ABSTRACT

Vibrio cholerae, the cause of an often fatal infectious diarrhea, remains a large global public health threat. Little is known about the challenges V. cholerae encounters during colonization of the intestines, which genes are important for overcoming these challenges, and how these genes are regulated. In this study, we examined the V. cholerae response to nitric oxide (NO), an antibacterial molecule derived during infection from various sources, including host inducible NO synthase (iNOS). We demonstrate that the regulatory protein NorR regulates the expression of NO detoxification genes hmpA and nnrS, and that all three are critical for resisting low levels of NO stress under microaerobic conditions in vitro. We also show that prxA, a gene previously thought to be important for NO detoxification, plays no role in NO resistance under microaerobic conditions and is upregulated by H2O2, not NO. Furthermore, in an adult mouse model of prolonged colonization, hmpA and norR were important for the resistance of both iNOS- and non-iNOS-derived stresses. Our data demonstrate that NO detoxification systems play a critical role in the survival of V. cholerae under microaerobic conditions resembling those of an infectious setting and during colonization of the intestines over time periods similar to that of an actual V. cholerae infection.

IMPORTANCE

Little is known about what environmental stresses Vibrio cholerae, the etiologic agent of cholera, encounters during infection, and even less is known about how V. cholerae senses and counters these stresses. Most prior studies of V. cholerae infection relied on the 24-h infant mouse model, which does not allow the analysis of survival over time periods comparable to that of an actual V. cholerae infection. In this study, we used a sustained mouse colonization model to identify nitric oxide resistance as a function critical for the survival of V. cholerae in the intestines and further identified the genes responsible for sensing and detoxifying this stress.

Introduction

Vibrio cholerae causes the disease cholera and represents a large global health problem in impoverished countries. Cholera continues to cause epidemics and has the ability to spread to new locations, having caused over 4,500 deaths in Haiti since the earthquake in 2010 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). Cholera is characterized by profuse dehydrating diarrhea and can be treated with vigorous oral rehydration and supplementary antibiotics. Despite these interventions, cholera remains a source of considerable worldwide morbidity and mortality. Cholera toxin, which directly causes secretory diarrhea, and its transcriptional regulation are well understood (1, 2). However, the bacteria that cause cholera, or any intestinal infection, encounter chemical and physical barriers during the establishment and maintenance of colonization. The host-derived stresses that V. cholerae encounters while infecting a host are not well characterized, and even less well understood is how V. cholerae senses these stresses.

One of the toxic chemical species elaborated by the host during bacterial infection is nitric oxide (NO). NO is a toxic radical that disrupts the function of proteins containing cysteine residues, enzymes catalyzing iron-dependent reactions, and members of the electron transport chain (3). Furthermore, NO reacts with other small molecules produced by the immune system to form other toxic reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as nitroxyl and peroxynitrite (4, 5). In the host, NO is generated by acidified nitrite in the stomach and by enzymes of the NO synthase (NOS) family, which derive NO from arginine (6). There are three isoforms of NOS, and the form associated with the immune system is inducible NOS (iNOS), which is capable of generating large quantities of NO in an inflammatory setting. Epithelial cells are known to express iNOS, as are immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells (6–9). Clinical studies have demonstrated that patients with cholera have increased NO metabolite levels in their serum and urine, as well as an increase in the expression of iNOS in their small intestines during V. cholerae infection, suggesting that V. cholerae encounters NO during infection of humans (10–12). To cope with NO produced during infection, many pathogenic bacteria have evolved mechanisms to convert NO into other, less toxic, nitrogen oxides (3). The only enzyme predicted to have this activity in V. cholerae is HmpA (VCA0183), a member of the flavohemoglobin family of enzymes that is well characterized in other bacteria such as Escherichia coli (13). Under low-oxygen conditions such as those one might find in the gut, HmpA catalyzes the conversion of NO to N2O or NO3−, both of which are less toxic to the bacterium (14). Within HmpA is an iron-heme moiety that directly catalyzes the reaction, as well as a flavin group and an NADPH oxidase domain that mediate the transfer of electrons to and from NO (14). HmpA homologs are important for detoxification of NO during infections with other bacterial pathogens such as E. coli, Yersinia pestis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella enterica, as well as V. fischeri colonization of its squid host (15–19). In V. cholerae, hmpA emerged as a gene expressed in both infant mice and rabbits in two different in vivo screens (20, 21). A recent study demonstrated that in the infant mouse model of V. cholerae infection, HmpA was important for resistance of NO generated in the stomach from acidified nitrite (22). However, since the suckling mouse model of cholera is limited to 24-h studies, it is unknown whether NO might be generated later during infection and present a second NO barrier to V. cholerae infection beyond the stomach. Furthermore, it remains unknown how the expression of hmpA is regulated. Here we demonstrate that hmpA expression is controlled by the NO sensor NorR (VCA0182), a predicted σ54-dependent transcriptional regulator (23). A previous bioinformatic study predicted a NorR-binding site upstream of hmpA and also upstream of one other gene, nnrS (vc2330). The function of NnrS, a membrane protein, was previously unknown, but it may have a role in the metabolism of nitrogen oxides (24). We also demonstrate that the expression of nnrS is controlled by NorR and that nnrS is important for NO resistance in vitro when hmpA is deleted. In addition, we show that hmpA and norR are critical for long-term colonization of the adult mouse intestine.

RESULTS

NorR is required for NO-inducible expression of hmpA and nnrS and represses its own expression.

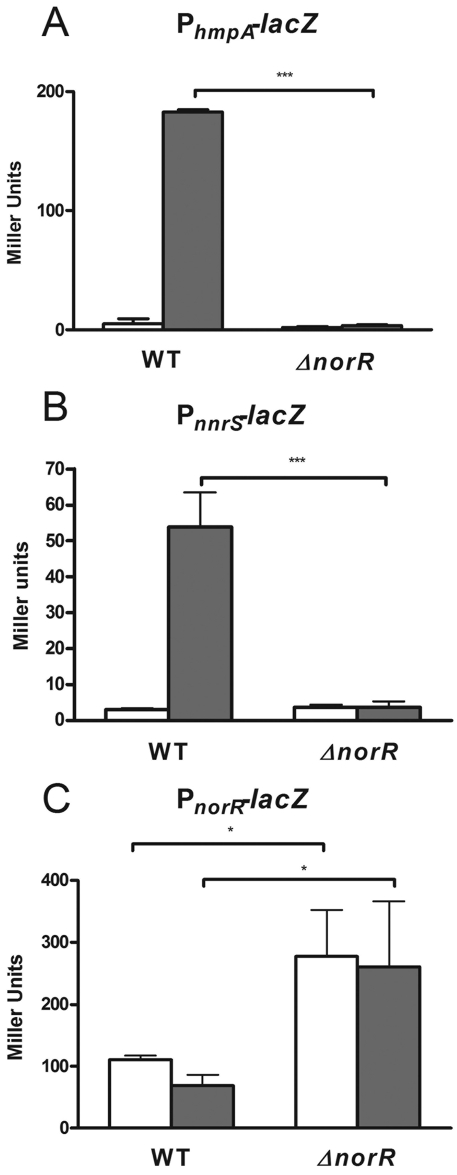

The regulatory networks that control NO detoxification vary widely between bacterial species (13). V. cholerae has a limited repertoire of NO-related genes that includes hmpA, which encodes a flavohemoglobin, nnrS, a widely conserved gene of previously unknown function, and norR, which encodes a NO-responsive DNA-binding regulatory protein (23, 25, 26). A computational study predicted that NorR would control the expression of hmpA and nnrS (13). This is different from enteric species and other Vibrio species, in which NorR controls or is predicted to control the expression of the NO reductase gene norVW. There is no norVW homolog present in the V. cholerae chromosome. To determine the effect of NO on the expression of hmpA, nnrS, and norR, we constructed transcriptional reporter plasmids containing the promoters of these genes fused to the lacZ gene. Strains grown in minimal medium had low background transcription of hmpA and nnrS, but the addition of a 50 µM concentration of the NO donor DEA-NONOate [diethylammonium (Z)-1-(N,N-diethylamino)diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate] resulted in a dramatic upregulation of both of these promoters (Fig. 1A and B). DEA-NONOate releases NO over a short period of time. Under aerobic conditions, there was no upregulation of either the hmpA or the nnrS promoter (data not shown), likely because the NO diffused out of the system or reacted with O2. Under the closed-tube microaerobic conditions of this experiment, 50 µM DEA-NONOate did not inhibit the growth of any of the strains. In a norR deletion background, however, virtually no upregulation of the hmpA or tnnrS promoter was observed (Fig. 1A and B), suggesting that NorR is absolutely required for the activation of both of these promoters. These experiments were performed with minimal medium because the background activity of the hmpA and nnrS promoters was low. However, performance of the experiments with LB medium under microaerobic conditions still resulted in >10-fold upregulation of both promoters (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these data suggest that NorR controls the NO-inducible upregulation of both hmpA and nnrS. We further investigated how norR is regulated by comparing norR-lacZ expression in the wild-type and norR mutant strains with or without NO. The activity of the norR promoter was not altered by the addition of NO (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, norR promoter activity was significantly increased in the norR background (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that NorR represses its own expression independently of NO.

FIG 1 .

Effects of NO and NorR on the expression of NO detoxification genes. Strains containing a promoter-lacZ reporter were grown in minimal medium under microaerobic conditions. hmpA (A), nnrS (B), or norR (C) promoter activity was measured after the addition of a 50 µM concentration of the control compound diethylamine (white bars) or the NO donor DEA-NONOate (gray bars) and is reported in Miller units (34). Experiments were performed with wild-type (WT) strain C6706 or a strain containing a clean deletion of the entire norR open reading frame. Error bars represent standard deviations. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 (for experiments performed in triplicate).

norR, hmpA, and nnrS are critical for NO resistance in vitro.

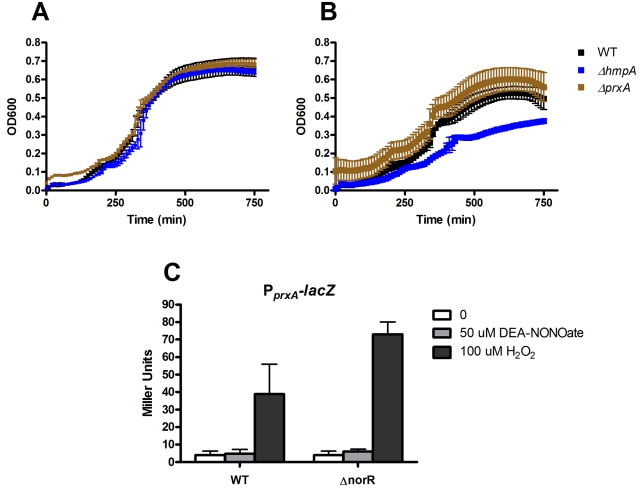

A recent study by Davies et al. (22) implicated hmpA as an important gene for resistance to NO under aerobic conditions in the presence of high (millimolar) concentrations of NO donors. To examine whether the NorR regulon, including hmpA, is important for resistance to NO in a microaerobic environment more similar to what bacteria are likely to encounter during infection of the small intestine, we performed growth curve assays with sealed 96-well plates. We added 10 µM (Z)-1-[N-(2-aminoethyl)-N-(2-ammonioethyl)amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (DETA-NONOate), which continuously releases NO with a half-life of 20 h, to the cultures and measured the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) every 10 min at 37°C in a plate reader. The hmpA, norR, and nnrS single mutants and hmpA nnrS double mutant were examined. None of these mutations conferred a growth defect in the absence of NO (Fig. 2A). Similar to the results of Davies et al., who grew bacteria aerobically, deletion of hmpA resulted in a growth defect in the presence of NO (Fig. 2B). Deletion of norR resulted in a more severe defect, and interestingly, deletion of both hmpA and nnrS resulted in the most severe phenotype. The nnrS single mutation, however, did not result in an NO-sensitive defect. These data suggest that the NorR regulon, containing hmpA and nnrS, is critical for resistance to NO. Similar but less dramatic results were obtained using 10 µM spermine-NONOate, which releases NO with a half-life of approximately 39 min (data not shown). Almost no defect could be detected with micromolar concentrations of DEA-NONOate, which releases NO with a half-life of approximately 2 min. This suggests that during continuous exposure to NO, such as that which might occur during infection, physiologically relevant concentrations of NO (22, 27) are sufficient to affect the growth of V. cholerae. The importance of nnrS is revealed only in an hmpA mutant background, suggesting that it may play a redundant role in NO detoxification. Alternatively, NnrS may catalyze the detoxification of a related RNS. We tested whether nnrS mutants are more sensitive to peroxynitrite (ONOO−), Angeli’s salt (a donor of nitroxyl anion, NO−), and nitrite (NO2−) but found no difference from the wild type (data not shown), suggesting that the role of nnrS in resistance to RNS is important but subtle. The function of nnrS is a subject of ongoing research.

FIG 2 .

Role of the NorR regulon in NO resistance in vitro. To test the effect of NO on the growth of mutant strains, bacteria were inoculated in triplicate into a sealed 96-well plate in minimal medium at 37°C in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 10 µM DETA-NONOate. Growth was measured by determining the OD600 every 10 min. The strains used were as follows: black, wild type (WT); blue, ΔhmpA mutant; green, ΔnnrS mutant; red, ΔnorR mutant; purple, ΔhmpA ΔnnrS double mutant. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

prxA expression is induced by H2O2 and not by NO and is not important for NO resistance under microaerobic conditions.

Davies et al. recently found that deletion of prxA, a gene that encodes a putative peroxiredoxin, resulted in sensitivity to NO (22). We examined the NO sensitivity of a strain in which prxA and adjacent gene vc2638 from the same operon were deleted under microaerobic conditions in minimal medium. In their study, a high concentration of DEA-NONOate (1 mM) was used. This results in the full release of 2 mM NO over a period of approximately 10 min under aerobic conditions. However, under microaerobic conditions in minimal medium containing 10 µM DETA-NONOate, conditions which significantly inhibited the growth of strains lacking hmpA or norR (Fig. 2B), there was no detectable growth defect in a prxA mutant (Fig. 3A and B). To study whether prxA expression could be induced by NO, we constructed a reporter consisting of the prxA promoter fused to lacZ. The addition of 50 µM DEA-NONOate, which caused dramatic upregulation of hmpA and nnrS (Fig. 1), did not result in activation of the prxA promoter (Fig. 3C). However, addition of 100 µM H2O2 did result in upregulation of the prxA promoter in both wild-type bacteria and a strain lacking norR. The prxA gene is located divergent from the oxyR gene, which has been shown in other bacteria to mediate responses to oxidative stress (28). We speculate that the results of Davies et al. resulted not directly from NO but from other species generated under aerobic conditions during a burst of millimolar concentrations of NO from a short-lived NO donor.

FIG 3 .

Importance of prxA in response to NO and H2O2 under microaerobic conditions. The growth of a strain of V. cholerae lacking prxA and its adjacent gene vc2638 was compared to that of the wild type (WT) and a ΔhmpA mutant in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 10 µM DETA-NONOate under microaerobic conditions in minimal medium. In the experiment shown in panel C, wild-type and ΔnorR mutant strains of V. cholerae containing a reporter plasmid that contains lacZ fused to the prxA promoter were grown in minimal medium. After the addition of 50 µM DEA-NONOate (gray bars), 100 µM H2O2 (black bars), or nothing (white bars), prxA promoter activity was measured by Miller assay.

norR and hmpA are critical for sustained colonization of the adult mouse intestine.

Previous experiments (22) tested the effect of hmpA deletion in an infant mouse model and demonstrated a moderate defect (competitive index = 0.13) that was partially dependent on the presence of acidified nitrite in the mouse stomach. We repeated these experiments and found a similar competitive index of 0.40 ± 0.01, confirming these results. However, the infant mouse model only allows for a 24-h experiment and is not suitable for study of the extended survival of a bacterial strain in the intestines. The incubation time of V. cholerae infection is typically 2 to 3 days, and symptoms can last a long time after this (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), suggesting that V. cholerae may be exposed to challenges such as RNS for prolonged periods of time during infection. Furthermore, the majority of people inoculated with V. cholerae do not develop symptoms but continue to shed vibrios in their stool for days, a time when RNS may still be generated in the host (29, 30). To determine the importance of hmpA, as well as norR and nnrS, in the setting of long-term colonization, we employed an adult mouse model (29) in which we could monitor colonization levels by collecting fecal pellets.

We used a competition assay in our mouse studies. After treatment with streptomycin and neutralization of stomach acid, mice were coinoculated with a wild-type strain and a mutant strain. Either the mutant or the wild-type strain lacked the lacZ gene, allowing differentiation on plates containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal). At the end of each experiment, the small intestine of each mouse was homogenized and competitive indices were calculated from the homogenates. In each experiment performed, the competitive indices from intestinal homogenates were always virtually identical to those from the fecal samples (data not shown).

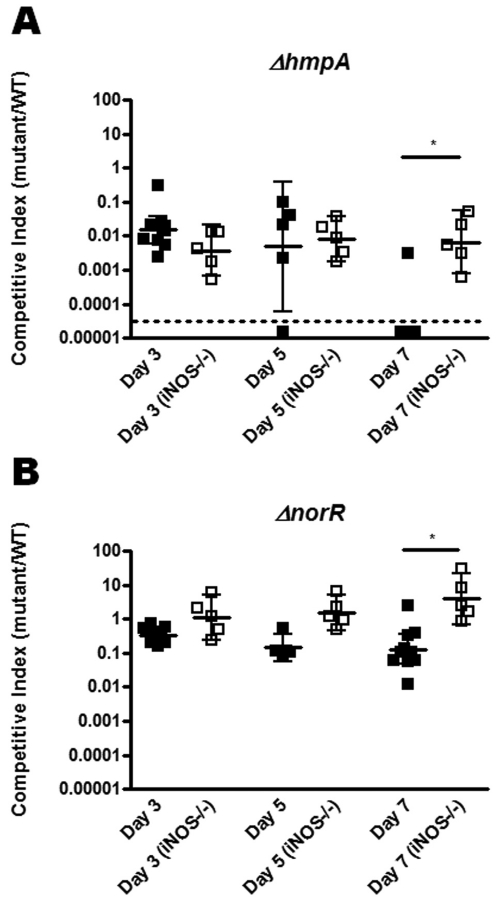

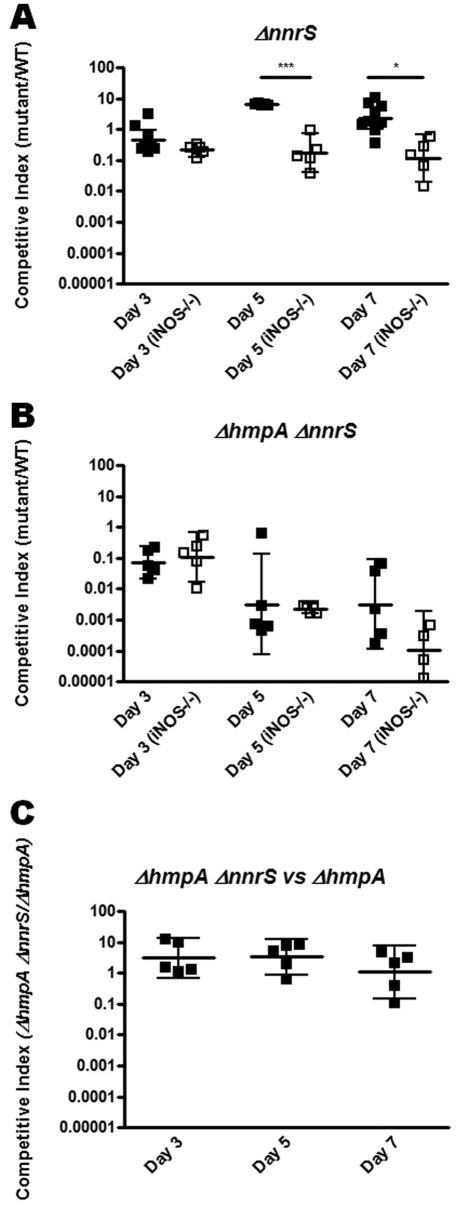

Interestingly, deletion of hmpA resulted in a colonization defect at 3 days postinoculation that worsened to nearly undetectable levels by 7 days, suggesting that HmpA is important for sustained colonization of the intestines (Fig. 4A). A competitive index was considered below the limit of detection (denoted by the dotted line in Fig. 4A) if no hmpA mutant colonies were detected. The norR mutant displayed a more moderate but significant defect as well. As in the in vitro studies, the nnrS single deletion mutant displayed no colonization defect and perhaps even a slight advantage over wild-type bacteria in wild-type mice (Fig. 5A). We hypothesized that, similar to our in vitro data, this phenotype might be reversed in an hmpA mutant background and that the hmpA nnrS double mutant might have an even more severe defect than the hmpA single mutant. However, competition of the hmpA nnrS double mutant against wild-type bacteria displayed a profound defect similar to that of the hmpA single mutant (Fig. 5A). To determine if a smaller nnrS-mediated defect might be masked by the larger defect due to hmpA mutation, we competed the hmpA nnrS double mutant against the hmpA single mutant. We were surprised to find, however, that the double mutant did not fare significantly worse or better than the single hmpA mutant (Fig. 5B).

FIG 4 .

Importance of hmpA and norR for sustained colonization of the adult mouse. Six-week-old C57BL/6 (black squares) or C57BL/6 iNOS−/− (white squares) mice were coinfected with wild-type (WT) V. cholerae and either a ΔhmpA (A) or a ΔnorR (B) mutant strain. Fecal pellets were collected on days 3, 5, and 7 postinoculation and plated on differential medium. The competitive index was calculated as the ratio of mutant to wild-type colonies normalized to the input ratio. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Data points below the dotted line indicate that no mutant colonies were detected. *, P < 0.05.

FIG 5 .

Effect of deletion of nnrS on colonization of wild-type and iNOS−/− mutant mice. As described in the legend to Fig. 4, mice were inoculated with a mixture of wild-type (WT) V. cholerae and a ΔnnrS (A) or a ΔhmpA ΔnnrS (B) mutant. In the experiment shown in panel C, mice were inoculated with a mixture of the V. cholerae ΔhmpA and ΔhmpA ΔnnrS mutants and the competitive index is reported as the ratio of ΔhmpA ΔnnrS to ΔhmpA mutant colonies normalized to the input. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

To assess the contribution of iNOS to the colonization defects observed, we repeated the experiments with iNOS−/− mice. By day 7 postinoculation, the severe colonization defect of the hmpA mutant was attenuated more than 10-fold in iNOS−/− mice (Fig. 4A), suggesting that iNOS presents a long-term challenge for V. cholerae that is dealt with by hmpA. The norR mutant displayed a similar effect, in which the defect observed in the wild type was completely attenuated in iNOS−/− mice (Fig. 4B). This again suggests that over the time period during which a V. cholerae infection occurs, iNOS-generated RNS present a significant challenge for V. cholerae to overcome. Unexpectedly, however, the nnrS single mutant displayed a small but significant defect in iNOS−/− mice (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the competition defect of the hmpA nnrS double mutant was not mitigated in iNOS−/− mice as it was in the hmpA single mutant at 7 days postinoculation (Fig. 5A). With wild-type mice, the competitive index at day 7 of the hmpA nnrS double mutant was significantly higher than that of the nnrS single mutant (P = 0.0397). These data suggest that in our long-term colonization model, nnrS may actually be detrimental to detoxification of iNOS-derived stresses. The exact mechanism behind this requires further investigation.

DISCUSSION

Despite a wealth of research on the virulence factors that allow V. cholerae to cause disease, relatively little is known about the challenges that V. cholerae encounters during infection of the intestines and how it senses and overcomes them. In this study, we have identified how V. cholerae senses and responds to NO, a common challenge for intestinal pathogens. We have further demonstrated that one of the NO detoxification genes, hmpA, and its transcriptional activator NorR are critical for sustained colonization of the intestines of mice.

Previous bioinformatic analysis led to the identification of a remarkably limited repertoire of NO-related genes found in the V. cholerae genome, even compared to highly related Vibrio species (13). Using reporter assays, we demonstrated that the expression of two of these genes, nnrS and the flavohemoglobin-encoding gene hmpA, is highly inducible by the addition of NO to microaerobically growing cells. This upregulation was dependent on the σ54-dependent transcriptional regulator NorR (23, 25, 26). Growth curve analysis demonstrated that these genes are essential for NO resistance in vitro. Intriguingly, a strain of V. cholerae lacking both hmpA and nnrS was the most attenuated for growth in the presence of NO; concomitantly, deletion of norR resulted in a nearly equivalent growth defect in the presence of NO. These data demonstrated that HmpA is the principal detoxifier of NO but that NnrS may play an auxiliary role. The only study of NnrS published to date identified it as a heme- and copper-containing membrane protein in Rhodobacter sphaeroides (24). However, nnrS homologs are found in the genomes of human pathogens such as Pseudomonas, Brucella, Burkholderia, Bordetella, and Neisseria, suggesting that it may play NO detoxification roles in a variety of infectious settings. The exact function of NnrS is an area of current investigation in our laboratory.

The role of NO detoxification genes in V. cholerae pathogenesis has been examined in an infant mouse model in which bacteria are allowed to colonize the intestines for 24 h (22). After this brief period, there was a moderate colonization defect in the hmpA mutant attributed to the low pH of the stomach. We were interested in whether NO resistance could be important in colonization of the intestine over a time period resembling that of a human infection. Interestingly, we found that the importance of HmpA was much greater than previously thought; there were virtually no hmpA mutants recovered from fecal samples or small intestinal homogenates after 7 days. This defect was partially due to iNOS-derived stress, as the colonization defect was partially mitigated in iNOS−/− mice at 7 days. The remaining defect is not likely to be due to stomach acidity because the mice were administered bicarbonate prior to inoculation. Mice and humans possess two other NOS isoforms, neuronal NOS and endothelial NOS (31), which may also account for some of the defect that persists in iNOS−/− mice.

We were surprised to discover the effects of the nnrS mutation on colonization. Although the hmpA nnrS double mutant was severely inhibited in vitro, this mutant fared no better in iNOS−/− mice than in wild-type mice. Furthermore, the nnrS single mutant slightly outcompeted wild-type V. cholerae in wild-type mice but was attenuated in iNOS−/− mice. It is difficult to interpret these data, given the unknown function of NnrS, but we hypothesize that the complex metabolism of RNS results in the buildup of detrimental chemical products in some contexts. Furthermore, an acknowledged disadvantage of competition studies is that a defect in the nnrS mutant may be complemented in trans by the wild-type coinoculated strain. Future studies may address this possibility. Given the in vitro importance of NnrS, however, we speculate that there are infectious settings in which NnrS is critical to the survival of V. cholerae. In addition, we were surprised to find that the hmpA nnrS double mutant had a far more severe colonization defect than the norR mutant in wild-type mice (Fig. 4), since NorR is absolutely required for the upregulation of hmpA and nnrS in response to NO (Fig. 1). One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the colonization defects is that baseline transcription of hmpA and nnrS in the norR deletion mutant, however low, is sufficient to detoxify a significant proportion of the NO stress found in vivo. Alternatively, signals other than NO, and thus regulators other than NorR, might cause the upregulation of hmpA and nnrS in vivo. This could allow better colonization efficiency than when hmpA and nnrS are deleted entirely. Our laboratory is currently working to find these alternative signals and regulators of hmpA and nnrS.

Davies et al. (22) recently demonstrated a growth defect in a strain of V. cholerae lacking the prxA gene, which encodes a putative peroxireductase. They used a large, short-lived bolus of NO under aerobic conditions and found that the strain exhibited a delayed log phase. In the presence of a low level of continuously released NO, a strain lacking prxA exhibited no defect compared to the wild type. Furthermore, the expression of prxA was not increased in the presence of NO but was dramatically increased in the presence of H2O2. We suspect that PrxA is important for resistance to reactive oxygen species that may have been generated under aerobic conditions in the presence of large amounts of NO, but we conclude that it plays no role directly related to NO detoxification.

In summary, we have demonstrated the importance of the NorR regulon in NO sensing and resistance to NO toxicity. Furthermore, we identified the importance of NO detoxification genes during extended colonization of the mouse intestine. Our work highlights the role of resistance to chemical stresses in the successful survival of V. cholerae during infection and ultimately its ability to cause disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The parent strain used in this study was V. cholerae O1 El Tor C6706. Sucrose counterselection (32) was used to generate all clean deletions. Promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions were generated by cloning the approximately 500 bp proximal to the ATG start codon upstream of a promoterless lacZ gene in a plasmid (33). Strains were propagated in LB containing appropriate antibiotics at 37°C, unless otherwise noted.

Gene expression studies.

For in vitro gene expression studies under microaerobic conditions, saturated overnight cultures in LB were inoculated 1:100 into minimal medium containing 79 mM KH2PO4, 15 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.65 mM MgSO4, 0.07 mM CaCl2, 0.018 mM FeSO4, 0.013 mM MnSO4, and 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose in filled, sealed glass vials. After 4 h of growth, 50 µM DEA-NONOate (from a 50 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide; Cayman Chemical) was added to the cultures. Diethylamine was used as a negative control. Two hours later, the OD600 of the cultures was measured and a Miller assay (34) was used to measure LacZ production. For experiments in LB, bacteria were inoculated 1:1,000, with 2.5 h of growth prior to NO addition and 1.5 h of growth thereafter.

Growth curves.

To measure in vitro growth, strains from saturated LB cultures were inoculated 1:100 into 0.25 ml of minimal medium (described above) in a 96-well plate. Plates were sealed with an optically clear film and incubated at 37°C, and the OD600 was measured every 10 min by an automated plate reader (Bio-Tek Synergy HT). To measure the effect of NO on growth, 10 µM DETA-NONOate (Cayman Chemical) was included.

In vivo mouse colonization studies.

Mouse colonization competition studies were performed using a protocol modified from reference 29. Six week-old C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 iNOS−/− (strain B6.129P2-Nos2tm1Lau/J) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Two days before inoculation, 0.5% (wt/vol) streptomycin and 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose were added to the drinking water; this treatment was maintained throughout this experiment, with regular replacement every 2 to 3 days. One day before inoculation, food was removed from the cages. On the day of inoculation, stomach acid was neutralized with 0.05 ml 10% (wt/vol) NaHCO3 by oral gavage. Twenty minutes later, 0.4 ml of a saturated culture of each of the two strains was mixed with 0.2 ml 10% (wt/vol) NaHCO3, and 0.1 ml of this mixture was administered to each mouse by oral gavage. The size of the inoculum was determined by serial dilution and plating on LB plates containing 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin and 0.04 mg/ml X-Gal. Food was replaced 2 h after inoculation. On days 3, 5, and 7 postinoculation, two or three fecal pellets were collected from each mouse, resuspended in LB, serially diluted, and then plated on plates containing streptomycin and X-Gal. The competitive index was calculated as the ratio of mutant to wild-type colonies normalized to the ratio contained in the inoculum. At the end of the experiment, mice were sacrificed and competitive indices were calculated from homogenates of their small intestines.

Statistical analyses.

For all experiments, a two-tailed Student t test was performed to determine statistical significance. Data points below the limit of detection were considered at the limit of detection for statistical analyses. A difference in means was considered statistically significant if the P value was <0.05.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Effects of NO and NorR on the expression of hmpA and nnrS in LB medium. Strains containing a promoter-lacZ reporter were grown in LB under microaerobic conditions. hmpA (A) or nnrS (B) promoter activity was measured after the addition of a 50 µM concentration of the control compound diethylamine (white bars) or the NO donor DEA-NONOate (gray bars) and is reported in Miller units (34). Experiments were performed with wild-type strain C6706 or a strain containing a clean deletion of the entire norR open reading frame. Error bars represent standard deviations of experiments performed in triplicate. Download Figure S1, DOCX file, 0.1 MB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank James Shapleigh and Fevzi Daldal for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by the NIH/NIAID (R01 AI072479) and an NSFC key project (30830008).

Footnotes

Citation Stern AM, et al. 2012. The NorR regulon is critical for Vibrio cholerae resistance to nitric oxide and sustained colonization of the intestines. mBio 3(2):e00013-12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00013-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bishop AL, Camilli A. 2011. Vibrio cholerae: lessons for mucosal vaccine design. Expert Rev. Vaccines 10:79–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matson JS, Withey JH, DiRita VJ. 2007. Regulatory networks controlling Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 75:5542–5549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Poole RK. 2005. Nitric oxide and nitrosative stress tolerance in bacteria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:176–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. 2009. Chemical biology of peroxynitrite: kinetics, diffusion, and radicals. ACS Chem. Biol. 4:161–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hughes MN. 1999. Relationships between nitric oxide, nitroxyl ion, nitrosonium cation and peroxynitrite. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1411:263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pautz A, et al. 2010. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide 23:75–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bagley KC, Abdelwahab SF, Tuskan RG, Lewis GK. 2006. Cholera toxin indirectly activates human monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro through the production of soluble factors, including prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13:106–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rumbo M, Courjault-Gautier F, Sierro F, Sirard J-C, Felley-Bosco E. 2005. Polarized distribution of inducible nitric oxide synthase regulates activity in intestinal epithelial cells. FEBS J. 272:444–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salzman AL, Eaves-Pyles T, Linn SC, Denenberg AG, Szabó C. 1998. Bacterial induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase in cultured human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 114:93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janoff EN, et al. 1997. Nitric oxide production during Vibrio cholerae infection. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 273:G1160–G1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qadri F, et al. 2002. Increased levels of inflammatory mediators in children and adults infected with Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rabbani GH, et al. 2001. Increased nitrite and nitrate concentrations in sera and urine of patients with cholera or shigellosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96:467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rodionov DA, Dubchak IL, Arkin AP, Alm EJ, Gelfand MS. 2005. Dissimilatory metabolism of nitrogen oxides in bacteria: comparative reconstruction of transcriptional networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 1:e55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poole RK, Hughes MN. 2000. New functions for the ancient globin family: bacterial responses to nitric oxide and nitrosative stress. Mol. Microbiol. 36:775–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bang I-S, et al. 2006. Maintenance of nitric oxide and redox homeostasis by the salmonella flavohemoglobin Hmp. J. Biol. Chem. 281:28039–28047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richardson AR, Dunman PM, Fang FC. 2006. The nitrosative stress response of Staphylococcus aureus is required for resistance to innate immunity. Mol. Microbiol. 61:927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sebbane F, et al. 2006. Adaptive response of Yersinia pestis to extracellular effectors of innate immunity during bubonic plague. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 103:11766–11771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stevanin TM, Read RC, Poole RK. 2007. The hmp gene encoding the NO-inducible flavohaemoglobin in Escherichia coli confers a protective advantage in resisting killing within macrophages, but not in vitro: links with swarming motility. Gene 398:62–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, et al. 2010. Vibrio fischeri flavohaemoglobin protects against nitric oxide during initiation of the squid–Vibrio symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 78:903–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mandlik A, et al. 2011. RNA-Seq-based monitoring of infection-linked changes in Vibrio cholerae gene expression. Cell Host Microbe 10:165–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schild S, et al. 2007. Genes induced late in infection increase fitness of Vibrio cholerae after release into the environment. Cell Host Microbe 2:264–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davies BW, et al. 2011. DNA damage and reactive nitrogen species are barriers to Vibrio cholerae colonization of the infant mouse intestine. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1001295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. D’Autréaux B, Tucker NP, Dixon R, Spiro S. 2005. A non-haem iron centre in the transcription factor NorR senses nitric oxide. Nature 437:769–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bartnikas TB, et al. 2002. Characterization of a member of the NnrR regulon in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.3 encoding a haem-copper protein. Microbiology 148:825–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Büsch A, Pohlmann A, Friedrich B, Cramm R. 2004. A DNA region recognized by the nitric oxide-responsive transcriptional activator NorR is conserved in beta- and gamma-proteobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 186:7980–7987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mukhopadhyay P, Zheng M, Bedzyk LA, LaRossa RA, Storz G. 2004. Prominent roles of the NorR and Fur regulators in the Escherichia coli transcriptional response to reactive nitrogen species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:745–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reinders CI, et al. 2005. Rectal mucosal nitric oxide in differentiation of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3:777–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zheng M, Åslund F, Storz G. 1998. Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science 279:1718–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Olivier V, Salzman NH, Satchell KJF. 2007. Prolonged colonization of mice by Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 depends on accessory toxins. Infect. Immun. 75:5043–5051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK. 2004. Cholera. Lancet 363:223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Griffith OW, Stuehr DJ. 2011. Nitric oxide synthases: properties and catalytic mechanism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 57:707–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 1996. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene 169:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsiao A, Xu X, Kan B, Kulkarni RV, Zhu J. 2009. Direct regulation by the Vibrio cholerae regulator ToxT to modulate colonization and anticolonization pilus expression. Infect. Immun. 77:1383–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor: Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of NO and NorR on the expression of hmpA and nnrS in LB medium. Strains containing a promoter-lacZ reporter were grown in LB under microaerobic conditions. hmpA (A) or nnrS (B) promoter activity was measured after the addition of a 50 µM concentration of the control compound diethylamine (white bars) or the NO donor DEA-NONOate (gray bars) and is reported in Miller units (34). Experiments were performed with wild-type strain C6706 or a strain containing a clean deletion of the entire norR open reading frame. Error bars represent standard deviations of experiments performed in triplicate. Download Figure S1, DOCX file, 0.1 MB.