Abstract

Oncolytic herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) represent a novel frontier against tumors resistant to standard therapies, like glioblastoma (GBM). The oncolytic HSVs that entered clinical trials so far showed encouraging results; however, they are marred by the fact that they are highly attenuated. We engineered HSVs that maintain unimpaired lytic efficacy and specifically target cells that express tumor-specific receptors, thus limiting the cytotoxicity only to cancer cells, and leaving unharmed the neighboring tissues. We report on the safety and efficacy in a high-grade glioma (HGG) model of R-LM113, an HSV recombinant retargeted to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), frequently expressed in GBMs. We demonstrated that R-LM113 is safe in vivo as it does not cause encephalitis when intracranially injected in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, extremely sensitive to wild-type HSV. The efficacy of R-LM113 was assessed in a platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced infiltrative glioma model engineered to express HER2 and transplanted intracranially in adult NOD/SCID mice. Mice injected with HER2-engineered glioma cells infected with R-LM113 showed a doubled survival time compared with mice injected with uninfected cells. A doubling in survival time from the beginning of treatment was obtained also when R-LM113 was administered into already established tumors. These data demonstrate the efficacy of R-LM113 in thwarting tumor growth.

Introduction

High-grade gliomas (HGGs) are the most common malignant brain tumors in adults. The most aggressive form, glioblastoma (GBM), has an incidence of 3 cases/year/100,000 persons and is one of the most fatal cancers.1 With the advent of temozolomide in combination with radiotherapy, survival merely improved from 12.1 to 14.6 months.2 This modest improvement, compared with that achieved for other cancers, emphasizes the lack of efficacy of standard treatments. These are in fact thwarted by the chemo- and radioresistance of HGG and by their infiltrative ability that makes surgical eradication generally ineffective. Moreover standard cancer therapy lacks specificity, often resulting in clinically significant cytotoxic effects on normal tissues. Currently, the main focus is, therefore, the development of novel and more efficient anti-HGG agents able to destroy infiltrating tumor cells, sparing the surrounding healthy tissue.

An innovative strategy against tumors exploits replication-competent viruses to infect and kill cancer cells (oncolytic virotherapy). In particular herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) emerges as a good candidate for several reasons: it is a mild pathogen in humans, it does not integrate into the host genome, it lyses the host cell following replication and, in a worst-case scenario, unwanted infection can be controlled by acyclovir. HSV-1 large genome is easily amenable to genetic engineering and provides ample space for the insertion of heterologous genes.3,4 The HSVs that so far entered clinical trials are marred by the fact that they are overattenuated, and safety was achieved at the expenses of potency. To overcome these limits the last generation oncolytic HSVs preserve the full lytic ability typical of wild-type viruses, and gain their cancer specificity from genetic modifications that enable them to infect only the cells of choice. To this end, the virus tropism is modified and the viruses are retargeted to receptors specifically overexpressed in cancer cells. Concomitantly, the viruses are detargeted from their natural receptors, and are completely unable to infect the cells usually targeted by the wild-type virus, a feature that dramatically minimizes collateral toxicity.5,6

Genetically engineered HSVs have been successfully retargeted to three receptors, IL-13α2R, uPAR, and HER2.6,7,8,9,10,11 An HSV retargeted to HER2 was able to exert an efficient antitumor activity in subcutaneous models of ovarian carcinoma.10 HER2 is a clinically relevant target for brain tumors virotherapy as it is expressed in a large (15–80%) fraction of HGGs, depending on the technology employed for receptor detection.12,13,14 In gliomas, HER2 expression increases with the degree of anaplasia and has been associated with worse prognosis.13,15,16 HER2 expression is particularly high in CD133-positive GBM cells that, consequently, have been successfully targeted by HER2-specific T cells.17 Furthermore, HER2 is not expressed in healthy adult central nervous system,18 thus strengthening its suitability and specificity as target.

The oncolytic recombinant HSV-1 R-LM113 is fully retargeted to HER2. It was generated by insertion of a single chain antibody (scFv) to HER2 in the virion envelope glycoprotein gD.9 R-LM113 infects and replicates solely in cells expressing the HER2 receptor, and is unable to enter cells expressing the HSV natural receptors HVEM and nectin1.

Here, we assessed the safety and antitumor efficacy of R-LM113 in an orthotopic model of HGG. To this end, we exploited a murine GBM model based on the overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGF-B), previously developed in our laboratory19,20,21 and basically similar to one developed by Holland and colleagues.22 Such PDGF-B-induced mGBMs exhibit a gene expression profile of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and histopathological features typical of GBM, thus resembling a GBM of the recently proposed “proneural” subclass.23 For this study, the model was engineered to express HER2 and transplanted in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, whose high susceptibility allows to better evaluate R-LM113 safety.

Results

In vivo safety of R-LM113

The recombinant HSV R-LM113 was previously shown to infect selectively cells expressing HER2.9 To show that R-LM113 is not able to infect murine cells in vivo via HSV natural receptors, and therefore unable to elicit neurotoxic effects, we performed intracranial injections in NOD/SCID mice, a mouse strain highly sensitive to HSV.24

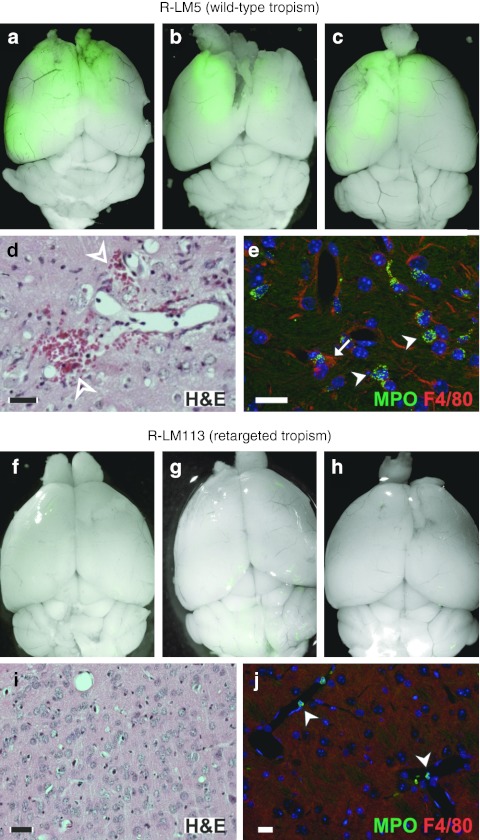

We inoculated three adult NOD/SCID mice intracranially with 3 × 105 plaque-forming unit of R-LM113. As control, the same number of animals was injected with 105 plaque-forming unit of R-LM5, a recombinant HSV exhibiting wild-type tropism and expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter. The dose for intracranial inoculation of R-LM113 was the maximum that could be administered in the small volumes allowed. All the animals inoculated with the control R-LM5 virus developed lethal encephalitis in 7–10 days following the injection. Their brain showed the presence of wide EGFP-positive areas due to virus spread (Figure 1a–c). Sections of the brains, stained with hematoxylin and eosin showed broad areas of extravasation (Figure 1d) and thickening of blood vessel walls. Staining for myeloperoxidase and F4/80 demonstrated massive infiltration of granulocytes and macrophages, respectively (Figure 1e). Mice inoculated with R-LM113 were killed on days 7, 12, and 25 postinjection, respectively, in order to evaluate any possible sign of virus spread across the encephalon. In all instances, we did not find either trace of neuroinvasiveness, as the brains were devoid of EGFP-positive areas (Figure 1f–h), or signs of extravasation or granulocytes and macrophages infiltration (Figure 1i,j). These results demonstrate that R-LM113 is safe in vivo, as it cannot infect and spread in normal brain tissue, whereas R-LM5 is invariably lethal even at a lower dose.

Figure 1.

R-LM113 is safe in vivo. Merged fluorescence and bright-field images of adult nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mouse brains after injection of (a–c) 105 plaque-forming unit (pfu) R-LM5 or (f–h) 3 × 105 pfu R-LM113. Viral spread is visualized by enhanced green fluorescent protein fluorescence. Coronal sections of adult NOD/SCID mouse brains after injection of (d,e) R-LM5 or (i,j) R-LM113, stained with (d,i) hematoxylin and eosin or (e, j) antibody for the indicated markers. To note, the presence of extravasation areas (hollow arrowheads in d) and infiltration of granulocytes (arrowheads in e) and macrophages (arrow in e) in the parenchyma of R-LM5-injected brains. On the contrary, granulocytes are exclusively found inside blood vessels of R-LM113-injected brains (arrowheads in j). Bar = 20 µm. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; MPO, myeloperoxidase.

Establishment of an in vivo HGG model expressing HER2

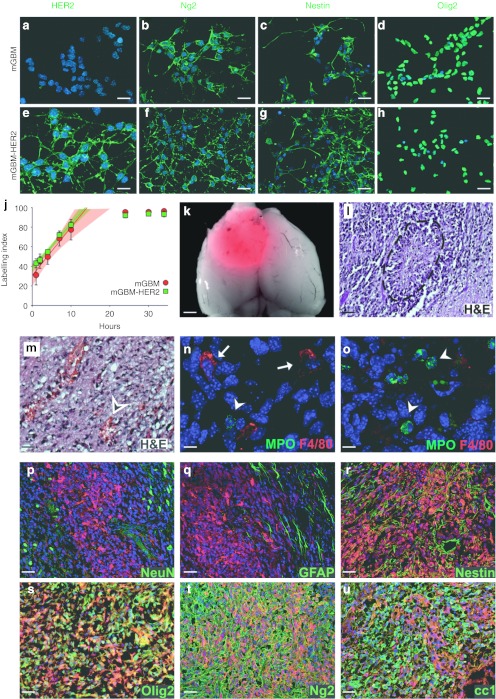

In order to obtain a murine model useful to assess the therapeutic efficacy of R-LM113, we used cells derived from PDGF-B-induced mGBM cells, which are able to generate tumors when orthotopically transplanted in adult mice and express a fluorescent reporter protein (DsRed). We stably transfected mGBM cells with a plasmid carrying the coding sequence of HER2 and confirmed the expression of the transgene by immunostaining (Figure 2a,e). Next, we ascertained whether in engineered cells (mGBM-HER2 cells) HER2 expression influenced their phenotype or impaired their tumorigenic potential. By immunocytochemical analysis, we confirmed that mGBM-HER2 cells express the same markers typical of their parental counterparts (Figure 2b–d,f–h).19,20 By a cumulative S-phase EdU labeling we also verified that the expression of HER2 does not affect cell proliferation and cell cycle length, which was indistinguishable between mGBM and mGBM-HER2 cells (Figure 2j). We then tested the tumorigenic potential of mGBM-HER2 cells by intracranial transplantation in adult NOD/SCID mice. All the transplanted animals exhibited neurological symptoms within about 2 months due to the development of large tumor masses (Figure 2k) characterized by a rather compact structure and wide necrotic areas surrounded by highly proliferating cells forming pseudopalisades (Figure 2l). Necrotic and surrounding areas showed strong signs of extravasation and inflammatory cells invasion (Figure 2m–o). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that secondary tumors derived by mGBM-HER2 cells are indistinguishable from those generated by mGBM cells in terms of expression of molecular markers such as NeuN, glial fibrillary acidic protein, Nestin, Olig2, Ng2, and CC1 (Figure 2p–u).19,20 These results demonstrated that HER2 expression does not impair tumorigenic features of mGBM cells.

Figure 2.

HER2 expression in mGBM cells does not alter their characteristics. (a–h) Immunofluorescence stainings of (a–d) mGBM and (e–h) mGBM-HER2 cultured cells for the indicated markers in green. (j) Cumulative labeling analysis using EdU was performed to compare the growth fraction, the length of the cell cycle, and the length of the S phase of mGBM (red) and mGBM-HER2 (green) cells. Cumulative labeling increases linearly depending on the length of the cell cycle and S phase, and show a plateau when all cycling cells are labeled. The regression lines for the five points preceding the plateau (up to 10 hours) and their respective confidence intervals (shadings) are represented with the same color code. Of note, the confidence interval for mGBM-HER2 lies inside that of mGBM cells, showing that their cell cycle parameters are indistinguishable. Subsequent time points (24, 30, and 34 hours) are included in the plot in order to show the plateau of the labeling indexes (also known as growth fractions). (k) Merged fluorescence and bright-field images of a typical mGBM-HER2-derived tumor in dorsal view. The tumor is detectable as DsRed expression. (l–u) Coronal sections of tumors derived by mGBM-HER2 cells stained with hematoxylin and eosin (l,m) or with the indicated antibody (n–u). The dashed line in l defines the contour of a pseudopalisade; the arrowhead in m indicates area of extravasation. Arrows indicate macrophages in n; arrowheads indicate granulocytes in n and o. DsRed endogenous fluorescence of tumor cells is visible in red in p–u. Nuclei are counterstained in blue with Hoechst 33342 in a–h, n–u. Bar = 15 µm (a and e); 25 µm (b–d, f–h, m); 1.2 mm (k); 40 µm (l, p–u); 8 µm (n and o). GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; mGBM, murine glioblastoma; MPO, myeloperoxidase.

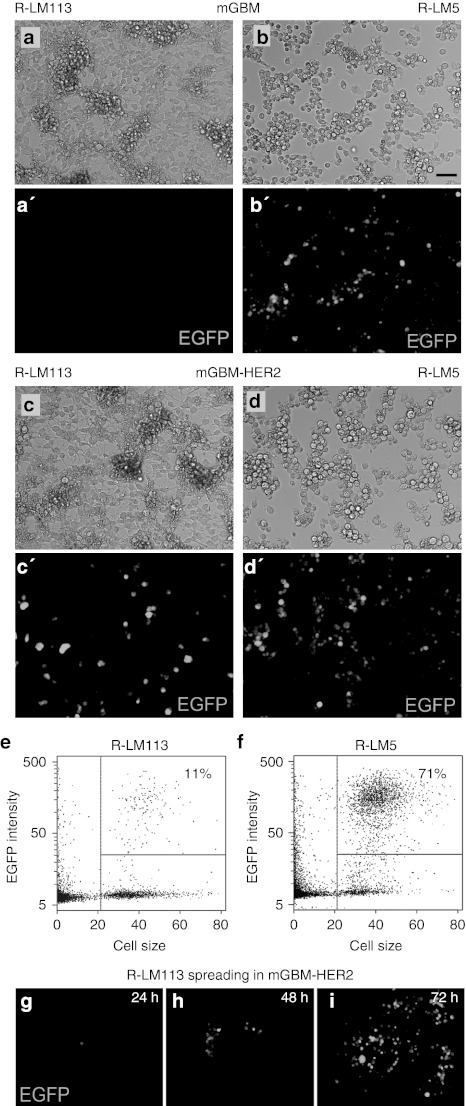

To verify that mGBM-HER2 cells are susceptible and permissive to R-LM113 infection, replicate cultures of mGBM-HER2 and mGBM cells were exposed to serial dilutions of R-LM113 or R-LM5 as control. After 24 hours, infection was detected as expression of the reporter gene EGFP (Figure 3a–d').

Figure 3.

The recombinant virus R-LM113 is able to infect solely mGBM-HER2 cells. (a–d′) Matched micrographs showing (a–d) bright-field and (a′–d′) virus-encoded EGFP fluorescence of (a,b) mGBM or (c,d) mGBM-HER2 cells 24 hours after exposure to (a,c) R-LM113 or (b,d) R-LM5 at multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 5. (e–f) Representative dot plots of mGBM-HER2 cells exposed to (e) R-LM113 or (f) R-LM5. Numbers in quadrants indicate the percentage of infected cells evaluated as EGFP expression. Lines correspond to the thresholds used. (g–i) Cell-to-cell spread of the R-LM113 recombinant virus in mGBM-HER2 at different time points after infection with MOI = 0.025. Bar = 50 µm. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

To quantify the infection efficiency of R-LM113 in mGBM-HER2 cells compared with that of the wild-type tropism HSV R-LM5, mGBM-HER2 cells were infected at the same multiplicity of infection of either virus (i.e., 0.5 plaque-forming unit/cell, as determined from titration in SK-OV-3 cells). In these experiments, R-LM113 infected about 11 ± 3% of mGBM-HER2 cells (Figure 3e) while R-LM5 infected about 71 ± 3% of cells (Figure 3f). Using the Poisson distribution, from these percentages of infection we calculated the mean number of infection events per cell which is 0.12 ± 0.03 for R-LM113 and 1.2 ± 0.08 for R-LM5. Thus, the infection efficiency of R-LM113 in mGBM-HER2 cells is about one order of magnitude lower than that of R-LM5.

R-LM113 was able to spread in the culture, as observed by monitoring over time the formation of plaques starting from mGBM-HER2 cells infected at low multiplicity of infection (0.025; Figure 3g–i). It has been previously demonstrated that cell-to-cell spread of R-LM113 is HER2-dependent, as it is inhibited by Herceptin.9

Oncolytic effect of R-LM113 on mGBM-HER2 tumors

In order to assess the ability of the R-LM113 virus to exert antitumor activity, we planned two different experimental schemes: an early treatment where virus was in contact with the tumor cells at the time of intracranial transplantation, and a late treatment in which the virus was injected into already established tumors.

For the early-treatment scheme, we intracranially transplanted, in three independent sessions, a pool of 24 adult NOD/SCID mice with about 2 × 104 mGBM-HER2 cells. Twelve mice (herein referred to as “R-LM113 early-treatment set”) received, in addition and at the same time, 2 × 104 mGBM-HER2 cells previously infected in vitro with R-LM113. The remaining 12 mice were used as control and herein referred to as “early-treatment control set.” Mice were then monitored for 160 days.

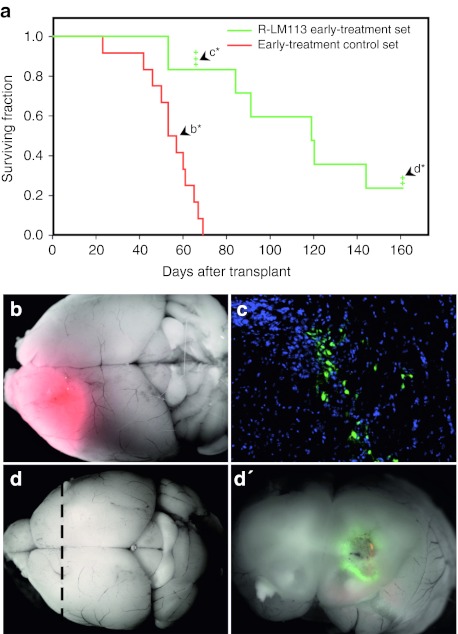

Mice belonging to the R-LM113 early-treatment set displayed a dramatically improved survival time as compared with that of the early-treatment control set, with a median survival time of 119 days versus 55 days, respectively (log-rank test P < 10−4; Figure 4a). All the animals of the control set exhibited neurological symptoms within 69 days and showed the presence of DsRed-positive tumor masses (Figure 4b). By contrast, only two animals of the R-LM113 early-treatment set developed neurological symptoms due to DsRed-positive tumor masses in the same timeframe. In order to monitor R-LM113 virus behavior, three mice randomly selected from the R-LM113 early-treatment set were killed 66 days after transplant in the absence of any neurological symptom. Macroscopic examination of the three explanted brains did not show any detectable tumor mass. After sectioning, the histological analysis showed small highly cellularized areas characterized by the presence of scattered EGFP-positive cells, indicating an ongoing infection of R-LM113 (Figure 4c). The analysis of the animals displaying neurological symptoms from 69 and 160 days after transplantation (n = 5) showed the presence of large DsRed tumor masses, 2 of which were scattered with EGFP-positive areas (Supplementary Figure S1a).

Figure 4.

R-LM113 counteracts the growth of HER2-expressing gliomas. (a) Kaplan–Meier plot for animals transplanted with mGBM-HER2 cells alone (red line: early-treatment control set) or together with R-LM113-infected mGBM-HER2 (green line: R-LM113 early-treatment set). The crosses indicate mice censored for subsequent analysis. (b) Merged DsRed fluorescence and bright-field image of a brain from a mouse of the control set (arrowhead labeled as b* in a). (c) Coronal section of the brain from a mouse of the R-LM113 early-treatment set censored 66 days post-transplant (arrowhead labeled as c* in a); in green is shown enhanced green fluorescent protein expressed from the virus, in blue the nuclei. (d) Merged red and green fluorescence and bright-field images of the brain from a mouse of the R-LM113 early-treatment set censored 161 days post-transplant (arrowhead labeled as d* in a). (d′) Coronal section of the brain shown in d, along the dashed line. mGBM, murine glioblastoma.

Two animals belonging to the R-LM113 early-treatment set survived until the end of the planned observation period and were killed in absence of any neurological symptom. One of them bore a DsRed-positive tumor mass lacking any detectable EGFP fluorescence (Supplementary Figure S1b), which was still expressing HER2 (Supplementary Figure S1c). Therefore, the treatment with R-LM113 does not select for HER2-negative tumor cells. The other animal, at the first glance, appeared tumor-free (Figure 4d). After dissection, it was found to harbor a very small region of DsRed- and EGFP-positive cells suggesting that the ongoing infection of R-LM113 was successfully counteracting tumor growth (Figure 4d').

Altogether, these data demonstrate that R-LM113 can efficiently infect, spread, and kill glioma cells in vivo, as mice injected with a mixture of uninfected and R-LM113-infected mGBM-HER2 cells display a doubling in their median survival compared with control mice.

Oncolytic effect of R-LM113 on established gliomas

The late-treatment experimental scheme, consisting of the injection of R-LM113 into already established tumors, was designed to better mimic a possible therapeutic application of the oncolytic virus. Based on the survival analysis of the early-treatment control set described above, we treated NOD/SCID mice 45 days after transplantation of 2 × 104 mGBM-HER2 cells, i.e., 10 days before the median survival of the transplanted mice. A preliminary analysis showed that, at such time point, tumor masses of variable sizes are invariably present in the brains of transplanted animals (n = 4; Supplementary Figure S2).

We injected 3 × 105 plaque-forming unit of R-LM113 intracranially in 20 mice (herein referred to as “R-LM113 late-treatment set”) in the same stereotaxic coordinates where the mGBM-HER2 had been transplanted. In parallel, as control, eight mice were injected with the same volume of ultraviolet-inactivated viral preparation (herein referred to as “UV-R-LM113 late-treatment control set”). We took into account only the animals surviving at least 5 days after virus injection, a time likely sufficient for spread of the virus, and to exclude mice which did not recover from the intracranial stereotaxic injection.

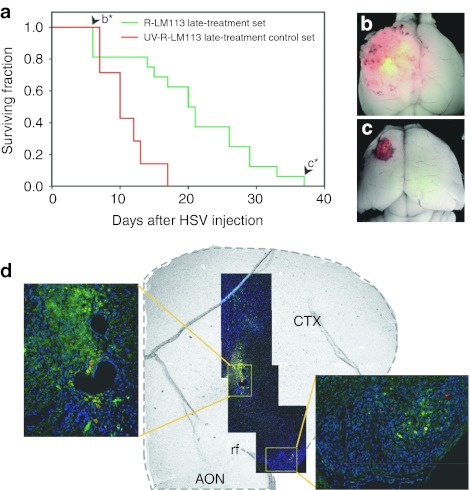

Mice belonging to the R-LM113 late-treatment set showed a statistically significant lengthening of the median survival from the treatment (21 days) compared with that of the UV-R-LM113 late-treatment control set (10 days, P < 0.003; Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

R-LM113 improves mouse survival when injected in already established HER2-expressing gliomas. (a) Kaplan–Meier plot for animals bearing mGBM-HER2 tumors inoculated with R-LM113 (green line) or with ultraviolet-inactivated R-LM113 (red line). (b,c) Merged red and green fluorescence and bright-field images of brains from mice of the R-LM113 late-treatment set died at 6 days (b, arrowhead labeled as b* in panel a) and at 37 days (c, arrowhead labeled as c* in panel a) following R-LM113 inoculation. (d) Coronal section of a mGBM-HER2-bearing mouse injected with R-LM113 and killed 5 days postinoculation. In green is shown the virally expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein, in red the endogenous fluorescence of DsRed expressed by mGBM-HER2, in blue the nuclei. The right inset shows a magnification of the region distant ~1.3 mm. AON accessory olfactory nucleus, CTX, cortex; HSV, herpes simplex virus; rf, rhinal fissure.

The first three mice from the R-LM113 late-treatment set that developed neurological symptoms displayed a large DsRed-positive tumor mass mottled by EGFP-positive areas, demonstrating that the virus was spreading into the tumor (Figure 5b). Likely these gliomas were already too advanced for effective treatment with the virus.

The mouse that survived longer in the R-LM113 late-treatment set died 37 days after the treatment, and displayed a relatively small DsRed-positive mass scattered by EGFP-positive cells (Figure 5c).

To monitor viral spread after the injection in the tumor mass, four additional mice were treated as described above, but killed 5 days following virus injection in absence of any neurological symptom. As expected, we found DsRed-positive tumors of variable size in all the brains. Within the tumor masses, we detected the presence of EGFP-positive cells which, importantly, had also reached regions far from the inoculation site, demonstrating the ability of the virus to spread into the tumor (Figure 5d).

Discussion

Attenuated HSV recombinants have already undergone successfully pilot or phase I–II clinical trials, especially against GBM.25,26,27 However, the strategies applied to attenuate HSV have some drawbacks, mainly reduced replication and nonstringent specificity of entry into cancer cells.3,4,28 The approach we undertook to preserve a replication capacity similar to that of a wild-type virus, and to confer a tumor specificity, has been to redirect viral tropism of an otherwise wild-type virus, through modification of viral envelope gD glycoprotein. We report that R-LM113 effectively counteracts tumor growth in an animal model of GBM.

We administered the virus in two different experimental settings: at the earliest possible (namely at the same time of glioma transplantation) and at almost the latest possible, i.e., 10 days before the median survival time of mice transplanted with the experimental glioma. The latter time point was chosen taking into account the rate of wild-type virus spread in the brain of NOD/SCID mice. We assumed that, if the control R-LM5 recombinant HSV with wild-type tropism needs about 10 days to spread in the encephalon, the same time could be a fair estimation for the time needed by R-LM113 to spread in the tumor mass and to exert antitumor effect. The treatments with R-LM113 improved the survival of mice, both in the early and in the late administration, with a more dramatic effect in the early administration. These results likely represent two extremes in the treatment efficacy and demonstrate that R-LM113 is capable to inhibit HER2-positive tumor growth in vivo, while remaining aneurovirulent, because mice did not display any sign of encephalitis. Importantly, the analysis of the brains, shortly after virus administration in the established tumor (late treatment), showed R-LM113 ability to spread far away from the injection site, even in regions where the HER2-positive tumor cells are scattered (Figure 5d). This feature is crucial for a therapy aimed to fight a highly invasive tumor such as GBM whose most threatening aspect is the ability of residual cells to infiltrate the brain after surgical resection. In this context, the use of retargeted HSV-1 may be critical in order to delay or to reduce the frequency of recurrences sparing the healthy tissue, as cell-to-cell spread of R-LM113 requires HER2.9 To our knowledge, this is the first report on the efficacy of a fully retargeted, nonattenuated replication-competent HSV against an intracranial model of GBM.

A potential pitfall of retargeted HSVs, which rely for entry on the interaction between chimeric forms of gD and the targeted receptor, is that the chimeric gD may not be as efficient as wild-type gD in adopting the proper folding and in triggering fusion, or may accumulate at lower amounts than wild-type gD. Although these properties of gD may explain why the infection efficiency of R-LM113 in mGBM-HER2 cells is about one order of magnitude lower compared with that of the wild-type virus, this reduction is not as high as that observed with deleted attenuated HSVs, which usually replicate to yields several order of magnitude lower than those of wild-type virus, despite the fact they efficiently enter cells through wild-type gD.

The receptor-retargeting approach has been already tested in vivo with oncolytic viruses derived from other viruses, namely measles29,30,31 and VSV viruses,32 which have been targeted to a variety of receptors (CEA, CD20, CD38, PSMA, EGFR, EGFRvIII, and HER2), and have been tested with promising results in subcutaneous and intraperitoneal tumor models, doubling the survival of the treated animals. Measles virus targeting EGFR or EGFRvIII have been employed on orthotopic xenografts of glioma in immunodeficient mice, with a significant increase of survival time,33,34 corroborating the view that retargeting is a promising strategy.

Two distinctive advantages of HSV are the availability of a specific drug to control unwanted dissemination of virus, and the large genome size, which makes it possible to insert heterologous genes, particularly immunomodulatory genes encoding cytokines such as granulocyte macrophage colony–stimulating factor and interleukin-12. This strategy, which has been defined as “arming,” is indeed very promising.35,36,37,38 Further to this, a number of point mutations, especially in gB, are known to increase the rate of entry and may balance the somewhat lower fitness of chimeric forms of gD.39 These mutations might be inserted in HER2 retargeted HSVs, carrying a cytokine, to obtain further improvements.

A second potential pitfall of retargeted viruses is the heterogeneity in the expression of the receptor of choice in the targeted tumor. Under this respect, HER2 appears to be a good target for virotherapy against brain tumors because it is absent in normal adult central nervous system, it is overexpressed by a relevant proportion of GBMs and, within this tumor, it is expressed by the tumor initiating cells.12,13,17 Importantly, GBMs express a variety of cancer specific receptors (e.g., EGFRvIII, IL-4R, IL-13α2R, uPaR) that can potentially be targeted by retargeted HSVs. Thus, it might be possible to combine different HSVs with different tropism to broaden the spectrum of targeted cells. Moreover, as HER2 is expressed by several cancers as breast and ovarian carcinoma, anti-HER2 retargeted HSVs could be employed in combination with standard therapeutic approaches or after failure of other treatments, for example after the onset of trastuzumab resistance following alterations of HER2 signaling activity.40,41

In conclusion, our results provide the first proof-of-principle that a fully retargeted HSV can increase animal survival following intracranial treatment of a glioma model that mimics the infiltrative behavior of GBM. In perspective, the generation of recombinants directed to other relevant GBM-specific receptors (e.g., EGFRvIII, IL-4R, IL-13α2R, uPaR, etc.) and the treatment of tumors with cocktails of retargeted HSVs could increase the spectrum of tumor cells reached and destroyed by the targeted therapy.

Materials and Methods

Animal procedures. Mice were handled in agreement with guidelines conforming to current Italian regulations for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (D.lvo 27/01/1992, no. 116). Procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of the National Institute of Cancer Research and by the Italian Ministry of Health. The experiments were performed on the NOD/SCID mouse strain. Anesthetized animals were injected by means of a stereotaxic apparatus. Up to 5 µl of suspension, containing 2 × 104 to 5 × 104 cells or viral preparations, were injected using a Hamilton syringe (Bregma coordinates: anterio posterior, 1.0 mm; lateral, 1.5 mm left and 2.5 mm below the skull surface). Animals were then monitored daily and, at first signs of neurologic symptoms, were killed. Their brains were photographed on a Leica fluorescence stereo microscope (Wetzlar, Germany).

Survival curves were determined using Kaplan–Meier analysis and survival between groups was compared by log-rank test.

Cell cultures and transfection. PDGF-B-induced brain tumors expressing DsRed fluorescent reporter were obtained as described previously.19,20 Tumor cell cultures derived from PDGFB/DsRed-induced gliomas (mGBM cells) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-F12 added with B27 supplement, human basic fibroblast growth factor and epidermal growth factor (10 ng/ml) and plated on Matrigel (1:200; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). mGBM cells were transfected with the pcDNA3-HER2 plasmid42 by using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), selected with neomycin G418 (Invitrogen). For growth curves, cells were fixed at different time points (1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 24, 30, and 34 hours) after EdU (Invitrogen) addition, and stained following manufacturer's instructions. Cells were photographed and analyzed with a epifluorescence microscope Axio Imager.M2 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) to evaluate the labeling index (i.e., the percentage of labeled cells) at each time points. Regression lines with the respective interval of confidence for the points preceding the plateau were computed by the method of least square. The slope and the intercept of the regression line are related to the length of the S phase and the length of cell cycle, the growth fraction corresponds to the level of the plateau, for details see ref. 43.

Immunostainings. For histological analysis, brains were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, cryoprotected in 20% sucrose and sectioned with a Leica CM3050 S cryostat or paraffin-embedded and sectioned with a Leica RM2135 Microtome. Immunostainings on brain sections or cultured cells were performed using the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal antibodies against HER2 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), nestin (1:100; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA); glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:100; Sigma, St Louis, MO), adenomatous polyposis coli (1:100, CC1; Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Olig2 (1:500; Sigma), Ng2 (1:200; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), human myeloperoxidase (1:300; DakoCytomation, Carpenteria, CA), rat antibody against F4/80 (1:30; Serotec, Oxford, UK). Binding of primary antibodies was revealed with appropriate secondary anti-rabbit IgG Dylight 488-conjugated (1:500; Jackson Immunoresearch), cy2-conjugate anti-mouse IgG (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch), cy3-conjugate anti-rat IgG (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch). Nuclei were stained through 5-min incubation in Hoechst 33342 solution (1 µg/ml; Sigma).

Cell infection. The construction and production of the recombinant virus R-LM113, retargeted to HER2, and R-LM5, with wild-type tropism, have been described elsewhere.9

Cells were infected with R-LM5 or R-LM113, at the indicated multiplicity of infection estimated on the bases of the titration in SK-OV-3 cells. The efficiency of the infection was monitored by means of EGFP expression driven by both R-LM5 and R-LM113. The percentage of infected cells was evaluated by loading them on a hemocytometer and photographed with a motorized epifluorescence microscope Axio Imager.M2 (Zeiss). Images were automatically analyzed with a ImageJ (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2007) plug-in that allows to measure and plot area and fluorescence intensity of each cell. The mean number of infection events (µie) was calculated basing on the Poisson distribution, with the formula µie = −loge(1 − q), where q is the proportion of infected cells.

For mock treatment, R-LM113 has been inactivated by exposure to ultraviolet-C light source (G 30-W Sylvania) emitting radiation of 253.7 nm for 20 minutes.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. R-LM113 counteracts the growth of HER2-expressing gliomas. Figure S2. NOD/SCID mouse brains invariably contain tumor masses at the time of HSV late-treatment.

Acknowledgments

G.C.-F. and L.M. serve as Consultants of Catherex Inc., and are co-inventors on a patent filed by the University of Bologna covering herpes simplex virus with modified tropism, uses and process of preparation thereof. Catherex did not play a role in the design and conduct of this study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the article. This work was done in Bologna and Genoa, Italy.

This work was supported by GR-2008-1135643 grant from the Italian Ministry of Health to P.M. and L.M.; by NUSUG GRANT to P.M. and IG GRANT to G.C.F. from AIRC (Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro), Milan; Fondi Roberto and Cornelia Pallotti from Department of Experimental Pathology, University of Bologna; PRIN projects from Italian Ministry for University and Research; University of Bologna RFO (Ricerca Fondamentale Orientata); Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e Ravenna to G.C.-F.; and Fondazione S. Paolo to P.M. (Molecular and cellular basis of glioma). The fellowship of E.R. was supported by Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro.

Supplementary Material

R-LM113 counteracts the growth of HER2-expressing gliomas.

NOD/SCID mouse brains invariably contain tumor masses at the time of HSV late-treatment.

REFERENCES

- CBTRUS ed.). (2011CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States, 2004–2007 Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States: Hinsdale, IL [Google Scholar]

- Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campadelli-Fiume G, De Giovanni C, Gatta V, Nanni P, Lollini PL., and, Menotti L. Rethinking herpes simplex virus: the way to oncolytic agents. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:213–226. doi: 10.1002/rmv.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti L, Campadelli-Fiume G, Nanni P, Lollini PL., and, De Giovanni C.2011The molecular basis of herpesviruses as oncolytic agents Curr Pharm Biotechnolepub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo R, Miest T, Shashkova EV., and, Barry MA. Reprogrammed viruses as cancer therapeutics: targeted, armed and shielded. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:529–540. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., and, Roizman B. Construction and properties of a herpes simplex virus 1 designed to enter cells solely via the IL-13α2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5508–5513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601258103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Ye GJ, Debinski W., and, Roizman B. Engineered herpes simplex virus 1 is dependent on IL13Rα 2 receptor for cell entry and independent of glycoprotein D receptor interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15124–15129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232588699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama H, Zhou G., and, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 recombinant virions exhibiting the amino terminal fragment of urokinase-type plasminogen activator can enter cells via the cognate receptor. Gene Ther. 2006;13:621–629. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti L, Cerretani A, Hengel H., and, Campadelli-Fiume G. Construction of a fully retargeted herpes simplex virus 1 recombinant capable of entering cells solely via human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. J Virol. 2008;82:10153–10161. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01133-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti L, Nicoletti G, Gatta V, Croci S, Landuzzi L, De Giovanni C.et al. (2009Inhibition of human tumor growth in mice by an oncolytic herpes simplex virus designed to target solely HER-2-positive cells Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1069039–9044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti L, Cerretani A., and, Campadelli-Fiume G. A herpes simplex virus recombinant that exhibits a single-chain antibody to HER2/neu enters cells through the mammary tumor receptor, independently of the gD receptors. J Virol. 2006;80:5531–5539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02725-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhem-Tonnelle V, Bièche I, Vacher S, Loyens A, Maurage CA, Collier F.et al. (2010Differential distribution of erbB receptors in human glioblastoma multiforme: expression of erbB3 in CD133-positive putative cancer stem cells J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69606–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineo JF, Bordron A, Baroncini M, Maurage CA, Ramirez C, Siminski RM.et al. (2007Low HER2-expressing glioblastomas are more often secondary to anaplastic transformation of low-grade glioma J Neurooncol 85281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabika S, Kiya K, Satoh H, Mizoue T, Kondo H, Katagiri M.et al. (2010Prognostic significance of expression patterns of EGFR family, p21 and p27 in high-grade astrocytoma Hiroshima J Med Sci 5965–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesiger EM, Hayes RL, Pierz DM., and, Budzilovich GN. Prognostic relevance of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) and c-neu/erbB2 expression in glioblastomas (GBMs) J Neurooncol. 1993;16:93–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01324695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati S, Ytterhus B, Granli US, Gulati M, Lydersen S., and, Torp SH. Overexpression of c-erbB2 is a negative prognostic factor in anaplastic astrocytomas. Diagn Pathol. 2010;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N, Salsman VS, Kew Y, Shaffer D, Powell S, Zhang YJ.et al. (2010HER2-specific T cells target primary glioblastoma stem cells and induce regression of autologous experimental tumors Clin Cancer Res 16474–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press MF, Cordon-Cardo C., and, Slamon DJ. Expression of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in normal human adult and fetal tissues. Oncogene. 1990;5:953–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appolloni I, Calzolari F, Tutucci E, Caviglia S, Terrile M, Corte G.et al. (2009PDGF-B induces a homogeneous class of oligodendrogliomas from embryonic neural progenitors Int J Cancer 1242251–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzolari F, Appolloni I, Tutucci E, Caviglia S, Terrile M, Corte G.et al. (2008Tumor progression and oncogene addiction in a PDGF-B-induced model of gliomagenesis Neoplasia 101373–82, following 1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrile M, Appolloni I, Calzolari F, Perris R, Tutucci E., and, Malatesta P. PDGF-B-driven gliomagenesis can occur in the absence of the proteoglycan NG2. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:550. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Celestino JC, Okada Y, Louis DN, Fuller GN., and, Holland EC. PDGF autocrine stimulation dedifferentiates cultured astrocytes and induces oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas from neural progenitors and astrocytes in vivo. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1913–1925. doi: 10.1101/gad.903001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valyi-Nagy T, Fareed MU, O'Keefe JS, Gesser RM, MacLean AR, Brown SM.et al. (1994The herpes simplex virus type 1 strain 17+ γ 34.5 deletion mutant 1716 is avirulent in SCID mice J Gen Virol 75 (Pt 8)2059–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow S, Papanastassiou V, Harland J, Mabbs R, Petty R, Fraser M.et al. (2004HSV1716 injection into the brain adjacent to tumour following surgical resection of high-grade glioma: safety data and long-term survival Gene Ther 111648–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert JM, Liechty PG, Wang W, Gaston S, Braz E, Karrasch M.et al. (2009Phase Ib trial of mutant herpes simplex virus G207 inoculated pre-and post-tumor resection for recurrent GBM Mol Ther 17199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert JM, Gillespie GY, Weichselbaum RR, Roizman B., and, Whitley RJ. Genetically engineered HSV in the treatment of glioma: a review. Rev Med Virol. 2000;10:17–30. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(200001/02)10:1<17::aid-rmv258>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KD, Shao MY, Posner MC., and, Weichselbaum RR. Tumor genotype determines susceptibility to oncolytic herpes simplex virus mutants: strategies for clinical application. Future Oncol. 2007;3:545–556. doi: 10.2217/14796694.3.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Hasegawa K, Russell SJ, Sadelain M., and, Peng KW. Prostate-specific membrane antigen retargeted measles virotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2009;69:1128–1141. doi: 10.1002/pros.20962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Peng KW, Harvey M, Greiner S, Lorimer IA, James CD.et al. (2005Rescue and propagation of fully retargeted oncolytic measles viruses Nat Biotechnol 23209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miest TS, Yaiw KC, Frenzke M, Lampe J, Hudacek AW, Springfeld C.et al. (2011Envelope-chimeric entry-targeted measles virus escapes neutralization and achieves oncolysis Mol Ther 191813–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Whitaker-Dowling P, Griffin JA, Barmada MA., and, Bergman I. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus targeted to Her2/neu combined with anti-CTLA4 antibody eliminates implanted mammary tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:44–52. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevakou G, Allen C, Nakamura T, Zollman P, James CD, Peng KW.et al. (2007Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-retargeted measles virus strains effectively target EGFR- or EGFRvIII expressing gliomas Mol Ther 15677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen C, Vongpunsawad S, Nakamura T, James CD, Schroeder M, Cattaneo R.et al. (2006Retargeted oncolytic measles strains entering via the EGFRvIII receptor maintain significant antitumor activity against gliomas with increased tumor specificity Cancer Res 6611840–11850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossow S, Grossardt C, Temme A, Leber MF, Sawall S, Rieber EP.et al. (2011Armed and targeted measles virus for chemovirotherapy of pancreatic cancer Cancer Gene Ther 18598–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese S, Rabkin SD, Nielsen PG, Wang W., and, Martuza RL. Systemic oncolytic herpes virus therapy of poorly immunogenic prostate cancer metastatic to lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2919–2927. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JN, Gillespie GY, Love CE, Randall S, Whitley RJ., and, Markert JM. Engineered herpes simplex virus expressing IL-12 in the treatment of experimental murine brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2208–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040557897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Coffin RS, Davis CJ, Graham NJ, Groves N, Guest PJ.et al. (2006A phase I study of OncoVEXGM-CSF, a second-generation oncolytic herpes simplex virus expressing granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor Clin Cancer Res 126737–6747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida H, Chan J, Goins WF, Grandi P, Kumagai I, Cohen JB.et al. (2010A double mutation in glycoprotein gB compensates for ineffective gD-dependent initiation of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection J Virol 8412200–12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melisko ME, Glantz M., and, Rugo HS. New challenges and opportunities in the management of brain metastases in patients with ErbB2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2009;6:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R, Yu D, Hung MC, Hortobagyi GN., and, Esteva FJ. Mechanisms of disease: understanding resistance to HER2-targeted therapy in human breast cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:269–280. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalini P, Botta L., and, Menard S. Role of p53 in HER2-induced proliferation or apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12449–12453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS., and, Caviness VS., Jr Cell cycle parameters and patterns of nuclear movement in the neocortical proliferative zone of the fetal mouse. J Neurosci. 1993;13:820–833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00820.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

R-LM113 counteracts the growth of HER2-expressing gliomas.

NOD/SCID mouse brains invariably contain tumor masses at the time of HSV late-treatment.