Background: Stromelysins MMP-3 and MMP-10 serve distinct functions, and differential inhibition by TIMPs offers one mechanism of control.

Results: MMP-10 shows reduced sensitivity to TIMP-1 and -2; the MMP-10·TIMP-1 structure provides insights into inhibitor specificity.

Conclusion: MMP sequence homology poorly predicts TIMP affinity, where subtle conformational differences shape selectivity.

Significance: Our results clarify biological protease regulation and suggest strategies for engineering TIMP selectivity.

Keywords: Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP), Protease Inhibitor, Protein Structure, Protein-Protein Interactions, Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloprotease (TIMPs), Stromelysin, Peptidase, Binding Specificity

Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinase 10 (MMP-10, stromelysin-2) is a secreted metalloproteinase with functions in skeletal development, wound healing, and vascular remodeling; its overexpression is also implicated in lung tumorigenesis and tumor progression. To understand the regulation of MMP-10 by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), we have assessed equilibrium inhibition constants (Ki) of putative physiological inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 for the active catalytic domain of human MMP-10 (MMP-10cd) using multiple kinetic approaches. We find that TIMP-1 inhibits the MMP-10cd with a Ki of 1.1 × 10−9 m; this interaction is 10-fold weaker than the inhibition of the similar MMP-3 (stromelysin-1) catalytic domain (MMP-3cd) by TIMP-1. TIMP-2 inhibits the MMP-10cd with a Ki of 5.8 × 10−9 m, which is again 10-fold weaker than the inhibition of MMP-3cd by this inhibitor (Ki = 5.5 × 10−10 m). We solved the x-ray crystal structure of TIMP-1 bound to the MMP-10cd at 1.9 Å resolution; the structure was solved by molecular replacement and refined with an R-factor of 0.215 (Rfree = 0.266). Comparing our structure of MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 with the previously solved structure of MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 (Protein Data Bank entry 1UEA), we see substantial differences at the binding interface that provide insight into the differential binding of stromelysin family members to TIMP-1. This structural information may ultimately assist in the design of more selective TIMP-based inhibitors tailored for specificity toward individual members of the stromelysin family, with potential therapeutic applications.

Introduction

The zinc endopeptidases of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)3 family are named for their role in degradation and remodeling of extracellular matrix components; they have important roles in tissue patterning during development and in wound repair and tissue maintenance postnatally (1, 2). MMP proteolytic activity is regulated by a family of physiological protein inhibitors, the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). The four TIMPs possess relatively broad and overlapping inhibitory specificity because each is capable of inhibiting most of the 23 human MMPs (3, 4).

MMP-3 (stromelysin-1) and MMP-10 (stromelysin-2) degrade a variety of extracellular matrix proteins, including collagen types III–V and fibronectin (5), and also activate other proteases, including MMP-1, MMP-7, MMP-8, and MMP-9 (6). Despite their similar substrate specificities, the stromelysins show differential patterns of transcriptional regulation and tissue distribution that hint at distinct physiological functions in processes such as skeletal development (7), wound healing (8, 9), and vascular remodeling (10, 11). MMP-3, as the archetypal member of the stromelysin subclass, has been studied more extensively, and the crystal structure of the MMP-3 catalytic domain (MMP-3cd) bound to TIMP-1 first revealed the structural basis of MMP-TIMP interaction (12). MMP-10 has been less thoroughly characterized but, with 85% amino acid identity to MMP-3 throughout the catalytic domain and with a similar range of macromolecular substrates, has been anticipated to possess similar biochemical properties. MMP-10, like MMP-3, is found to be inhibited by TIMP-1 in a stoichiometric fashion (5, 9).

Disruption of the balance between MMPs and TIMPs plays a role in the pathogenesis of diseases, including cancer, atherosclerosis, and arthritis, and MMPs have been viewed as therapeutic targets in a variety of disorders (1, 13). Although broad-spectrum MMP-inhibiting drugs have not been clinically successful in most settings (14–17), selective targeting of specific MMPs may offer more promising therapeutic strategies (15–19). Specific interest in MMP-10 as a therapeutic target has grown because it has been found to possess distinct roles in cancers, including lymphoma, lung cancer, and head and neck cancer (20–24).

To understand how differential regulation by TIMPs may contribute to the different roles of the stromelysins in physiology and disease, we have undertaken a study of the inhibition of the MMP-10 versus MMP-3 catalytic domains by physiological inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2. In finding substantial differences between these proteases with regard to inhibition by TIMPs, and in solving the crystal structure of MMP-10cd bound to TIMP-1, we provide insight into mechanisms of differential posttranslational regulation of proteolytic activity. In the long term, our findings may aid in the development of TIMP-based inhibitors with selectivity toward individual stromelysins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

TIMP Expression and Purification

The construct pTT/TIMP-1 for expression of full-length human TIMP-1 and the accompanying strain of HEK 293E cells were graciously provided by Dr. B. Toussiant (Grenoble, France) (25). For highly pure and homogenous protein without glycosylation, we have generated site-directed mutants of our expression construct with two N-linked glycosylation sites, Asn-30 and Asn-78, substituted by Ala; mutations were introduced using the QuikChange method (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA). The double mutant protein was not correctly secreted; however, we did achieve expression of TIMP-1 with either of the two individually mutated glycosylation sites.

HEK 293E cells were transfected with pTT/TIMP-1 for expression of WT TIMP-1 or with the pTT/TIMP1-N30A mutant construct using polyethyleneimine transfection reagent, and secreted WT or mutant TIMP-1 was allowed to accumulate in serum-free DMEM medium over the course of 5 days. For purification, the clarified medium was concentrated, dialyzed into buffer A (50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, and 25 mm NaCl), and purified over an SP-Sepharose column using a linear gradient of buffer B (50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, and 0.5 m NaCl). Fractions containing the WT or mutant TIMP-1 were assessed by silver-stained SDS-PAGE.

Because heterogeneous native glycosylation often interferes with the formation of crystals capable of high resolution diffraction, we performed enzymatic deglycosylation of TIMP1-N30A with peptide:N-glycosidase F (New England Biolabs) for removing the residual sugar (26), followed by gel filtration using a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) that was equilibrated and eluted with 50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, containing 150 mm NaCl. The yield of purified deglycosylated TIMP1-N30A mutant was ∼1 mg/liter, representing 20–25% recovery.

To make TIMP-2 expression construct pTT/TIMP-2, the TIMP-2 coding region from human cDNA Image clone BC052605 was amplified by PCR, adding HindIII and BglII sites at the termini, and then cloned into pTT3 using restriction enzymes HindIII and BamHI (New England Biolabs). The HindIII site was regenerated at the 5′ end of the insert, whereas BamHI/BglII sites were not. TIMP-2 was expressed following the same protocol described above for TIMP-1 and then purified on Q-Sepharose using a gradient from 0 to 0.5 m NaCl in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.5, and further purified to homogeneity using gel filtration on Superdex 75 in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.5, and 150 mm NaCl.

MMP Expression and Purification

The proMMP-3 catalytic domain (proMMP-3cd) expression construct was a generous gift of H. Nagase (27). ProMMP-3cd was expressed, refolded, and purified essentially as described previously (27). Briefly, recombinant protein was extracted from inclusion bodies in a solution containing 8 m urea, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.6, 20 mm dithiothreitol, and 50 μm ZnCl2. The protein was purified on Q-Sepharose equilibrated with 8 m urea, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.6, and 50 μm ZnCl2 and eluted using a linear gradient of NaCl to 0.5 m. Fractions containing proMMP-3cd were combined, diluted to A280 of ≤0.1, and refolded by stepwise dialysis with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mm CaCl2, and 150 mm NaCl. Subsequently, purified proMMP-3cd was activated overnight in the presence of the organomercurial compound 4-aminophenyl mercuric acetate (1 mm at 37 °C) (28–30).

The proMMP-10 catalytic domain (proMMP-10cd) from human MMP-10 cDNA Image clone NM_002425 was subcloned into pET-3a using restriction enzymes BamHI and NdeI. The proMMP-10cd was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) and accumulated as insoluble cytoplasmic inclusion bodies. Purification was performed as described above for proMMP-3cd. 4-Aminophenyl mercuric acetate activation of proMMP-10cd proceeded much more rapidly than proMMP-3cd activation as has been reported previously (31), with activation completed within 1 h; however, autocatalytic degradation of the activated MMP-10cd in the presence of 4-aminophenyl mercuric acetate was also apparent on a similar time scale and progressed rapidly with further incubation. To minimize degradation, the active MMP-10cd was quickly purified from residual proMMP-10cd and degradation products by gel filtration on Superdex 75 equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 4 mm CaCl2, and 150 mm NaCl.

MMP Activity Assays

Briefly, proteolytic activities of preincubated MMP/TIMP mixtures were measured using colorimetric thiopeptolide substrate Ac-Pro-Leu-Gly-(2-mercapto-4-methyl-pentanoyl)-Leu-Gly-OC2H5 (Enzo Life Sciences). MMP-10cd at a final concentration of 25 nm was mixed with substrate of final concentration 100 μm in 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, 10 mm CaCl2, 0.05% Brij-35, and 1 mm 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) at 37 °C (32, 33), and linear initial rates were measured as an increase in the absorbance at 410 nm (°410 = 13,600 m−1 cm−1) over a 3-min time course on an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies). The activity of MMP-3cd at a final concentration of 12.5 nm was measured similarly, except all incubations were at pH 6.0. Concentrations of purified TIMPs were determined by titration against a reference stock of MMP-3cd, and concentrations of MMP-10cd were determined by titration against a reference stock of TIMP-1 that had been titrated against MMP-3cd, essentially as described previously (34). Data were fitted using linear regression analyses and extrapolated to the stoichiometric equivalence point (35) in Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego CA).

MMP-TIMP Binding Studies

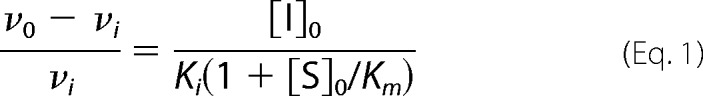

Inhibition constants (Ki) were determined using a method derived for slow, tight binding inhibitors (36, 37). Mixtures of inhibitor (WT TIMP-1 ranging from 5 to 25 nm or TIMP-2 ranging from 5 to 50 nm), substrate (100 μm for MMP-3cd and 200 μm for MMP-10cd), and assay buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 6.0, 10 mm CaCl2, 0.05% Brij-35, and 1 mm 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) were mixed at 25 °C, and then reactions were initiated by the addition of enzyme (0.5 nm for MMP-3cd and 1 nm for MMP-10cd). Reactions were followed spectroscopically for 16 h to obtain reliable steady-state rates. Data were analyzed using Equation 1 as described previously (36, 37), where νi and ν0 are steady-state rates in the presence and absence of inhibitor, and [S]0 and [I]0 are initial substrate and inhibitor concentrations. Km is the Michaelis constant for hydrolysis of the thiopeptolide substrate by the relevant MMPcd, determined in our laboratory by kinetic studies: 414 μm for MMP-3cd and 7900 μm for MMP-10cd. Concentrations of thiopeptolide substrate were determined by an end point assay.

|

The plot of (ν0 − νi)/νi versus [I]0 generates a straight line passing through the origin with a slope of 1/Ki(1 + [S]0/Km), allowing determination of Ki; Equation 1 was derived under the assumption of [I]0 ≫ [E]0. In our slow binding studies with MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd, [I]0/[E]0 ranged from 5 to 50. We felt that the use of the method described was appropriate as evidenced by the observations that (a) our data were well fitted by this model, and (b) measurement of MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 affinity by this method yielded a Ki consistent with previously reported values for this interaction (34, 38). Reported Ki values in Table 1 are averages obtained from multiple highly consistent individual experiments.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition constants (Ki) of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 against MMP-3cd and MMP-10cd

| Inhibitor | MMP-3cd | MMP-10cd |

|---|---|---|

| m | m | |

| TIMP-1 | 1.3 × 10−10 | 1.1 × 10−9 |

| TIMP-2 | 5.5 × 10−10 | 5.8 × 10−9a |

a Inhibition was not detected using the slow binding method but instead was measured in a classic competitive inhibition study as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

The method above did not yield reliable data for the weaker inhibition of MMP-10cd by TIMP-2. Instead, Ki was measured using the classic competitive inhibition model as we have described previously for weak inhibitors of serine proteases (36, 39). TIMP-2 (5–40 nm) and MMP-10cd (5 nm) were mixed in assay buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, 10 mm CaCl2, 0.05% Brij-35, and 1 mm 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) and briefly equilibrated to 37 °C, and then reactions were initiated by the addition of substrate (500–6000 μm). We verified that inhibition had reached equilibrium after this brief equilibration by testing a series of equilibration times and finding no change in measured initial rates. Reactions were followed spectroscopically for 3 min to obtain initial rates. Data were globally fitted by multiple regression to the classic competitive inhibition equation (Equation 2) using Prism 4. The Ki reported in Table 1 is an average value obtained from two highly consistent independent experiments.

|

Crystallization and Data Collection

A 1:1.2 (mol/mol) mixture of MMP-10cd and fully deglycosylated TIMP-N30A was concentrated to achieve a final protein concentration of 4–5 mg/ml. Crystals were grown at room temperature in 0.1 m sodium dihydrogen phosphate, pH 6.5, 12% (w/v) PEG 8000 (Qiagen Protein Complex suite), using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals appeared in 2 weeks and grew over the course of several weeks to an approximate size of 0.5 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm. Promising crystals were soaked in a cryoprotectant solution (0.1 m sodium dihydrogen phosphate, pH 6.5, 12% (w/v) PEG 8000, and 30% glycerol) and cryocooled in liquid N2.

Beam line X12-C was used to screen crystals at the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory. X-ray diffraction data were collected to 1.9 Å at 100 K. Crystals of the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex belong to the space group P21212, with unit cell dimensions of a = 231.72, b = 37.68, c = 39.52, and contain one molecule in the asymmetric unit with solvent content of about 40%. The data were evaluated, merged, and scaled using DENZO/SCALEPACK (40). Details of data processing statistics are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics for MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank code | 3V96 |

| Complexes per asymmetric unit | 1 |

| Space group | P21212 |

| Unit cell (Å) | 231.72, 37.68, 39.52 |

| 90°, 90°, 90° | |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.9 |

| Unique reflections | 26,280 |

| Completeness (%) | 91.81 (54.9)a |

| Multiplicity | 6.3 (2.9)a |

| Mean I/(σ) | 23.5 (1.4)a |

| Rmerge | 0.068 (0.785)a |

| Rsym | 0.068 (0.785)a |

| Rcryst/Rfree (%) | 0.215/0.266 |

| r.m.s. deviation | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.021 |

| Angles (degrees) | 1.948 |

| Protein atoms | 2578 |

| Ions | 2 (Zn2+), 3 (Ca2+), and 2 (PO42−) |

| Water molecules | 188 |

| Φ,Ψ angle distributionb | |

| In favored regions | 242 (87.7%) |

| In additionally allowed regions | 30 (10.9%) |

| In generously allowed regions | 4 (1.4%) |

a Values in parenthesis are for the highest resolution shell (1.93–1.9 Å).

b Ramachandran distribution is reported as defined by Molprobity/Protein Data Bank validation.

Structure Determination and Refinement

The x-ray structure of the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex was solved by molecular replacement using the program Phaser (41) operated by CCP4. The previously solved structures of human MMP-10cd, including two zinc and three calcium metal ions (Protein Data Bank code 1Q3A), and of TIMP-1 (Protein Data Bank code 1UEA, chain B) were used as search models. Following molecular replacement, ARP/wARP was used for automated rebuilding of the TIMP-1 domains (42, 43). The refinement was carried out using Refmac5 (44), adding water molecules into difference peaks (Fo − Fc) greater than 3σ, and manual rebuilding with COOT (45). A test set of 5% of the total reflections assigned was excluded from the refinement for Rfree monitoring. TLS refinement was applied (46), initially using one TLS value for the MMP catalytic domain and two for the TIMP-1 N- and C-terminal subdomains. Observation of poor density in multiple regions of TIMP-1 and difficulties in rebuilding these segments either using ARP/wARP or manually indicated that conformational heterogeneity in segments of TIMP-1 created a challenge to model improvement. Because of the flexibility of these segments and the possibility that they might demonstrate local trajectories of motion partially decoupled from the larger TIMP-1 subdomain units, we tested multiple TLS groupings for TIMP-1 and chose groups that empirically yielded the best R and Rfree improvement and overall improvement in map quality. Ultimately, MMP-10cd (chain B) and associated metal ions comprised one TLS group, whereas TIMP-1 (chain A) was divided and assigned to seven separate TLS groups. Phosphate ions and alternate side chain conformations were also added using COOT. MMP-10 residues Phe-242 to Glu-244 (chain B), missing from the original search model, were manually built into the electron density maps (2Fo − Fc) using COOT. The final stage of restrained refinement included water molecules with peaks greater than 1σ and within acceptable H-bonding distances from neighboring protein atoms and two phosphate ions. The final R/Rfree was 0.215/0.266. TIMP-1 residues Gly-25 to Ala-30 and Gln-50 to Asp-57 were omitted from chain A because of lack of ordered electron density.

Structural Analyses

Structure superpositions of MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 (our model) and other MMP-TIMP complexes were performed using PyMOL (Python-enhanced molecular graphics tool) to simultaneously minimize the r.m.s. deviation between aligned Cα atoms in both enzyme and inhibitor chains. Analysis of interface contacts and estimation of changes in solvation energy were performed using the PISA server (PDBePISA Protein Interfaces, Surfaces, and Assemblies (47)) for MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 (1UEA) and MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 (our model). Structure figures were created using PyMOL.

RESULTS

Specificity of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 for Inhibition of Stromelysins

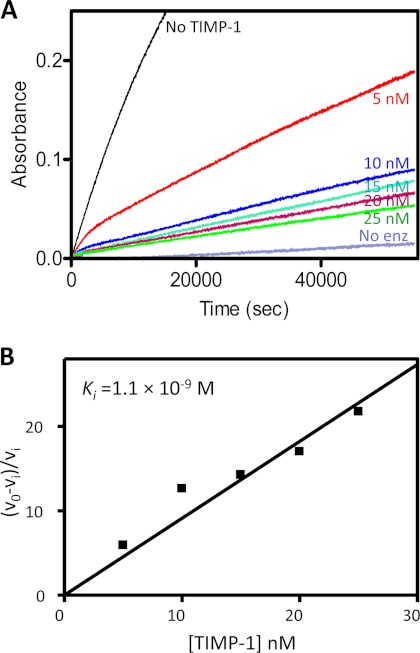

To identify likely physiological inhibitors of MMP-10, we measured equilibrium dissociation constants (Ki,) describing the interactions of MMP-10cd with TIMP-1 and TIMP-2; these inhibitors were chosen because they are widely expressed in most tissues and because qualitative studies have described previously the inhibition of MMP-10 by TIMP-1 (5) and the formation of SDS-stable complexes of MMP-10 with TIMP-1 and -2 (9). For comparison, we measured values for MMP-3cd inhibition by these inhibitors, using the same methods and similar conditions. We employed a method appropriate for slow, tight binding inhibitors that we have established in our laboratory previously (36, 39, 48–50). A series of parallel reactions using a colorimetric substrate and varying inhibitor concentrations was measured spectroscopically as the MMP-TIMP binding equilibrium was approached and steady-state rates were achieved; inhibition curves were analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The Ki value obtained by this method for inhibition of MMP-3cd by TIMP-1 (Table 1) is consistent with previous reports (34, 38). TIMP-1 inhibited the MMP-10cd with a Ki of 1.1 × 10−9 m (Fig. 1, A and B); this interaction is 10-fold weaker than that with the similar MMP-3cd (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Slow, tight binding inhibition of MMP-10cd by TIMP-1. A, a 16-h time course shows attainment of binding equilibrium by a series of parallel proteolysis reactions with varying [TIMP-1] as indicated in the figure. B, Ki for inhibition of MMP-10cd by TIMP-1 was determined from the slope of the replot as explained under “Experimental Procedures.” Data and analyses are from a representative experiment that was replicated several times with consistent results.

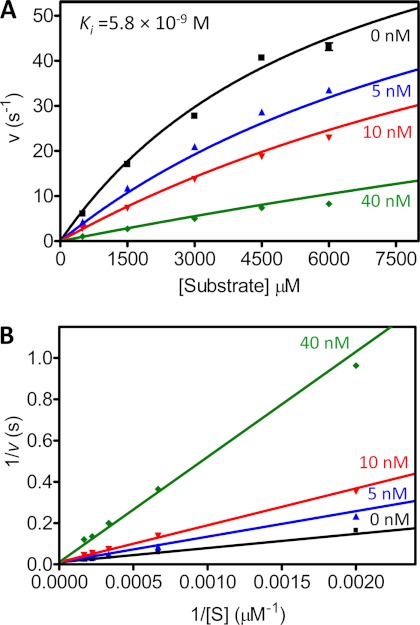

Surprisingly, although we measured potent inhibition of the MMP-3cd by TIMP-2 (Ki = 5.5 × 10−10), we were unable to reliably detect TIMP-2 inhibitory activity toward the MMP-10cd using the same slow, tight binding experimental approach. By employing instead a classic competitive inhibition experimental design appropriate for detecting weaker inhibitory interactions, we found that TIMP-2 inhibited the MMP-10cd with a Ki of 5.8 × 10−9 m (Fig. 2, A and B). In aggregate, the binding data of Table 1 highlight the observation that despite 85% sequence identity in their catalytic domains, stromelysins MMP-3 and -10 differ considerably in the strength of their interactions with TIMPs.

FIGURE 2.

Competitive inhibition of MMP-10cd by TIMP-2. A, 20 proteolysis reactions were run in duplicate, varying [substrate] from 500 to 6000 μm and [TIMP-2] from 0 to 40 nm as indicated on the figure. Data were fit globally to the competitive inhibition equation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, the Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal transform shows convergence on the y axis as is characteristic of competitive inhibition.

Crystal Structure of MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 Complex

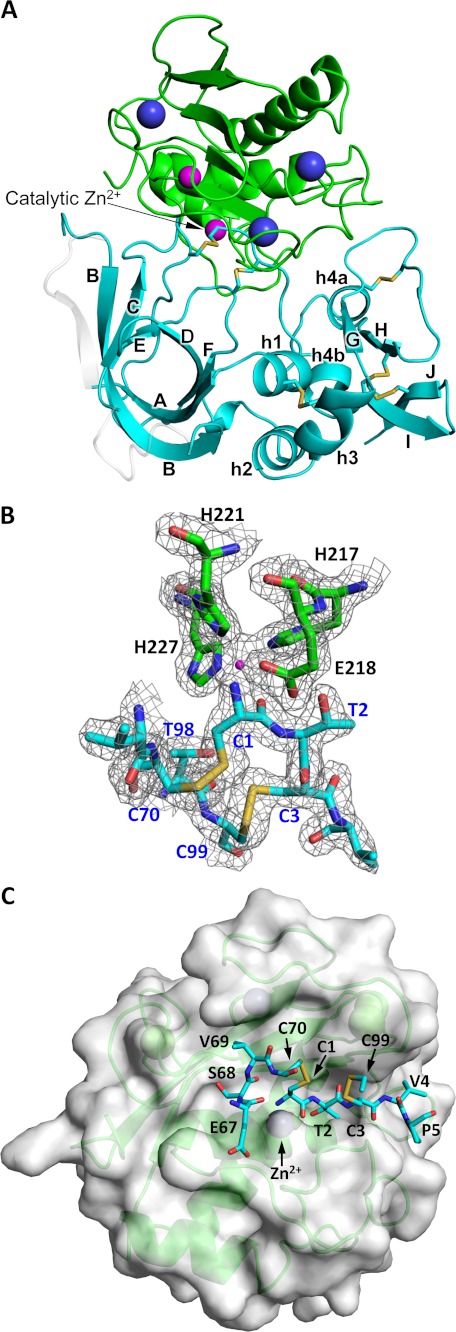

To gain insight into the differential sensitivity to TIMP-1 of members of the stromelysin family, we crystallized and solved the structure of the human MMP-10cd in complex with deglycosylated full-length TIMP-1 at 1.9 Å resolution. The structure was solved by molecular replacement, and the model was refined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Crystals of the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex belong to the space group P21212, and contain a single copy of the complex in the asymmetric unit. In our model, the TIMP-1 molecule is designated as chain A and the MMP-10cd molecule as chain B. The final refined model includes 323 protein residues, 188 water molecules, three calcium ions, two zinc ions, and two phosphate ions. Table 2 summarizes the crystallographic and refinement statistics.

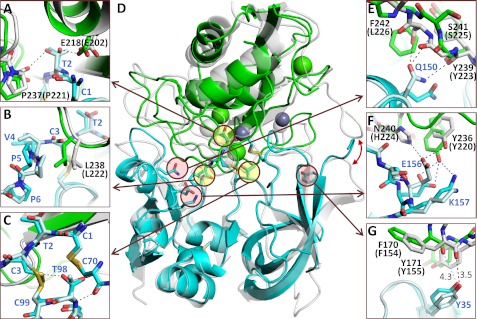

The MMP-10cd in our structure is 159 residues in length and possesses the classic metzincin fold that is characteristic of all MMPs and other metallopeptidases of this clan (Fig. 3, A and C) (51). The active site of the domain possesses the conserved zinc-binding motif HEXXHXXGXXH, in which the imidazole side chains of His-217, His-221, and His-227 coordinate the catalytic zinc ion, and Glu-218 is positioned to function as a general acid/base in the hydrolysis reaction (Fig. 3B) (52). The MMP-10cd structure is highly similar to the only other reported structure of this enzyme (Protein Data Bank code 1Q3A) (53), with r.m.s. deviation between analogous Cα atoms of 0.38 Å. The only substantial deviation from the earlier structure is found in residues 239–247, within the flexible “specificity loop” that forms the bottom of the primed side of the substrate-binding cleft and helps to shape the S1′ specificity pocket (52).

FIGURE 3.

Crystal structure of the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex. MMP-10cd is shown in green, with zinc ions in magenta and calcium ions in purple; TIMP-1 is shown in cyan. A, a structural overview of the refined model is shown, oriented in the typical view for MMP-TIMP complexes with the N-terminal subdomain of TIMP-1 on the left, composed of β-barrel strands A–F and α-helices h1–h3, and the C-terminal subdomain on the right, composed of β-strands G–J, helices h4a and h4b, and connecting loops. Residues of TIMP-1 that were disordered and not modeled in the present structure are here shown in semitransparent white with coordinates taken from the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structure 1UEA. B, the active site of TIMP-1-inhibited MMP-10cd shows MMP His and Glu side chains and the TIMP Cys-1 terminal amine liganded to the catalytic zinc. The 2Fo − Fc electron density map is shown contoured at 1.5σ. C, here MMP-10cd is shown with a semitransparent surface in the standard MMP frontal orientation, featuring a horizontally aligned active site cleft with non-primed side subsites to the left of the catalytic zinc and primed side subsites to the right. The TIMP-1 residues that bind to the active site cleft are shown in a stick representation, including N-terminal residues 1–5 that occupy the primed side subsites and CD loop residues 67–70 that fill the non-primed side subsites in a nonproductive orientation.

TIMP-1 in complex with MMP-10cd possesses a structure characteristic of TIMPs (54, 55), composed of an N-terminal subdomain with an oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide binding fold tightly packed against a C-terminal subdomain made up of two two-stranded β-sheets and several short helical segments connected by loops (Fig. 3A). The fold of the molecule is stabilized by six disulfide bonds, three within each subdomain. Comparing our TIMP-1 structure with that of the only other full-length TIMP-1 structure reported, solved in complex with the MMP-3cd by Gomis-Rüth et al. (12), we calculate r.m.s. deviation for analogous Cα atoms of 0.60 Å. The relative orientations of the N- and C-terminal subdomains in the two structures are indistinguishable, suggesting that despite the characterization of the N-terminal subdomain as an independently folding unit (54), the intact TIMP-1 molecule behaves as a single globular domain. Several regions of TIMP-1 are disordered in our structure, and we have omitted residues Gly-25 to Ala-30 and Gln-50 to Asp-57 from our model due to lack of sufficient electron density. The disordered residues are located in the AB and BC loops, 12 Å or more removed from the well defined enzyme-inhibitor interface. Regions of TIMP-1 showing substantial backbone deviations between the two structures include residues 31–33 of the AB loop, residues 63–66 and 75–78 of the CD loop, strand F, strand G, the GH loop, and residues 153–156 of the loop connecting the short helical segments (the “multiple turn” loop).

The MMP-10cd/TIMP-1 interface displays the conserved mechanism of inhibition seen in previously determined MMP-TIMP structures (12, 56–59), in which the N-terminal amine of TIMP-1 Cys-1 forms salt bridges with the MMP catalytic glutamate carboxylate oxygens and also coordinates to the catalytic zinc (Fig. 3, B and C), displacing the zinc-bound water molecule usually present at the MMP active site and thus removing the nucleophile essential for peptide bond hydrolysis. Residues Thr-2, Cys-3, and Val-4 occupy the S1′–S3′ subsites of the MMP-10cd substrate binding cleft, whereas residues 67–70 of the CD loop interact with the non-primed side of the cleft, with residues Ser-68 and Val-69 filling the S2 and S3 subsites in an orientation reversed from that of a substrate (Fig. 3C). Additional contacts with the enzyme are formed by discontinuous segments of both subdomains, including EF loop residues Thr-98 and Cys-99, residues 132–135 in the cross-bridged segment of the GH loop, and residues 150–151 and 154–157 in the multiple turn loop of the C-terminal subdomain (Fig. 3A). However, despite strong global similarities in the modes of TIMP-1 binding to MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd, we find both subtle and more pronounced differences distinguishing the interactions in these complexes.

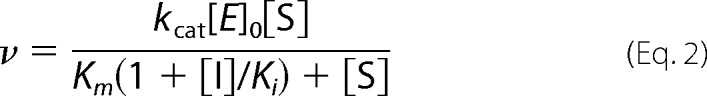

Structural Differences in TIMP-1 Interactions with MMP-10cd versus MMP-3cd

Because we found that TIMP-1 binds to stromelysin family members MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd with inhibition constants that differ substantially (Table 1), we compared the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 and MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 complexes to identify structural determinants of this functional distinction. As calculated by the protein interfaces, surfaces, and assemblies service PISA at the European Bioinformatics Institute (47), the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex buries 1173 and 1242 Å2 of solvent-accessible area on MMP-10 and TIMP-1, respectively, whereas the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 complex buries 1241 and 1354 Å2 of solvent-accessible area on MMP-3 and TIMP-1, respectively. The change in solvation energy on binding is estimated to favor complex formation by 16.8 kcal/mol for MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex and by 19.9 kcal/mol for MMP-3cd·TIMP-1.

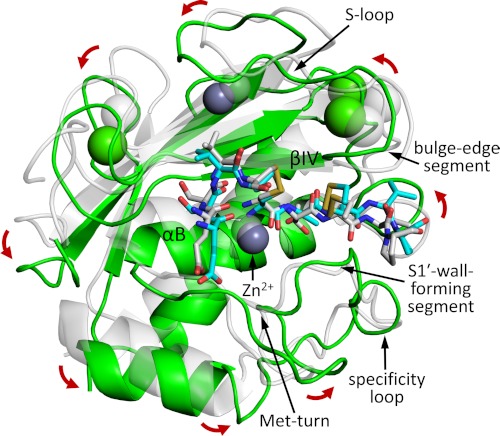

In comparing the overall positioning of the enzyme catalytic domains relative to TIMP-1, we find that the two MMPs differ by a slight rotation. When the two complexes are aligned and viewed in the standard MMP frontal orientation with horizontally aligned active site cleft (60), the MMP-10cd is rotated ∼8° counterclockwise relative to the MMP-3cd, around a z axis drawn through the catalytic zinc (Fig. 4). The impact of this rotation on the intermolecular interface is to subtly shift conformations and contacts of residues near the center of the interface and to more dramatically shift contacts and hydrogen bonding partners of residues nearer the periphery of the interface.

FIGURE 4.

Orientation of TIMP-1-bound MMP-10cd relative to MMP-3cd. MMP-10cd (green) in standard frontal orientation and TIMP-1 residues 1–5 and 67–70 (cyan) are shown superposed with the equivalent features from the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structure 1UEA (pale gray); superposition was calculated to minimize r.m.s. deviation for all Cα atoms in both the MMP and TIMP-1 molecules. Key MMP structural features that shape the substrate-binding cleft are labeled and indicated with arrows. Whereas the two TIMP-1 molecules align fairly closely, the MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd differ in orientation by a rotation of ∼8°, as indicated by the red arrows around the periphery.

In examining those contact residues at the heart of the interface, we find conformational differences at several TIMP-1 residues previously shown to be important for MMP specificity, including residues Thr-2, Val-4, and Thr-98 (Fig. 5, A–D). In MMP-10cd·TIMP-1, Thr-2 Oγ is hydrogen-bonded to MMP-10cd Glu-218 Oϵ1, whereas Thr-2 presents an alternate rotamer in the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structure, hydrogen-bonding to Pro-221 oxygen (Fig. 5A). TIMP-1 Val-4 adopts both different backbone conformations and different rotamers in the MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd complexes; this appears to be the result of a shift in MMP-10 specificity loop residue Leu-238, which propagates into significant backbone shifts in TIMP-1 residues Cys-3, Val-4, and Pro-5, and displacement of the Pro-5 ring by 2.6 Å toward the C-terminal domain of TIMP-1 (Fig. 5B). TIMP-1 Thr-98 also adopts a novel rotamer in the MMP-10cd complex, in which Thr-98 appears to be positioned with appropriate geometry to form an unusually short (3.05 Å) sulfur-containing hydrogen bond (61) between donor Thr-98 Oγ and acceptor half-cystine Sγ of Cys-3 (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Global and local differences in MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd interactions with TIMP-1. MMP-10cd (green) bound to TIMP-1 (cyan) is superposed with the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structure 1UEA (pale gray). MMP-10cd residues are labeled in black, with equivalent MMP-3cd numbering following in parentheses; TIMP-1 residues are labeled in blue. A, TIMP-1 Thr-2, which binds in the MMP S1′ specificity pocket, occupies different rotamers in the MMP-10cd-bound and MMP-3cd-bound structures, H-bonding to Glu-218(202) or Pro-237(221), respectively. B, TIMP-1 residue Val-4 is present in different rotamers, and Pro-5 is displaced by 2.6 Å between the MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd complexes. C, TIMP-1 Thr-98 adopts different rotamers in the two structures, in the MMP-10cd complex forming a short polar contact with Cys-3. D, the superposed MMP-10cd and MMP-3cd complexes with TIMP-1 are shown here from the opposite face shown in Fig. 3A, with the TIMP-1 N-terminal subdomain on the right and the C-terminal subdomain on the left. Sites of structural differences at interface residues known to be important for TIMP specificity are highlighted with yellow circles and magnified in A–C; additional differences in polar interface contacts between the complexes are highlighted with pink circles and magnified in E–G. The red double-headed arrow on the right highlights contacts between the MMP-3cd N terminus and the TIMP-1 AB loop that are absent in the MMP-10cd complex. E, TIMP-1 Gln-150 makes three H-bonds to MMP-3cd but none to MMP-10cd. F, TIMP-1 Glu-156 forms a salt bridge/H-bond and an additional H-bond with MMP-3cd, whereas a different network of H-bonds is present in the MMP-10cd complex. G, the TIMP-1 Tyr-35 side chain forms an H-bond to MMP-3cd but not to MMP-10cd.

In protein-protein binding interfaces, although a significant proportion of binding energy derives from hydrophobic contacts, the specificity of binding is strongly influenced by patterns of electrostatic interactions, where both interfacial salt bridges and hydrogen bond networks can offer significant stabilization (62–64). The number of hydrophilic bridges across the binding interface has been found to show strong positive correlation with free energy (63). Accordingly, we examined the stromelysin/TIMP-1 interfaces to identify differences in polar contacts. Enumerating the interfacial salt bridges and hydrogen bonds in the two complexes (Table 3), we observed that the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 structure has three salt bridges, one of which fulfills H-bonding criteria, and 18 additional H-bonds, including one bifurcated three-center H-bond (65, 66). In comparison, the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structure also possesses three salt bridges, two of which fulfill H-bonding criteria, and 21 additional H-bonds, three more than in the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 structure.

TABLE 3.

Electrostatic interactions at the TIMP-1/MMP-10cd or TIMP-1/MMP-3cd interface

| TIMP-1 |

MMP-10cd |

MMP-3cd |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | Atom | Residue | Atom | Distance | Typea | Residue | Atom | Distance | Typea |

| Å | Å | ||||||||

| Cys-1 | O | His-217 | NE2 | 3.14 | H | His-201 | NE2 | 3.07 | H |

| Cys-1 | O | His-227 | NE2 | 3.21 | H | His-211 | NE2 | 2.72 | H |

| Cys-1 | N | Glu-218 | OE1 | 3.19 | S | Glu-202 | OE1 | 3.39 | H,S |

| Cys-1 | N | Glu-218 | OE2 | 2.85 | H,S | Glu-202 | OE2 | 3.94 | S |

| Thr-2 | O | Leu-180 | N | 2.78 | H | Leu-164 | N | 3.04 | H |

| Thr-2 | O | Ala-165 | N | 3.49 | H | ||||

| Thr-2 | N | Ala-165 | O | 2.97 | H | ||||

| Thr-2 | N | Ala-181 | O | 3.23 | H | ||||

| Thr-2 | N | Glu-202 | OE2 | 3.32 | H | ||||

| Thr-2 | N | Glu-218 | OE1 | 3.04 | H | ||||

| Thr-2 | OG1 | Glu-218 | OE1 | 2.57 | H | ||||

| Thr-2 | OG1 | Pro-221 | O | 3.12 | H | ||||

| Cys-3 | O | Tyr-239 | N | 2.93 | H | Tyr-223 | N | 3.04 | H |

| Cys-3 | N | Pro-237 | O | 3.00 | H | Pro-221 | O | 2.96 | H |

| Val-4 | N | His-178 | O | 3.01 | H | Asn-162 | O | 2.89 | H |

| Leu-34 | O | Tyr-171 | OH | 2.66 | H | Tyr-155 | OH | 2.63 | H |

| Tyr-35 | OH | Phe-154 | O | 3.51 | H | ||||

| Ala-65 | N | Tyr-155 | OH | 3.79 | H | ||||

| Glu-67 | OE1 | His-227 | N | 2.93 | H | His-211 | N | 3.17 | H |

| Glu-67 | OE1 | His-227 | ND1 | 3.98 | S | ||||

| Ser-68 | O | Ala-183 | N | 3.21 | H | Ala-167 | N | 3.29 | H |

| Ser-68 | OG | Ala-183 | O | 2.60 | H | ||||

| Val-69 | N | Ala-183 | O | 3.88 | H | Ala-167 | O | 3.88 | H |

| Arg-75 | NH2 | His-227 | O | 3.39 | H | ||||

| Ser-134 | OG | Gly-192 | N | 3.11 | H | ||||

| Ile-135 | N | Ala-206 | O | 2.73 | H | ||||

| Gln-150 | NE2 | Tyr-223 | O | 3.19 | H | ||||

| Gln-150 | OE1 | Ser-225 | N | 3.88 | H | ||||

| Gln-150 | OE1 | Ser-225 | OG | 2.76 | H | ||||

| Gln-156 | OE1 | His-224 | NE2 | 3.07 | H,S | ||||

| Gln-156 | OE1 | Tyr-220 | OH | 3.14 | H | ||||

| Gln-156 | OE1/OE2 | Tyr-236 | OH | 3.05/3.10 | H | ||||

| Lys-157 | NZ | Tyr-236 | OH | 3.35 | H | ||||

a H and S, hydrogen bond and salt bridge, respectively.

We also looked closely at specific altered polar contacts at the MMP/TIMP interface, and highlight some of the most noticeable in the right panels of Fig. 5. TIMP-1 Gln-150, which is located on helix 4a at the top of the C-terminal subdomain at the interface with the TIMP-1 N-terminal subdomain and the enzyme specificity loop, makes three intermolecular hydrogen bonds in the MMP-3cd structure but none in the MMP-10cd structure (Fig. 5E). TIMP-1 Glu-156 and Lys-157, also located at the interface of the C-terminal subdomain with the MMP specificity loop, display altered networks of hydrogen bonds involving MMP-10 Tyr-236 (MMP-3 Tyr-220) and MMP-3 His-224; only in the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 complex is a 3.1-Å salt bridge formed between Glu and His (Fig. 5F). Finally, in the intermolecular interface region where the TIMP-1 AB loop contacts the MMP “S-loop” between β-strands III and IV, TIMP-1 Tyr-35 Oγ forms an H-bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of MMP-3cd Phe-154, whereas an equivalent H-bond is not formed in the MMP-10cd complex, where the interatomic distance stretches to 4.3 Å (Fig. 5G).

Another quite striking difference in this region of the interface is the greater extent of surface area buried in the MMP-3cd complex due to hydrophobic contacts formed between the TIMP-1 AB loop and the N-terminal residues of MMP-3 (indicated on the right side of Fig. 5D by the double-headed red arrow). By contrast, although the proteolytically activated MMP-10cd is expected to have an N-terminal sequence of equivalent length to that of MMP-3cd, beginning with Phe-Ser-Ser-Phe-Pro-Gly (6), these six amino acids are apparently unstructured in our crystal, and no contacts are observed between the AB loop of TIMP-1 and the MMP-10cd.

DISCUSSION

Here we have examined the inhibition of stromelysins by TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, finding that both TIMPs show similar selectivity in inhibiting MMP-3cd roughly an order of magnitude more strongly than MMP-10cd. We report the crystal structure of MMP-10cd in complex with TIMP-1 determined at 1.9 Å resolution, along with structural comparisons distinguishing MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 contacts from those found in the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 complex, which help to explain the observed differences in binding affinities. Relevant factors include a greater contact interface, more favorable estimated change in solvation energy, and greater number of interfacial H-bonds in MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 compared with MMP-10cd·TIMP-1. At the heart of the molecular interface, the mechanism of inhibition is conserved, but differences in molecular contact orientation and altered conformations of TIMP residues involved in specificity produce subtle differences in intermolecular packing and electrostatic interactions. It seems likely that in aggregate, small differences in steric and electrostatic complementarity involving many atoms spread over the intermolecular interface are responsible for the stronger inhibition of MMP-3 over MMP-10 by TIMP-1, and we speculate that similar forces determine the selectivity of TIMP-2.

Among the residues of TIMP-1 that display different conformations in the two complexes are Thr-2, Val-4, and Thr-98. Mutagenesis of each of these residues has been shown to have a large impact on the inhibitory specificity of TIMP-1. Thr-2 fills the MMP S1′ subsite, a major determinant of substrate specificity (18, 52), and site-directed mutagenesis of Thr-2 can dramatically alter the selectivity of TIMP-1 for different MMPs (67). Mutagenesis of Val-4, which binds in the MMP S3′ subsite, has similarly been found to modulate TIMP-1 specificity (68, 69), and Thr-98 is another TIMP-1 residue that when mutated can reshape inhibitory specificity (70). Given that alterations in the size, shape, or hydrophobicity of these residues can have a large impact on TIMP-1 binding affinities toward different MMPs, it is likely that the more subtle conformational changes that we observe in these residues in the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 structure are responsible for smaller differences in interface complementarity that affect the strength of binding.

Two stretches of TIMP-1 residues in our structure are disordered, including β-strand A and A-B loop residues 25–30 and B-C loop residues 50–57. The intrinsic flexibility of β-strand A and the A-B loop is further evidenced by the conformational heterogeneity of this region in comparisons of different structures. Gln-31 in our structure lies 12 Å distant from the same residue in the aligned MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structure (1UEA) (51), whereas in the N-TIMP-1 structures with MMP-1cd (2JOT) (57) and with MT1-MMPcd (3MA2) (59), this loop assumes an intermediate position closer to that seen in the solution structure of unbound TIMP-1 (71). Similarly, the B-C loop residues that lack defined structure in our complex are also fully disordered in the MT1-MMPcd/N-TIMP-1 complex (59), partially disordered in the MMP-1cd/N-TIMP-1 structure (2JOT), and possess very high B-factors in the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structure (51); this loop also shows divergence in the NMR ensemble (71).

A number of prior studies have highlighted the flexible nature of both TIMPs and MMPs and have explored the influence of flexibility and dynamics on binding affinities. NMR and isothermal titration calorimetry studies have shown that binding of MMP-3cd to N-TIMP-1 and N-TIMP-2 is accompanied by a net increase in entropy, due at least in part to binding-induced changes conferring greater backbone mobility on parts of the TIMP molecule distant from the intermolecular interface (72, 73). Molecular dynamics simulations investigating reasons for the failure of MT1-MMPcd to bind N-TIMP-1 and for the improved binding of a high affinity N-TIMP-1 mutant suggest that mobility is critical here, as well. It appears that excessive intrinsic flexibility at the N-TIMP-1 binding surface interferes with binding to MT1-MMPcd, which is itself unusually flexible throughout the S-loop and bulge edge segment that contact the TIMP AB and CD loops (59). Enhanced intramolecular H-bond stability at key positions of the binding surface stabilized the high affinity N-TIMP-1 mutant in a bound-like conformation, enhancing affinity for MT1-MMP (59).

Although our data do not give direct evidence of differences in dynamics between the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 and MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structures, it is very possible that such differences may exist and may contribute to differences in affinity between these complexes. For example, Thr-2 Oγ of TIMP-1 forms a hydrogen bond with Pro-221 oxygen in the MMP-3cd complex but not with the equivalent Pro-237 in the MMP-10cd complex. This Pro residue lies in the S1′-wall-forming segment of the MMP specificity loop, a key feature for molecular recognition but also a region of very high native mobility. We speculate that this hydrogen bond found in the MMP-3cd complex but not the MMP-10cd complex may help to stabilize the flexible specificity loop in a productive conformation during the process of binding, enhancing affinity. Future investigations incorporating solution studies or computational approaches may offer additional insights into the role of dynamics in this system.

An unexpected finding of our study is that closeness of MMP sequence homology may be a poor indicator of structural homology and susceptibility to inhibition by specific TIMPs. The stromelysins MMP-3 and MMP-10 are the most closely related in sequence of any MMPs, with 85% sequence identity in the catalytic domain, and yet do not appear to be more closely related than other MMP pairs in inhibition by TIMPs or in their TIMP-bound structures. For example, the r.m.s. deviation between analogous Cα atoms of the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 and MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 structures is 1.28 Å, and that between the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 and MMP-1cd·N-TIMP-1 is 1.35 Å, whereas the MMP-3cd·TIMP-1 and MMP-1cd·N-TIMP-1 structures are more similar, with an r.m.s. deviation of 0.67 Å. Surprisingly, the MMP-3 complex more closely resembles that of MMP-1, a collagenase, than that of the stromelysin MMP-10.

Such differences in structure and binding specificity among the stromelysins should prompt further investigations into the consequences of these differences for the physiological and pathological functions of these proteases. MMP-3 and MMP-10 appear to have distinct functions in wound healing, due at least in part to differential temporal and spatial expression patterns (8, 74). MMP-3 is further identified as playing a distinct role in mammary gland branching morphogenesis (75), whereas MMP-10 is uniquely important in vascular remodeling (10, 11). Given the differences that we have identified between the stromelysins in sensitivity to their physiological inhibitors, it is worth considering whether differential regulation at the level of enzyme inhibition may offer an additional explanation for the distinct physiological roles of MMP-3 and MMP-10. This possibility highlights the importance of continued biochemical and structural studies for defining the interactions between MMPs and TIMPs as well as with other endogenous inhibitors.

Beyond normal physiological activities, MMPs have been implicated in a number of diseases and play particularly critical roles in tumorigenesis, tumor progression, and metastasis (2, 76). MMP-10 in particular is up-regulated in human non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), where it is associated with poor clinical outcome (22, 77). We have identified MMP-10 as a major downstream effector of two NSCLC oncogenes, Kras and PKCι (22, 23). Silencing of MMP-10 expression in lung cancer cells blocks anchorage-independent growth and invasion; interestingly, recombinant MMP-10cd reconstitutes anchorage-independent growth and invasion, whereas MMP-3cd does not, indicating that MMP-10 must have a highly specific function in mediating cellular transformation (22). Silencing of MMP-10 expression also suppresses the enhanced self-renewal and tumorigenic properties of the subpopulation of lung cancer cells with stemlike characteristics (87), and we further find that genetic loss of Mmp10 suppresses tumorigenesis and tumor growth in mouse models of oncogenic Kras-mediated lung adenocarcinoma (23). In aggregate, our studies strongly support the idea that MMP-10 may offer a novel therapeutic target for intervention in NSCLC, and the insights into MMP-10 binding and inhibition offered by the present study could offer guidance in the development of appropriately selective inhibitors.

One strategy to develop more highly selective MMP inhibitors is protein engineering using the natural TIMPs as scaffolds or templates (3, 13). Efforts to engineer TIMPs for altered or enhanced specificity have shown substantial progress to date, both via structure-based mutagenic approaches primarily targeting key interfacial residues (67–70, 78–84) and most recently via screening of a phage display library of TIMP-2 mutants (85). An N-TIMP-1 mutant engineered to recognize MT1-MMP was found to be effective in blocking native MT1-MMP-mediated proteolysis in a variety of cell-based assays (86), further demonstrating the promising therapeutic prospects for modified recombinant TIMPs.

Our binding studies have revealed that native TIMPs are capable of distinguishing between the stromelysins and suggest that detailed analysis of the structure of the MMP-10cd·TIMP-1 complex can be used to identify engineering strategies to selectively increase the affinity of TIMP-1 for MMP-10. In this regard, we take particular note of the significant contacts between the N terminus of MMP-3cd and the AB loop of TIMP-1, which are absent in the complex with MMP-10cd. Interactions in this region have proven critical in modulating TIMP selectivity toward other MMPs. For example, replacement of the TIMP-1 AB loop with the much longer TIMP-2 AB loop has minimal impact on affinity toward MMP-1, which makes no natural contacts with the TIMP-1 AB loop, but substantially weakens affinity toward MMP-3cd, presumably by disrupting the favorable contacts with the N terminus of MMP-3cd (84). We speculate that optimization of the length and sequence of the TIMP AB loop to disrupt MMP-3 interactions while favoring MMP-10 interactions may be one useful step toward the development of MMP-10-selective TIMPs. Such selective inhibitors would be useful as experimental probes of MMP-10 function in a variety of physiological and pathological model systems and ultimately may be of therapeutic value in the treatment of NSCLC.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NCI, Grants R01 CA122086 (to D. C. R.) and R01 CA081436-14 (to A. P. F.). This work was also supported by Florida Department of Health Grants 08KN12 and 09BB17 (to E. S. R.) and 1BD01 (to J. B.) and by Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence Grant P50 CA116201 (principal investigator James Ingle). Diffraction data were measured at beamline X12-C of the National Synchrotron Light Source, which is supported by the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy and the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3V96) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- TIMP

- tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

- MMP-10cd

- MMP-10 catalytic domain

- MMP-3cd

- MMP-3 catalytic domain

- proMMP-3cd

- proMMP-3 catalytic domain

- MMPcd

- MMP catalytic domain

- H-bond

- hydrogen bond

- TLS

- translation/libration/screw

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- MT1-MMP

- membrane-type matrix metallopeptidase-1

- NSCLC

- non-small cell lung carcinoma.

REFERENCES

- 1. Murphy G., Nagase H. (2008) Progress in matrix metalloproteinase research. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 290–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Radisky E. S., Radisky D. C. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinase-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 15, 201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nagase H., Brew K. (2002) Engineering of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases mutants as potential therapeutics. Arthritis Res. 4, S51–S61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nagase H., Visse R., Murphy G. (2006) Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 562–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nicholson R., Murphy G., Breathnach R. (1989) Human and rat malignant tumor-associated mRNAs encode stromelysin-like metalloproteinases. Biochemistry 28, 5195–5203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakamura H., Fujii Y., Ohuchi E., Yamamoto E., Okada Y. (1998) Activation of the precursor of human stromelysin 2 and its interactions with other matrix metalloproteinases. Eur. J. Biochem. 253, 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bord S., Horner A., Hembry R. M., Compston J. E. (1998) Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) and stromelysin-2 (MMP-10) expression in developing human bone. Potential roles in skeletal development. Bone 23, 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saarialho-Kere U. K., Pentland A. P., Birkedal-Hansen H., Parks W. C., Welgus H. G. (1994) Distinct populations of basal keratinocytes express stromelysin-1 and stromelysin-2 in chronic wounds. The J. Clin. Invest. 94, 79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Windsor L. J., Grenett H., Birkedal-Hansen B., Bodden M. K., Engler J. A., Birkedal-Hansen H. (1993) Cell type-specific regulation of SL-1 and SL-2 genes. Induction of the SL-2 gene but not the SL-1 gene by human keratinocytes in response to cytokines and phorbolesters. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 17341–17347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang S., Young B. D., Li S., Qi X., Richardson J. A., Olson E. N. (2006) Histone deacetylase 7 maintains vascular integrity by repressing matrix metalloproteinase 10. Cell 126, 321–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodriguez J. A., Orbe J., Martinez de Lizarrondo S., Calvayrac O., Rodriguez C., Martinez-Gonzalez J., Paramo J. A. (2008) Metalloproteinases and atherothrombosis. MMP-10 mediates vascular remodeling promoted by inflammatory stimuli. Front. Biosci. 13, 2916–2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gomis-Rüth F. X., Maskos K., Betz M., Bergner A., Huber R., Suzuki K., Yoshida N., Nagase H., Brew K., Bourenkov G. P., Bartunik H., Bode W. (1997) Mechanism of inhibition of the human matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-1 by TIMP-1. Nature 389, 77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker A. H., Edwards D. R., Murphy G. (2002) Metalloproteinase inhibitors. Biological actions and therapeutic opportunities. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3719–3727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coussens L. M., Fingleton B., Matrisian L. M. (2002) Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer. Trials and tribulations. Science 295, 2387–2392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turk B. (2006) Targeting proteases. Successes, failures and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 785–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burrage P. S., Brinckerhoff C. E. (2007) Molecular targets in osteoarthritis. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Curr. Drug Targets 8, 293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fingleton B. (2008) MMPs as therapeutic targets. Still a viable option? Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 61–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Overall C. M., Kleifeld O. (2006) Towards third generation matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Br J. Cancer 94, 941–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu J., Van den Steen P. E., Sang Q. X., Opdenakker G. (2007) Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 480–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Themsche C., Alain T., Kossakowska A. E., Urbanski S., Potworowski E. F., St-Pierre Y. (2004) Stromelysin-2 (matrix metalloproteinase 10) is inducible in lymphoma cells and accelerates the growth of lymphoid tumors in vivo. J. Immunol. 173, 3605–3611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gill J. H., Kirwan I. G., Seargent J. M., Martin S. W., Tijani S., Anikin V. A., Mearns A. J., Bibby M. C., Anthoney A., Loadman P. M. (2004) MMP-10 is overexpressed, proteolytically active, and a potential target for therapeutic intervention in human lung carcinomas. Neoplasia 6, 777–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frederick L. A., Matthews J. A., Jamieson L., Justilien V., Thompson E. A., Radisky D. C., Fields A. P. (2008) Matrix metalloproteinase-10 is a critical effector of protein kinase Ciota-Par6α-mediated lung cancer. Oncogene 27, 4841–4853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Regala R. P., Justilien V., Walsh M. P., Weems C., Khoor A., Murray N. R., Fields A. P. (2011) Matrix metalloproteinase-10 promotes Kras-mediated bronchio-alveolar stem cell expansion and lung cancer formation. PloS One 6, e26439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deraz E. M., Kudo Y., Yoshida M., Obayashi M., Tsunematsu T., Tani H., Siriwardena S. B., Keikhaee M. R., Qi G., Iizuka S., Ogawa I., Campisi G., Lo Muzio L., Abiko Y., Kikuchi A., Takata T. (2011) MMP-10/stromelysin-2 promotes invasion of head and neck cancer. PloS One 6, e25438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crombez L., Marques B., Lenormand J. L., Mouz N., Polack B., Trocme C., Toussaint B. (2005) High level production of secreted proteins. Example of the human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337, 908–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee J. E., Fusco M. L., Saphire E. O. (2009) An efficient platform for screening expression and crystallization of glycoproteins produced in human cells. Nat. Protoc. 4, 592–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suzuki K., Kan C. C., Hung W., Gehring M. R., Brew K., Nagase H. (1998) Expression of human pro-matrix metalloproteinase 3 that lacks the N-terminal 34 residues in Escherichia coli. Autoactivation and interaction with tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1). Biol. Chem. 379, 185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marcy A. I., Eiberger L. L., Harrison R., Chan H. K., Hutchinson N. I., Hagmann W. K., Cameron P. M., Boulton D. A., Hermes J. D. (1991) Human fibroblast stromelysin catalytic domain. Expression, purification, and characterization of a C-terminally truncated form. Biochemistry 30, 6476–6483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagase H., Enghild J. J., Suzuki K., Salvesen G. (1990) Stepwise activation mechanisms of the precursor of matrix metalloproteinase 3 (stromelysin) by proteinases and (4-aminophenyl)mercuric acetate. Biochemistry 29, 5783–5789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Suzuki K., Enghild J. J., Morodomi T., Salvesen G., Nagase H. (1990) Mechanisms of activation of tissue procollagenase by matrix metalloproteinase 3 (stromelysin). Biochemistry 29, 10261–10270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nagase H. (1995) Human stromelysins 1 and 2. Methods Enzymol. 248, 449–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weingarten H., Martin R., Feder J. (1985) Synthetic substrates of vertebrate collagenase. Biochemistry 24, 6730–6734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weingarten H., Feder J. (1985) Spectrophotometric assay for vertebrate collagenase. Anal. Biochem. 147, 437–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murphy G., Willenbrock F. (1995) Tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloendopeptidases. Methods Enzymol. 248, 496–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laskowski M., Jr., Sealock R. W. (1971) in The Enzymes (Boyer P. D., ed) Vol. 3, pp. 375–473, Academic Press, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 36. Radisky E. S., King D. S., Kwan G., Koshland D. E., Jr. (2003) The role of the protein core in the inhibitory power of the classic serine protease inhibitor, chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Biochemistry 42, 6484–6492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Longstaff C., Campbell A. F., Fersht A. R. (1990) Recombinant chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Expression, kinetic analysis of inhibition with α-chymotrypsin and wild-type and mutant subtilisin BPN′, and protein engineering to investigate inhibitory specificity and mechanism. Biochemistry 29, 7339–7347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang W., Suzuki K., Nagase H., Arumugam S., Van Doren S. R., Brew K. (1996) Folding and characterization of the amino-terminal domain of human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) expressed at high yield in E. coli. FEBS Lett. 384, 155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salameh M. A., Soares A. S., Hockla A., Radisky E. S. (2008) Structural basis for accelerated cleavage of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI) by human mesotrypsin. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4115–4123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2005) Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61, 458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Perrakis A., Harkiolaki M., Wilson K. S., Lamzin V. S. (2001) ARP/wARP and molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 1445–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perrakis A., Morris R., Lamzin V. S. (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot. Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Winn M. D., Isupov M. N., Murshudov G. N. (2001) Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Radisky E. S., Kwan G., Karen Lu C. J., Koshland D. E., Jr. (2004) Binding, proteolytic, and crystallographic analyses of mutations at the protease-inhibitor interface of the subtilisin BPN′/chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 complex. Biochemistry 43, 13648–13656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Radisky E. S., Lu C. J., Kwan G., Koshland D. E., Jr. (2005) Role of the intramolecular hydrogen bond network in the inhibitory power of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Biochemistry 44, 6823–6830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Salameh M. A., Robinson J. L., Navaneetham D., Sinha D., Madden B. J., Walsh P. N., Radisky E. S. (2010) The amyloid precursor protein/protease nexin 2 Kunitz inhibitor domain is a highly specific substrate of mesotrypsin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 1939–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gomis-Rüth F. X. (2009) Catalytic domain architecture of metzincin metalloproteases. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15353–15357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tallant C., Marrero A., Gomis-Rüth F. X. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinases. Fold and function of their catalytic domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bertini I., Calderone V., Fragai M., Luchinat C., Mangani S., Terni B. (2004) Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of human matrix metalloproteinase 10. J. Mol. Biol. 336, 707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brew K., Dinakarpandian D., Nagase H. (2000) Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases. Evolution, structure, and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1477, 267–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Maskos K., Bode W. (2003) Structural basis of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases. Mol. Biotechnol. 25, 241–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fernandez-Catalan C., Bode W., Huber R., Turk D., Calvete J. J., Lichte A., Tschesche H., Maskos K. (1998) Crystal structure of the complex formed by the membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase with the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2, the soluble progelatinase A receptor. EMBO J. 17, 5238–5248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Iyer S., Wei S., Brew K., Acharya K. R. (2007) Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in complex with the inhibitory domain of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 364–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maskos K., Lang R., Tschesche H., Bode W. (2007) Flexibility and variability of TIMP binding. X-ray structure of the complex between collagenase-3/MMP-13 and TIMP-2. J. Mol. Biol. 366, 1222–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grossman M., Tworowski D., Dym O., Lee M. H., Levy Y., Murphy G., Sagi I. (2010) The intrinsic protein flexibility of endogenous protease inhibitor TIMP-1 controls its binding interface and affects its function. Biochemistry 49, 6184–6192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gomis-Rüth F. X., Botelho T. O., Bode W. (2012) A standard orientation for metallopeptidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1824, 157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhou P., Tian F., Lv F., Shang Z. (2009) Geometric characteristics of hydrogen bonds involving sulfur atoms in proteins. Proteins 76, 151–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu D., Tsai C. J., Nussinov R. (1997) Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges across protein-protein interfaces. Protein Eng. 10, 999–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xu D., Lin S. L., Nussinov R. (1997) Protein binding versus protein folding. The role of hydrophilic bridges in protein associations. J. Mol. Biol. 265, 68–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sheinerman F. B., Norel R., Honig B. (2000) Electrostatic aspects of protein-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rozas I., Alkorta I., Elguero J. (1998) Bifurcated hydrogen bonds: Three-centered interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 9925–9932 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Torshin I. Y., Weber I. T., Harrison R. W. (2002) Geometric criteria of hydrogen bonds in proteins and identification of “bifurcated” hydrogen bonds. Protein Eng. 15, 359–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Meng Q., Malinovskii V., Huang W., Hu Y., Chung L., Nagase H., Bode W., Maskos K., Brew K. (1999) Residue 2 of TIMP-1 is a major determinant of affinity and specificity for matrix metalloproteinases but effects of substitutions do not correlate with those of the corresponding P1′ residue of substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10184–10189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lee M. H., Rapti M., Murphy G. (2003) Unveiling the surface epitopes that render tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 inactive against membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40224–40230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wei S., Chen Y., Chung L., Nagase H., Brew K. (2003) Protein engineering of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) inhibitory domain. In search of selective matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9831–9834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lee M. H., Rapti M., Knaüper V., Murphy G. (2004) Threonine 98, the pivotal residue of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 in metalloproteinase recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17562–17569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wu B., Arumugam S., Gao G., Lee G. I., Semenchenko V., Huang W., Brew K., Van Doren S. R. (2000) NMR structure of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 implicates localized induced fit in recognition of matrix metalloproteinases. J. Mol. Biol. 295, 257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Arumugam S., Gao G., Patton B. L., Semenchenko V., Brew K., Van Doren S. R. (2003) Increased backbone mobility in β-barrel enhances entropy gain driving binding of N-TIMP-1 to MMP-3. J. Mol. Biol. 327, 719–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wu Y., Wei S., Van Doren S. R., Brew K. (2011) Entropy increases from different sources support the high affinity binding of the N-terminal inhibitory domains of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases to the catalytic domains of matrix metalloproteinases-1 and -3. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16891–16899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gill S. E., Parks W. C. (2008) Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Regulators of wound healing. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 1334–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wiseman B. S., Sternlicht M. D., Lund L. R., Alexander C. M., Mott J., Bissell M. J., Soloway P., Itohara S., Werb Z. (2003) Site-specific inductive and inhibitory activities of MMP-2 and MMP-3 orchestrate mammary gland branching morphogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 162, 1123–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kessenbrock K., Plaks V., Werb Z. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinases. Regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 141, 52–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cho N. H., Hong K. P., Hong S. H., Kang S., Chung K. Y., Cho S. H. (2004) MMP expression profiling in recurred stage IB lung cancer. Oncogene 23, 845–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Butler G. S., Hutton M., Wattam B. A., Williamson R. A., Knäuper V., Willenbrock F., Murphy G. (1999) The specificity of TIMP-2 for matrix metalloproteinases can be modified by single amino acid mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 20391–20396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Williamson R. A., Hutton M., Vogt G., Rapti M., Knäuper V., Carr M. D., Murphy G. (2001) Tyrosine 36 plays a critical role in the interaction of the AB loop of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 with matrix metalloproteinase-14. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32966–32970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lee M. H., Verma V., Maskos K., Nath D., Knäuper V., Dodds P., Amour A., Murphy G. (2002) Engineering N-terminal domain of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-3 to be a better inhibitor against tumour necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme. Biochem. J. 364, 227–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lee M. H., Maskos K., Knäuper V., Dodds P., Murphy G. (2002) Mapping and characterization of the functional epitopes of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-3 using TIMP-1 as the scaffold. A new frontier in TIMP engineering. Protein Sci. 11, 2493–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lee M. H., Rapti M., Murphy G. (2004) Delineating the molecular basis of the inactivity of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 against tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45121–45129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lee M. H., Rapti M., Murphy G. (2005) Total conversion of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) for specific metalloproteinase targeting. Fine-tuning TIMP-4 for optimal inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}-converting enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15967–15975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hamze A. B., Wei S., Bahudhanapati H., Kota S., Acharya K. R., Brew K. (2007) Constraining specificity in the N-domain of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1. Gelatinase-selective inhibitors. Protein Sci. 16, 1905–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bahudhanapati H., Zhang Y., Sidhu S. S., Brew K. (2011) Phage display of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP-2). Identification of selective inhibitors of collagenase-1 (metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1)). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31761–31770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lee M. H., Atkinson S., Rapti M., Handsley M., Curry V., Edwards D., Murphy G. (2010) The activity of a designer tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 against native membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) in a cell-based environment. Cancer Lett. 290, 114–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Justilien V., Regala R. P., Tseng I.-C, Walsh M. P., Batra J., Radisky E. S., Murray N. R., Fields A. P. (2012) Matrix metalloproteinase-10 is required for lung cancer stem cell maintenance, tumor initiation, and metastatic potential. PLoS One, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]