Abstract

Drug-drug interactions (DDIs) can occur when two drugs interact with the same gene product. Most available information about gene-drug relationships is contained within the scientific literature, but is dispersed over a large number of publications, with thousands of new publications added each month. In this setting, automated text mining is an attractive solution for identifying gene-drug relationships and aggregating them to predict novel DDIs. In previous work, we have shown that gene-drug interactions can be extracted from Medline abstracts with high fidelity - we extract not only the genes and drugs, but also the type of relationship expressed in individual sentences (e.g. metabolize, inhibit, activate and many others). We normalize these relationships and map them to a standardized ontology. In this work, we hypothesize that we can combine these normalized gene-drug relationships, drawn from a very broad and diverse literature, to infer DDIs. Using a training set of established DDIs, we have trained a random forest classifier to score potential DDIs based on the features of the normalized assertions extracted from the literature that relate two drugs to a gene product. The classifier recognizes the combinations of relationships, drugs and genes that are most associated with the gold standard DDIs, correctly identifying 79.8% of assertions relating interacting drug pairs and 78.9% of assertions relating noninteracting drug pairs. Most significantly, because our text processing method captures the semantics of individual gene-drug relationships, we can construct mechanistic pharmacological explanations for the newly-proposed DDIs. We show how our classifier can be used to explain known DDIs and to uncover new DDIs that have not yet been reported.

1. Introduction

Americans are living longer than ever before, and with that increased age comes a greater reliance on pharmaceuticals. For example, recent estimates by the Kaiser Family Foundation indicate that the average 70-year-old American fills over 30 prescriptions per year.1 The chance of an adverse drug reaction increases exponentially as each new drug is added to an individual’s regime. Because clinical trials for new drugs do not typically test for drug-drug interactions (DDI) directly, serious DDIs are often not discovered until a drug is already on the market. In addition, a patient who is unaware that a symptom he experiences is due to a DDI may attribute it to other factors. Many DDIs, therefore, probably go unreported.

Biologically, many DDIs are the result of conflicting or synergistic interactions between a pair of drugs and similar genes or molecular pathways within the human body.2,3 Therefore,what we observe as drug-drug interactions often take the form of drug-gene-drug interactions. Unfortunately, while lists of known DDIs are widely available and commonly-used in clinical practice, drug-gene interactions are not as widely known. In addition, genes and drugs can interact in a variety of ways, and it is unclear which interaction types are most predictive of a drug’s tendency to interact with other drugs. Furthermore, no complete databases exist that concisely describe the exact mechanisms by which drugs and genes interact; most of these interactions are only described in papers buried deep within the scientific literature.

In this environment, text mining presents a solution to the problem of uncovering novel DDIs.4-6 Our work extends a growing body of research that has sought to classify DDIs and better understand gene-drug relationships using text mining; for example, Tari et al7 developed a method that combined text mining and automated reasoning to extract novel DDIs. Other authors have built text-based networks of biological entities and used reasoning techniques to uncover new biologically-relevant relationships among them.8,9 Previous work from our own group10,11 has established methods for using a syntactical parser to identify and characterize drug-gene relationships. The end result was a semantic network of drug-gene relationships in which the edges consisted of several hundred interaction types and subject/object context terms normalized to concepts in an ontology. All of these approaches have sought to infer novel relationships among biological entities by combining known facts expressed in scientific text.

Our current work extends this line of research by using our semantic network - in particular, paths through the network that connect pairs of drugs - to infer the types of drug-gene relationships that can predict drug-drug interactions. An advantage of our method is the fact that it makes almost no a priori assumptions about the nature of these relationships, instead using a machine learning algorithm (a random forest) to identify the kinds of gene-drug relationships that best predict DDIs. Besides learning which textual features are most relevant for predicting DDIs, the method can also be used to predict novel DDIs and to “explain” these predictions through suggested mechanisms of interaction; this explanatory process is a built-in component of the algorithm. In this paper, we describe the main features of our algorithm, show how it can be used to predict possible mechanisms of interaction for a known DDI, and describe how it can be used in the future to predict novel DDIs.

2. Methods

2.1. Extracting Drug-Gene Interactions

This project builds on an earlier method for text mining Medline to extract drug-gene interactions.11 Briefly, that method works as follows:

Create two lexicons of terms, one for gene names and one for drug names. We used two custom lexicons. The first consisted of a set of 731 known pharmacodynamic and pharma-cokinetic genes identified by the PharmGKB database curators.12 The second consisted of 2,910 unique drug and drug-class names, also from PharmGKB. The gene lexicon also included all common synonyms for each gene; we required the drug name to be in itsgeneric form (rather than a brand name) to be included.a

Obtain a corpus of Medline article abstracts. The Helix Group at Stanford University maintains a corpus of all Medline abstracts published before 2009. The corpus contained about 17.5 million abstracts and 88 million sentences.

Retrieve all sentences in Medline that mention both a drug and a gene of interest. (For the purposes of this project, the drug and gene entities of interest will be known as seeds.) We accomplished this using the two aforementioned lexicons and running 100 search processes in parallel on Stanford’s BioX2 cluster.13

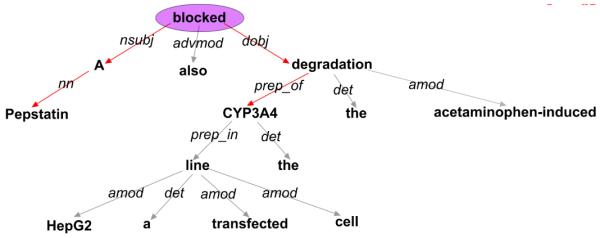

Represent sentences as dependency graphs using the Stanford Parser.14,15 The dependency graphs are rooted, oriented, and labeled graphs, where the nodes are words and the edges are dependency relations between words. If two seeds were not located in the same sentence clause, that sentence was removed from consideration. In addition, if a graph contained more than one clause and there was a clause that did not contain either seed, that clause was removed from consideration. A sample dependency graph for one Medline sentence of interest is shown in Figure 1.

Identify and normalize composite entities. A seed does not usually occur in isolation in a sentence, but as part of a larger composite entity that includes the surrounding context. For example, a gene name like CYP3A4 will usually occur as part of a larger entity, such as CYP3A4 degradation or CYP3A4 elimination. We used a previously-established algorithm10 to identify the context terms surrounding each seed and normalize them. The normalization process involved mapping context terms with similar semantics but di erent syntax, such as degradation of CYP3A4 and CYP3A4 degradation, to the same concept (Elimination) using a previously-constructed ontology.11

Extract relations between composite entities. Relations describe the nature of the interaction between the two entities in a given sentence. They take the form R(a, b), where a and b represent the locations of the two entities in the dependency graph, and R is a node that connects a and b and indicates the nature of their relationship. For a sentence to progress past this stage of the analysis, the relation connecting the gene and drug entities musthave been a verb (e.g. associated) or a nominalized verb (e.g. association).

Normalize relations. The extracted relations, like the context terms surrounding each seed, were normalized. During normalization, the raw relations were mapped onto a much smaller set of normalized relationships taken from the ontology. For example, the verbs associated and related both map to the ontological entity isAssociatedWith. In addition, less-common terms like augment were mapped to more common synonyms, like increase.

Fig. 1.

Dependency graph for the sentence “Pepstatin A also blocked the acetaminophen-induced degradation of the CYP3A4 in a transfected HepG2 cell line” (PMID: 15078344). The red arrows show the path through the graph that connects the seeds Pepstatin A (a drug) and CYP3A4 (a gene). Because this path contains a verb - in this case, “blocked” - this is a sentence of interest.

The overall goal of the normalization process for both composite entities and relations was to collapse statements with the same semantic meaning but di erent word choice or syntax to the same basic relationship, reducing the number of features that needed to be considered later when building the DDI classifier. When tested on a smaller set of drug-gene relationships extracted from Medline, our ontology was able to properly normalize approximately 80% of all relation types mentioned in the literature. Nonetheless, by including only those sentences where the relation could be normalized, we necessarily excluded some true facts about drug-gene relationships from our network. It is important to note that only sentences for which the relation could not be normalized were thrown out; sentences for which the context terms could not be normalized were still included - the context was simply normalized to Thing, as described further in Section 3.1.

2.2. Semantic Network

When applied to the entire Medline corpus, the relation extraction and normalization process yielded 76, 784 di erent normalized gene-drug relationships of the form shown in Figure 2. We eliminated all relationships in which the verb could not be normalized (i.e. was not one of the relations contained in the ontology), which left us with 53, 208 relationships b. We then put all relations in active voice, collapsing passive/active pairs of normalized verbs such as isMetabolizedBy and metabolizes into a single feature. This left 49, 021 normalized relations. However, many of these normalized relations were duplicates of each other because a given drug-gene relationship could be reported in similar ways many di erent times throughout the biomedical literature. We chose to eliminate duplicate paths of this nature. After collapsing the duplicate edges, we were left with 24, 155 unique edges, which we used to construct asemantic network, a subset of which is shown in Figure 3. Each edge in the semantic network had the form shown in Figure 2, but is simplified in Figure 3 for clarity.

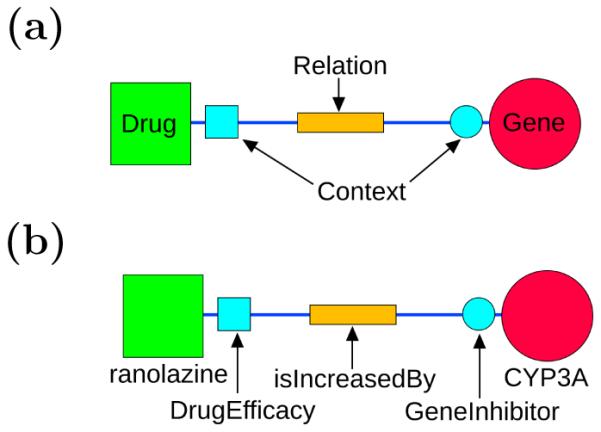

Fig. 2.

A single drug-gene edge in the semantic network. A composite entity consists of a drug or gene and its surrounding [normalized] context terms. (a) The general form of an edge. (b) A specific example.

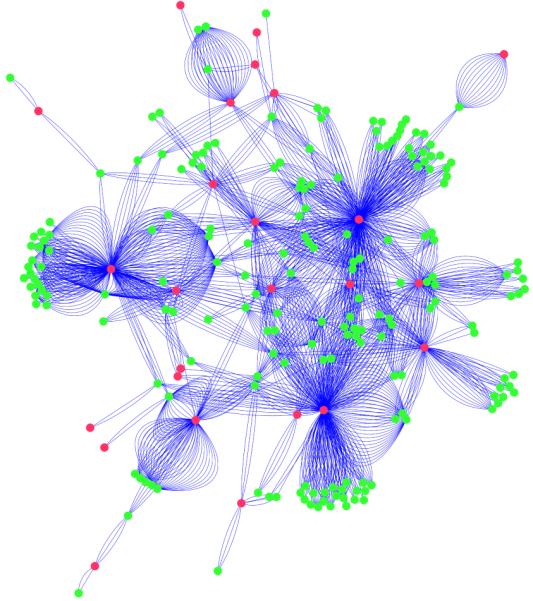

Fig. 3.

A subset of the semantic network (selected to enhance visual clarity), including only the 43 most pharmacogenomically-important genes from PharmGKB and 600 drugs that were known to interact with at least one other drug. The green nodes represent drugs and the pink nodes genes. The context terms and relations are not shown in this picture, but are present on every edge, as shown in Figure 2. Multiple edges between the same gene-drug pair in this figure represent di erent textual relationships found between that gene and drug in the literature.

2.3. Feature Extraction

The feature extraction phase of this project relied on one central assumption: that the shortest textual path linking two drugs in the network represented the simplest explanatory mechanism of their interaction (if any such mechanism existed). The set of relevant features then consisted of all the genes, relations, and context terms found on the shortest path. To find the shortest path between any two drugs D1 and D2, we performed a breadth-first search for D2, starting at D1. Breadth-first search is guaranteed to yield the optimal (shortest) path between two points on a graph.16 The shortest possible path between any two drugs in the network has the form shown in Figure 4. For the purposes of building our training set, we considered only drug pairs that had one or more shortest paths of the form in Figure 4; if the shortest path was longer than this, the drug pair was not included in the training set. We made this decision because we wanted to explore only those drug pairs for which the mechanistic explanation provided by the shortest path could be interpreted easily.

Fig. 4.

The minimum-length path between two drugs in the network. It is two edges long. The colors and symbols in this figure are identical to those in Figure 2: green squares represent drugs, and the pink circle represents a gene. The yellow rectangles represent relations, and the blue circles and squares represent context terms for genes and drugs, respectively.

By assigning each feature a numeric index, we could easily convert the lists of normalized terms found on the shortest paths into a matrix of numbers, with each row corresponding to a single path and the columns corresponding to the number of occurrences of each feature on the path. If multiple shortest paths were found, we included a separate row in our training matrix for each unique path.

2.4. Classification

The next step was to train a supervised machine learning classifier to recognize interacting drug pairs based on the textual features of their connecting paths. We randomly sampled 5000 drug pairs from a list of known interacting pairs provided by DrugBank,17 then selected 5000 additional drug pairs randomly from the drug lexicon, ensuring that none of them were on DrugBank’s list of interactionsc. For each of the 5000 pairs in our positive and negative training sets, we found all of the paths between the two drugs in the pair that took the form shown in Figure 4 and recorded the features observed along the paths. Each path between an interacting drug pair became a positive training example, and each path between a noninteracting drug pair became a negative training example.

We used a random forest,18 specifically the implementation found in the R library randomForest, to perform the final classification for all of the drug pairs in our training set. The random forest is an ensemble method in which many uncorrelated decision trees “vote” to classify data points; it outperformed both logistic regression and a support-vector machine classifier used in the early stages of this project. Each tree in the random forest uses only a subset of the features for classification, which ensures that votes from di erent trees are uncorrelated. We found that the overall classification error stabilized when approximately 200 trees were included in the forest.

2.5. Performance Evaluation

The standard metric of performance for the random forest is the out-of-bag (OOB) estimate of the error, which is similar to leave-one-out cross-validation.18 Each tree in the random forest is constructed using only about 2/3 of the available training data; the rest of the data points are referred to as the “out of bag” data for that tree. Thus it is possible to build the entire forest, then reclassify each training example using only those trees for which it was OOB. The generally-accepted rule is to use a voting cuto of 50% to classify a training point as positive; this means that for the random forest to assign the label “interacting” to a path, 50% or more of the trees in the forest had to classify that path as interacting. We used the standard OOB estimate of the error to evaluate the random forest’s performance on our training data.

One interesting feature of the random forest is that it provides a natural measure of its classification certainty for each training example - namely, the fraction of trees that voted “interact” for that example. By ranking the paths for a particular drug pair based on the number of “yes” votes each received from the random forest, we can determine which path(s)represent the most likely mechanism(s) of interaction for that pair.

3. Results

3.1. Feature Extraction

A total of 1806 entities were represented in our network: 1061 drugs, 532 genes, 172 con-text terms, and 41 relations. There were 172, 271 negative training examples (paths between 5000 noninteracting drug pairs) and 182, 534 positive training examples (paths between 5000 interacting drug pairs) in our training set, all of which had the form shown in Figure 4.

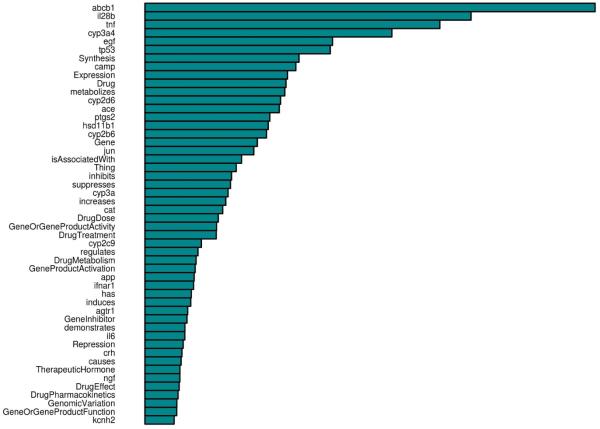

The random forest uses a permutation method to provide an estimate of which textual features were most important to the classification process; the 50 most important features are shown in Figure 5. Among the most important features are the genes ABCB1, IL28B, TNF, CYP3A4, EGF, CAMP, and CYP2D6, the context terms Synthesis, Expression, DrugDose, GeneOrGeneProductActivity, DrugTreatment, DrugMetabolism, GeneProductActivation, GeneInhibitor, Repression, and DrugE ect, and the relations metabolizes, isAssociatedWith, inhibits, suppresses, increases, regulates, and induces.

Fig. 5.

The 50 most important features to the random forest classifier, ordered according to a permutation metric;18 the numeric values of importance are not as informative as the relative sizes of the bars.

Three context terms on this list appear strange at first glance: Drug, Gene, and Thing. Context is normalized to the term Drug or Gene if the drug/gene seed is itself the subject or object of the verb or nominalized verb in the sentence, as in the example sentence CYP2C9 metabolizes warfarin. In this sentence, the gene CYP2C9 would be normalized to “CYP2C9 Gene” and the drug warfarin would be normalized to “warfarin Drug”. Context is normalized to the term Thing if the real context is some property of the drug or gene that cannot be otherwise normalized. For example, in one sentence, the authors used the term “polymorphism” incorrectly as a modifier of a drug name, referring to “polymorphisms in (drug name) drugdose … ”. Because the drug context in that sentence was polymorphisms but the seed was a drug name and not a gene name, polymorphisms was not found in the ontology among the acceptable context terms for the drug and the context was normalized to Thing. One can therefore think of Thing as a marker for cases where normalization of a context term was not possible (using the current version of the ontology), but normalization of the relation proceeded normally.

3.2. Classification and Performance Evaluation

The final contingency table for the random forest classifier is shown in Table 2. The random forest correctly assigned 281, 461 out of 354, 805 training paths (79.3%; 135, 842 non-interacting and 145, 619 interacting paths) to the correct class. It said 36, 429 paths represented interactions when the drug pair involved did not appear on the list from DrugBank (false positives), and claimed that 36, 915 paths did not represent interactions when in fact the drug pair did appear on the list from DrugBank (false negatives).

Table 2.

The raw sentences from Medline abstracts that correspond to the edges shown in Figure 6. Each path between verapamil and atorvastatin consists of two edges (i.e. two sentences).

| PMID | Normalized Relation | Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| Relationships involving f2 (thrombin) | ||

| 2611956 | verapamil Thing inhibits Gene f2 |

Ilexonin A and verapamil markedly inhibited the thrombin induced Ca2+ influx. |

| 12921859 | atorvastatin DrugEfficacy prevents Gene f2 |

In addition, thrombin induced NF-kappaB translocation and membrane translocation of RhoA in smooth muscle cells which were both prevented by pre-treatment of the cells by atorvastatin. |

| 12921859 | atorvastatin Drug decreases Gene f2 |

How atorvastatin could limit the pro-inflammatory response to thrombin was studied in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. |

| 15792677 | atorvastatin Drug decreases Thing f2 |

Atorvastatin reduces thrombin generation after percutaneous coronary intervention independent of soluble tissue factor. |

|

| ||

| Relationships involving ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein, MDR1) | ||

| 16996216 | atorvastatin Drug causes Synthesis ABCB1 |

Atorvastatin at 10 and 20 microM up-regulated ABCB1 expression resulting in a significant 1.4-fold increase of the protein levels. |

| 16996216 | atorvastatin Drug increases Thing ABCB1 |

Treatment of HepG2 cells with 20 microM atorvastatin caused a 60% reduction on mRNA ex pression (p<0.05) and a 41% decrease in ABCB1-mediated efflux of Rhodamine123 (p<0.01) by flow cytometry. |

| 9607955 | verapamil DrugTreatment induces GeneOrGeneProductActivity ABCB1 |

Previous drug exposure of the cells showed that verapamil, celiprolol, and vinblastine induced the P-gp expression, while metkephamid (MKA) decreased the P-gp expression level as compared to the control. |

| 9636053 | verapamil DrugActivity demonstrates Thing ABCB1 |

P-gp proteoliposomes from P. pastoris showed a strong verapamil- and valinomycin-stimulated ATPase activity, with characteristics (KM, Vmax) similar to those measured in mammalian cells. |

| 9535788 | verapamil Drug inhibits Gene ABCB1 |

In addition, the DNA-damaging agent was found to enhance in a dose-dependent manner cellular efflux of the P-gp substrate rhodamine 123, which was inhibited by the P-gp inhibitor verapamil, thus providing evidence that exposure to MMS led to increased P-gp-related drug transport in rat liver cells. |

| 7769842 | verapamil Drug inhibits GeneOrGeneProductActivity ABCB1 | When P-gp function was assessed by Rhodamine 123 (Rh123) efflux kinetics, we found that only KG1a and KG1 cells, which have an early (immature) CD34+ CD33- CD38- phenotype, and to a lesser extent TF1, with an intermediate (CD34+ CD33+ CD38+) phenotype, displayed significant P-gp activity which could be inhibited by both verapamil and SDZ PSC 833. |

| 16457995 | verapamil DrugAbsorption inhibits Gene ABCB1 |

While cyclosporine and verapamil significantly increased the absorption of methylprednisolone and vinblastine through potent inhibition of intestinal P-gp, tacrolimus failed to achieve this. |

| 17936633 | verapamil Drug regulates GeneOrGeneProductActivity ABCB1 | The results displayed that only compound 3c was P-gp inhibitor as Elacridar, while compound 3a and reference compounds Cyclosporin A and Verapamil modulated P-gp activity saturating the efflux pump as substrates. |

| 16260035 | verapamil Drug suppresses Gene ABCB1 |

Depsipeptide-resistant KU812 cells expressed P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and their resistance was abolished by co-treatment with verapamil. |

| 15257901 | verapamil DrugDose isAssociatedWith Repression ABCB1 |

DL-PPMP and verapamil were found to inhibit MDR1 gene expression in KBV(200) cells at the mRNA level, and complete inhibition occurred after a 48-hour DL-PPMP treatment at 25 micromol/L. |

| 15257901 | verapamil Drug inhibits Expression ABCB1 |

The inhibition of GCS and mdr1 gene expressions is positively correlated with the concentra tions of DL-PPMP and verapamil, which can reverse MDR by inhibiting synthesis of GCS and mdr1 gene, indicating the positive correlation between the expression of GCS gene and MDR in KBV(200) cells. |

| 7749215 | verapamil DrugTreatment decreases Expression ABCB1 |

The level of mdr1 mRNAs is decreased in the presence of verapamil (with a maximum effect obtained at the 24th hour), which suggests that the mechanism of action of verapamil is tran- scriptional and/or post-transcriptional. |

|

| ||

| Relationships involving VEGFA | ||

| 14615256 | verapamil Drug decreases Synthesis VEGFA |

Verapamil (100 microM) decreased IL-6 and VEGF production (Pj0.03 and Pj0.005, respectively) in central keloid fibroblasts cultures at 72 h. |

| 16701707 | atorvastatin Drug induces Gene VEGFA |

We observed that atorvastatin significantly stimulated VEGF release in a dose-dependent man ner. |

| 17389519 | atorvastatin Drug isAssociatedWith Repression VEGFA |

Atorvastatin effectively inhibited laser-induced CNV in mice and was associated with downreg- ulation of CCL2/MCP-1 and VEGF and reduced macrophage infiltration into the RPE/choroid. |

| 12084593 | atorvastatin Drug decreases Expression VEGFA |

Atorvastatin therapy reduced VEGF plasma levels in CAD patients (from 31.1 +/- 6.1 to 19.0 +/− 3.6 pg/ml; p i 0.05). |

|

| ||

| Relationships involving CYP3A4 | ||

| 15001968 | verapamil DrugEfficacy isAssociatedWith Expression CYP3A4 |

Values for the maximum rate of metabolism (V(max)) of verapamil N-dealkylation (formation of D-617) and N-demethylation (formation of norverapamil) activities correlated with the CYP3A4 protein content in both organs. |

| 11907487 | CYP3A4 Gene induces DrugMetabolite verapamil |

Consistent with expression data, formation of verapamil metabolites catalyzed by CYP3A4 and CYP2C was shown. |

| 11005703 | CYP3A4 Enzyme metabolizes Drug atorvastatin |

Atorvastatin, cerivastatin, lovastatin and simvastatin are predominantly metabolised by the CYP3A4 isozyme. |

| 11061579 | CYP3A4 Gene metabolizes Drug atorvastatin |

Atorvastatin is metabolized solely by CYP3A4, and pravastatin metabolism is not well defined. |

|

| ||

| Relationships involving CYP3A | ||

| 16513446 | verapamil Drug inhibits GeneOrGeneProductActivity CYP3A | Verapamil inhibited CYP3A activity, with a maximum effect occurring within 10 days. |

| 16013069 | verapamil DrugMetabolism inhibits Repression CYP3A |

The above data suggested that the metabolism of verapamil and the formation of norverapamil was inhibited by naringin possibly by inhibition of CYP3A in rabbits. |

| 14744949 | verapamil DrugIsoform inhibits Gene CYP3A |

The present study showed that verapamil enantiomers and their major metabolites [norverapamil and N-desalkylverapamil (D617)] inhibited CYP3A in a time- and concentration-dependent man ner by using pooled human liver microsomes and the cDNA-expressed CYP3A4 (+b5). |

| 12433810 | atorvastatin Drug increases Expression CYP3A |

Treatment of 2- to 3-day-old human hepatocyte cultures with 3 × 10(−5) M lovastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, or atorvastatin for 24 h increased the amounts of CYP2B6 and CYP3A mRNA by an average of 3.8- to 9.2-fold and 24- to 36-fold, respectively. |

| 16258024 | CYP3A Gene metabolizes Drug atorvastatin |

Atorvastatin (ATV) is primarily metabolized by CYP3A in the liver to form two active hydroxy metabolites. |

We can get a sense of the significance of this result by considering what would happen if we simply flipped a coin to assign the label “interacting” or “noninteracting” to each path. Roughly 50% of the paths in our training set corresponded to interacting drug pairs, and the other 50% to noninteracting drug pairs. Therefore, if we assigned the labels “interacting” and “noninteracting” entirely at random, we would expect to correctly classify about 50% of paths (with the false positive error rate approximately equal to the false negative error rate). Our method thus represents an improvement in accuracy of nearly 30% over simple guessing.

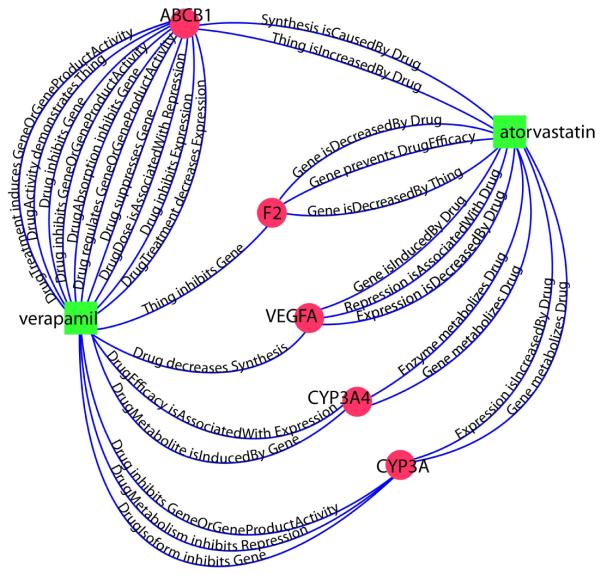

3.3. Predicting Mechanisms of Interaction

In addition to classifying interacting and noninteracting drug pairs with nearly 80% accuracy, our method provides valuable insight into the possible mechanisms by which drugs interact. By choosing a path from one drug to the other through a particular gene, we obtain one potential mechanism for how the two drugs could interact. For example, Figure 6 shows a selection of the highest-ranking paths for a known interacting drug pair: verapamil and atorvastatin. Table 2 shows the Medline sentences corresponding to the edges that comprise these paths. All of these paths received at least 90% “yes” votes from the random forest.

Fig. 6.

A selection of the highest-ranking paths between verapamil and atorvastatin. The total number of connecting paths between verapamil and atorvastatin in the network was 293. All of the paths shown here received more than 90% “interact” votes from the random forest.

Most of the edges connecting verapamil and ABCB1 in Figure 6 seem to indicate that verapamil inhibits the activity of ABCB1. The edges connecting atorvastatin and ABCB1 indicate that atorvastatin upregulates the production of P-glycoprotein, the protein product of ABCB1. The two drugs’ e ects on ABCB1 therefore interfere with each other. Following an-other path, this time through the gene CYP3A4, we see that CYP3A4 induces the breakdown of verapamil into its metabolites, specifically by N-dealkylation and N-demethylation of the drug. Since CYP3A4 is a major metabolizing enzyme for atorvastatin, we might expect that coadministration of the two drugs could lead to heightened levels of one or both of them in the body, leading to toxicity. These represent two di erent possible mechanisms of interaction.

4. Discussion

4.1. Predicting Interactions and Mechanisms

These suggested mechanisms are useful because they provide summaries of what the scientific community knows about pharmacogenomically-mediated interactions between drug pairs of interest. The drug-gene relationships that form the basis of these mechanisms are all existing knowledge; however, our method provides a novel way to connect disparate facts from across the biomedical literature to provide mechanistic explanations of drug-drug interactions.19 In the case of drug pairs that are already known to interact, using this approach provides a list of potential mechanisms of interaction, which may help us uncover new mechanisms that are not yet part of common medical knowledge. By looking at known interacting drug pairs with similar mechanisms of interaction, we can also begin to predict what the phenotypic e ects of our newly-predicted interactions might be.

Once the random forest has been trained on a set of known interacting drug pairs, it can be used to predict whether any other drug pair will interact. In particular, it can be applied to a novel test set that does not include drugs from the original training set. Provided a drug pair is connected by at least one path of the form shown in Figure 4 in the semantic network,the random forest can vote on each connecting path and rank it based on the probability that it represents a mechanism of interaction. This provides us with a powerful tool for predicting mechanisms of interaction that are not yet known. In the future, we hope to use the trained random forest to predict the most likely mechanisms of interaction between drug pairs that are often prescribed together but whose interaction status is not yet known.

4.2. Study Limitations

There are several limitations to the present approach that we hope to address in subsequent iterations of this work. One major limitation is that we only searched Medline for 731 known pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic genes, many of which were liver cytochromes and other enzymes known for their involvement in drug metabolismd. While interactions involving these drugs are interesting, most are already known, and we also tend to miss more specific interactions, such as drug pairs that share the same pharmacologic target. In the future, we plan to expand our data set to encompass a much wider variety of genes - there are 26, 216 genes in the full lexicon from PharmGKB - but the increase in computational time required to search for 26, 216 × 2, 910 = 76, 288, 560 drug-gene pairs is substantial.

On a similar note, because we included only pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic genes in our analysis, we were unable to capture physical or chemical interactions that were not the result of two drugs interacting directly with the same gene. Examples of such missed interactions might include a drug that increases the pH of the stomach, reducing absorption of another drug, or two drugs that have similar, relatively nonspecific phenotypic e ects (such as reducing inflammatory responses throughout the body). We also miss interactions in which two drugs interact with components of the same metabolic pathway but not the same gene, or those in which one drug interacts with a transcription factor that controls the activity of an enzyme responsible for metabolizing another drug. All of these are valid interactions that could be captured if we expanded the semantic network to include gene-gene interactions, as well as interactions of both drugs and genes with certain disease states and phenotypes, all of which we plan to do in the future.

A final limitation of our model is its inability to resolve anaphoras. An example of an anaphora is a two-sentence combination like CYP2C9 is a gene. It metabolizes warfarin. Our model would not pick up the relationship between CYP2C9 and warfarin because the two entities are found in separate sentences. As we refine this work, we would like to find ways to resolve anaphoras, perhaps by considering pairs of entities that are mentioned in the same abstract, not just the same sentence.

5. Conclusion

We have described a method for predicting and explaining drug-drug interactions based on automated extraction of relevant pharmacogenomic facts from the biomedical literature. The method classifies known drug-drug interactions with nearly 80% accuracy using only textualfeatures from descriptions of drug-gene relationships, and provides reasonable mechanistic explanations for its classification decisions. Its success opens many doors to the future use of similar techniques in text mining, perhaps to predict gene-gene interactions, uncover interactions of drugs and genes with diseases, and generate testable hypotheses about the relationships between drugs, genes, and phenotypes.

Table 1.

The final contingency table for the random forest classifier.

| Random Forest Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True Class | 0 | 1 | Class-wide Error |

| No Interaction | 135,842 | 36,429 | 0.211 |

| Interaction | 36,915 | 145,619 | 0.202 |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants LM05652 and GM61374) and the National Library of Medicine (contract HHSN276201000025C).

Footnotes

Note that throughout this analysis, we use the term “gene” interchangeably with “gene product” or “protein”; it is actually the protein product of a gene that interacts with a drug.

Examples of relations that could not be normalized included protects, mimicked, oxidize, encode, and seen. We are in the process of expanding our ontology to include some of these less common relations.

DrugBank obtains its list of drug interactions from a variety of sources, including the Physician’s Desk Reference, e-Therapeutics, MedicinesComplete, Epocrates RX, and Drugs.com (which in turn uses Cerner Multum).

Readers interested in drug interactions mediated by this class of genes are encouraged to visit http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/, a valuable source of information on DDIs mediated by liver cytochromes.

Contributor Information

BETHANY PERCHA, Biomedical Informatics Program, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

YAEL GARTEN, Biomedical Informatics Program and Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

RUSS B. ALTMAN, Departments of Bioengineering, Genetics and Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

References

- 1. [Accessed Wednesday, June 8, 2011];This statistic includes both new prescriptions and refills. http://www.statehealthfacts.org/

- 2.Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2009. Chapter 2: Drug Receptors and Pharmacodynamics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li A, editor. Drug-Drug interactions: scientific and regulatory perspectives. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen AM, Hersh WR. A survey of current work in biomedical text mining. Brief Bioinform. 2005;6:57–71. doi: 10.1093/bib/6.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garten Y, Coulet A, Altman RB. Recent progress in automatically extracting information from the pharmacogenomic literature. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:1467–89. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plake C, Schroeder M. Computational polypharmacology with text mining and ontologies. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:449–57. doi: 10.2174/138920111794480624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tari L, Anwar S, Liang S, Cai J, Baral C. Discovering drug-drug interactions: a text-mining and reasoning approach based on properties of drug metabolism. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i547–53. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Sharp BM. Content-rich biological network constructed by mining PubMed abstracts. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plake C, Shiemann T, Pankalla M, Hakenberg J, Leser U. AliBaba: PubMed as a graph. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2444–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulet A, Altman RB, Musen MA, Shah N. Proc Bio-ontologies SIG. ISMB 2010; Boston, USA: 2010. Integrating heterogeneous relationships extracted from natural language sentences. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulet A, et al. Using text to build semantic networks for pharmacogenomics. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2010;43(6):1009–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein TE, et al. Integrating Genotype and Phenotype Information: An Overview of the PharmGKB Project. The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 2001;1:167–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Bio-X2 cluster at Stanford University was funded by the National Science Foundation, NSF award CNS-0619926.

- 14.Klein D, Manning CD. Accurate Unlexicalized Parsing; Proceedings of the 41st Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2003.pp. 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Marnee MC, MacCartney B, Manning CD. Generating Typed Dependency Parses from Phrase Structure Parses. LREC 2006. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell SJ, Norvig P. Artificial intelligence: A modern approach. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wishart DS, et al. DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D901–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hastie T, Tibshirani RJ, Friedman J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. Springer; New York: 2009. Chapter 16: Random Forests. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Other authors have already pointed out that by finding new ways to connect seemingly-unrelated facts from throughout the scientific literature, we can often generate interesting, and novel, hypotheses. For an example, see Swanson DR. Medical literature as a potential source of new knowledge. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1990;78:29–37.