Abstract

Curcumin (diferulolylmethane) is an anti-inflammatory phenolic compound found effective in preclinical models of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and in ulcerative colitis patients. Pharmacokinetics of curcumin and its poor systemic bioavailability suggest that it targets preferentially intestinal epithelial cells. The intestinal epithelium, an essential component of the gut innate defense mechanisms, is profoundly affected by IFN-γ, which can disrupt the epithelial barrier function, prevent epithelial cell migration and wound healing, and prime epithelial cells to express major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules and to serve as nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells. In this report we demonstrate that curcumin inhibits IFN-γ signaling in human and mouse colonocytes. Curcumin inhibited IFN-γ-induced gene transcription, including CII-TA, MHC-II genes (HLA-DRα, HLA-DPα1, HLA-DRβ1), and T cell chemokines (CXCL9, 10, and 11). Acutely, curcumin inhibited Stat1 binding to the GAS cis-element, prevented Stat1 nuclear translocation, and reduced Jak1 phosphorylation and phosphorylation of Stat1 at Tyr701. Longer exposure to curcumin led to endocytic internalization of IFNγRα followed by lysosomal fusion and degradation. In summary, curcumin acts as an IFN-γ signaling inhibitor in colonocytes with biphasic mechanisms of action, a phenomenon that may partially account for the beneficial effects of curcumin in experimental colitis and in human IBD.

Keywords: epithelial barrier, interferon gamma receptor, STAT1

idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as Crohn's disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic and relapsing inflammatory conditions of the gut. The most commonly accepted hypothesis for the pathogenesis of IBD is that exaggerated adaptive, T cell-mediated immune response to enteric bacteria develop in genetically susceptible hosts, with environmental factors precipitating the onset of disease (14, 37). Production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines is enhanced in IBD. One of the most prominent proinflammatory cytokines with profound effects on epithelial cells is IFN-γ. Elevated IFN-γ disrupts the epithelial barrier function by inducing tight junction internalization (7) and size-selective increase in permeability (45), prevents epithelial cell migration (27), impairs wound healing by causing endocytosis of β1-integrin containing focal adhesions and by preventing interenterocyte gap junction communication via connexin 43 (28, 43). All of these are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases (10). IFN-γ also primes intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) to express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules (11, 39) and to serve as nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells (APC). IEC isolated from IBD patients have been shown to coexpress costimulatory molecules (CD58, CD86, B7H) and to potently induce proliferation of CD4+ lymphocytes when cocultured (12).

Recently, there has been a growing interest in the use of curcumin in treatment and/or prevention of IBDs with multiple reports of benefit in chemically induced rodent models of IBD as well as in a clinical trial with UC patients (16). Many of the curcumin effects relate to its ability to suppress inflammation (18). However, poor systemic bioavailability following oral administration, as well as rapid metabolism, suggest that IEC may be the primary target of the compound's biological activity. On a molecular level, curcumin's anti-inflammatory activity has been attributed to inhibition of several transcription factors, especially NF-κB (31), AP-1 (5) and to the stimulation of PPARγ (20). More recently, the Jak/Stat pathway has been shown to also be targeted by curcumin in the microglia (22). Although NF-κB inhibition received a particular attention in the context of intestinal inflammation, data from IEC-specific knockout mice targeting the NF-κB pathway indicated that its limited activation is critical in the process of epithelial repair and restitution, and suggested that NF-κB inhibition alone cannot account for the beneficial effects of curcumin in the intestinal inflammatory conditions (21).

Curcumin has been shown in various animal models and human studies to be extremely safe even at very high doses (3). Up to 8 g daily administered to patients for 3 mo did not cause toxicity (9). In our previously published studies, dietary curcumin supplementation leading to colitis prevention resulted in millimolar concentrations within the colonic lumen with no observable toxicity (6, 26). However, in both humans and laboratory rodents, curcumin displays very low bioavailability with poor absorption and rapid metabolic elimination (3). The highest achieved peak serum concentration in the peripheral blood for a single oral dose (12 g) in human patients reached only 51.2 ng/ml (139 nM) (25). Although the gut epithelium can be exposed in vivo to large concentrations of curcumin, limited transepithelial flux and rapid metabolism likely determine the lack of curcumin's systemic toxicity.

In this report, we demonstrate that curcumin profoundly suppresses IFN-γ signaling in human and mouse colonocytes. Acutely, curcumin inhibits the Jak/Stat activation pathway by modulating Stat1 phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, DNA binding, and transcription of IFN-γ-inducible MHC-II genes and T cell chemokines. Curcumin treatment also leads to endocytosis of IFNγRα subunit and its lysosomal degradation. This not only represents a novel mechanism of mucosal protection provided by dietary curcumin but also describes a novel mode of regulation of IFN-γ signaling in intestinal epithelial cells via endocytic retrieval and lysosomal degradation of IFNγRα.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Curcumin, 98.05% pure and free of contaminating curcuminoids (demethoxy-curcumin and bis-demethoxy-curcumin), was obtained from ChromaDex (Irvine, CA). Human and mouse IFN-γ were obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Stat1 (p84/p91), Jak1 (HR-785), IFNγRα (C-20), Sp1 (PEP2), and TNFR1 rabbit polyclonal antibodies and ubiquitin Ub (P4D1) mouse monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). P4D1 antibody detects ubiquitin, polyubiquitin, and ubiquitinated proteins. Phospho-Stat1 (Tyr701). Phospho-Jak1 (Tyr1022/1023), phospho-SHP-2 (Tyr542), and SHP-2 rabbit polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). GAPDH mouse monoclonal antibody was obtained from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Anti-human transferrin receptor (CD71) mouse monoclonal antibody was from Becton-Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ), and anti-mouse goat polyclonal CD71 antibody was from Santa Cruz.

Cell culture.

T-84 cells (human colorectal carcinoma) were kindly provided by Declan McCole (University of California, San Diego, CA). Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 1% HEPES, 5% newborn calf serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO). YAMC cells (young adult mouse colonocytes) are conditionally immortalized mouse colonic intestinal epithelial cell line derived from the H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic “Immortomouse” (46) and were a generous gift from Dr. R. Whitehead (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). YAMC cells are propagated under permissive temperature (33°C) in the presence of IFN-γ (5 U/ml) and can be partially differentiated under nonpermissive conditions at 37°C in the absence of IFN-γ. YAMC cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, insulin (1 μg/ml), 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 U/ml penicillin. Before experiments, the medium was replaced with one without IFN-γ, and the cells were moved to 37°C for 48 h to allow them to differentiate. In some cases, cells were incubated with curcumin for 0–8 h with or without the addition of the proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone or the lysosomal degradation inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (both from Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO).

Curcumin uptake.

Cells were seeded in black, clear-bottom cell culture plates. At confluence, cells were treated with DMSO or 50 μM curcumin at 37°C or at 4°C. Cells were then washed three times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fluorescence was measured with Fluoroskan Ascent plate fluorometer and Fluoroskan software (Labsystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) by using 485-nm and 527-nm excitation and emission filters, respectively.

Live cell confocal imaging.

Subconfluent YAMC cells grown in Lab-Tek Chamber Slides (Nunc; Rochester, NY), were exposed to 50 μM curcumin or DMSO for 20 min. Cell were then washed with PBS and confocal z-sections were obtained with live cells by use of the Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope and Bio-Rad 1024ES confocal imaging system. Live cell imaging was a preferred method owing to the artifactual translocation of curcumin-associated fluorescence to the nucleus in fixed cell preparations.

Transfection.

T-84 cells were transfected (Amaxa Nucleofector; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) with a reporter construct driven by a tandem of IFN-γ activation sites (pGAS-Luc, Clontech; Mountain View, CA). The cells were treated with IFN-γ alone for 5 h or pretreated with 50 μM curcumin for 20 min; medium was then changed to containing IFN-γ and curcumin for 5 h. Cells were harvested in lysis buffer and 20 μl of the lysate was used for firefly luciferase assay (Promega, Madison, WI). The results were expressed as relative light units per microgram protein (evaluated with Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Real-time PCR.

Gene expression was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Total RNA (200 ng) was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and reverse-transcribed using the iScript kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Ten percent of the RT reaction was used for real-time PCR analysis for expression of HLA-DRA, HLA-DPA1, HLA-DRB1, CIITA, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, and IFNGR1. TBP (TATA-box binding protein) was used as an internal control. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was optimized and performed with primer/TaqMan probe sets from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), iQSupermix (Bio-Rad), and the iCycler optical PCR cycler (Bio-Rad). Resulting data were analyzed by the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method as means of relative quantitation of gene expression, normalized to an endogenous reference (TBP) and relative to a calibrator (normalized Ct value obtained from control samples), and expressed as 2−ΔΔCt (Applied Biosystems User Bulletin no. 2: Rev B “Relative Quantitation of Gene Expression”).

EMSA analysis of Stat1 binding to GAS and ISRE consensus elements.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as reported elsewhere (34). EMSA was performed for 20 min in RT in a 10-μl volume containing 5 μg nuclear protein and γ-32P-radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe. DNA-protein binding reactions were resolved on 8% DNA retardation gel, dried, and exposed to X-ray film; 100 × molar excess of unlabeled competitor probe was included in some reactions to demonstrate binding specificity. Double-stranded oligonucleotide probes were used: IFN-γ-activated sequence (GAS) 5′-AGCCTGATTTCCCCGAAATGACGGC′3 and IFN-stimulated regulatory element (ISRE) 5′-CCCTTCTGAGGAAACGAAACCAG′3. 5′-End-labeled probes were prepared with [γ-32P] ATP by use of T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) and were purified on G-25 columns (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ).

Stat1 immunofluorescence.

T-84 cells grown in Lab-Tek Chamber Slides (Nunc) were pretreated with DMSO or 50 μM curcumin for 20 min and then treated for 2 h with DMSO (control), IFN-γ (100 U/ml), or IFN-γ + 50 μM curcumin. Cells were fixed and labeled with Alexa-Fluor 647-labeled anti-Stat1 antibody (red) and counterstained with Sytox green (nuclear stain; Invitrogen).

Western blot analysis.

Cells grown and treated in 24-well plates were washed twice in cold PBS and then lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail or with 100 μl hot Laemmli sample buffer with β-mercaptoethanol. The lysates were sonicated for 10 s to shear the chromatin, loaded into 8% polyacrylamide gel, and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated with respective primary antibody overnight at 4°C, washed, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce).

Cell surface protein biotinylation.

T-84 cells were washed two times with ice-cold PBS and incubated with gentle agitation at 4°C for 30 min in PBS containing 1.2 mg/ml of sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin. Excess biotin was quenched by adding Tris and glycine (in PBS, pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 20 and 15 mM, respectively, and the cells were further incubated for 5 min at 4°C. The cells were then washed twice with cold Tris-buffered saline and harvested in ice-cold RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors cocktail (Pierce). Biotinylated cell surface proteins were isolated using immobilized streptavidin, and 125 μl of resin was used for 1 mg of solubilized membrane protein. The resin was incubated with the total lysate for 1 h at 4□°C with gentle agitation, pelleted, and washed five times with lysis buffer. The biotinylated proteins were eluted with 100 μl of SDS sample buffer containing 50 mM DTT by incubating for 5 min at 95°C. Ten microliters of the above samples were analyzed by Western blotting with total cell lysate used as a loading control.

Animals, diets, and colonocytes isolation.

Eight- to 10-wk-old BALB/c mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Custom diet based on NIH-31 formula and containing 0.1% curcumin was prepared by Harlan Teklad (Madison, WI). Mice were fed the control of curcumin-supplemented diet (three mice per group) for 4 days. After CO2 anesthesia and cervical dislocation, colons were harvested and processed for sequential colonocytes isolation. Briefly, colon was tied off at one end and everted on polyethylene tubing. Colons were then incubated with shaking at 37°C for three sequential 30-min cycles in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1.5 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM DTT. The three cell fractions were pooled, counted and tested for viability (Trypan blue exclusion; ViCell XR, Beckman-Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) and divided in half for surface biotinylation and assessment of IFNγRα protein expression or seeded in six-well plates and treated with 100 IU of recombinant murine IFN-γ for 10 min for the analysis of Stat-1 activation (see detailed methods above). All animal protocols and procedures were approved by the University of Arizona Animal Care and Use Committee.

RESULTS

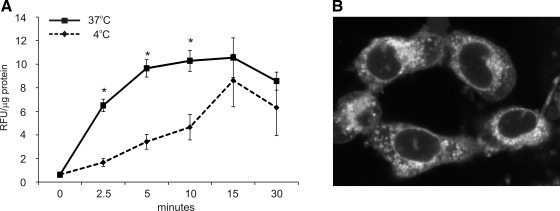

Curcumin uptake in colonic epithelial cells.

Curcumin is a naturally fluorescent compound with a fairly broad range of fluorescence but with excitation and emission maxima close to those of FITC (M. T. Midura-Kiela, unpublished observations). Curcumin uptake can be analyzed in live cells by fluorescence measurement. As depicted in Fig. 1A, curcumin is taken up by the colonocytes, reaching a plateau within 20 min. The decline in fluorescence after 30 min is likely an indicator of curcumin metabolism. Curcumin appeared to be taken up by a combination of passive diffusion (likely related to its high lipophilicity) and active endocytosis, since inhibition of the endocytic process at 4°C slowed down but did not completely prevent the intracellular accumulation of curcumin. Live confocal cell imaging shown in Fig. 1B (YAMC mouse colonocytes) shows primarily intracellular, but not plasmalemmal, accumulation of curcumin, with a majority of the fluorescence within a perinuclear vesicular compartment, without penetrating the nuclear envelope. More precise localization in a specific compartment remains technically challenging, since fixation of cells for colocalization studies results in artifactual translocation of curcumin to the nucleus.

Fig. 1.

A: curcumin uptake (50 μM, 0–30 min) was performed with T-84 cells at 37°C or 4°C. Similar results were obtained in conditionally immortalized mouse colonocytes [young adult mouse colonocytes (YAMC); not shown]. Cells treated with DMSO for respective durations were used for calculating background fluorescence. *Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between curcumin uptake at 37°C and 4°C at respective time points (Student's t-test; n = 6). B: z-section from live cell imaging of curcumin-loaded YAMC cells 20 min into 50 μM curcumin treatment.

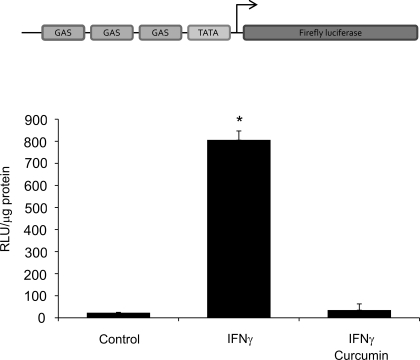

Curcumin inhibits IFN-γ stimulated transcription of a GAS-driven reporter gene expression.

To investigate the anti-inflammatory actions of curcumin and its mechanism in IEC, we undertook a “bottom-up” approach and first examined whether curcumin inhibits a “generic” IFN-γ-induced transcriptional response in colonic epithelial cells. T-84 cells were transfected with a reporter construct pGAS-Luc (GAS: interferon-γ-activated site). IFN-γ (100 U/ml; 5 h) significantly stimulated luciferase activity, whereas in cells cotreated with 50 μM curcumin this response was abolished (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

T-84 cells were nucleoporated with IFN-γ reporter construct pGAS-Luc (GAS) and treated with 100 U/ml IFN-γ for 5 h with and without 50 μM curcumin (administered 20 min prior to the addition of IFN-γ). Luciferase activity was measured with cell extract by using firefly luciferase assay kit and the results were calculated as relative light units (RLU) per μg protein. *Statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between reporter activity (Student's t-test; n = 3).

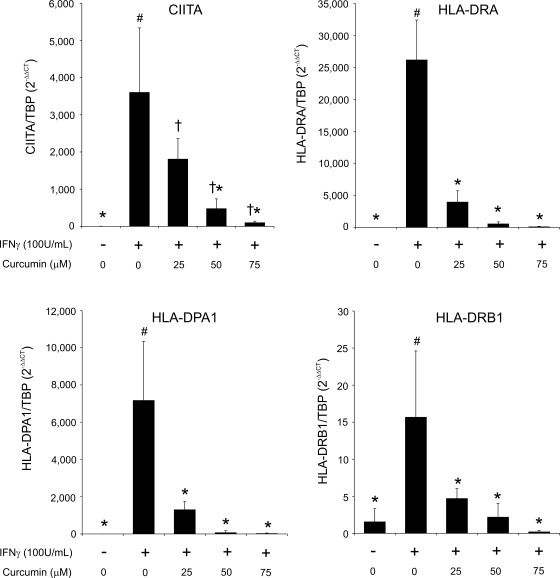

Curcumin inhibits upregulation of the class II transactivator CIITA and MHC-II genes in IFN-γ-treated colonocytes.

Next, we analyzed specific and clinically relevant IFN-γ target genes. IFN-γ stimulates expression of MHC class II (MHC-II) genes in colonic epithelial cells, which converts them into nonprofessional APCs that promote proinflammatory CD4+ T cell proliferation in IBD patients (12, 19). Therefore, it was of clinical relevance to verify whether curcumin is able to downregulate IFN-γ stimulated MHC-II gene expression in colonocytes. Quantitative RT-PCR results showed that curcumin was able to dose dependently downregulate IFN-γ stimulated expression of CIITA, a master regulator of MHC class II genes as well as the expression of HLA-DRA, HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DRB1 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the effects of curcumin on IFN-γ-induced MHC-II gene expression in T-84 cells. Cells were stimulated with 100 U/ml IFN-γ for 24 h with or without curcumin (25–75 μM; administered 20 min prior to the addition of IFN-γ). TBP was used as a reference gene. Different symbols next to bars indicate statistical significances (P ≤ 0.05) between groups [ANOVA followed by Fisher protected least significant difference (PLSD) post hoc test; n = 4].

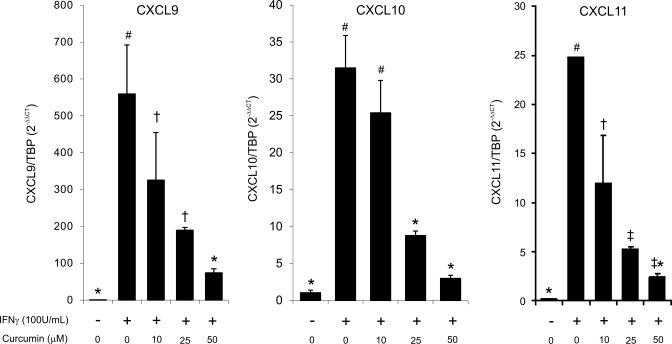

Curcumin reduces expression of IFN-γ-inducible lymphocyte chemoattractants in human colonic epithelial cells.

Three CXCR3 ligands [CXCL9 (Mig), CXCL10 (IP-10), and CXCL11 (I-TAC)] are potent T cell and NK cell chemoattractants produced by colonic epithelial cells in an IFN-γ-inducible fashion, with a profound role in the pathogenesis of IBD (42). Among the three chemokines, CXCL10 also inhibits intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and regulates crypt cell proliferation during acute colitis (40). In T-84 cells, IFN-γ rapidly and potently induced expression of the three chemokines, and curcumin dose dependently inhibited this increase (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the effects of curcumin on IFN-γ-induced expression of CXCR3 ligands. T-84 cells were pretreated with 25–75 μM of curcumin for 20 min prior to stimulation with IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 24 h. TBP was used as a reference gene. Different symbols next to bars indicate statistical significances (P ≤ 0.05) between groups (ANOVA followed by Fisher PLSD post hoc test; n = 4).

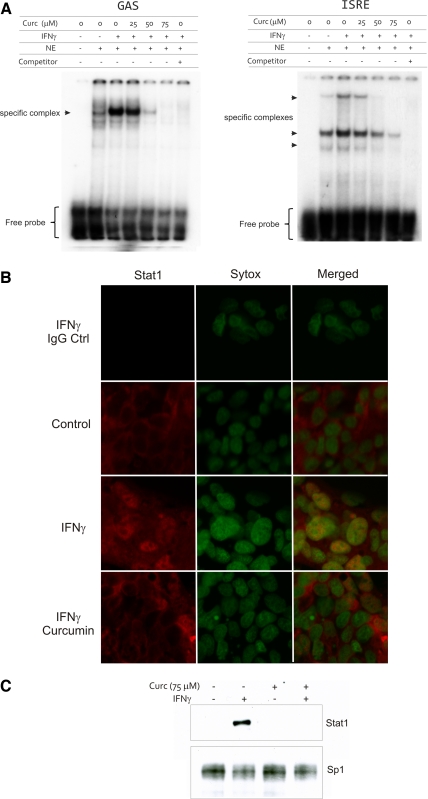

Curcumin inhibits Stat1 binding to the GAS and ISRE cis-elements and prevents IFN-γ-stimulated nuclear translocation of Stat1.

Binding of phosphorylated Stat1 homodimers to the GAS site within regulatory regions of IFN-γ-inducible gene promoters is essential for the induction of gene transcription. Moreover, IFN-γ promotes the formation of Stat1-Stat2 heterodimers, which associate with IRF-9 to form ISGF-3 and bind to the ISRE enhancer family. Stat1 has therefore a pivotal role in the biological response to both type I and II IFNs. Nuclear extracts were prepared from T-84 cells treated with IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 30 min and cotreated with DMSO or increasing concentrations of curcumin (25, 50, 75 μM). Curcumin downregulated Stat1 binding to the GAS and ISRE elements in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). Under steady-state conditions (cells treated with control medium with DMSO), all Stat1-associated immunofluorescence was cytoplasmic with no identifiable staining in the nuclei. Treatment of T-84 cells with 100 U/ml IFN-γ for 30 min led to Stat1 translocation to the nuclei in the majority of cells. In cells pretreated with curcumin (75 μM) followed by treatment with IFN-γ and curcumin for 2 h, no visible nuclear Stat1 was observed (Fig. 5B). We further verified this observation by Western blot analysis of Stat1 abundance in the nuclear extracts prepared from cells treated in an analogous way (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

EMSA analysis of nuclear protein binding to the GAS and IFN-stimulated regulatory element (ISRE) cis-elements. A: cells were treated with IFN-γ for 30 min without or with increasing concentrations of curcumin (25–75 μM; administered 20 min prior to the addition of IFN-γ). NE, nuclear extract; Competitor, 100 × excess of unlabeled probe. Excess of labeled probe indicated at the bottom. Immunofluorescence (B) and Western blot (C) analysis of Stat1 nuclear translocation in T-84 cells. Cells were treated with curcumin (75 μM) and IFN-γ in a way analogous to that used in EMSA analysis (A). Green nuclear staining is Sytox green. Red staining represents Stat1 (Alexa647). Topmost panels show negative (rabbit IgG) control. Sp1 was used as a loading control for Western blot detection of total nuclear Stat1 (C).

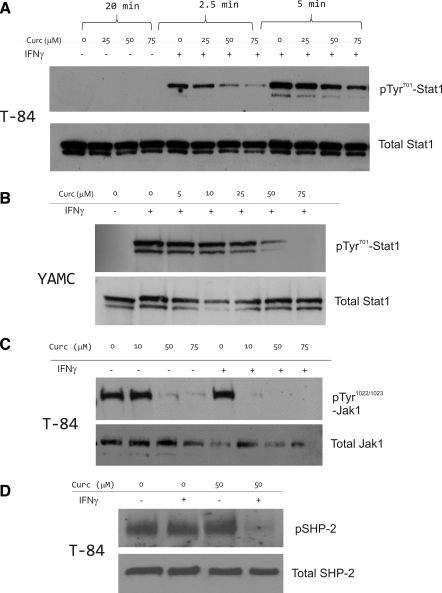

Curcumin inhibits IFN-γ-stimulated Stat1 phosphorylation at Tyr701 and Jak1 at Tyr1022/1023.

Phosphorylation at Tyr701 and subsequent dimerization of Stat1 are required for translocation to the nucleus. Cells pretreated with curcumin (25–75 μM) for 20 min followed by treatment with IFN-γ and curcumin showed inhibition of phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner. This effect was visible after only 2.5 min of IFN-γ treatment and was more pronounced after 5 min (Fig. 6A). To verify that this was not specific to T-84 carcinoma cells, we obtained analogous results in conditionally immortalized YAMC cells (Fig. 6B). Since Stat1 phosphorylation depends on the transphosphorylation of Jak1 and Jak2, we also investigated whether the inhibitory effect of curcumin was due to the suppression of Jak1 activation. Interestingly, in T-84 cells, Jak1 was constitutively phosphorylated at Tyr1022/1023, and IFN-γ only moderately increased pTyr1022/1023-Jak1 abundance (Fig. 6C). Curcumin reduced both the constitutive and IFN-γ-induced phosphorylation of Jak1 at this critical Tyr residue. We concluded that curcumin inhibits Jak-Stat signaling pathway during an acute (within minutes) exposure to IFN-γ.

Fig. 6.

Western blot analysis of the effects of IFN-γ and curcumin on phosphorylation of Stat1 (pTyr701), Jak1 (pTyr1022), and SHP-2 (pTyr542). Respective total protein was analyzed as loading control. Cells grown in 24-well plates were harvested in 100 μl hot Laemmli sample buffer, and 20 μl was used for electrophoresis. A: T-84 cells were pretreated with indicated concentrations of curcumin for 20 min prior to stimulation with IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 2.5 or 5 min. B: inhibition of Stat1 activation in in YAMC cells. YAMC cells were treated with curcumin (10–75 μM) for 20 min as indicated and/or treated with murine (m)IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 10 min. C: inhibition of Jak1 activation in T-84 cells. Cells were treated in a way analogous to A, but with 10-min stimulation with IFN-γ. D: effects of curcumin and IFN-γ on SHP-2 activation in T-84 cells. Cells were pretreated with 50 μM curcumin for 20 min prior to 10-min stimulation with IFN-γ (100 U/ml).

SHP-2 is an unlikely mediator of the inhibitory effects of curcumin on Jak-Stat signaling in colonic epithelial cells.

Ubiquitously expressed SHP-2 is a cytosolic protein tyrosine phosphatase containing Src homology 2 (SH2) domain. It is activated by phosphorylation of two tyrosine residues, with Tyr542 being the major and Tyr580 the minor phosphorylation site (32). Activated SHP-2 rapidly translocates to lipid rafts and directly dephosphorylates tyrosine-phosphorylated signaling molecules such as JAKs and STATs (23). Western blot analysis indicated slight upregulation of SHP-2 phosphorylation in T-84 whole cell lysate after curcumin treatment (Fig. 6D). However, in cells cotreated with IFN-γ and curcumin, pTyr542-SHP-2 was nearly undetectable (Fig. 6D). This suggests that, in colonic epithelial cells, SHP-2 is unlikely to contribute to the inhibitory effects of curcumin on the classical IFN-γ signaling pathway.

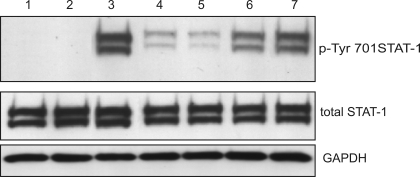

Pretreatment and continued exposure of cells to curcumin are required for the optimal inhibition of Stat1 activation.

To determine to optimal modality of treatment, we varied the pretreatment and treatment conditions and utilized Tyr701 Stat1 status as a reporter of IFN-γ signaling pathway. Curcumin alone had no effects, whereas IFN-γ alone rapidly and significantly increased the amounts of pTyr701Stat1 (Fig. 7, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). Pretreatment with curcumin followed by cotreatment with IFN-γ effectively reduced pTyr701Stat1 (Fig. 7, lane 4). Similar effect was observed when medium was not changed after curcumin pretreatment and IFN-γ was added to the existing medium (Fig. 7, lane 5). Pretreatment with curcumin followed by exposure to IFN-γ alone, as well as coexposure to curcumin and IFN-γ were not sufficient for the full extent of inhibition of Stat1 activation (Fig. 7, lanes 6 and 7, respectively). These studies suggest that continuous exposure to curcumin is necessary to achieve the effect. Moreover, since we observed no effects of curcumin on Stat1 activation when cells were simultaneously exposed to curcumin and IFN-γ (no pretreatment; Fig. 7, lane 7), we could indirectly conclude that under these short-term conditions, curcumin does not affect IFN-γ receptor binding or the initiation of the downstream responses.

Fig. 7.

Western blot analysis of Stat1 activation (pTyr701) with different modalities of treatment (YAMC cells). Cell were treated with 75 μM curcumin for 20 min and/or 100 U/ml mIFN-γ for 10 min thereafter. Lane 1: DMSO treated control cells. Lane 2: cells treated with curcumin alone for 20 min. Lane 3: cells treated with DMSO and IFN-γ. Lane 4: cells pretreated with curcumin, then medium changed to one containing curcumin and IFN-γ. Lane 5: cells pretreated with curcumin, then IFN-γ added to existing medium. Lane 6: cells pretreated with curcumin, then medium changed to one containing IFN-γ alone. Lane 7: curcumin and IFN-γ applied at the same time (no pretreatment).

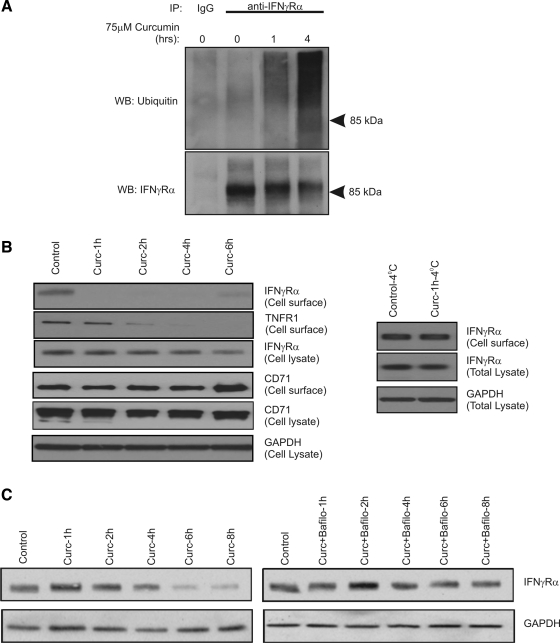

Extended exposure to curcumin leads to ubiquitination, internalization, and lysosomal degradation of IFNγRa.

We demonstrated that curcumin induced ubiquitination of IFNγRα by immunoprecipitating the receptor followed by Western blotting with ubiquitin-specific antibody (Fig. 8A). Ubiquitination coincided with a decrease of IFNγRα abundance on the plasma membrane by cell surface biotinylation (Fig. 8B). The loss of cell surface expression of IFNγRα in curcumin-treated cells could be prevented by exposing the cells to curcumin at 4°C, thus suggesting active endocytosis of the receptor (Fig. 8B, right). Interestingly, curcumin also affected surface expression of TNFR1 protein, but not that of transferrin receptor (CD71; Fig. 8B). Over time, a portion of the IFNγRα receptor recycled to the plasma membrane, albeit never reaching the levels observed in control cells. This could be explained by the progressive metabolism and inactivation of curcumin by the epithelial cells and sustained synthesis of the receptor since curcumin did not affect the expression of IFNGR1 mRNA (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Curcumin induces ubiquitination, internalization, and lysosomal degradation of IFNγRα. A: total cell lysates with T-84 cells treated with 75 μM curcumin for 0–4 h were immunoprecipitated (IP) with control IgG or anti-IFNγRα antibody. The precipitated protein was analyzed with ubiquitin-specific or IFNγRα-specific antibody (loading control) by Western blotting (WB). B: cell surface biotinylation performed in T-84 cells treated with 75 μM curcumin at 37°C (1–8 h; left) or 4°C (1 h; right). GAPDH or IFNγRα were analyzed in the total cell lysate as input controls. C: degradation of total cellular IFNγRα protein in T-84 cells treated with 75 μM curcumin for 1–8 h. Analysis was performed in the absence (left) or presence of the lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (right; see materials and methods).

Since ubiquitination and endocytic retrieval lead in certain cases to lysosomal fusion and lysosomal proteolytic degradation, we analyzed the abundance of total cellular IFNγRα in T-84 cells treated with curcumin for 1–8 h. We verified that such incubation time with curcumin in concentrations up to 75 μM did not result in change in cellular viability (with Trypan blue exclusion and adenylate kinase release assays; not shown). Curcumin-treated cells showed a gradual and marked decrease in the total IFNγRα protein levels after 4 to 8 h, time points later than those showed earlier as sufficient for ubiquitination and endocytosis (Fig. 8C, left). Inhibition of vacuolar H+-ATPase with bafilomycin A1 reversed the effects of curcumin on IFNγRα protein degradation (Fig. 8C, right). There was no effect of proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone on curcumin-induced degradation of IFNγRα (data not shown). Therefore, we concluded that long-term (1–8 h) exposure of epithelial cells to curcumin induces IFNγRα ubiquitination, internalization, and lysosomal degradation (a classical receptor endocytic pathway).

Dietary curcumin affects cell surface expression of IFNγRα and IFN-γ-induced Stat1 activation in vivo.

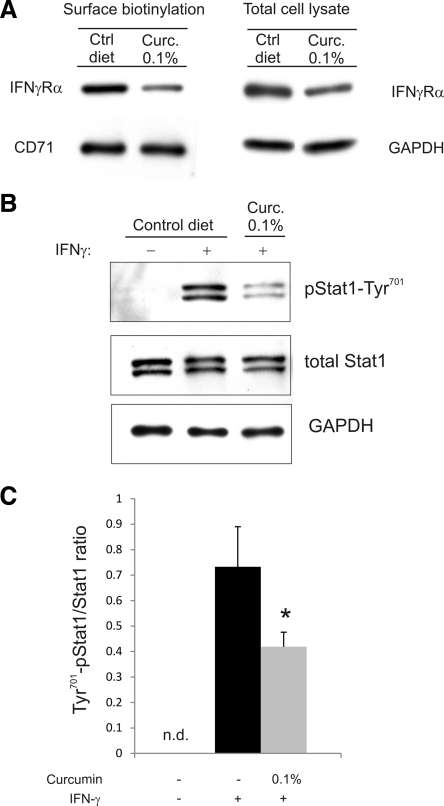

To confirm our in vitro findings, BALB/c mice were fed control or curcumin-supplemented diet at a concentration previously shown to reduce the symptoms of colitis in IL-10−/− mice, although it did not significantly alter IFN-γ release in colonic explant culture (26). Surface biotinylation performed with isolated colonocytes showed significantly decreased expression of IFNγRα protein on the plasma membrane and moderately reduced level of total IFNγRα in cell lysate, without concomitant changes in the surface expression of the transferrin receptor (CD71; Fig. 9A). Moreover, colonocytes from mice fed curcumin-supplemented diet responded significantly less robustly to 100 IU/ml IFN-γ, as measured by Tyr701 Stat1 abundance in total cell lysate (Fig. 9, B and C).

Fig. 9.

Dietary curcumin reduces surface expression IFNγRα and IFN-γ-induced Stat1 activation in colonic epithelial cells in vivo. A: cell surface and total cell lysate expression of IFNγRα in colonocytes isolated from mice fed control (Ctrl) or 0.1% curcumin-supplemented (Curc. 0.1%) diets. Transferrin receptor (CD71) was used as a loading control for surface protein, and GAPDH for total cell lysates. Image represents a representative Western blot with similar results obtained from 3 mice in each group. B: isolated colonocytes were plated and treated for 10 min with 100 IU murine recombinant IFN-γ. Cell lysates were analyzed for expression of Tyr701-pStat1, total Stat1, and GAPDH. C: summary of data presented in B (n = 3; n.d., not detected). *Statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05; Student's t-test) between colonocytes isolated from control mice and curcumin-fed mice.

DISCUSSION

The inhibitory effects of curcumin on major inflammatory pathways and mediators like NF-κB, COX-2, LOX, TNF-α, and IFN-γ and its safety profile suggest that it may be a viable option in the treatment of IBD (17). Despite large number of recent publications, its general mechanism of action remains poorly understood. Low bioavailability of orally administered curcumin in tissues outside of the gastrointestinal tract points to epithelial cells as the primary target of curcumin. Consistent with this hypothesis, curcumin has been proven effective in several animal models of IBD relying on epithelial injury, whereas relatively small effect of the compound was observed in immune-based model offered by IL-10−/− mice (26). In this report, we tested the possibility that the beneficial effects of curcumin in IBD may be attributed in part to the suppression of IFN-γ signaling in colonic epithelial cells. The exclusively in vitro approach was dictated by the fact that in mouse models of colitis curcumin reduces colonic expression of IFN-γ (44, 47), a phenomenon that would preclude accurate conclusions regarding downstream signaling events.

We took a bottom-up approach starting with a description of inhibition of generic transcriptional response to IFN-γ and moving up to describe target genes and proteins in the signaling cascade. Although in vivo, colonic epithelial cells can be exposed to millimolar concentrations of curcumin with no side effects (26), carcinoma cell lines widely used and accepted as models of human colonic epithelia, can be selectively targeted by the cytotoxic effects of curcumin (38). We therefore took precautions to use concentrations of the drug and incubation time carefully selected as not resulting in discernable toxicity. We also confirmed our key observations in conditionally immortalized mouse YAMC colonocytes.

We demonstrated that curcumin inhibits IFN-γ-induced expression of CIITA and three key MHC-II genes expressed by T-84 cells, as well as three CXCR3 ligands: CXCL9, 10, and 11. All of these genes have been implicated in the epithelial cell dysfunction and IBD pathogenesis. The three chemokines, CXCL9 (Mig), CXCL10 (IP-10), and CXCL11 (I-TAC), are the members of the family of ELR-CXC chemokines and bind the same CXCR3 receptor. They are potent chemoattractants of activated T cells and NK cells and are produced and secreted by colonic epithelial cells in an IFN-γ-inducible fashion. Several studies have demonstrated a pathogenic role of CXCR3 and its ligands in many human inflammatory diseases, and they are considered as viable therapeutic targets in IBD (15, 17, 29). CXCL9 is upregulated in IBD, and its polymorphisms have been associated with the early onset of pediatric CD (2). CXCL10 is elevated in the mucosa of UC patients (5) and a fully human anti-CXCL10 monoclonal antibody, MDX-1100, is being tested in clinical trials with a promise of the reduction of the disease severity in UC. Interestingly, CXCL10 seems to affect the survival of parenchymal cells of the colon more than the infiltration of inflammatory cells. In the dextran sulfate sodium-induced epithelial injury model, the neutralization of CXCL10 protected the mice from gut ulceration and promoted the survival of crypt cells and reepithelialization, ultimately leading to the protection from the injury (20).

IFN-γ has profound effects on epithelial integrity and promotes barrier dysfunction and increases epithelial permeability via multiple mechanisms (1, 8, 35). Curcumin has been reported to prevent increased permeability induced by TNF or IL-1β in Caco-2 cell monolayers (2, 33). In our hands, T-84 cells grown in tight (2,000–3,000 Ω·cm2) monolayers required a minimum 72 h of exposure to IFN-γ to induce a significant change in transepithelial resistance (data not shown). Such long exposure of T-84 carcinoma cells to curcumin induced cytotoxicity and prevented us from studying the effects of curcumin on IFN-γ-stimulated epithelial permeability.

Inhibition of IFN-γ-stimulated expression of the clinically relevant proinflammatory genes, such as MHC-II molecules and CXCR3 ligands, prompted further investigation of curcumin's mechanisms of action in colonic epithelial cells. EMSA results showed that curcumin inhibits Stat1 dimers binding to the DNA to both IFN-γ responsive GAS and ISRE elements. The latter was likely due to the cross-talk between IFN-γ receptor activation and target genes of the type I IFN pathway and the pivotal role of Stat1 in the biological response to both type I and II IFNs (41). IFN-γ also promotes the formation of Stat1-Stat2 heterodimers, which associate with IRF-9 to form ISGF-3 and bind to the ISRE enhancer family. Our results also demonstrated that curcumin inhibits IFN-γ stimulated Stat1 phosphorylation at Tyr701 and its translocation to the nucleus and confirmed inhibition of the upstream Jak1 activity as determined by its decreased phosphorylation at Tyr1022/1023.

Several phosphatases have been implicated in the inactivation of the cytokine receptors and Jaks including SHP-2. SHP-2 dephosphorylates both activated cytokine receptors and Jaks via a direct association of its SH2 domains with phosphotyrosine residues (4). SHP-2 has been reported to mediate inhibitory effects of curcumin on Jak-Stat pathway in the brain microglia (23). In colonic epithelial cells, curcumin alone slightly stimulated SHP-2 activity judging by a very moderate increase in pTyr542-SHP-2 abundance. This correlated with the inhibition of constitutive phosphorylation of Jak1 at pTyr1022. However, SHP-2 activity was dramatically decreased in cells cotreated with curcumin and IFN-γ, thus suggesting that the role of SHP-2 in mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin may be cell type dependent.

In addition to the rapid effects of curcumin on Jak-Stat signaling appearing within minutes of IFN-γ stimulation, we observed more chronic effects of the compound (within 1–8 h) on the ligand-binding subunit of IFN-γ receptor complex, IFNγRα. Treatment with curcumin induced its ubiquitination, endocytic retrieval, and lysosomal degradation. Although ubiquitin-dependent lysosomal degradation has been described for IFN-α/β receptor 1 (24), only one report demonstrated similar mechanism for IFNγRα (30). In that study, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus proteins K3 and K5 specifically targeted IFNγRα and induced its ubiquitination, endocytosis, and degradation, resulting in downregulation of IFNγRα surface expression and, thereby, inhibition of IFN-γ action (30). Although this likely represents an important and previously unappreciated means of terminating the response to IFN-γ, the precise mechanisms of this phenomenon remain unknown. The physiological and pathophysiological role and potential consequences of disruption of this pathway in epithelial and immune cells also remain to be elucidated. Another important question is whether such mechanism of curcumin's action is specific to IFN-γ receptor. Curcumin has a very diverse and extensive list of target proteins and signaling pathways (15). The overarching mechanism of curcumin action appears to be an induction of “anergy” or relative unresponsiveness to extracellular stimuli. Although it likely oversimplifies the effects of curcumin, it is possible that reduction of plasma membrane cellular receptors for a variety of inflammatory mediators may significantly contribute to the protective effects of curcumin in many inflammatory states. Supportive of this nonspecific effect is our observation that, in parallel with IFNγRα, TNFR1 also follows a similar pattern of reduction at the epithelial cell surface. However, analysis of surface expression of transferrin receptor (TfR1; CD71) in both mouse and human cells did not indicate a significant effect of curcumin. Transferrin receptor is known to be dynamically regulated by endocytosis (36); therefore our finding that it remained stable at the plasma membrane in curcumin-treated cells suggests at least some degree of specificity.

Another important observation from our studies is related to the most effective treatment modality. Curcumin was most effective as Jak-Stat inhibitor when cells were pretreated with the compound and when curcumin was present during the cytokine stimulation. Moreover, the effects of curcumin on IFNγRα endocytosis were transient, possibly because of a combination of curcumin metabolism and uninhibited synthesis of IFNγRα mRNA. These findings are further highlighted by the clinical trial with UC patients who experienced increased relapse rate when curcumin was switched to placebo (16). These results further suggest that the clinical potential of curcumin is in the prevention of relapse and that compliant intake would be critical to maintain remission.

In conclusion, our results describe a new dual mechanism of inhibition of IFN-γ signaling. Our novel observations likely represent a major mechanism of epithelial protection in intestinal inflammation leading to improved barrier function, epithelial restitution, and protection from relapse in UC.

GRANTS

This investigation was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 5R01DK067286 (to P. R. Kiela).

DISCLOSURES

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Al-Sadi R, Boivin M, Ma T. Mechanism of cytokine modulation of epithelial tight junction barrier. Front Biosci 14: 2765–2778, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al-Sadi RM, Ma TY. IL-1beta causes an increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J Immunol 178: 4641–4649, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm 4: 807–818, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker SJ, Rane SG, Reddy EP. Hematopoietic cytokine receptor signaling. Oncogene 26: 6724–6737, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balasubramanian S, Eckert RL. Curcumin suppresses AP1 transcription factor-dependent differentiation and activates apoptosis in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Biol Chem 282: 6707–6715, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Billerey-Larmonier C, Uno JK, Larmonier N, Midura AJ, Timmermann B, Ghishan FK, Kiela PR. Protective effects of dietary curcumin in mouse model of chemically induced colitis are strain dependent. Inflamm Bowel Dis 14: 780–793, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruewer M, Luegering A, Kucharzik T, Parkos CA, Madara JL, Hopkins AM, Nusrat A. Proinflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis-independent mechanisms. J Immunol 171: 6164–6172, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Capaldo CT, Nusrat A. Cytokine regulation of tight junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788: 864–871, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng AL, Hsu CH, Lin JK, Hsu MM, Ho YF, Shen TS, Ko JY, Lin JT, Lin BR, Ming-Shiang W, Yu HS, Jee SH, Chen GS, Chen TM, Chen CA, Lai MK, Pu YS, Pan MH, Wang YJ, Tsai CC, Hsieh CY. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res 21: 2895–2900, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiba H, Kojima T, Osanai M, Sawada N. The significance of interferon-gamma-triggered internalization of tight-junction proteins in inflammatory bowel disease. Sci STKE 2006: pe1, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colgan SP, Parkos CA, Matthews JB, D'Andrea L, Awtrey CS, Lichtman AH, Delp-Archer C, Madara JL. Interferon-gamma induces a cell surface phenotype switch on T84 intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 267: C402–C410, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dotan I, Allez M, Nakazawa A, Brimnes J, Schulder-Katz M, Mayer L. Intestinal epithelial cells from inflammatory bowel disease patients preferentially stimulate CD4+ T cells to proliferate and secrete interferon-γ. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1630–G1640, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duchmann R, Kaiser I, Hermann E, Mayet W, Ewe K, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. Tolerance exists towards resident intestinal flora but is broken in active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Clin Exp Immunol 102: 448–455, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Epstein J, Sanderson IR, Macdonald TT. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent: the evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies. Br J Nutr 103: 1545–1557, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanai H, Iida T, Takeuchi K, Watanabe F, Maruyama Y, Andoh A, Tsujikawa T, Fujiyama Y, Mitsuyama K, Sata M, Yamada M, Iwaoka Y, Kanke K, Hiraishi H, Hirayama K, Arai H, Yoshii S, Uchijima M, Nagata T, Koide Y. Curcumin maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4: 1502–1506, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hanai H, Sugimoto K. Curcumin has bright prospects for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharm Des 15: 2087–2094, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hatcher H, Planalp R, Cho J, Torti FM, Torti SV. Curcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 1631–1652, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hershberg RM, Mayer LF. Antigen processing and presentation by intestinal epithelial cells — polarity and complexity. Immunol Today 21: 123–128, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jacob A, Wu R, Zhou M, Wang P. Mechanism of the anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin: PPAR-gamma activation. PPAR Res 2007: 89369, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karrasch T, Jobin C. NF-kappaB and the intestine: friend or foe? Inflamm Bowel Dis 14: 114–124, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim HY, Park EJ, Joe EH, Jou I. Curcumin suppresses Janus kinase-STAT inflammatory signaling through activation of Src homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2 in brain microglia. J Immunol 171: 6072–6079, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim HY, Park SJ, Joe EH, Jou I. Raft-mediated Src homology 2 domain-containing proteintyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP-2) regulation in microglia. J Biol Chem 281: 11872–11878, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kumar KG, Barriere H, Carbone CJ, Liu J, Swaminathan G, Xu P, Li Y, Baker DP, Peng J, Lukacs GL, Fuchs SY. Site-specific ubiquitination exposes a linear motif to promote interferon-alpha receptor endocytosis. J Cell Biol 179: 935–950, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lao CD, Ruffin MT, 4th, Normolle D, Heath DD, Murray SI, Bailey JM, Boggs ME, Crowell J, Rock CL, Brenner DE. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement Altern Med 6: 10, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larmonier CB, Uno JK, Lee KM, Karrasch T, Laubitz D, Thurston R, Midura-Kiela MT, Ghishan FK, Sartor RB, Jobin C, Kiela PR. Limited effects of dietary curcumin on Th-1 driven colitis in IL-10 deficient mice suggest an IL-10-dependent mechanism of protection. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G1079–G1091, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leaphart CL, Dai S, Gribar SC, Richardson W, Ozolek J, Shi XH, Bruns JR, Branca M, Li J, Weisz OA, Sodhi C, Hackam DJ. Interferon-γ inhibits enterocyte migration by reversibly displacing connexin43 from lipid rafts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G559–G569, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leaphart CL, Qureshi F, Cetin S, Li J, Dubowski T, Baty C, Beer-Stolz D, Guo F, Murray SA, Hackam DJ. Interferon-gamma inhibits intestinal restitution by preventing gap junction communication between enterocytes. Gastroenterology 132: 2395–2411, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee MT, Chen FY, Huang HW. Energetics of pore formation induced by membrane active peptides. Biochemistry 43: 3590–3599, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Q, Means R, Lang S, Jung JU. Downregulation of gamma interferon receptor 1 by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K3 and K5. J Virol 81: 2117–2127, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin JK. Molecular targets of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol 595: 227–243, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu W, Gong D, Bar-Sagi D, Cole PA. Site-specific incorporation of a phosphotyrosine mimetic reveals a role for tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-2 in cell signaling. Mol Cell 8: 759–769, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma TY, Iwamoto GK, Hoa NT, Akotia V, Pedram A, Boivin MA, Said HM. TNF-α-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability requires NF-kappa B activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 286: G367–G376, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Majewski PM, Thurston RD, Ramalingam R, Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. Cooperative role of NF-κB and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) in the TNF-induced inhibition of PHEX expression in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 285: 34828–34838, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marchiando AM, Graham WV, Turner JR. Epithelial barriers in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Pathol 5: 119–144, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mayle KM, Le AM, Kamei DT. The intracellular trafficking pathway of transferrin. Biochim Biophys Acta doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mow WS, Vasiliauskas EA, Lin YC, Fleshner PR, Papadakis KA, Taylor KD, Landers CJ, Abreu-Martin MT, Rotter JI, Yang H, Targan SR. Association of antibody responses to microbial antigens and complications of small bowel Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 126: 414–424, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ravindran J, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin and cancer cells: how many ways can curry kill tumor cells selectively? AAPS J 11: 495–510, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruemmele FM, Gurbindo C, Mansour AM, Marchand R, Levy E, Seidman EG. Effects of interferon gamma on growth, apoptosis, and MHC class II expression of immature rat intestinal crypt (IEC-6) cells. J Cell Physiol 176: 120–126, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sasaki S, Yoneyama H, Suzuki K, Suriki H, Aiba T, Watanabe S, Kawauchi Y, Kawachi H, Shimizu F, Matsushima K, Asakura H, Narumi S. Blockade of CXCL10 protects mice from acute colitis and enhances crypt cell survival. Eur J Immunol 32: 3197–3205, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem 282: 20059–20063, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Singh UP, Venkataraman C, Singh R, Lillard JW., Jr CXCR3 axis: role in inflammatory bowel disease and its therapeutic implication. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 7: 111–123, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tong Q, Vassilieva EV, Ivanov AI, Wang Z, Brown GT, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. Interferon-gamma inhibits T84 epithelial cell migration by redirecting transcytosis of beta1 integrin from the migrating leading edge. J Immunol 175: 4030–4038, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ung VY, Foshaug RR, MacFarlane SM, Churchill TA, Doyle JS, Sydora BC, Fedorak RN. Oral administration of curcumin emulsified in carboxymethyl cellulose has a potent anti-inflammatory effect in the IL-10 gene-deficient mouse model of IBD. Dig Dis Sci 55: 1272–1277, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watson CJ, Hoare CJ, Garrod DR, Carlson GL, Warhurst G. Interferon-gamma selectively increases epithelial permeability to large molecules by activating different populations of paracellular pores. J Cell Sci 118: 5221–5230, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whitehead RH, VanEeden PE, Noble MD, Ataliotis P, Jat PS. Establishment of conditionally immortalized epithelial cell lines from both colon and small intestine of adult H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 587–591, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang M, Deng CS, Zheng JJ, Xia J. Curcumin regulated shift from Th1 to Th2 in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced chronic colitis. Acta Pharmacol Sin 27: 1071–1077, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]