Abstract

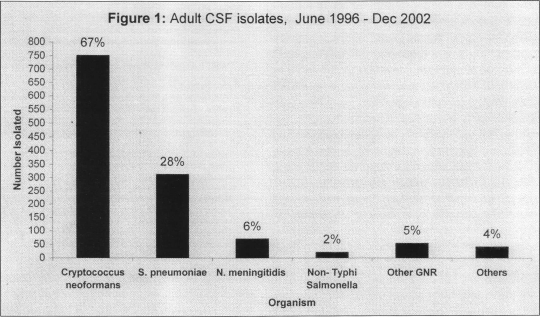

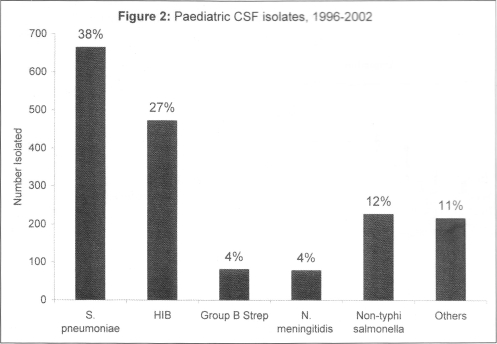

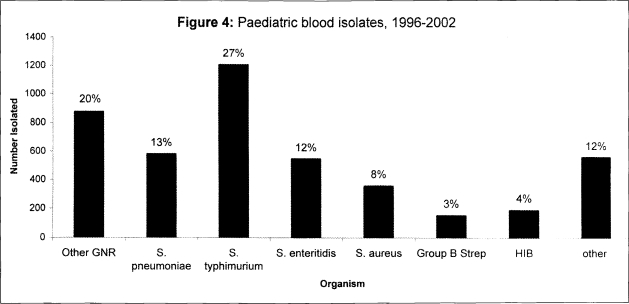

This is a report of blood CSF isolates from the adults medical and paediatric of wards QECH, Blantyre, cultured and identified at the Welcome Trust Research Laboratories during 1996–2002. The commonest causes of adults and children bacteraemia were non-typhoidal Salmonella (35% of all blood isolates for adults and children) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (14% and 13% respectively). Cryptococcus neoformans was the commonest isolates from CSF of adults with meningitis(67%) but was very rare in children. S.pneumoniae was the commonest cause of bacterial meningitis in children and adults (38% and 28% of all CSF isolates respectively). Haemophilus influenzae type b was also a common cause of meningitis in children (27%). Data of in vitro antibiotic sensitivity are also reported. A major concern is the recent marked rise of chloramphenicol resistance among Salmonella enteritidis and Salmonella typhimurium to over 80% resistance.

Introduction

The Wellcome Trust Research Laboratories (WTRL) is situated at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), Blantyre, Malawi. The WTRL has undertaken testing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood culture samples from the adult medical and paediatric wards since 1996. A substantial database of isolates has evolved from this, giving information on the major causative agents of bacteraemia and meningitis in both groups, as well as information on the antibiotic sensitivity of these organisms. This paper reports the major isolates causing invasive disease and their antibiotic resistance patterns over the period from 1996 to 2002.

Methods

CSF and blood culture samples from adult medical and paediatric wards were routinely tested by standard methods at the WTRL. Sampling was done mainly within the research context or less commonly at the discretion of clinicians on the ward. Thus, the total amount of samples received has increased over time in proportion to the increased volume of research and the increased size of the facility and personnel over time. While the CSF data for paediatric meningitis are close to fully representative of all paediatric meningitis since 1996, blood culture data from adults or children underestimate the actual burden of bacteraemia especially in the earlier years.

Blood samples were cultured using a manual culture system from 1996–2000, and using the BacT/Alert 3D automated system, (BioMerieux, Cambridge, UK), from 2000–2002. All isolates were identified using standard diagnostic techniques.1 Antibiotic sensitivity was determined using the NCCLS standard method2 from 1995– June 2001. From July 2001, the standard BSAC method3 was used. In both cases, standard antimicrobial sensitivity discs were used, (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, UK).

Results

CSF isolates

The main cause of adult meningitis in adults admitted to adult medical wards at QECH was Cryptococcus neoformans, accounting for 67% of confirmed cases (Figure 1). Streptococcus pneumoniae was the major cause of bacterial meningitis causing 28% of confirmed cases. From paediatric CSF samples, S.pneumoniae was the most frequent isolates (38%), followed by Haemophilus influenzae type b (27%) (Figure 2). Neisseria meningitides was rarely isolated from adults or children accounting for 6% and 5% respectively. In contrast to adults, Cryptococcus neoformans is a very rare cause of meningitis in children.

Figure 1.

Adult CSF isolates, June 1996–Dec 2002

Figure 2.

Paediatric CSF isolates, 1996–2002

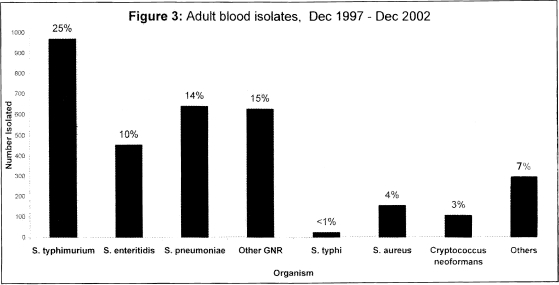

Blood culture isolates

The most common cause of bacteraemia in adults was non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS), of which Salmonella typhimurium accounted for 25% of isolates and Salmonella enteritidis for 10%. S.pneumoniae was the next most common isolates accounting for 14% of isolates. Paediatric blood culture show a similar picture (Figure 4), with the commonest isolates being S.typhimurium (27%), S.enteritidis (12%), and S. pneumoniae (13%).

Figure 4.

Paediatric blood isolates, 1996–2002

Antibiotic sensitivity

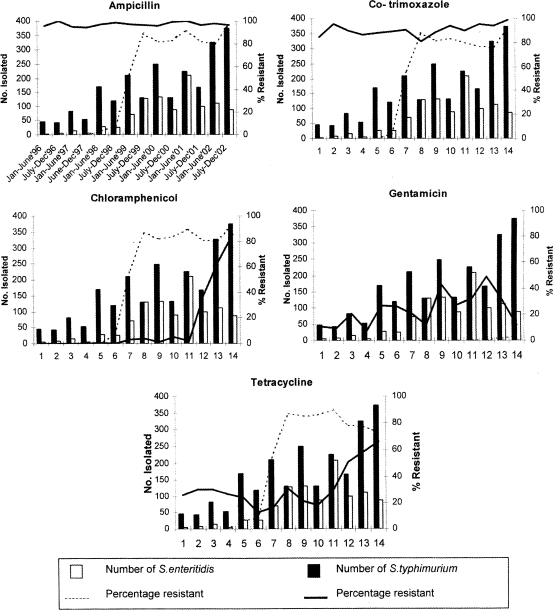

Adult and paediatric isolates show the same pattern of antibiotic sensitivity and so the data presented are combined. The two major NTS isolates show different patterns of antibiotic resistance (Figure 5). S. enteritidis was initially sensitive to all the routinely tested antibiotics, but a dramatic rise in antibiotic resistance was seen in S. enteritidis isolates during 1998/1999, from <10% to >80% resistance for ampicillin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline and cotrimoxazole. It remained sensitive to gentamicin. Most S.typhimurium isolates have been resistant to ampicillin and cotrimoxazole but until 2001, sensitive to chloramphenicol. Since 2001, there has been a dramatic increase in resistance to chloramphenicol so that by the end of 2002, over 80% of S. typhimurium isolates were resistant to chloramphenicol. Some S. typhimurium isolates were also resistant to tetracycline and gentamicin. To date, NTS isolates remain fully sensitive to ciprofloxacin.

Figure 5.

Antibiotic resistance for non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates, 1996–2002.

Twenty percent of S. pneumoniae is resistant to penicillin and 20% resistant to chlorampenicol, though rarely to both antibiotics simultaneously. S. pneumoniae is highly resistant to cotrimoxazole (>80%) but shows little resistance to erythromycin (<1%). H. influenzae type b isolates show high levels of resistance to ampicillin (61%) and contrimoxazole (66%). Resistance to chloramphenicol remain relatively low (27%) until 2000 but has since risen to 80%. H. influenzae type b (Hib) isolates remain sensitive to gentamicin and cefriaxone. Invasive infections due to N. meningitides are relatively rare at QECH - there have been 196 isolates from both adult and paediatric patients over 6 years. N. meningitides isolates are sensitive to penicillin, chloramphenicol and erythromycin. They show some resistance to gentamicin (22%) and high levels of resistance to cotrimoxazole (86%).

Discussion

These surveillance data from QECH over six years provide important information of the prevalence of common invasive bacterial pathogens and of antibiotic resistance in urban Blantyre. As clinical management decisions such as choice of antibiotic need to be made before the results of bacterial culture are available, these data are useful in developing clinical guidelines for first-line therapy at the hospital. However, the data may not be representative of the entire country - for example, the urban setting usually has higher levels of antibiotic resistance than rural setting because of more frequent use and increased availability of antibiotics. The relative prevalence of different bacteria may also vary with season. This is particularly the case with NTS bacteraemia, more frequent during the rainy season in adults and children.4,5 This seasonal pattern with NTS is also evident from our data (see Figure 5). A hospital - based prevalence survey of bloodstream infections in adults showed the commonest bacteria to be S. pneumoniae at Lilongwe Central Hospital during the dry season 6, while similar surveys at LCH and QECH during the wet season found NTS to be the commonest cause of bacteraemia in adults.4,7 Previous reports from QECH show that the majority of bacteraemia in adults is HIV - related. 8,9

Our data do not indicate the importance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a common cause of bloodstream infection in adults at QECH (17%) and LCH (19%).6,7 This is because blood culture for M. tuberculosis is not routine. Studies of children have found mycobacteraemia to be rare at LCH10 and at QECH (unpublished data, EM Molyneux). The prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans as a cause of bloodstream infection in adults was also similar in the two major hospitals6,7 and compares to that found in our surveillance data (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adult blood isolates Dec 1997 – Dec 2002

Over the period of surveillance for this report, C. neoformans was the commonest CSF isolates in adults but was very rare in children.

The commonest bacterial cause of meningitis in adults and children is S.pneumoniae. This is consistent with earlier report which includes some of the reported data in this study. 8,11 H. influenzae was the second common cause in children but rarely causes meningitis in adults. It will be interesting to examine the impact of the introduction of the conjugate Hib vaccine as routine immunisation for Malawian infants from early 2002 on subsequens surveillance data at QECH. Data from south African children suggest that there will be a significant reduction of invasive Hib disease.12 If Hib conjugate vaccine is effective in Malawi, NTS is likely to become the second commonest cause of childhood bacterial meningitis.11 N. meningitides is not a common cause of meningitis at QECH.

NTS is the commonest cause of bacteraemia in children admitted to QECH.13 This is consistent with data from elsewhere in tropical Africa.14–16 NTS bacteraemia is more common during the rainy season and there is a strong association of NTS bacteraemia with malaria and anaemia.16 The association of HIV with NTS bacteraemia is very marked in adults9,17 but in children the impact of HIV on NTS bacteraemia is less clear.16 S. pneumoniae was the second commonest cause of childhood bacteraemia in this report. In USA and South Africa, the incidence of pneumococal bacteraemia is increased twenty to forty-fold in HIV-infected children.18,19 The HIV status of most children reported in this study is not known. The efficacy of the recently developed pneumococcal conjugate vaccine has been studied in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected South African children20 and results will soon be published.

Increasing resistance of common bacteria to the readily available antibiotics is a major concern. The first-line treatment for adults and children at QECH with suspected bacteraemia, septicaemia, or meningitis has been chloramphenicol plus penicillin. In vitro resistance for S. pneumoniae to penicillin and chloramphenicol has remained relatively steady over time (around 20%) and isolates are usually resistant to one or other of the antibiotics but very rarely to both. Penicillin is ineffective against NTS but until recently, almost all NTS isolates were sensitive to chloramphenicol. The recent rapid rise in resistance of S. enteritidis and S. typhimurium to chloramphenicol in 1999 and 2001 respectively (Figure 5) has resulted in a clinical management dilemma. Gentamicin is being used increasingly in addition to chloramphenicol for proven or suspected invasive NTS disease but intracellular penetration is poor. Thus, it may not be as effective an antibiotic against NTS even when there is in vitro sensitivity. Ciprofloxacin is an effective alternative but only oral preparation is available and this is problematic for administration and possibly absorption in very ill patients.

References

- 1.Barrow GI, RKA F, editors. Cowan and Steel's Manual for the identification of medical bacreria. Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villanova PA National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, author. Perfomance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.BSAC Working Party, author. BSAC disc diffusion method for antimicrobial susceptibility Testing. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell M, Archibald L K, Nwanyanwu O, Dobbie H, Tokars J, Kazembe P N, et al. Seasonal variation in the etiology of bloodstream infections in a ferbrile in patient population in a developing country. Int J Infect Dis. 2001;5:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(01)90027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham SM, Walsh AL, Molyneux EM. The clinical presentation of non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteramia in Malawian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000:320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Archibald LK, McDonald LC, Nwanyanuwu O, Kazembe P, et al. A hospital-based prevelance survey of bloodstream infections in febrile patients in Malawi:implications for diagnosis and therapy. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1414–1420. doi: 10.1086/315367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis DK, Peters RPH, Schijffelen MJ, Joaki GRF, et al. Clinical indicators of mycobacteraemia in adults admitted to hospital in Blantyre, Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:1067–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon SB, Chaponda M, Walsh AL, Whitty CJ, Gordon MA, Machili CE, et al. Pneumococcal disease in HIV-infected Malawian adults: acute mortality and long-tem survival. AIDS. 2002;16:1409–1417. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207050-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon MA, Walsh AL, Chaponda M, Soko D, Mbvwinji M, Molyneux ME, Gordon SB. Bacteraemia and mortality among adult medical admission in Malawi—predominance of non-typhi salmonella and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect. 2001;42:44–49. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archibald LK, Nwanyanwu O, Kazembe PN, Mwansambo C, et al. Detection of bloodstream pathogens in a bacilli Calmette-Guerin (BCG)-vaccinated pediatric population in Malawi: a pilot study. Clinical Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:234–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molyneux EM, Walsh AL, Forsyth H, Tembo M, Mwenechanya J, Kayira K, et al. Dexamethasone treatment in childhood bacterial meningitis in Malawi: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madhi SA, Petersen K, Khoosal M, et al. Reduced effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in children with a high prevalence of human immunodefeciency virus type 1 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:315–321. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh AL, Phiri AJ, Graham SM, Molyneux EM. Bacteremia in febrile Malawian children: clinical and microbiological features. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:312–318. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nesbitt A, Mirza NB. Salmonella septicaemia in Kenyan Children. J Trop Pediatr. 1989;35:35–39. doi: 10.1093/tropej/35.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green SDR, Cheesbrough JS. Salmonella bacteraemia among young children at a rural hospital in western Zaire. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1993;13:45–54. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1993.11747624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham SM, Molynoenux EM, Walsh AL, Cheesbrough JS, Molyneux ME, Hart CA. Non-typhoidal Salmonella infections of children in tropical Africa. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1189–l196. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200012000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon MA, Banda HT, Gondwe M, et al. Non typhoidal salmonella bacteraemia among HIV-infected Malawian adults: high mortality and frequent recrudescence. AIDS. 2002;16:1633–1641. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200208160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farley JJ, King JC, Nair P, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among infected and uninfected children of mothers with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Pediatr. 1994;124:853–858. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madhi SA, Petersen K, Madhi A, et al. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on the disease spectrum of Streptococcus pneumoniae in South African children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1141–1147. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200012000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medhi SA, Cumin E, Klugman KP. Defining the potential impact of conjugate bacterial polysaccharide-protein vaccines in reducing the burden of pneumonia in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:393–399. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200205000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]