Background: A signaling or S-helix often connects upstream receiver and downstream output domains.

Results: Characterization of the S-helix in an adenylyl cyclase from Arthrospira maxima demonstrates an autonomous role of the S-helix in sensory signaling.

Conclusion: The S-helix determines the cytoplasmic signal.

Significance: The ubiquitous S-helix is a distinct module involved in signal transduction.

Keywords: Adenylate Cyclase (Adenylyl Cyclase), Chemotaxis, Membrane Enzymes, Signal Transduction, Signaling, HAMP Domain, S-helix, Signal Reversion, Tsr

Abstract

A signaling or S-helix has been identified as a conserved, up to 50-residue-long segment in diverse sensory proteins (1). It is present in all major bacterial lineages and in euryarchea and eukaryotes (1). A bioinformatic analysis shows that it connects upstream receiver and downstream output domains, e.g. in histidine kinases and bacterial adenylyl cyclases. The S-helix is modeled as a two-helical parallel coiled coil. It is predicted to prevent constitutive activation of the downstream signaling domains in the absence of ligand-binding (1). We identified an S-helix of about 25 residues in the adenylyl cyclase CyaG from Arthrospira maxima. Deletion of the 25 residue segment connecting the HAMP and catalytic domains in a chimera with the Escherichia coli Tsr receptor changed the response to serine from inhibition to stimulation. Further examination showed that a deletion of one to three heptads plus a presumed stutter, i.e. 1, 2, or 3 × 7 + 4 amino acids, is required and sufficient for signal reversion. It was not necessary that the deletions be continuous, as removal of separated heptads and presumed stutters also resulted in signal reversion. Furthermore, insertion of the above segments between the HAMP and cyclase catalytic domains similarly resulted in signal reversion. This indicates that the S-helix is an independent, segmented module capable to reverse the receptor signal. Because the S-helix is present in all kingdoms of life, e.g. in human retinal guanylyl cyclase, our findings may be significant for many sensory systems.

Introduction

Sensing the outside environment is a prerequisite for the evolution of all forms of life. Thus, it is self-evident that sensory signal transduction systems evolved early on in prokaryotes (2). Using the steadily increasing availability of fully sequenced genomes, bioinformatic studies have identified two major primordial sensory signal transduction systems in bacteria, one-component systems, which are single proteins that combine sensor and output domain, and two-component systems, in which a sensor and transmitter protein interacts with a separate receiver and output protein (3–7). The majority of one-component systems are intracellular sensors, whereas two-component systems, as membrane-bound sensory systems, predominantly monitor the environment (2, 4). Both systems share a large repertoire of sensory and output domains (8–10). Considering the thousands of individual signal transduction systems that have been identified in bacteria, in most instances the chemical nature of the ligands are unknown. The principal types of output activities for one- and two-component systems are regulation of DNA transcription by helix-turn-helix domains (85%), histidine kinases, and adenylyl cyclases (8).

In several instances it has been demonstrated that between one- and two-component signaling systems individual domains are interchangeable without loss of function (11–16). In many signal transduction systems, HAMP2 domains (histidine kinase, adenylyl cyclase, methyl-accepting proteins of chemotaxis, protein-phosphatases (17)), which are four-bundle parallel coiled coils of about 55 residues, are interspaced between sensory and output domains (18–19). We have studied HAMP-mediated signal transduction across the cytoplasmic membrane in vitro and in vivo using chimeras composed of the E. coli chemotaxis receptor for serine (Tsr) as a sensor, different HAMP domains, and the AC catalytic domains CyaG from Arthrospira platensis and Rv3645 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (11, 16, 18, 20). In these constructs, serine inhibited AC activity in vitro and in vivo (11, 20). So far the structures of a complete one-component or an input protein of a two-component system are unavailable. The periplasmic Tar receptor of E. coli has been elucidated and characterized extensively (21–26). Signaling through the transmembrane spans has been modeled (27). HAMP domain structures and the structure of the output domain of Tsr are available (18–19, 28). The cable connecting the cytoplasmic exit of the second transmembrane span to the HAMP domain and the α-helices and the connector of the HAMP domain have been characterized by genetic and biochemical studies (29–31).

On the basis of bioinformatics a peculiar linker region, termed signaling or S-helix, was identified that often connects the C terminus of the HAMP domain to an output domain (1). In general, the S-helix connects upstream receiver and downstream catalytic domains in a variety of settings with the exception of chemotaxis proteins (1). So far, the understanding of the S-helix focused more on its structural rather than biochemical and functional properties (1, 32–34). Here our goal was to better characterize the function in the context of regulation of the A. maxima CyaG AC. We biochemically analyzed the S-helix present between the HAMP and the catalytic domain of CyaG AC. We demonstrate that the S-helix can determine the cytoplasmic outcome of receptor stimulation. The presence of the S-helix in all kingdoms of life, among others also in the human retinal guanylyl cyclase, highlights the significance of this finding.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Radiochemicals were from Hartmann Analytik and GE Healthcare. Enzymes were purchased from either Roche Diagnostics or New England Biolabs. Other chemicals were from Sigma, Roche Diagnostics, Roth, and Merck.

Plasmid Construction

A. maxima AC CyaG (GenBankTM accession number ZP_03272770) was available in the laboratory (11). Individual signaling modules, i.e. receptor and HAMP domains from the E. coli serine chemotaxis receptor Tsr were connected as described (11). The domains used were the Tsr receptor domain, residues 1–215; the Tsr HAMP domain, residues 216–268; the AC CyaG HAMP domain, residues 370–430; the CyaG S-helix, residues 431–455; and the AC CyaG catalytic domain, residues 456–672 (Fig. 1, top). The chimeras were cloned using standard molecular biology methods. Silent restriction sites were introduced where necessary. Generally, 5′ BamHI and 3′ HindIII sites were used for cloning in conjunction with internal pairs of sense and antisense primers. In consecutive PCR reactions (fusion PCRs), the respective preceding constructs were used as templates. The DNA products were restricted at their BamHI and HindIII sites and inserted into pQE30 or pQE80L, thus adding an N-terminal MRGSH6GS tag. The correctness of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The construct Tsr(1–215)-HAMP-ACCyaG(370–672) was available in the laboratory (11).

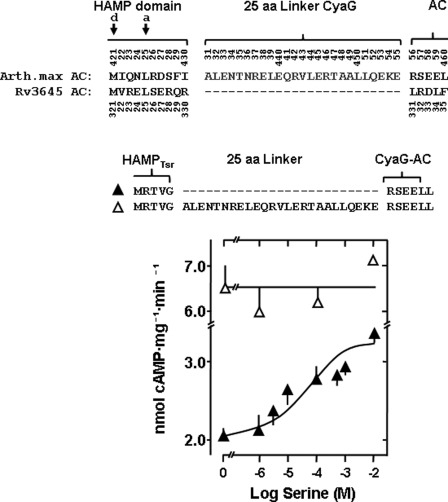

FIGURE 1.

Identification of the S-helix in the adenylyl cyclase CyaG from A. maxima. Top, the alignment comprises the C-terminal end of the HAMP domains and the start of the catalytic domains of the ACs CyaG from A. maxima (GI:209524220) and Rv3645 from M. tuberculosis (GI:15610781). The 25-residue segment connecting the HAMP and the output domains in CyaG is missing in Rv3645 AC. The arrows mark the last d and a heptad residues of the respective HAMP domains. The most prominent signature residues in the S-helix are Leu439/Glu440 and 445ERT447. aa, amino acid. Bottom, AC activities of the chimeras consisting of the Tsr receptor and HAMP domain connected with the CyaG catalytic domain (△) is not affected by serine, whereas the chimera shortened by the 25-residue S-helix (▴) is activated (maximal activation 64 ± 8%, EC50 = 24 ± 29 μm serine, p < 0.001 basal activity versus + 10 mm serine, n = 8).

Expression and Purification of Proteins

Expression plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)[pRep4]. Overnight precultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (20 g/liter) at 37 °C containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. 200 ml of LB broth (with antibiotics) was inoculated with 10 ml of a preculture and grown at 30 °C. At an A600 of 0.5–0.7, expression was induced with 100 μm isopropyl thio-β-d-galactoside for 5 h at 22 °C. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 3200 × g (15 min), washed once with 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8) and stored at −80 °C. For preparation of membrane fractions, cells were suspended in 25 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, 1.6 mm 3-thioglycerol (pH 8)) and disintegrated using a French press (1100 p.s.i.). Cell debris was removed at 3,000 × g for 30 min, and membranes were sedimented at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. Membranes were suspended in membrane buffer (40 mm Tris/HCl (pH8), 1.6 mm 3-thioglycerol, 20% glycerol) and assayed for AC activity. Empty vector controls were run routinely.

Western Blotting

The integrity of expressed recombinant membrane proteins was examined by Western blotting. Membrane fractions were mixed with sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE (12.5%). For Western blots proteins were blotted onto PVDF membranes and probed with an ArgGlySer-His4-antibody (Qiagen) and with a 1:5000 dilution of a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Dianova). Peroxidase detection was with the ECL Plus kit (GE Healthcare). The Western blot analyses for constructs used in Figs. 1–8 are shown in supplemental Fig. 1S). All chimeras were expressed as undegraded, membrane-bound proteins.

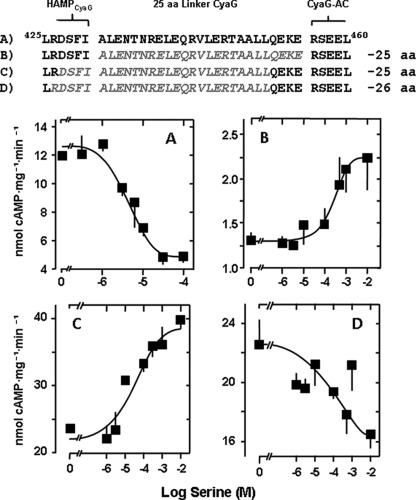

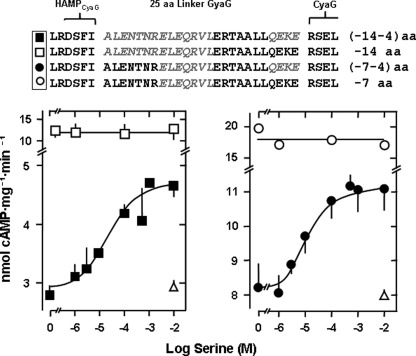

FIGURE 2.

Deletion of the S-helix in the CyaG adenylyl cyclase results in signal reversion of Tsr receptor stimulation. Top panel, partial sequence of CyaG HAMP-S-helix. Sequences in gray in B, C, and D indicate respective deletions. aa, amino acids. A, full-length parent chimera Tsr1–215-CyaG370–672 is inhibited by serine (maximal inhibition 58 ± 5%, IC50 = 6 ± 3 μm serine, n = 4). B, parent chimera shortened by 25 residues is activated by serine (maximal activation is 68 ± 18%, EC50 = 305 ± 0 μm serine, n = 4). C, shifting of the 25 residue deletion upstream by four residues (maximal activation 66 ± 1%, EC50 = 26 ± 24 μm serine, n = 4). D, deletion of 26 residues restores serine inhibition of parent construct (maximal inhibition is 26 ± 1%, IC50 = 19 ± 3 μm serine, n = 4).

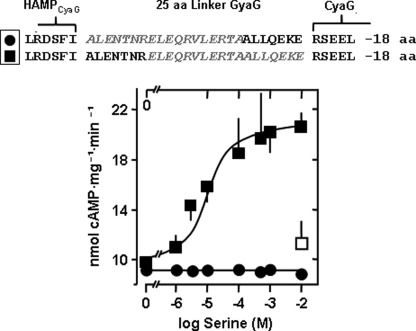

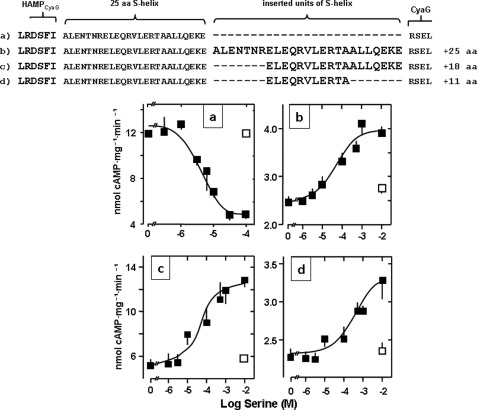

FIGURE 3.

Deletion of appropriately positioned 18 residues of the S-helix reverses the signal of the Tsr receptor. Top panel, deletions are marked in gray. Deletion of the proximal 18 residues (●) abrogate serine signaling (n = 6). Deletion of the distal 18 residues (■) leads to activation by serine (maximal activation 109 ± 8%, EC50 = 6 ± 2 μm serine, n = 4). The □ is a control with aspartate. aa, amino acid.

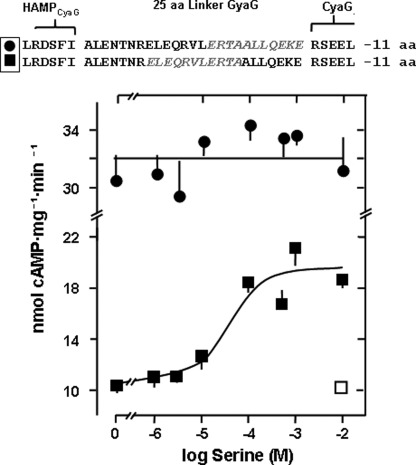

FIGURE 4.

Deletion of 11 residues of the S-helix reverses the signal of Tsr receptor stimulation. Top panel, deletions are printed gray. Deletion of the distal 11 residues stops signaling (●, n = 4). Deletion of 11 residues in the middle of the S-helix (■) allow serine activation (maximal activation 84 ± 19%, EC50 = 24 ± 2 μm serine, n = 6). The □ is a control with aspartate. aa, amino acid.

FIGURE 5.

For signal reversion deletions need not to be continuous. Top panel, deletions are printed in gray. aa, amino acid. Bottom left panel, deletion of two proximal heptads and the QEKE motif one heptad downstream results in serine activation (maximal activation 53 ± 4%, EC50 = 29 ± 33 μm serine, n = 6). △, control with aspartate. In a further control only the two proximal heptads were deleted. This thwarted regulation by serine (□, n = 4). Bottom right panel, deletion of 11 residues as two separated segments resulted in serine activation (●, maximal activation 35 ± 5%, EC50 = 9 ± 2 μm serine, n = 6). △, control with aspartate. Deletion of only the second heptad of the S-helix resulted in an unresponsive chimera (○; n = 4).

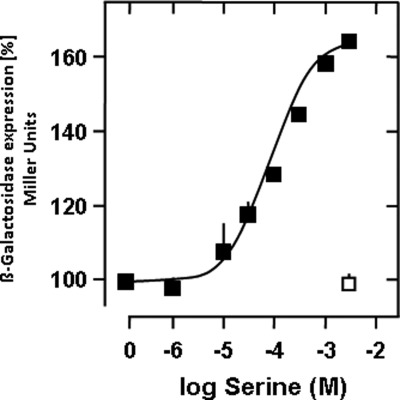

FIGURE 6.

Insertions of S-helix modules change the Tsr receptor signal. Top panel, modules of the S-helix inserted into CyaG after the QEKE motif are printed large. aa, amino acid. A, the parent chimera is inhibited by serine. B, insertion of the 25-residue S-helix leads to signal reversion (maximal activation 59 ± 7%, EC50 = 67 ± 45 μm serine, n = 4). C, insertion of an 18-residue unit of the S-helix (maximal activation 150 ± 15%, EC50 = 80 ± 60 μm serine, n = 6). D, insertion of an 11-residue unit of the S-helix (maximal activation 45 ± 6%, EC50 = 744 ± 2 μm serine, n = 6). □, respective controls with aspartate.

FIGURE 7.

In vivo induction of β-galactosidase via serine-stimulated cAMP formation in a chimera with linker segment insertion. E. coli cya transformed with the chimera of Fig. 6C was incubated with various serine concentrations that induced β-galactosidase expression. 100% corresponds to β-galactosidase activity without serine addition (maximal activation 65 ± 2%, EC50 = 152 ± 33 μm, n = 2). □, control with 3 mm aspartate in the medium.

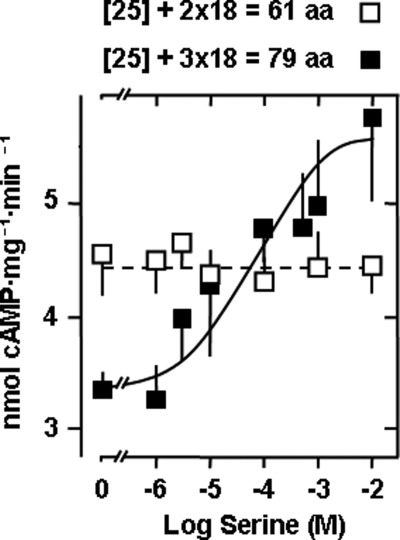

FIGURE 8.

Insertion of additional two and three S-helix modules into a Tsr-CyaG chimera affects the signal of Tsr receptor stimulation. The sequence (ELEQRVLERTAALLQEKE) was inserted after the QEKE motif twice (□) and thrice (■). Maximal activation by serine was 71 ± 9%, and the EC50 was 48 ± 6 μm (n = 4).

Adenylyl Cyclase Assay

AC activity was determined at 37 °C for 10 min (35). Standard reactions of 100 μl contained 20 μg of membrane protein, 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8), 21% glycerol, 3 mm MnCl2, 750 μm [α-32P]-ATP, and 2 mm [2,8-3H]-cAMP to monitor yield during product purification. Creatine kinase and creatine phosphate were used as an ATP regenerating system. Data shown are the means ± S.E. with the numbers of individual experiments indicated (≥ 4 for all points). Student's t tests were used for statistical evaluation when deemed necessary. A p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

β-Galactosidase Assay

Constructs transformed into cya mutants were grown in LB media at 37 °C for 15 h. Cells were collected (15 min, 3,000 × g), diluted to an A of 0.2 in M63 (36) containing 0.6% glycerol and 30 μg/ml ampicillin (pH 7). 2.5-ml samples were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. Induction of β-galactosidase was with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside ± different concentrations of serine or aspartate. After 90 min, cells were collected by centrifugation, and pellets were stored at −20 °C. β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described with slight modifications (37). Cell sediments were suspended in 1 ml of assay buffer (60 mm Na2HPO4, 40 mm NaH2PO4, 1 mm MgSO4, and 5 mm DTT). 10 μl of 0.1% SDS and 20 μl of chloroform were added. Samples were incubated for 5 min at 28 °C. The enzyme reaction was started by addition of 200 μl of o-nitrophenyl-galactose (2.2 mm) and stopped by addition of 0.5 ml of 1 m Na2CO3. The A405 was measured in the supernatant of a 4-min spin (12,000 × g). Data were evaluated in Miller units and normalized (37).

RESULTS

In bacterial genomes 49 bacterial ACs from 26 species are predicted to possess two transmembrane spans that frame a putative periplasmic receptor domain of around 150 residues, a cytoplasmic HAMP domain, and a class III AC catalytic domain (38–39). One major difference in these 49 ACs are variations in the linker between the HAMP and the AC domains. The linker lengths range from 32 (e.g. Magnetospirillum magneticum, Q2W7Z5) to 73 residues (Stappia aggregata, A0NLS4). Another 19 bacterial ACs from six species are predicted to have six transmembrane spans followed by a canonical cytoplasmic HAMP domain and a class IIIb AC. The length of the linker is uniformly 39 residues (with two 45 residue exceptions, data not shown). The tripartite domain organization of HAMP-containing bacterial ACs resembles bacterial chemotaxis proteins (methyl-accepting proteins of chemotaxis) such as Tsr for serine from E. coli (40). Functional chimeras between these methyl-accepting proteins of chemotaxis and ACs have been generated (11, 16, 20).

The function of such tripartite chimeras critically depends on the precise determination of domain boundaries. Thus, we have noted that a chimera that has the receptor and HAMP domain from Tsr joined to the cyanobacterial A. maxima CyaG AC was not regulated, whereas a similar chimera using both the HAMP and AC domains from CyaG was inhibited by serine (11). This indicated that the origin of the HAMP domain and/or the type of connection between HAMP and AC might be important for signal propagation. In these former studies we mainly used the membrane-bound mycobacterial AC Rv3645 for generation of functional chimeras with the Tsr receptor domain and demonstrated that all chimeras were inhibited by serine in a concentration-dependent fashion (11, 16). A comparison of the linker sequences between the respective HAMP and catalytic domains from the ACs from A. maxima (CyaG) and M. tuberculosis (Rv3645) identified a 25-residue segment in CyaG that is absent in the AC Rv3645 (Fig. 1, top). This segment has the signature residues identifying it as an S-helix (1). To examine the role of this S-helix in signaling, we constructed chimeras with the receptor and HAMP domains from Tsr and the catalytic domain of CyaG with and without the 25-residue segment Ala-431-Glu-455. Although the construct with the S-helix was not regulated by serine as reported earlier for a similar chimera (11), most surprisingly, we observed that without the 25-residue segment CyaG AC activity was activated by serine in a concentration-dependent manner; i.e. the receptor signal was reverted, in stark contrast to all past chimeras (Fig. 1, bottom) (11, 16, 20). This indicated that the linker sequence between HAMP and cyclase domains might be critical for cytoplasmic signal processing. The HAMP domain is thought to operate as a cytoplasmic receiver for the transmembrane signal and as a transmitter to the downstream output domain. The above data would support the hypothesis that the S-helix between the HAMP and AC domains might constitute an additional signal processing unit. Therefore, we examined the role of this 25-residue segment of CyaG using the background of the CyaG HAMP and AC domains which were N-terminally joined to the Tsr serine receptor. Formerly, such a chimera was shown to be inhibited by serine (Fig. 2A) (11).

When we removed the 25-residue segment between CyaG HAMP and AC (Ala-431-Glu-455), we observed signal reversion as noted above. AC activity was stimulated by serine in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). Stimulation was specific, as 10 mm aspartate had no effect (data not shown). The increase in AC activity was 68%. The EC50 at 305 μm was rather high. Because the assignment of the boundary between the HAMP domain and the linker is somewhat arbitrary, we shifted the 25-residue deletion by four residues into the direction of the HAMP domain (Asp-427-Leu-451). Thus, we obtained a second chimera that was specifically activated by serine. Although the efficacy of activation was identical to the former construct (66% versus 68% activation), the potency of serine was enhanced more than 10-fold (EC50 = 26 μm versus 305 μm serine, Fig. 2C). Extending the deletion by a single residue (Arg-426-Leu-451), thus generating a 26-residue deletion, resulted in a slight concentration-dependent inhibition by serine of 26% (IC50 = 19 μm, Fig. 2D). This indicated that signal reversion may be coupled to a specific length-defined segment.

The next question was whether, for signal sign reversion, the removal of 25 residues was a minimal requirement. A secondary structure prediction toolkit indicated that the 25-residue sequence Ile-422-Arg-447 has a high propensity (0.979) for coiled coil formation (41). Within the 25-residue linker, which we arbitrarily defined to start with Ala-431, this would formally translate into three heptads and a four-residue stutter (42). Stutters locally transform the canonical knobs-into-holes packing of a coiled coil into a knobs-to-knobs interaction (43). It has been suggested that in two-stranded coiled coils, only alanine or glycine might fit into such a knob-to-knob interaction (43). Analysis of the 25-residue linker by COIL and MARCOIL (41) or by visual inspection failed to recognize a stutter sequence. Therefore, we next removed 18 residues (Glu-438-Glu-455) and retained the first heptad (Ala-431-Arg-437) of the segment (Fig. 3) formally corresponding to removal of two heptads and a four- residue stutter. The chimera was stimulated by serine more potently than the initial −25 residue construct (Fig. 3). Maximal stimulation was 109%, and the EC50 for serine dropped from 305 μm to 6.3 μm (compare Figs. 2B and 3). 10 mm aspartate was without effect. In a further construct we moved the deletion of the 18 residues one heptad upstream (Ala-431-Ala-448) and retained the last seven residues of the 25-residue segment (Ala-449-Glu-455). Although this chimera displayed robust AC activity, indicating correct protein folding, it was unaffected by serine (Fig. 3). The data then indicated that only a precisely positioned deletion can cause signal reversion and that the minimal conformational processing unit consists of less than 25 residues.

Does the Glu-438-Glu-455 segment constitute the minimal number and positional distinct segment, the deletion of which is essential to cause signal reversion? Next, we deleted the posterior 11 residues (Glu-445-Glu455) and retained the anterior 14 residue segment (Ala-431-Leu-444) (Fig. 4). The construct was well expressed, showed excellent AC activity, yet regulation of enzyme activity was absent (Fig. 4). This was somewhat surprising, as we had speculated that the 452QEKE455 motif might comprise the suspected four-residue stutter sequence. In the following chimera, we moved the 11-residue deletion by one heptad upstream; i.e. the anterior and posterior heptads of the 25-residue segment were retained, and the 11 residues Glu-438-Ala-448 were deleted. AC activity of the recombinant protein was 10 nmol cAMP/mg × min. It was stimulated 84% by serine. The EC50 was 30 μm. 10 mm aspartate as a control had no effect (Fig. 4). This data conclusively ruled out that the 452QEKE455 motif might constitute an indispensible stutter sequence and established the 11-residue element as sufficient for signal processing and signal reversion.

In earlier studies with the nitrate sensor kinase NarX from E. coli, this broader region was characterized by consecutive deletions of individual heptads and of presumed individual four residue stutter sequences (44). Some of these mutations affected signaling as recorded by β-galactosidase determinations, yet signal reversion was not found (32). We carried out a similar heptad deletion scan of the 25-residue S-helix in CyaG (see supplemental Fig. 2S). All nine constructs were well expressed and had robust AC activities. However, none was affected by up to 10 mm serine. Similarly, we made two constructs with 439LEQR442 or 452QEKE455 deletions that we suspected might serve as stutters. Both were well expressed, had AC activities around 20 nmol cAMP/mg × min, yet regulation by serine was absent (supplemental Fig. 2S). The experiments excluded that the deletion of a single heptad or a stutter might be sufficient for reversion of the Ser receptor signal arriving at the AC output domain. It appeared that for signal reversion the removal of a distinct 3 × 7 + 4, 2 × 7 + 4, or 7 + 4 residue segment was required; i.e. up to three heptads and a presumed four-residue stutter. Further, the common denominator for all constructs that were stimulated by serine was that it must include the deletion of the 438ELEQRVL444 heptad. We assume that the deletions represent structural packages of different sizes, with the (7 + 4) deletion package possibly representing a minimal structural and functional unit around the 438ELEQRVL444 heptad.

So far, the sequences that were removed were uninterrupted. Next, we deleted 14 or 7 residue segments, i.e. 431ALENTNR ELEQRVL444 and 438ELEQRVL444 and the distal 452QEKE455 motif, thus retaining the intervening heptad 445ERTAALL451 (Fig. 5). Both chimeras were well expressed, had comparable AC activities, and were stimulated by serine in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5). The construct with (-14 −4) = −18 residues was activated 53%, and the EC50 for serine was 20 μm. The construct with (-7–4) = −11 residues was stimulated 35% above basal activity, and the EC50 was 12 μm serine (Fig. 5). Respective controls with 10 mm aspartate ascertained specificity (Fig. 5). As a further control, we deleted the stretches of seven (ELEQRVL) or 14 residues (ALENTNRELEQRVL) alone; i.e. we retained the QEKE. These constructs were expressed as active, membrane-bound ACs, yet serine did not regulate (Fig. 5). Thus, for serine regulation and signal reversion, the removal of at least one heptad, minimally ELEQRVL, plus a four-residue stutter, was indispensible, but the deletion must not be continuous.

Because we lack structural information of the ensemble, we can only speculate that we are dealing with a highly ordered microdomain within the S-helix that operates as a signal processing unit or perhaps as a reversion module. It can either block signaling, i.e. no serine response, or determine the outcome of the cytoplasmic receptor response, depending on as yet unknown intrinsic structural and functional transitions. If such a rather general hypothesis is relevant, we should be able to affect signaling not only by removing the module but also by inserting it between the CyaG HAMP transducer and the AC output domain. Accordingly, we generated constructs in which we inserted the above functionally established 11-, 18-, and 25-amino acid units as elongations after the 452QEKE455 motif into the linker (Fig. 6). The length of the S-helix between HAMP and AC domains was thus artificially extended to 36, 43, and 50 residues, respectively. The chimeras were expressed, had comparable AC activities, and were specifically stimulated by serine and not by aspartate (Fig. 6). Thus, we identified yet another modality of signal reversion. The distinct differences in stimulations described above were carried over in the elongation experiments. Maximal stimulations by serine were 45, 150, and 60% for the 11, 18, and 25 residue insertions, respectively. The corresponding EC50 concentrations were 740, 80, and 59 μm. Thus, the pattern of stimulation mirrored the observations made with the corresponding deletions (compare Fig. 6 with Figs. 2–4). The data bolster the proposal that the S-helix in CyaG is an independent signal processing unit, possibly a reversion unit, that processes an external signal that passes across the membrane and through the HAMP domain on its way to the output AC domain.

Next, we asked whether these biochemical effects would translate into an in vivo function determined by induction of β-galactosidase expression via stimulation of AC activity by serine. E. coli cya cultures were transformed with chimera C of Fig. 6, in which 438ELEQRVLERTAALLQEKE455 was inserted after the QEKE motif between the linker and the AC output domain and grown for 90 min in the presence of different serine concentrations (and 3 mm aspartate as a control). After cell lysis, β-galactosidase activity was determined spectrophotometrically (Fig. 7). β-Galactosidase expression was enhanced in a serine concentration-dependent manner. With about 150 μm serine, the EC50 concentration was close to that observed in vitro (compare with Fig. 6C). The data demonstrated that 1) the “reversion module” that we attached in vitro retains its functionality in vivo, arguing that we characterized a functional module involved in signaling and 2) that the in vitro and in vivo sensitivities for the serine ligand are of the same order of magnitude.

In an extension of the above experiments, we inserted one and two additional units of 18 residues each (438E-455E) into the latter construct, thus increasing the length of the linker to 61 and 79 residues, respectively. The hypothesis was that each additional reversion module should affect the cytoplasmic signal (Fig. 8). Both chimeras were expressed as membrane-bound proteins and had robust AC activity. The extensions of the linker from 25 to up to 79 residues did not result in uncontrolled or uncontrollable activity states of CyaG (Fig. 8). Activity was controlled because AC activity of the catalytic domains alone can reach up to 1 μmol cAMP/mg × min (11). With the extension by 36 residues (2 × 18), serine regulation was not observed (Fig. 8). However, with the 54-residue extension (3 × 18), serine activated by 71%, and the EC50 for serine was 48 μm (Fig. 8). Because the efficacy of activation observed in the construct extended by 54 residues was diminished compared with that with an 18-residue extension (compare Figs. 6 and 8), it is conceivable that the expected inhibition with a 36-residue extension was too small to be detectable. In line with this argument is the observation that signaling through the 3-fold extended linker appeared to be attenuated by the added distance between the HAMP and AC domains. Nevertheless, the core of the signal processing units remained structurally and functionally intact.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we established that in a chimera composed of the serine receptor of the E. coli Tsr chemotaxis protein and the CyaG AC from A. maxima, the S-helix located between the HAMP signal transducer and the cyclase output domain is critical for enzyme regulation. The S-helix had been identified in a comprehensive bioinformatics study to connect a multitude of upstream sensory domains with downstream catalytic domains (1). It spans a stretch of up to 50 residues and has been modeled as a parallel coiled coil of two parallel α-helices involving a total of seven characteristic heptad units (abcdefg)7 in which the first (a) and fourth (d) positions are hydrophobic residues (1). The N- and C-terminal boundaries of the S-helix are not clearly demarcated. As demonstrated with chimeras composed of the Tsr serine receptor and components of the Rv3645 AC, which does not contain an S-helix-like linker, it is neither essential for downstream dimerization of catalytic AC monomers nor for AC regulation (11, 16).

A comparison of the linkers between the HAMP and catalytic domains of the bacterial ACs Rv3645 from M. tuberculosis and CyaG from A. maxima revealed the presence of an S-helix in CyaG. The linker in CyaG is 25 residues longer than that in Rv3645. It contains signature sequences characteristic for the S-helix (1). Surprisingly, removal of 25 but not 26 residues from the CyaG linker resulted in signal reversion of Tsr receptor stimulation, indicating that length, likely the proper helical register, is important for communicating the serine signal (Fig. 2). To decipher which segment of the 25-residue sequence might cause signal reversion, we generated nine deletion mutants in a heptad scan starting at the N-terminal 426RDSFIAL432 to the C-terminal 449ALLQEKE455, similar to those described for NarX (supplemental Fig. 2S (32). None of the mutants was significantly regulated by serine (supplemental Fig. 2S). Following earlier studies with NarX (32), we also made deletions of four residue sequences in what we speculated to constitute stutters (439LEQR442 and 452QEKE455). Again, regulation by serine was abrogated (supplemental Fig. 2S).

We noted a considerable degree of variability in basal AC activity in various chimeras. The mean basal activity in constructs in which serine receptor stimulation was inhibitory was 14.9 ± 3.1 nmol cAMP/mg/min (n = 4), whereas basal activity in chimeras that were activated by serine was 6.4 ± 1.9 nmol cAMP/mg/min (n = 11). This difference was not statistically significant (p < 0.07). Nevertheless, this may indicate that AC activity in inhibited chimeras was less restrained compared with activated chimeras. In addition, slight and unavoidable variations in the rates of expression and preparation and purification of bacterial membranes may have contributed to these variations. Unregulated chimeras had basal AC activities in between (11.4 ± 2.7 nmol cAMP/mg/min, n = 13). The interpretation of the data is not affected by those differences in basal activities, as each construct serves as its own control, i.e. basal versus stimulated. In fact, all stimulations and inhibitions by 10 mm serine shown in Figs. 1–8 were statistically significant (p < 0.5). The EC50 concentrations for serine were mostly between 6 and 70 μm except for those constructs in which the S-helix was extended. Probably the extensions resulted in the requirement of higher receptor occupancy to initiate the necessary conformational processes.

Removal of 25 residues formally corresponded to deletion of three heptads and a stutter. When the initial 25 residue deletion was curtailed by one or two heptads, signal reversion was observed, provided the deletion was properly placed (Figs. 3 and 4). The deletion of 11 residues, i.e. one heptad and a stutter, turned out to be the minimal requirement for signal reversion. Taken together, the data indicated that signal reversion generally required deletion of one to three heptads plus a stutter. The data are compatible with the notion that removal of distinct structural elements rather than sequence is the key feature. The surprising observation that the deletion must not necessarily be continuous (Fig. 5) underscores this statement. Obviously, within the designated S-helix, distinct structural elements exist that interact over a distance, and the output signal is reverted when a minimal, structurally interacting unit is deleted. The property of an independent signal-modifying module is underscored by the fact that we could re-engineer the chimera by insertion of additional “units.” Duplication (3 × 7 + 4) or insertion of 18 (2 × 7 + 4) or 11 (7 + 4) residues of the S-helix also resulted in signal reversion; i.e. we were able to insert three different modules, each of which switched the serine signal from inhibition to activation. The structure of such a unit module remains to be elucidated.

In the chimera under study, the membrane anchor of CyaG, which has two transmembrane spans, was replaced by the serine receptor from Tsr. The other components were from CyaG. CyaG is a class IIIa cyclase closely related to mammalian ACs that, like the Tsr receptor, requires dimerization for activity (38). Control of AC dimerization is a potential mechanism of output regulation, as suggested earlier for a retinal guanylyl cyclase (see below). Upon binding of serine to the periplasmic receptor, the signal is transmitted through the membrane to the cytoplasmic HAMP domain. Although individual structures of class III AC dimers and HAMP domains are available, a structure of a HAMP domain in concert with its AC output domain has yet to be elucidated (18–19, 45–46). The structure of a HAMP is a dimeric, four-bundle, parallel coiled coil (18–19). Currently, different models are discussed of how the HAMP domain as the immediate receiver of the transmembrane signal processes and propagates the signal to the downstream output domain (18, 20, 30). The S-helix in CyaG is located C-terminally from the HAMP, and a critical question is how conformational changes of HAMP are transmitted to and through the S-helix to the AC. It is reasonable to assume that the C-terminal AS2 helix of HAMP is continuous with the projected α-helix of the S-helix. The structure of a poorly conserved S-helix from a soluble rat guanylyl cyclase (sGCβ1) is available (47). However, in the absence of upstream and downstream signaling domains, questions with respect to the mechanism of signaling cannot be discussed. The structure supports the suggestion that HAMP and S-helix can “melt” and create a fluent transition between each other (1). Thus, the S-helix serves as the immediate receiver of the HAMP signal and propagates and modulates the structural changes in the direction of the output domain. Therefore, the two-helical coiled coil S-helix probably has a high intrinsic flexibility because a rigid coiled coil would thwart signal transduction (1). One may predict that it is rather metastabile when considering the long-distance propagation of conformational changes that are caused by the free energy derived from serine binding to the periplasmic receptor. It was suggested that the S-helix is involved in dimerization and operates as a switch that prevents constitutive activation of downstream signaling domains in the absence of stimulation of an upstream sensory domain (1, 48). Our data highlight another, completely unsuspected function of the S-helix. It operates as an autonomous module within the intramolecular signaling cascade and may well fold independently from HAMP, as it is functionally equivalent to the upstream domain. An important question is whether such regulatory capabilities are used in bacteria. S-helices have different lengths in various contexts (1). For example, a His-kinase from Beggiatoa has an S-helix with an internal repeat of 18 residues comprising and, thus, doubling a conserved ERT motif (see below). This might indicate that in Beggiatoa, the signal of the His-kinase is reversed. Variations in the length of the S-helix may allow formation of structures tailored to particular up- and downstream signaling needs. Further, this may enable modulation of S-helix functions via secondary modifications or via binding proteins such as the retinal guanylyl cyclase binding protein GCAP-1 (48).

A highly conserved ERT motif in the S-helix has been considered to form a distinctive structural feature that functions as a switch (1). Its mutation in an S-helix in human retinal guanylyl cyclases causes various retinal disorders and ensuing blindness, such as autosomal dominant cone-rod dystrophy (48–50). The effects of the mutations that are mediated via the Ca2+-binding protein GCAP-1 result in abnormally high enzyme activity (48). Qualitatively similar effects have been reported for the yeast Sln1p kinase (51). Our experiments demonstrate that for switching the signal, the presence of the ERT motif is irrelevant, as deletion of the ERT motif is not a precondition for signal reversion. However, an R446A point mutant in the Tsr-CyaG parent chimera abrogated serine regulation and impaired AC activity (data not shown). Thus, the ERT motif clearly has a distinct role in maintaining important structural and functional features of the S-helix, yet the absence of this motif in the context investigated here has no detrimental effects; i.e. the ERT motif is not invariably connected to the switch unit needed for signal reversion. We were unable to pinpoint a stutter sequence in the S-helix of CyaG. For signal reversion, minimally, the deletion of the heptad 438ELEQRVL444 together with a variable stutter was essential. E.g., the deletion of 438ELEQRVL-ERTA448 resulted in 84% stimulation by serine, and the deletion of the separated sequences 438ELEQRVL444 and 452QEKE455 resulted in 35% activation. Without removal of the ELEQRVL residues plus a stutter, we did not observe regulation/stimulation in any chimera. This may indicate that 1) the heptad ELEQRVL has a central structural function; 2) several segments of the S-helix can supply a stutter function, something akin to a floating stutter; 3) currently, heptads in the S-helix of CyaG cannot be assigned unambiguously because of an apparently delocalized stutter; and 4) the S-helix is composed of several interacting structural units that bestow a high degree of flexibility.

How is the serine signal transmitted from the HAMP domain through the S-helix to the AC? Details of the conformational changes necessary for regulation of the dimeric AC output domain must be elucidated. As pointed out, it is likely that the S-helix as a module is rather metastabile and that signaling could well involve reversible low-energy order-disorder transitions that would allow the output domain to assemble according to the affinity of the monomers. In addition, it will be interesting to see which domain movements are required for signal reversion from cyclase inhibition to cyclase activation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. R. Lukowski for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 766.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1S and 2S.

- HAMP

- histidine kinase, adenylyl cyclase, methyl-accepting proteins of chemotaxis, protein-phosphatases

- AC

- adenylyl cyclase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anantharaman V., Balaji S., Aravind L. (2006) The signaling helix: A common functional theme in diverse signaling proteins. Biol. Direct 1, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wuichet K., Cantwell B. J., Zhulin I. B. (2010) Evolution and phyletic distribution of two-component signal transduction systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 219–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galperin M. Y. (2004) Bacterial signal transduction network in a genomic perspective. Environ. Microbiol. 6, 552–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Galperin M. Y., Gomelsky M. (2005) Bacterial signal transduction modules: From genomics to biology. ASM News 71, 326–333 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parkinson J. S. (1993) Signal transduction schemes of bacteria. Cell 73, 857–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stock J. B., Ninfa A. J., Stock A. M. (1989) Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53, 450–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stock A. M., Mottonen J. M., Stock J. B., Schutt C. E. (1989) Three-dimensional structure of CheY, the response regulator of bacterial chemotaxis. Nature 337, 745–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ulrich L. E., Koonin E. V., Zhulin I. B. (2005) One-component systems dominate signal transduction in prokaryotes. Trends Microbiol. 13, 52–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhulin I. B., Nikolskaya A. N., Galperin M. Y. (2003) Common extracellular sensory domains in transmembrane receptors for diverse signal transduction pathways in bacteria and archaea. J. Bacteriol. 185, 285–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parkinson J. S., Kofoid E. C. (1992) Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 26, 71–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanchan K., Linder J., Winkler K., Hantke K., Schultz A., Schultz J. E. (2010) Transmembrane signaling in chimeras of the Escherichia coli aspartate and serine chemotaxis receptors and bacterial class III adenylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2090–2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ward S. M., Bormans A. F., Manson M. D. (2006) Mutationally altered signal output in the Nart (NarX-Tar) hybrid chemoreceptor. J. Bacteriol. 188, 3944–3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baumgartner J. W., Kim C., Brissette R. E., Inouye M., Park C., Hazelbauer G. L. (1994) Transmembrane signalling by a hybrid protein. Communication from the domain of chemoreceptor Trg that recognizes sugar-binding proteins to the kinase/phosphatase domain of osmosensor EnvZ. J. Bacteriol. 176, 1157–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin T., Inouye M. (1994) Transmembrane signaling. Mutational analysis of the cytoplasmic linker region of Taz1–1, a Tar-EnvZ chimeric receptor in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 244, 477–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Utsumi R., Brissette R. E., Rampersaud A., Forst S. A., Oosawa K., Inouye M. (1989) Activation of bacterial porin gene expression by a chimeric signal transducer in response to aspartate. Science 245, 1246–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mondéjar L. G., Lupas A., Schultz A., Schultz J. E. (2012) HAMP domain-mediated signal transduction probed with a mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase as a reporter. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1022–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aravind L., Ponting C. P. (1999) The cytoplasmic helical linker domain of receptor histidine kinase and methyl-accepting proteins is common to many prokaryotic signalling proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176, 111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hulko M., Berndt F., Gruber M., Linder J. U., Truffault V., Schultz A., Martin J., Schultz J. E., Lupas A. N., Coles M. (2006) The HAMP domain structure implies helix rotation in transmembrane signaling. Cell 126, 929–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Airola M. V., Watts K. J., Bilwes A. M., Crane B. R. (2010) Structure of concatenated HAMP domains provides a mechanism for signal transduction. Structure 18, 436–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferris H. U., Dunin-Horkawicz S., Mondéjar L. G., Hulko M., Hantke K., Martin J., Schultz J. E., Zeth K., Lupas A. N., Coles M. (2011) The mechanisms of HAMP-mediated signaling in transmembrane receptors. Structure 19, 378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Milburn M. V., Privé G. G., Milligan D. L., Scott W. G., Yeh J., Jancarik J., Koshland D. E., Jr., Kim S. H. (1991) Three-dimensional structures of the ligand-binding domain of the bacterial aspartate receptor with and without a ligand. Science 254, 1342–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scott W. G., Milligan D. L., Milburn M. V., Privé G. G., Yeh J., Koshland D. E., Jr., Kim S. H. (1993) Refined structures of the ligand-binding domain of the aspartate receptor from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 232, 555–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang Y., Park H., Inouye M. (1993) Ligand binding induces an asymmetrical transmembrane signal through a receptor dimer. J. Mol. Biol. 232, 493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ames P., Zhou Q., Parkinson J. S. (2008) Mutational analysis of the connector segment in the HAMP domain of Tsr, the Escherichia coli serine chemoreceptor. J. Bacteriol. 190, 6676–6685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mowbray S. L., Koshland D. E., Jr. (1990) Mutations in the aspartate receptor of Escherichia coli which affect aspartate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 15638–15643 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gardina P. J., Manson M. D. (1996) Attractant signaling by an aspartate chemoreceptor dimer with a single cytoplasmic domain. Science 274, 425–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chervitz S. A., Falke J. J. (1996) Molecular mechanism of transmembrane signaling by the aspartate receptor. A model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2545–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim K. K., Yokota H., Kim S. H. (1999) Four-helical-bundle structure of the cytoplasmic domain of a serine chemotaxis receptor. Nature 400, 787–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kitanovic S., Ames P., Parkinson J. S. (2011) Mutational analysis of the control cable that mediates transmembrane signaling in the Escherichia coli serine chemoreceptor. J. Bacteriol. 193, 5062–5072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou Q., Ames P., Parkinson J. S. (2009) Mutational analyses of HAMP helices suggest a dynamic bundle model of input-output signalling in chemoreceptors. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 801–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wright G. A., Crowder R. L., Draheim R. R., Manson M. D. (2011) Mutational analysis of the transmembrane helix 2-HAMP domain connection in the Escherichia coli aspartate chemoreceptor tar. J. Bacteriol. 193, 82–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stewart V., Chen L. L. (2010) The S helix mediates signal transmission as a HAMP domain coiled-coil extension in the NarX nitrate sensor from Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 192, 734–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Navarro M. V., Newell P. D., Krasteva P. V., Chatterjee D., Madden D. R., O'Toole G. A., Sondermann H. (2011) Structural basis for c-di-GMP-mediated inside-out signaling controlling periplasmic proteolysis. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newell P. D., Boyd C. D., Sondermann H., O'Toole G. A. (2011) A c-di-GMP effector system controls cell adhesion by inside-out signaling and surface protein cleavage. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salomon Y., Londos C., Rodbell M. (1974) A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal. Biochem. 58, 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mesibov R., Adler J. (1972) Chemotaxis toward amino acids in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 112, 315–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller J. H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38. Linder J. U., Schultz J. E. (2003) The class III adenylyl cyclases. Multi-purpose signalling modules. Cell. Signal. 15, 1081–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Galperin M. Y. (2010) Diversity of structure and function of response regulator output domains. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 150–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hazelbauer G. L., Falke J. J., Parkinson J. S. (2008) Bacterial chemoreceptors. High-performance signaling in networked arrays. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 9–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Biegert A., Mayer C., Remmert M., Söding J., Lupas A. N. (2006) The MPI bioinformatics toolkit for protein sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W335–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gruber M., Lupas A. N. (2003) Historical review. Another 50th anniversary. New periodicities in coiled coils. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 679–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lupas A. N., Gruber M. (2005) The structure of α-helical coiled coils. Adv. Protein Chem. 70, 37–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Appleman J. A., Stewart V. (2003) Mutational analysis of a conserved signal-transducing element. The HAMP linker of the Escherichia coli nitrate sensor NarX. J. Bacteriol. 185, 89–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tews I., Findeisen F., Sinning I., Schultz A., Schultz J. E., Linder J. U. (2005) The structure of a pH-sensing mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase holoenzyme. Science 308, 1020–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sinha S. C., Wetterer M., Sprang S. R., Schultz J. E., Linder J. U. (2005) Origin of asymmetry in adenylyl cyclases. Structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv1900c. EMBO J. 24, 663–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ma X., Beuve A., van den Akker F. (2010) Crystal structure of the signaling helix coiled-coil domain of the β1 subunit of the soluble guanylyl cyclase. BMC Struct. Biol. 10, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ramamurthy V., Tucker C., Wilkie S. E., Daggett V., Hunt D. M., Hurley J. B. (2001) Interactions within the coiled-coil domain of RetGC-1 guanylyl cyclase are optimized for regulation rather than for high affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26218–26229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kelsell R. E., Gregory-Evans K., Payne A. M., Perrault I., Kaplan J., Yang R. B., Garbers D. L., Bird A. C., Moore A. T., Hunt D. M. (1998) Mutations in the retinal guanylate cyclase (RETGC-1) gene in dominant cone-rod dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 1179–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gregory-Evans K., Kelsell R. E., Gregory-Evans C. Y., Downes S. M., Fitzke F. W., Holder G. E., Simunovic M., Mollon J. D., Taylor R., Hunt D. M., Bird A. C., Moore A. T. (2000) Autosomal dominant cone-rod retinal dystrophy (CORD6) from heterozygous mutation of GUCY2D, which encodes retinal guanylate cyclase. Ophthalmology 107, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tao W., Malone C. L., Ault A. D., Deschenes R. J., Fassler J. S. (2002) A cytoplasmic coiled-coil domain is required for histidine kinase activity of the yeast osmosensor, SLN1. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 459–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.