge to regulators to corroborate complaints in this population. Reported events are often unwitnessed, and cognitively impaired residents may have difficulty recalling the details of a given experience. Despite the low substantiation rate, in view of the power imbalance that families and residents may face when lodging a complaint, there is no reason to believe that the majority of complaints made are unfounded.

The finding that the frequency of complaints is higher in facilities with higher rates of citations and inspection violations is not surprising, given that complaints trigger further investigations, thereby increasing the likelihood of regulatory findings and/or sanctions. This is consistent with US findings that the number of complaints during one 3-month period was positively associated with deficiencies identified by inspections in the subsequent period.12,36 However, because of the cross-sectional nature of our study, it is also possible that facilities with poorer performance on other regulatory measures are also more likely to receive complaints.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, we were unable to adjust for resident case mix. Although one study of nursing homes in Massachusetts found no effect of case mix on complaints, it would nonetheless be important for future research to adjust for this.36 Although complaints should theoretically be independent of case mix, it is possible that such lack of adjustment may result in unintended bias. For example, a disproportionate number of residents with dementia in non-profit and public facilities who may be less likely to lodge complaints could produce a spurious association between for-profit facilities and a higher complaints rate. Moreover, because of this limitation, we cannot definitively conclude that our findings are consistent with those of US studies in which facility case mix adjustors were used. We were also unable to measure the degree to which families are involved in visiting residents and the presence of family councils, both of which are known to influence the frequency of complaints.12 Future research using more comprehensive quality-of-care data, longitudinal data sets, case-mix adjustors and qualitative interviews with complainants is needed to fully understand the causes of complaints.

A second limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study. For Ontario, we were restricted to 1 year of data only and, for BC, complaints data were available from one health region only. Third, we were unable to link complaints data to other quality measures. Research in the United States has demonstrated an association of higher complaint rates with lower care aide staffing levels and higher rates of pressure sores,36 and it would be important to assess the degree to which complaints correlate with these and other care process and outcome quality measures in the Canadian context. Fourth, our study did not distinguish between user-pay facilities and for-profit facilities whose main income source is from publicly funded beds. Although the former group accounted for a relatively small proportion of all long-term care beds, there may well be important distinctions between the care quality in such facilities. Fifth, by measuring complaints per bed as a surrogate for complaints per residents, we were assuming full occupancy at all times. Although we believed this to be a reasonable assumption, given long wait times for admission to nursing homes in both jurisdictions,35 it is possible that this assumption may not be equally true across facilities of all ownership categories and may have biased our results.

Finally, there are a number of potential sources of unmeasured bias in such a study. There may be reporting bias in Ontario, where at the time of the study the legislated duty to report complaints in for-profit and non-profit facilities may have resulted in disproportionally higher rates of reporting of complaints from these facilities in comparison with municipal and charitable homes. Also in Ontario, both charitable and municipal homes tend to have longer wait lists than for-profit facilities; families, after waiting a long time to get into these facilities, may be more reluctant to complain.

Although a majority of facilities in both jurisdictions had no substantiated complaints, their absence in a facility, like the absence of other indicators of poor quality, such as pressure ulcers and restraint use, “does not equal good care.”37 (p 1377) Nonetheless, unlike other indicators measured through inspection reports or administrative data, complaints are consumer driven, can occur at any time, and represent an independent, additional measure to the clinical process and outcome measures more traditionally thought to reflect quality. There is also a growing trend among governments to make complaints data publicly available, both to inform consumers and to improve accountability.

Overall, our finding that public and non-profit facilities have a lower frequency of complaints suggests consistency with the growing body of literature demonstrating poorer performance on care process and outcome measures associated with for-profit delivery of residential long-term care. Results should be interpreted with some caution until further research using more comprehensive data linked to other quality measures, with adequate case mix adjustment, confirms these findings.

The form of ownership that best supports a higher quality of care is a relevant policy question, given the upcoming challenge for all jurisdictions to expand specialized seniors housing and on-site care to meet the needs of the aging population. The difference in consumer complaints by ownership adds further empirical evidence from the Canadian context to inform this discussion.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Alan Wong, who assisted with data extraction from the public websites; Pat Armstrong, Professor of Sociology and Women’s Studies, York University, who assisted with interpreting the Ontario data; Greg Ritchey, Regional Manager, Community Care Facilities Licensing, Vancouver Coastal Health, who assisted in helping us to understand how regulation works in British Columbia; Jennifer Quan, second-year medical student at the University of British Columbia, who contributed to classifying the complaint types and reviewing the literature; Whitney Berta, Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, who provided helpful assistance in the early phases of the study; and the librarians of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia, who assisted with literature searches; Chad Skelton, Vancouver Sun journalist, who constructed the publicly accessible nursing home database from which our study drew the BC data and who assisted us with understanding the process of data access.

Biographies

Margaret J. McGregor, MD, MHSc, is a Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of Family Practice, University of British Columbia, a Research Associate at the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute Centre for Clinical Epidemiology & Evaluation, and a Research Associate at the UBC Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Marcy Cohen, MEd, is a Research Associate at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, BC Office, Vancouver.

Catherine-Rose Stocks-Rankin, MSc, is a PhD Candidate at the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Michelle B. Cox, MSc, and

Kia Salomons, MSc, are Research Associates in the Department of Family Practice, University of British Columbia.

Kimberlyn M. McGrail, PhD, is Associate Director of the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research and Assistant Professor of the School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia.

Charmaine Spencer, LLM, is a Research Associate at Simon Fraser University Department of Gerontology and Gerontology Research Centre, Vancouver.

Lisa A. Ronald, MSc, is a PhD Candidate at McGill University, Montréal, Quebec, a Research Associate in the Department of Family Practice, University of British Columbia, and a Research Associate with the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute Centre for Clinical Epidemiology & Evaluation, Vancouver.

Michael Schulzer, MD, PhD, is a Professor Emeritus, Department of Statistics, University of British Columbia.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: This study was supported by a grant from the Vancouver General Hospital Department of Family Practice, the UBC Family Practice Division of Geriatrics, and a UBC Summer Student Research Program Award (2009). Dr. McGregor is supported by a Community Based Clinician Investigator Award funded by the UBC Family Practice Division of Geriatrics and the UBC Centre for Health Services and Policy Research.

Margaret J. McGregor conceived the project, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, oversaw the data collection and analysis, and participated in all phases of the writing of the manuscript. Marcy Cohen conceived the project and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. Catherine Stocks-Rankin contributed to the data collection and the writing and editing of the manuscript. Michelle B. Cox and Kia Salomons contributed to the data analysis and to the writing and editing of the manuscript. Kim M. McGrail, Charmaine Spencer and Lisa A. Ronald contributed to data interpretation and the writing and editing of the manuscript. Dr. Michael Schulzer supervised the data analysis and assisted with the manuscript editing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Michelle B. Cox performed the statistical analysis under the supervision of Dr. Michael Schulzer. Dr. McGregor is acting as the guarantor of the article.

Nursing Homes Act, 1990 (for-profit and non-profit facilities); Charitable Institutions Act, 1990 (faith-based and ethnic charitable facilities); Homes for the Aged and Rest Homes Act, 1990 (municipal homes).

References

- 1.Cohen M, Murphy J, Nutland K, Ostry A. Continuing care renewal or retreat? BC residential and home health care restructuring 2001–2004. Vancouver: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives–BC Office; 2005. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frohlich N, De Coster C, Dik N. Estimating personal care home bed requirements. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy; 2002. http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/pch2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharkey S. People caring for people. Impacting the quality of life and care of residents of long-term care homes. A report of the independent review of staffing and care standards for long-term care homes in Ontario. Ontario Government; 2008. May, http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/pub/ministry_reports/staff_care_standards/staff_care_standards.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CBC News. “Horror stories” from Ontario nursing homes worry ombudsman. 2008. Jul 3, http://www.cbc.ca/canada/toronto/story/2008/07/03/nursing-homes.html.

- 5.Harrington C, Woolhandler S, Mullan J, Carrillo H, Himmelstein D U. Does investor ownership of nursing homes compromise the quality of care? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1452–1455. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.9.1452. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/11527781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerrison S H, Pollock A M. Regulating nursing homes: Caring for older people in the private sector in England. BMJ. 2001 Sep 8;323(7312):566–569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7312.566. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.323.7312.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter K S. The best of care: getting it right for seniors in British Columbia (Part 1). Public Report No. 46. British Columbia: Office of the Ombudsperson; 2009. http://www.bccare.ca/pdf/Ombudsperson%27s%20Report%20-%20Dec%2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marin A. Investigation into the Ministry’s monitoring of Long-Term Care Homes. 2010. http://www.ombudsman.on.ca/Files/sitemedia/Documents/Investigations/SORT%20Investigations/ltc-for-web-en-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Protecteur du Citoyen–Assemblée nationale Québec. Rapport annuel 2009–2010. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec; 2010. http://www.protecteurducitoyen.qc.ca/?id=27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschman A O. Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirth Richard A, Banaszak-Holl Jane C, Fries Brant E, Turenne Marc N. Does quality influence consumer choice of nursing homes? Evidence from nursing home to nursing home transfers. Inquiry. 2003;40(4):343–361. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_40.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson David G. Nursing home consumer complaints and quality of care: a national view. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):347–368. doi: 10.1177/1077558706287043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabowski David C. Consumer complaints and nursing home quality. Med Care. 2005;43(2):99–101. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comondore Vikram R, Devereaux P J, Zhou Qi, Stone Samuel B, Busse Jason W, Ravindran Nikila C, Burns Karen E, Haines Ted, Stringer Bernadette, Cook Deborah J, Walter Stephen D, Sullivan Terrence, Berwanger Otavio, Bhandari Mohit, Banglawala Sarfaraz, Lavis John N, Petrisor Brad, Schünemann Holger, Walsh Katie, Bhatnagar Neera, Guyatt Gordon H. Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009 Aug 4;339:b2732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2732. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/19654184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillmer Michael P, Wodchis Walter P, Gill Sudeep S, Anderson Geoffrey M, Rochon Paula A. Nursing home profit status and quality of care: is there any evidence of an association? Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(2):139–166. doi: 10.1177/1077558704273769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnelle John F, Simmons Sandra F, Harrington Charlene, Cadogan Mary, Garcia Emily, Bates-Jensen Barbara M. Relationship of nursing home staffing to quality of care. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(2):225–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00225.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/15032952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castle Nicholas G, Anderson Ruth A. Caregiver staffing in nursing homes and their influence on quality of care: using dynamic panel estimation methods. Med Care. 2011;49(6):545–552. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fbca9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bates-Jensen Barbara M, Schnelle John F, Alessi Cathy A, Al-Samarrai Nahla R, Levy-Storms Lené. The effects of staffing on in-bed times of nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):931–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berta Whitney, Laporte Audrey, Valdmanis Vivian. Observations on institutional long-term care in Ontario: 1996-2002. Can J Aging. 2005;24(1):71–84. doi: 10.1353/cja.2005.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bravo G, Dubois M F, Charpentier M, De Wals P, Emond A. Quality of care in unlicensed homes for the aged in the eastern townships of Quebec. CMAJ. 1999 May 18;160(10):1441–1445. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/10352633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doupe Malcolm, Brownell Marni, Kozyrskyj Anita, Dik Natalia, Burchill Charles, Dahl Matt, Chateau Dan, De Coster Carolyn, Hinds Aynslie, Bodnarchuk Jennifer. Using administrative data to develop indicators of quality care in personal care homes. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy; 2006. http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/pch.qi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGregor Margaret J, Tate Robert B, McGrail Kimberlyn M, Ronald Lisa A, Broemeling Anne-Marie, Cohen Marcy. Care outcomes in long-term care facilities in British Columbia, Canada. Does ownership matter? Med Care. 2006;44(10):929–935. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223477.98594.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGregor M J, Tate R B, Ronald L A, McGrail K M, Cox M B, Berta W, Broemeling A M. Staffing in long-term care in British Columbia, Canada: A longitudinal study of differences by facility ownership, 1996–2006. Health Reports. 2010;21(4):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro E, Tate R B. Monitoring the outcomes of quality of care in nursing homes using adminstrative data. Can J Aging. 1995;14(4):755–768. doi: 10.1017/S0714980800016445. http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0714980800016445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGregor M J, Ronald L A. Residential long-term care for Canadian seniors: non-profit, for-profit or does it matter? Report no. 14. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Government of Ontario. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Reports on long-term care homes. Glossary of terms. 2010. Nov 23, [accessed 2011 Jun 20]. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/program/ltc/28_pr_glossary.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meadus J E. Complaints in long term care homes. Advocacy Centre for the Elderly. 2009. http://www.advocacycentreelderly.org/appimages/file/Complaints_in_LTC_-_2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Government of Ontario. Long Term Care Home Act, 2007. Ont Reg. 79/10. [accessed 2011 Jun 20]. http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/regs/english/elaws_regs_100079_e.htm#BK121. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Government of Ontario. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Profile definitions. 2011. [accessed 2009-10-19]. http://publicreporting.ltchomes.net/en-ca/content/HomeProfile_bottom.htm#vc.

- 30.Government of British Columbia. Ministry of Health. The risk management approach for community care facilities licensing officers – Version 1. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Government of British Columbia. Ministry of Health. Community Care and Assisted Living Act. Residential Care Regulation. 2009. [accessed 2011 Jun 23]. http://www.bclaws.ca/EPLibraries/bclaws_new/document/ID/freeside/96_2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Senior’s care: long-term care homes. 2009. [accessed 2009 Feb 27]. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/program/ltc/15_facilities.html.

- 33.Stocks-Rankin C R. Who cares about ownership? A policy report on for-profit, not-for-profit and public ownership in Ontario long term care. Masters thesis. Edinburgh (UK): University of Edinburgh; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Care & attention [database of inspection information for daycares, long-term care facilities, group homes and other facilities] [accessed 2008 Jul 5];The Vancouver Sun. http://www2.canada.com/vancouversun/features/care/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bronskill S E, Carter M W, Costa A P, Esensoy A V, Gill S S, Gruneir A, Henry D A, Hirdes J P, Jaakkimainen R L, Poss J W, Wodchis W P. Aging in Ontario: an ICES chartbook of health services use by older adults. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2010. http://www.ices.on.ca/file/AAH%20Technical%20Report_Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevenson David G. Nursing home consumer complaints and their potential role in assessing quality of care. Med Care. 2005;43(2):102–111. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kane R L. Improving the quality of long-term care. JAMA. 1995;273(17):1376–1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.17.1376. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/doi/10.1001/jama.273.17.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]