Abstract

Liver preconditioning (PC), defined as an enhanced tolerance to injuring stimuli induced by previous specific maneuvers triggering beneficial functional and molecular changes, is of crucial importance in human liver transplantation and major hepatic resection. For these reasons, numerous PC strategies have been evaluated in experimental models of ischemia-reperfusion liver injury, which have not been transferred to clinical application due to side effects, toxicity and difficulties in implementation, with the exception of the controversial ischemic PC. In recent years, our group has undertaken the assessment of alternate experimental liver PC protocols that might have application in the clinical setting. These include thyroid hormone (T3), n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LCPUFA), or iron, which suppressed liver damage due to the 1 h ischemia-20 h reperfusion protocol. T3, n-3 LCPUFA and iron are hormetic agents that trigger biologically beneficial effects in the low-dose range, whose multifactorial mechanisms of action are discussed in the work.

Keywords: Liver preconditioning, Thyroid hormone, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, Iron

INTRODUCTION

Liver functioning is characterized by a multiplicity of processes that include most of the pathways for intermediary metabolism, biotransformation of xenobiotics, plasma protein biosynthesis, excretion and secretion of various types of molecules. With the exception of hyperglycemic conditions, the high energy requirements to support liver functions are primarily met by fatty acid oxidation, making the liver highly dependent on O2 supply and susceptible to hypoxic or anoxic conditions. Liver damage underlying cellular death is associated with cholestasis, viral hepatitis, drug-induced injury, obesity[1] and ischemia-reperfusion (IR) episodes, including liver transplantation, hepatic resection, low-blood pressure conditions and abdominal surgery requiring hepatic vascular occlusion[2-5]. IR injury is a phenomenon in which cellular damage due to hypoxia is exacerbated following restoration of O2 and nutrient supply[2-5]. In these situations, different types of ischemia can occur in the liver: namely, (1) warm ischemia inducing hepatocyte and sinusoidal endothelial cell (SEC) death, a feature of hepatic trauma, hypovolemic shock and inflow occlusion during liver surgery; and (2) cold ischemia leading to SEC death observed in liver transplantation after harvesting and preservation, which might involve rewarming ischemia during vascular anastomosis[6]. IR liver injury is due to numerous contributory factors, including Kupffer cell activation, oxidative stress and up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling, which often determine hepatic failure[1-6]. Considering that IR liver injury is a major complication in clinical practice due to its complexity in terms of molecular and cellular mechanisms, strategies reducing IR injury have been extensively studied[4-8].

In general terms, organ preconditioning (PC) is defined as an increased tolerance to IR injury afforded by previous specific maneuvers triggering beneficial functional and molecular changes, a phenomenon initially described by Murry et al[9] in the heart. PC strategies evaluated in experimental models of IR liver injury include: (1) pharmacological approaches targeting tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) response, mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, microcirculatory disorders or neutrophil infiltration; (2) gene therapy directed to up-regulation of proteins abrogating ROS production, apoptosis and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation or down-regulating of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and P-selectin expression reducing neutrophil recruitment; and (3) surgical strategies such as ischemic preconditioning (IP) or other strategies underlying moderate oxidative stress development (for specific references see[4-8,10]). The latter group of PC maneuvers includes development of hyperthermia[11], hyperbaric oxygen therapy[12] or the administration of the model oxidants tert-butyl hydroperoxide[13], doxorubicin[14] and ozone[15]. However, due to toxicity, side effects and difficulties in implementation, these experimental PC strategies have not been transferred to clinical application, with the exception of IP[6,16]. Although IP proved to be useful in human liver resections[17-19] and in human liver transplantation[20-22], this PC maneuver remains controversial[23-25]. For these reasons, our group has recently undertaken the evaluation of alternate experimental liver PC strategies that might have application in the clinical setting; namely, administration of thyroid hormone (L-3,3,,5-triiodothyronine, T3)[26], n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LCPUFA)[27] or iron[28], prior to an IR protocol.

THYROID HORMONE LIVER PRECONDITIONING

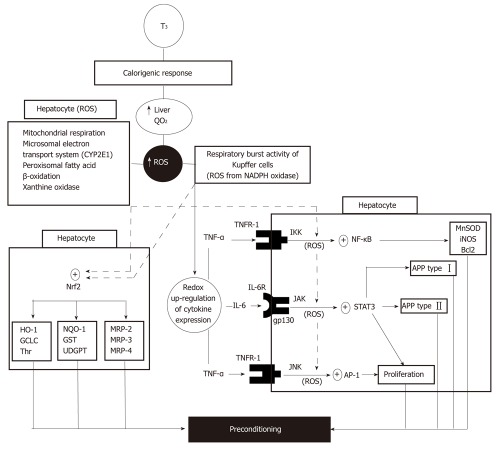

Liver PC by in vivo T3 administration is based on the calorigenic action of thyroid hormones leading to stimulation and maintenance of basal thermogenesis[29], a response that is carried out through genomic and non-genomic signaling mechanisms[1,30]. In the liver, this effect is evidenced by enhancement in the rate of O2 consumption, with consequent increment in ROS generation[31,32] by mechanisms primarily triggered in hepatocytes and in Kupffer cells (Figure 1). ROS produced in Kupffer cells activate redox-sensitive transcription factors such as NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) or activating protein 1 (AP-1), as shown by suppression of T3-induced DNA binding of these proteins by in vivo pretreatment with the antioxidants α-tocopherol and N-acetylcysteine or the Kupffer cell inactivator gadolinium chloride[1,30]. Under these conditions, activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in Kupffer cells is associated with up-regulation of the expression of genes for the cytokines TNFα, interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6[33], with enhanced synthesis and release into hepatic sinusoids (Figure 1). Interaction of Kupffer cell-derived TNF-α with TNF receptor 1 may trigger two responses in hepatocytes[33]: namely, (1) NF-κB activation via inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK) phosphorylation leading to the expression of antioxidant (manganese superoxide dismutase, inducible nitric oxide synthase), anti-apoptotic (Bcl2) and type I acute-phase (haptoglobin) proteins[34,35]; and (2) AP-1 activation via c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation leading to up-regulation of hepatocyte proliferation[36] (Figure 1). In addition, interaction of Kupffer cell-derived IL-6 with IL-6 receptor through its binding to the gp130 receptor subunit[37] may activate Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT3 system and the transcription of both type I (haptoglobin) and type II (β-fibrinogen) acute-phase protein genes[35] (Figure 1). Activation of NF-κB, STAT3 and AP-1 by Kupffer cell-derived TNF-α and IL-6 may be reinforced by ROS generated within hepatocytes by different enzymatic mechanisms triggered by T3 (Figure 1). These cytoprotective responses could be contributed by additional processes triggered by T3 administration: including (1) post-transcriptional up-regulation of the acute-phase protein ferritin through increased iron-induced displacement of iron regulatory protein from the iron-responsive element in ferritin mRNA[38]; and (2) transcriptional up-regulation of uncoupling proteins via the classical genomic pathway[39], which have been proposed to decrease the pro-oxidant potential of the liver[38-40].

Figure 1.

Redox signaling in T3 liver preconditioning is mediated by activation of transcription factors nuclear factor-κB, activating protein 1, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 triggering antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, acute-phase and proliferative responses. AP-1: Activating protein 1; APP: Acute-phase protein; CYP2E1: Cytochrome P450 isoform 2E1; GCLC: Glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; GST: Glutathione-S-transferase; HO-1: Heme-oxygenase 1; IKK: Inhibitor of IκB kinase; iNOS: Inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IL-6R: Interleukin-6 receptor; JAK: Janus kinase; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MnSOD: Manganese superoxide dismutase; MRP: Multidrug resistance protein; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κB; NQO-1: NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1; Nrf2: Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2; QO2: Rate of oxygen consumption; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; STAT3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; Thr: Thioredoxin; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; TNFR1: Tumor necrosis factor-α receptor 1; UDPGT: UDP-glucuronyl transferase.

Recently, in vivo T3 administration to rats was shown to activate hepatic nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), as evidenced by the increased cytosol-to-nuclear translocation observed[41]. Liver Nrf2 activation induced by T3 appears to be a redox-dependent process due to its abolishment by N-acetylcysteine pretreatment, which may be contributed by Nrf2 phosphorylation related to p38 activation[41]. This would represent a novel and alternate cytoprotective mechanism of T3 action against free-radical and electrophile toxicity[41], in addition to that afforded by NF-κB, STAT3 and AP-1 up-regulation[34-36] (Figure 1), considering that Nrf2 controls the expression of antioxidant components, detoxification enzymes or membrane transporters (Figure 1) and interplays with NF-κB affording anti-inflammatory responses[42].

Redox activation of NF-κB, STAT3, AP-1 and Nrf2 up-regulating transcription of protective genes represents an additional non-genomic mechanism of T3 action to those reported for different cellular processes[43], which is dependent upon the genomic pathway enhancing energy metabolism with ROS production. These observations constitute the basis for liver PC by T3, with integration of different T3-signaling inputs to achieve metabolic and redox balance (Figure 1) that are required to deal with the cytotoxic mechanisms underlying IR liver injury. Increased hepatocyte proliferation compensating for liver cells lost due to IR-induced necrosis[36] is an additional PC response due to the mitogenic action of T3, leading to direct hyperplasia[44]. In agreement with these views, IR-induced (1) drastic enhancement in liver oxidative stress status and TNF-α response; (2) loss of DNA binding capacity of NF-κB and STAT3, implying loss of cytoprotective potential; and (3) major increment in hepatic AP-1 activation, which constitutes a crucial determinant of hepatotoxicity under conditions of reduced NF-κB activation and enhanced TNF-α response, are normalized by T3 treatment[26]. Similar T3 actions involving other physiological functions have been described, including (1) NF-κB activation in lymphocytes from thyroxin-treated rats[45] or hyperthyroid patients[46] in association with higher oxidative stress status and potentiation of humoral immune response; and (2) JNK/STAT3 activation by T3 in a nutritional model of non-alcoholic steatosis in rats, with complete regression of fat accumulation[47].

n-3 LONG-CHAIN-POLYUNSATURATED FATTY ACID LIVER PRECONDITIONING

Dietary fatty acids, especially LCPUFA, are essential for growth and development in mammals including man, both n-6 and n-3 LCPUFAs being important as structural components of cellular lipids and substrates for the synthesis of physiological mediators[48]. Among the n-3 series of LCPUFAs, eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5n-3; EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6n-3; DHA), produced from α-linolenic acid (C18:3n-3), have been associated with multiple positive health effects[48,49] and proposed for the prevention of non transmissible chronic diseases[50] or against heart[51] and liver[27] IR injury. It is considered that attainment of a given n-6/n-3 ratio is crucial for prevention and treatment of several diseases, as a potential sensor for the activation of mechanisms involved in inflammatory processes[52] such as liver IR injury[1-6].

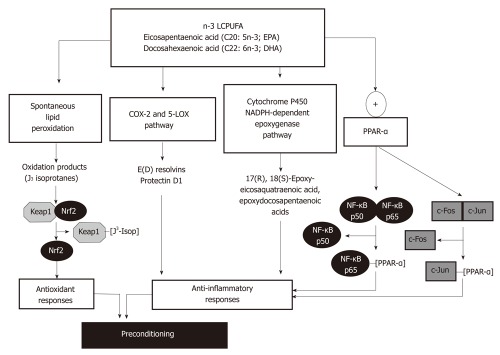

Recently, liver PC against IR injury was reported in rats subjected to fish oil (270 mg/kg EPA plus 180 mg/kg DHA) or saline (controls) administration for 7 d, prior to the 1 h ischemia-20 h reperfusion protocol[27]. In vivo n-3 LCPUFA supplementation significantly enhanced liver n-3 LCPUFA content and decreased n-6/n-3 LCPUFA ratios, with prevention of IR-induced liver injury, suppression of oxidative stress, recovery of pro-inflammatory cytokine homeostasis, and NF-κB functionality lost during IR[27]. Several molecular mechanisms can be invoked to explain liver PC by n-3 LCPUFA, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid -induced liver preconditioning is associated with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses triggered by oxidative products and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor -α activation. n-3 LCPUFA: n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid; COX-2: Cyclo-oxygenase 2; Keap1: Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; 5-LOX: 5-lipoxygenase; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κB; Nrf2: Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2; PPAR-α: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α.

Considering the high susceptibility of n-3 LCPUFAs to free-radical attack with further decomposition[53], these fatty acids readily undergo in vitro non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation with formation of cyclopentenone-containing J-ring isoprostanes (J3-isoprostanes)[54]. Gao et al[54] reported that J3-isoprostanes from EPA and DHA oxidation react with sulfhydryl groups in recombinant Keap1, a Cul-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase (Cul3)-Ring box 1 complex responsible for Nrf2 ubiquitination and degradation[55]. This interaction alters Keap1 structure, leading to loss of binding to Cul3, Nrf2 stabilization and nuclear translocation, with expression of the antioxidant enzymes heme-oxygenase-1 and glutamate cysteine ligase, as assessed in cultured HepG2 cells[54] (Figure 2). In agreement with these findings, in vivo EPA supplementation in mice was shown to up-regulate the expression of other Nrf2-dependent antioxidant proteins, namely, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, glutathione-S-transferase and catalase, with significant increases in liver glutathione content and diminution in lipid peroxidation rate[56].

Both EPA and DHA have been reported as effective anti-inflammatory and tissue protective mediators[48-50], effects that may underlie different mechanisms of action (Figure 2). These include various aspects of eicosanoid metabolism generating n-3 LCPUFA-derived mediators produced in the resolution phase following acute inflammation. EPA and DHA can be metabolized by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) to generate E-series and D-series of resolvins in vivo and in vitro, respectively (Figure 2), which exhibit anti-inflammatory effects compared with those derived from arachidonic acid[57]. DHA can also be metabolized by 5-LOX to produce protectins, protectin D1 being the most potent anti-inflammatory isomer[58] (Figure 2). Resolvins E1, E2 and protectin D1 exert their anti-inflammatory action mainly through inhibition of neutrophil infiltration in target tissues[57,59]. In the case of resolving E1, its binding to G-protein-coupled receptors chemokine-like receptor-1 and leukotriene B4 receptor attenuates the pro-inflammatory effects of NF-κB and leukotriene B4 signaling, respectively[60]. Although the influence of resolvins and protectins has not been evaluated in IR liver injury, mouse kidney subjected to bilateral IR leads to endogenous mobilization and higher blood levels of DHA, with enhanced production of D-series of resolvins and protectins[61]. Moreover, pretreatment with exogenous resolvins was able to protect from IR kidney injury[61]. Interestingly, in vivo DHA supplementation is protective against liver necroinflammatory injury in mice subjected to carbon tetrachloride intoxication, a condition enhancing hepatic formation of the DHA-derived metabolites 17S-hydroxy-DHA (17S-HDHA) and protectin D1[62]. These findings and the protective effect of DHA and 17S-HDHA against in vitro hydrogen peroxide toxicity in hepatocytes establish a significant protective role of n-3 LCPUFA supplementation in well-known animal models of liver injury, which amplifies formation of DHA-derived anti-inflammatory lipid mediators in the liver[62] (Figure 2). In addition to EPA and DHA metabolism by the COX2/5-LOX pathway, these fatty acids may undergo oxygenation by cytochrome P450 NADPH-dependent epoxygenases (Figure 2), with production of multiple epoxyeicosaquatraenoic acid and epoxydocosapentaenoic acid regioisomers, respectively[57,63], which might have anti-inflammatory effects[57]. The finding that IR elicited a net decrease in the content of n-3 LCPUFA in the liver of EPA plus DHA supplemented rats over that in non-supplemented animals[27], support the contention that in vivo n-3 LCPUFA protection may be related to utilization of the fatty acids in lipid peroxidation, COX-2/5-LOX and cytochrome P450-dependent epoxygenation pathways. However, n-3 LCPUFA β-oxidation and replacement for n-6 LCPUFA in membrane phospholipids cannot be discarded.

In addition to the above discussed mechanisms related to the anti-inflammatory responses of n-3 LCPUFA involving oxidative processes, EPA and DHA may directly alter intracellular signaling pathways associated with transcription factors peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR)-α/PPAR-γ and NF-κB/AP-1. The mechanism is based on the findings that LCPUFA, fatty acid derivatives and eicosanoids act as natural ligands for PPARs leading to their activation[64], which physically interact with both the p65 component of NF-κB and the c-Jun component of AP-1 (Figure 2), thus interfering with NF-κB and AP-1 transactivation of inflammatory genes[65]. Alternate mechanisms triggered by PPAR-α activation include: (1) enhancement of IκB-α mRNA and protein expression and its nuclear abundance, with diminution in NF-κB DNA binding activity[66]; (2) decreased IκB-α degradation, probably due to diminished phosphorylation[67]; and (3) up-regulation of antioxidant enzymes[56,68] (Figure 2) with reduction of the oxidative stress status, leading to loss of NF-κB activation and inflammatory cytokine production[68]. n-3 LCPUFA-induced re-establishment of inflammatory cytokine homeostasis under IR conditions[27,69] is accompanied by improvement of hepatic microcirculation, as a contributory factor protecting the liver against IR injury[70,71]. Although the relevance of n-3 LCPUFA supplementation in conditions underlying IR liver injury in humans has not been evaluated, several clinical studies have reported that supplementation with fish oil, seal oil or purified n-3 LCPUFA reduces hepatic lipid content in obese non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients[72-76], exhibiting substantial depletion of n-3 LCPUFA content[77]. In addition, n-3 LCPUFA administration improved circulating liver function markers[72-76], serum triacylglycerol (TAG)[73,74] and tumor necrosis factor-α[73] levels, and hepatic microcirculatory function[72].

IRON LIVER PRECONDITIONING

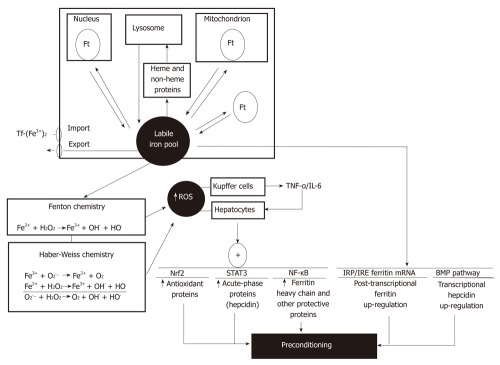

Iron is an essential micronutrient and bio-catalyst of oxidation-reduction reactions that are related to its chemistry promoting electron exchange under aerobic conditions, being crucial for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and other processes requiring enzymes/proteins with iron as a cofactor[78,79]. At the different cell compartments, iron is bound to low-molecular-weight molecules, giving a steady-state concentration of labile iron within the cell. This labile iron pool corresponds to a low-molecular-weight pool of weakly chelated iron that readily passes through the cell, representing a minor fraction of total cellular iron (3%-5%)[79]. The cellular labile iron pool is in equilibrium with (1) iron taken from the diet, delivered into bloodstream, and incorporated into cells through transferring-receptors; (2) iron export; (3) iron reversibly incorporated into heme and non-heme proteins; and (4) iron stored in ferritin, which constitutes a major and safe fraction of the iron that entered into the cell (Figure 3)[79].

Figure 3.

Redox signaling in iron (Fe)-induced liver preconditioning is elicited by the cellular labile Fe pool triggering nuclear factor-erythroid 2, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, and nuclear factor-κB activation and iron-regulatory protein / iron-responsive element post-transcriptional up-regulation with antioxidant and acute-phase responses. BMP: Bone morphogenetic protein; Ft: Ferritin; H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide; HO•: hydroxyl radical; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IRE: Iron-responsive element; IRP: Iron-regulatory protein; Nrf2: Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; STAT3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; O2−: Superoxide radical; Tf: Transferring; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

The intracellular labile iron pool has been associated with physiological, pharmacological and toxicological iron functions. Iron is able to catalyze the conversion of by-products of respiration [superoxide radical (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)] into hydroxyl radical (HO•) via the Fenton reaction or the Fe2+-assisted Haber-Weiss reaction (Figure 3)[79], thus enhancing the oxidative stress status of the cell. Rats subjected to a sub-chronic iron administration protocol (six doses of 50 mg iron-dextran/kg, ip every second day during 10 d) showed significant enhancement in total iron and in the labile iron pool of the liver, with consequent up-regulation of ferritin content, thus establishing a transient oxidative stress condition without development of hepatotoxicity[28]. Under these conditions, a significant protection was afforded by iron administration against liver IR injury, as evidenced by diminution in serum transaminase levels and normal liver architecture observed in iron supplemented animals subjected to IR compared to non-supplemented rats[28]. Iron liver preconditioning against IR could be due to cellular iron metabolism over the 72 h time-period between in vivo iron administration and the settlement of IR in vitro, with consequent ferritin up-regulation sequestering large amounts of administered iron to avoid liver injury, and expansion of the labile iron pool increasing the oxidative stress status that limits the further pro-oxidant challenge of IR. In addition, suppression of the TNF-α response and reversion of the changes in signal transduction and gene expression induced by IR were achieved by in vivo iron administration, with recovery of NF-κB activation and NF-κB-related expression of haptoglobin lost during IR (Figure 3)[28]. Haptoglobin is an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant acute-phase protein participating in the acute-phase response of the liver, a reaction restoring homeostasis by contributing to defensive and adaptive capabilities[80].

From the mechanistic viewpoint, development of transient oxidative stress in the liver of iron supplemented animals may be related to stimulation of different processes in Kupffer cells and hepatocytes. In vivo iron overload alters the functional status of Kupffer cells by increasing the respiratory burst activity without modifying phagocytosis, an effect that is probably related to O2 equivalents used by NADPH oxidase to produce O2•− and H2O2, which may be further subjected to Fenton/Haber-Weiss reactions (Figure 3)[81]. Promotion of biomolecules oxidation and activation of nitric oxide synthase[82] may also contribute to this effect of iron. Iron-induced respiratory burst of Kupffer cells with enhanced ROS production[81] may have a role in NF-κB signaling, as shown by the activation of IKK and NF-κB DNA binding, leading to enhanced TNF-α promoter activity and TNF-α release from cultured Kupffer cells[83] (Figure 3). As proposed for T3 liver preconditioning (Figure 1), TNF-α released from Kupffer cells may trigger protective signaling cascades in hepatocytes, thus achieving protection against IR liver injury. Interestingly, ferritin heavy chain was identified as an essential mediator of the antioxidant and protective actions of NF-κB, as assessed in cultured NIN-3T3 cells[84]. This protein is induced downstream of NF-κB, providing a transcriptional regulatory mechanism for ferritin induction through iron-mediated ROS generation[85] (Figure 3), which represents a potential approach for anti-inflammatory therapy[84]. Up-regulation of ferritin expression by iron is also under post-transcriptional regulation, a mechanism involving the interaction of iron regulatory proteins with the iron-responsive elements in ferritin mRNA, to enhance ferritin synthesis and concentrate excess iron[84,86], avoiding cytotoxicity (Figure 3). Besides, iron overload up-regulates hepcidin expression, an acute-phase protein produced by hepatocytes that controls the dietary absorption, storage and tissue distribution of iron, which exhibits a significant correlation with serum ferritin levels[87]. The mechanism of hepcidin action involves internalization and degradation of ferroportin, a hepcidin-receptor and iron channel, that diminishes intestinal iron absorption, iron mobilization from hepatocytes, and iron recycling by macrophages, leading to iron entrapment in ferritin at enterocyte, macrophage and hepatocyte levels[87]. Although regulation of liver hepcidin transcription by iron involving the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway is not completely understood[87], IL-6/STAT3 signaling is a key effector of hepcidin expression during inflammatory conditions[88], a redox-sensitive pathway controlling the expression of several other acute-phase proteins (Figure 3). In addition to NF-κB and STAT3, liver Nrf2 signaling may also contribute to iron-induced preconditioning, considering (1) the enhancement in the expression of liver Nrf2 protein and catalase, glutathione-S-transferase and heme-oxygenase-1 mRNA in mice subjected to iron overloading[89]; and (2) the significant diminution in hepatic glutathione levels and in glutamate cysteine ligase activity observed in Nrf2(-/-) mice treated with ferric nitrilotriacetate over wild-type animals[90] (Figure 3).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

T3, n-3 LCPUFA and iron can be considered as hormetic agents[91,92], which are defined as compounds inducing a dose-response phenomenon characterized by biologically beneficial effects in the low-concentration (dose) range (organ preconditioning)[26-28] and harmful responses at high concentrations (doses) or after prolonged exposure (thyrotoxicosis[93], gastrointestinal upset/increase bleeding time[48] and hemochromatosis[94], respectively). Organ preconditioning by these hormetic agents is not restricted to the liver[26-28], considering that (1) thyroid hormone-induced preconditioning against IR injury is also observed in the heart[95,96], with a pattern of protection comparable to that of ischemic preconditioning[97]; (2) beneficial effects of n-3 LCPUFA have been demonstrated in rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, coronary artery disease, asthma and sepsis, conditions with inflammation as a key component of their pathology[48], in addition to neuroinflammation in all major central nervous system diseases[98]; and (3) protective effects of iron are reported in cardiomyocytes and heart[99-101], oligodendroglia cells[102] and neurones[103]. T3, n-3 LCPUFA or iron liver preconditioning are suitable to be introduced in the clinical setting, considering that these hormetins are known to be well tolerated in the treatment of hypothyroidism[104], non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[72-76] and other diseases[48], or anemia[105,106], respectively. Interestingly, there is evidence to conclude that n-3 LCPUFAs potentiate the effects of certain drugs, thereby allowing a reduction of their required dose, thus avoiding adverse effects[48]. In agreement with this view, combined n-3 LCPUFA (300 mg/kg for 3 consecutive days) plus T3 (0.05 mg/kg) administration prevented rat liver IR injury, whereas separate protocols lack protection[107], when compared with the preconditioning action afforded by separate n-3 LCPUFA (300 mg/kg for 7 consecutive days)[27] or T3 (0.1 mg/kg)[26]. Data discussed in this article warrants further experimental and clinical research in the future, to support the incorporation of T3, n-3 LCPUFA and iron preconditioning strategies or their combinations in human liver resections and in human liver transplantation using reduced-size grafts from living donors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Drs. I Castillo, P Romanque, S Uribe-Echvarría, M Uribe, MT Vial, F Venegas, M Villarreal, D Núñez, M Chandía, R Valenzuela, P Varela, M Galleano and S Puntarulo for valuable discussion, and whose contributions are cited in the article.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants No. 1110006 to Fernández V, No. 1110043 to Tapia G and No. 1090020 to Videla LA from FONDECYT, Chile

Peer reviewer: Dr. Amedeo Lonardo, Department of Internal Medicine, Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Via Giardini, Modena 41100, Italy

S- Editor Wu X L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Wu X

References

- 1.Videla LA. Oxidative stress signaling underlying liver disease and hepatoprotective mechanisms. World J Hepatol. 2009;1:72–78. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v1.i1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teoh NC, Farrell GC. Hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury: pathogenic mechanisms and basis for hepatoprotection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:891–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaeschke H. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G15–G26. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00342.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selzner N, Rudiger H, Graf R, Clavien PA. Protective strategies against ischemic injury of the liver. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:917–936. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banga NR, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Graham A, Al-Mukhtar A, White SA, Prasad KR. Ischaemic preconditioning in transplantation and major resection of the liver. Br J Surg. 2005;92:528–538. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Rougemont O, Lehmann K, Clavien PA. Preconditioning, organ preservation, and postconditioning to prevent ischemia-reperfusion injury to the liver. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1172–1182. doi: 10.1002/lt.21876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casillas-Ramírez A, Mosbah IB, Ramalho F, Roselló-Catafau J, Peralta C. Past and future approaches to ischemia-reperfusion lesion associated with liver transplantation. Life Sci. 2006;79:1881–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das M, Das DK. Molecular mechanism of preconditioning. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:199–203. doi: 10.1002/iub.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahde R, Spiegel HU. Hepatic ischaemia-reperfusion injury from bench to bedside. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1461–1475. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terajima H, Enders G, Thiaener A, Hammer C, Kondo T, Thiery J, Yamamoto Y, Yamaoka Y, Messmer K. Impact of hyperthermic preconditioning on postischemic hepatic microcirculatory disturbances in an isolated perfusion model of the rat liver. Hepatology. 2000;31:407–415. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu SY, Chiu JH, Yang SD, Yu HY, Hsieh CC, Chen PJ, Lui WY, Wu CW. Preconditioned hyperbaric oxygenation protects the liver against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J Surg Res. 2005;128:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rüdiger HA, Graf R, Clavien PA. Sub-lethal oxidative stress triggers the protective effects of ischemic preconditioning in the mouse liver. J Hepatol. 2003;39:972–977. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito K, Ozasa H, Sanada K, Horikawa S. Doxorubicin preconditioning: a protection against rat hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Hepatology. 2000;31:416–419. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ajamieh HH, Menéndez S, Martínez-Sánchez G, Candelario-Jalil E, Re L, Giuliani A, Fernández OS. Effects of ozone oxidative preconditioning on nitric oxide generation and cellular redox balance in a rat model of hepatic ischaemia-reperfusion. Liver Int. 2004;24:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romanque P, Díaz A, Tapia G, Uribe-Echevarría S, Videla LA, Fernandez V. Delayed ischemic preconditioning protects against liver ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:1569–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clavien PA, Selzner M, Rüdiger HA, Graf R, Kadry Z, Rousson V, Jochum W. A prospective randomized study in 100 consecutive patients undergoing major liver resection with versus without ischemic preconditioning. Ann Surg. 2003;238:843–50; discussion 851-2. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098620.27623.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyrniotis V, Theodoraki K, Arkadopoulos N, Fragulidis G, Condi-Pafiti A, Plemenou-Fragou M, Voros D, Vassiliou J, Dimakakos P. Ischemic preconditioning versus intermittent vascular occlusion in liver resections performed under selective vascular exclusion: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg. 2006;192:669–674. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heizmann O, Loehe F, Volk A, Schauer RJ. Ischemic preconditioning improves postoperative outcome after liver resections: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Med Res. 2008;13:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Totsuka E, Fung JJ, Urakami A, Moras N, Ishii T, Takahashi K, Narumi S, Hakamada K, Sasaki M. Influence of donor cardiopulmonary arrest in human liver transplantation: possible role of ischemic preconditioning. Hepatology. 2000;31:577–580. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrier A, Olaya N, Chiappini F, Roser F, Scatton O, Artus C, Franc B, Dudoit S, Flahault A, Debuire B, et al. Ischemic preconditioning modulates the expression of several genes, leading to the overproduction of IL-1Ra, iNOS, and Bcl-2 in a human model of liver ischemia-reperfusion. FASEB J. 2005;19:1617–1626. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3445com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amador A, Grande L, Martí J, Deulofeu R, Miquel R, Solá A, Rodriguez-Laiz G, Ferrer J, Fondevila C, Charco R, et al. Ischemic pre-conditioning in deceased donor liver transplantation: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2180–2189. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koneru B, Fisher A, He Y, Klein KM, Skurnick J, Wilson DJ, de la Torre AN, Merchant A, Arora R, Samanta AK. Ischemic preconditioning in deceased donor liver transplantation: a prospective randomized clinical trial of safety and efficacy. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:196–202. doi: 10.1002/lt.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azoulay D, Lucidi V, Andreani P, Maggi U, Sebagh M, Ichai P, Lemoine A, Adam R, Castaing D. Ischemic preconditioning for major liver resection under vascular exclusion of the liver preserving the caval flow: a randomized prospective study. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahbari NN, Wente MN, Schemmer P, Diener MK, Hoffmann K, Motschall E, Schmidt J, Weitz J, Büchler MW. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of portal triad clamping on outcome after hepatic resection. Br J Surg. 2008;95:424–432. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández V, Castillo I, Tapia G, Romanque P, Uribe-Echevarría S, Uribe M, Cartier-Ugarte D, Santander G, Vial MT, Videla LA. Thyroid hormone preconditioning: protection against ischemia-reperfusion liver injury in the rat. Hepatology. 2007;45:170–177. doi: 10.1002/hep.21476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zúñiga J, Venegas F, Villarreal M, Núñez D, Chandía M, Valenzuela R, Tapia G, Varela P, Videla LA, Fernández V. Protection against in vivo liver ischemia-reperfusion injury by n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the rat. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:854–863. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.485995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galleano M, Tapia G, Puntarulo S, Varela P, Videla LA, Fernández V. Liver preconditioning induced by iron in a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion. Life Sci. 2011;89:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz HL, Oppenheimer JH. Physiologic and biochemical actions of thyroid hormone. Pharmacol Ther B. 1978;3:349–376. doi: 10.1016/s0306-039x(78)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernández V, Videla LA. Kupffer cell-dependent signaling in thyroid hormone calorigenesis: possible applications for liver preconditioning. Curr Signal Trans Ther. 2009;4:144–151. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernández V, Videla LA. Influence of hyperthyroidism on superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide production by rat liver submitochondrial particles. Free Radic Res Commun. 1993;18:329–335. doi: 10.3109/10715769309147500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venditti P, De Rosa R, Di Meo S. Effect of thyroid state on H2O2 production by rat liver mitochondria. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;205:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukamoto H, Lin M. The role of Kupffer cells in liver injury. In: Wisse E, Knook DL, Balabaud C, editors. Cells of the Hepatic Sinusoid. Leiden, The Netherlands: Kupffer Cell Foundation; 2008. pp. 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernández V, Tapia G, Varela P, Castillo I, Mora C, Moya F, Orellana M, Videla LA. Redox up-regulated expression of rat liver manganese superoxide dismutase and Bcl-2 by thyroid hormone is associated with inhibitor of kappaB-alpha phosphorylation and nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J Endocrinol. 2005;186:539–547. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tapia G, Fernández V, Pino C, Ardiles R, Videla LA. The acute-phase response of the liver in relation to thyroid hormone-induced redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1628–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernández V, Reyes S, Bravo S, Sepúlveda R, Romanque P, Santander G, Castillo I, Varela P, Tapia G, Videla LA. Involvement of Kupffer cell-dependent signaling in T3-induced hepatocyte proliferation in vivo. Biol Chem. 2007;388:831–837. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirano T, Ishihara K, Hibi M. Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene. 2000;19:2548–2556. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leedman PJ, Stein AR, Chin WW, Rogers JT. Thyroid hormone modulates the interaction between iron regulatory proteins and the ferritin mRNA iron-responsive element. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12017–12023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanni A, Moreno M, Lombardi A, Goglia F. Thyroid hormone and uncoupling proteins. FEBS Lett. 2003;543:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goglia F, Skulachev VP. A function for novel uncoupling proteins: antioxidant defense of mitochondrial matrix by translocating fatty acid peroxides from the inner to the outer membrane leaflet. FASEB J. 2003;17:1585–1591. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0159hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romanque P, Cornejo P, Valdés S, Videla LA. Thyroid hormone administration induces rat liver Nrf2 activation: suppression by N-acetylcysteine pretreatment. Thyroid. 2011;21:655–662. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh S, Vrishni S, Singh BK, Rahman I, Kakkar P. Nrf2-ARE stress response mechanism: a control point in oxidative stress-mediated dysfunctions and chronic inflammatory diseases. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:1267–1288. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.507670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis PJ, Leonard JL, Davis FB. Mechanisms of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Columbano A, Shinozuka H. Liver regeneration versus direct hyperplasia. FASEB J. 1996;10:1118–1128. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.10.8751714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vinayagamoorthi R, Koner BC, Kavitha S, Nandakumar DN, Padma Priya P, Goswami K. Potentiation of humoral immune response and activation of NF-kappaB pathway in lymphocytes in experimentally induced hyperthyroid rats. Cell Immunol. 2005;238:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nandakumar DN, Koner BC, Vinayagamoorthi R, Nanda N, Negi VS, Goswami K, Bobby Z, Hamide A. Activation of NF-kappaB in lymphocytes and increase in serum immunoglobulin in hyperthyroidism: possible role of oxidative stress. Immunobiology. 2008;213:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perra A, Simbula G, Simbula M, Pibiri M, Kowalik MA, Sulas P, Cocco MT, Ledda-Columbano GM, Columbano A. Thyroid hormone (T3) and TRbeta agonist GC-1 inhibit/reverse nonalcoholic fatty liver in rats. FASEB J. 2008;22:2981–2989. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fetterman JW, Zdanowicz MM. Therapeutic potential of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:1169–1179. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferguson LR, Smith BG, James BJ. Combining nutrition, food science and engineering in developing solutions to Inflammatory bowel diseases--omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids as an example. Food Funct. 2010;1:60–72. doi: 10.1039/c0fo00057d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim W, McMurray DN, Chapkin RS. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids--physiological relevance of dose. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;82:155–158. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodrigo R, Cereceda M, Castillo R, Asenjo R, Zamorano J, Araya J, Castillo-Koch R, Espinoza J, Larraín E. Prevention of atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: basis for a novel therapeutic strategy based on non-hypoxic myocardial preconditioning. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:104–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:674–688. doi: 10.3181/0711-MR-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sevanian A, Hochstein P. Mechanisms and consequences of lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Annu Rev Nutr. 1985;5:365–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.05.070185.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao L, Wang J, Sekhar KR, Yin H, Yared NF, Schneider SN, Sasi S, Dalton TP, Anderson ME, Chan JY, et al. Novel n-3 fatty acid oxidation products activate Nrf2 by destabilizing the association between Keap1 and Cullin3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2529–2537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang DD. Mechanistic studies of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38:769–789. doi: 10.1080/03602530600971974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Demoz A, Willumsen N, Berge RK. Eicosapentaenoic acid at hypotriglyceridemic dose enhances the hepatic antioxidant defense in mice. Lipids. 1992;27:968–971. doi: 10.1007/BF02535573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Roos B, Mavrommatis Y, Brouwer IA. Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: new insights into mechanisms relating to inflammation and coronary heart disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:413–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong S, Gronert K, Devchand PR, Moussignac RL, Serhan CN. Novel docosatrienes and 17S-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells. Autacoids in anti-inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14677–14687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arita M, Ohira T, Sun YP, Elangovan S, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 selectively interacts with leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and ChemR23 to regulate inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178:3912–3917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duffield JS, Hong S, Vaidya VS, Lu Y, Fredman G, Serhan CN, Bonventre JV. Resolvin D series and protectin D1 mitigate acute kidney injury. J Immunol. 2006;177:5902–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.González-Périz A, Planagumà A, Gronert K, Miquel R, López-Parra M, Titos E, Horrillo R, Ferré N, Deulofeu R, Arroyo V, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) blunts liver injury by conversion to protective lipid mediators: protectin D1 and 17S-hydroxy-DHA. FASEB J. 2006;20:2537–2539. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6250fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ye D, Zhang D, Oltman C, Dellsperger K, Lee HC, VanRollins M. Cytochrome p-450 epoxygenase metabolites of docosahexaenoate potently dilate coronary arterioles by activating large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:768–776. doi: 10.1124/jpet.303.2.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forman BM, Chen J, Evans RM. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4312–4317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delerive P, De Bosscher K, Besnard S, Vanden Berghe W, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Fruchart JC, Tedgui A, Haegeman G, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha negatively regulates the vascular inflammatory gene response by negative cross-talk with transcription factors NF-kappaB and AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32048–32054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delerive P, Gervois P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Induction of IkappaBalpha expression as a mechanism contributing to the anti-inflammatory activities of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activators. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36703–36707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Calder PC. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Poynter ME, Daynes RA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activation modulates cellular redox status, represses nuclear factor-kappaB signaling, and reduces inflammatory cytokine production in aging. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32833–32841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iwasaki W, Kume M, Kudo K, Uchinami H, Kikuchi I, Nakagawa Y, Yoshioka M, Yamamoto Y. Changes in the fatty acid composition of the liver with the administration of N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the effects on warm ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat liver. Shock. 2010;33:306–314. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181b2ffd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhong Z, Thurman RG. A fish oil diet minimizes hepatic reperfusion injury in the low-flow, reflow liver perfusion model. Hepatology. 1995;22:929–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.El-Badry AM, Moritz W, Contaldo C, Tian Y, Graf R, Clavien PA. Prevention of reperfusion injury and microcirculatory failure in macrosteatotic mouse liver by omega-3 fatty acids. Hepatology. 2007;45:855–863. doi: 10.1002/hep.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Capanni M, Calella F, Biagini MR, Genise S, Raimondi L, Bedogni G, Svegliati-Baroni G, Sofi F, Milani S, Abbate R, et al. Prolonged n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation ameliorates hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1143–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spadaro L, Magliocco O, Spampinato D, Piro S, Oliveri C, Alagona C, Papa G, Rabuazzo AM, Purrello F. Effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu FS, Liu S, Chen XM, Huang ZG, Zhang DW. Effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from seal oils on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with hyperlipidemia. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6395–6400. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hatzitolios A, Savopoulos C, Lazaraki G, Sidiropoulos I, Haritanti P, Lefkopoulos A, Karagiannopoulou G, Tzioufa V, Dimitrios K. Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids, atorvastatin and orlistat in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with dyslipidemia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanaka N, Sano K, Horiuchi A, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Aoyama T. Highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid treatment improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:413–418. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815591aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Araya J, Rodrigo R, Videla LA, Thielemann L, Orellana M, Pettinelli P, Poniachik J. Increase in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid n - 6/n - 3 ratio in relation to hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:635–643. doi: 10.1042/CS20030326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pierre JL, Fontecave M, Crichton RR. Chemistry for an essential biological process: the reduction of ferric iron. Biometals. 2002;15:341–346. doi: 10.1023/a:1020259021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Puntarulo S, Galleano M. Forms of iron binding in the cells and the chemical features of chelation therapy. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9:1136–1146. doi: 10.2174/138955709788922674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gruys E, Toussaint MJ, Niewold TA, Koopmans SJ. Acute phase reaction and acute phase proteins. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2005;6:1045–1056. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2005.B1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Videla LA, Fernández V, Tapia G, Varela P. Oxidative stress-mediated hepatotoxicity of iron and copper: role of Kupffer cells. Biometals. 2003;16:103–111. doi: 10.1023/a:1020707811707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cornejo P, Tapia G, Puntarulo S, Galleano M, Videla LA, Fernández V. Iron-induced changes in nitric oxide and superoxide radical generation in rat liver after lindane or thyroid hormone treatment. Toxicol Lett. 2001;119:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(00)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.She H, Xiong S, Lin M, Zandi E, Giulivi C, Tsukamoto H. Iron activates NF-kappaB in Kupffer cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G719–G726. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00108.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pham CG, Bubici C, Zazzeroni F, Papa S, Jones J, Alvarez K, Jayawardena S, De Smaele E, Cong R, Beaumont C, et al. Ferritin heavy chain upregulation by NF-kappaB inhibits TNFalpha-induced apoptosis by suppressing reactive oxygen species. Cell. 2004;119:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Templeton DM, Liu Y. Genetic regulation of cell function in response to iron overload or chelation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1619:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00497-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Theil EC, Eisenstein RS. Combinatorial mRNA regulation: iron regulatory proteins and iso-iron-responsive elements (Iso-IREs) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40659–40662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ganz T. Hepcidin and iron regulation, 10 years later. Blood. 2011;117:4425–4433. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-258467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Verga Falzacappa MV, Vujic Spasic M, Kessler R, Stolte J, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU. STAT3 mediates hepatic hepcidin expression and its inflammatory stimulation. Blood. 2007;109:353–358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moriya K, Miyoshi H, Shinzawa S, Tsutsumi T, Fujie H, Goto K, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Koike K. Hepatitis C virus core protein compromises iron-induced activation of antioxidants in mice and HepG2 cells. J Med Virol. 2010;82:776–792. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kanki K, Umemura T, Kitamura Y, Ishii Y, Kuroiwa Y, Kodama Y, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Nishikawa A, Hirose M. A possible role of nrf2 in prevention of renal oxidative damage by ferric nitrilotriacetate. Toxicol Pathol. 2008;36:353–361. doi: 10.1177/0192623307311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Calabrese EJ. Converging concepts: adaptive response, preconditioning, and the Yerkes-Dodson Law are manifestations of hormesis. Ageing Res Rev. 2008;7:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Videla LA. Hormetic responses of thyroid hormone calorigenesis in the liver: Association with oxidative stress. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:460–466. doi: 10.1002/iub.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Braverman LE, Utiger RD. Introduction to thyrotoxicosis. In: Braverman LA, Utiger RD, editors. Werner and Ingbar,s The Thyroid. A Fundamental and Clinical Text, New York: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 522–524. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bacon BR, Britton RS. Hepatic injury in chronic iron overload. Role of lipid peroxidation. Chem Biol Interact. 1989;70:183–226. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Buser PT, Wikman-Coffelt J, Wu ST, Derugin N, Parmley WW, Higgins CB. Postischemic recovery of mechanical performance and energy metabolism in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy. A 31P-MRS study. Circ Res. 1990;66:735–746. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.3.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pantos C, Mourouzis I, Cokkinos DV. Thyroid hormone as a therapeutic option for treating ischaemic heart disease: from early reperfusion to late remodelling. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010;52:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pantos CI, Malliopoulou VA, Mourouzis IS, Karamanoli EP, Paizis IA, Steimberg N, Varonos DD, Cokkinos DV. Long-term thyroxine administration protects the heart in a pattern similar to ischemic preconditioning. Thyroid. 2002;12:325–329. doi: 10.1089/10507250252949469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA, Farooqui T. Modulation of inflammation in brain: a matter of fat. J Neurochem. 2007;101:577–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Munoz JP, Chiong M, García L, Troncoso R, Toro B, Pedrozo Z, Diaz-Elizondo J, Salas D, Parra V, Núñez MT, et al. Iron induces protection and necrosis in cultured cardiomyocytes: Role of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chevion M, Leibowitz S, Aye NN, Novogrodsky O, Singer A, Avizemer O, Bulvik B, Konijn AM, Berenshtein E. Heart protection by ischemic preconditioning: a novel pathway initiated by iron and mediated by ferritin. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:839–845. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Metzler B, Jehle J, Theurl I, Ludwiczek S, Obrist P, Pachinger O, Weiss G. Short term protective effects of iron in a murine model of ischemia/reperfusion. Biometals. 2007;20:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9034-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brand A, Schonfeld E, Isharel I, Yavin E. Docosahexaenoic acid-dependent iron accumulation in oligodendroglia cells protects from hydrogen peroxide-induced damage. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1325–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hidalgo C, Núñez MT. Calcium, iron and neuronal function. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:280–285. doi: 10.1080/15216540701222906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brent GA, Larsen PR. Treatment of hypothyroidism. In: Braverman LA, Utiger RD, editors. Werner and Ingbar,s The Thyroid. A Fundamental and Clinical Text, New York: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 883–887. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Silverstein SB, Rodgers GM. Parenteral iron therapy options. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:74–78. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bayraktar UD, Bayraktar S. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia associated with gastrointestinal tract diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2720–2725. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mardones M, Valenzuela R, Romanque P, Covarrubias N, Anghileri F, Fernández V, Videla LA, Tapia G. Prevention of liver ischemia reperfusion injury by a combined thyroid hormone and fish oil protocol. J Nutr Biochem. 2011:[Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]