Abstract

Background

In Thailand, risk factors associated with suicide attempts in bipolar disorder (BD) are rarely investigated, nor has a specific risk-scoring scheme to assist in the identification of BD patients at risk for attempting suicide been proposed.

Objective

To develop a simple risk-scoring scheme to identify patients with BD who may be at risk for attempting suicide.

Methods

Medical files of 489 patients diagnosed with BD at Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital between October 2006 and May 2009 were reviewed. Cases included BD patients hospitalized due to attempted suicide (n = 58), and seven controls were selected (per suicide case) among BD in- and out-patients who did not attempt suicide, with patients being visited the same day or within 1 week of case study (n = 431). Broad sociodemographic and clinical factors were gathered and analyzed using multivariate logistic regression, to obtain a set of risk factors. Scores for each indicator were weighted, assigned, and summed to create a total risk score, which was divided into low, moderate, and high-risk suicide attempt groups.

Results

Six statistically significant indicators associated with suicide attempts were included in the risk-scoring scheme: depression, psychotic symptom(s), number of previous suicide attempts, stressful life event(s), medication adherence, and BD treatment years. A total risk score (possible range −1.5 to 11.5) explained an 88.6% probability of suicide attempts based on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Likelihood ratios of suicide attempts with low risk scores (below 2.5), moderate risk scores (2.5–8.0), and high risk scores (above 8.0) were 0.11 (95% CI 0.04–0.32), 1.72 (95% CI 1.41–2.10), and 19.0 (95% CI 6.17–58.16), respectively.

Conclusion

The proposed risk-scoring scheme is BD-specific, comprising six key indicators for simple, routine assessment and classification of patients to three risk groups. Further validation is required before adopting this scheme in other clinical settings.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, mood disorders, suicidal behavior, screening tool

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) has been documented as producing the highest rate of suicidal behaviors compared to any other psychiatric disorder.1 Over their lifetime, some 61% of BD patients will experience suicidal ideation2, 25% to 56% will attempt suicide, and 10%–19% will die from suicide.3, 4 Several studies suggest that BD patients’ previous suicide attempt(s) may indicate that they are more than 50% more likely to go on to complete suicide.5,6 A better understanding of the characteristics and risk factors related to suicide attempts is the first step in preventing future attempts and early detection of at-risk patients.

The upper northern region of Thailand, where the present study was conducted, comprises eight provinces and is recognized as having the highest rate of suicide in the nation: 13.1 compared to 5.9 per 100,000 nationally in 2010.7 Seven provinces were ranked in the top ten for the highest rate of completed suicide (9.45 to 20.02 per 100,000). The rate of suicide attempts in this particular area is also remarkably high, at 34.4 per 100,000. BD consistently ranks among the top ten high-burden psychiatric diseases at Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital, the largest referral psychiatric hospital in the region. BD is ranked third at 7.5% and fourth at 6.4% for inpatients and outpatients respectively, which at 23.7% accounts for almost a quarter of patients with mood disorders being hospitalized due to attempted suicide.8

Over the years, there has been increasing awareness of the need to identify those at high risk for suicide attempts, including BD patients, at every level of health care. However, the rate of suicide attempts among patients with BD has not decreased. Some screening tools for suicide risk have been used at the primary and secondary care level, where psychiatrists are rarely involved. These typically include generic tools comprising items examining suicidal thoughts, plans and past attempts, assessed by a nurse-administered, face-to-face structured interview. To specifically identify patients with BD who are at risk of suicide attempts, a risk- scoring scheme derived from factors associated with suicide attempts (ie, demographic and clinical factors) should be developed.

The current study proposes a risk-scoring scheme for suicide attempts in Thai patients with BD. This scheme might help health care providers identify patients with BD who are at risk of attempted suicide. First, we explored factors associated with suicide attempts in BD, including gender,9,10 younger age at admission,9,11,12 extent of depressive or mixed polarity,9–13 increasing severity of affective episodes,11 multiple hospitalizations,9,10 comorbid Axis I disorders,11 abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs,11 previous suicide attempt(s),9,12 previous suicidal ideation,10 family history of suicide,11 stressful life events before onset of illness,9 administration of lithium prophylaxis,14 and benzodiazepine use.15 A simple risk-scoring scheme was then developed and assessed for its ability to identify patients with BD who might be at risk for attempted suicide.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital. This is the largest tertiary psychiatric hospital in Chiang Mai, with a capacity of 700 beds, and has served patients in the upper northern region of Thailand since 1938. The hospital provides medical care to approximately 60,000 outpatients and 7,000 inpatients each year.16

Study population

Eligible subjects were patients diagnosed with BD by psychiatrists, and coded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10); ICD-10 F31.X.17 Cases were all patients with BD hospitalized due to suicide attempts irrespective of the number of attempt(s) (n = 58). Seven controls per case were selected from the BD inpatient and outpatients who did not attempt suicide, visiting on the same day or within one week of case study (n = 431). Date of visit was set as an index date. Controls were selected from the hospital database.

Data collection

Medical files were reviewed and extracted by five nursing staff who were unaware of the study questions. The research team held two meetings prior to data collection to standardize data collectors by discussion and clarification of each variable.

Potential sociodemographic and clinical factors were selected and categorized based on literature review and opinions of the psychiatric study team. Sociodemographic factors included gender, age, marital status, educational level, occupation, religion, living status (alone or with others), number of children, and stressful life event(s) (ie, interpersonal relationship problems, loss of loved ones, and economic crisis prior to, or at, the index date). Social support was classified into “excellent”, “good”, “moderate”, and “little or very little” categories.

Clinical factors related to signs and symptoms at the index date included depressive episodes, manic/mixed episodes, and psychosis as assessed by the attending psychiatrist using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10). Duration of BD treatment was defined as the beginning of BD treatment to the index date. Age at onset was the age of BD diagnosis. Previous admission was confined only to Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital for any reason prior to the index date. Previous suicide attempt(s) were assessed and quantified, as well as suicidal ideation (yes/no), before the index date. Psychotic symptoms at index episodes were hallucinations, hearing voices, and other psychotic symptoms. Psychiatric comorbidity was extracted from the ICD-10 code and grouped into alcohol/substance dependence, which has been commonly observed in other disorders. Somatic illness included any chronic disease. Past and current smoking, alcohol use, and any other substance abuse were recorded.

Type(s) of prescribed medication(s) were categorized mainly by their mechanism(s) of action and grouping in previous studies regarding suicide attempts. Mood stabilizers were categorized as either lithium or others, such as carbamazepine and valproate. Antidepressants were grouped as norepinephrine (NE) and/or serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, venlafaxine, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine. Antipsychotics were divided into typical and atypical agents, typical being zuclopenthixol and haloperidol, and atypical being clozapine and risperidone. Anxiolytics consisted of benzodiazepine and others. An attending pharmacist, asking patients or their relatives, assessed medication adherence, which was summarized as “good or excellent,” meaning that patients always took their medication or rarely missed a dose; “intermittent or poor adherence,” meaning that patients took their medication sporadically, or that there was at least one consecutive week where the patient did not take their medication. Other factors included family history of mental disorders, family history of attempted or completed suicide, and method(s) used for suicide attempts.

Two Institutional Review Boards – The Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, and Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital – approved the study protocol.

Statistical analyses

Two steps of data analyses were performed. In the first step, each factor was explored, and statistical differences between suicide attempters and nonattempters, using univariate logistic regression, were assessed. Continuous variables such as duration of treatment and number of previous suicide attempts were categorized according to clinical significance and effects (odds ratios) from statistical significance. Potential indicators containing P values of below 0.05 were selected for the next analysis step. In the second step, the last model with factors that reached statistical significance was determined using a multivariate stepwise logistic regression approach. Missing values of risk indicators were handled by a multiple imputation method (MI). Coefficients from each variable were weighted, transformed to item scores, and summed up to a total score. The relative operating characteristic (ROC) plot assessed the probability of a total score indicating suicide attempts. Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test was performed for correspondence between the estimated risk from logistic estimation and the actual risk of each total score. The positive likelihood ratio (LHR+) was calculated from the total score, which was categorized into low, moderate, and high risk by selected cut-off points. The cut-off points were determined by the probability of suicide attempts. The LHR+ of <0.1 times in the low risk group and >10 times in the high risk group indicates a clear distinction between increasing and decreasing probability of suicide attempts, respectively.18

Statistical significance was set at 0.05 to minimize Type I error.

Sample size estimation was based on ratio of suicide attempts to non-attempts among BD patients, using various factors from previous studies such as history of suicide attempts, depressive phase, early age at onset, and duration of illness. The least differential proportion among these variables was early age at onset, at 52% and 27% in suicide attempters and non-attempters, respectively.12 Since 58 admissions of suicide attempts were obtained from BD patients during the course of the study, the required number of controls was calculated. To ensure a power of 80% and a 0.05 Type I error rate, 7 controls per case (or a total of 406 patients) were needed.

Results

A total of 489 patients’ medical files were reviewed and included in the final analysis. Of those, 58 (11.9%) admitted attempting suicide. Among suicide attempters, 39 (68.4%) used one method, 11 (19.3%) and 4 (7.1%) used two and more than two methods, respectively. Four patients had missing data for the method used. Drug overdose was the most commonly used method in 17 (29.8%) patients, followed by hanging for 15 (26.3%), cutting with a knife or sharp object for 12 (21.4%), jumping from a high place for 7 (12.3%), ingesting pesticide for 6 (10.3%), jumping in front of moving vehicle for 4 (7.0%), and jumping in water for 2 (3.5%) patients.

Results from the univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that suicide attempters were younger, single, did not have children, and had little or very little social support. They reported experiencing more stressful life events, reported being depressed, had suffered from BD at an early age, had a family history of suicide, had previously attempted suicide, had previous suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and were prescribed antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and mood stabilizers. Meanwhile, psychotic symptoms and increasing years of BD treatment decreased the probability of suicide attempts (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic factors of patients with BD classified by suicide attempts

| Sociodemographic factors | Suicide attempts | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 58) | No (n = 431) | ||

| Gender | 0.685 | ||

| Female | 35 (60.3) | 248 (57.5) | |

| Male | 23 (39.7) | 183 (42.5) | |

| Age (years) | 30.5 ± 13.6 | 42.7 ± 14.6 | <0.001 |

| Education | 0.231 | ||

| No or primary school | 19 (32.8) | 180 (42.0) | |

| Junior to high school | 18 (31.0) | 131 (30.5) | |

| Diploma | 9 (15.5) | 34 (7.9) | |

| Bachelor or higher | 12 (20.7) | 84 (19.6) | |

| Marital status | 0.039 | ||

| Single | 32 (56.1) | 149 (34.9) | |

| Married | 17 (29.8) | 226 (52.9) | |

| Widowed/divorced/other | 8 (14.1) | 52 (12.2) | |

| Occupation | 0.502 | ||

| Officer | 13 (22.4) | 82 (19.3) | |

| Labor | 24 (41.4) | 169 (39.8) | |

| Housewife/student | 4 (6.9) | 121 (28.5) | |

| Unemployed | 17 (29.3) | 53 (12.4) | |

| Religion* | 0.236 | ||

| Buddhist | 56 (100.0) | 411 (96.5) | |

| Others | 0 (0) | 13 (3.5) | |

| Number of children | 0.023 | ||

| None | 19 (63.3) | 63 (35.2) | |

| 1–2 | 7 (23.3) | 83 (46.4) | |

| >2 | 4 (13.4) | 33 (18.4) | |

| Living status | 0.830 | ||

| Alone | 6 (11.3) | 17 (4.2) | |

| With family | 42 (79.2) | 386 (92.8) | |

| With others | 5 (9.5) | 13 (3.0) | |

| Social support | 0.001 | ||

| Good or excellent | 29 (56.9) | 304 (77.0) | |

| Moderate | 14 (27.4) | 69 (17.5) | |

| Very little or little | 8 (15.7) | 22 (5.5) | |

| Stressful life event(s) | 0.003 | ||

| None | 10 (17.2) | 165 (38.3) | |

| Yes | 48 (82.8) | 226 (61.7) | |

Notes: Numbers are n (%) or mean ± SD;

Fisher’s exact test.

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Clinical factors of patients with BD classified by suicide attempts

| Clinical factors | Suicide attempts | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 58) | No (n = 431) | ||

| Mania | 0.628 | ||

| No | 12 (32.4) | 157 (36.4) | |

| Yes | 25 (67.6) | 274 (63.6) | |

| Depression | <0.001 | ||

| No | 47 (81.0) | 414 (96.1) | |

| Yes | 11 (19.0) | 17 (3.9) | |

| Psychotic symptom(s) | 0.037 | ||

| No | 54 (93.1) | 351 (81.6) | |

| Yes | 4 (6.9) | 79 (18.4) | |

| Somatic illness | 0.376 | ||

| No | 42 (72.4) | 287 (66.6) | |

| Yes | 16 (27.6) | 144 (33.4) | |

| Psychotic comorbidity | 0.405 | ||

| No | 43 (82.7) | 378 (90.7) | |

| Alcohol/substance dependence | 8 (15.4) | 21 (5.0) | |

| Others | 1 (1.9) | 18 (4.3) | |

| Early age at onset (under 18) | 0.004 | ||

| No | 30 (54.6) | 99 (25.2) | |

| Yes | 25 (45.4) | 294 (74.8) | |

| Years of BD treatment | <0.001 | ||

| ≤5 | 48 (85.7) | 210 (52.8) | |

| >5 | 6 (10.7) | 98 (24.6) | |

| Median (min–max) | 1 (1–27) | 6 (1–40) | |

| Previous admission | 0.127 | ||

| No | 23 (40.4) | 220 (51.2) | |

| Yes | 34 (59.6) | 210 (48.8) | |

| Mental disorders in family | 0.143 | ||

| No | 37 (66.1) | 305 (77.0) | |

| Yes | 13 (23.2) | 70 (17.7) | |

| Suicide in family | 0.003 | ||

| No | 49 (92.4) | 405 (99.0) | |

| Yes | 4 (7.6) | 4 (1.0) | |

| Number of previous suicide attempts | <0.001 | ||

| None | 20 (34.5) | 348 (81.3) | |

| 1–2 times | 20 (34.5) | 71 (16.6) | |

| >2 times | 18 (31.0) | 9 (2.1) | |

| Previous suicidal ideation | <0.001 | ||

| No | 17 (29.3) | 315 (73.8) | |

| Yes | 41 (70.7) | 112 (26.2) | |

| Smoking | 0.112 | ||

| No | 39 (72.2) | 342 (81.4) | |

| Yes | 15 (27.8) | 78 (18.6) | |

| Alcohol drinking | 0.036 | ||

| No | 35 (64.8) | 327 (77.9) | |

| Yes | 19 (35.2) | 93 (22.1) | |

| Any substance abuse | 0.569 | ||

| No | 50 (92.6) | 396 (94.5) | |

| Yes | 4 (7.4) | 23 (5.5) | |

| Medication adherence | 0.001 | ||

| Good | 24 (47.1) | 288 (69.9) | |

| Intermittent or poor | 27 (52.9) | 124 (30.1) | |

| Antidepressant | <0.001 | ||

| No | 31 (53.4) | 332 (77.0) | |

| NE and/or SRI | 2 (3.5) | 24 (5.6) | |

| SSRI | 25 (43.1) | 75 (17.4) | |

| Antipsychotic | 0.001 | ||

| No | 8 (13.8) | 116 (26.9) | |

| Typical | 23 (39.6) | 171 (39.7) | |

| Atypical | 11 (19.0) | 108 (25.1) | |

| Both | 16 (27.6) | 36 (8.3) | |

| Anxiolytic | 0.041 | ||

| No | 18 (31.0) | 207 (48.0) | |

| Benzodiazepine | 33 (56.9) | 173 (40.1) | |

| Others | 4 (6.9) | 45 (10.4) | |

| Both | 3 (5.2) | 6 (1.4) | |

| Mood stabilizer | 0.008 | ||

| No | 5 (8.6) | 87 (20.2) | |

| Lithium | 25 (43.1) | 173 (40.1) | |

| Others | 16 (27.6) | 138 (32.0) | |

| Both | 12 (20.7) | 33 (7.7) | |

Note: Numbers are n (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; NE, norepinephrine; SRI, serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Using multivariate logistic regression, the six risk factors associated with suicide attempts were depression (adjusted OR = 3.88, 95% CI = 1.29–11.70), more than two previous suicide attempts (adjusted OR = 61.75, 95% CI = 17.34–219.88), stressful life event(s) (adjusted OR = 3.34, 95% CI = 1.18–9.48), intermittent or poor psychiatric medication adherence (adjusted OR = 3.78, 95% CI = 1.60–8.90), and duration of BD treatment (≤5 years) (adjusted OR = 4.73, 95% CI = 1.71–13.09). Psychotic symptom(s) decreased the odds of attempted suicide (adjusted OR = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.07 – 0.87) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression coefficient, adjusted OR and 95% CI of selected characteristics for suicide attempt in patients with BD

| Factors | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.88 (1.29–11.70) | 0.016 |

| Psychotic symptom(s) | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.24 (0.07–0.87) | 0.031 |

| Years of BD treatment | ||

| >5 | 1.00 | |

| ≤5 | 4.73 (1.71–13.09) | 0.003 |

| Number of previous suicide attempts | ||

| None | 1.00 | |

| 1–2 times | 2.34 (0.99–5.54) | 0.054 |

| >2 times | 61.75 (17.34–219.88) | <0.001 |

| Stressful life events | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.34 (1.18–9.48) | 0.024 |

| Medication adherence | ||

| Good | 1.00 | |

| Intermittent or poor | 3.78 (1.60–8.92) | 0.002 |

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

A risk score from each factor was derived from coefficients from the multivariate logistic regression model, and then transformed by dividing the smallest coefficient from the previous suicide attempt (0.85) to make it equal to 1. These scores were assigned to the final scores by rounding up (Table 4).

Table 4.

Item scores for characteristics related to suicide attempts derived from logistic regression coefficient

| Factors | Coefficient | Transformed score | Assigned score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||

| No | – | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 1.36 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Psychotic symptom(s) | |||

| No | – | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | −1.43 | −1.68 | −1.5 |

| BD treatment year(s) | |||

| >5 | – | 0 | 0 |

| ≤5 | 1.55 | 1.82 | 2.0 |

| No of previous suicide attempts | |||

| None | – | 0 | 0 |

| 1–2 times | 0.85 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| >2 times | 4.12 | 4.85 | 5.0 |

| Stressful life event(s) | |||

| No | – | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 1.20 | 1.42 | 1.5 |

| Medication adherence | |||

| Good | – | 0 | 0 |

| Intermittent or poor | 1.33 | 1.56 | 1.5 |

Abbreviation: BD, bipolar disorder.

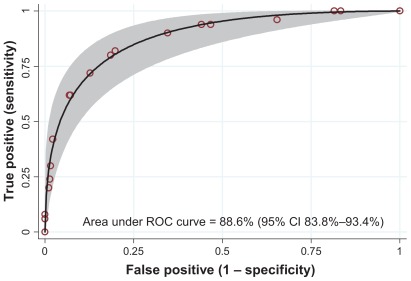

A total risk score, ranging from 0 to 10 in this dataset (out of a possible range of −1.5 to 11.5), explained an 88.6% probability of suicide attempts based on the ROC analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve and 95% CI band.

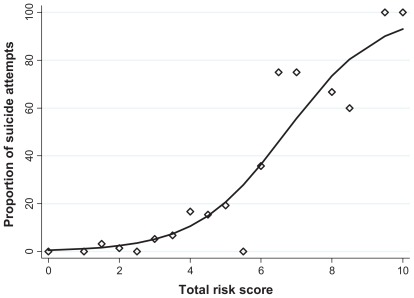

The proportion of suicide attempts estimated by risk from the logistic estimation was plotted against the actual risk of each total score. Estimated risk and actual risk corresponded well (P = 0.907; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Logistic estimated risk (solid line) against actual risk (dots) for suicide attempts by each total score.

A total risk score was then categorized into low risk (scores below 2.5), moderate (scores 2.5–8.5), and high risk (scores ≥9.0). The LHR+ for suicide attempts with low risk (scores <2.5), moderate risk (scores 2.5–8.0), and high risk (scores >8.0) were 0.11 (95% CI 0.04–0.32), 1.72 (95% CI 1.41–2.10), and 19.0 (95% CI 6.17–58.16), respectively. Individuals with an LHR+ in the low risk level were only 0.11 times more likely to attempt suicide, while those in the moderate and high-risk level were 1.72 and 19.0 times more likely to attempt suicide, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Risk levels categorized by suicide attempts among patients with BD, likelihood ratio of positive (LHR+) and 95% CI

| Risk level | Suicide attempts | LHR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 50) n (%) |

No (n = 379) n (%) |

|||

| Low (≤2.5) | 3 (1.4) | 212 (98.6) | 0.11 (0.04–0.32) | <0.001 |

| Moderate (2.5–8.0) | 37 (18.5) | 163 (81.5) | 1.72 (1.41–2.10) | <0.001 |

| High (>8.0) | 10 (28.6) | 4 (71.4) | 19.0 (6.17–58.16) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; CI, confidence interval; LHR+, likelihood ratio of positive.

Discussion

Indicators of suicide attempts

Depressive episodes, previous suicide attempt(s), stressful life event(s), intermittent or poor medication adherence, and shorter duration of BD treatment (<5 years) predicted suicide attempts. Psychotic symptom(s) provided an inverse association with suicide risk.

Previous suicide attempt(s) emerged as the most robust indicator of attempted suicide in this study, a factor which has also been observed elsewhere.9,12 Prior to the current suicide attempt, 65% of attempters had already attempted suicide, which is also comparable to previous research. Unlike previous studies, we classified a continuous number of previous suicide attempts into three groups (none, up to 2 times, and more than 2 times) for inclusion in our risk-scoring scheme. Increased odds ratios corresponded with an increased number of previous suicide attempt(s) (OR = 2.34 and 61.75 in the first and second groups, respectively). This likely reflects more severity, impulsiveness, and risks taken relative to the number(s) of past suicide attempts.

Signs and symptoms were also significant. Patients presenting with depression at the time of visit had almost four times the number of suicide attempts compared to those without depression. Likewise, more frequent suicide attempts during the depressed phase in BD patients have been reported previously.9–13 Conversely, psychotic symptoms negatively correlated with suicide attempts (OR = 0.24, risk score = −1.5 points) in our risk-scoring scheme. Patients with psychotic symptoms who were impaired in their ability to plan a suicide attempt might explain this result.

Stressful life event(s) was another preponderant factor predicting suicide attempts, and has played an important role in predicting suicide attempts among BD patients in many studies, particularly during depressive phases.9 This factor might trigger depression, then leading to a suicide attempt. In our study, all depressed patients (100%) had stressful life event(s) at the index date.

Noncompliance with treatment was another significant factor. Results showed an almost-fourfold increase in the number of suicide attempts among patients who admitted only sporadic or poor adherence to their psychiatric medications, compared to those who reported good adherence. The association of poor medication adherence (eg, long-term lithium treatment) with a higher risk of suicidal acts has been reported elsewhere.19 This is a potentially modifiable factor which can aid in decreasing suicide risk through a reduction of risk, severity of depression, or mixed state recurrences.

The greatest risk for suicide attempts (OR = 4.73) occurred among patients who had received less than 5 years of treatment, compared to those treated for more than 5 years. This finding replicates results from a similar study suggesting that the highest risk of suicide occurs in the first 5 years of treatment, and more particularly during the first year of illness.20,21 The time between BD onset to the time of diagnosis and the establishment of a sustained program of long-term, mood-stabilizing treatment can be as much as 5–10 years; this factor alone will almost certainly increase suicide risk.22

We were unable to demonstrate an association among several indicators suggested in previous studies. For example, associations with gender,9,10 early age at onset,9,10,12 family history of suicidal behaviors,11 multiple hospitalizations,9,23 and abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs were not observed.11 Inconsistencies might result from differences in our study population, methodology, measurement, and statistical analysis. In addition, some factors were found to be significant only in the univariate analysis. One reason for this could be the intercorrelation between one or more factors such as education and occupation, social support and living status, age, and substance abuse. Suicidal ideation, another predictive factor for suicide attempts in most studies, and history of suicide in the family, were removed when fitting the final model due to multicollinearity.

Strengths and limitations

The current study has several strengths. The gold standard for case assessment was the use of the number of suicide attempts to obtain an actual probability, rather than the use of a structured diagnostic interview such as the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), unlike other studies which obtained only a chance of suicide attempts through interviews.24 Moreover, specific risk factors were derived from BD populations; the developed scoring scheme should be more suitable for these vulnerable patients. Additionally, the use of factors that can be easily assessed on a routine basis indicates both its feasibility and value.

Some limitations should also be noted. Firstly, the study results may be limited to BD patients seeking treatment through a tertiary referral. Those referred to general hospitals or those who had not been referred to our setting might have different characteristics, such as the severity and lethality of the suicide method used. Secondly, retrospectively-collected data may be subject to incomplete or missing information. To ensure the validity of the current findings, we performed multiple imputation analysis and obtained the same final model from our original analysis with only slightly different odds ratios. Thirdly, the study design did not allow investigation of some indicators such as psychiatric disorder among family members, and so the impact of family history on risk of attempted suicide may be underestimated. Finally, despite using seven control subjects for each case, future research may benefit from a larger study population. Despite these limitations, this study provided a better understanding of the potential risk factors associated with suicide attempts among Thai patients with BD.

Application of a risk scoring scheme

To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a risk-scoring scheme for suicide attempts among patients with BD in Thailand. Unlike previous studies, we sought not only to determine risk indicators for suicide attempts in this particular population, but also further scored and developed a risk-scoring scheme by weighting each predictor with the probability of forecasting suicide attempts. This specific scheme for BD patients comprised elements of patient characteristics, signs and symptoms, and medical history that can be easily assessed on a routine basis. Our scoring scheme was able to reveal a high predictive probability, as demonstrated by an ROC curve of 88.6%.

According to the LHR+ among the three risk groups, this risk-scoring scheme can effectively identify patients with BD who are at risk for suicide attempts. High-risk patients should be considered for hospitalization or referred to a psychiatric hospital for further investigation and treatment. Although moderate LHR+ (1.72 times) was found in the moderate risk group, the ratio is statistically significant; risk scores higher than 1 reflect a noticeable risk for suicide attempts. Consequently, close monitoring by health care practitioners and family members, and more frequent treatment appointments, are required to ensure adequate treatment. Because suicide behaviors are persistent in patients with BD (although patients in the low risk group were very unlikely to attempt suicide), routine assessment for risk of attempted suicide is necessary.

The present risk-scoring scheme has applicable value in future research settings. It does require further validation before adoption in other settings, due to the variability of risk factors and their impact. We suggest applying the proposed risk-scoring scheme with a current suicide-screening tool, by asking patients for their current suicidal thoughts and previous suicide attempts to better enhance prediction of future suicide attempts.

Prospective external validation of this risk-scoring scheme should be carried out in future research. Predictive values of suicide attempts, added to a current suicide-screening tool, should be investigated further.

Conclusion

Our risk-scoring scheme, proposed specifically for use in patients with BD, comprises six key indicators that can be easily assessed on a routine basis to effectively identify patients at risk for attempted suicide. However, external validation of the scheme is required before adoption in other settings.

Acknowledgment

This study was in part financially supported by the Faculty of Medicine and the Graduate School, Chiang Mai University.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest in this research.

References

- 1.Baldessarini RJ, Pompili M, Tondo L. Suicide in bipolar disorder: Risks and management. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(6):465–471. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900014681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valtonen H, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppamaki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsa E-T. Suicidal ideation and attempts in bipolar I and II disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(11):1456–1462. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Mania-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–228. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isometsa ET, Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Lonngvist JK. Suicide in bipolar disorder in Finland. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):1020–1024. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai SY, Kuo CJ, Chen CC, Lee HC. Risk factors for completed suicide in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(6):469–476. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Mental Health Ministry of Public Health Thailand. Numbers and rates of psychiatric patients per 100,000 populations in 2008 – 2009. Bangkok, Thailand: 2010. [Accessed March 20, 2012]. Available from: http://www.dmh.go.th/report/report1.asp. Thai. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital. Suanprung psychiatric hospital report number of patients between 2007 to 2009. Chiang Mai, Thailand: 2010. [Accessed March 20, 2012]. Available from: http://www.suanprung.go.th/statt/index.html. Thai. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azorin JM, Kaladjian A, Adida M, et al. Risk factors associated with lifetime suicide attempts in bipolar I patients: findings from a French National Cohort. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(2):115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oquendo MA, Watemaux C, Brodsky B, et al. Suicidal behavior in bipolar mood disorder: clinical characterisics of attempters and nonattempters. J Affect Disord. 2000;59(2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harriss L. Suicide and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(6):693–704. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valtonen HM, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppamaki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsa ET. Prospective study of risk factors for attempted suicide among patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 Pt 2):576–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryu V, Jon DI, Cho HS, et al. Initial depressive episodes affect the risk of suicide attempts in Korean patients with bipolar disorder. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(5):641–647. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.5.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ. Long-term lithium treatment in the prevention of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patients. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(3):179–183. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00000439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pompili M, Innamorati M, Raja M, et al. Suicide risk in depression and bipolar disorder: Do impulsiveness-aggressiveness and pharmacotherapy predict suicidal intent? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(1):247–255. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital. Suanprung’s outpatient and inpatient services treat most psychiatric illnesses. Chiang Mai, Thailand: 2010. [Accessed March 17, 2012]. Available from: http://www.suanprung.go.th/eng/top_five.php. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Accessed April 2, 2012]. [cited 2011 August 19]: Available from: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en#/F30-F39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akobeng AK. Understanding diagnostic tests 2: likelihood ratios, pre-and post-test probabilities and their use in clinical practice. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(4):487–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Pinto A, Mosquera F, Alonso M, et al. Suicidal risk in bipolar I disorder patients and adherence to long-term lithium treatment. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 Pt 2):618–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldessarini RJ, Pompili MP, Tondo L. Bipolar disorder. In: Simon GE, Hales RE, editors. Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 1st ed. Arlington, VA: The American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006. pp. 277–299. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dilsaver SC, Chen YW, Swann AC, Shoaib AM, Tsai-Dilsaver Y, Krajewski KJ. Suicidality, panic disorder and psychosis in bipolar depression, depressive-mania and pure-mania. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73(1–2):47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Suppes T, Tondo L, Becker I, Lipschitz DS. Pediatric-onset bipolar disorder: a neglected clinical and public health problem. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1995;3(4):171–195. doi: 10.3109/10673229509017185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oquendo MA, Currier D, Mann JJ. Prospective studies of suicidal behavior in major depressive and bipolar disorders: what is the evidence for predictive risk factors? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(3):151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tangseree T, Aroonpongpaisal S, Chiravatkul A, et al. Development for depression and suicidal risk screening test (version 2009) J Psychiatr Assoc Thailand. 2009;54:287–297. [Google Scholar]