Abstract

Background:

There is a lack of knowledge about epilepsy among the students and the population in general, with consequent prejudice and discrimination toward epileptic patients.

Objectives:

Knowledge, behavior, attitude and myth toward epilepsy among urban school children in Bareilly district was studied.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among students of 10 randomly selected secondary schools of the urban areas in Bareilly district. A structured, pretested questionnaire was used to collect data regarding sociodemographic characteristics and assess the subject's knowledge, behavior, attitude and myth toward epilepsy.

Results:

Of the 798 students (533 boys and 265 girls) studied, around 98.6% had heard of epilepsy. About 63.7% correctly thought that epilepsy is a brain disorder while 81.8% believed it to be a psychiatric disorder. Other prevalent misconceptions were that epilepsy is an inherited disorder (71.55%) and that the disease is transmitted by eating a nonvegetarian diet (49%). Most of them thought that epilepsy can be cured (69.3) and that an epileptic patient needs lifelong treatment (77.2). On witnessing a seizure, about 51.5% of the students would take the person to the hospital. Majority (72.31%) of the students thought that children with epilepsy should study in a special school.

Conclusions:

Although majority of the students had reasonable knowledge of epilepsy, myths and superstitions about the condition still prevail in a significant proportion of the urban school children. It may be worthwhile including awareness programs about epilepsy in school education to dispel misconceptions about epilepsy.

Keywords: Attitude, behavior, epilepsy, knowledge, myth, students

Introduction

Epilepsy is a neurological condition characterized by recurrent seizures without toxic–metabolic or febrile causes. As in other chronic conditions, epilepsy has emotional and social health implications in addition to its physical effects, requiring those with epilepsy to adapt to social environments and to deal with emotional difficulties.[1,2]

Although knowledge, attitude and beliefs toward epilepsy have improved in most countries, there is still misperception about the disorder. Living in the society is more challenging than epilepsy itself.[3] Fear and misunderstanding of epilepsy may lead to social stigma, resulting in social discrimination, particularly in teenagers.[4] Thus, lack of information has been indicated as an important factor in stigma perpetuation.[5] Interestingly, surveys in developing countries[6,7] with different cultures reveal common beliefs, e.g. that epilepsy is a contagious illness or a kind of mental retardation.[8] In addition, some people do not know what to do with a person during an epileptic seizure, which promotes a feeling of impotence and reinforces the misconception that epilepsy has no treatment.[9,10] With this background, the present study was conducted among secondary school children of urban Bareilly with the following aims and objectives:

To assess their knowledge, behavior and attitude toward epilepsy.

To improve their knowledge of epilepsy.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional survey was conducted in April 2010 in 10 randomly selected secondary schools of urban areas of a total of 30 schools in the Bareilly district of Uttar Pradesh. A structured, pretested questionnaire consisting of close-ended questions was used to collect data regarding the sociodemographic characteristics and assess the knowledge, behavior, attitude and myth of the students toward epilepsy. The questionnaire was derived from literature reviews using multiple types of references and few questions related to the prevalent local belief were added. The language used in the questionnaire was English. All the students of class ninth and tenth in the selected schools were asked to fill the questionnaires individually at the same time in the classroom. The response rate of students was 100%. The questions were read by the researcher, and the students wrote their answers in yes or no without consulting each other or any other source. The process took about 20 min. After this survey, the researcher carried out educational activities with these children to improve their knowledge of epilepsy. Socioeconomic status among the students was measured using the Modified Prasad's classification.[11]

Written consent was obtained from the principals of the respective schools after explaining to them the purpose of the study. The study was started after ethical clearance from the institution review board in February 2010. Data entry and statistical analysis were performed using the Microsoft Excel version 2007 and Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) windows version 14.0 software. Responses of students in “Yes” or “No” were given as percentages.

Results

Sociodemographic profile

A total of 798 (422 class ninth and 376 class tenth) secondary school children participated in the study. There were 533 boys (66.8%) and 265 girls (33.2%). Four hundred and fourteen (51.8%) were Hindus, 271 (33.96%) were Muslims, 79 (9.9%) Sikhs and 34 (4.26%) belonged to other communities. Five hundred and forty-three (68.05%) students belonged to the middle socioeconomic class, 164 (20.55%) to high class and 91 (11.4%) to low class as per the Modified Prasad's classification.

Knowledge

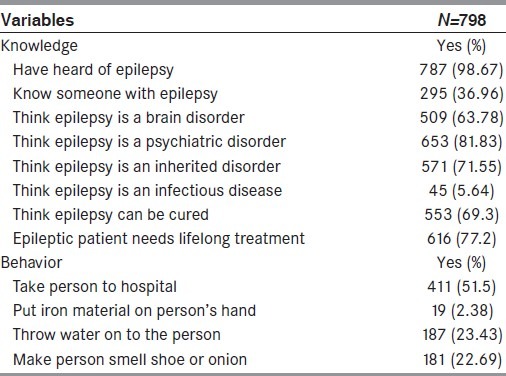

Around 98.6% of the children had heard of epilepsy. About 36.9% knew of at least one person with epilepsy. Five hundred and nine students (63.7%) correctly thought that epilepsy is a brain disorder while 81.8% believed epilepsy to be a psychiatric disorder. Majority of the students (71.55%) thought that epilepsy is an inherited disorder, while 5.64% believed that epilepsy is an infectious disease. A higher proportion of respondents thought that epilepsy can be cured (69.3) and that an epileptic patient needs lifelong treatment (77.2) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Knowledge and behavior of secondary school children regarding epilepsy

Behavior

On witnessing a person with seizure, about 51.5% of the students would take the person to the hospital, while 23.43% would throw water on to the person and 22.69% would make the person smell a shoe or an onion [Table 1].

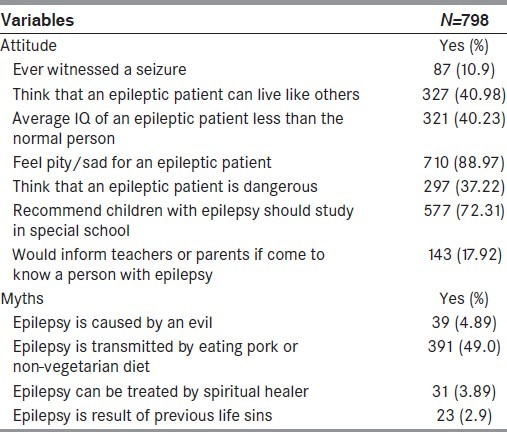

Attitude

Only 10.9% of the students had ever witnessed a seizure. Around 40.98% thought that an epileptic patient can live like others, while 40.23% believed that an average IQ of an epileptic patient is less than a normal person. Most (88.97%) of the students felt pity/sad for an epileptic patient, and 37.22% of them thought that an epileptic patient is dangerous. Majority (72.31%) of the respondents thought that children with epilepsy should study in a special school. About 17.92% of the students would inform the teachers or parents if they come to know a person with epilepsy [Table 2].

Table 2.

Attitude and myths of secondary school children regarding epilepsy

Myths

Forty-nine percent of the students had a false notion that the disease is transmitted by eating non-vegetarian diet. Other myths found to be prevalent were that epilepsy is caused by an evil (4.89) and that the disease can be treated by a spiritual healer (3.89) [Table 2].

Discussion

The current study revealed that majority (98.6%) of the children had heard of epilepsy, which is similar to the trends reported in other studies conducted among school students in different parts of India.[10,12,13] The prevalent misconceptions among our study participants were that epilepsy is an inherited disorder or a psychiatric disorder. This is in agreement with previous studies.[10,12,13] Nearly two-third of the respondents thought that epilepsy can be cured and three-fourth thought that an epileptic patient needs lifelong treatment in this study. Similar trends have been reported in the Uttarakhand study.[13] Our study revealed that about half of the students would take a person with an acute attack of epilepsy to the hospital while nearly one-fifth would throw water on to the person or would make the person smell a shoe or an onion. This is again similar to the observations reported by Goel et al., where about 40.8% students believed that the acute attack of epilepsy could be terminated by the smell of an onion or a shoe.[13]

Our study confirms gaps in knowledge and a negative attitude about various aspects of epilepsy, which is in agreement with the studies conducted among the elementary school children by Fernandes et al.[9] and among the Brazil university students by Tedrus et al.[14] Information campaigns should target the young age groups as the misperceptions are prevalent in them, as is the opportunity to change them. Destigmatization campaigns should be provided to correct students’ information and degrees of stigma toward people with epilepsy and provide appropriate education.[15] This, however, will require continuous and repetitive educational efforts in elementary schools. The core source of knowledge and attitudes in school children is parents and teachers.[16] It is important to impart in parents and school teachers awareness and knowledge regarding epilepsy as they play the key role in providing the correct information to the students. Surveys conducted among the schoolteachers in Indonesia and Sudan has shown that a significant proportion of them had a negative attitude toward and considerable misunderstanding of epilepsy.[17,18] It has been indicated that lack of knowledge about causes of epilepsy is the main factor affecting participants’ attitudes.[19] A larger and comprehensive community-based educational programme involving parents and children, perhaps using mass media, is very essential to bring about a change in the negative attitude toward epilepsy.

Although familiarity with epilepsy was high among high school students in Uttar Pradesh, misconceptions and negative attitudes were alarmingly high. Persistent and effective information campaigns, therefore, are necessary to change their attitudes toward fellow students with epilepsy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

References

- 1.Li LM, Sander JW. National demonstration project on epilepsy in Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61:153–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meinardi H, Scott RA, Reis R, Sander JW. The treatment gap in epilepsia: The current situation and way forwards. Epilepsia. 2001;42:136–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.32800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin JK, Shafer PO, Deering JB. Epilepsy familiarity, knowledge, and perceptions of stigma: Report from a survey of adolescents in the general population. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3:368–75. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bener A, al-Marzooqi FH, Sztriha L. Public awareness and attitudes towards epilepsy in the United Arab Emirates. Seizure. 1998;7:219–22. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(98)80039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker GA. People with epilepsy: What do they know and understand, and how does this contribute to their perceived level of stigma? Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiIorio C, Osborne SP, Letz R, Henry T, Schomer DL, Yeager K. The association of stigma with self-management and perceptions of health care among adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:259–67. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(03)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacoby A. Stigma, epilepsy, and quality of life. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3:10–20. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker GA, Jacoby A, Buck D, Stalgis C, Monnet D. Quality of life of people with epilepsy: A European study. Epilepsia. 1997;38:353–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandes PT, Cabral P, Araujo U, Noronha AA, Li LM. Kids perception about epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:601–3. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandian JD, Santosh D, Kumar TS, Sarma PS, Radhakrishnan K. High school students knowledge, attitude, and practice with respect to epilepsy in Kerala, southern India. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9:492–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal AK. Social classification: The need to update in the present scenario. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:50–1. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.39245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gourie Devi M, Singh V, Bala K. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice among patients of epilepsy attending tertiary hospital in Delhi, India and review of Indian studies. Neurol Asia J. 2010;15:225–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goel D, Dhanai JS, Agarwal AK, Mehlotra V, Saxena V. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of epilepsy in Uttarakhand, India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14:116–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.82799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tedrus GM, Fonseca LC, Vieira AL. Knowledge and attitudes towards epilepsy amongst students in the health area. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65:1181–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2007000700017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reno BA, Fernandes PT, Bell GS, Sander JW, Li LM. A study with secondary school students. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65:49–54. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2007001000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharya AK, Saha SK, Roy SK. Epilepsy awareness among parents of school children- a municipal survey. J Indian Med Assoc. 2007;105:243–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rambe AS, Sjahrir H. Awareness, attitudes and understanding towards epilepsy among school teachers in Medan, Indonesia. Neurol J Southeast Asia. 2002;7:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babikar HE, Abbas IM. Knowledge, practice and attitude toward epilepsy among primary and secondary school teachers in south Gezira locality, Gezira state, Sudan. J Fam Community Med. 2011;18:17–21. doi: 10.4103/1319-1683.78633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saengsuwan J, Boonyaleepan S, Srijakkot J, Sawanyawisuth K, Tiamkao S, Auevitchayapat N. Public perception of epilepsy: A survey from the rural population in Northeastern Thailand. J Neurosci Behav Health. 2009;1:6–11. [Google Scholar]