Summary

Whether endovascular surgery is able to reduce the mass effects of unruptured aneurysms is still controversial, although some reports have suggested efficacy in cases of internal carotidartery aneurysms with cranial nerve palsy. Here we assessed outcome in a series of cases.

Between April 1992 and April 2005, 18 patients with unruptured internal carotid artery aneurysms presenting with cranial nerve palsy were treated by endovascular surgery. The patients were two males and 16 females aged from 19 to 84 (mean 59.6 years). Aneurysms were located in the cavernous portion in 14, at the origin of the ophthalmic artery in one and at the origin of P-com in three. The aneurysms were all embolized using Guglielmi detachable coils, Interlocking detachable coils, Cook's detachable coils or Trufill DSC and detachable Balloons were applied to occlude the proximal parent artery.We analyzed the efficacy of endovascular surgery for such aneurysms retrospectively.

The mean aneurysm size was 21.4 mm and the mean follow-up period was 57.7 months. Palsy of IInd cranial nerve was evident in three patients, of the IIIrd in eight, of the Vth and Vth in one each, and of the VIth in nine. Post embolization occlusion was complete in nine patients and neck remnant in the other seven.

Regarding complications of endovascular surgery, one case (5.6%) showed TIA after embolization. Overall 11 (46%) cranial nerve symptoms showed complete resolution, eight (33%) showed some improvement, and five (21%) were unchanged. In three cases (12.5%), the symptoms worsened after treatment. The shorter the duration of symptoms was a factor predisposing to resolution of symptoms. In complete resolution cases, the timing of treatment after symptoms appeared and the time of complete resolution were in proportion

These results showed that there is no difference in reduction of mass effects between surgical clipping and endovascular surgery for unruptured internal carotid artery aneurysms.With endovascular surgery, the rapidity of treatment after symptoms is the most important factor for successful results.

Key words: internal carotid artery aneurysm, cranial nerve palsy, endovascular surgery

Introduction

The standard treatment of patients with aneurysms causing cranial nerve palsy has been direct surgery 1-3. Since this is difficult to perform for cavernous portion internal carotid artery aneurysms, endovascular surgery may be needed for such cases.

However, endovascular treatment of unruptured aneurysms causing mass effects on cranial nerves is still controversial4-6. The present study was conducted to evaluate its efficacy for a series of internal carotid artery aneurysms with cranial nerve palsy.

Material and Methods

Between April 1992 and April 2005, 18 patients with unruptured internal carotid artery aneurysms with cranial nerve palsy were treated by endovascular surgery in our institution. All were retrospectively examined for their clinical symptoms over time for analysis of efficacy. The patients were two males and 16 females aged from 19 to 84 (mean 60.6 years). The aneurysms were located in the cavernous portion in 14, at the origin of ophthalmic artery in one and at the origin of P-com in three. Embolization was performed under focal anesthesia after systemic heparinisation with a bolus of 2000 IU, followed by continuous injection of 200 IU/min and maintenance of an activated coagulation time (ACT) more than twice the control value. A microcatheter (Excelsior, Excel 14 or SL-10; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts) was carefully inserted into the aneurysm with the guidewire and embolization was achieved using Guglielmi detachable coils (GDC; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts), interlocking detachable coils (IDC; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts), Cook's detachable coils (CDC; Cook Inc.), Trufill DCS (Johnson & Johnson) or detachable balloon occluded proximal parent artery. Post embolization, anti-platelet therapy using aspirin was started, and continued for six months. The following cranial nerve symptoms and signs were evaluated and all patients were followed by MRA and thin slice MRI.

Results

Our patient details are summarized in table 1. The mean aneurysm size was 21.4 mm (range 5 to 40 mm). Three patients had palsy of the II, eight of the III, one each of the IV and V, and nine of the VI cranial nerve. The timing of treatment by endovascular surgery was a mean of 176.9 days after the initial symptoms appeared. The mean follow-up period was 57.7 months. Post-embolization occlusion was complete in nine patients and seven had neck remnants. The final occlusion results were complete in 14 patients and neck remnant in the remaining four.

Table 1.

Summary of our 18 aneurysms cases with CNS palsy treated by endovascular surgery.

| Case No |

Age/ Sex |

Location of An |

CNS | Size (mm) |

Treatment | Occlusion rate at post embolization |

Result | Complication | Timing of treatment (day) |

Timing of CNS deficits improved (day) |

Period of CNS deficits complete resolusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 59/F | Lt. IC | III VI |

40 | IDC | complete | complete unchange |

none none |

181 | 2 none |

13 months none |

| 2 | 74/F | Lt. IC | III VI V |

35 | IDC | neck rem | complete improvement complete |

none none none |

91 | 47 47 47 |

68 days none 68 days |

| 3 | 69/F | Rt. IC cavernous | III | 25 | GVB | complete | complete | temporary worsening | 244 | 3 | 14 days |

| 4 | 54/F | Lt. IC cavernous | VI | 21 | GVB | complete | complete | none | 242 | 50 | 65 days |

| 5 | 20/F | Rt. IC cavernous | VI | 27 | IDC | neck rem | complete | none | 88 | 60 | 375 days |

| 6 | 38/F | Lt. IC | VI | 20 | GDC | complete | improvement | new cranial nerve deficit (Vth) |

51 | 205 | none |

| 7 | 61/F | Lt. IC-Opth. | II | 30 | GDC | neck rem | complete | none | 64 | 26 | 26 days |

| 8 | 19/F | Lt. IC cavernous | II | 10 | GDC | complete | complete | none | 527 | 116 | 375 days |

| 9 | 74/F | Rt. ICPC | III | 5 | GDC | complete | improvement | temporary worsening | 2 | 83 | none |

| 10 | 68/F | Rt. IC cavernous | VI | 18 | IDC | neck rem | improvement | none | 116 | 23 | none |

| 11 | 70/F | Lt. IC cavernous | III IV VI |

20 | GDC | neck rem | complete complete complete |

none none none |

21 | 1 1 1 |

31 days 31 days 66 days |

| 12 | 71/M | Lt. IC | VI | 15 | GDC | neck rem | unchange | none | 720 | none | none |

| 13 | 78/M | Lt. ICPC | III | 7 | GDC | complete | improvement | none | 99 | 51 | none |

| 14 | 84/F | Rt. ICPC | III | 8 | GDC | complete | improvement | none | 14 | 37 | none |

| 15 | 57/F | Lt. IC cavernous | VI | 30 | GVB | complete | improvement | none | 226 | 16 | none |

| 16 | 58/F | Bil. IC cavernous | II III |

30 | GVB | complete | unchange unchange |

none snone |

400 400 |

none none |

none none |

| 17 | 58/F | Lt. IC cavernous | II | 20 | GDC+CDC+DCS | complete | unchange | temporary worsening | 930 | none | none |

| 18 | 60/F | Lt. IC cavernous | III | 24 | GDC+CDC+DCS | neck rem | improvement | none | 370 | 21 | none |

| GDC; Guglielmi detachable coil, IDC; Interlocking detachable coil, GVB; Gold valve baloon, CDC; Cook's detachable coil, DCS; Trufill DCS | |||||||||||

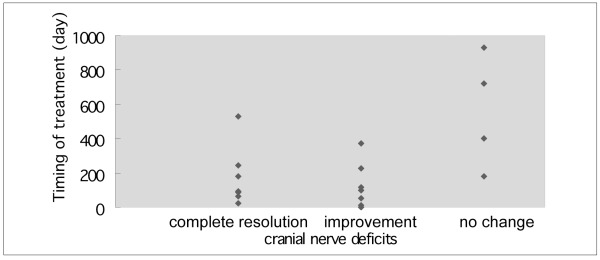

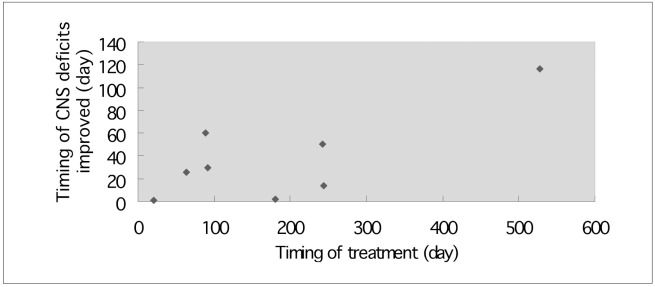

Overall, 11 (46%) cranial nerve symptoms showed complete resolution, eight (33%) symptoms showed some improvement, and five (21%) symptoms were unchanged. However, in three cases (12.5%), symptoms worsened temporarily after treatment. In complete resolution cases, the aneurysm mean size was 19.6 mm (range 10 mm to 40 mm) and the mean follow-up period was 71.1 months (table 2). The timing of treatment in these cases was 140.2 days (mean), and the time to complete resolution was 137.6 days (mean) (table 2). In partial improvement cases, aneurysm mean size was 18.4 mm (range 5 mm to 35 mm) and the mean follow-up period was 38.2 months (table 2). The timing to treatment in these cases was 125.5 days (mean) (table 2). In unchanged cases, aneurysm mean size was 27 mm (range 15 mm to 40 mm) and the mean follow-up period was 43.4 months (table 2). The timing to treatment was 526.2 days (mean) (table 2). The relationship of the timing to treatment and change in symptoms are shown in figure 1. The shorter the period for treatment is the most important factor for better resolution. In those where this was complete, the timing to treatment after symptoms appeared and the time for resolution were in proportion (figure 2)

Table 2.

The results of endovascular surgery for the aneurysms with CNS palsy.

| Case No. of CN |

Size of An (mean · mm) |

Timing of treatment (mean · day) |

Timing of started improvement of CNS (mean · day) |

Period of complete resolution of CNS (mean · day) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| complete resolusion | 11 | 19.6 | 140.2 | 32.2 | 137.6 |

| some improvement | 8 | 18.4 | 125.5 | 60.4 | (—) |

| unchanged / worsened | 5 | 27 | 526.2 | (—) | (—) |

Figure 1.

The relationship of the timing to treatment and change in symptoms. The shorter the period before treatment is the most important factor for better resolution.

Figure 2.

The relationship of the timing to treatment after symptoms appeared and the timing for resolution in complete resolution cases. The period of complete resolution of cranial nerve deficits is in proportion to the timing to treatment after symptoms appeared.

The complete resolution rates for CN symptoms were 50% for optic nerves, 44% for III, 100% for IV, 100% for V and 33% for VI cranial nerves (table 3). In intracranial aneurysm cases, the mean size was 12.5 mm. These cases showed complete resolution of CN symptoms in 25%, and some improvement in 75% (table 4). In extradural aneurysm cases, these mean size was 23.9 mm, complete resolution of CN symptoms was found in 50%, some improvement in 25% and no change in 25% (table 4). Regarding complications of endovascular surgery in our cases, one (5.6%) showed TIA after embolization.

Table 3.

Summury of the clinical data and the results of the treatment in our cases.

| Cases | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| male | 2 |

| female | 16 |

| Location | |

| IC cavernous | 14 |

| IC-Ophthalmic | 1 |

| ICPC | 3 |

| An size (mean; mm) | 21.4 |

| Symptoms of CNS | |

| II | 4 |

| III | 9 |

| IV | 1 |

| V | 1 |

| VI | 9 |

| Timing of EVS (mean;day) | 229.5 |

| Results of CNS | |

| complete resolution | 46% (11/24) |

| improvement | 33% (8/24) |

| no change+B50 | 21% (5/24) |

| Resolution rate(cranial nerve) | |

| II | 50% (2/4) |

| III | 44% (4/9) |

| IV | 100% (1/1) |

| V | 100% (1/1) |

| VI | 33% (3/9) |

| Temporary worsening | 12.5% (3/24) |

| The date of improvement (mean;day) | 44.1 |

| The date of complete resolution (mean; day) | 137.6 |

| An; aneurysm, EVS; endovascular surgery | |

Table 4.

The comparision of clinical data and resuls for treatment of intradural or extradural aneurysm.

| cases No | size of An (mean;mm) |

follow-up (month) (days) |

timing of treatment (mean)(days) |

cranial nerve deficits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| complete resolution |

some improvement |

unchanged | |||||

| intradural | 4 | 12.5 | 23 | 44.75 | 25% | 75% | 0% |

| extradural | 14 | 23.9 | 65.15 | 250.8 | 50% | 25% | 25% |

Discussion

Generally surgical clipping for intracranial aneurysms with mass effect symptoms has advantages with regard to reduction of the mass effect for cranial nerves compared with endovascular surgery. In a published report of clipping surgery for unruptured aneurysms, Drake et Al10 reported 37% of 27 patients showed complete resolution or improvement. Peiris et Al 13 reported a 30% success rate in ten cases, Ferguson et Al11 45.8% in 24 cases, Herose et Al14 55.6% in 18 cases, Symon et Al15 71% in 14 cases, Whittle et Al16 0% in six cases and Rice et Al 17 57.1% in seven cases. For ruptured aneurysms, Giombini et Al9 reported 62% of patients treated within 14 days of initial symptom appearance to show complete resolution as compared to 25% of patients treated after 14 days (table 5).

Table 5.

The results of treatment for the aneurysms with CNS palsy in published reports.

| case No. | cranial nerve deficits | timing of treatments (mean;day) |

improvement Noted at (mean; day) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| complete resolution (%) |

improvement (%) |

no change or worsening (%) |

||||

| Endovascular surgery | ||||||

| Unruptured An | ||||||

| Halbach et Al (1994) | 26 | 50 | 42,3 | 7,7 | 180 | ? |

| Guglielmi et Al (1998) | 19 | 32% | 42% | 26% | 620.5 | ? |

| Kim et Al (2003) | 7 | 29% | 43% | 29% | ? | 82.5 days |

| Our cases (2005) | 18 | 50% | 29% | 21% | 229.5 | 36 days |

| Direct surgery | ||||||

| Unruptured An | ||||||

| Drake (1979) | 27 | 37* | 63 | ? | ? | |

| Peiris et Al (1980) | 10 | 30* | 70 | ? | ? | |

| Ferguson et Al (1981) | 24 | 45.8* | 54.2 | ? | ? | |

| Heros et Al (1983) | 18 | 55.6* | 44.4 | ? | within 180-360 | |

| Symon et Al (1984) | 14 | 71.* | 28.6 | ? | ? | |

| Whittle et Al (1984) | 6 | 0* | 100 | 90 | (-) | |

| Rice et Al (1990) | 7 | 57.1* | 42.9 | ? | ? | |

| Ruptured An | ||||||

| Giombini et Al (1991) | 13 | 62 | 38 | 0 | before 14 | ? |

| Giombini et Al (1991) | 36 | 25 | 55 | 20 | after 14 | ? |

| *;included complete resolution and improvement cases, An;aneurysm | ||||||

However, cavernous portion internal carotid artery aneurysms are very difficult to treat by clipping and therefore recently interest has therefore focused on reports that endovascular surgery for aneurysm with mass effect is effective because of reduction of aneurysm size after endosacular embolization 4,5. There is no standard management by endovascular surgery for intracranial aneurysms with mass effect symptoms, but Halbach et al.4 reported 50% of patients to show complete resolution of CN symptoms after endovascular surgery.

Malish et Al 3 reported completed resolution in 32% of cases, Kim et Al6 in 29% and Kazekawa et Al8 in 42%. These reports and our present results indicate that there is no difference in rates of reduction of the mass effect between surgical clipping and endovascular surgery. Furthermore, endovascular treatment for aneurysms with mass effects by endosaccular embolization has also been described 1,2,7

What factors influence outcome of endovascular surgery? Halbach et Al4 emphasized detrimental effects of a long duration of symptoms such as calcification of aneurysm walls. Malish et Al3, in contrast, reported small size of aneurysm and short duration to be positive factors. Kazekawa et Al 8 found cases treated within 12 months of initial symptom to have good outcomes. In our patients, the times to treatment after symptoms appeared was 140.2 days in complete resolution cases, 125.5 days in partial improvement cases and 526.2 days in unchanged cases. The aneurysm mean sizes were 19.6,18.4 and 27 mm, respectively.

Is the location of an aneurysm related to results of endovascular surgery? Kim et Al 6 reported showed better improvement or resolution with intradural as opposed to extradural aneurysms. In our cases, all intracranial cases showed improvement or resolution, whereas resolution was complete in 50% of extradural aneurysm cases but no change resulted in 25%.

One reason for poor results is that extradural aneurysms exhibit symptoms very slowly, so the duration of pressure on cranial nerves is long. Endovascular treatment for ICPC aneurysms allowed complete resolution in 80% of series described by Miyachi et Al in a text-book. These aneurysms cause CN symptoms from early stages, and therefore tend to be treated immediately. In contrast, results for optic nerve disorders with paraclinoid aneurysms are less positive. Thornton et Al12 reported six cases, in only two of which was resolution complete and 38% patients became blind after treatment. Upper and upper-inside type ophthalmic and carotid anterior wall type aneurysms have high optic nerve disorder rates, and symptoms frequently worsen after treatment. Malish et Al3 found many patients with ophthalmic aneurysms to need re-treatment, and discussed three reasons for poor results. The first is that optic symptoms appear very slowly. The second is that the pressure point is near the optic canal so the space of nerve decompression is very narrow. The last is that ischemic complications for optic nerves may be caused by endovascular treatment. In our series, three cases had temporary worsening of symptoms after embolization. From basic research, the aneurysms may enlargement temporarily after endosaccular embolization. However, in our cases the volumes of aneurysms were reduced after one month.

Conclusions

The present results indicated that there may be no differences in rates for reduction of mass effects between surgical clipping and endovascular surgery for cases of unruptured internal carotid artery aneurysms presenting with cranial nerve symptoms. With endovascular surgery, rapidity of treatment after symptoms appear is the most important factor for successful results. In future, covered stent therapy might be substituted for endovascular coil embolization for these aneurysms.

References

- 1.Inamasu J, Nakamura Y, et al. Early resolution of third nerve palsy following endovascular treatment of a posterior communicating artery aneurysm. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2002;22:12–14. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birchall D, Khahgure MS, McAuliffe W. Resolution of third nerve paresis after endovascular management of aneurysms of the posterior communicating artery. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:411–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malisch TW, Guglielmi G, et al. Unruptured aneurysms presenting with mass effect symptoms: response to endovascular treatment with Guglielmi detachable coils. Part I. Symptoms of cranial nerve dysfunction. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:956–961. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, et al. The efficacy of endosaccular aneurysm occlusion in alleviating neurological deficits produced by mass effect. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:659–666. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.4.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuura M, Terada T, et al. Magnetic resonance signal intensity and volume changes after endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms causing mass effect. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:184–188. doi: 10.1007/s002340050565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DJ, Kim DI, et al. Unruptured aneurysms with cranial neurve symptoms: Efficacy of endosaccular Guglielmi detachable coil treatment. Korean J Radiol. 2003;4(3):141–145. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2003.4.3.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe A, Imamura K, Ishii R. Endovascular aneurysm occlusion with Guglielmi detachable coils for obstructive hydrocephalus caused by a large basilar tip aneurysm. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:675–678. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.4.0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazekawa K, Tsutumi M, et al. Internal carotid aneurysms presenting with mass effect symptoms of cranial nerve dysfunction: Efficacy and limitations of endosaccular embolization with GDC. Radiation Medicine. 2003;21:80–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giombini S, Ferraresi S, Pluchiono F. Reversal of ocolomotor disorders after intracranial aneurysm surgery. Acta Neurochir. 1991;112:19–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01402449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drake CG. Giant intracranial aneurysm: experience with surgical treatment in 174 patients. Clin Neurosurg. 1979;26:12–95. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/26.cn_suppl_1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson GG, Drake CG. Carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms: visual abnormalities in 32 patients and the results of treatment. Surg Neurol. 1981;16:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(81)80049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thornton J. Endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 2000;54:288–299. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peiris JB, Russell R. Giant aneurysms of the carotid system presenting as visual field defect. J Neurology. 1980;43:1053–1064. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.43.12.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heros RC, Nelson PB, et al. Large and giant paraclinoid aneurysms: surgical techniques, complications, and results. Neurosurgery. 1983;12:153–163. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Symon L, Vajda J. Surgical experiences with giant intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:1009–1028. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.61.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittle IR, Dorsch NW, Besser M. Giant intracranial aneurysms: diagnosis, management, and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1984;21:218–230. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(84)90191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice BJ, Peerless SJ, Drake CD. Surgical treatment of unruptured aneurysms of the posterior circulation. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:165–173. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.2.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]