Abstract

Although gibberellins (GAs) are well known for their growth control function, little is known about their effects on primary metabolism. Here the modulation of gene expression and metabolic adjustment in response to changes in plant (Arabidopsis thaliana) growth imposed on varying the gibberellin regime were evaluated. Polysomal mRNA populations were profiled following treatment of plants with paclobutrazol (PAC), an inhibitor of GA biosynthesis, and gibberellic acid (GA3) to monitor translational regulation of mRNAs globally. Gibberellin levels did not affect levels of carbohydrates in plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. However, the tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates malate and fumarate, two alternative carbon storage molecules, accumulated upon PAC treatment. Moreover, an increase in nitrate and in the levels of the amino acids was observed in plants grown under a low GA regime. Only minor changes in amino acid levels were detected in plants treated with GA3 alone, or PAC plus GA3. Comparison of the molecular changes at the transcript and metabolite levels demonstrated that a low GA level mainly affects growth by uncoupling growth from carbon availability. These observations, together with the translatome changes, reveal an interaction between energy metabolism and GA-mediated control of growth to coordinate cell wall extension, secondary metabolism, and lipid metabolism.

Keywords: Gibberellin, growth, paclobutrazol, primary metabolism, translatome

Introduction

Gibberellins (GAs) are tetracyclic diterpenoid plant growth hormones involved in the regulation of diverse physiological processes including seed germination, stem elongation, leaf expansion, root growth, and the development of reproductive organs (Olszewski et al., 2002; Hedden, 2003; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007; Schwechheimer and Willige, 2009). Mutants deficient in GA synthesis or signalling have germination deficiencies, remain dwarfed, and typically exhibit delayed flowering phenotypes. The metabolic pathways of GA biosynthesis and degradation, as well as elements of GA signalling pathways, have been reported (reviewed in Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Olszewski et al., 2002; Yamaguchi, 2008). Terpene cyclases convert geranylgeranyl diphosphate to ent-kaurene which is then further channelled into ent-kaurenoic acid and GA12 by ent-kaurene oxidase (KO) and ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase (KAO), respectively (Sun and Kamiya, 1997; Helliwell et al., 2001; Yamaguchi, 2008). Restricting KO activity in mutants limits GA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Helliwell et al., 1998). Similarly, inhibiting KO by the chemical paclobutrazol (PAC) results in a decrease in GA content concomitant with a reduction in growth (Rademacher, 2000). The inhibitory effect of PAC can be reversed by GA application, making it a valuable tool for gaining insights into the effects of GA on plant growth and metabolism (Lenton et al., 1987; Yim et al., 1997; Rademacher, 2000; Toh et al., 2008; Filardo et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2010). In the final step of the GA biosynthetic pathway, GA12 is converted to GA4, a bioactive form, through oxidations by GA20-oxidase (GA20ox) and GA3-oxidase (GA3ox) (Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Olszewski et al., 2002). Inactivation of bioactive GA occurs through 2β-hydroxylation by GA2-oxidase (GA2ox). GA homeostasis is controlled by induction of GA2ox genes as well as negative feedback regulation of GA20ox and GA3ox expression by elevated levels of GA (Phillips et al., 1995; Thomas et al., 1999; Elliott et al., 2001).

Despite many reports in the literature on the roles of GAs, as yet little information is available concerning their effects on the coordination of primary metabolism and growth. Among the studies carried out to date, the overexpression of GA2ox (involved in GA catabolism) or GA20ox (involved in GA biosynthesis) induced stunted or enhanced growth, respectively, in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants (Biemelt et al., 2004). Silencing GA2ox in tobacco triggered growth and the formation of xylem fibre cells (Dayan et al., 2010). Similarly, several ‘Green Revolution’ genes responsible for dwarfing traits in crops interfere with the action of GAs (Hedden et al., 2003). In the study of Biemelt et al. (2004), vegetative growth was positively correlated with the rate of photosynthesis. In contrast, despite slow growth of GA-deficient mutants A70 and W335 of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), the rate of photosynthesis per unit leaf area was unchanged relative to that of the wild type (Nagel and Lambers, 2002). There is also conflicting evidence with respect to the effect of chemical compounds that inhibit GA biosynthesis. For example, application of the KO inhibitor PAC reduces growth in rice, but it did not affect the rate of photosynthesis (Yim et al., 1997). Uniconazole is another plant growth retardant which primarily acts by inhibiting KO (Rademacher, 2000). Plants treated with uniconazole displayed growth depression, while net photosynthesis was stimulated (Thetford et al., 1995). Thus, it remains unclear how exactly GA is involved in the regulation of growth and metabolism.

Expression profiling studies have revealed many genes regulated by GA (Yamaguchi, 2008); however, in only a few cases has the physiological affect of GA on primary metabolism and its underlying genes been investigated. One example is OsPDK1 from rice, which encodes pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, a negative regulator of the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (mtPDC) that plays an important role in intermediary metabolism. The expression level of OsPDK1 increased after gibberellic acid (GA3) treatment, resulting in lowered pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. Blocking PDK1 expression in transgenic rice by RNA interference reduced vegetative growth compared with control plants, indicating that GA affects mtPDC activity by regulating the expression of OsPDK1 which then affects growth and biomass accumulation (Jan et al., 2006). This observation suggests that GA can challenge primary metabolism at the entry point of the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

The analysis of the GA signalling pathways led to the discovery of a class of negative regulators of growth called DELLA proteins, which in Arabidopsis are encoded by the genes GAI (GA Insensitive), RGA (Repressor of GA 1–3), and RGL 1–3 (RGA-like 1–3). Arabidopsis plants lacking DELLA proteins show greater root elongation and biomass accumulation under salt stress than the wild type (Achard et al., 2006), and transgenic Populus trees overexpressing Arabidopsis DELLA-domainless versions of the DELLA proteins GAI and RGL1 had profound consequences for plant morphology and cellular metabolism, suggesting increased respiration in roots and reduced carbon flux through the lignin biosynthetic pathway in shoots as well as a shift towards defence compounds associated mainly with the phenylpropanoid pathway (Busov et al., 2006). Although these studies have advanced our understanding of the effect of GAs in specific developmental phases, they provide limited information concerning the general role of GAs in the regulation of plant metabolism and growth.

Here detailed kinematic analysis of Arabidopsis plants treated with PAC and/or GA3 is combined with metabolite profiling to provide an evaluation of GA-coordinated primary plant metabolism and growth. The expression of genes regulated by GA3 in polysome-trapped RNA pools was also evaluated (as a measure of translational activity). For polysome isolation, a recently established procedure which allows efficient immunopurification of mRNAs in ribosome complexes by the use of a FLAG-tagged ribosomal protein L18 (RPL18) in Arabidopsis was used (Zanetti et al., 2005; Mustroph et al., 2009a, b). The metabolic and transcriptional/translational consequences of the altered GA levels were analysed, and the data collected are discussed in the context of current models linking plant energy metabolism to GA biosynthesis and growth. The analysis indicates that the effect of GAs on plant growth is an integral component of a large regulatory response of primary metabolism. The rise in GA level is a signal that integrates carbon metabolism and growth. However, under GA deprivation conditions, the relationships linking carbon availability and growth are modified, thus uncoupling growth from carbon availability.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Col-0 wild-type and 35S:HF-RPL18 seeds (provided by J. Bailey-Serres, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA) were sown on standard greenhouse soil (Stender AG; Schermbeck, Germany) in plastic pots with 100 ml capacity. The trays containing the pots were placed under a 16/8 h day/night or an 8/16 h day/night cycle (22/16 °C) with 60/75% relative humidity and 180 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity.

Paclobutrazol and gibberellic acid treatment

Fourteen days after sowing, plants growing singly in pots (100 ml) were watered with 10 ml of PAC solution (0.17 mM). For GA treatment, each plant was sprayed every second day with 1 ml of 50 μM GA3 containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-80. Arabidopsis plants used in the assays were placed in trays together in a random arrangement with 35 pots per tray.

Kinematic analysis

Rosette area, number of rosette leaves, and rosette fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW) were measured at 2 d intervals from 14 d to 40 d after sowing. Rosette growth was described by the sigmoidal function:

| (1) |

where A is the difference between maximal and minimal growth values, t0 is the time when growth is maximal, and b is the steepness of maximum growth.

To calculate the rosette growth rate, the differential of the sigmoidal function (1) was determined:

| (2) |

Final rosette growth was calculated as the upper asymptote (A) of the sigmoidal curve. The moment of occurrence of the limiting point in the upper threshold sector of the curve indicated the duration of rosette growth, when a rosette reached 95% of its final growth. The peak of the first derivative of the curve corresponding to the highest growth rate occurred at the zero value of the second derivative.

The relative growth rate (RGR; mg g−1 d−1) was calculated using the classical approach (Hunt, 1982):

| (3) |

where M1 and M2 are the plant mass at times t1 and t2, respectively.

Metabolite analysis

Whole rosettes were harvested successively at 15, 20, 25, or 30 d after sowing (1, 6, 11, or 16 d after onset of PAC and/or GA3 treatment), in the middle of the photoperiod. For metabolite analysis in entire plants (shoot and root), plants were harvested 27 d after sowing, when they were in the exponential growth phase. Harvests of 30 plants (six independent samples containing five whole rosettes or five root systems per samples) were performed per treatment and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Chlorophyll, sucrose, starch, total protein, total amino acid, and nitrate contents were determined as described by Cross et al. (2006). Malate and fumarate contents were determined as described by Nunes-Nesi et al. (2007). Metabolite extraction for gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was performed on the same samples as used for RNA extraction and metabolite determination by spectrophotometric methods. Derivatization and GC-MS analysis were performed as described previously in Lisec et al. (2006). NAD, NADH, NADP, and NAPH were determined following the protocol of Gibon and Larher (1997).

Measurements of photosynthetic parameters

Gas exchange measurements were performed with an open-flow gas exchange rates Li-Cor 6400 (Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) with a portable photosynthesis system to fit a whole-plant cuvette. Light was supplied from a series of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) located above the cuvette, providing an irradiance of 300 μmol m−2 s−1. The reference CO2 concentration was set at 400 μmol CO2 mol−1 air. Dark respiration was measured on whole rosettes using the same protocol on plants kept in the dark. All measurements were performed at 25 °C, and the vapour pressure deficit was maintained at 2.0±0.2 KPa, whilst the amount of blue light was set to 10% of photon flux density to optimize stomatal aperture. Fluorescence emission measurements to estimate the actual flux of photons driving photosystem II were performed using a leaf chamber fluorometer (Model 6400-40, Li-Cor). Plants 20 d after sowing were used for determination of the photosynthetic parameters.

Total and polysomal RNA isolation

Polysomes from the 35S::HF-RPL18 line (27 d after sowing, as for metabolite analyses) were immunoprecipitated using powdered tissue and extracted in polysome extraction buffer, and clarified crude extract was incubated with ANTI-FLAG-Affinity GEL (Sigma-Aldrich) as described by Mustroph et al. (2009a). RNAs of the crude extract and immunoprecipitated eluate were extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR analysis

cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of polysomal and non-polysomal RNAs using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany). Absence of genomic DNA contamination and RNA integrity were analysed as described (Piques et al., 2009). Real-time PCRs were performed in a 384-well microtitre plate with an ABI PRISM 7900 HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems Applera, Darmstadt, Germany), using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. PCRs and data analysis were performed as described (Caldana et al., 2007; Balazadeh et al., 2008). PCR primers were designed using QuantPrime (Arvidsson et al., 2008). Three biological replicates were processed for each experimental condition.

ATH1 expression profiling and data analysis

Immunopurified RNA samples from GA3- and PAC-treated plants as well as non-treated control plants (two biological replicates for each treatment) were subjected to transcriptome profiling using Affymetrix ATH1 microarrays (Atlas Biolabs; http://www.atlas-biolabs.com/). For quality check and normalization, the raw intensity values were processed with Robin software (Lohse et al., 2010) using default settings. For background correction, the robust multiarray average normalization method (Irizarry et al., 2003) was performed across all arrays. A factorial design (PAC treatment–control and GA3 treatment–control) was applied for data analysis. Statistical analysis of differential gene expression for treatment versus control samples was carried out using the linear model-based approach (Smyth, 2004). The obtained P-values were corrected for multiple testing using the nestedF procedure, applying a significance threshold of 0.05 in combination with the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) false discovery rate control. Expression data were submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE29699.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were designed in a completely randomized distribution. Analysis of variance (P < 0.05) was carried out to determine effects of treatments. Differences among means in figures and tables were examined by the Tukey or t-test. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 8.0 for Windows statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Inhibition of gibberellin biosynthesis reduces rosette expansion rate but not duration

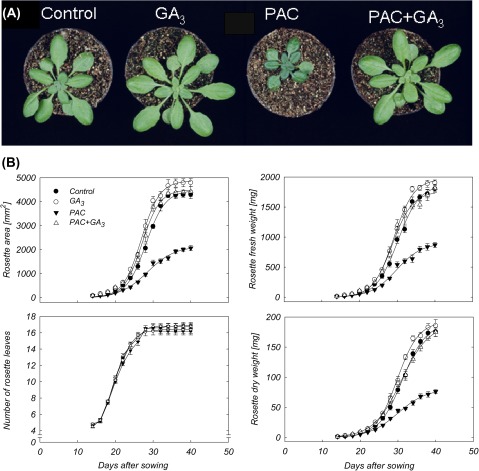

Despite the fact that many mutants with altered GA biosynthesis or signalling are known (Yamaguchi, 2008), the manipulation of GA content by PAC treatment was chosen in an attempt to monitor the translational regulation of individual mRNAs in transgenic Arabidopsis expressing a FLAG-tagged form of ribosomal protein L18. A benefit of this approach is that polysomes are purified from crude cell extracts without contamination by other mRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes (Zanetti et al., 2005); furthermore, establishing transgenic GA mutants expressing the FLAG-tagged L18 was not needed. A clear decrease of rosette area was observed for 35S::HF-RPL18 Arabidopsis plants grown under a low GA regime, namely when plants were treated with PAC and grown side by side with controls (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, application of GA3 alone caused a slight increase in the growth of the rosette as compared with control. Kinematic analysis of rosette growth revealed that FW, DW, and area of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3 follow a sigmoidal function (Fig. 1B), revealing three growth phases: an early phase during which the absolute rate of rosette growth increased, a mid phase encompassing the period of the maximum absolute rate of rosette growth, and a late phase during which the absolute rate of rosette growth decreased. PAC treatment reduced the maximal rates of rosette expansion and FW and DW accumulation by ∼60%, and rosette area and FW and DW by >50% at the end of the experiment (Table 1). However, the time at which maximal biomass accumulation occurred (on the basis of FW and DW, as well as rosette expansion) and the total duration of rosette growth were not affected by the PAC treatment (Table 1). Moreover, PAC did not affect the total number of rosette leaves (Fig. 1B). Thus, the effects of a low GA regime on the rate of expansion and on the rate of FW and DW accumulation determine to what extent the final rosette area and biomass accumulation is affected by the GA deficit. Importantly, growth inhibition induced by PAC was completely reversed by application of GA3 (Fig. 1A, B; Table 1), suggesting that the application of PAC had a specific effect on GA biosynthesis. Similar results were obtained both in the wild type (Col-0; see Supplementary Fig. S1 available at JXB online) and the transgenic 35S::HF-RPL18 line, indicating that overexpression of the FLAG-tagged RPL18 protein does not influence the response to GA3.

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic changes of 35S::HF-RPL18 Arabidopsis plants caused by treatment with PAC and/or GA3. (A) Shoots of 27-day-old plants. (B) Time course of rosette growth of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. Rosette growth was described by the sigmoidal function y = A/(1+exp {–[(x–x0)/b]}). Values are presented as means ±SE of 10 individual determinations.

Table 1.

Effect of GA regime on components of growth dynamics [final rosette area, final rosette fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW); maximal rosette expansion rate, maximal rate of FW and DW accumulation; time to maximal rosette expansion, time to maximal FW and DW accumulation; rosette expansion duration, duration of FW and DW accumulation] of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3

Comparisons were made in each column by Tukey test at the 5% level. Values are presented as means ±SE of 10 individual plants. Identical letters indicate values that are not statistically different.

| Treatment | Final rosette area (mm2) | Maximum rosette expansion rate (mm2 d−1) | Time to maximum rosette expansion (d) | Rosette expansion duration (d) |

| Control | 4473±174 a | 433±19 a | 28±2 a | 36±2 a |

| GA3 | 4871±168 a | 474±15 a | 27±1 a | 34±2 a |

| PAC | 2139±104 b | 147±8 b | 28±1 a | 37±1 a |

| PAC+GA3 | 4501±208 a | 454±23 a | 27±2 a | 34±3 a |

| Final rosette FW (mg) | Maximum rate of FW weight accumulation (mg d−1) | Time to maximum FW accumulation (d) | FW accumulation duration (d) | |

| Control | 1869±70 a | 163±10 a | 30±1 a | 39±1 a |

| GA3 | 1969±48 a | 178±5 a | 29±2 a | 37±2 a |

| PAC | 900±39 b | 67±2 b | 29±2 a | 39±1 a |

| PAC+GA3 | 1758±66 a | 160±7 a | 29±1 a | 37±1 a |

| Final rosette DW (mg) | Maximum rate of DW accumulation (mg d−1) | Time to maximum DW accumulation (d) | DW accumulation duration (d) | |

| Control | 190±8 a | 15±1 a | 31±1 a | 41±1 a |

| GA3 | 193±10 a | 17±1 a | 30±2 a | 38±2 a |

| PAC | 81±3 b | 5±1 b | 30±2 a | 41±2 a |

| PAC+GA3 | 189±7 a | 13±1 a | 31±2 a | 42±1 a |

Translatome profiling of paclobutrazol- and gibberellic acid-treated plants

Here, the immunopurification of mRNA–ribosome complexes (Mustroph et al., 2009a) was used to discover genes underlying the contrasting growth behaviour of GA3- and PAC-treated plants. Global profiling of mRNAs in ribosome complexes was done by using Affymetrix ATH1 microarrays. To this end, ribosome-associated mRNA was isolated from plants treated for 13 d with either GA3 or PAC at a final age of 27 d, corresponding to the time point of the maximal leaf expansion rate (Table 1). Analysis with the Robin software (Lohse et al., 2010) revealed that, compared with controls, 98 genes were differentially expressed by at least 2-fold after PAC treatment (39 up, 59 down), and 140 genes were differentially expressed upon GA3 treatment (138 up, two down) (Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online; see Supplementary Fig. S2). The translatome profiles revealed major changes in the expression of genes associated with the cell wall, secondary metabolism, hormone signalling, and transcription factors (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of genes affected by GA3 or PAC treatment

Expression changes are given as the log2 ratio of immunopurified polysomal mRNA from plants treated with PAC or GA3.

| AGI | Name | Log2 |

Description | |

| GA3−control | PAC−control | |||

| Cell wall | ||||

| AT1G03870 | FLA9 | 0.38 | −1.81 | Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan-protein 9 |

| AT1G10550 | XTH33 | 1.02 | −0.31 | Xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferase |

| AT1G11545 | XTH8 | 0.04 | −1.55 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 8 |

| AT1G35230 | AGP5 | 1.07 | −0.07 | Arabinogalactan-protein (AGP5). |

| AT1G69530 | EXP1 | −0.70 | −1.27 | α-Expansin gene family |

| AT2G20870 | 1.14 | −2.08 | Cell wall protein precursor | |

| AT2G40610 | EXP8 | −0.52 | −2.82 | α-Expansin gene family |

| AT2G43570 | CHI | 1.29 | 2.46 | Chitinase, putative |

| AT3G07010 | 0.07 | −1.53 | Pectin lyase-like protein | |

| AT3G10720 | 1.12 | −1.19 | Invertase/pectin methylesterase inhibitor | |

| AT3G29030 | EXP5 | 0.04 | −1.33 | α-Expansin gene family |

| AT3G44990 | XTH41 | −1.28 | 0.49 | Xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase |

| AT3G45970 | EXPL1 | 2.33 | −1.20 | Expansin-like |

| AT4G02330 | PMEPRCB | 2.26 | −0.12 | Pectinesterase activity |

| AT4G12730 | FLA2 | 0.50 | −1.56 | Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan-protein 2 |

| AT4G25810 | XTH23 | 1.09 | 0.56 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase-related protein |

| AT4G30270 | XTH24 | 1.08 | −0.48 | Xyloglucan transferase in sequence |

| AT5G49360 | BXL1 | 0.58 | −1.16 | β−D-Xylosidase/α−L-arabinofuranosidase |

| AT5G57550 | XTH25 | 1.27 | 0.15 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase-related protein |

| AT5G57560 | XTH22 | 3.46 | −1.99 | Cell wall-modifying enzyme |

| Primary metabolism | ||||

| AT1G61800 | GPT2 | 0.24 | 2.03 | Glucose6-phosphate/phosphate transporter 2 |

| AT2G43820 | SGT1 | −0.02 | 1.16 | UDP-glucose:salicylic acid glucosyltransferase |

| AT3G10720 | 1.12 | −1.17 | Plant invertase inhibitor | |

| AT3G47380 | −0.40 | −1.26 | Plant invertase inhibitor | |

| AT4G18010 | 5PTASE2 | 1.12 | 0.01 | Inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase |

| AT4G23600 | CORI3 | 0.19 | 1.23 | Encodes cystine lyase |

| AT4G33150 | LKR/SDH | 0.24 | 1.11 | Lysine-ketoglutarate reductase, lysine catabolism |

| AT5G27420 | CNI1 / ATL31 | 1.50 | −0.31 | Ubiquitin ligase that functions in the carbon/nitrogen response |

| Secondary metabolism | ||||

| AT1G02205 | CER1 | 0.52 | −1.74 | Aldehyde decarbonylase involved in wax biosynthesis |

| AT1G03495 | −0.06 | 3.02 | Acyl-transferase family protein | |

| AT1G54040 | TASTY | 0.49 | −1.23 | Epithiospecifier protein, interacts with WRKY53 |

| AT3G29590 | At5MAT | −0.12 | 1.41 | Anthocyanidin 5-O-glucoside-6''-O-malonyltransferase |

| AT3G55970 | JRG21 | −0.19 | 1.30 | Oxoglutarate/iron-dependent oxygenase |

| AT4G14090 | −0.32 | 2.54 | Anthocyanidin 5-O-glucosyltransferase | |

| AT4G22870 | 0.02 | 2.95 | 2-Oxoglutarate and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase | |

| AT4G30470 | 1.21 | −0.39 | Lignin biosynthesis | |

| AT4G34135 | 1.26 | 0.73 | Flavonol 7-O-glucosyltransferase | |

| AT4G37410 | CYP81F4 | −0.31 | 2.23 | Indole glucosinate metabolism |

| AT5G13930 | TT4 / CHS | −0.01 | 1.84 | Chalcone synthase |

| AT5G17050 | −0.02 | 1.08 | Anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase | |

| AT5G17220 | TT19 | −0.28 | 2.75 | Glutathione transferase |

| AT5G42800 | TT3 | 0.17 | 2.87 | Dihydroflavonol reductase |

| AT5G54060 | UF3GT | −0.04 | 2.15 | UDP-glucose:flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase |

| Lipid metabolism | ||||

| AT1G06080 | ADS1 | 0.65 | −1.67 | Δ9-Acyl-lipid desaturase |

| AT1G06350 | 0.28 | −1.86 | Fatty acid desaturase family protein | |

| AT2G38180 | −0.23 | 1.12 | SGNH hydrolase-type esterase | |

| AT2G38530 | LTP2 | −0.18 | 2.13 | Involved in lipid transfer between membranes |

| AT3G02040 | SRG3 | 1.06 | 0.24 | Senescence-related gene 3 |

| AT3G16370 | 0.10 | −1.16 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | |

| AT3G56060 | 0.51 | −2.56 | Glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase | |

| AT4G18970 | 0.15 | −2.09 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | |

| AT4G28780 | 0.21 | −1.67 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | |

| AT4G26790 | 0.09 | −1.41 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | |

| AT4G38690 | 0.48 | −1,21 | PLC-like phosphodiesterase | |

| AT4G39670 | 1.52 | 0.40 | Glycolipid transfer protein (GLTP) family protein | |

| AT5G24210 | 1.11 | −0.53 | α/α-Hydrolases superfamily protein | |

| AT5G48490 | 0.33 | −1.46 | Bifunctional inhibitor/lipid-transfer protein | |

| Hormone biosynthesis and signalling | ||||

| AT1G15550 | GA3OX1 | −0.70 | 2.32 | Gibberellic acid biosynthetic pathway |

| AT1G29440 | −0.38 | −1.30 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT1G29450 | −0.37 | −1.48 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT1G29500 | −0.33 | −2.17 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT1G29510 | SAUR68 | −0.36 | −1.49 | SAUR auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT1G30040 | GA2OX2 | 1.07 | −0.60 | Gibberellin 2-oxidase |

| AT1G72520 | LOX4 | 1.66 | 0.31 | PLAT/LH2 domain-containing lipoxygenase |

| AT2G21220 | 1.00 | −0.49 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT2G30020 | AP2C1 | 1.41 | −0.17 | PP2C-superfamily; ABA signalling |

| AT2G34600 | JAZ7 | 2.18 | 0.28 | Jasmonic-acid responsive |

| AT3G03840 | −0.31 | −1.83 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT3G25780 | AOC3 | 1.23 | 0.42 | Allene oxide cyclase; jasmonic acid biosynthesis |

| AT3G48520 | CYP94B3 | 1.26 | 0.44 | Involved in catabolism of jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine |

| AT3G53250 | 0.32 | −1.48 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT3G57530 | CPK37 | 1.40 | 0.02 | ABA signalling |

| AT4G11280 | ACS6 | 2.23 | −0.52 | 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) synthase |

| AT4G25420 | GA20OX1 | −0.65 | 1.48 | Gibberellin 20-oxidase |

| AT4G34760 | 0.23 | −1.67 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT4G38850 | SAUR15 | −0.68 | −1.52 | SAUR auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT4G38860 | −0.61 | −1.70 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | |

| AT5G07200 | GA20OX3 | −0.13 | 1.45 | Gibberellin 20-oxidase |

| AT5G51810 | GA20OX2 | −0.15 | 1.39 | Gibberellin 20-oxidase |

| AT5G45340 | CYP707A3 | 2.44 | −0.09 | ABA 8'-hydroxylase activity; ABA catabolism |

| AT5G56300 | GAMT2 | 1.09 | −0.15 | Gibberellic acid methyltransferase 2 |

| Transcription factors | ||||

| AT1G21910 | DREB26 | 2.33 | −0.32 | DREB subfamily A-5 of ERF/AP2 TF family |

| AT1G33760 | 3.03 | −0.06 | DREB subfamily A-4 of ERF/AP2 TF family | |

| AT1G50420 | SCL3 | −0.43 | 1.24 | Antagonist of DELLA proteins |

| AT1G52830 | IAA6 | 1.23 | −1.05 | IAA/AUX protein |

| AT1G53160 | SPL4 | −0.71 | 1.38 | Regulation of vegetative phase change |

| AT1G56650 | PAP1 | −0.33 | 2.19 | MYB TF involved in anthocyanin metabolism |

| AT1G66350 | RGL1 | 0.30 | −1.46 | Gibberellin signalling |

| AT1G73805 | SARD1 | 1.09 | −0.41 | Salicylic acid biosynthesis and signalling |

| AT1G77640 | 1.95 | −0.72 | DREB subfamily A-5 of ERF/AP2 TF family | |

| AT1G80840 | WRKY40 | 3.27 | 0.12 | Plant defence |

| AT2G17040 | ANAC036 | 1.73 | −0.16 | Leaf and stem morphogenesis |

| AT2G33810 | SPL3 | 0.35 | −1.46 | Regulation of vegetative phase change |

| AT2G38470 | WRKY33 | 1.83 | 0.07 | Camalexin biosynthesis; defence |

| AT2G40140 | CZF1 | 1.24 | −0.11 | Stress responsive CCCH-type zinc finger |

| AT2G46400 | WRKY46 | 1.92 | −0.47 | WRKY family Group III |

| AT3G49530 | ANAC062 | 1.33 | 0.02 | NAC domain protein involved in plant defence |

| AT3G55980 | SZF1 | 2.64 | −0.50 | Stress responsive CCCH-type zinc finger |

| AT3G58120 | bZIP61 | 0.84 | −2.75 | Encodes a member of the BZIP family |

| AT4G17490 | ERF6 | 1.39 | −0.47 | ERF subfamily B-3 of ERF/AP2 TF family |

| AT4G23810 | WRKY53 | 2.78 | −0.13 | Regulator of flowering and senescence |

| AT4G25480 | CBF3 | −1.16 | −0.89 | DREB subfamily; cold acclimation |

| AT4G31800 | WRKY18 | 2.06 | 0.46 | Development-regulated defence response |

| AT4G34410 | RRTF1 | 2.81 | −0.10 | ERF subfamily; redox homeostasis |

| AT5G04340 | ZAT6 | 1.17 | −0.15 | C2H2 zinc finger; phosphate homeostasis |

| AT5G22380 | ANAC090 | 2.20 | 0.06 | NAC domain-containing protein |

| AT5G22570 | WRKY38 | 1.94 | −0.23 | WRKY family Group III; plant defence |

| AT5G26920 | CBP60g | 1.68 | 0.31 | Salicylic acid biosynthesis and signalling |

| AT5G39860 | PRE1 | −0.75 | −2.86 | bHLH136/Paclobutrazol resistance 1 |

| AT5G49520 | WRKY48 | 1.58 | 0.41 | Stress-responsive WRKY member |

| AT5G62470 | MYB96 | 1.01 | −0.37 | R2R3 MYB involved in ABA signalling |

| AT5G67450 | AZF1 | 1.23 | −0.11 | Stress responsive zinc-finger protein |

Significance (global test; P < 0.05) is indicated in bold.

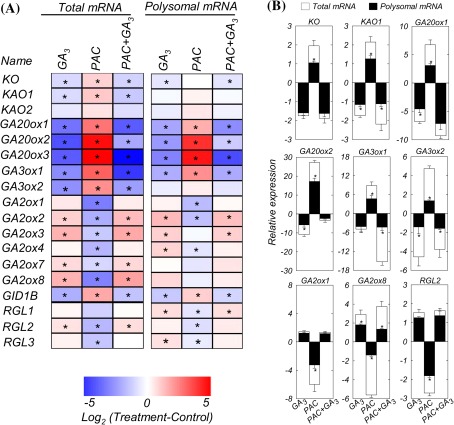

To confirm the array analysis, 18 genes representative of GA biosynthesis and signalling were selected in order to analyse their expression by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). The expression of GA-related genes measured in plants treated with PAC and/or GA3 relative to control plants (log2 ratios) is shown in Fig. 2. Relative expression values of all measurements are provided in Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online.

Fig. 2.

Changes in gene expression in shoots of Arabidopsis plants treated with PAC and/or GA3, relative to control. (A) Heat map. Different shades of red and blue express the extent of the change according to the colour bar provided (log2 ratio of control); white indicates no change. Asterisks indicate values determined by the Student’s t-test to be significantly different from the control (P < 0.05). For absolute values, see Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online. Primer sequences are given in Supplementary Table S5. (B) Relative expression of genes selected from the heat map. Data represent means ±SE of three independent replicates (each replicate is a pool of five plants). Asterisks indicate a significant difference in gene expression between non-polysomal and polysomal fractions, as determined by the Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

The expression of the GA biosynthesis genes KO, KAO1, and KAO2 is regulated in a GA-negative feedback manner (Fig. 2A, B). Overall relative expression of KO, KAO1, and KAO2 is lower at the translatome level as compared with the total mRNA level. At the translatome level, only KO showed a significant down-regulation upon GA or PAC plus GA treatment, whereas KAO1 and KAO2 expression was not affected. In addition, GA20ox1, GA20ox2, and GA20ox3 showed a similar response at the total RNA and translatome level, whereby they are down-regulated by GA3, but up-regulated by PAC, suggesting that their mRNA abundance directly influences polysome loading. For GA3ox1 and GA3ox2, the expression was down-regulated by GA3 and by PAC, although for GA3ox2 this was only observed at the total RNA level. Expression of genes for GA-inactivating enzymes (GA2ox1, GA2ox2, GA2ox3, GA2ox4, GA2ox7, and GA2ox8) was up-regulated in plants treated with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3. Moreover, GA-inactivating genes were down-regulated in PAC-treated plants (Fig. 2A, B). Only GA2ox7 and GA2ox8 did not show any response in the polysome fraction. The feedback and feedforward mechanisms also operate at the level of GA perception, with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3 negatively regulating expression of GID1B, whereas PAC treatment up-regulated GID1B (Fig. 2A) both at the total mRNA and the translated mRNA level. In contrast, RGL1, RGL2, and RGL3, encoding DELLA proteins, showed up-regulation upon GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3 treatment in both the total mRNA and polysome-associated fraction, and were down-regulated by PAC application.

Regulation of metabolism and growth processes in response to gibberellin

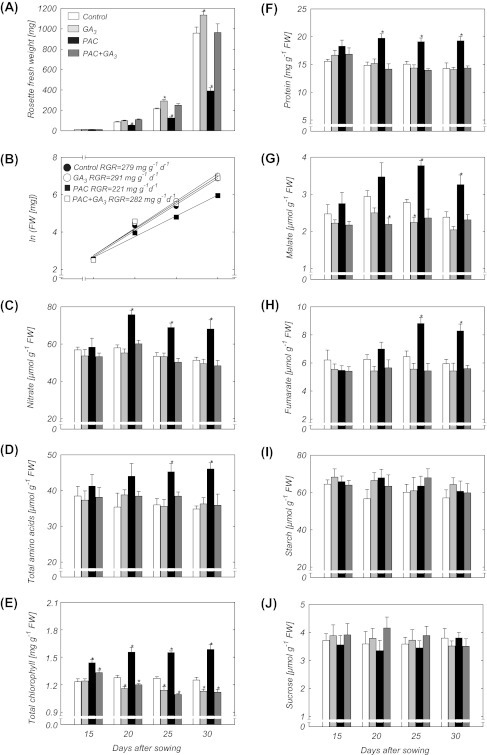

To characterize the effect of GA on primary metabolism, the levels of key primary metabolites were next monitored across the time course of shoot development. Levels of carbohydrates, organic acids, total amino acids, and nitrate, as well as chlorophyll and total protein were determined in shoots of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. Rosette FW increased with time in all treatments (Fig. 3A). However, biomass accumulation increased more slowly in PAC-treated plants than in PAC plus GA3, GA3 alone, or control treatments. Ln-transformation of these data revealed that PAC-treated plants showed a reduction of ∼20% in RGR across the entire period (15–30 d) in comparison with the other treatments (Fig. 3B). In rosette leaves from plants treated with PAC, nitrate levels increased from an initial value of 57 μmol g−1 FW at day 15 to ∼73 μmol g−1 FW at days 20–30 (Fig. 3C). However, nitrate levels remained steady in plants treated with GA3 alone, PAC plus GA3, and in controls during the course of the experiment. In addition, total amino acids in plants treated with GA3, PAC, or PAC plus GA3 initially remained at the same level as in the controls (Fig. 3D), but changed after PAC treatment at days 25–30. Furthermore, chlorophyll and total protein content were higher in plants treated with PAC than in the other treatments (Fig. 3E, F). The high levels of chlorophyll and protein in plants treated with PAC remained until the end of the experiment. In contrast, total protein contents of plants treated with GA3, or PAC plus GA3, were similar to those observed in the control plants. Moreover, total chlorophyll decreased in plants under GA3, or PAC plus GA3, treatment as compared with their respective controls 25–30 d after sowing (Fig. 3E). During rosette development, malate and fumarate levels increased significantly in PAC-treated plants at days 25–30, while they remained stable in plants exposed to GA3 and PAC plus GA3 (Fig. 3G, H). Starch and sucrose levels were similar in plants treated with PAC and/or GA3 as compared with their respective controls 15–30 d after sowing (Fig. 3I, J).

Fig. 3.

Developmental changes of biomass and major metabolites in shoots of Arabidopsis plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. (A) Rosette fresh weight. (B) Relative growth rate over vegetative development. (C) Nitrate. (D) Total amino acids. (E) Total chlorophyll. (F) Protein. (G) Malate. (H) Fumarate. (I) Starch. (J) Sucrose. Data are means ±SE of six replicates (each replicate is a pool of five plants). Asterisks indicate values determined by the Student’s t-test to be significantly different from the control (P < 0.05).

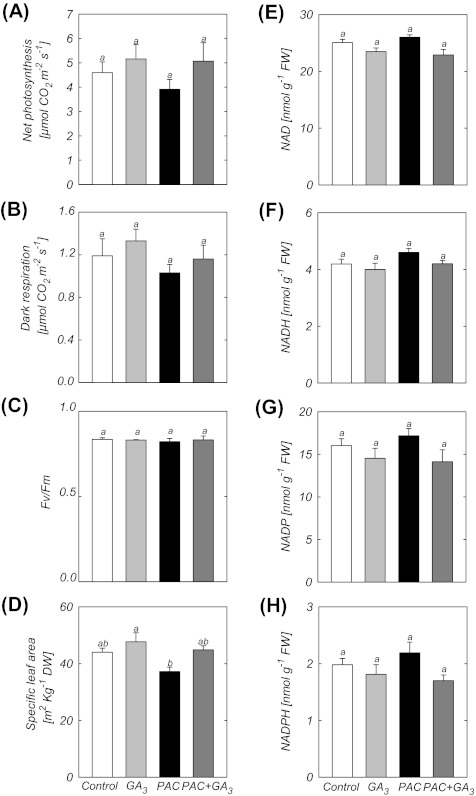

In contrast to the reduction of RGR observed in PAC-treated plants (Fig. 3B), neither the rate of net photosynthesis nor the rate of dark respiration was significantly affected by the GA regime (Fig. 4A, B). The photochemical efficiency [maximum variable fluorescence/maximum yield fluorescence (Fv/Fm)] was also not affected by PAC and/or GA3 treatment (Fig. 4C), and there was only a small decrease of specific leaf area (SLA; 15%) for whole plants treated with PAC compared with control (Fig. 4D). In agreement with the Fv/Fm, photosynthesis, and dark respiration results, no significant difference was observed in the pyridine nucleotide [NAD(P)H] levels between treatments (Fig. 4E–H). The DW/FW ratio was similar in controls and plants treated with GA3, PAC, or PAC plus GA3 (0.091, 0.086, 0.093, and 0.088, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Physiological analysis of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. (A) Rate of photosynthesis. (B) Dark respiration. (C) Fv/Fm. (D) Specific leaf area. Values are presented as means ±SE of 10 individual determinations. (E–H) NAD(P)H levels. Bars labelled with the same letter are not statistically different at the 5% level (Tukey test). Data are means ±SE of six replicates (each replicate is a pool of five plants).

Comparison of the response of the gibberellin regime to a long and short photoperiod in shoot and root

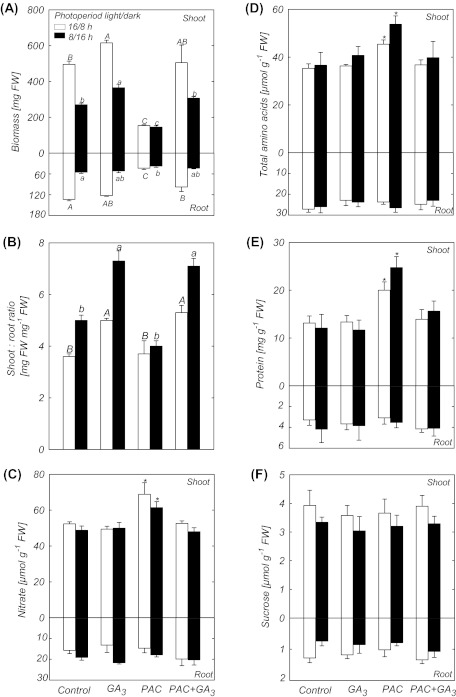

As changes in the photoperiod will alter the amount of carbon fixed each day and the carbon/nitrogen balance in plants (Stitt et al., 2010), the levels of nitrate, total amino acids, sucrose, and protein were investigated in roots and shoots of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3 to determine whether the inhibition of growth depends on the length of the photoperiod. GA3 supply increased the shoot-to-root ratio by 1.39- and 1.46-fold, in plants grown under a long or short photoperiod, respectively (Fig. 5B). The increase in the shoot-to-root ratio resulted from a stimulation of shoot growth and a slight inhibition of root growth (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, both root and shoot growth were strongly inhibited in plants growing in the environment that limited GA biosynthesis (PAC treatment), but the shoot-to-root ratio was similar to that observed in control plants under a long or short photoperiod (Fig. 5A, B). GA3 completely rescued shoot growth of PAC-treated plants, and root growth was also recovered by GA3. In roots of low GA plants, the levels of nitrate, total amino acids, protein, and sucrose were similar to those of high GA and control plants under both long- and short-day conditions (Fig. 5C–F). In contrast, nitrate, total amino acids, and protein content were increased under GA deficiency in the Arabidopsis shoots. Sucrose content (Fig. 5F) and starch levels (not shown) in shoots of low GA plants were similar to those of high GA and control plants in long- and short-day photoperiods. Thus the level of GA only affects the metabolic composition of the shoot, but not the root.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the growth response and metabolite levels in shoots and roots of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3 in long and short photoperiods. (A) Biomass. (B) Shoot-to-root ratio. (C) Nitrate. (D) Total amino acids. (E) Protein. (F) Sucrose. Bars followed by the same upper case letter (long day) or followed by the same lower case letter (short day) do not differ significantly at the 5% level (Tukey test). Asterisks indicate values determined by the Student’s t-test to be significantly different from control (P < 0.05). Values are presented as means of six replicates (each replicate is a pool of five plants) ±SE.

Changes in metabolite profiles in Arabidopsis leaves in response to gibberellin

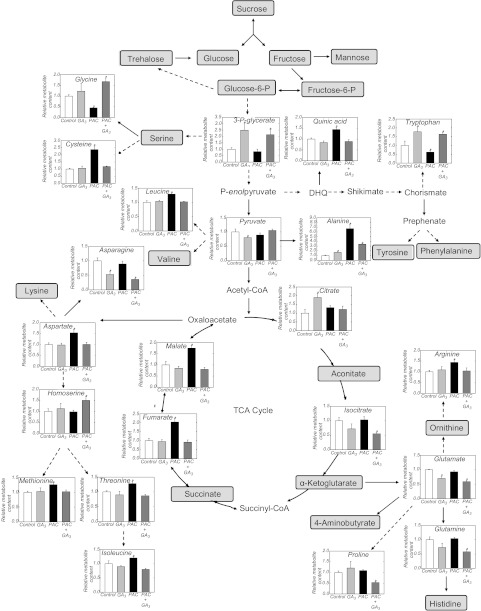

In order to verify the effect of GA on other major pathways of primary metabolism, an established GC-MS protocol was used for metabolite profiling (Fernie et al., 2004). The analysis revealed that the GA regime did not lead to significant changes in the levels of sugars such as glucose, fructose, mannose, and sucrose. Moreover, there were no significant differences in hexose-phosphates in plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. Analysis of amino acid levels revealed an increase in levels of cysteine, leucine, alanine, aspartate, methionine, threonine, isoleucine, and arginine in plants growing under a low GA regime (PAC treatment), and a decrease in glycine and tryptophan content (Fig. 6; see Supplementary Table S3 at JXB online). On the other hand, there are minor changes in amino acid levels in plants treated with GA3 alone, or PAC plus GA3. Serine content was unaltered by PAC and/or GA treatment, while the precursor, 3-P-glycerate, was higher in plants treated with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3. Glycine and cysteine are linked closely to serine formation. The reduced GA availability caused an increase (>2-fold) in cysteine. Furthermore, glycine was decreased by PAC treatment, while PAC plus GA3 increased the glycine level, and GA3 alone did not change the glycine content. PAC-treated plants showed an increase in the level of quinic acid, derivatives of which are involved in the synthesis of aromatic amino acids and secondary metabolites (Tzin and Galili, 2010). Among the aromatic amino acids tryptophan showed a clearly elevated level in plants treated with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3, while the tryptophan content was consistently reduced in plants under GA deficiency (Fig. 6). On the other hand, tyrosine and phenylalanine content remained steady across all treatments.

Fig. 6.

Changes in metabolite profiles in shoots of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. Metabolites without a significant difference between treatments are indicated by a grey square. Metabolites outside grey squares indicate that they were not measured. Continuous arrows indicate a one-step reaction, and broken arrows indicate a series of biochemical reactions. Values are presented as means of six replicates (each replicate is a pool of five plants) ±SE. Asterisks indicate values determined by the Student’s t-test to be significantly different from control (P < 0.05). DHQ, 3-dehydroquinate. A complete list of all metabolites measured by GC-MS can be found in Supplementary Table S3 at JXB online.

The level of alanine, a pyruvate-derivated amino acid, was increased >6-fold in PAC-treated plants (Fig. 6). GA3 decreased the alanine content of PAC-treated plants, while GA3 alone induced a slight increase in the alanine level. A significant increase in leucine content was only observed in PAC-treated plants, while the valine content remained at the same level in all treatments. Extending this analysis to the precursor of the amino acid family branch, only a marginal decrease of pyruvate was observed in plants treated with GA3 alone.

Significant changes of aspartate were only observed on PAC treatment (level increased by up to 54%). In plants, aspartate is also precursor of the essential amino acids asparagine, methionine, threonine, and isolecine (Jander and Joshi, 2010). PAC-treated plants showed an increase in the level of methionine, isoleucine, and threonine (Fig. 6). In contrast, methionine, isoleucine, and threonine contents in plants treated with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3 were similar to those observed in control plants. The results also showed a decrease in asparagine content of 47% and 64%, as compared with control, in plants treated with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3, respectively. On the other hand, asparagine remained at the same level in low GA plants as in the control. Plants treated with PAC and/or GA3 had no marked effect on 4-ketoglutarate levels (Fig. 6). However, there were reductions in the levels of the amino acids glutamate and glutamine only in plants treated with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3. In the present experiments, arginine accumulated only in plants grown under a low GA regime. Proline content was unaltered in plants treated with PAC or GA3 alone, but PAC plus GA3 led to a decrease of proline content.

Discussion

Gibberellin modifies translation of individual mRNAs

Cell expansion involves the selective loosening and rearrangement of the cell wall to induce turgor-driven growth (Marga et al., 2005). Expansins (Cosgrove, 2000) and xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/endohydrolases (XTHs) (van Sandt et al., 2007) are the two major protein classes known to drive this process. Treatments with GA3 or PAC have opposing effects on the expression of genes encoding these proteins, which correlates well with the observed changes in the rosette expansion rate (Table 1). At the level of primary metabolism changes were observed for several genes of cysteine, tryptophan, or lysine metabolism after PAC treatment. GA3 induced the expression of CNI1, which encodes a RING-type ubiquitin ligase (Sato et al., 2009) that associates with 14-3-3 proteins which in turn regulate carbon/nitrogen metabolism by directly binding essential enzymes involved in carbohydrate and nitrogen metabolism (Sato et al., 2011). On the other hand, genes involved in anthocyanin and flavonoid biosynthesis showed a strong up-regulation upon PAC treatment, but no effect of GA3 application on the expression of these genes was observed. Fatty acid biosynthesis in plants is adjusted to the need for membrane biogenesis during growth or repair (Ohlrogge and Jaworski, 1997). GA deprivation mainly resulted in a decrease in the expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism, while several genes showed an up-regulation after GA3 treatment, correlating with the differences in growth rate. Interestingly, the changes in GA level influence the expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis and response to the plant hormones salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid, abscisic acid (ABA), and auxin, suggesting cross-talk between these hormones and GA status. GA3 treatment results in the up-regulation of CBP60g and SARD1, two transcription regulators of SA biosynthesis and signalling (Zhang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). Furthermore, SA-responsive transcription factors belonging to the WRKY family are highly induced after GA3 treatment. Taken together, these results indicate that growth is under the direct control of GA levels.

The quantitative profiling of alterations in steady-state and polysomal mRNA populations in response to GA revealed that feedback regulation of GA biosynthesis genes and feedforward regulation of GA catabolism genes also operate at the level of the translatome (Fig. 2). On the other hand, several mRNAs encoding proteins responsible for GA biosynthesis and GA signal transduction induced at the steady-state level were modestly or strongly repressed in the polysome fractions of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3. Thus, differential mRNA translation appears to be a crucial mechanism for the control of feedback regulation of GA-related genes and thus biomass accumulation.

Changes in growth and primary metabolism are interlinked with gibberellin level

In an attempt to clarify the effect of GA on primary metabolism and growth, the major carbon metabolites as well as nitrate, chlorophyll, and total protein were determined across plant development. The increase in nitrogen content in shoots of PAC-treated plants was accompanied by an increase in total protein and chlorophyll (Fig. 3). Since leaf expansion was impaired by the low GA regime, the accumulation of protein and chlorophyll in low GA plants may reflect an indirect effect of GA. However, PAC also increased the levels of protein and chlorophyll in mature leaves (see Supplementary Table S4 at JXB online), suggesting close coordination by the GA regime. The changes in nitrogen levels were also consistent with an increase in malate and fumarate concentration, which acts as a counter-anion for pH regulation during nitrate assimilation (Benzioni et al., 1971; Tschoep et al., 2009). In rosettes of plants grown under a low GA regime, a large amount of fumarate accumulated specifically 25–30 d after sowing. It is also known that fumarate serves as an alternative and flexible sink for photosynthate in Arabidopsis (Chia et al., 2000; Pracharoenwattana et al., 2010). The observation that fumarate is present at high levels in A. thaliana (Chia et al., 2000) in comparison with other plants species (Araújo et al., 2011) provides further evidence that fumarate constitutes a significant fraction of the fixed carbon in this species. In this context, fumarate accumulation in Arabidopsis shoots under low GA regimes may provide an adaptive advantage to allow rapid growth when GA becomes available. Consistent with this hypothesis, GA3 application to PAC-treated plants completely rescued their growth and concomitantly decreased the fumarate content to levels similar to those observed in control plants (see Supplementary Fig. S3 at JXB online).

Despite the fact that biomass is strongly decreased in low GA plants, a relatively small decrease in the RGR was observed. In addition, a reduced capacity for GA biosynthesis also led to a slight decrease in SLA, but did not affect photosynthesis, dark respiration, or the photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) (Fig. 4). These results provide compelling evidence that the reduced biomass was not a consequence of variation in photosynthesis or respiration rates per se. In agreement with these observations, levels of pyrimidine nucleotides [NAD(P)H] were not affected by PAC and/or GA3 treatment (Fig. 4). Leaf growth is known to be highly dependent on carbon availability (Wiese et al., 2007; Pantin et al., 2011). The low GA plants contained levels of starch and sugars similar to those of GA-treated plants (Fig. 3). However, the maximal rosette expansion rate as well as the maximal FW and DW accumulation rates were strongly affected by the low GA regime. As a consequence, the final leaf area and the final rosette FW and DW were reduced in PAC-treated plants (Table 1). Together, these data indicate that the GA level orchestrates carbon allocation and growth. Interestingly, the duration of rosette expansion and FW and DW accumulation was not affected by the GA regime. This observation suggests that the rosette expansion rate as well as the rate of FW and DW accumulation are more flexible than the duration of leaf elongation and biomass accumulation upon GA deprivation. The observed increase in nitrate, total amino acid, and protein levels in shoots of low GA plants grown under long-day conditions (Fig. 3) was also found when low GA plants were grown in an 8 h/16 h (light/dark) photoperiod, indicating a conserved effect of GA deprivation on primary metabolism. The assimilation of inorganic nitrogen into amino acids and the subsequent metabolic conversion of amino acids into protein are energetically expensive processes (Hachiya et al., 2007). Thus, the accumulation of compounds with high energy storage capacity in shoots of low GA plants can be interpreted as the result of rosette elongation being more reduced than carbon inflow, indicating an uncoupling between carbon availability and shoot elongation. In contrast to GA-deprived plants, GA3-treated plants or plants treated with PAC plus GA3 did not accumulate compounds with high energy storage capacity, showing that GA availability couples primary metabolism and growth.

In contrast to shoots, the alterations in GA level had no effect on the metabolic status of the root, which suggests that retaining compounds with high energy storage capacity in the leaves is an active process. Because nitrate levels in root remained low in all treatments, it seems unlikely that the rate of nitrogen uptake and unloading to the xylem would be affected by the GA regime in either long- or short-day conditions. Interestingly, limiting GA biosynthesis by PAC treatment led to a strong inhibition of shoot and root growth, but the shoot-to-root ratio resembled that of the control plants in long or short photoperiods. These data reflect an unaltered carbohydrate status of low GA plants as compared with control plants. In agreement with this statement, PAC treatment did not change steady-state sucrose and starch levels. Furthermore, PAC treatment did not lead to substantial changes in the levels of hexose-phosphates (Fig. 6). Taken together this indicates that the entry points of carbon into starch synthesis, glycolysis, and cell wall biosynthesis were not affected by the low GA regime. When considered alongside the observed changes in energy metabolism and growth, this strongly implies that the reduction in biomass in low GA plants originates from uncoupling energy metabolism (carbon supply) and growth (demand).

Gibberellin modulates global changes in primary metabolism

One conspicuous feature of the GA-dependent metabolite profiles was the changes in amino acids and some of their precursors (Fig. 6). The carbon backbone of glycine and cysteine is derived from serine and 3-P-glycerate. 3-P-glycerate is also an intermediate in plastidial phospholipid synthesis and forms the primary substrate for triacylglycerol synthesis (Gibon et al., 2006). It was previously shown that high 3-P-glycerate levels correlate with a high plant growth rate (Meyer et al., 2007), which is in accordance with the observation that its levels are highly induced upon GA3, and slightly reduced upon PAC treatment (Fig. 6).

The analysis of aromatic amino acids revealed that GA3 only affected the tryptophan pool. The increase of the tryptophan pool in plants treated with GA3 alone or PAC plus GA3, as well as the reduction of tryptophan level in plants treated with PAC alone indicates an effect of GA on enzyme activity or substrate availability downstream of this aromatic amino acid. Such an effect could explain certain prominent symptoms of GA availability on growth dynamics such as, for example, the dwarf shoot in low GA plants and accelerated growth following supply of GA3. Although plants have multiple pathways for indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis (Zhao, 2010), the conversion from tryptophan to either indole-3-pyruvic acid (via tryptophan transaminase and indole pyruvate decarboxylase), tryptamine (via tryptophan decarboxylase and amino oxidase), or indole-3-acetaldehyde (via indole aldehyde dehydrogenase) appears to be directly or indirectly disrupted by GA deficiency. Thus, the observed reduction in tryptophan level in low GA plants might contribute to explain the severe decrease in shoot growth in low GA plants since tryptophan deficiency has recently been associated with retardation of aerial organ development by affecting cell expansion (Jing et al., 2009). In light of this fact, GA3 was able to recover growth of plants treated with PAC and this was accompanied by an increase in tryptophan level. Furthermore, expression of various auxin-up-regulated SAUR (Small Auxin Up RNA) genes was down-regulated in rosettes of low GA plants as compared with control or GA-treated plants (Table 2). In other words, SAUR transcripts are most abundant in tissues that are elongating or programmed to elongate in response to GA, linking growth with the metabolic availability of tryptophan.

Alanine aminotransferase catalyses the interconversion of pyruvate and glutamate to 4-ketoglutarate and alanine (Rocha et al., 2010). Given that PAC reduced plant growth and increased the alanine level, it seems feasible that alanine could contribute to regulate the biosynthesis of pyruvate, facilitating the maintenance of both the carbon/nitrogen balance and the rate of respiration in the plant. In keeping with this observation, GA3 supplementation rescues shoot and root development and decreases the level of alanine in PAC-treated plants. It is well known that hypoxia alters the carbon/nitrogen balance and alanine accumulates in large amounts via an increase in alanine aminotransferase activity (Miyashita et al., 2007; Rocha et al., 2010). In the present studies, it was found that PAC treatment triggers an enhanced alanine level, and a decreased rosette growth, suggesting a modified relationship between energy metabolism and growth in low GA plants. Glutamine and glutamate serve as nitrogen transport compounds and nitrogen donors in the biosynthesis of several compounds (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2006). Nitrogen may be subsequently channelled from glutamine and glutamate to aspartate by aspartate aminotransferase, or to asparagine by asparagine synthase. As the amino acids glutamine and asparagine carry an extra nitrogen atom in the amide group of their side chains they play an important role as nitrogen carriers in cellular metabolism (Urquhart and Joy, 1981). Thus, the reduced levels of asparagine and glutamate observed in plants treated with GA3 alone and PAC plus GA3 indicate that both amino acids are being utilized more rapidly when plant growth is stimulated by the hormone. In agreement with this model, plants treated with GA3 alone and PAC plus GA3 showed a fast increase in the rate of leaf area growth and biomass accumulation. Together, these data indicate that GA is required for connecting energy metabolism and growth. Aspartate and arginine serve as important nitrogen reserves and intermediates in nitrogen recycling. These two amino acids accumulated consistently only in low GA plants. Moreover, glutamate, glutamine, and asparagine levels were not altered in low GA plants, showing the maintenance of nitrogen metabolism under GA deprivation although plant growth was decreased. Currently, metabolic profiling studies on GA-deficient mutants in Arabidopsis are scarce. However, metabolic profiling was reported for poplar overexpressing the Arabidopsis proteins GAI and RGL1 with mutated or deleted DELLA domains, respectively (Busov et al., 2006). Overexpression of the modified DELLA proteins caused accumulation of bioactive GA1 and GA4. Most of the metabolic alterations observed in the transgenic poplar leaves indicated a reduced flow of carbon through the lignin biosynthesis pathway and changes in the allocation of secondary phenolic metabolites (Busov et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, overexpression of GA20ox1 causes an enlargement of leaf size (Gonzalez et al., 2010) similar to that caused by the exogenous application of bioactive GA, but opposite to PAC treatment. As expected, the metabolite profiles of GA20ox1 overexpressors overlap only partly with those obtained here for PAC-treated plants.

In summary, metabolite analyses revealed that a low GA level mainly affects growth by uncoupling it from carbon availability. Given that under a good GA level tight relationships linking carbon availability and growth are observed, strategies to identify genes which orchestrate these relationships will probably present promising ways by which to identify new markers for growth potential.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. Phenotypic changes of Arabidopsis wild-type plants caused by PAC and/or GA3 treatment.

Figure S2. MapMan representations of differentially expressed genes.

Figure S3. Effect of treatment with PAC and/or GA3 on shoot biomass of Arabidopsis plants (27 d after sowing) and fumarate levels.

Table S1. Genes differentially expressed in GA-treated versus non-treated control plants and in PAC-treated versus non-treated controls.

Table S2. Expression of GA-related genes in plants treated with PAC and/or GA3.

Table S3. Relative metabolite content of rosettes of plants treated with PAC and/or GA3.

Table S4. Paclobutrazol increases protein and chlorophyll concentration in fully expanded leaves.

Table S5. Sequence of primers used for qRT-PCR.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Bailey-Serres (University of California, Riverside, USA) for kindly providing the 35S::HF-RPL18 seeds used in this work. We also would like to thank A. Mustroph (University of Bayreuth, Germany) for her help and advice with the immunopurification of polysomes. Furthermore, we thank K. Koehl and the Greenteam of the MPI for their assistance with plant growth. This work was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (DMR), the Max-Planck Society (WLA and ARF), and the BMBF FORSYS Systems Biology Research Initiative (GoFORSYS; BM-R; FKZ 0313924).

References

- Achard P, Cheng H, De Grauwe L, Decat J, Schoutteten H, Moritz T, Van Der Straeten D, Peng J, Harberd NP. Integration of plant responses to environmentally activated phytohormonal signals. Science. 2006;311:91–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1118642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo WL, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR. Fumarate: multiple functions of a simple metabolite. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:838–843. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson S, Kwasniewski M, Riano-Pachon DM, Mueller-Roeber B. QuantPrime—a flexible tool for reliable high-throughput primer design for quantitative PCR. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:465. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S, Riaño-Pachón DM, Mueller-Roeber B. Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biology. 2008;(Suppl. 1):63–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benzioni A, Vaadia Y, Lips SH. Nitrate uptake by roots as regulated by nitrate reduction products of shoot. Physiologia Plantarum. 1971;24:288–290. [Google Scholar]

- Biemelt S, Tschiersch H, Sonnewald U. Impact of altered gibberellin metabolism on biomass accumulation, lignin biosynthesis, and photosynthesis in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Physiology. 2004;135:254–265. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.036988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busov V, Meilan R, Rood DWP, Tschaplinski CMTJ, Strauss SH. Transgenic modification of gai or rgl1 causes dwarfing and alters gibberellins, root growth, and metabolite profiles in Populus. Planta. 2006;224:288–299. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldana C, Scheible WR, Mueller-Roeber B, Ruzicic S. A quantitative RT-PCR platform for high-throughput expression profiling of 2500 rice transcription factors. Plant Methods. 2007;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia DW, Yoder TJ, Reiter WD, Gibson SI. Fumaric acid: an overlooked form of fixed carbon in Arabidopsis and other plant species. Planta. 2000;211:743–751. doi: 10.1007/s004250000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature. 2000;407:321–326. doi: 10.1038/35030000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JM, von Korff M, Altmann T, Bartzetko L, Sulpice R, Gibon Y, Palacios N, Stitt M. Variation of enzyme activities and metabolite levels in 24 Arabidopsis accessions growing in carbon-limited conditions. Plant Physiology. 2006;142:1574–1588. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan J, Schwarzkopf M, Avni A, Aloni R. Enhancing plant growth and fiber production by silencing GA 2-oxidase. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2010;8:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RC, Smith JL, Lester DR, Reid JB. Feed-forward regulation of gibberellin deactivation in pea. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 2001;20:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fernie AR, Trethewey RN, Krotzky AJ, Willmitzer L. Metabolite profiling: from diagnostics to systems biology. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2004;5:763–769. doi: 10.1038/nrm1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo F, Robertson M, Singh DP, Parish RW, Swain SM. Functional analysis of HvSPY, a negative regulator of GA response, in barley aleurone cells and Arabidopsis. Planta. 2009;229:523–537. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0843-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Larher F. Cycling assay for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides: NaCl precipitation and ethanol solubilization of the reduced tetrazolium. Analytical Biochemistry. 1997;251:153–157. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Usadel B, Bläsing O, Kamlage K, Höhne M, Trethewey R, Stitt M. Integration of metabolite with transcript and enzyme activity profiling during diurnal cycles in Arabidopsis rosettes. Genome Biology. 2006;7:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-8-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez N, De Bodt S, Sulpice R, et al. Increased leaf size: different means to an end. Plant Physiology. 2010;153:1261–1279. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachiya T, Treashima I, Nochuchi K. Increase in respiratory cost at high temperature is attributed to high protein turnover cost in Petunia×hybrida petals. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:1269–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P. The genes of the Green Revolution. Trends in Genetics. 2003;19:5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Phillips AL. Gibberellin metabolism: new insights revealed by the genes. Trends in Plant Science. 2000;5:523–530. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01790-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell CA, Chandler PM, Poole A, Dennis ES, Peacock WJ. The CYP88A cytochrome P450, ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase, catalyzes three steps of the gibberellin biosynthesis pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2001;98:2065–2070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041588998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell CA, Sheldon CC, Olive MR, Walker AR, Zeevaart JAD, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. Cloning of the Arabidopsis ent-kaurene oxidase gene GA3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1998;95:9019–9024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R. Plant growth curves. London: E. Arnold Publishers; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan A, Nakamura H, Handa H, Ichikawa H, Matsumoto H, Komatsu S. Gibberellin regulates mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2006;47:244–253. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander G, Joshi V. Recent progress in deciphering the biosynthesis of aspartate-derived amino acids in plants. Molecular Plant. 2010;3:54–65. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y, Cui D, Bao F, Hu Z, Qin Z, Hu Y. Tryptophan deficiency affects organ growth by retarding cell expansion in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2009;57:511–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenton JR, Hedden P, Gale MD. Gibberellin insensitivity and depletion in wheat—consequences for development. In: Hoad GV, Lenton JR, Jackson MB, Atkin RK, editors. Hormone action in plant development. London: Butterworths; 1987. pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lisec J, Schauer N, Kopka J, Willmitzer L, Fernie AR. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry-based metabolite profiling in plants. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:387–396. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M, Nunes-Nesi A, Krüger P, et al. Robin, an intuitive wizard application for R-based expression microarray quality assessment and analysis. Plant Physiology. 2010;153:642–651. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.152553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QS, Paz JD, Pathmanathan A, Chiu RS, Tsai AY, Gazzarrini S. The C-terminal domain of FUSCA3 negatively regulates mRNA and protein levels, and mediates sensitivity to the hormones abscisic acid and gibberellic acid in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2010;64:100–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masclaux-Daubresse C, Reisdorf-Cren M, Pageau K, Lelandais M, Grandjean O, Kronenberger J, Valadier M-H, Feraud M, Jouglet T, Suzuki A. Glutamine synthetase–glutamate synthase pathway and glutamate dehydrogenase play distinct roles in the sink–source nitrogen cycle in tobacco. Plant Physiology. 2006;140:444–456. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.071910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marga F, Grandbois M, Cosgrove DJ, Baskin TI. Cell wall extension results in the coordinate separation of parallel microfibrils, evidence from scanning electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy. The Plant Journal. 2005;43:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RC, Steinfath M, Lisec J, et al. The metabolic signature related to high plant growth rate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2007;104:4759–4764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609709104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita Y, Dolferus R, Ismond KP, Good AG. Alanine aminotransferase catalyses the breakdown of alanine after hypoxia in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 2007;49:1108–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustroph A, Juntawong P, Bailey-Serres J. Isolation of plant polysomal mRNA by differential centrifugation and ribosome immunopurification methods. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2009a;553:109–126. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-563-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustroph A, Zanettia ME, Janga CJH, Holtanb HE, Repettib PP, Galbraithc DW, Girkea T, Bailey-Serres J. Profiling translatomes of discrete cell populations resolves altered cellular priorities during hypoxia in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2009b;106:18843–18848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel OW, Lambers H. Changes in the acquisition and partitioning of carbon and nitrogen in the gibberellin-deficient mutants A70 and W335 of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Plant, Cell and Environment. 2002;25:883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Nesi A, Carrari F, Gibon Y, Sulpice R, Lytoychenko A, Fisahn J, Graham J, Ratcliffe R, Sweetlove L, Fernie AR. Deficiency of mitochondrial fumarase activity in tomato plants impairs photosynthesis via an effect on stomatal function. The Plant Journal. 2007;50:1093–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlrogge JB, Jaworski JG. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1997;48:109–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski N, Sun TP, Gubler F. Gibberellin signaling, biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. The Plant Cell. 2002;14(Suppl.):S61–S80. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin F, Simonneau T, Rolland G, Dauzat M, Muller B. Control of leaf expansion: a developmental switch from metabolics to hydraulics. Plant Physiology. 2011;156:803–815. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AL, Ward DA, Uknes S, Appleford NE, Lange T, Huttly AK, Gaskin P, Graebe JE, Hedden P. Isolation and expression of three gibberellin 20-oxidase cDNA clones from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 1995;108:1049–1057. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piques M, Schulze WX, Hohne M, Usadel B, Gibon Y, Rohwer J, Stitt M. Ribosome and transcript copy numbers, polysome occupancy and enzyme dynamics in Arabidopsis. Molecular Systems Biology. 2009;5:314. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pracharoenwattana I, Zhou W, Keech O, Francisco PB, Udomchalothorn T, Tschoep H, Stitt M, Gibon Y, Smith SM. Arabidopsis has a cytosolic fumarase required for the massive allocation of photosynthate into fumaric acid and for rapid plant growth on high nitrogen. The Plant Journal. 2010;62:785–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher W. Growth retardants: effects on gibberellin biosynthesis and other metabolic pathways. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;51:501–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha M, Licausi F, Araújo WL, Nunes-Nesi A, Sodek L, Fernie AR, van Dongen JT. Glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle are linked by alanine aminotransferase during hypoxia induced by water logging of Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiology. 2010;152:1501–1513. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.150045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Maekawa S, Yasuda S, et al. CNI1/ATL31, a RING-type ubiquitin ligase that functions in the carbon/nitrogen response for growth phase transition in Arabidopsis seedlings. The Plant Journal. 2009;60:852–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Maekawa S, Yasuda S, Domeki Y, Sueyoshi K, Fujiwara M, Fukao Y, Goto DB, Yamaguchi J. Identification of 14-3-3 proteins as a target of ATL31 ubiquitin ligase, a regulator of the C/N response in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2011;68:137–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwechheimer C, Willige B. Shedding light on gibberellic acid signalling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2009;12:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Usadel B, Lunn J. Primary photosynthetic metabolism—more than the icing on the cake. The Plant Journal. 2010;61:1067–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP, Kamiya Y. Regulation and cellular localization of ent-kaurene synthesis. Physiologia Plantarum. 1997;101:701–708. [Google Scholar]

- Thetford M, Warren SL, Blazich FA, Thomas JF. Response of Forsythia×intermedia ‘Spectabilis’ to uniconazole. II. Leaf and stem anatomy, chlorophyll, and photosynthesis. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 1995;120:983–988. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P. Molecular cloning and functional expression of gibberellin 2-oxidases, multifunctional enzymes involved in gibberellin deactivation. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1999;96:4698–4703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh S, Imamura A, Watanabe A, et al. High temperature-induced abscisic acid biosynthesis and its role in the inhibition of gibberellin action in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiology. 2008;146:1368–1385. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschoep H, Gibon Y, Carillo P, Armengaud P, Szecowka M, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie A, Koehl K, Stitt M. Adjustment of growth and central metabolism to a mild but sustained nitrogen-limitation in Arabidopsis. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009;32:300–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzin V, Galili G. New insights into the shikimate and aromatic amino acids biosynthesis pathways in plants. Molecular Plant. 2010;3:956–972. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Nakajima M, Motoyuki A, Matsuoka M. Gibberellin receptor and its role in gibberellin signaling in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2007;58:183–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart AA, Joy KW. Use of phloem exudate technique in the study of amino acid transport in pea plants. Plant Physiology. 1981;68:750–754. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.3.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sandt VST, Suslov D, Verbelen JP, Vissenberg K. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase activity loosens a plant cell wall. Annals of Botany. 2007;100:1467–1473. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Tsuda K, Truman W, Sato M, Nguyen LV, Katagiri F, Glazebrook J. CBP60g and SARD1 play partially redundant critical roles in salicylic acid signaling. The Plant Journal. 2011;67:1029–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese A, Christ MM, Virnich O, Schurr U, Walter A. Spatiotemporal leaf growth patterns of Arabidopsis thaliana and evidence for sugar control of the diel leaf growth cycle. New Phytologist. 2007;174:752–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S. Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2008;59:225–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim KO, Kwon YW, Bayer DE. Growth responses and allocation of assimilates of rice seedlings by paclobutrazol and gibberellin treatment. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 1997;16:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti ME, Chang IF, Gong F, Galbraith DW, Bailey-Serres J. Immunopurification of polyribosomal complexes of Arabidopsis for global analysis of gene expression. Plant Physiology. 2005;138:624–635. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.059477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xu S, Ding P, et al. Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2010;107:18220–18225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005225107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2010;61:49–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.