Abstract

When investigating fractal phenomena, the following questions are fundamental for the applied researcher: (1) What are essential statistical properties of 1/f noise? (2) Which estimators are available for measuring fractality? (3) Which measurement instruments are appropriate and how are they applied? The purpose of this article is to give clear and comprehensible answers to these questions. First, theoretical characteristics of a fractal pattern (self-similarity, long memory, power law) and the related fractal parameters (the Hurst coefficient, the scaling exponent α, the fractional differencing parameter d of the autoregressive fractionally integrated moving average methodology, the power exponent β of the spectral analysis) are discussed. Then, estimators of fractal parameters from different software packages commonly used by applied researchers (R, SAS, SPSS) are introduced and evaluated. Advantages, disadvantages, and constrains of the popular estimators ( power spectral density, detrended fluctuation analysis, signal summation conversion) are illustrated by elaborate examples. Finally, crucial steps of fractal analysis (plotting time series data, autocorrelation, and spectral functions; performing stationarity tests; choosing an adequate estimator; estimating fractal parameters; distinguishing fractal processes from short-memory patterns) are demonstrated with empirical time series.

Keywords: fractal, 1/f noise, ARFIMA, long memory

Measuring Fractality

Fractal patterns have been observed in numerous scientific areas including biology, physiology, and psychology. A specific structure known as pink or 1/f noise represents the most prominent fractal phenomenon. Because it is intermediate between white noise and red or Brown noise, it exhibits both stability and adaptability, thus properties typical for healthy complex systems (Bak et al., 1987). Consequently, pink noise serves as an adequate model for many biological systems and psychological states. For instance, pink noise was found in human gait (Hausdorf et al., 1999), rhythmic movements like tapping (Chen et al., 1997, 2001; Ding et al., 2002; Delignières et al., 2004; Torre and Wagenmakers, 2009), visual perception (Aks and Sprott, 2003), brain activity (Linkenkaer-Hansen, 2002), heart rate fluctuations, and DNA sequences (Hausdorf and Peng, 1996; Eke et al., 2002; Norris et al., 2006). Hence, one of the main objectives for measuring fractality is to distinguish reliably between fractal (healthy) and non-fractal (unhealthy) patterns for diagnostic purposes. For instance, many diseases result from dysfunctional connections between organs, which can be viewed as loss of adaptive behavior of the body as a complex system. Therefore, deviations from the 1/f structure can serve as indicators for disease severity.

Additionally, Gilden et al. (1995), Van Orden et al. (2003, 2005) discovered fractality in controlled cognitive performances and other mental activities. The most striking feature of the observed patterns was their long memory. Serial correlations were not necessarily large in absolute magnitude but very persistent, which is typical for 1/f noise. Since memory characteristics are decisive for the development of a process, an accurate measurement of fractality is indispensible for correct statistical inference concerning the properties of empirical data and precise forecasting. Therefore, further important goals of fractal analyses are to test for the effective presence of genuine long-range correlations and provide an accurate estimation of their strength.

There are different methodological approaches, and their respective statistical parameters, to capture fractality. For each parameter, numerous estimators have been developed, but there is no clear winner among them (Stroe-Kunold et al., 2009; Stadnytska et al., 2010; Stadnitski, 2012). Furthermore, statistical characteristics of some non-fractal empirical structures can resemble those of 1/f noise, which may cause erroneous classifications (Wagenmakers et al., 2004; Thornton and Gilden, 2005). Therefore, proper measurement of fractality and reliable discrimination of pink noise from other fractal or non-fractal patterns represent crucial challenges for applied researchers. The main purposes of this paper are to introduce appropriate measurement strategies to practitioners and to show how to use them in applied settings. The article intends to outline the basics of fractal analysis by providing insight into its concepts and algorithms. Detailed descriptions of the methods are beyond the scope of this paper and can be found in Beran (1994), Brockwell and Davis (2002), Delignières et al. (2006), Eke et al. (2002), Jensen (1998), and Warner (1998).

Theoretical Characteristics of Fractal Patterns

What are essential attributes of 1/f noise? The answer is long memory and self-similarity. Fractals are self-similar structures where the whole has the same shape as its parts (e.g., broccoli or the Koch snowflake). Hence, characteristics of a 1/f noise process remain similar when viewed at different scales of time or space. This implies the following statistical properties: (1) a hyperbolically (i.e., very slow) decaying autocorrelation function (ACF) and (2) a specific relation between frequency (f) and size of process variation (S): S(f)∝ 1/f. This so-called power low means that the power (variance or amplitude) of the 1/f noise process is inversely proportional to the frequency.

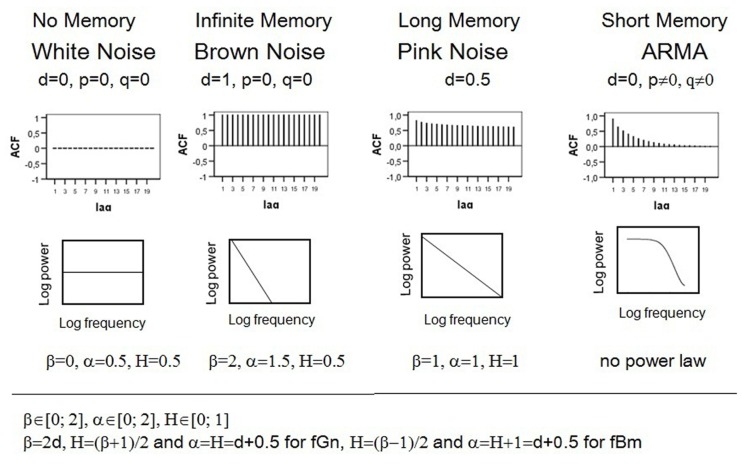

The ACF describes the correlation of a signal with itself at different lags. In other words, it reflects the similarity between observations in reference to the amount of time between them. Hyperbolically decaying autocorrelations imply statistical dependence between observations separated by a large number of time units or a long memory of the process. In contrast, if a process has a short-memory and can be predicted by its immediate past, the autocorrelations decay quickly (e.g., exponentially) as the number of intervening observations increases. White noise is a sequence of time-ordered uncorrelated random variables, sometimes called random shocks or innovations, and therefore has no memory. Brown noise or a random walk evolves from integrating white noise, and thus can also be represented as the sum of random shocks. As a result, the impact of a particular innovation does not dissipate and a random walk remembers the shock forever, which implies an infinite memory and no decay in ACF. The upper section of Figure 1 compares the ACF of processes with different memory characteristics.

Figure 1.

Autocorrelation functions, logarithmic power spectra and parameter values of different fractal and non-fractal patterns.

Granger and Joyeux (1980) and Hosking (1981, 1984) demonstrated that hyperbolically decaying autocorrelations of pink noise can be parsimoniously modeled by means of the differencing parameter d of the Box–Jenkins autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) methodology, allowing it to take on continuous values (Box and Jenkins, 1970). The ARIMA method describes processes through the three parameters p, d, and q. For example, the following process

is called ARMA (1, 1) because it contains one autoregressive (Yt − 1) and one moving average term (ut − 1). Therefore, the value of the autoregressive parameter p reflects how many preceding observations influence the current observation. The value of the moving average term q describes how many previous random shocks must be taken into account when describing the dependency present in the time series. φ is the autoregressive prediction weight and θ is the proportion of the previous random component that still affects the observation at a time T. Within the Box–Jenkins ARIMA framework, d is whole number and refers to the order of differencing that is necessary to make a process stationary (d = 0). Statistical characteristics of a stationary process do not change over time or position, i.e., mean, variance, and autocorrelation remain stable. Thus the ARMA (1, 1) process can also be written as ARIMA (1, 0, 1). White noise is ARIMA (0, 0, 0). Models with d = 1 correspond to a process with an infinite persistence of random shocks and are called integrated of order 1. Brown noise is ARIMA (0, 1, 0). Autoregressive fractionally integrated moving average (ARFIMA) modeling extends the traditional Box–Jenkins approach by allowing the differencing parameter d to take on non-integer values. This enables ARFIMA-models to give parsimonious descriptions of any long-range dependencies in time series. Pink noise has d of 0.5. Stationary fractal processes with finite long memory can be modeled with 0 < d < 0.5. For 0.5 ≤ d ≤ 1, the process is non-stationary. Consult Beran (1994) and Brockwell and Davis (2002) for more background on long memory and ARFIMA modeling.

The so-called power spectrum determines how much power (i.e., variance or amplitude) is accounted for by each frequency in the series. The term frequency describes how rapidly things repeat themselves. Thus, there exist fast and slow frequencies. For instance, a time series with T = 100 observations can be reconstructed in 50 periodic or cyclic components (T/1, T/2, T/3,…, 2). The frequency is the reciprocal of the period and can be expressed in terms of number of cycles per observation. Therefore, f = 0 implies no repetition, f = 1/T the slowest, and f = 0.5 the fastest frequency. Spectral density function gives the amount of variance accounted for by each frequency we can measure. The analysis of power distribution can be seen as a type of ANOVA where the overall process variance is divided into variance components due to independent cycles of different length. If the data are cyclic, there are a few so-called major frequencies that explain a great amount of the series’ variance (i.e., all of the series’ power is concentrated at one or a few frequencies). For non-periodic processes like white noise, the variance is equally distributed across all possible frequencies. For pink noise, there is a special kind of relationship between frequency and variance, which is expressed by the following power low: S(f)∝ 1/f. Self-similarity of this process implies that its variance is inversely proportional to its frequency. This property becomes more vivid if the power spectrum is plotted on a log–log scale, showing that the logarithmic power function of 1/f noise follows a straight line with slope –1. In contrast, the power of Brown noise falls off rapidly with increasing frequency, which means that low frequency components predominate. As a result, the log–log power function of Brown noise is a line with a slope of −2. The logarithmic power spectrum of white noise has a slope of 0. Denoting the power spectrum function 1/f β, where β is called the power exponent, we obtain β = 0 for white noise, β = 2 for Brown noise, and β = 1 for pink noise. For short-memory (e.g., autoregressive) processes, the log–log power spectrum in not a straight line because the linear relation between the power and the frequency breaks down at the low frequencies where random variation appears. As a result, a flat plateau (the zero slope of white noise) dominates low frequencies in spectral plots. The bottom section of Figure 1 shows the power spectra of the discussed processes. For more details on spectral analyses, consult Warner (1998).

Self-similarity of pink noise can also be expressed by the following power low: F(n) ∝ n α with α = 1. Dividing a process in intervals of equal length n allows viewing it on different scales. Fluctuations (F) of pink noise are proportional to n, i.e., they increase with growing interval length. The scaling exponent α of Brown noise is 1.5; white noise has α of 0.5.

The so-called Hurst phenomenon represents a further manifestation of self-similarity (Hurst, 1965). It expresses the probability that an event in a process is followed by a similar event. This probability, expressed as the Hurst coefficient (H), is 0.5 for both white and Brown noises, which is not surprising because white noise is a sequence of independent innovations and Brown noise consists of uncorrelated increments. The Hurst coefficient of self-similar processes deviates from 0.5. For pink noise, H = 1. In general, we distinguish two different classes of fractal signals: fractional Brownian motions (fBm) and fractional Gaussian noises (fGn; Mandelbrot and van Ness, 1968; Mandelbrot and Wallis, 1969). Gaussian noises are stationary processes with constant mean and variance, whereas Brownian motions are non-stationary with stationary increments. Differencing Brownian motion creates Gaussian noise and summing Gaussian noise produces Brownian motion. The related processes are characterized by the same Hurst coefficient.

To summarize, long memory and self-similarity are specific characteristics of 1/f noise. These properties become manifest in the hyperbolically decaying ACF and power lows. The differencing statistic d, the power exponent β, the scaling exponent α, and the Hurst coefficient H are parameters that reflect fractality. The expected theoretical parameter values of the pink noise are d = 0.5, β = 1, α = 1, H = 1. Figure 1 outlines relations between parameters and contrasts the autocorrelation and spectral density functions of 1/f noise with those of other processes.

To understand subsequent explanations, it is important to conceive the difference between the following concepts: parameter, estimator, and estimate. A parameter is a quantity that defines a particular system, e.g., the mean μ of the normal distribution. H, β, α, and d are fractal parameters that express exactly the same statistical characteristics. The formulas presented in Figure 1 allow for unequivocal transformations from one quantity into the other. For instance, a stationary process with the scaling exponent α = 0.8 can be alternatively specified by H = 0.8, d = α − 0.5 = 0.3, or β = 2, d = 0.6. An estimator is a rule or formula that is used to infer the value of an unknown parameter from the sample information. For each parameter, there are usually different estimators with diverse statistical properties. In contrast to parameters, estimators are not numbers but functions characterized by their distributions, expectancy values, and variances. For example, μ can be estimated using the arithmetic mean or the median Both methods are unbiased, which implies that their expected values match However, is the better estimator of μ because of its smaller variance ensuring narrower confidence intervals and thus more precise inference. The superiority of is determined mathematically. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to find out the best estimator this way. In such cases, Monte Carlo simulations represent adequate tools to determine the best method to use under the given circumstances. For instance, computational algorithms can generate a population with a known parameter value, e.g., a process with α = 1. Repeated samples of the same size can be drawn from this population, e.g., 1000 time series with T = 500, and different estimators can be applied to the series. As a result one gets 1000 estimates of the parameter per method. Estimate is a particular numerical value obtained by the estimator in an application. Good estimators are unbiased, i.e., their means equal the true parameter value, and have small variability, i.e., their estimates do not differ strongly. Considering that just one estimate per method is available in a typical research situation, an estimator with the narrow range, e.g., for α = 1, is obviously better that the one with the broad range, e.g.,

Estimators of Fractal Parameters

Numerous procedures for measuring the fractal parameters β, α, H, and d have been developed in recent years. Table 1 includes estimators that are available in software packages traditionally used by psychologists (R, SPSS, and SAS). The methods can be assigned to three categories: (1) exact or approximate maximum likelihood (EML or AML) ARFIMA estimation of d with the corresponding conditional sum of squares (CSS) algorithm; (2) detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) and signal summation conversion (SSC), fractal methods predicated on the relationship F(n) ∝ n α; (3) periodogram based procedures like power spectral density (PSD), Whittle (FDWhittle), Sperio (fdSperio), and Geweke–Porter-Hudak (fdGPH). The periodogram is an estimate of the spectral density function.

Table 1.

Estimators of fractal parameters from statistical packages R, SAS, and SPSS.

| Method | Outputs | Available | Command |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARFIMA | |||

| EML | SAS: IML subroutine FARMAFIT | Fitting ARFIMA (1, d, 1): call farmafit(d, ar, ma, sigma, x, opt=1) p=1 q=1; print d ar ma sigma; | |

| CSS | SAS: IML subroutine FARMAFIT | call farmafit(d, ar, ma, sigma, x, opt=0) p=1 q=1; print d ar ma sigma; | |

| AML | R: library fracdiff | summary(fracdiff(x, nar=1, nma=1)) | |

| FRACTAL | |||

| DFA | R: library fractal | DFA(x, detrend="bridge", sum.order=1) | |

| SSC | R-Code SSC.R | Download the file SSC.R from http://www.psychologie.uni-heidelberg.de/projekte/zeitreihen/R_Code_Data_Files.html then click “read R-code” from the data menu and start the test via command SSC(x) | |

| PERIODOGRAM | |||

| lowPSD | SPSS, SAS, R | SPSS-, SAS-, and R-Codes in Appendix | |

| lowPSDwe | R-Code lowPSDwe.R | Download the file lowPSDwe.R from http://www.psychologie.uni-heidelberg.de/projekte/zeitreihen/R_Code_Data_Files.html then click “read R-code” from the data menu and start the test via command PSD(x) | |

| hurstSpec | R: library fractal | hurstSpec(x) | |

| fdGPH | R: library fracdiff | fdGPH(x) | |

| fdSperio | R: library fracdiff | fdSperio(x) | |

| FDWhittle | R: library fractal | FDWhittle(x) | |

Autoregressive fractionally integrated moving average algorithms were described and evaluated by Stadnytska and Werner (2006) and Torre et al. (2007). Eke et al. (2000), Delignières et al. (2006), Stroe-Kunold et al. (2009), Stadnytska et al. (2010), Stadnitski (2012) systematically analyzed different fractal and periodogram based methods. What are the key findings of these studies? First, all estimators require at least 500 observations for acceptable measurement accuracy. Further, for researchers studying fractality, it is essential to know that there exist different procedures with diverging characteristics. Unfortunately for the researcher, none of the procedures is superior to the other. The central difficulty is that there is no clear winner among them. Simulation studies on this topic demonstrated that the performance of the methods strongly depends on aspects like the complexity of the underlying process or parameterizations. As a result, elaborated strategies to estimate the fractality parameters are necessary. Thornton and Gilden (2005) developed a spectral classifier procedure that estimates the likelihood of a time series by comparing its power spectrum with spectra of the competing memory models. Stadnytska et al. (2010) proposed a method to estimate the long memory parameter d that combines different techniques and incorporates ARFIMA approaches from Wagenmakers et al. (2004). The application of this strategy to an empirical time series will be presented later. A brief overview of procedures summarized in Table 1 precedes the empirical demonstration.

ARFIMA methods

The most popular estimators of the fractional differencing parameter d are the EML method proposed by Sowell (1992a), the CSS approach introduced by Chung (1996) and the approximate method (AML) of Haslett and Raftery (1989). The main advantage of the ARFIMA methods is the possibility of the joint estimation of the short-memory and long memory parameters. This solves a potential finite-sample problem of biased overestimation of fractality in time series which contain both long-range and short-range components (see Sowell, 1992b, for details). Moreover, goodness of fit statistics based on the likelihood function, like the Akaike information criterion (AIC) or the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), allow to determine the amount of “short-term contamination” and enable a reliable discrimination between short- and long memory processes.

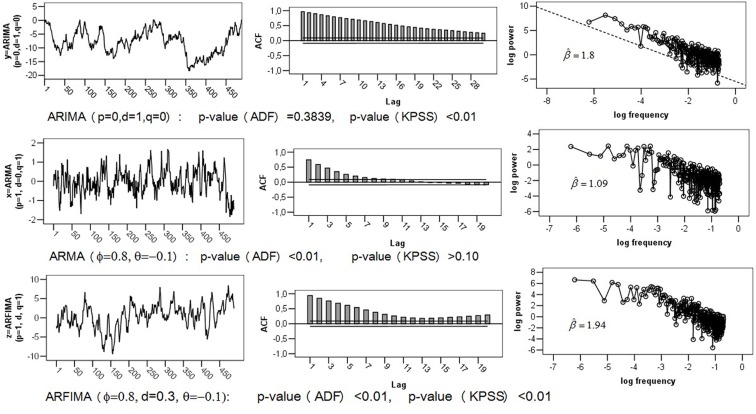

The greatest problem with ARFIMA estimators is that they work only for stationary series, because their range is confined to (0; 0.5). This entails erroneous classifications of non-stationary processes with d > 0.5 as 1/f noise. Recall that the theoretical parameter values of pink noise are d = 0.5, β = 1, α = 1, H = 1. To illustrate this problem, a Brown noise series [ARIMA (0, 1, 0) with d = 1, β = 2, α = 1.5, H = 0.5] of length T = 500 was simulated. The upper section of Figure 2 shows the series with its ACF and logarithmic power spectrum. Applying ARFIMA methods to this data provided estimates of d close to Hence, checking for stationarity is a necessary precondition for ARFIMA estimation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of ACF and power spectra of empirical Series: (1) Brown Noise or ARIMA (0, 1, 0); Short-Memory Series ARIMA (1, 0, 1); (3) Fractal Series ARFIMA (1, d, 1) with d = 0.3.

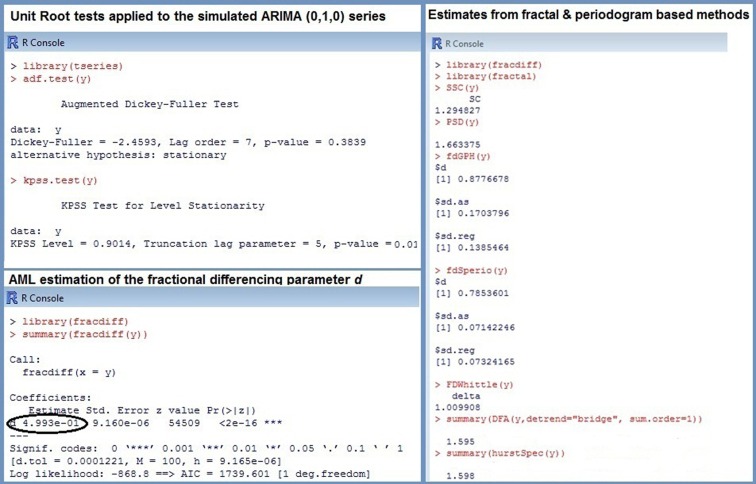

Special procedures called unit root tests were developed to prove stationarity (see Stadnytska, 2010, for a comprehensive overview). The augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test, the most popular method available in statistical packages R or SAS, checks the null hypothesis d = 1 against d = 0. Hence, an empirical series with d close to 0.5 will probably be misclassified as non-stationary. In contrast, the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test acts on the assumption that process is stationary (H0: d = 0). Therefore the combination of both procedures allows to determine the properties of the series under study: (1) if the ADF is significant and the KPSS is not, then the data are probably stationary with d ∈ (0; 0.5); (2) in the Brown noise case, an insignificant ADF and a significant KPSS results are expected; (3) d ∈ (0; 1), if both tests are significant. Applying the unit root tests to the simulated Brown noise series showed the following p-values: pADF = 0.3839 and pKPSS < 0.01 (see Figure 3). According to this outcome, the series is probably non-stationary, and estimating fractal parameters with the ARFIMA methods is inappropriate.

Figure 3.

R commands and results for the simulated Brown noise ARIMA (0, 1, 0) series.

Fractal and periodogram based methods

In contrast to ARFIMA procedures, methods like PSD (Eke et al., 2002), DFA (Peng et al., 1993), or SSC (Eke et al., 2000) can be applied directly to different classes of time series. Consequently, they represent adequate tools for distinguishing fGn and fBm signals. For the simulated Brown noise series the following results were obtained: (see Figure 3). All estimates were converted to using the formulas in Figure 1 to make the comparison more convenient. For instance, DFA outputs (see Table 1; Figure 3), thus The estimate of β presented in Figure 3 is hence Recall that the true d-value of Brown noise is 1, therefore, compared to the ARFIMA algorithms, the most estimates reflect the parameter rather accurate.

However, due to considerably larger biases and more pronounced SEs, the precision of fractal and periodogram based methods is distinctly inferior to that of the ARFIMA approaches. Moreover, algorithms like PSD, DFA, or SSC use different data transformations like detrending or filtering. As a result, the performance of estimators strongly depends on the manipulations employed. For instance, numerous modifications have been suggested to improve the PSD estimation. The method designated as lowPSDwe consists of the following operations: (1) subtracting the mean of the series from each value, (2) applying a parabolic window to the data (w), (3) performing a bridge detrending (e), (4) estimating β excluding 7/8 of high-frequency power estimates (low). The estimator lowPSD is constructed without transformations 2 and 3. Simulation studies demonstrated that lowPSD were more accurate for fGn noises whereas lowPSDwe were accurate for fBm signals (Delignières et al., 2006; Stadnitski, 2012).

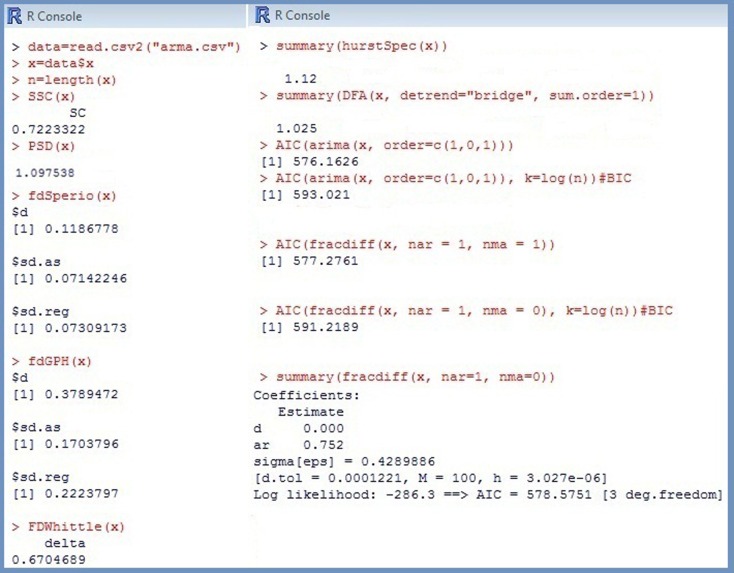

The greatest disadvantage of fractal and periodogram based methods is their poor performance for complex processes that combine long- and short-term components. Stadnitski (2012) demonstrated that FDWhittle, the best procedure for pure noises, showed the worst accuracy in complex cases. To illustrate this problem, the following two series with T = 500 observations were simulated: a short-memory ARIMA (1, 0, 1) model with d = 0, φ = 0.8, and þeta = − 0.1; a long memory ARFIMA (1, d, 1) model with d = 0.3, φ = 0.8, and þeta = −0.1 (see Figure 2). Recall that within the scope of the ARFIMA methodology the short-memory components of a time series can be captured through the autoregressive terms weighted with φ and the moving average terms weighted with θ. The following estimates were obtained for the short-memory series with the true d-value of (see Figure 4). Hence, most estimators erroneously indicate a 1/f pattern for this non-fractal series. For the long memory series with the true d-value of 0.3, we obtained Except for fdGPH and fdSperio, we observed here a pronounced positive bias. As a result, this stationary fGn series could be misclassified as a non-stationary fBm signal.

Figure 4.

R output for the simulated short-memory ARIMA (1, 0, 1) series.

The following example demonstrates the advantages of ARFIMA methodology for complex cases. Since not every data generating process can adequately be represented by a simple (0, d, 0)-structure, information Criteria AIC and BIC of different ARFIMA-models were compared first. Recall that the smallest AIC or BIC indicate the best model. The results summarized in Table 2 clearly favored the (1, d, 1)-pattern for the simulated long memory ARFIMA (1, d, 1) with d = 0.3, φ = 0.8, and þeta = − 0.1. The AML estimates for this structure were The point estimate of d is comparable to those of fdGPH and fdSperio, but AML has a distinctly smaller SE (SEAML = 0.007 vs. SEfdGPH = 0.17, SEfdSperio = 0.07) assuring smaller confidence intervals, i.e., a more precise measurement. For the short-memory series with d = 0, φ = 0.8, and þeta = −0.1, there were two plausible models: (1, 0, 1) according to the AIC and (1, d, 0) according to the BIC. Fitting the (1, d, 0) model to the data provided (see Figure 4). Therefore, in both cases the series was correctly identified as non-fractal short-memory structure.

Table 2.

Values of the information criteria AIC and BIC for the simulated short-memory ARMA and long memory ARFIMA series in dependence of the fitted model.

| Fitted model | ARMA (φ = 0.8, d = 0. þeta = − 0.1) |

ARFIMA (φ = 0.8, d = 0.3, φ = − 0.1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | BIC | AIC | BIC | |

| (2, 0, 2) | 579.9649 | 605.2525 | 1439.242 | 1464.530 |

| (2, 0, 1) | 578.1632 | 599.2363 | 1439.540 | 1460.613 |

| (1, 0, 2) | 578.1626 | 599.2356 | 1438.977 | 1460.050 |

| (2, 0, 0) | 576.2489 | 593.1073 | 1439.350 | 1456.209 |

| (0, 0, 2) | 576.2489 | 678.1116 | 1763.675 | 1780.533 |

| (1, 0, 1) | 576.1626 | 593.0210 | 1439.625 | 1456.483 |

| (1, 0, 0) | 577.5258 | 590.1697 | 1489.436 | 1502.080 |

| (0, 0, 1) | 738.9594 | 751.6032 | 2059.512 | 2072.156 |

| (0, 0, 0) | 984.6744 | 993.0052 | 2573.536 | 2581.965 |

| (2, d, 2) | 580.3508 | 605.6384 | 1440.078 | 1465.366 |

| (2, d, 1) | 578.3731 | 599.4461 | 1438.590 | 1459.663 |

| (1, d, 2) | 578.3752 | 599.4482 | 1438.261 | 1459.334 |

| (2, d, 0) | 576.5114 | 593.3699 | 1437.906 | 1454.764 |

| (0, d, 2) | 588.8440 | 605.7024 | 1465.847 | 1482.706 |

| (1, d, 1) | 577.2761 | 594.1346 | 1436.262 | 1453.121 |

| (1, d, 0) | 578.5751 | 591.2189 | 1447.913 | 1460.557 |

| (0, d, 1) | 592.3358 | 604.9797 | 1526.298 | 1538.942 |

| (0, d, 0) | 612.2110 | 620.5418 | 1761.094 | 1769.523 |

Bold are estimates from the models with the smallest Akaike information criterion (AIC) or Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

Fractal Analysis with Empirical Data

As demonstrated previously, strategic approach is necessary for a proper measurement of fractal parameters. In the following we show how to apply the estimation methodology proposed by Stadnytska et al. (2010) to empirical data by employing the R software.

R can be downloaded free of charge from http://www.r-project.org/. To perform fractal analyses, we need three packages (fracdiff, fractal, tseries) that do not come with the standard installation. Click install packages under the packages menu, select these packages and confirm with ok. Now the packages will be available for use in the future. Since every command of R is a function that is stored in one of the packages (libraries), you have to load the libraries fracdiff, fractal, tseries each R session before performing fractal analyses. To do so, click load packages under the packages menu then choose the package and confirm with ok.

R is able to read data in many different formats. An easy way to get an excel file into R is to save it in the csv format, and read it using the command like

data=read.csv2 (“C:/ /data.csv”)

Now data is a data frame with named columns ready for analysis. If data contains three variables x, y, and z, you can analyze them with the commands like

mean(data$x) summary(data$y) cor(data$x,data$z)

You can easily rename variables using the following command x=data$x.

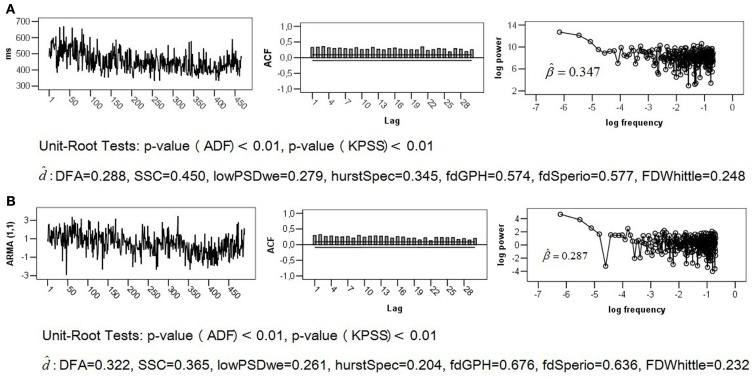

The empirical series of length T = 512 that is analyzed below was generated in the context of a reaction time task experiment described by Stadnitski (2012). Response time between stimulus presentation and reaction served as dependent measurement (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

ADF and log–log plot of (A) empirical series obtained from temporal estimation task; (B) simulated ARIMA (1, 0, 1) series with φ = 0.99, and þeta = −0.92.

The first step of the analysis is to plot a series and examine its ACF and logarithmic power spectrum. Recall that for 1/f noise we expect a slower hyperbolic decaying autocorrelations and a straight line with a slope of −1 in the log plot. If the autocorrelations decline quickly or exponentially, the series is definitely non-fractal.

plot(x, ty=``l``) acf(x) PSD-Code of R (see Appendix)

Satisfactory stability in level and variability of the series as well as a slow decay of its ACF, depicted in Figure 5A, signalized a finite long memory typical for fractal noises. The negative slope is, however, distinctly smaller than 1. It is important to know that the original PSD procedure is not always the best method. Simulation studies demonstrated that excluding the high-frequency spectral estimates from fitting for the spectral slope may improve estimation (Taqqu and Teverovsky, 1997; Eke et al., 2000). Applying the lowPSD method (see Appendix) provided Thus, the logarithmic power spectrum of the series seems to be compatible with the pink noise pattern. The problem is that the log–log power spectrum of short-memory ARMA (p, q) processes can resemble the spectrum of 1/f noise (see, for example, the log plot of the ARMA (1,1) structure in Figure 2).

Unit root tests may help to find out more about the statistical properties of the series.

adf.test(x) kpss.test(x)

The following p-values were observed for the analyzed series: pADF < 0.01 and pKPSS < 0.01. According to these results, the data under study is probably not Brown noise but it can be both fGn and fBm. Thus, ARFIMA as well as fractal and periodogram based method are appropriate here (see commands in Table 1). To make the comparison of results more convenient, the fractal, and periodogram based estimators were converted to and presented in Figure 5A. The estimates ranged from 0.248 to 0.577 indicating a fractal pattern. We know, however, that these methods overestimate fractality in time series that contain both long-range and short-range components. Since the obtained values were all smaller than 0.6, the ARFIMA analysis appeared appropriate.

The preceding analyses do not allow rejecting the hypothesis of non-fractality of the analyzed series. Therefore AIC and BIC of different short- and long memory models were compared. The following commands compute AIC of the (1, d, 1) and (1, 0, 1) models:

AIC(fracdiff(x, nar = 1, nma = 1)) AIC(arima(x, order=c(1,0,1)))

To obtain BIC instead of AIC, use

AIC(fracdiff(x, nar = 1, nma = 1), k=log(n)) AIC(arima(x, order=c(1,0,1)), k=log(n)),

n is the number of observations (see Figure 4).

The results summarized in Table 3 indicated either the long memory model (1, d, 2; the smallest AIC) or the short-memory model (1, 0, 1; the smallest BIC). Fitting the (1, d, 2) pattern to the data with the command “summary(fracdiff(x, nar=1, nma=2)),” provided the d estimate very close to Therefore, the series is probably not generated from the 1/f noise process.

Table 3.

Values of the information criteria AIC and BIC for the empirical time series.

| Model ARMA | AIC | BIC | Model ARFIMA | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0, 0, 0) | 5308.030 | 5316.506 | (0, d, 0) | 5181.524 | 5190.001 |

| (1, 0, 0) | 5256.566 | 5269.281 | (1, d, 0) | 5170.354 | 5183.069 |

| (0, 0, 1) | 5274.145 | 5286.860 | (0, d, 1) | 5163.365 | 5176.080 |

| (1, 0, 1) | 5158.735 | 5175.688 | (1, d, 1) | 5161.513 | 5178.466 |

| (2, 0, 1) | 5160.726 | 5181.917 | (2, d, 1) | 5156.040 | 5177.208 |

| (1, 0, 2) | 5160.729 | 5181.920 | (1, d, 2) | 5156.016 | 5177.232 |

| (2, 0, 0) | 5226.219 | 5243.172 | (2, d, 0) | 5165.411 | 5182.365 |

| (0, 0, 2) | 5256.336 | 5273.29 | (0, d, 2) | 5162.237 | 5179.190 |

| (2, 0, 2) | 5162.699 | 5188.129 | (2, d, 2) | 5158.016 | 5183.446 |

Bold are estimates from the models with the smallest AIC or BIC.

Fitting the (1, 0, 1) model to the data using “arima(x, order=c(1,0,1)),” resulted in and To demonstrate that short-memory series with such parameter values can mimic the statistical properties of the pink noise, we simulated the ARIMA (1, 0, 1) models of length T = 512 with the true values d = 0, φ = 0.99, and þeta = − 0.92. Figure 5B shows that its ACF, log plot, and estimates obtained from fractal and periodogram based methods are very similar to those of the analyzed empirical series. For explanations of this phenomenon, consult Thornton and Gilden (2005), Wagenmakers et al. (2004), and Stadnitski (2012). Detailed descriptions of R analyses are presented in Appendix.

Concluding Remarks

Self-similarity and long memory are essential characteristics of a fractal pattern. Slow hyperbolically decaying autocorrelations and power lows reflect these properties, which can be expressed with the correspondent parameters d, β, α, and H. The fractal parameters express exactly the same statistical characteristics, thus each quantity can be converted to the other. The expected theoretical values of pink noise are d = 0.5, β = 1, α = 1, H = 1. There are two major types of estimators for these parameters: ARFIMA algorithms and procedures searching for power laws. The former are very accurate methods capable of measuring both long- and short-term dependencies, but they can handle only stationary processes. The latter are adequate procedures for stationary and non-stationary data, their precision, however, is distinctly inferior to that of the ARFIMA methods. Moreover, they tend to overrate fractal parameters in series containing short-memory components. The greatest problem is that no estimator is superior for a majority of theoretical series. Moreover, in a typical research situation it is usually unclear what kind of process generated empirical data. Consequently, the estimation of fractality requires elaborate strategies. The spectral classifier procedure by Thornton and Gilden (2005) and the ARFIMA estimation proposed by Stadnytska et al. (2010) are examples of such strategic approaches. Furthermore, depending of the hypotheses of the research, diverse key objectives of fractal analyses can be distinguished: discriminate between fractal and non-fractal patterns for diagnostic purposes, test for the effective presence of genuine persistent correlations in the series, provide an accurate estimation of the strength of these long-range dependencies, or identify the short-term process that accompanies a fractal pattern. Delignières et al. (2005) point out that different objectives require distinct strategies. This paper demonstrated how to distinguish between fractal and non-fractal empirical time series employing the open source software R.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix

lowPSD SPSS-Code for series X with T = 512 to obtain a PSD-estimate of β.

is the negative slope of the regression

SPECTRA /VARIABLES=X /CENTER /SAVE FREQ(f) P(SS). COMPUTE ln_f = LN(f). EXECUTE. COMPUTE ln_p = LN(SS_1). EXECUTE. COMPUTE filter_$=(T>1 and T<(512/2*1/8+2)). FILTER BY filter_$. REGRESSION /STATISTICS COEFF /DEPENDENT ln_p /METHOD=ENTER ln_f .

lowPSD SAS-Code for series X with T = 512 to obtain a PSD-estimate of β.

proc spectra data=data out=spec p s center; var X; run; data spec; set spec; T+1; run; data loglog; set spec; if FREQ=0 then delete; if T>(512/2*(1/8)+1) then delete; ln_f=log(FREQ); ln_p=log(S_01); keep ln_f ln_p; run; proc reg data=loglog; model ln_p=ln_f; run;

lowPSD R-Code for series X to obtain a PSD-estimate of β.

n <- length(x) spec <- spectrum(x, detrend=FALSE, demean=TRUE, taper=0) nr <- (n/2) * (1/8) specfreq <- spec$freq[1:nr] specspec <- spec$spec[1:nr] logfreq <- log(specfreq) logspec <- log(specspec) lmb <- lm(logspec cosim logfreq) b <- coef(lmb) beta=-b[2] plot (logfreq, logspec, type=“l”) abline(lmb) print(beta)

PSD R-Code for series X to obtain a PSD-estimate of β.

spec <- spectrum(x, detrend=FALSE, demean=TRUE, taper=0) specfreq <- spec$freq specspec <- spec$spec logfreq <- log(specfreq) logspec <- log(specspec) lmb <- lm(logspec cosim logfreq) b <- coef(lmb) beta=-b[2] plot (logfreq, logspec, type=“l”) abline(lmb) print(beta)

Fractal analyses with R

-

Step “Preparation”

Install R from http://www.r-project.org/

-

Install the packages fracdiff, fractal, tseries [Click install packages under the packages menu, select these packages and confirm with ok].

Some tips for comfortably working with R:

R commands can be typed directly in the R console after the symbol “>” (see Figures 3 and 4). To obtain the R output, just press [ENTER].

The easiest way to administer R commands is to open a new script [click data − new script] and write the commands there. You can enter one or more commands in the R console by selecting them and pressing [CTRL + R].

-

Step “Data Import in R”

Create an excel file (e.g., for one time series of length T = 500, type the name “x” in the first row of the first column, then type 500 observations in the subsequent rows of the column).

Save data in csv format [Excel: click save as, then activate save as type and choose CSV (Comma delimited)]. As a result, you obtain an excel file name.csv.

Open R and click data − change directory and choose the directory where you saved the file name.csv. Typing the command getwd() shows the current working directory of R.

Get the excel file name.csv into R by writing in the R console the command data=read.csv2(“name.csv”) (see Figure 4).

Choose the variable x from the frame data by typing x=data$x. Because the file name.csv and accordingly the R frame data consist of one variable saved in the first column, you can alternatively get the variable x using the command x=data[,1]. Note that the command data[2,] outputs the second row of the frame data.

-

Step “Performing fractal analyses”

Load the packages fracdiff, fractal, tseries [type the commands library (fracdiff), library (fractal), library(tseries)].

Load SSC and lowPSDwe (download the files SSC.R and lowPSDwe.R from http://www.psychologie.uni-heidelberg.de/projekte/zeitreihen/R_Code_Data_Files.html, then click read R-code from the data menu).

-

Type the following commands in the R console (see Figures 3 and 4) or write them in a script and submit by pressing [CTRL + R].

plot(x, ty=``l``) acf(x) adf.test(x) kpss.test(x) PSD(x) SSC(x) DFA(x, detrend=“bridge”, sum.order=1) fdSperio(x) fdGPH(x) FDWhittle(x) hurstSpec(x) fracdiff(x)

-

Step “ARFIMA analyses”

Compute AIC and BIC of different long and short-memory models (see Tables 2 and 3). The command AIC(fracdiff(x, nar = 2, nma = 2)) outputs the AIC of the ARFIMA (2, d, 2) model. The command AIC(arima(x, order=c(2,0,1))) calculates the AIC of the ARIMA (2, 0, 1) structure.

Estimate d of the model with the smallest AIC or BIC using the command summary(fracdiff(x, nar=0, nma=2)).

Compute a 0.95-confidence interval using the estimate of d and its SE:

References

- Aks D. J., Sprott J. C. (2003). The role of depth and 1/f dynamics in perceiving reversible figures. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol. Life Sci. 7, 161–180 10.1023/A:1021431631831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak P., Tang C., Wiesenfeld K. (1987). Self-organized criticality: an explanation of 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 381–384 10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran J. (1994). Statistics for Long-Memory Processes. New York: Chapman & Hall [Google Scholar]

- Box G. E. P., Jenkins G. M. (1970). Time Series Analysis, Forecasting and Control. San Francisco: Holden Day [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell P. J., Davis R. A. (2002). Introduction to Time Series and Forecasting. New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Ding M., Kelso J. A. S. (1997). Long memory processes (1/fa type) in human coordination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 4501–4504 10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.2253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Ding M., Kelso J. A. S. (2001). Origins of time errors in human sensorimotor coordination. J. Mot. Behav. 33, 3–8 10.1080/00222890109601897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C. F. (1996). A generalized fractionally integrated ARMA process. J. Time Ser. Anal. 2, 111–140 10.1111/j.1467-9892.1996.tb00268.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delignières D., Lemoine L., Torre K. (2004). Time intervals production in tapping oscillatory motion. Hum. Mov. Sci. 23, 87–103 10.1016/j.humov.2004.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delignières D., Ramdani S., Lemoine L., Torre K. (2006). Fractal analyses for short time series: a re-assessment of classical methods. J. Math. Psychol. 50, 525–544 10.1016/j.jmp.2006.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delignières D., Torre K., Lemoine L. (2005). Methodological issues in the application of monofractal analyses in psychological and behavioral research. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol. Life Sci. 9, 435–462 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M., Chen Y., Kelso J. A. S. (2002). Statistical analysis of timing errors. Brain Cogn. 48, 98–106 10.1006/brcg.2001.1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke A., Herman P., Bassingthwaighte J. B., Raymond G., Percival D., Cannon M. J., Balla I., Ikenyi C. (2000). Physiological time series: distinguishing fractal noises from motions. Pflügers Arch. 439, 403–415 10.1007/s004240050957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke A., Herman P., Kocsis L., Kozak L. R. (2002). Fractal characterization of complexity in temporal physiological signals. Physiol. Meas. 23, R1–R38 10.1088/0967-3334/23/1/301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilden D. L., Thornton T., Mallon M. W. (1995). 1/f noise in human cognition. Science 267, 1837–1839 10.1126/science.7892611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger C. W. J., Joyeux R. (1980). An introduction to long-range time series models and fractional differencing. J. Time Ser. Anal. 1, 15–30 10.1111/j.1467-9892.1980.tb00297.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haslett J., Raftery A. E. (1989). Space-time modelling with long-memory dependence: assessing Ireland’s wind power resource. Appl. Stat. 38, 1–50 10.2307/2347679 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorf J. M., Peng C. K. (1996). Multiscaled randomness: a possible source of 1/f noise in biology. Phys. Rev. E. Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics 54, 2154–2157 10.1103/PhysRevE.54.2154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorf J. M., Zemany L., Peng C. K., Goldberger A. L. (1999). Maturation of gait dynamics: Stride-to-stride variability and its temporal organization in children. J. Appl. Physiol. 86, 1040–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking J. R. M. (1981). Fractional differencing. Biometrika 68, 165–176 10.1093/biomet/68.1.165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking J. R. M. (1984). Modelling persistence in hydrological time series using fractional differencing. Water Resour. Res. 20, 1898–1908 10.1029/WR020i012p01898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst H. E. (1965). Long-Term Storage: An Experimental Study. London: Constable [Google Scholar]

- Jensen H. J. (1998). Self-Organized Criticality. Cambridge: University Press [Google Scholar]

- Linkenkaer-Hansen K. (2002). Self-Organized Criticality and Stochastic Resonance in the Human Brain. Dissertation, Helsinki University of Technology Laboratory of Biomedical Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot B. B., van Ness J. W. (1968). Fractional Brownian motions, fractional noises and applications. SIAM Rev. 10, 422–437 10.1137/1010093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot B. B., Wallis J. R. (1969). Computer experiments with fractional Gaussian noises. Water Resour. Res. 5, 228–267 10.1029/WR005i004p00917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norris P. R., Stein P. K., Cao H., Morris J. J., Jr. (2006) Heart rate multiscale entropy reflects reduced complexity and mortality in 285 patients with trauma. J. Crit. Care 21, 343. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C.-K., Mietus J., Hausdorff J. M., Havlin S., Stanley H. E., Goldberger A. L. (1993). Long-range anticorrelations and non-Gaussian behavior of the heartbeat. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1343–1346 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell F. (1992a). Maximum likelihood estimation of stationary univariate fractionally integrated time series models. J. Econom. 53, 165–188 10.1016/0304-4076(92)90084-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell F. (1992b). Modeling long-run behavior with the fractional ARFIMA model. J. Monet. Econ. 29, 277–302 10.1016/0304-3932(92)90016-U [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnitski T. (2012). Some critical aspects of fractality research. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol. Life Sci. 16, 137–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnytska T. (2010). Deterministic or stochastic trend: decision on the basis of the augmented Dickey-Fuller Test. Methodology 6, 83–92 [Google Scholar]

- Stadnytska T., Braun S., Werner J. (2010). Analyzing fractal dynamics employing R. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol. Life Sci. 14, 117–144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnytska T., Werner J. (2006). Sample size and accuracy of estimation of the fractional differencing parameter. Methodology 4, 135–144 [Google Scholar]

- Stroe-Kunold E., Stadnytska T., Werner J., Braun S. (2009). Estimating long -range dependence in time series: An evaluation of estimators implemented in R. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 909–923 10.3758/BRM.41.3.909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taqqu M. S., Teverovsky V. (1997). Robustness of Whittle-type estimators for time series with long range dependence. Stochastic Models 13, 723–757 10.1080/15326349708807449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton T. L., Gilden D. L. (2005). Provenance of correlation in psychological data. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 12, 409–441 10.3758/BF03193785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre K., Delignières D., Lemoine L. (2007). Detection of long-range dependence and estimation of fractal exponents through ARFIMA modeling. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 60, 85–106 10.1348/000711005X89513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre K., Wagenmakers E.-J. (2009). Theories and models for 1/fβ noise in human movement science. Hum. Mov. Sci. 28, 297–318 10.1016/j.humov.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden G. C., Holden J. G., Turvey M. T. (2003). Self-organization of cognitive performance. J. Exp. Psychol. 3, 331–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden G. C., Holden J. G., Turvey M. T. (2005). Human cognition and 1/f scaling. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 134, 117–123 10.1037/0096-3445.134.1.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers E.-J., Farrell S., Ratcliff R. (2004). Estimation and interpretation of 1/fa noise in human cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 11, 579–615 10.3758/BF03196615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner R. M. (1998). Spectral Analysis of Time-Series Data. New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]