Abstract

Background

The identification of health care professionals who are incompetent, impaired, uncaring or have criminal intent has received increasing attention in recent years. These individuals are often subject to disciplinary action by professional licensing authorities. To date, no national data exist for Canadian physicians disciplined for professional misconduct. We sought to describe the characteristics of physicians disciplined by Canadian professional licensing authorities.

Methods

We constructed a database of physicians disciplined by provincial licensing authorities during the years 2000 to 2009. Comparisons were made with the general population of physicians licensed in Canada. Data on demographic characteristics, type of misconduct and penalty imposed were collected for each disciplined physician.

Results

A total of 606 identifiable physicians were disciplined by their professional college during the years 2000 to 2009. The proportion of licensed physicians who were disciplined in a given year ranged from 0.06% to 0.11%. Fifty-one of the disciplined physicians committed 64 repeat offences, accounting for a total of 113 (19%) offences. Most of the disciplined physicians were independent practitioners (99%), male (92%) and trained in Canada (67%). The most common specialties of physicians subject to disciplinary action were family medicine (62%), psychiatry (14%) and surgery (9%). For disciplined physicians, the average number of years from medical school graduation to disciplinary action was 28.9 (standard deviation [SD] = 11.3). The 3 most frequent violations were sexual misconduct (20%), failure to meet a standard of care (19%) and unprofessional conduct (16%). The 3 most frequently imposed penalties were fines (27%), suspensions (19%) and formal reprimands (18%).

Interpretation

A small proportion of registered physicians in Canada were disciplined by their medical licensing authorities. Sexual misconduct was the most common disciplined offence. The standardization of provincial reporting along with the creation of a national database of physician offenders would facilitate more comparable public reporting as well as further research and educational initiatives.

The identification of health care professionals who are incompetent, delinquent or have criminal intent has received increasing attention in scholarly publications and the lay press in recent years.1-9 Although these individuals represent a small subset of practising physicians, increasing media attention in conjunction with new forms of information technology that enable faster dissemination of information about physicians has made such cases highly visible to the public.10

In Canada, provincial authorities have the ability to police and regulate the quality of medicine through disciplinary action. Provincial legislation provides the legal basis for medical licensing authorities known as the Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons (CPSs; Appendix A). The provincial Colleges and the territorial regulatory authorities provide the structure for the governance, discipline, and accountability of physicians in Canada. In addition, these authorities provide patients with an alternative to civil litigation.1

Information regarding physician-related complaints is usually confidential unless it leads to a formal disciplinary hearing. Across the provinces and territories, varying jurisprudence establishes the framework by which these authorities operate, and criteria for formal disciplinary hearings vary across the country. However, all complaints of patient negligence, professionalism and sexual abuse are considered serious matters and are usually dealt with by recourse to individual CPS regulatory policy. CPSs are mandated to record and make information about these cases public. However, information on disciplinary hearings and proceedings from the territorial licensing authorities (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon) are often not transparent or publicly available.

The majority of research on physician negligence and incompetence relies on data from civil litigation and closed claims.1 The available literature on physician disciplinary action through licensing authorities focuses mainly on data from state medical boards in the United States. Violations include, but are not limited to, failure to meet a standard of care, fraud, sexual misconduct, prescribing violations and incompetence. These studies generally agree that a lack of board certification, being male and being in practice for a long period of time may increase one’s risk for disciplinary action. 2-7 Although similar data are available through online provincial sources, to date there are no amalgamated peer-reviewed data examining physicians disciplined in Canada.

Therefore, we sought to better understand the characteristics of physicians disciplined in Canada through a retrospective cohort study of physicians disciplined by provincial licensing authorities during the years 2000 to 2009.

Methods

Overview

We analyzed the publicly available data for all provincial medical licensing authorities in Canada. We studied all physicians disciplined from 2000 to 2009. We extracted data on the type of misconduct violation and the penalty imposed on each physician disciplined, as well as demographic variables. Comparisons were made with the total population of licensed physicians in Canada.11-12

Identification of disciplined physicians

Canadian physicians disciplined during the years 2000 to 2009 were identified by reviewing all available online monthly publications from each CPS. Physicians who were either not named or for whom demographic details were insufficient were excluded from the primary analysis. Online data for the years before 2007 were not available for New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador. In addition, online data for the years before 2002 were not available for Alberta. Data for all other provinces were complete for the years 2000 to 2009.

Descriptive data and sources

Demographic information collected for each physician included: sex; type of practice licence (independent practice v. educational licence); medical school from which the physician graduated; and medical specialty. We calculated total years of practice as the total number of years between obtaining a medical degree and the disciplinary action. Specialties were grouped into categories: anesthesiology; family medicine (and general practice); internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology; pediatrics; psychiatry; radiology; surgery; and other specialties.7

Physician information that was not available through the disciplinary summaries was obtained either through provincial licensing website databases or from the Canadian Medical Directory for the years 1970 through 2008.13 If we could not find data on physicians, we directed inquiries about their demographic characteristics to the CPSs themselves. A total of three requests were made directly to CPSs, who responded in each case with the information requested.

Classification of violations and disciplinary actions

Violations and disciplinary actions were grouped on the basis of categories modified from previous studies.6,7 Each published disciplinary action was reviewed and categorized into the following groups: conviction of a crime; fraudulent behaviour/prevarication; inappropriate prescribing; mental illness; failure to meet a standard of care; use by the physician of drugs or alcohol; sexual misconduct; unprofessional conduct; unlicensed activity/breech of registration terms; miscellaneous violations; and unknown/unclear violations. Miscellaneous violations mainly included violations involving breaches of confidentiality, improper disclosure to patients and improper handling or maintenance of medical records. In addition, information regarding the penalties that were imposed on these physicians were grouped into the following categories: licence revocation; licence surrender; suspension; licence restriction; mandated retraining/education/course/assessment; mandated psychological counselling and/or rehabilitation; formal reprimand; fine/cost repayment; other actions. We also kept detailed information regarding fines and/or costs of medical proceedings that had to be paid by disciplined physicians as a term of their penalty.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the frequencies and proportions of each physician characteristic, violation and penalty category variable, as well as the means of total years of practice. We calculated the median and interquartile range (IQR) for fines, suspension length and time between first and second offences for repeat offenders. We also examined the proportion of physicians disciplined in 2007 and 2008, since we were able to access a complete dataset for all provinces for those years. Statistics on the total population of independent practitioners statistics was compiled using annual physician census data from the Canadian Institute of Health Information. Statistics on the number of resident physicians were added using CAPER (Canadian M.D. Post-Education Registry).12 The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board of St. Michael’s Hospital (Toronto, Ont.).

Results

From 2000 to 2009, a total of 606 identifiable physicians were disciplined in Canada (Table 1). A further 23 physicians who were disciplined but not named in the databases available to us were excluded from our primary analysis. Approximately 51 (9%) disciplined physicians were subject to more than one disciplinary action at separate times: 42 physicians were disciplined 2 times, 7 physicians 3 times and 2 physicians 4 times, accounting for a total of 113 (19%) offences. The median time between first and second offences was 2 years (IQR 1–4 years).

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics of disciplined physicians in Canada from 2000 to 2009

The majority of physicians disciplined in Canada were independent practitioners (99%), male (92%) and graduates of a Canadian medical school (67%). In the general Canadian physician population, the corresponding proportions are as follows: independent practitioners, 89%; males, 68%; and Canadian medical school graduates, 77%. The most common specialties of physicians subject to disciplinary action were family medicine (62%), psychiatry (14%) and surgery (9%). These specialties comprise 51%, 7% and 10% of the total physician population in Canada, respectively. The mean (SD) number of years of practice before conviction was 28.9 (11.3) years.

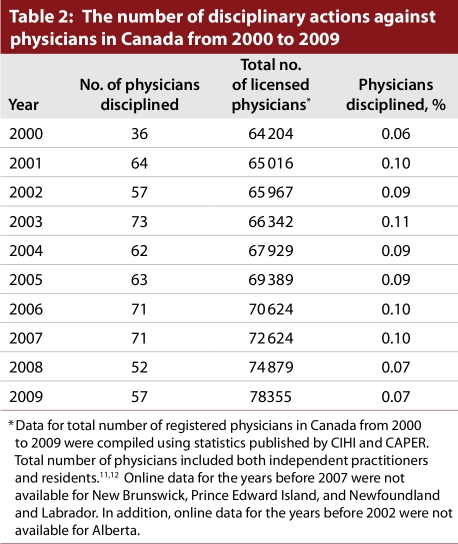

The proportion of physicians disciplined in Canada each year was small, ranging from 0.06% to 0.11% (Table 2). For the years 2007 and 2008, the proportion of disciplined physicians was well distributed among different provinces, ranging from 0.08% to 0.26%. The highest proportions of physicians were disciplined in British Columbia (0.25%) and, collectively, in the Eastern provinces (0.26%).

Table 2.

The number of disciplinary actions against physicians in Canada from 2000 to 2009

A total of 852 different violations were committed by all physicians who were disciplined (Table 3). The 3 most frequent violations—sexual misconduct (20%), standard-of-care issues (19%) and unprofessional conduct (16%)—accounted for more than half of all offences. Greater than half of all repeat offences were also in the realm of sexual misconduct (20%), standard-of-care issues (20%) and unprofessional conduct (14%).

Table 3.

The types of physician violations disciplined in Canada from 2000 to 2009

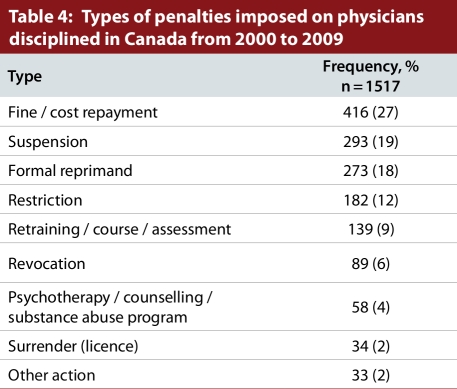

A total of 1517 penalties were imposed on the disciplined physicians (Table 4). The three most frequent penalties were being fined (27%), getting a suspension (19%) or being formally reprimanded (18%); together, these penalties represented more than two thirds of all penalties imposed. Licence revocation accounted for only 6% of the total penalties imposed. Of the repeat offences, licence revocation accounted for only 10% of total penalties. Similarly to the penalties for overall offences, being fined (26%), receiving a formal reprimand (16%) or being suspended (13%) accounted for the majority of repeat offence penalties.

Table 4.

Types of penalties imposed on physicians disciplined in Canada from 2000 to 2009

Detailed suspension information was available for 287 (98%) of the 293 physicians who were suspended. The median suspension length was 4 months (IQR = 2–9 months). Detailed information on fines or cost repayment was available for 329 (79%) of the physicians who were required to pay fines or costs. The median fine/cost amount was $4000 (IQR $2500–$10 000).

Of the 23 physicians who were not included in the primary analysis, the most frequent violations were inappropriate prescribing (22%), sexual misconduct (17%), unprofessional conduct (17%), miscellaneous violations (17%) and failure to meet a standard of care (13%). Approximately 40% of these physicians were fined, and 35% of these physicians were required to undergo counselling. Only one of these physicians (4%) had his or her licence revoked, and 5 physicians (21%) had his or her licence to practise suspended.

Interpretation

We found that a small proportion of physicians were disciplined in Canada during the years 2000 to 2009. Compared with the general population of physicians in Canada, a higher proportion of those disciplined were male, had an independent practice licence, and were a graduate of an international medical school; the average time in practice before disciplinary action was 28.9 years. The majority of disciplined physicians practised in the specialties of family medicine and psychiatry, and these specialties were over-represented relative to their proportion in the Canadian physician population overall. Just under one-tenth of disciplined physicians were repeat offenders, but this group accounted for almost one-fifth of all offences.

These findings are similar to those of previous studies from the United States that examined the relationship of gender to disciplinary action.2-7 Kohatsu and colleagues7 reported that 91% of disciplined physicians were male. Similarly, Khaliq and associates6 showed that male physicians (p < 0.04) were more likely to be disciplined than their female counterparts. Taragin and coauthors14 proposed that a number of differences between male and female physician practice styles, including differences in physician–patient interactions, contribute to the fact that male physicians were 3 times as likely to be in a high-claims malpractice category than their female counterparts. Specifically, they suggested that women communicate more effectively with patients and that this, in itself, is responsible for a lower rate of malpractice claims.

Our data indicate that most physicians subject to disciplinary action in Canada were trained in Canada. However, the proportion of disciplined physicians who were trained at international medical schools is larger than proportion of the total physician population who trained abroad. These findings corroborate other findings that between 26% and 30% of disciplined physicians are international medical graduates.6-7

Previous work also indicates that physicians for whom a strong therapeutic alliance is an important feature of care (such as family physicians and psychiatrists) have a higher predisposition to being disciplined. Indeed, Morrison and Wickersham2 showed that, in comparison with controls matched by location, disciplined physicians were more likely to be involved in direct patient care. Furthermore, Dehlendorf and Wolfe8 showed that physicians practising in the fields of psychiatry, family practice, general practice and obstetrics and gynecology were more likely to be disciplined for sex-related offenses when compared with all physicians. It may be that prolonged psychosocial interaction with patients can predispose physicians in these specialties to engage in inappropriate behaviour and thus increase their risk of being disciplined. However, it should be noted that other specialties involved in developing long-term physician–patient relationships (i.e., subspecialties of internal medicine) do not seem to have increased rates in comparison with others.6,8

There is a difference in the proportions of physicians disciplined in Canada and in the United States. According to data from the Federation of State Medical Boards,15-17 the proportion of physicians disciplined in the United States from 2000 to 2009 (0.39% to 0.53%) is almost 4 times that of Canada. There are a number of possible explanations for this phenomenon. First, major differences in licensure policy in the United States make disciplinary action against physicians more commonplace. In fact, since the 1980s the number of physicians disciplined yearly by state medical boards has increased significantly.18 Second, the traditionally more litigious culture of the United States encourages patients to pursue multiple forums for retribution for medical misconduct.1 Indeed, malpractice lawsuits are far more common in the United States than in Canada: 350% more suits are filed each year per person than in Canada.19 More research will be required to fully describe this phenomenon.

We did observe that the highest rates of disciplinary actions against Canadian physicians occurred in British Columbia and the Eastern provinces. However, given that we examined complete data for only a short period (2007–2008), a longer longitudinal study would be required to confirm these findings and to formally test for differences between provinces.

It is concerning that a large proportion of violations by Canadian physicians involved sexual misconduct, which is an egregious breach of public trust. As a proportion of offences by physicians, sexual misconduct is estimated to be lower in the United States than in Canada, accounting for between 3.1% and 10% of disciplinary actions.2,6-8,18 Perhaps sexual misconduct in the United States is disciplined outside of traditional medical licensure systems to a greater extent than in Canada. The reasons for this phenomenon remain speculative at best. However, despite a lack of consensus regarding how to educate medical trainees and physicians with regard to sexual boundaries,20-22 this finding may identify a need for greater attention to this critical topic within the medical education curricula – including, potentially, focusing on international medical graduates23 and continuing professional development.

It is also notable that provincial licensing authorities devote significant resources toward disciplining repeat physician offenders. Previous research in the United States corroborates the finding that a substantial fraction of previously disciplined physicians are subsequently disciplined at rates far higher than physicians with no discipline history. This indicates a possible need for greater monitoring of disciplined physicians and/or less reliance upon rehabilitative sanctions such as disciplinary action to promote and sustain positive change in behaviour.8,18

Although provincial authorities are mandated to record and publicly disseminate this information, there appears to be little uniformity in data collection and reporting processes. Moreover, these data are usually not presented numerically in the aggregate at the provincial level, but rather in prose that describes the individual disciplinary actions. Furthermore, there is no federal legislation mandating this process. Like the United States, Canada has a Federation of Medical Regulatory Authorities that could potentially act as a repository for information on physician discipline.

Some limitations of our data should be considered. First, we could report only on data that were publicly available. However, it is reasonable to assume the validity of those documents, since they are based upon formal provincial legal proceedings and follow strict procedures. Second, data concerning physicians disciplined in the 3 territories were not publicly available, according to the respective licensing authorities we contacted. However, the territories accounted for fewer than 130 physicians in 200912 and thus would be unlikely to affect our results substantively. Third, we were unable to obtain complete data for all provinces for each year examined in our study. Again, the missing data would likely represent a small proportion of disciplined physicians; moreover, the absence of these data would lead only to an underestimate of the findings. Fourth, we had to exclude physicians whose names were not published, as their demographic characteristics could not be ascertained. Fifth, some of the recorded fine/cost penalty data were not adequately detailed within discipline summaries. In these cases, physicians may have paid hidden expenses and costs that would not be captured by the data collection process. For example, the costs incurred by Quebec physicians were never explicitly outlined in any disciplinary proceedings. For this reason, we elected not to proceed with a more detailed analysis of fines/costs incurred by disciplined physicians. Sixth, since we could not find meaningful national data on percentages of complaints that led to disciplinary action, we have reported only the rates of disciplined physicians, rather than the discipline rate of physicians. Finally, our data pertain only to disciplinary actions and do not inform us about the degree or nature of patient complaints in the provinces.

This study constitutes an important first step in aggregating data on and understanding the extent and nature of disciplinary actions involving physicians in Canada. We have outlined some areas that can be targeted for improvement, and encourage further research into preventing offences requiring disciplinary action. The medical profession must realize that, although disciplined physicians represent a small proportion of the physician population, a single practitioner has tremendous potential to harm patients and the public. There is little doubt that practitioners who violate the boundaries of proper professional conduct diminish the integrity of the medical profession. Regardless, there is a dearth of large-scale programs that address professionalism in medicine with the aim of preventing transgressions from occurring in the first place.22 Expanding and improving this important area of patient safety must be a priority for the medical profession.

Biographies

Asim Alam, MD, is a Senior Resident in the Department of Anesthesiology, Department of Health Policy Management and Evaluation, and in the Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Jason Klemensberg, and

Joshua Griesman, BSc, were summer research students in the Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto.

Chaim M. Bell, MD, PhD, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Health Policy, Management, & Evaluation and CIHR/CPSI Chair in Patient Safety & Continuity of Care, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario Canada.

Appendix

Appendix A.

Provincial medical licensing authorities in Canada

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: Dr. Bell is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Canadian Patient Safety Institute Chair in Patient Safety and Continuity of Care. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributors: Asim Alam helped conceive the project and devise the study methodology, oversaw the data collection, conducted the analyses, and was the principal writer of the manuscript. Jason Klemensberg and Joshua Griesman contributed to the study methodology, performed the data collection, and reviewed the manuscript. Chaim Bell helped conceive the project, devise the study methodology, guide the analysis, and write the manuscript. He serves as the study guarantor. All of the authors approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Monico E, Kulkarni R, Calise A, Calabro J. The criminal prosecution of medical negligence. Internet J Law Healthc Ethics. 2007;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison J, Wickersham P. Physicians disciplined by a state medical board. JAMA. 1998;279(23):1889–1893. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1889. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9634260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardarelli Roberto, Licciardone John C, Ramirez Gilbert. Predicting risk for disciplinary action by a state medical board. Tex Med. 2004;100(1):84–90. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=15146773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardarelli Roberto, Licciardone John C. Factors associated with high-severity disciplinary action by a state medical board: a Texas study of medical license revocation. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(3):153–156. http://www.jaoa.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16585383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clay Steven W, Conatser Robert R. Characteristics of physicians disciplined by the State Medical Board of Ohio. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(2):81–88. http://www.jaoa.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12622353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khaliq Amir A, Dimassi Hani, Huang Chiung-Yu, Narine Lutchmie, Smego Raymond A., Jr Disciplinary action against physicians: who is likely to get disciplined? Am J Med. 2005;118(7):773–777. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.051. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002934305001506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohatsu Neal D, Gould Dawn, Ross Leslie K, Fox Patrick J. Characteristics associated with physician discipline: a case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Mar 22;164(6):653–658. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.653. http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15037494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dehlendorf C E, Wolfe S M. Physicians disciplined for sex-related offenses. JAMA. 1998;279(23):1883–1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doctor loses medical licence for third time for sex with patients. Globe and Mail [Toronto] 2010. Nov 3,

- 10.Larson M, Marcus B, Lurie P, Sidney W. 2006 Report of Doctor Disciplinary Information on State Web Sites 2006 (HRG Publication #1791) Public Citizen. 2006.

- 11.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, distribution and migration of Canadian physicians [2000–2009] Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2000. [accessed 2011 Feb 1]. https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.CAPER (Canadian Post-M.D. Education Registry) Annual census of post-M.D. trainees 2009–2010. Ottawa: Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Medical Directory. Toronto: Scott’s Directories; 1970-2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taragin Mark I, Wilczek Adam P, Karns M Elizabeth, Trout Richard, Carson Jeffrey L. Physician demographics and the risk of medical malpractice. Am J Med. 1992;93(5):537–542. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90582-V. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/000293439290582V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federation of State Medical Boards. Summary of board actions 2009. Euless (TX): Federation of State Medical Boards; 2010. [accessed 2010 Oct 6]. http://www.fsmb.org/pdf/2009-summary-board-actions.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federation of State Medical Boards. Summary of board actions 2006. Euless (TX): Federation of State Medical Boards; 2007. [accessed 2010 Oct 6]. http://www.fsmb.org/pdf/fsmb%202007%20summary%20of%20board%20actions.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federation of State Medical Boards. Summary of Board actions 2004. Euless (TX): Federation of State Medical Boards; 2005. [accessed 2010 Oct 6]. http://www.fsmb.org/pdf/fpdc_summary_boardactions_2004.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant Darren, Alfred Kelly C. Sanctions and recidivism: an evaluation of physician discipline by state medical boards. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2007;32(5):867–885. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2007-033. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=17855720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson Gerard F, Hussey Peter S, Frogner Bianca K, Waters Hugh R. Health spending in the United States and the rest of the industrialized world. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2005;24(4):903–914. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.903. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=16136632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White Gillian E. Setting and maintaining professional role boundaries: an educational strategy. Med Educ. 2004;38(8):903–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01894.x. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White Gillian E. Medical students' learning needs about setting and maintaining social and sexual boundaries: a report. Med Educ. 2003;37(11):1017–1019. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01676.x. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spickard W A, Jr, Swiggart William H, Manley Ginger T, Samenow Charles P, Dodd David T. A continuing medical education approach to improve sexual boundaries of physicians. Bull Menninger Clin. 2008;72(1):38–53. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2008.72.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell J. Unprofessional conduct. CMAJ. 2011;183(5):274. http://www.cmaj.ca/content/183/5/E273.full.pdf. [Google Scholar]