SUMMARY

Understanding how RNA binding proteins control the splicing code is fundamental to human biology and disease. Here we present a comprehensive study to elucidate how heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoparticle (hnRNP) proteins, among the most abundant RNA binding proteins, coordinate to regulate alternative pre-mRNA splicing (AS) in human cells. Using splicing-sensitive microarrays, cross-linking and immunoprecipitation coupled with high-throughput sequencing, and cDNA sequencing, we find that more than half of all AS events are regulated by multiple hnRNP proteins, and that some combinations of hnRNP proteins exhibit significant synergy, whereas others act antagonistically. Our analyses reveal position-dependent RNA splicing maps, in vivo consensus binding sites, a surprising level of cross- and auto-regulation among hnRNP proteins, and the coordinated regulation by hnRNP proteins of dozens of other RNA binding proteins and genes associated with cancer. Our findings define an unprecedented degree of complexity and compensatory relationships among hnRNP proteins and their splicing targets that likely confer robustness to cells.

INTRODUCTION

Nascent transcripts produced by RNA polymerase II in eukaryotic cells are subject to extensive processing prior to the generation of a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). In human cells, a sizable fraction of these precursor mRNAs (pre-mRNAs) is associated with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoparticle (hnRNP) proteins, forming large hnRNP-RNA complexes (Dreyfuss et al., 1993). These complexes can contain any combination of at least 20 major hnRNP proteins named hnRNP A1 through hnRNP U. Rivaling histones in their abundance, hnRNP proteins assemble on pre-mRNAs in a combinatorial arrangement dictated by their relative abundances and recognition of specific RNA sequences (Dreyfuss et al., 2002).

HnRNP proteins are multifunctional, participating in all crucial aspects of RNA processing, including pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA export, localization, translation and stability (Han et al., 2010). Of particular interest is the increasingly evident impact of hnRNP proteins on the regulation of alternative splicing (AS), where splice sites within a pre-mRNA are preferentially selected or repressed to produce different mRNA isoforms. The process of AS contributes drastically to proteome diversity, with recent estimates that greater than 90% of human genes can undergo AS (Wang et al., 2008). The proper control of AS is essential for cellular development and homeostasis. Consequently, misregulation of specific AS events has been shown to result in several diseases, such as spinal muscular atrophy (Kashima and Manley, 2003), and global misregulation of AS has been shown to occur in multiple forms of cancer (Gardina et al., 2006; Lapuk et al., 2010; Misquitta-Ali et al., 2011). In addition, hnRNP proteins are misregulated in particular cancer cell types and have been shown to directly affect AS events that promote cancer (David et al., 2010; Golan-Gerstl et al., 2011).

Most hnRNP proteins have been implicated in AS, however, a majority of these reports were based on single-gene studies and in vitro assays. The first systematic AS analysis for the hnRNP protein family used siRNAs against 14 of the major hnRNP proteins in three different human cell lines, followed with an RT-PCR screen restricted to 56 AS events (Venables et al., 2008). Recent advances in genome-wide technologies have allowed for more global assessments of AS. Progress has been made using splicing-sensitive microarrays or RNA sequencing to identify genome-wide AS events (Katz et al., 2010) and using biochemical approaches such as iCLIP (Konig et al., 2010) and CLIP-seq (Katz et al., 2010) to identify binding sites for hnRNP C and for hnRNP H1, respectively. In Drosophila, genome-wide AS changes were identified for the orthologous hnRNP A/B family and, combined with immunoprecipitation strategies, revealed that the 4 hnRNP family members tested bound and regulated a set of overlapping, but distinct target RNAs (Blanchette et al., 2009). Nevertheless, it is unknown whether this mode of co-regulation is conserved in humans.

In this study we used genome-wide approaches to identify hnRNP-regulated AS events in human cells and examined the impact of their regulation. Using siRNAs to deplete the protein levels of 6 major hnRNP proteins, A1, A2/B1, F, H1, M, and U, and splicing-sensitive human exon-junction microarrays (Affymetrix HJAY) we have identified thousands of hnRNP-dependent exons. A battery of analyses demonstrated that the majority of hnRNP-dependent AS events are regulated by multiple hnRNP proteins and depletion of individual members of a set of hnRNP proteins acts to cause similar sets of AS changes. Using antibodies specific for hnRNP proteins A1, A2/B1, F, M and U, we performed cross-linking and immunoprecipitation followed by high throughput sequencing (CLIP-seq or HITS-CLIP) to identify direct binding sites that contribute to the regulation of AS events. Combination of our data revealed six new interrelated RNA splicing maps for the major hnRNP proteins. Finally, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was used to show that hnRNP proteins regulate a significant subset of RNA binding proteins (RBPs) and cancer-associated genes, implicating hnRNP proteins in the regulation of other aspects of RNA processing and general pathways in cancer.

RESULTS

Identification of thousands of hnRNP-dependent human AS events

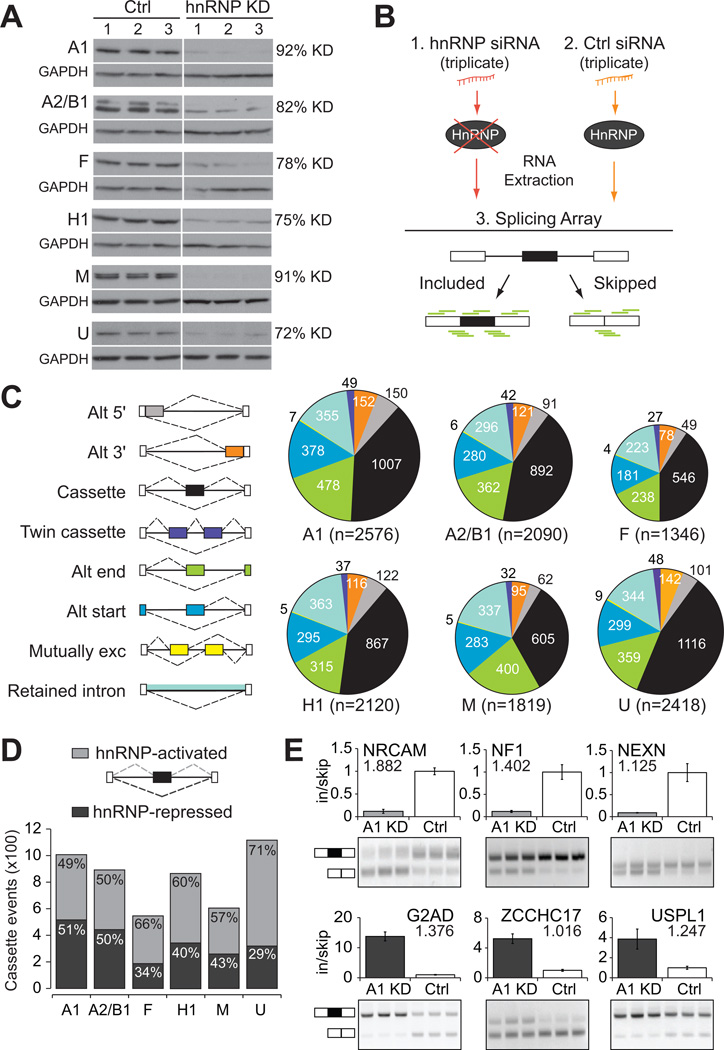

To identify genome-wide alternative splicing (AS) events regulated by hnRNP proteins, we reduced the protein levels of hnRNP proteins A1, A2/B1, F, H1, M and U to 8–28% of their endogenous levels in human 293T cells (Figure 1A). Splicing-sensitive microarrays were used to discover AS events that change significantly upon depletion of specific hnRNP proteins relative to a non-targeting control siRNA (Figure 1B). Hierarchical clustering of normalized intensities for all microarrays showed that the triplicate experiments for specific hnRNP depletions group together appropriately (Figure S1A). Using a published analysis procedure (Sugnet et al., 2006), we identified 6,555 altered AS events upon hnRNP depletion, representing 4,638 human genes. This widespread regulation of AS events is consistent with the reported splicing regulatory roles of hnRNP proteins A1, A2/B1, F, H1 and M (Figure 1C). Depletion of the well-studied splicing regulator hnRNP A1 affects the largest number of AS events (2,576). Surprisingly, depletion of hnRNP U, which previously showed little evidence for splicing regulation (Martinez-Contreras et al., 2007), affects almost as many AS events (2,418) as hnRNP A1. As hnRNP proteins affected different types of AS in similar ratios (Figure 1C), we focused our analysis on the most represented category, cassette exons, where a single exon was either included or skipped from a mature mRNA transcript. In total, the inclusion of 2,586 cassette exons were affected by hnRNP protein depletion, ranging from 546 exons for hnRNP F to 1,116 exons for hnRNP U. Thus far, this dataset contains thousands more human AS events whose splicing regulation is dependent on hnRNP proteins than previously published hnRNP studies (Katz et al., 2010; Konig et al., 2010; Llorian et al., 2010; Venables et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Thousands of hnRNP-dependent alternative splicing events identified in human cells.

(A) Western analysis demonstrating successful depletion of hnRNP proteins A1, A2/B1, F, H1, M, and U in human 293T cells in triplicate experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control. The extent of protein depletion was quantified by densitometric analysis. (B) Experimental strategy for identification of alternative splicing (AS) events. Total RNA was extracted from human 293T cells treated with (1) hnRNP-targeting siRNA(s), or (2) a control non-targeting siRNA, and (3) was subjected to splicing-sensitive microarrays (probes depicted in green). (C) Pie charts of differentially regulated AS events as detected by splicing arrays. Colors represent the types of AS events that were detected and the size of each pie chart reflects the number of events detected. (D) Cassette exons differentially regulated upon depletion of individual hnRNP proteins, relative to control. Bars are divided to display the proportion of events that are less included upon depletion (hnRNP-activated, light gray), or more included upon depletion (hnRNP-repressed, dark gray). (E) RT-PCR validation of hnRNP A1-regulated cassette exons (P < 0.01, t-test). Light gray indicates activation of exon inclusion and dark gray indicated repression of exon inclusion. Absolute separation score predicted by the splicing array analysis is listed below the affected gene name. Bar plots represent densitometric analysis of bands and error bars are standard deviations within triplicate experiments (See also Figure S1).

HnRNP proteins activate and repress cassette exons

To provide insight into whether hnRNP proteins activate or repress exon recognition, we determined what fraction of exons showed increased inclusion (or exclusion) when a particular hnRNP was depleted, a response expected for exons repressed (or activated) by the regulator. By this criterion, hnRNP proteins A1 and A2/B1 repress the largest fractions of cassette exons (Figure 1D). This is consistent with splicing repression by hnRNP A1 and A2/B1 (Martinez-Contreras et al., 2007); however, their presence also appears necessary for exon inclusion. In fact, hnRNP proteins F, H1, M, and U appear to activate exon inclusion for a majority of the cassette exons they affect (Figure 1D). The same trend is also observed for other types of AS events, where after depletion, more than half of the events dependent on hnRNP F, H1, M and U show increased skipping, and more than half of the events dependent on hnRNP A1 and A2/B1 show increased inclusion. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR experiments successfully validated 89% of the 84 cassette exon events tested, a rate consistent with previous reports using this platform (Du et al., 2010; Polymenidou et al., 2011; Sugnet et al., 2006) (See Figure 1E for select hnRNP A1-dependent events and Figure S1B–G for additional events tested). Splicing changes in 293T cells were reproduced when we depleted hnRNP A2/B1 with an antisense oligonucleotide in primary human fibroblasts (Figure S1H–I), indicating that the regulation of many of these AS events is preserved in primary human cells. Thus, we conclude that these 6 hnRNP proteins, act both as repressors and activators of exon inclusion, and are important for maintaining correct levels of inclusion of hundreds to thousands of differentially spliced AS events in the human transcriptome.

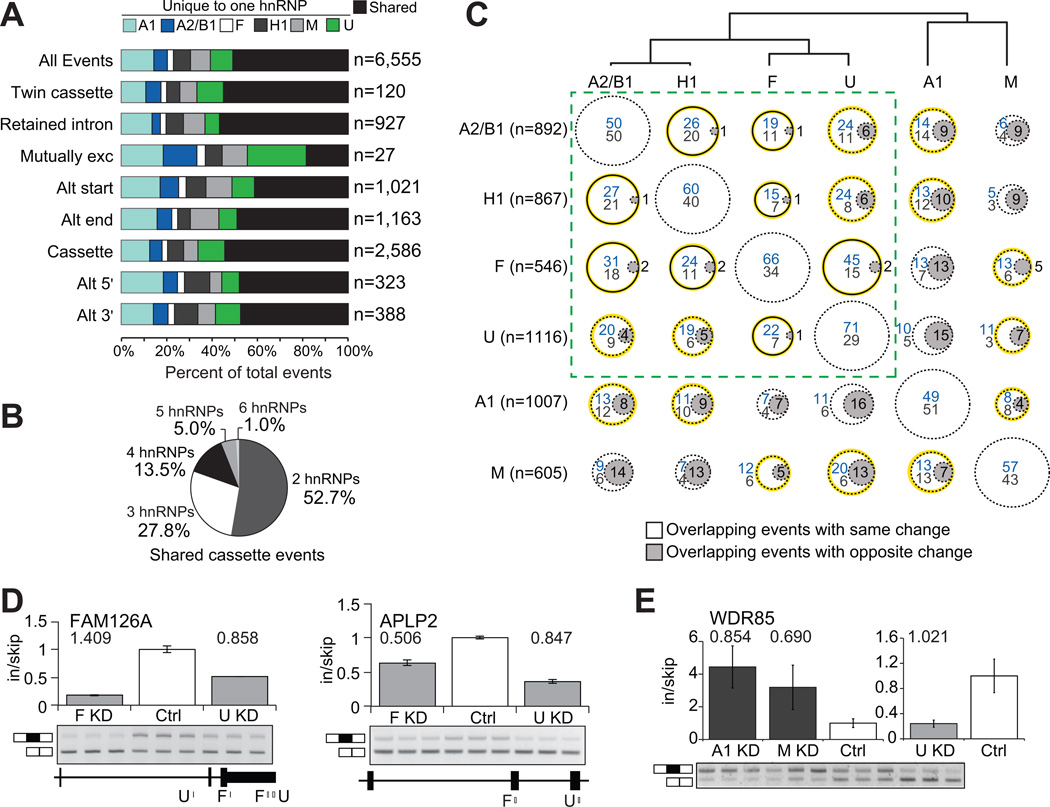

Multiple hnRNP proteins regulate a majority of AS events in a hierarchy of collaboration

The high abundance of hnRNP proteins in human cells suggests that a considerable level of multiplicity or redundancy is likely to exist to regulate RNA processing. Indeed, more than half (54%) of the 2,586 differentially spliced cassette exons were affected by more than 1 hnRNP protein (Figure 2A). Moreover, 47% of the 1,407 shared cassette exons were affected by 3 or more hnRNP proteins (Figure 2B), recapitulated also in the other types of AS events (Figure 2A). These global observations in human cells are confirmed by studies of individual AS events, such as the c-src cassette exon N1 which is regulated by hnRNP F, hnRNP H1, PTB (hnRNP I), and hnRNP A1 (Black, 2003), as well as a study of the hnRNP A/B subfamily in a Drosophila cell-line (Blanchette et al., 2009). Using thousands of AS events, our findings demonstrate that hnRNP proteins act in a concerted manner at many events in human cells.

Figure 2. Multiple hnRNP proteins co-regulate AS events.

(A) For each type of AS event, the percentage of events that was affected in more than one hnRNP depletion is in black, and the percentage of events that was affected uniquely in a single hnRNP depletion. (B) Distribution of shared cassette exons affected by 2 to 6 hnRNP proteins. (C) Comparisons of the overlap and directionality of cassette exons affected by pairs of hnRNP proteins. The dendrogram displays the hierarchical clustering of all cassette exons regulated by each hnRNP protein. Circles represent the percent of overlapping events for the hnRNP in the row, with the hnRNP listed in the column. Circles with gray shading indicate overlapping events that were affected in opposing directions (depletion of one hnRNP protein leads to inclusion and depletion of the other hnRNP leads to skipping). For cassette exons that were affected in the same direction, blue values indicates the percentage of events that were hnRNP-activated while values in gray listed below represent percentage that were hnRNP-repressed. The solid black lines represent significant overlap of targets (P < 0.05, hypergeometric test) and the yellow highlighting denotes overlapping cassettes that are significantly changing in the same direction (P < 0.002, hypergeometric test). The dashed-line box contains the hnRNP proteins that are most similar. (D) RT-PCR validations of cassette exons affected in the same direction upon depletion of hnRNP F or hnRNP U (P < 0.01, t-test). Binding of hnRNP F and U near the cassette exon is shown below. (E) RT-PCR validation of a cassette exon similarly affected by depletion of hnRNPA1 or hnRNP M, but opposite from the change caused by depletion of hnRNP U (P < 0.05, t-test). Absolute separation score as predicted by the splicing array analysis is listed above the bars. Bar plots represent densitometric analysis of bands and error bars are standard deviations in triplicate experiments (See also Figure S2).

We next set out to identify relationships between hnRNP proteins and the sets of cassette exons they regulate. Hierarchical clustering across regulated cassette exon sets revealed that activities of hnRNP A1 and M are the most distinct among the 6 hnRNP proteins (Figure 2C, dendrogram). To examine each relationship, we counted the percent of cassette exons regulated independently by pairs of hnRNP proteins, termed “overlapping events”. To illustrate, 29% of cassette exons affected by depletion of hnRNP M are also affected by depletion of hnRNP A2/B1 (Figure 2C row 6, column 1, sum of percentages), and correspondingly 19% of cassettes affected by depletion of hnRNP A2/B1 are also affected by M (Figure 2C row 1, column 6, sum of percentages). HnRNP F and H1 have very similar protein domain structures and bind to the same motif (Caputi and Zahler, 2001), which correlates with their significant fraction of overlapping events (206 total; P < 0.05, hypergeometric test). HnRNP A1 and A2/B1 also have similar protein domain structures; however, we only observed a modest fraction of overlapping events (330 total; Figure 2C). Instead, we observed significant fractions of overlapping events regulated between hnRNP proteins A2/B1 and H1, A2/B1 and F, and F and U (Figure 2C solid lined circles). These results identify novel relationships between hnRNP proteins in AS regulation.

To determine whether pairs of hnRNP proteins might act in concert or antagonistically, we noted the direction of change generated by each pair for each of their overlapping events. We found that most changed in the same direction (76% of targets, on average, across all pair-wise comparisons). In fact, a significant fraction of the changes in 11 of the 15 pair-wise comparisons of hnRNP-regulated cassette exons were in the same direction (P < 0.002, hypergeometric test; Figure 2C, highlighted in yellow), implying that multiple hnRNP proteins generally act in concert to modulate exon inclusion. Notably, 62% of the overlapping events between hnRNP F and H1 and 73% of the overlapping events between hnRNP F and U were activated upon depletion of either protein. RT-PCR confirmed 14 examples of cooperative AS regulation by hnRNP F and U, many with direct evidence for binding for the hnRNP proteins in the proximity of the exon (Figure 2D; Figure S2A). Of all pair-wise comparisons, hnRNP A1 and M regulated a more distinct set of cassette exons in comparison with the other hnRNP proteins, and they showed fewer overlapping events in the same direction (Figure 2C). We also validated 3 events where hnRNP A1 acted antagonistically to hnRNP U (Figure S2B), 2 events where hnRNP A1 and M acted similarly (Figure S2C), and 1 event where hnRNP A1 and M acted similarly, but antagonistically to hnRNP U (Figure 2E). We conclude that indirectly or directly, hnRNP proteins A2/B1, H1, F and U act cooperately to regulate AS in similar ways, while hnRNP proteins A1 and M influence changes in opposition from the other hnRNP proteins.

Mapping sites of physical interaction between 6 hnRNP proteins and ~10,000 pre-mRNAs

The complex regulation observed above could be achieved by a number of indirect mechanisms. To determine whether joint regulation by hnRNP proteins involves direct binding by multiple proteins, we identified RNA binding sites of the hnRNP proteins using CLIP-seq. HnRNP proteins have been shown to bind degenerate RNA sequences that are relatively short (~4–5 nucleotides in length), rendering identification of binding sites by solely bioinformatic means unreliable. Instead, CLIP employs immunoprecipitation of crosslinked protein-RNA complexes to purify and sequence RNA regions bound to the protein of interest, and despite inherent limitations of specificity common to immunoprecipitation based methods, CLIP has been successfully used to identify direct binding sites across many cell-types, tissues and organisms (Chi et al., 2009; Hafner et al., 2010; Konig et al., 2010; Licatalosi et al., 2008; Mukherjee et al., 2011; Polymenidou et al., 2011; Sanford et al., 2009; Yeo et al., 2009). We performed CLIP-seq for hnRNP A1, A2/B1, F, M, and U (Figure S3A, Table S1), yielding comparable results to data generated for hnRNP H1 (Katz et al., 2010), which we incorporated with our own to generate a complete set of CLIP-seq data for the hnRNP proteins of interest.

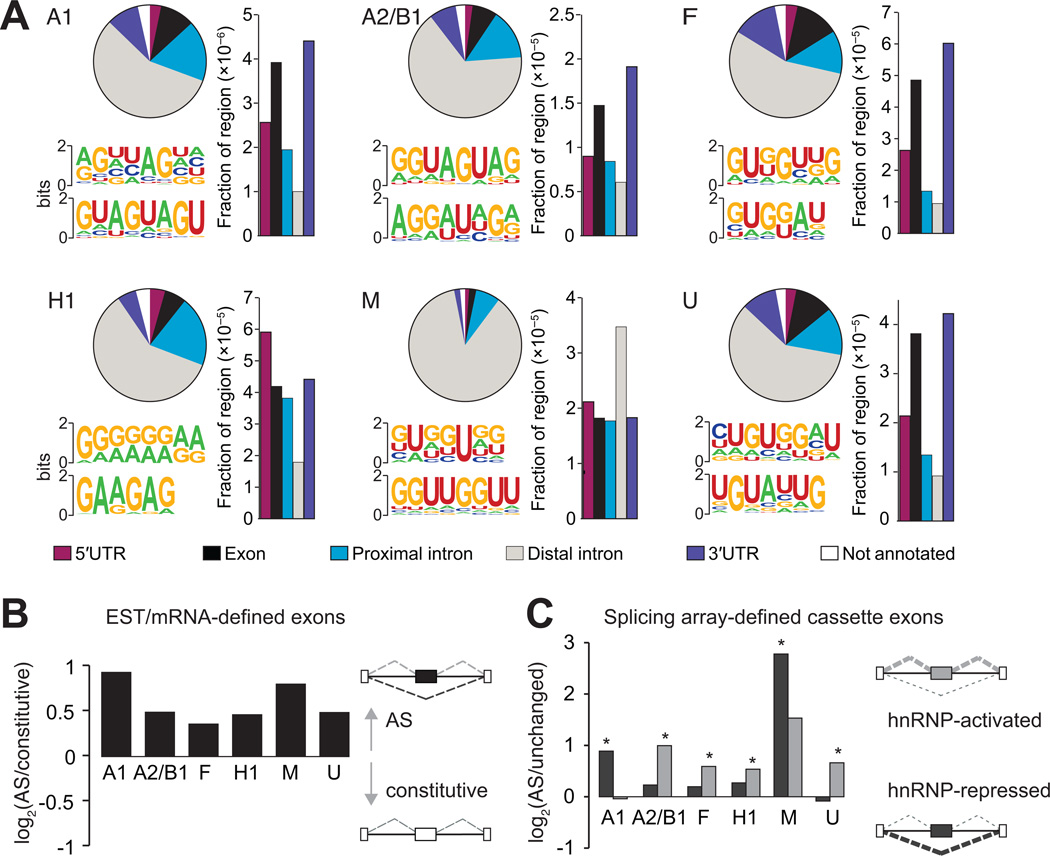

A total of 85,921 CLIP-derived clusters (CDCs) were identified, representing binding sites for 6 hnRNP proteins in 10,557 protein-coding genes (Table S1). These binding sites are distributed uniformly across pre-mRNA sequences, with the exception of hnRNP M, which shows a 5′ bias (Figure S3B). HnRNP binding sites are predominantly intronic, occurring within 500 nt of an exon, as expected for splicing regulators, but also in distal intronic regions (Figure 3A, pie charts). Accounting for the total length of the region reveals enrichment for binding within exonic regions and 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs) for hnRNP A1, A2/B1, F, and U (Figure 3A, bar plots). The enrichment is consistent with the continous shuttling of most hnRNP proteins from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and can mediate gene regulation via other RNA processing events such as transport and stability (Dreyfuss et al., 2002). HnRNP M demonstrates a stronger preference for binding in distal intronic regions, resembling that of another member of the hnRNP family, TDP-43, in mouse brain (Polymenidou et al., 2011). The distributions of hnRNP binding sites in different genic regions indicate that hnRNP proteins, in particular hnRNP M, are likely to have additional RNA processing functions other than splicing regulation.

Figure 3. HnRNP proteins bind to sequence motifs in vivo and are enriched near regulated exons.

(A) Distribution of hnRNP binding sites within different categories of genic regions (pie charts). Bar plots represent the fraction of a particular region bound, relative to the total genomic size of the region. The most representative top motifs identified by the HOMER algorithm are also shown. (B) Preference for hnRNP protein binding near expressed sequence tag (EST) or mRNA-defined cassette exons. The y-axis is the log2 ratio of the fraction of 41,754 cassette exons to the fraction of 222,125 constitutive exons harboring hnRNP binding clusters within 2 kilobases (kb) of the exon. All bars are significant (P < 10−28, Fisher exact test). (C) Preference for hnRNP proteins to bind proximal to splicing array-defined cassette exons that are activated or repressed by a specific hnRNP protein. The y-axis is the log2 ratio of the fraction of changed cassette exons to the fraction of unchanged cassette exons having hnRNP binding clusters within 2 kb of the exon. Dark gray bars represent the preference for hnRNP-repressed compared to unaffected exons and light gray bars represent the preference for hnRNP-activated compared to unaffected exons. A single asterisk denotes the most significant binding preference (P < 0.05, Fisher exact test). (See also Figure S3).

In vivo hnRNP sequence motifs and enrichment near regulated exons

HnRNP proteins frequently recognize degenerate RNA sequences, as determined from affinity purification and SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) experiments to identify the in vitro binding motif of the proteins (Burd and Dreyfuss, 1994; Swanson and Dreyfuss, 1988). The HOMER algorithm (Heinz et al., 2010) was applied to each set of hnRNP CDCs to discover the in vivo binding motifs of each hnRNP protein (two representatives of the four most significantly enriched motifs in Figure S3C are depicted in Figure 3A). For hnRNP A1, the predicted UAG(G) motif resembles the well-characterized UAGG hnRNP A1 binding site (Hutchison et al., 2002). For hnRNP A2/B1, not only did we we recover the UAG sequence among the most significantly enriched motifs, but we also identified a G/A-rich motif similar to the previously published UAGRGA motif (Hutchison et al., 2002). HnRNP F binds fairly G-rich sequences similar to the known in vitro GGGA motif (Caputi and Zahler, 2001). Additional G-rich motifs with interspersed uridines and adenosines are also enriched for hnRNP F, which is consistent with the motifs identified in SELEX experiments coupled with high-throughtput sequencing (Zefeng Wang, personal communication). HnRNP H1 binds G-rich sequences interspersed with adenosines, which is very similar to its known GGGA motif (Caputi and Zahler, 2001; Katz et al., 2010). HnRNP M binds to GU-rich sequences that often contain a UU sequence within the motif, collaborating with in vitro observations that hnRNP M interacts with poly-U and poly-G sequences (Datar et al., 1993). HnRNP U CDCs are enriched for GU-rich sequences, also in agreement with a previous report showing that poly-U and poly-G sequences were the preferred in vitro binding sequences for hnRNP U (Kiledjian and Dreyfuss, 1992).

Next, we studied hnRNP binding sites near all annotated exons categorized as either constitutive or AS based on available expressed sequence tag (EST) or mRNA transcript evidence. A distance of 2 kilobases (kb) up and downstream of the exon was chosen to capture the hnRNP interactions with the most potential to affect splicing. While individual hnRNP CDCs are associated with 5% of constitutive exons on average, a small but significantly higher 7% on average are observed for AS exons for each of the 6 hnRNP proteins (P < 10−28, Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 3B). Consistent with our finding that hnRNP proteins activate and also repress exon recognition, these results reveal that hnRNP proteins directly associate with constitutive, but more preferentially AS exons in human cells. Focusing on cassette exons that were hnRNP-activated (skipped upon hnRNP depletion) or hnRNP-repressed (included upon hnRNP depletion), we observed that an average of 11% of cassettes harbor a CDC of the regulating hnRNP within 2kb (Figure 3C; Figure S3D). Although it is likely that not all binding sites are retrieved by the CLIP procedure, we considered this subset of cassette exons direct targets of hnRNP proteins. Repeating our analysis with the quartile of cassette exons that change most strongly, corresponding to exons that are more uniquely regulated by a single hnRNP protein (Figure S3E), did not alter the fraction of direct targets (Figure S3F). In agreement with our pair-wise comparisons of microarray-detected AS cassette exons, we observe that hnRNP A1 and M more frequently bind near exons that are included upon depletion (P < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test), implicating these proteins in direct repression of exon inclusion (Figure 3C). In contrast, hnRNP proteins A2/B1, F, H1 and U appear to preferentially bind near exons skipped upon their depletion, implying that these proteins directly activate exon inclusion.

We also considered what fraction of a particular set of hnRNP-regulated cassettes contained binding sites for the other hnRNP proteins within 2kb of the event. Significant CDCs for any of the 6 hnRNP proteins fall within 2kb of 41% of regulated exons on average (Figure S3G), and CLIP-seq reads for any of the 6 hnRNP proteins fall within 2kb of 95% of regulated exons on average (Figure S3H). Furthermore, we observe that binding of a particular hnRNP to the exons that change upon its depletion is not significantly enriched over binding to the same exons by the other hnRNP proteins (Table S2). One notable exception to this observation is hnRNP M, which shows a 4-fold enrichment of binding to its regulated events over binding of other hnRNP proteins to hnRNP M regulated events. Interestingly, we also see a 2-fold enrichment of binding by hnRNP M and hnRNP A2/B1 to hnRNP A1-regulated events. These observations demonstrate that hnRNP proteins are likely in a dynamic but overlapping complex that cooperate highly in the regulation of AS.

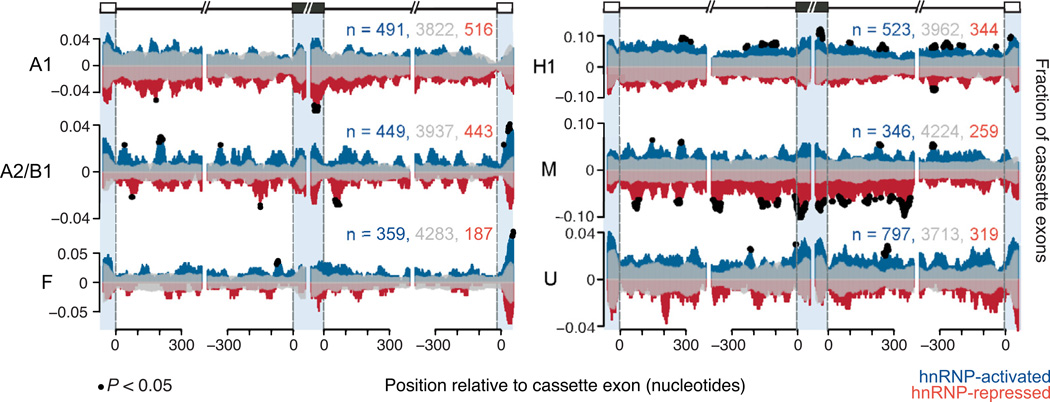

RNA splicing maps revealed for hnRNP proteins

To determine whether a pattern of position-dependent binding of the hnRNP proteins is associated with some aspect of AS, we computed the fraction of hnRNP-activated or hnRNP-repressed cassette exons that had an overlapping CLIP-seq read at each flanking nucleotide position. A similar calculation was used to determine the fraction of binding surrounding exons that remained unchanged during hnRNP depletion. A nonparametric statistical test was used to identify positions that were significantly enriched for hnRNP binding (Figure 4, black dots denote positions P < 0.05, chi-square test). This analysis revealed that each hnRNP had a unique pattern of binding around exons they directly regulate. For example, hnRNP A1 significantly bound the 3′ end of exons that were included upon depletion of hnRNP A1 (i.e., repressed). This observation is consistent with previous reports that hnRNP A1 binds exonic regions to repress usage of a nearby 5′ splice site (Martinez-Contreras et al., 2007). In contrast, we have shown that hnRNP A2/B1 preferentially binds activated more than repressed exons (Figure 3C), but is found at precise locations within ~150 nucleotides up and downstream of its repressed exons (Figure 4), suggestive of a “looping out” model of repression as proposed for the case of the hnRNP A1 pre-mRNA (Hutchison et al., 2002; Martinez-Contreras et al., 2006). HnRNP M binds proximal to and within exons to repress splicing (Figure 3C, Figure 4). HnRNP H1 binding is enriched within the flanking intronic regions of exons it activates, similar to a recently published study for hnRNP H1 (Katz et al., 2010). In contrast, we also observe hnRNP H1 binding to the exons it activates, consistent with previous findings that hnRNP H1 binds exons and activates exon inclusion (Caputi and Zahler, 2002; Chen et al., 1999). Unlike splicing factors that are more tissue-specific, such as the NOVA and RBFOX proteins, the RNA-maps for the hnRNP proteins appear less constrained proximal to the regulated exons (Licatalosi et al., 2008; Yeo et al., 2009). We also find that hnRNP proteins are neither enriched near exons that are alternatively spliced in a tissue specific manner (Figure S4), nor are they enriched near exons that are predicted to be alternatively spliced in both human and mouse (Figure S4, last column). This shows that hnRNP proteins are not preferentially selected to specify very tissue-specific or evolutionarily conserved alternative splicing events. This likely reflects a more general control of RNA metabolism by ubiquitously expressed hnRNP proteins that are dynamically in complex with overlapping activities, including but not limited to AS.

Figure 4. HnRNP proteins bind in a position-specific manner around cassette exons.

RNA splicing maps showing the fraction of microarray-detected cassette exons with CLIP-seq reads located proximal to activated (positive y-axis, blue), repressed (negative y-axis, red), and unaffected cassette exons (reflected on positive and negative y-axis, transparent gray). The x-axis represents nucleotide position relative to upstream, cassette and downstream exons. Blue shading separates positions that fall in the upstream exon (left, −50-0), in the cassette exon (middle left, 0–50, middle right, −50-0) and in the downstream exon (right, 0–50). Black dots represent nucleotide positions where significantly more hnRNP-activated cassette exons or hnRNP-repressed cassette exons showed binding, compared to unchanged cassette exons (P < 0.05, chi-square test). The total counts for activated, unaffected, and repressed exons that were used to generate the maps are listed. (See also Figure S4).

HnRNP proteins regulate RNA binding proteins

Gene ontology analysis of 715 hnRNP RNA targets bound by all 6 hnRNP proteins reveals that RNA processing, in particular the molecular process of “RNA splicing” (P = 2.63×10−8) and “mRNA metabolic process” (P = 9.11×10−9) are highly enriched categories. Interestingly, inspection of the list of genes that have CLIP-seq clusters reveals that hnRNP genes are targets of hnRNP proteins. Specifically, hnRNP A1, A2/B1, C, F, H, I, K, L, M, Q, R, and U were bound by at least one of the 6 hnRNP proteins assayed, and all of the hnRNP proteins assayed directly associated with their own transcript (Figure 5A). The hnRNP proteins often bound to the 3′UTRs of hnRNP transcripts, which suggests auto-regulation of their own and regulation of other hnRNP transcripts.

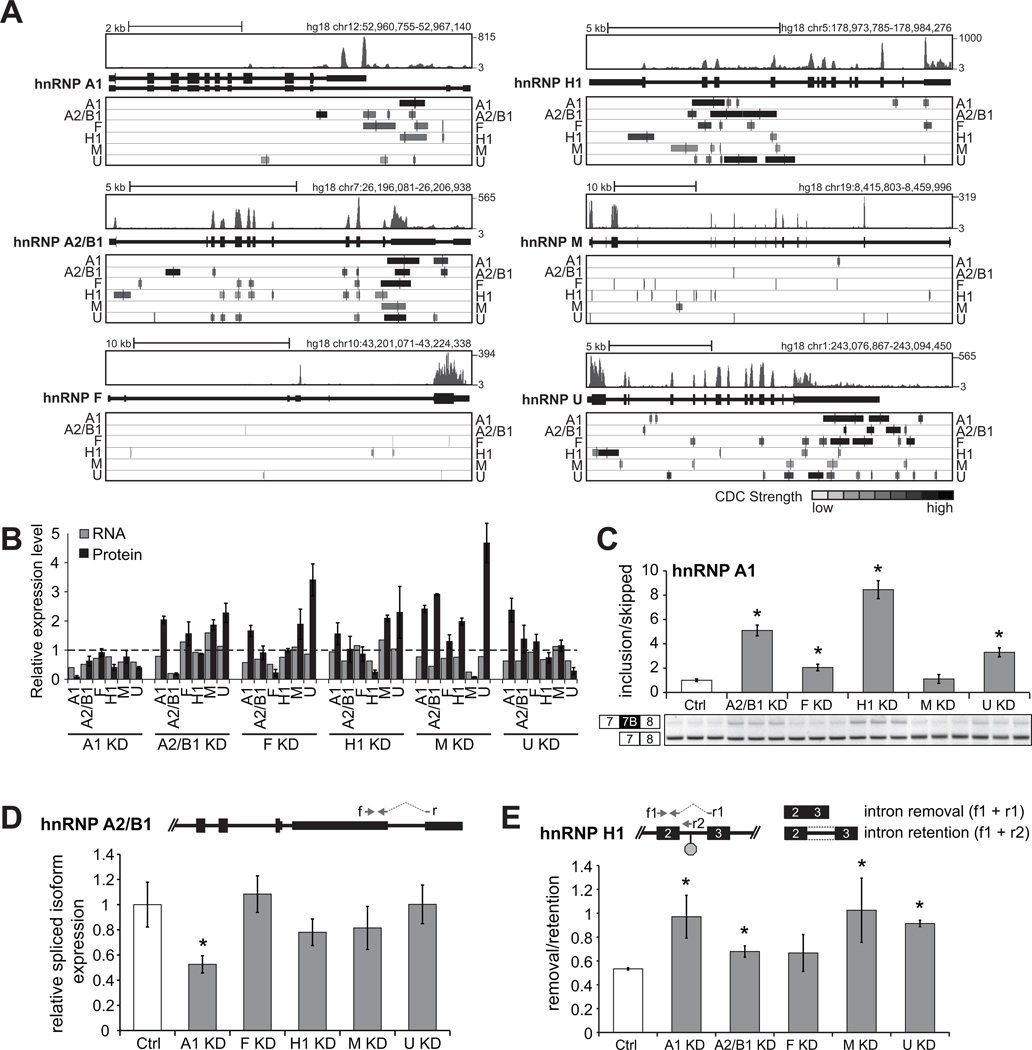

Figure 5. Cross-regulation of hnRNP proteins adds complexity to splicing regulation.

(A) CLIP-derived clusters (CDCs) identified for each hnRNP within each of the 6 hnRNP gene structures. CDCs are shaded according to strength of binding, where darker shading indicates more significant read coverage. RNA-seq read distributions in control siRNA treated 293T cells are shown above each hnRNP gene structure. (B) Quantification of hnRNP protein abundance (based on densitometric measurements of Figure S5 bands) and RNA abundance (based on RNA-seq RPKMs) within the context of the different hnRNP depletion conditions. Y-values are fold-changes over the control protein and RNA levels. (C) RT-PCR splicing validation of hnRNP A1 exon 7B in each of the hnRNP KD experiments. Bars represent densitometric measurements of bands relative to control. Significant changes relative to control are starred (P < 0.002, t-test). (D) Relative expression of an hnRNP A2/B1 spliced 3’UTR NMD candidate isoform in each of the hnRNP KD experiments. Primers ‘f’ and ‘r’ are depicted. Bars represent an average abundance by qRT-PCR across triplicate KD experiments, relative to control. All measurements were normalized to GAPDH expression. Significant changes relative to control are starred (P < 0.001, t-test). (E) Ratio of relative hnRNP H1 isoform expression with intron removed (measured with primers f1 and r1 depicted) compared to relative hnRNP H1 isoform expression with intron retained (measured with primers f1 and r2 depicted) in each of the hnRNP KD conditions. Bars represent an average abundance by qRT-PCR across triplicate KD experiments relative to control. All measurements are normalized to GAPDH expression. Asterisks denote significant changes relative to control (P < 0.04, t-test).

To measure the transcript levels of hnRNP genes and other targets which were not all represented on the splicing microarrays, we subjected polyA-selected RNA from the cells depleted of hnRNP expression to strand-specific RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (Parkhomchuk et al., 2009). For 25,921 annotated human genes, we computed the number of mapped reads per kilobase of exon, per million mapped reads (RPKM) as a normalized measure of gene expression in the hnRNP-depleted and the control siRNA treated 293T cells (Mortazavi et al., 2008). The RPKM values reflected reduced levels of the hnRNP transcripts, consistent with significant down-regulation at their protein level upon siRNA treatment (Figure 5B). Interestingly, in several cases we observed significant upregulation of other hnRNP proteins upon depletion of a specific hnRNP protein, such as depletion of hnRNP F leading to an increase in hnRNP U protein levels. This increase in protein levels, which is unlikely a result of off-target siRNA effects that would downregulate mRNA levels, appears to be post-transcriptional as relatively little changes in mRNA levels of the hnRNP genes were observed (Figure 5B). Our findings strongly suggest that compensatory relationships exist, supporting the cooperativity of binding and regulation among the hnRNP proteins. The observation that these compensatory reactions are asymmetric (i.e. hnRNP F does not increase upon hnRNP U depletion) also reveals further complexity in their relationships. Furthermore, our results here imply that the alternative splicing changes we discovered using the microarrays are likely an underestimate of the AS events that are regulated by an individual hnRNP protein due to compensation between hnRNP proteins.

We next explored specific examples of auto- and cross-regulation of hnRNP proteins. HnRNP A1 has been shown to bind in vitro and regulate the skipping of its own cassette exon 7B (Blanchette and Chabot, 1999). The hnRNP A1 isoform containing exon 7B yields a protein with less splicing activity (Mayeda et al., 1994). Close to this exon in the hnRNP A1 transcript, we find an hnRNP U binding site (Figure 5A), suggesting that hnRNP U may also contribute to the splicing of exon 7B. Indeed, using RT-PCR to detect the splicing of exon 7B upon hnRNP U depletion confirms that hnRNP U represses the recognition of exon 7B (Figure 5C, P < 0.002, t-test). Interestingly, we also find that hnRNP A2/B1, F, and H1 repress this exon, perhaps indirectly, as there was no significant binding evidence for these hnRNP proteins, nor hnRNP A1, near the event in vivo in these cells.

HnRNP A2/B1 has been shown to autoregulate its own expression levels by splicing of an intron within its 3′UTR that subsequently results in nonsense mediated decay (NMD) of the RNA transcript (McGlincy et al., 2010). Using a splicing-sensitive quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) strategy, we demonstrate that hnRNP A1 also contributes to the splicing of the hnRNP A2/B1 3′UTR, implicating hnRNP A1 in the regulation of hnRNP A2/B1 (Figure 5D, P < 0.001, t-test). This splicing event in the hnRNP A2/B1 3′UTR is directly bound only by hnRNP A2/B1 and hnRNP A1, indicating that the regulation is specific and direct (Figure 5A). Previous work has proposed that RBPs often facilitate splicing changes within other RBPs to yield NMD candidate transcripts as a mechanism of homeostatic control (Ni et al., 2007). These events can also occur through the inclusion of an intron or exon containing a premature termination codon (PTC). We also tested another NMD candidate event where an intron is retained in the hnRNP H1 transcript resulting in an in-frame PTC. This region is of particular interest because it is stongly bound by hnRNP A1, A2/B1, F, M, and U (Figure 5A). Using qRT-PCR we measured the ratio of the hnRNP H1 isoforms, one with the intron removed and the other with the intron retained. Our results reveal that hnRNP A1, A2/B1, M and U affect the inclusion of this intron in hnRNP H1 (Figure 5E, P < 0.04, t-test). Notably, the regulation of hnRNP H1 by hnRNP M correlates with an increase in H1 protein levels upon depletion of hnRNP M (Figure 5B). We conclude that in addition to previous literature that hnRNP proteins are subject to auto-regulation (Blanchette and Chabot, 1999; McGlincy et al., 2010; Rossbach et al., 2009), hnRNP proteins cross-regulate each other, adding to the complexity of the cooperative regulation of AS by the hnRNP proteins.

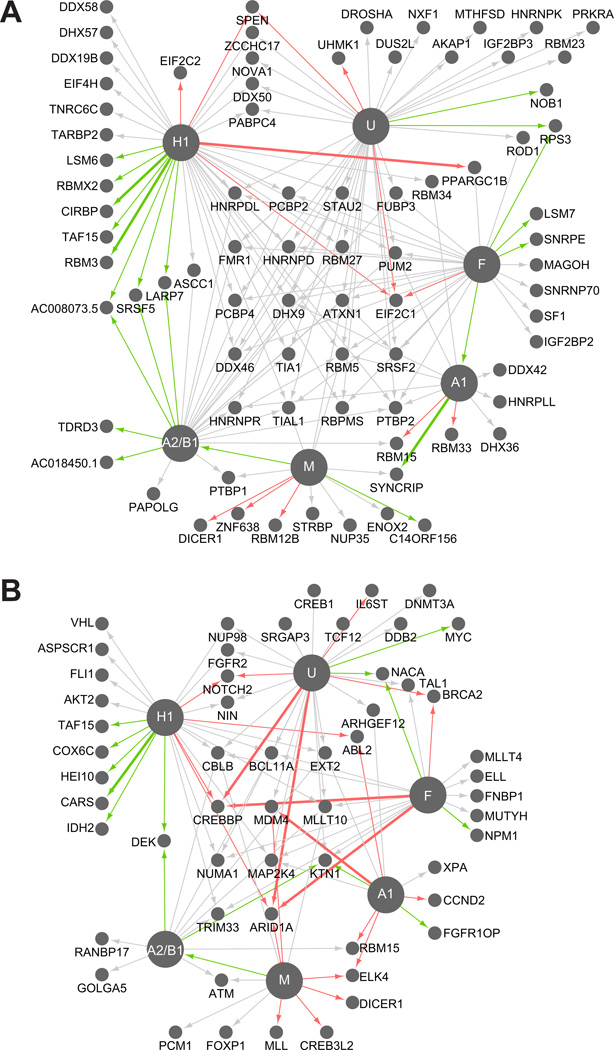

Aside from hnRNP genes, other splicing factors from the SR protein family such as SRSF1–7 were also direct targets, containing a CDC of at least 1 hnRNP protein assayed. To identify if other pre- or mRNA binding proteins were direct targets, we compiled a list of 443 genes containing RNA binding domains predicted to bind pre-mRNA and mRNA. Interestingly, 70% of the identified RBPs (311 of 443) are bound by at least one hnRNP protein (P < 1.5×10−36, hypergeometric test). Therefore, hnRNP proteins interact with the RNAs of a significant proportion of all RBPs. Furthermore, this number of bound RBPs is likely an underestimate, as hnRNP binding for cell-specific or lowly abundant RBP transcripts may have been missed. HnRNP proteins also regulate a significant subset of the RNAs encoding RNA binding proteins (82 of the 311 to which they are bound), at either the expression or AS level as detected by splicing array (P < 1.5×10−5, hypergeometric test) (Figure 6A). Intriguingly, we detect regulation of RBPs important for the microRNA pathway including Drosha, Dicer1, EIF2C1 (Ago1), EIF2C2 (Ago2) and also other splicing factors including, PTBP1 and 2, SRSF5, NOVA1, and other hnRNP proteins D, DL, K, Q (Syncrip) and R. For RBP transcripts that are bound and regulated by multiple hnRNP proteins at the expression level, we consistently see that all hnRNP proteins tested affect the transcripts in the same direction, all causing down-regulation or all causing up-regulation. These findings demonstrated that hnRNP proteins have regulatory responsibilities, and likely play roles in managing mRNA levels of other RNA binding proteins important for AS and microRNA-mediated silencing.

Figure 6. HnRNP proteins regulate other RBPs and cancer-associated transcripts.

Connectivity diagrams of hnRNP-regulated and hnRNP-bound (A) RNA binding protein transcripts or (B) cancer-associated transcripts. Nodes represent hnRNP RNA targets and the hnRNP nodes are enlarged for emphasis. Each edge represents an hnRNP target that is both bound directly and regulated, colored according to the type of regulation. Gray represents that the gene contains a cassette exon that changes upon depletion of the hnRNP. Red and green edges reflect up and down-regulation of mRNA levels upon depletion of the hnRNP. Thicker edges represent genes with both an alternative cassette and an expression change. (See also Figure S6)

Cancer-associated genes are direct targets of hnRNP proteins

In our analysis of hnRNP-bound transcripts, we also observed strong enrichment for the gene ontology terms “cell cycle” (P < 1.38×10−22) and “response to DNA damage stimulus” (P < 1.19×10−18). Widespread misregulation of AS has been observed in several types of cancer including lung (Misquitta-Ali et al., 2011), breast (Lapuk et al., 2010), and colon cancer (Gardina et al., 2006). Underlying this effect on AS is likely the misregulation of the levels of hnRNP proteins in cancer (Carpenter et al., 2006). To identify hnRNP-regulated AS events within cancer-associated genes, we identified all hnRNP-regulated cassette exons within a set of 368 genes where specific mutations in these genes are known to contribute to oncogenesis (Futreal et al., 2004). We found 77 hnRNP-regulated cassette exons that occurred specifically in these genes, as determined by the splicing array. Using the Fluidigm microfluidic multiplex qRT-PCR platform, we independently validated 41 of the cancer-associated splicing events (Figure S6).

As hnRNP proteins may bind to targets to regulate other aspects of RNA processing or other AS events that the arrays were not designed to interrogate, we searched the 368 cancer-associated genes for direct hnRNP binding to their pre-mRNAs. This experiment shows that 71% of the Sanger cancer-associated genes (261 of 368) have pre-mRNAs that are bound by at least one hnRNP protein (P < 5.3×10−32, hypergeometric test) and 57 of the 261 are significantly regulated by the bound hnRNP at the expression level and/or the AS level (causing a change in inclusion of a cassette exon upon depletion of an hnRNP; P < 0.04, hypergeometric test; Figure 6B). Of the 46 cancer-associated AS events that are regulated by multiple hnRNP proteins, 39 (85%) are regulated by all hnRNP proteins in the same splicing direction. This trend again highlights our finding that many hnRNP proteins regulate RNA processing in a concerted manner, and suggests that hnRNP proteins may cooperate and have redundant roles to maintain normal cellular homeostasis, disruption of which can lead to cancer.

DISCUSSION

Cooperative regulation by hnRNP proteins

The precise control of RNA processing by RBPs is essential for maintaining correct gene expression, defects of which can lead to genetic diseases such as ALS, Fragile X syndrome, as well as cancer (Carpenter et al., 2006; Lagier-Tourenne et al., 2010; Melko and Bardoni, 2010). With the emergence of genome-wide methods for detecting direct binding of RBPs on their RNA substrates, coupled with technologies to measure changes in RNA processing genome-wide, a new understanding of the global function of individual RBPs is emerging. Here we present a genome-wide analysis that integrates regulation and binding information for six highly abundant and ubiquitously expressed RNA binding proteins in human cells. We have identified 6,555 AS events regulated by six major hnRNP proteins, A1, A2/B1, H1, F, M, and U, representing the largest set of RBP-regulated human exons demonstrated thus far. With this data we have established that these members of the hnRNP family seem to cooperate with each other in a finely connected network of regulation, a discovery that would likely be missed in analysis of a single hnRNP protein.

The hnRNP protein family was first grouped together based on their abundance and ability to crosslink to RNA, however recent studies have debated that perhaps the hnRNP proteins acted too dissimilarly to be grouped into the same family (Han et al., 2010). Here we have shown that the hnRNP proteins are similar and cooperative in their regulatory roles, with significant overlap of their bound RNA targets and also in regulation of sets of AS exons. This is in contrast to the study in Drosophila of the hnRNP A/B sub-family, which identified only partial overlapping hnRNP-bound targets (Blanchette et al., 2009). Interestingly, of common cassette exon targets, we observed a concordance of effects by hnRNP proteins A2/B1, F, H1 and U, and opposing effects by hnRNP proteins A1 and M. Thus our genome-wide datasets reveal new insights governing the cooperativity of hnRNP proteins. Also, resonating with previous studies (Licatalosi et al., 2008; Mukherjee et al., 2011; Polymenidou et al., 2011; Sanford et al., 2009; Yeo et al., 2009), we identified that the hnRNP proteins targeted their own, and in several cases shown here, other hnRNP pre-mRNAs, as well as other RBP transcripts. This regulation of many RBPs, including many splicing factors (Figure 6B), has the potential to yield a cascade of direct and also indirect splicing changes in human cells when a single hnRNP is depleted. Consistent with this idea, we have found that on average less than 50% of the cassette exons have direct evidence for hnRNP binding (Figure S3G), suggesting that a portion of the molecular changes we have observed may be due to downstream regulation of other regulatory factors. For example, hnRNP F regulates the elongation factor ELL (Figure 6B), which in turn could impact a broader network of RNA processing factors via Polymerase II elongation-coupled effects on AS (Ip et al., 2011). Further saturation of our CLIP-seq libraries in the future may provide more evidence for bound targets. The absence of detectable hnRNP binding sites may also be due to the variability of UV cross-linking efficiency. A smaller scale study in human cells previously suggested potential cross-regulation between the hnRNP proteins and other RNA binding proteins, albeit without direct protein-RNA evidence to support their conclusions (Venables et al., 2008). In contrast, this wide-spread cross-regulation was not observed in Drosophila cell-lines (Blanchette et al., 2009), nor in another study of a splicing factor, RBFOX1 in mouse brains (Gehman et al., 2011). RNA processing, and AS in particular is likely far more complex in human, especially for the abundant, ubiquitously expressed RBPs like the hnRNP protein family. Integrated with AS information, our binding data has also enabled us to build splicing RNA maps that, as a whole, support that combinatorial control by hnRNP proteins could be achieved through direct binding of certain hnRNP proteins, followed by the coordination and recruitment of other hnRNP proteins to nearby, weakly bound sites (Blanchette et al., 2009).

Targets of hnRNP proteins enriched in cancer pathways

Consistent with the increasing evidence that hnRNP proteins contribute to cancer pathogenesis, we have discovered that cancer-associated genes are direct and regulated targets. While hnRNP proteins have been directly linked to cancer, their specific mechanisms for affecting tumorigenesis largely remain to be identified. Here, we have provided a glimpse into what cancer-related pathways may be specifically targeted in cancers. The direct mechanism in which the hnRNP proteins interact with these genes and affect cancer progression remains to be further examined. We have provided a web resource (http://rnabind.ucsd.edu/) that enables users to upload sequences within protein-coding genes, which will be automatically inspected for hnRNP binding and regulation of AS within the gene. Taken together, the thousands of hnRNP regulated splicing changes that we have identified have the potential to provide insight into hnRNP-regulated splicing events in cancer and other disease systems.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

HnRNP A1, A2/B1, F, H1, M and U were individually depleted in human 293T cells by transfecting siRNAs at a final concentration of 100nM (Table S3 for all siRNA sequences) using Lipofectamine-2000 (Invitrogen). Transfections were repeated 48 hrs later and cells were harvested in TRIzol (Invitrogen) 72 hrs after the first transfection. Extracted RNA was subjected to splice-sensitive microarrays and strand-specific RNA-seq, prepared based on a previously described method (Parkhomchuk et al., 2009) with minor modifications (See Supplemental Experimental Procedures). To acquire RNA targets, untreated human 293T cells were subjected to UV cross-linking and the frozen lysates were subjected to the CLIP-seq protocol for hnRNP A1, A2/B1, F, M, or U as previously described (Yeo et al., 2009), using anti-hnRNP A1 (Novus Biologicals), anti-hnRNP A2/B1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-hnRNP F (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-hnRNP M (Aviva Systems Biology), or anti-hnRNP U (Bethyl Laboratories), respectively. RNA libraries were subjected to standard Illumina sequencing. Details of computational analyses are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. All data (splicing arrays, CLIP-seq and RNA-seq) are deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE34992.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Thousands of binding sites and splicing events identified for major hnRNP proteins. (84/85 characters)

HnRNP proteins act cooperatively, regulating cassette exons in similar directions. (85/85 characters)

HnRNP proteins cross and auto-regulate. (65/85 characters)

HnRNP proteins regulate other RNA binding proteins and cancer related genes. (82/85 characters)

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Douglas Black, Zefang Wang and members of the Yeo lab, especially T. Stark, for critical reading of the manuscript. S.C.H. is funded by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. G.W.Y is an Alfred P. Sloan research fellow. This work was supported by grants from US National Institutes of Health (HG004659 and GM084317) and the Stem Cell Program at the University of California, San Diego. We would also like to thank Zefang Wang, Jens Lykke-Andersen, and ISIS Pharmacueticals for sharing reagents and unpublished results, as well as Fluidigm of South San Francisco, CA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette M, Chabot B. Modulation of exon skipping by high-affinity hnRNP A1-binding sites and by intron elements that repress splice site utilization. EMBO J. 1999;18:1939–1952. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette M, Green RE, MacArthur S, Brooks AN, Brenner SE, Eisen MB, Rio DC. Genome-wide analysis of alternative pre-mRNA splicing and RNA-binding specificities of the Drosophila hnRNP A/B family members. Mol Cell. 2009;33:438–449. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd CG, Dreyfuss G. RNA binding specificity of hnRNP A1: significance of hnRNP A1 high-affinity binding sites in pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1994;13:1197–1204. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi M, Zahler AM. Determination of the RNA binding specificity of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) H/H'/F/2H9 family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43850–43859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi M, Zahler AM. SR proteins and hnRNP H regulate the splicing of the HIV-1 tev-specific exon 6D. EMBO J. 2002;21:845–855. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B, MacKay C, Alnabulsi A, MacKay M, Telfer C, Melvin WT, Murray GI. The roles of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins in tumour development and progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1765:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CD, Kobayashi R, Helfman DM. Binding of hnRNP H to an exonic splicing silencer is involved in the regulation of alternative splicing of the rat beta-tropomyosin gene. Genes Dev. 1999;13:593–606. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datar KV, Dreyfuss G, Swanson MS. The human hnRNP M proteins: identification of a methionine/arginine-rich repeat motif in ribonucleoproteins. Nucleic acids research. 1993;21:439–446. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David CJ, Chen M, Assanah M, Canoll P, Manley JL. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 2010;463:364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss G, Kim VN, Kataoka N. Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss G, Matunis MJ, Pinol-Roma S, Burd CG. hnRNP proteins and the biogenesis of mRNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:289–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Cline MS, Osborne RJ, Tuttle DL, Clark TA, Donohue JP, Hall MP, Shiue L, Swanson MS, Thornton CA, et al. Aberrant alternative splicing and extracellular matrix gene expression in mouse models of myotonic dystrophy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, Rahman N, Stratton MR. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardina PJ, Clark TA, Shimada B, Staples MK, Yang Q, Veitch J, Schweitzer A, Awad T, Sugnet C, Dee S, et al. Alternative splicing and differential gene expression in colon cancer detected by a whole genome exon array. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehman LT, Stoilov P, Maguire J, Damianov A, Lin CH, Shiue L, Ares M, Jr, Mody I, Black DL. The splicing regulator Rbfox1 (A2BP1) controls neuronal excitation in the mammalian brain. Nat Genet. 2011;43:706–711. doi: 10.1038/ng.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan-Gerstl R, Cohen M, Shilo A, Suh SS, Bakacs A, Coppola L, Karni R. Splicing Factor hnRNP A2/B1 Regulates Tumor Suppressor Gene Splicing and Is an Oncogenic Driver in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4464–4472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jr, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SP, Tang YH, Smith R. Functional diversity of the hnRNPs: past, present and perspectives. Biochem J. 2010;430:379–392. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison S, LeBel C, Blanchette M, Chabot B. Distinct sets of adjacent heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1/A2 binding sites control 5' splice site selection in the hnRNP A1 mRNA precursor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29745–29752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip JY, Schmidt D, Pan Q, Ramani AK, Fraser AG, Odom DT, Blencowe BJ. Global impact of RNA polymerase II elongation inhibition on alternative splicing regulation. Genome research. 2011;21:390–401. doi: 10.1101/gr.111070.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima T, Manley JL. A negative element in SMN2 exon 7 inhibits splicing in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet. 2003;34:460–463. doi: 10.1038/ng1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz Y, Wang ET, Airoldi EM, Burge CB. Analysis and design of RNA sequencing experiments for identifying isoform regulation. Nat Methods. 2010;7:1009–1015. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiledjian M, Dreyfuss G. Primary structure and binding activity of the hnRNP U protein: binding RNA through RGG box. The EMBO journal. 1992;11:2655–2664. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig J, Zarnack K, Rot G, Curk T, Kayikci M, Zupan B, Turner DJ, Luscombe NM, Ule J. iCLIP reveals the function of hnRNP particles in splicing at individual nucleotide resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R46–R64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapuk A, Marr H, Jakkula L, Pedro H, Bhattacharya S, Purdom E, Hu Z, Simpson K, Pachter L, Durinck S, et al. Exon-level microarray analyses identify alternative splicing programs in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:961–974. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licatalosi DD, Mele A, Fak JJ, Ule J, Kayikci M, Chi SW, Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Blume JE, Wang X, et al. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature. 2008;456:464–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorian M, Schwartz S, Clark TA, Hollander D, Tan LY, Spellman R, Gordon A, Schweitzer AC, de la Grange P, Ast G, et al. Position-dependent alternative splicing activity revealed by global profiling of alternative splicing events regulated by PTB. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Contreras R, Cloutier P, Shkreta L, Fisette JF, Revil T, Chabot B. hnRNP proteins and splicing control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;623:123–147. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77374-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Contreras R, Fisette JF, Nasim FU, Madden R, Cordeau M, Chabot B. Intronic binding sites for hnRNP A/B and hnRNP F/H proteins stimulate pre-mRNA splicing. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda A, Munroe SH, Caceres JF, Krainer AR. Function of conserved domains of hnRNP A1 and other hnRNP A/B proteins. EMBO J. 1994;13:5483–5495. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlincy NJ, Tan LY, Paul N, Zavolan M, Lilley KS, Smith CW. Expression proteomics of UPF1 knockdown in HeLa cells reveals autoregulation of hnRNP A2/B1 mediated by alternative splicing resulting in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:565. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melko M, Bardoni B. The role of G-quadruplex in RNA metabolism: involvement of FMRP and FMR2P. Biochimie. 2010;92:919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misquitta-Ali CM, Cheng E, O'Hanlon D, Liu N, McGlade CJ, Tsao MS, Blencowe BJ. Global profiling and molecular characterization of alternative splicing events misregulated in lung cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:138–150. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00709-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee N, Corcoran DL, Nusbaum JD, Reid DW, Georgiev S, Hafner M, Ascano M, Jr, Tuschl T, Ohler U, Keene JD. Integrative Regulatory Mapping Indicates that the RNA-Binding Protein HuR Couples Pre-mRNA Processing and mRNA Stability. Mol Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni JZ, Grate L, Donohue JP, Preston C, Nobida N, O'Brien G, Shiue L, Clark TA, Blume JE, Ares M., Jr Ultraconserved elements are associated with homeostatic control of splicing regulators by alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated decay. Genes Dev. 2007;21:708–718. doi: 10.1101/gad.1525507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhomchuk D, Borodina T, Amstislavskiy V, Banaru M, Hallen L, Krobitsch S, Lehrach H, Soldatov A. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Huelga SC, Moran J, Liang TY, Ling SC, Sun E, Wancewicz E, Mazur C, et al. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:459–468. doi: 10.1038/nn.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossbach O, Hung LH, Schreiner S, Grishina I, Heiner M, Hui J, Bindereif A. Auto- and cross-regulation of the hnRNP L proteins by alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1442–1451. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01689-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford JR, Wang X, Mort M, Vanduyn N, Cooper DN, Mooney SD, Edenberg HJ, Liu Y. Splicing factor SFRS1 recognizes a functionally diverse landscape of RNA transcripts. Genome Res. 2009;19:381–394. doi: 10.1101/gr.082503.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugnet CW, Srinivasan K, Clark TA, O'Brien G, Cline MS, Wang H, Williams A, Kulp D, Blume JE, Haussler D, et al. Unusual intron conservation near tissue-regulated exons found by splicing microarrays. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson MS, Dreyfuss G. Classification and purification of proteins of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles by RNA-binding specificities. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2237–2241. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables JP, Koh CS, Froehlich U, Lapointe E, Couture S, Inkel L, Bramard A, Paquet ER, Watier V, Durand M, et al. Multiple and specific mRNA processing targets for the major human hnRNP proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6033–6043. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00726-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Zhou Y, Wu T, Zhu T, Ji X, Kwon YS, Zhang C, Yeo G, Black DL, Sun H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of PTB-RNA interactions reveals a strategy used by the general splicing repressor to modulate exon inclusion or skipping. Mol Cell. 2009;36:996–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo GW, Coufal NG, Liang TY, Peng GE, Fu XD, Gage FH. An RNA code for the FOX2 splicing regulator revealed by mapping RNA-protein interactions in stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:130–137. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.