Abstract

Background:

Caring for stroke patients leads to caregiver (CG) strain. The aims of this study are to identify factors related to increased CG burden in stroke survivors in a census-defined population and to assess the relationship between patient characteristics and CG stress.

Materials and Methods:

In a prospective population-based study, 223 first ever stroke (FES) were identified over a 1-year period. At 28 days, 127 (56.9%) were alive and 79 (35%) died, and 17 were lost to follow-up. One hundred and eleven CGs of 127 FES survivors agreed to participate. The level of stress was assessed by two scales: Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale (OCBS) and the Caregivers Strain Index (CSI) in CGs of survivors with mild stroke Modified Rankin Scale (MRS 1-2) and in those with significant disability (MRS 3-5).

Results:

The mean age of CGs was 45.6 years, approximately 22 years younger than that of the patients (67.5 years). Eighty-nine (80%) of the CGs were females and only 22 (20%) were males. Urinary incontinence (P=0.000008), morbidity at 28 days by MRS (P=0.0051), female gender (P=0.0183) and moderate to severe neurological deficit by National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on admission (P=0.0254) were factors in FES cases leading to major CGs stress. CG factors responsible for major stress were long caregiving hours (P≤0.000001), anxiety (P≤0.000001), disturbed night sleep (P≤0.000001), financial stress (P=0.0000108), younger age (P=0.0021) and CGs being daughter-in-laws (P=0.012).

Conclusion:

Similar studies using uniform methodologies would help to identify factors responsible for major CG stress. Integrated stroke rehabilitation services should address CG issues to local situations and include practical training in simple nursing skills and counseling sessions to help reduce CG burden.

Keywords: Caregiver burden, organized stroke care, stroke survivor

Introduction

As life expectancy increases, India will face enormous socioeconomic burden to meet the costs of integrated rehabilitation of subjects with stroke. Caring for stroke patients leads to caregiver (CG) strain. In stroke patient care and rehabilitation, focus on CG stress is a neglected domain. The aims of this study are to identify factors related to increased CG burden in stroke survivors in an Asian country and to assess the relationship between patient characteristics and CG stress. The study will provide meaningful data for supportive interventions for stroke survivors and their CGs and useful input for further research.

Background

While much attention had been paid to the incidence and prevalence of stroke, there have been much fewer studies focusing on the long-term consequences and the need for ongoing assistance and caregiving. Literature search has revealed some reports from the developed countries, but hardly any from the developing countries.[1]

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study (1997) reported 9.4 million deaths in India, of which 619, 000 were from “Stroke,” and the Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) that were lost almost amounted to 28.5 million: Nearly six-times higher than that due to Malaria.[2] In 2005, stroke deaths accounted for 87% of all deaths from developing countries, and this burden will increase with ageing population. An estimated 5.7 million people died from stroke in 2005, and the projected deaths will rise to 6.5 million by 2015.[3]

To plan effective intervention and prevention strategies for stroke survivors and their CGs, it is essential to initiate epidemiological surveys using standard methods of data collection, case finding and reporting templates that should be uniform for interregional comparisons.[4]

CG is defined as “a person who lives with the patient and is most closely involved in taking care of him/her at home.” CG can also be defined as “an unpaid person who helps with the physical care or coping with the disease.”[5] The CG is vulnerable to stress and strain developing as a result of nursing/attending to a patient over a prolonged period of time. CG burden or stress is a multidimensional concept as it entails the physical, social, psychological and financial factors. CG burden as described by Zarit et al.: “the state resulting from necessary caring tasks or restrictions that cause discomfort for the CG.”[6] CG burden can be: (i) objective – costs related to caregiving, how much physical assistance and intervention is needed to assist in Activities of Daily Living (ADLS) due to increased physical disability, cognitive impairments and housekeeping tasks. These factors are assessed by the Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale.[7] It is a 15-item scale that records responses to activities and tasks to help the stroke survivor. They are then graded on a time subscale and difficulty subscale. (ii) Subjective burden: The positive or negative feelings and perceptions of the CG associated with providing caregiving functions.

The CG has to balance a dual responsibility of looking after a disabled stroke survivor as well as making adjustments in his or her lifestyle. The needs of a stroke survivor vary from physical (walking, transfer from bed to chair, chair to toilet), communication (verbal and nonverbal with family members, friends), nursing (feeding, changing clothes, personal toilet), emotional and psychological changes to adapt to the consequences of stroke and financial (loss of employment, medical bills).

Because of its debilitating and chronic nature, caring for stroke patients often puts considerable burden on their CGs. It is therefore important to identify the factors affecting the CGs’ burden. The CG burden is perceived differently in the Indian context depending on the society and culture. In the Indian culture, men are the bread winners and head of the family and women generally look after the family wellbeing at home. Considering the chronic nature of stroke, tending to an elderly family member at home will undoubtedly place enormous burden on the female CGs. Recovery of a stroke patient is enhanced by a supportive environment and healthy CG. There is evidence to suggest that CG stress may impact the recovery and successful rehabilitation of stroke patients.[8]

Materials and Methods

The recently concluded Mumbai Stroke Registry provided the basic framework for the CG study.[9] We followed the WHO definition of Stroke as rapidly developing signs of focal disturbance of cerebral function lasting more than 24 h (unless interrupted by surgery or death) and of presumed vascular origin.[10] The definition included patients presenting with clinical signs and symptoms of subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, thrombosis and embolism. However, cases of transient ischemic attack, subdural hematoma and chronic cerebrovascular disease were not included. “First ever strokes” (FES) were defined as clinical stroke that occurred in patients without any prior stroke event. The manual on WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPS Stroke; http://www.who.int/chp/steps/Manual pdf) was operational protocol for terminologies and methodologies on evaluation, assessment and data management.

CGs’ primary demographic data, relationship with the patient, hours of care per day, educational qualifications, occupation, presence of additional CG, anxiety, depression and financial difficulties were obtained. Their level of stress was ascertained by two scales: Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale (OCBS) and the Caregivers Strain Index (CSI)[11] at 28 days after stroke and follow-up at 6 months and 1 year. The OCBS consists of 15 questions on tasks and activities to help the patient and the responses to each of them are graded from 1 to 5 (1 being least difficult and 5 being a great amount of difficulty). A score of 15–30 was considered mild stress, 31–45 was moderate stress and 46–60 was graded as severe stress. The CSI has a set of 13 questions. The CSI measures strain related to care provision. There is at least one item for each of the following major domains: Employment, financial, physical, social and time. Positive responses to seven or more items on the index indicate a greater level of strain.

Study population

We selected a well-defined community (H-ward) with verifiable census data[9] (2004) and representative of population structure (by gender and mid-decade age-bands) of Mumbai (Bombay). Of 3,61,295 permanent residents, 1,74,398 persons between the age of 25 and 95 years who were eligible for the survey were located by streets, buildings and colonies. The permanent residents here are predominantly Hindus (85%), Muslims, Christians and others (15%), and are mainly employed in private or public service sector or in business enterprises (there are no major industries or factories in this area). They belong to the middle or lower socioeconomic groups, and a majority reside as a joint family unit in one- or two-room apartments (less than 800 sq ft). In view of the lack of domestic facilities and economic hardships, any member of the family with a major or a serious illness is usually rushed to a public or semiprivate health-care facility; furthermore, medical insurance benefits are not available for domiciliary care. The population is served by one municipal general hospital, two private hospitals, four nursing homes and two computed tomography (CT) diagnostic centers.

Duration of the study

The pilot phase of the study comprised of the recruitment and training period of the Medico Social Worker specially appointed for the purpose, and lasted from 1st Oct 2008 to 31st Dec 2008. Data collection started from 1st Jan 2009 till 31st Dec 2009. Follow-up for 1 year of all patients and CGs was completed by 31st Dec 2010.

Study team

Along with the Principal Investigator, the specially trained team comprised of two research officers, 1 medico–social worker and secretarial staff, and neurologists and physicians of the area cooperated in the study. The team received intensive training on definitions/terminologies in respect to the questionnaire (STEPS Stroke version 2.0, OCBS and the CSI) and responses, including independent assessment of neurological deficit at onset and disability status at 28 days by Modified Rankin scale (MRS) and rechecked by a neurologist.

The CGs’ stress was assessed by OCBS and the CSI. The study team was trained to conduct interviews with CGs and assess their responses accordingly. Where information was not available, the response was listed as “missing values.”

Caregiver's stress evaluation

All cases of “FESs” from the study population (H-ward) were registered and their CGs’ were included in the study. The CGs’ were briefed on the purpose of the study and their consent was obtained. The CGs’ in the community were approached at a time of their convenience and, if necessary, multiple visits to the same site were made. The response of the CGs varied from being very cooperative to not being interested. The study team visited the CG and the patient at their homes with prior appointment and conducted face-to-face interviews. A recent study from Kolkata[12] reported burden among CGs from an urban population (both slum and nonslum areas).

Follow-up

The first CG visit was scheduled at 28 days after stroke. Subsequently, they were interviewed at the end of 6 months and 1 year.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out using “True Epistat (version:5)” on the following variables: Age, sex, the severity of stroke at onset, severe Barthel Index at 28 days (poor morbidity), long hours of care, disturbed night sleep, anxiety, financial adjustments, arranging for transport and substitute help and emotional and behavioral changes in the patient. Gender differences on the above variables were also assessed by Chi-square test and log likelihood ratio test.

Ethics committee approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the LKMM Trust Research Centre. Identity of stroke subjects and the CGs who volunteered for this study were not divulged; codes were assigned to each case.

Results

During the study period, 232 stroke patients were identified, of which 223 were “FESs” and were enrolled in the study. The age-adjusted incidence rate of stroke by SEGI was 137/100,000 population (95% CI 119–155). The mean age of patients was 67.5 years (SD±13.19), with a range from 26 to 101 years. Before the onset of stroke, 78% of the cases had hypertension, 42% had diabetes mellitus, 18.3% had ischemic heart disease, 21.9% had raised cholesterol and 24.6% had a history of smoking. One hundred and thirty-five (60.5%) patients were hospitalized, 56 (25.1%) were admitted to nursing homes and 32 (14.3%) were cared for at home. At 28 days, 127 (56.9%) were alive, 79 (35%) died and 17 were lost to follow-up. At 28 days, 47 (21%) had mild disability and 80 (35.8%) were left with moderate to severe disability by the MRS. Of 79 deaths at 28 days, 49 (21.9%) were stroke deaths and 30 (13.4%) were nonstroke deaths due to comorbid conditions.

Of 127 patients alive at 28 days, nine were independent requiring no CG help and seven did not agree to participate; hence, 111 CGs were enrolled in the study. Data was entered in the master spreadsheet and analyzed. Of 111 CGs, 89 (80%) were women and 22 (20%) were men. The age of primary CG ranged from 20 to 81 years. Mean age of female CG was 44.8 years (±14.3) and mean age of male CGs was 48.7 years (±19.0). Mean age of CGs was 20 years younger than that of the patients. As for relationship to the patient, 41 (37%) were spouse, 28 (25.2%) were children, 28 (25.2%) were daughter-in-laws and only one was (0.9%) son-in-law, 12 (10.8%) were relatives (sibling, aunt, uncle and extended family members) and one (0.9%) was a maid. None of the CGs in the study had received any formal training in caregiving.

Factors affecting CG burden

Patient characteristics

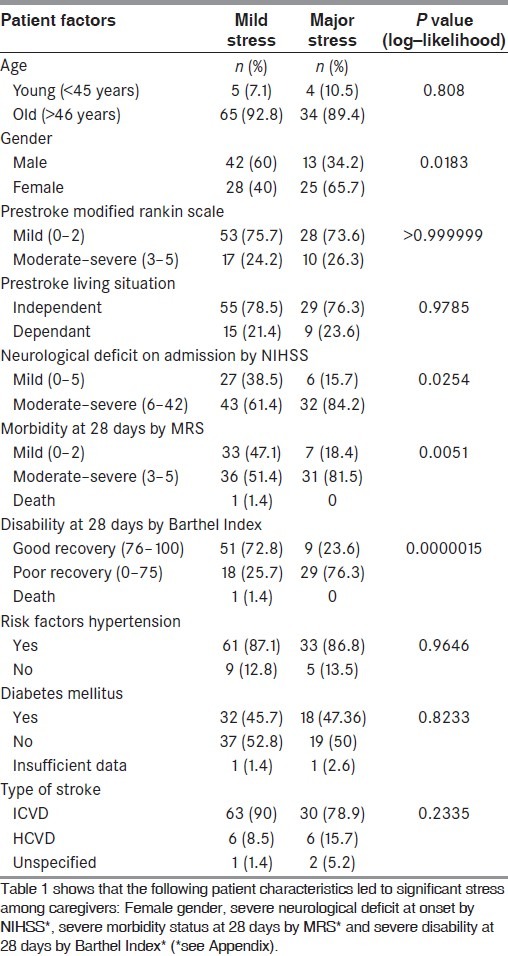

As shown in Table 1, patient factors leading to increased caregiving burden included patient being female (P=0.0183), moderate to severe neurological deficit by NIHSS scale on admission (P=0.0254), morbidity at 28 days by MRS (P=0.0051) and poor recovery at 28 days with Barthel Index score of less than 50 (P=0.0000015) [Figure 1]. However, patient's age, type of stroke, presence of risk factors like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, raised cholesterol; ischemic heart disease, etc. were not related to increased CG burden.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics responsible for major caregiver stress

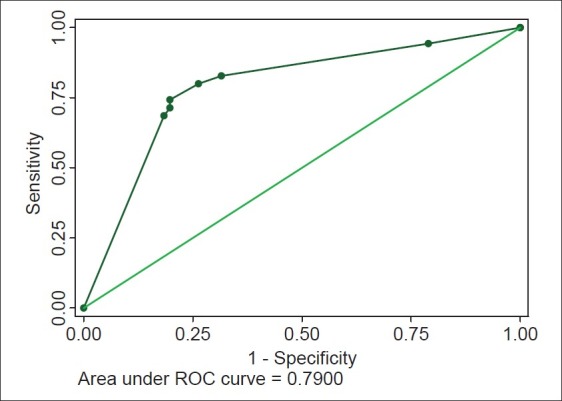

Figure 1.

Receiver–operating characteristic (ROC) curve for patient factors responsible for significant caregiving stress. NIHSS at 28 days and Barthel Index at 28 days contribute significantly to caregiver stress. ROC covers 79% of the area; sensitivity is low (69%) although specificity is significant (82%)

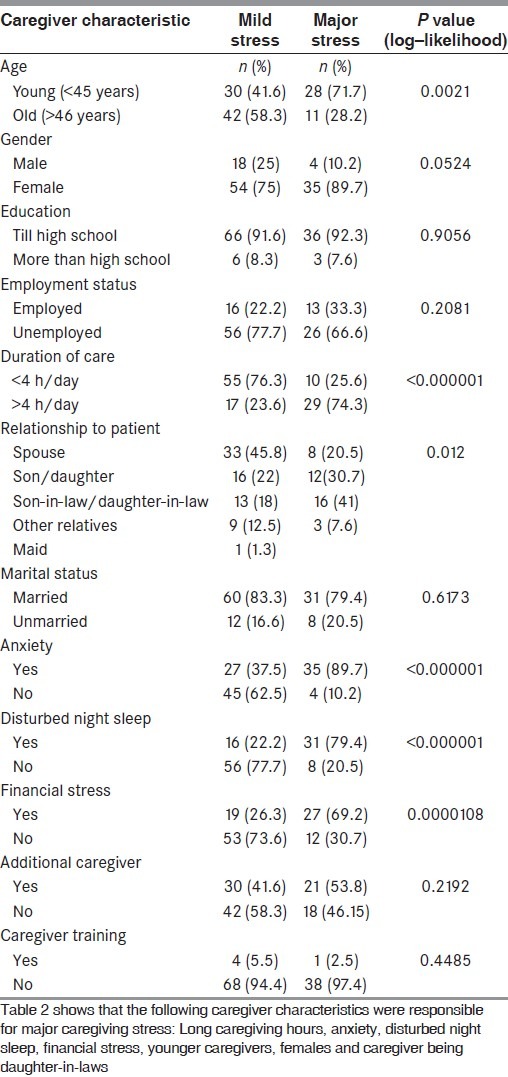

CG factors

CG factors that were related with high caregiving stress (both by RSS and CSI scales) were: (i) younger age (<45 years), (ii) female gender, (iii) long caregiving hours (on an average 8.4 h per day), (iv) CGs being daughter-in-laws faced major stress, whereas spouse CGs had minor stress, (v) anxiety, (vi) disturbed night sleep and (vii) financial stress [Table 2 and Figure 2]. All these factors consistently showed higher caregiving burden at 28 days, at 6 months and at 1 year following stroke (except for CG gender, which was not significant at 6 months and at 1 year). On the other hand, education, employment status, marital status and presence of additional CG was not related to significant CG stress.

Table 2.

Caregiver factors responsible for major stress

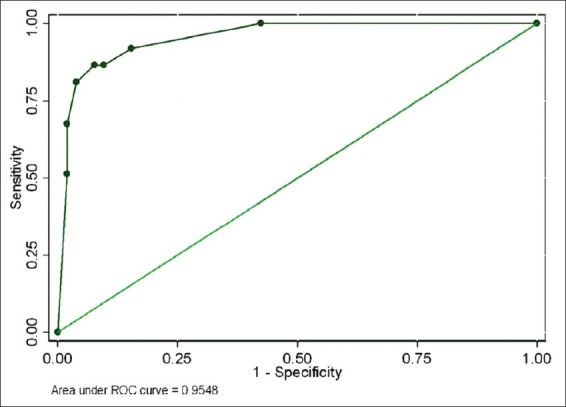

Figure 2.

Receiver–operating characteristic (ROC) curve for caregiver factors responsible for major stress. The model based on three risk factors – inconvenience, demands on time, financial stress – at 1 month does quite well for predicting caregiver stress at 1 month. The area under the ROC curve is 95%, sensitivity is 86% and specificity is 92%. The odds ratio and regression coefficient are highest for inconvenience (OR 23.42), intermediate for demands on time (OR 13.54) and lowest for financial stress (OR 5.12) – all being statistically significant

CG burden assessment

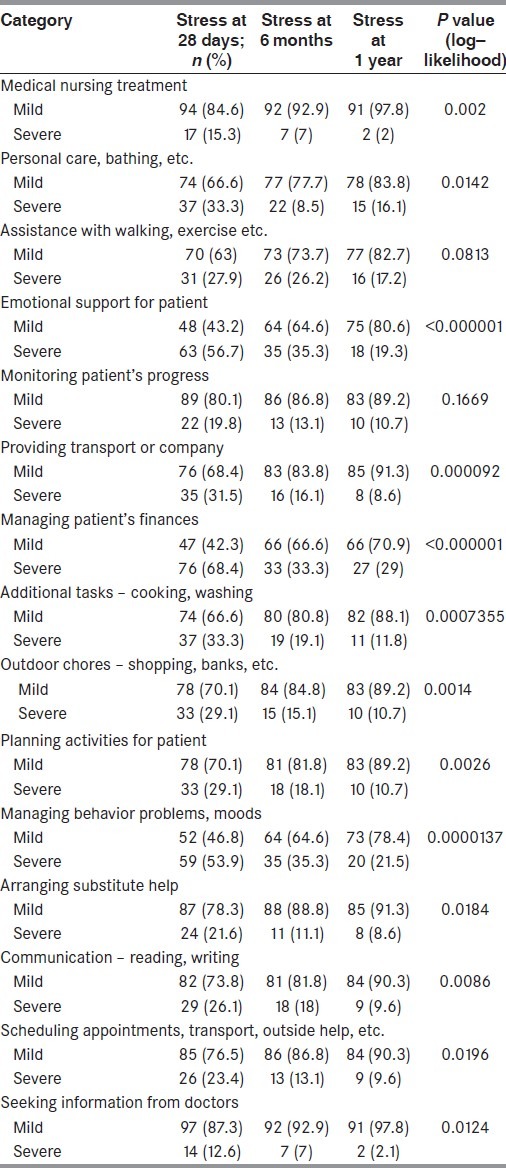

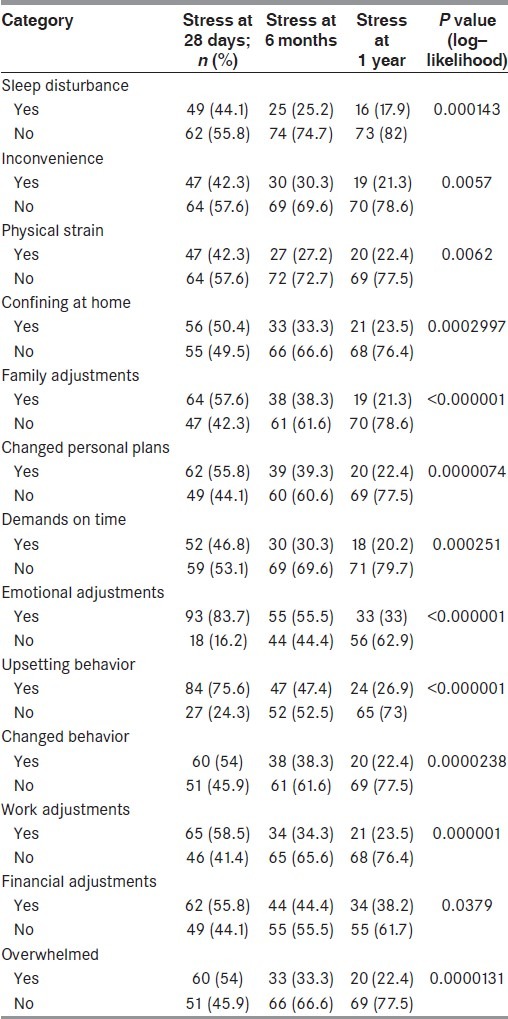

The CG burden was assessed by two instruments: The OCBS and the CSI. The OCBS was helpful in identifying the level of difficulty in performing tasks and activities for the patient. Data analysis showed that tasks like medical and nursing care (P=0.002), emotional support to the patient (P≤0.000001), providing company and arranging transport (P=0.000092), managing patient's finances (P≤0.000001), tasks like cooking, washing clothes (P=0.00073), managing behavior problems (P=0.000013), daily communication like reading, writing (P=0.008) and planning daily activities for the patient (P=0.0026) gave rise to higher scores and higher burden [Table 3]. The CSI measures the strain resulting from care provision, and data analysis showed that all the major domains like employment adjustments (P=0.000001), financial difficulties (P=0.03), physical strain (P=0.0062), social adjustments (0.000001) and demands on time (P=0.00025) led to higher increased caregiving strain [Table 4].

Table 3.

Caregiver factors leading to stress by Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale (OCBS)* (see Appendix)

Table 4.

Caregiver factors leading to stress by Caregiver Strain Index (CSI)* (see Appendix)

Follow-up assessments at 6 months and at 1 year following stroke revealed that most of the above-mentioned factors were responsible for higher stress consistently, although the overall/total burden scores were high immediately following stroke at 28 days and improved at the end of 1 year post stroke. It could be explained by the fact that over a period of time, the CG adapts and accepts his/her new role as a provider.[13] In Asian countries including India, parents and elderly family members are respected and, in case of illness, are usually cared for by immediate family members like offsprings and daughter-in-law.[14]

Discussion

India is a developing economy, where ageing population, changes in lifestyle and rapid urbanization have contributed to a rise in noncommunicable diseases, including stroke.[15] A recent population-based study has confirmed the burden of stroke in the ageing population. The overall age-adjusted rate for FESs was 152/100,000 persons and, for persons above the age of 55 years, it was 424/100,000 persons, which is nearly the same as that prevailing in developed countries.[9]

At the moment, nearly one-third of the stroke survivors stay at home and take domiciliary care, which in reality is a burden on the CG. In oriental countries including India, the joint family system prevails, wherein in a small apartment (less than 800 sq. ft), parents, spouse, children (son and daughter-in-law) stay together sharing infrastructural facilities. Therefore, any patient with a major illness like stroke is preferable sent to a nearby health care facility, but this may not always be possible on account of economic constraints, deficient infrastructure facilities, etc.

Stroke morbidity and mortality has assumed alarming proportions in low- and middle-income countries. This burden predominantly affects the low- and middle-income countries. In the year 2005, India accounted for more than 53% of all deaths from and 44% of DALYs lost from chronic diseases (including stroke).[16,17]

The study showed that CGs of stroke survivors face a significant amount of stress at all times. For all CGs’ in the study, this was their first experience. It highlights the financial, emotional, physical and mental anxiety faced by stroke CGs and the influence of family bonding and social customs. Eighty percent of the CGs were women and majority of the patients were cared for by immediate family members like spouse, son/daughter, son-in-law, daughter-in-law, siblings, etc.[12,18] The family members had to adjust their work schedule while many had to give up their jobs. Younger CGs and daughter-in-laws faced major stress, whereas spouse CGs had relatively mild stress.

In the Indian culture, the joint family system ensures that every member of the family helps in caregiving, e.g. spouse, in-laws in physical management, men in organizing medication and finances, children in improving the environment and even neighbors and relatives help in looking after chores.[12] This is in contrast to the western culture, and is a boon in disguise. Similar observations have been reported from Korea and India.[12,19] Curiously, education and employment status of the CGs was not associated with higher stress in our study, in contrast to the study from Korea,[19] whereas duration of care (>4 h of caregiving per day), anxiety, disturbed night sleep and financial stress were factors giving rise to severe stress. Unlike other studies,[20,21] our study showed that morbidity of the patient (severe MRS score of 3–5) was a major factor leading to higher caregiving stress.

Predischarge training of the CG in activities of daily living (moving, handling, transferring patient from bed to chair, chair to toilet), nursing activities (feeding), communication (verbal and nonverbal) interaction with family, friends and society for social reintegration are essential and will reduce the anxiety stress of CG and improve the quality of life of the stroke survivor.[13,22,23] Therefore, the CG needs to be motivated, should be in good physical health and emotionally sound, financially resourceful and adequately trained. This will reduce the CG stress. In our environment in India, there is no organized training at the nurses’ station or interaction with social worker or treating physician directly or telephonically, and this results in confusion in management. In reality, there is hardly any time between sudden onset of stroke and discharge from hospital to acquire training attitudes.

Conclusions/Recommendations

The rising burden of stroke globally both in developed and developing nations will eventually increase the burden on CGs. The limited help from NGOs is not sufficient to take care of the social load. Our study shows that financial worries, long caregiving hours and emotional stress are predominant factors increasing CG stress. Stroke rehabilitation services should also address CG issues and include practical training in nursing skills and counseling sessions, which will help in reducing the CG burden and improve patient recovery.[13,22,23] Planned studies of CG stress vis-a-vis stroke burden with defined protocol at multiple centers need to be studied to arrive at some general planning as well as to identify the local situation.

Appendix

-

1)

MRS: Modified Rankin Scale measures independence rather than performance of specific tasks. Scale consists of six grades from 0 to 5; 0 denotes no symptoms and 5 indicates severe disability. For clinical purpose, mild disability range is from 0 to 2; moderate disability ranges from 3 to 4 and 5 indicates severe disability. Prestroke MRS evaluation defines the level of disability a person already has before the onset of stroke. It acts as a reference point to assess the degree of recovery poststroke in a patient.

-

2)

NIHSS: It is a scoring technique that defines the degree of neurological deficit, ranging from none (0), mild (1) or severe (2–4) for 11 categories of neurological functions. For practical purposes, a score of 0–5 indicates mild deficit, 6–15 denotes moderate deficit and score of more than 15 is suggestive of severe neurological deficit.

-

3)

Barthel Index: It is a scoring technique that measures patient's performance in 10 activities of daily life, and it is considered a reliable disability scale for stroke patients. For clinical evaluation, 76–100 points denote “good function,” 51–75 points denote “moderate disability” and score under 50 denotes “severe disability.” 0 score represents totally dependent bedridden state.

-

4)

Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale consists of 15 questions on tasks and activities to help the patient, and the responses to each of them are graded from 1 to 5 (1 being least difficult and 5 great amount of difficulty). A score of 15–30 was considered mild stress, 31–45 was moderate stress and 46–60 was graded as severe stress.

-

5)

Caregivers Strain Index has a set of 13 questions. The CSI measures strain related to care provision. There is at least one item for each of the following major domains: Employment, financial, physical, social and time. Positive responses to seven or more items on the index indicate a greater level of strain.

Acknowledgments

Dr. A. Nanivadekar Consultant Biostatistician, for statistical guidance

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

References

- 1.Choi-Kwon S, Mitchell PH, Veith R, Teri L, Buzaitis A, Cain KC, et al. Comparing perceived burden for Korean and American informal caregivers of stroke survivors. Rehabil Nurs. 2009;34:141–50. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2009.tb00270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1269–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strong K, Mathers C, Bonita R. Preventing stroke: Saving lives around the world. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:182–7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparing Stroke Incidence Worldwide-what makes studies comparable? Stroke. 1996;27:550–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hileman JW, Lackey NR, Hassanein RS. Identifying the needs of home caregivers of patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1992;19:771–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach–Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–55. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberst MT. Perspective on Research in Patient Teaching. Nurs Clin North Am. 1989;24:621–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigby H, Gubitz G, Eskes G, Reidy Y, Christian C, Grover V, et al. Caring for stroke survivors: Baseline and 1-year determinants of caregiver burden. Int J Stroke. 2009;4:152–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalal PM, Malik S, Bhattacharjee M, Trivedi ND, Vairale J, Bhat P, et al. Population based stroke survey in Mumbai, India: Incidence and 28-day case fatality. Neuroepidemiolgy. 2008;31:254–61. doi: 10.1159/000165364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aho K, Harmsen P, Hatano S, Marquardsen J, Smirnov VE, Strasser T. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: Results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ. 1980;58:113–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson BC. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J Gerontol. 1983;38:344–8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das S, Hazra A, Ray BK, Ghosal M, Banerjee TK, Roy T, et al. Burden among stroke caregivers-results of a community based study from Kolkata, India. Stroke. 2010;41:2965–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCullagh E, Brigstocke G, Donaldson N, Kalra L. Determinants of caregiving burden and quality of life in caregivers of stroke patients. Stroke. 2005;36:2181–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000181755.23914.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon SC, Kim HS, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Factors affecting the burden on caregivers of stroke survivors in South Korea. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1043–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalal PM, Bhattacharjee M, Vairale J, Bhat P. UN millennium development goals: Can we halt stroke epidemic in India? Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2007;10:130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy KS, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366:1744–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalal PM, Bhattacharjee M. “Handbook of Disease Burden and Quality of Life Measures”. Germany: Springer Verlag Publications; 2010. Burden of Stroke: Indian Perspective; pp. 992–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morimoto T, Schreiner AS, Asano H. Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life among Japanese stroke caregivers. Age Ageing. 2003;32:218–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon SC, Kim HS, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Factors affecting the burden on caregivers of stroke survivors in South Korea. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;36:1043–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson CS, Linto J, Stewart-Wynne EG. A population based assessment of the impact and burden of caregiving for long term stroke survivors. Stroke. 1995;26:843–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park KA, Kim HS, Kim JS, Kwon SU, Kwon SC. Food intake, frequency and compliance in stroke patients. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2001;6:542–52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankey G. Informal caregiving for disabled stroke survivors. BMJ. 2004;328:1085–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7448.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalra L, Evans A, Perez I, Melbourn A, Patel A, Knapp M, Donaldson N. Training care givers of stroke patients: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328:1099–101. [Google Scholar]