Abstract

Aim

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a clustering of factors that are associated with increased cardiovascular risk. We aimed to investigate the proportion of patients with MetS in patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation (CR), and to describe differences between patients with MetS compared to those without MetS with regard to (1) patient characteristics including demographics, risk factors, and comorbidities, (2) risk factor management including drug treatment, and (3) control status of risk factors at entry to CR and discharge from CR.

Methods

Post-hoc analysis of data from 27,904 inpatients (Transparency Registry to Objectify Guideline-Oriented Risk Factor Management registry) that underwent a CR period of about 3 weeks were analyzed descriptively in total and compared by their MetS status.

Results

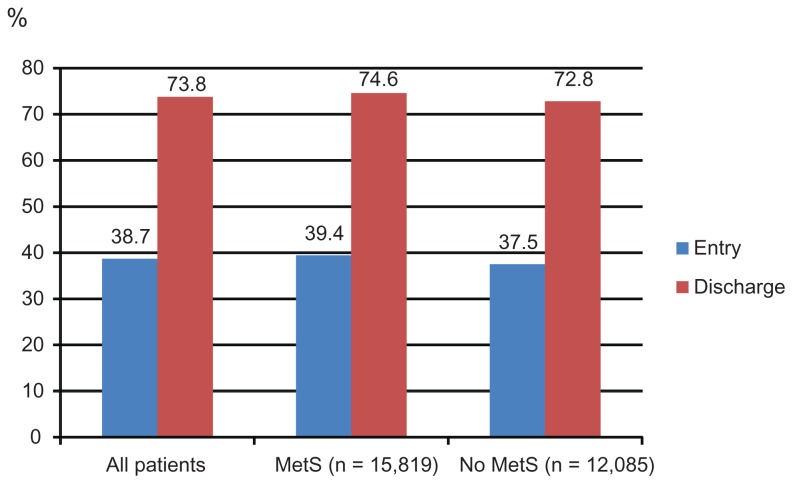

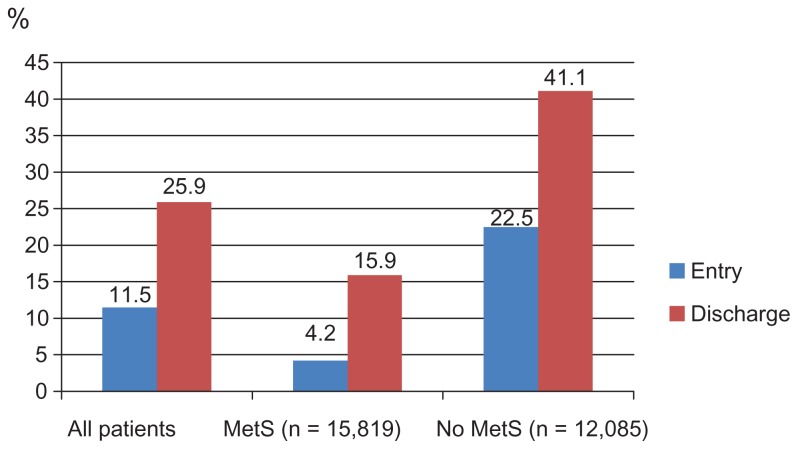

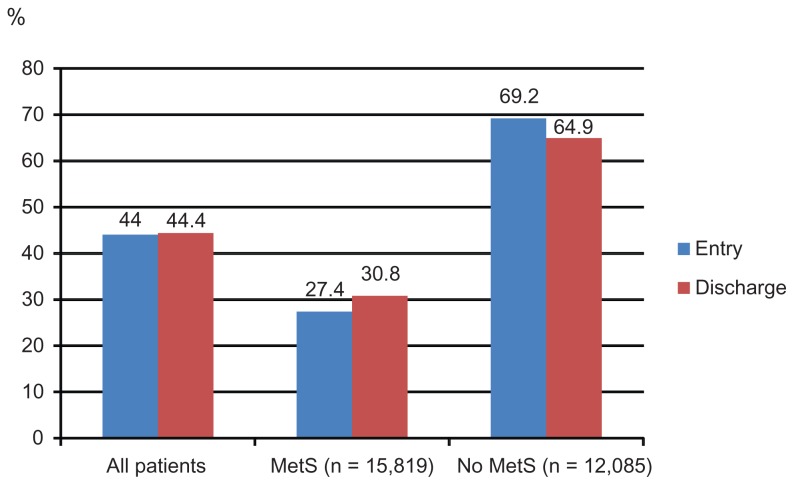

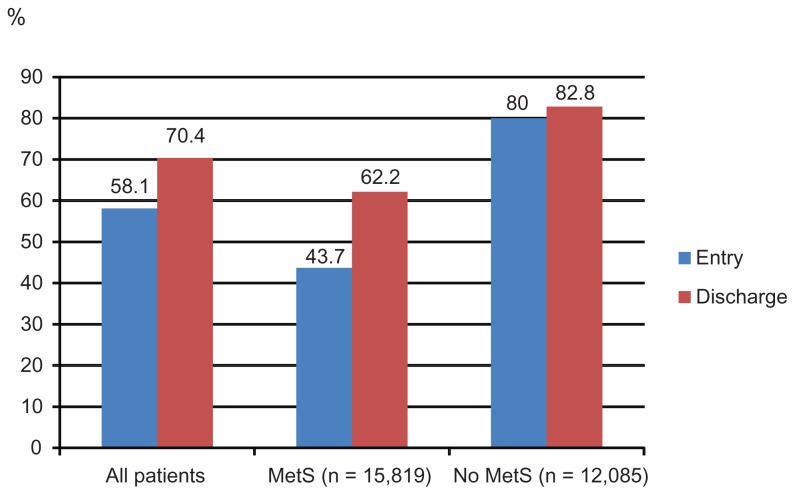

In the total cohort, mean age was 64.3 years, (71.7% male), with no major differences between groups. Patients had been referred after a ST elevation of myocardial infarction event in 41.1% of cases, non-ST elevation of myocardial infarction in 21.8%, or angina pectoris in 16.7%. They had received a percutaneous coronary intervention in 55.1% and bypass surgery (coronary artery bypass graft) in 39.5%. Patients with MetS (n = 15,819) compared to those without MetS (n = 12,085) were less frequently males, and in terms of cardiac interventions, more often received coronary artery bypass surgery. Overall, statin use increased from 79.9% at entry to 95.0% at discharge (MetS: 79.7% to 95.2%). Patients with MetS compared to those without MetS received angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, oral antidiabetics, and insulin at entry and discharge more frequently, and less frequently clopidogrel and aspirin/clopidogrel combinations. Mean blood pressure was within the normal range at discharge, and did not differ substantially between groups (124/73 versus 120/72 mmHg). Overall, between entry and discharge, levels of total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were substantially lowered, in particular in MetS patients. Thus, control rates of lipid parameters improved substantially, with the exception of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Low density lipoprotein cholesterol rates <100 mg/dL increased from 38.7% at entry to 73.8% at discharge (MetS: from 39.4% to 74.6%) and triglycerides control rates (<150 mg/dL) from 58.1% to 70.4% (MetS: 43.7% to 62.2%). Physical fitness on exercise testing improved substantially in both groups.

Conclusion

Patients with and without MetS benefited substantially from the participation in CR, as their lipid profile, blood pressure, and physical fitness improved. Treatment effects were similar in the two groups.

Keywords: cardiac rehabilitation, registry, metabolism, diabetes, dyslipidemia, control rates, risk factor, lipids

Introduction

Despite a declining incidence in recent years, cardiovascular events remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in most regions worldwide. In clinical practice, the prediction of such events to identify patients at high cardiovascular risk and to offer them preventive measures is of high priority.1 Substantial research has been performed on the clustering of cardiovascular risk factors named metabolic syndrome (MetS) and the question whether this clustering represents a disease entity in its own right. At least five definitions with slight or moderate deviations from each other have been proposed by international organizations or by expert groups.2–7 The most frequently used ones have been issued by the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP ATP) III5 and by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF).7

A setting with a known high prevalence of patients with MetS is cardiac rehabilitation (CR). CR is primarily indicated for patients who have received a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, have undergone coronary revascularization, or have chronic stable angina.8,9 The goals of CR and secondary prevention involve a program of prescribed exercise and interventions designed to modify coronary risk factors, including drug therapy. The aims are to prevent disability resulting from coronary disease, particularly in elderly persons and those with occupations that involve physical exertion, and to prevent subsequent coronary events, subsequent hospitalization, and death from cardiac causes.8 The benefits of CR are broad and compelling. Exercise together with nutritional counseling can slow the atherosclerotic process10,11 and lead to lower rates of cardiac events and hospitalizations.10,12 In a review of 22 studies, an average mortality reduction of 20% has been described for patients who underwent CR with exercise.13

In Germany, the transfer of cardiac patients from the hospital to the CR clinic is an established procedure with low barriers, and is particularly independent of socioeconomic status. Thus the situation represents not usual but rather best practice, which can be analyzed to investigate effectiveness of therapy under real practice conditions.9,14

It can be expected that a higher percentage of cardiac patients in CR fulfill the definition of MetS, but to date no specific data have been reported in this setting. The Transparency Registry to Objectify Guideline-Oriented Risk Factor Management (TROL) is one of the largest registries on CR and has been used, among others, for the description of secular trends in the management of patients in “real-world” CR.15 We performed a post-hoc analysis of data of the registry with the aim to investigate the proportion of patients with MetS in patients undergoing CR, and to describe differences between patients with MetS compared to those without MetS using the IDF definition7 with regard to (1) patient characteristics including demographics, risk factors, and comorbidities, (2) risk factor management including drug treatment, and (3) control status of risk factors at entry to CR and discharge from CR.

Methods

Source of data

TROL is a large scale prospective registry set up in 2003 under the auspices of the German Society for Prevention and Rehabilitation.16 Centers were eligible to participate if they had a significant number of CR patients, and were selected across Germany to ensure that all 16 federal states were represented adequately.15,17 Participating physicians documented inpatients on standardized case report forms. The ethics committee of the Bavarian Physician Chamber approved the study, and all patients provided informed consent. Patient data protection was ensured. We report an analysis of the dataset of the years 2005 to 2008, which comprises 27,904 patients with adequate and complete information to decide on the presence of MetS.

CR program

CR programs are not standardized in Germany in terms of type (eg, inpatient versus outpatient), length, structure, or components. However, the vast majority of patients undergo in-hospital rehabilitation therapy usually for 3–4 weeks.9 Key features of these programs are gradual increase in activity levels, continuation of risk factor modifications (eg, lipid lowering), and development of maintenance programs.9,15

Variables

The following patient characteristics were recorded: (1) demographics: age, gender, body mass index (BMI); (2) length of stay: rehabilitation beginning and end; (3) risk factors (diabetes mellitus, hyperlipoproteinemia, arterial hypertension, smoking, positive cardiac family history); (4) concomitant diseases: peripheral arterial disease, previous stroke; (5) systolic and diastolic blood pressure at entry and discharge; (6) laboratory parameters at entry and discharge: total cholesterol (TC, mg/dL), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C, mg/dL), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, mg/dL), triglycerides (TG, mg/dL), fasting blood glucose (mg/dL); (7) cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Watts); (8) medication use at entry and discharge: statins, acetylic salicylic acid (ASA, aspirin), beta blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARB), oral antidiabetic drugs, insulin, and other drugs.

Patients were categorized as having MetS if they met the definition of the IDF 20057 (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Parameter | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Central obesity | Defined as waist circumference ≥94 cm for European men and ≥80 cm for European women, with ethnicity specific values for other groups* |

| plus any two of the following four factors: | |

| Raised TG | ≥1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dL) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality |

| Reduced HDL-C | <1.03 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) in males <1.29 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) in females or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality |

| Raised blood pressure | Systolic: ≥130 mmHg or diastolic: ≥85 mmHg or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension |

| Raised plasma glucose** | Fasting plasma glucose ≥5.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes |

Notes:

If BMI is >30 kg/m2, central obesity can be assumed and waist circumference does not need to be measured;

In clinical practice, impaired glucose tolerance is also acceptable, but all epidemiological reports of the prevalence of MetS should use only fasting plasma glucose and presence of previously diagnosed diabetes to assess this criterion. Prevalence also incorporating 2-hour glucose results can be added as supplementary findings.

Abbreviations: IDF, International Diabetes Federation; MetS, metabolic syndrome; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; BMI, body mass index.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as absolute numbers, percentages, or means with standard deviations (SD). The frequencies of categorical variables in populations were compared by Chi square test. Continuous variables were compared by two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test. Percentages were calculated on the basis of patients with data for each respective parameter (ie, no percentages for missing values provided). The analysis was performed with the SAS (v9.1; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics

Total cohort

A total of 27,904 patients with information on MetS (15,819 with MetS/12,085 without MetS) were available (in 2005: 5805; 2006: 8839; 2007: 5753; 2008: 7507 patients). The majority of patients were fully or partly institutionalized for CR (95.3% or 1.4%, respectively). Mean duration of rehabilitation was 21.4 ± 37.5 days, with a trend towards an increase over the years (2005: 19.8 days; 2006: 20.3 days; 2007: 22.9 days; 2008: 22.7 days). The majority of patients were retired (61.5%).

Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The proportion of males in total was 71.7%, the average age 64.3 ± 11.5 years, the mean BMI was 28.4 ± 4.8 kg/m2. Cardiovascular risk factors were highly prevalent as expected, in particular lipid disorders (97.1%), diabetes mellitus (35.7%), arterial hypertension (86.9%), and former or current smoking (47.7% and 15.7%, respectively). In addition to coronary artery disease, 12.2% of patients also had peripheral artery disease, and 8.8% had had a prior stroke event.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical factors in patients with and without MetS

| Parameter | Total n = 27,904 | MetS n = 15,819 | No MetS n = 12,085 | P value* | Odds ratio* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years | 64.3 ± 11.5 | 64.6 ± 11.2 | 63.9 ± 11.8 | <0.0001 | |

| Gender, male, % | 71.7 | 67.6 | 77.2 | <0.0001 | 0.62 |

| Weight, kg | 82.4 ± 16.1 | 87.0 ± 16.2 | 76.4 ± 13.8 | <0.0001 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.37 ± 4.78 | 30.0 ± 4.71 | 26.24 ± 3.95 | <0.0001 | |

| Waist circumference, cm | 99.5 ± 13.5 | 105.0 ± 11.8 | 92.5 ± 12.2 | <0.0001 | |

| Diagnosis for CR | |||||

| STEMI, % | 41.1 | 38.7 | 44.3 | <0.0001 | 0.79 (0.76–0.83) |

| NSTEMI, % | 21.8 | 21.7 | 21.9 | 0.72 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) |

| Unstable angina pectoris, % | 16.7 | 17.3 | 15.9 | <0.01 | 1.10 (1.04–1.18) |

| Therapy in acute hospital | |||||

| PCI, % | 55.1 | 52.7 | 58.3 | <0.0001 | 0.80 (0.76–0.84) |

| Coronary artery bypass, % | 39.5 | 42.2 | 35.9 | <0.0001 | 1.30 (1.24–1.37) |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 35.7 | 52.1 | 14.0 | <0.0001 | 6.66 (6.26–7.08) |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 97.1 | 97.7 | 96.3 | <0.0001 | 1.63 (1.42–1.88) |

| Arterial hypertension, % | 86.9 | 94.6 | 76.8 | <0.0001 | 5.26 (4.85–5.70) |

| Smoking, current, % | 15.7 | 14.4 | 17.5 | <0.0001 | 0.79 (0.74–0.85) |

| Smoking, previous, % | 47.7 | 48.0 | 47.2 | 0.23 | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) |

| Peripheral arterial disease, % | 12.2 | 12.9 | 11.3 | <0.0001 | 1.16 (1.08–1.25) |

| Previous stroke, % | 8.8 | 9.4 | 8.0 | <0.0001 | 1.19 (1.10–1.30) |

| Positive family history, % | 30.5 | 31.3 | 29.5 | 0.01 | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) |

Note:

P values and odds ratios refer to the comparison between the two groups (MetS versus no MetS) at entry.

Abbreviations: MetS, metabolic syndrome; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) were the largest group (41.1% of patients), followed by non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI; 21.8%) and instable angina pectoris (16.7%). In terms of therapy at the acute hospital, percutaneous coronary intervention was more often reported compared to coronary artery bypass graft (55.1% versus 39.5%, respectively).

Subgroups with and without MetS

Due to the large sample size, statistically significant differences between the two subgroups were noted for all mentioned demographic and clinical characteristics with the exception of NSTEMI. Patients with MetS compared to those without MetS were less frequently men, and naturally differed with respect to components of the MetS definition (having a higher BMI, a higher waist circumference, more often hypertension, and substantially more often diabetes (52% versus 14%, respectively). Mean fasting glucose was higher in patients with MetS compared to those without MetS (115 mg/dL versus 98 mg/dL), as was glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c; 6.6% versus 6.1%). In terms of cardiac interventions, patients with MetS more often received coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Drug utilization

Total cohort

Drug treatment at entry and discharge is shown in Table 3. In the total cohort, the majority of patients received statins at entry (any drug in 79.9%). In particular, simvastatin (61.0%, at a mean dose of 30.4 mg/day), atorvastatin (7.0%, mean dose 28.9 mg/day), and fluvastatin (7.9%, mean dose 60.2 mg/day) were reported. At the end of CR stay, almost all patients received statin therapy (any statin in 95.2%). The rates of simvastatin use increased, while all other statins decreased somewhat. Furthermore, overall the respective mean dosages increased slightly, eg, for atorvastatin to 32.3 mg/day.

Table 3.

Drug treatment at entry and discharge

| Parameter | Total n = 27,904 | MetS n = 15,819 | No MetS n = 12,085 | P value* | Odds ratio* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statins, any % | 79.9 → 95.2 | 79.7 → 95.2 | 80.2 → 95.4 | 0.30 → 0.40 | 0.97 → 0.95 |

| Simvastatin, % | 61.0 → 83.2 | 60.6 → 82.7 | 61.6 → 83.8 | 0.08 → <0.05 | 0.96 → 0.92 |

| Dose, mg/day ± SD | 30.4 ± 12.7 → 31.3 ± 13.9 | 30.5 ± 12.7 → 31.3 ± 13.9 | 30.3 ± 12.6 → 31.4 ± 13.9 | 0.34 → 0.41 | |

| Pravastatin, % | 3.8 → 2.0 | 3.8 → 2.0 | 3.8 → 2.0 | 0.97 → 0.85 | 1.00 → 1.02 |

| Atorvastatin, % | 7.0 → 4.4 | 7.1 → 4.5 | 6.7 → 4.2 | 0.22 → 0.37 | 1.06 → 1.05 |

| Fluvastatin, % | 7.9 → 5.5 | 8.0 → 5.7 | 7.8 → 5.2 | 0.69 → <0.05 | 1.02 → 1.11 |

| Other statin, % | 0.5 → 1.8 | 0.5 → 1.8 | 0.4 → 1.8 | 0.24 → 0.86 | 1.23 → 0.98 |

| CAI, % | 7.2 → 47.2 | 7.6 → 47.0 | 6.7 → 47.3 | <0.01 → 0.65 | 1.14 → 0.99 |

| ASA, % | 83.8 → 84.2 | 83.0 → 83.4 | 84.8 → 85.2 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 0.88 → 0.87 |

| ASA clopidogrel, % | 45.2 → 42.0 | 42.2 → 39.0 | 49.2 → 46.0 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 0.76 → 0.75 |

| Beta blocker, % | 86.2 → 89.5 | 87.1 → 90.3 | 85.0 → 88.6 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 1.19 → 1.20 |

| ACE inhibitor, % | 71.5 → 72.6 | 72.0 → 73.3 | 70.9 → 71.6 | <0.05 → <0.01 | 1.05 → 1.09 |

| ARB, % | 12.4 → 16.3 | 14.0 → 18.4 | 10.4 → 13.6 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 1.41 → 1.44 |

| Oral antidiabetic drug, % | 15.3 → 16.9 | 22.9 → 25.3 | 5.3 → 6.1 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 5.3 → 5.23 |

| Insulin, % | 12.3 → 12.6 | 18.1 → 18.5 | 4.7 → 4.8 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 4.49 → 4.54 |

Notes:

P values and odds ratios refer to the comparison between the two groups (MetS versus no MetS) at entry. Values are percentages at entry and → at discharge.

Abbreviations: MetS, metabolic syndrome; SD, standard deviation; CAI, cholesterol absorption inhibitor; ASA, acetylic salicylic acid; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Treatment with cholesterol absorption inhibitors increased substantially during the CR (from 7.2% to 47.2%). ASA use remained nearly unchanged at a high level (at discharge 84.2%), while clopidogrel alone or in combination with ASA decreased somewhat. ACE inhibitors and ARBs were frequently used in this study (at discharge 72.6% and 16.3%, respectively).

Subgroups with and without MetS

In the statistical comparison, there were statistically significant differences for almost all drug classes between patients without MetS and those with MetS. To note major differences, patients with MetS had more frequent use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs (at entry and discharge), and less frequent use of clopidogrel and ASA/clopidogrel combinations. With respect to antidiabetic medications, patients with MetS had higher use of oral antidiabetic drugs (22.9% versus 5.3% at entry and 25.3% versus 6.1% at discharge) and insulin (18.1% versus 4.7% at entry and 18.5% versus 4.8% at discharge).

Target level attainment

Total cohort

Lipid levels, other surrogate parameters, and target level attainment at entry and at discharge are shown in Table 4. In the total cohort at entry mean TC was 184.9 mg/dL, mean LDL-C 113.8 mg/dL, mean HDL-C 43.2 mg/dL, and mean TG 157.4 mg/dL.

Table 4.

Parameters and treatment goal achievement at entry and discharge

| Parameter | Total n = 27,904 | MetS n = 15,819 | No MetS n = 12,085 | P value* | Odds ratio* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (mg/dL) | 184.9 ± 48.0 → 152.6 ± 36.1 | 184.8 ± 49.6 → 151.0 ± 37.0 | 185.1 ± 45.3 → 155.0 ± 35.2 | <0.05 → <0.0001 | NA |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 113.8 ± 39.1 → 86.1 ± 28.6 | 113.9 ± 40.1 → 85.4 ± 28.9 | 113.7 ± 37.6 → 87.1 ± 28.0 | 0.26 → <0.0001 | NA |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 43.2 ± 12.8 → 43.2 ± 12.0 | 39.9 ± 11.1 → 40.2 ± 10.6 | 48.2 ± 13.6 → 47.7 ± 12.7 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | NA |

| TG (mg/dL) | 157.4 ± 81.0 → 136.1 ± 71.3 | 178.1 ± 94.5 → 149.8 ± 76.1 | 126.0 ± 62.2 → 115.3 ± 57.4 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | NA |

| Guideline achievement | |||||

| LDL-C <100 mg/dL | 38.7 → 73.8 | 39.4 → 74.6 | 37.5 → 72.8 | <0.01 → <0.01 | 1.08 → 1.10 |

| TC <200 mg/dL | 66.7 → 90.3 | 66.4 → 90.7 | 67.3 → 89.8 | 0.12 → <0.05 | 0.96 → 1.10 |

| HDL-C > 50 (w)/> 40 mg/dL (m) | 44.0 → 44.4 | 27.4 → 30.8 | 69.2 → 64.9 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 0.17 → 0.24 |

| TG < 150 mg/dL | 58.1 → 70.4 | 43.7 → 62.2 | 80.0 → 82.8 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 0.19 → 0.34 |

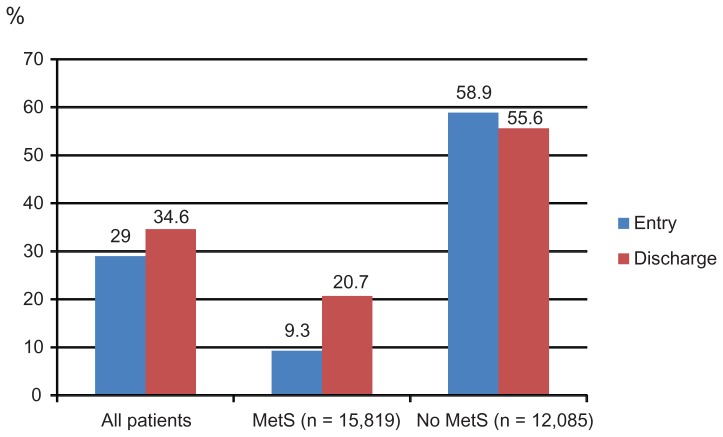

| HDL-C > 50/40 mg/dL + TG < 150 mg/dL | 29.0 → 34.6 | 9.3 → 20.7 | 58.9 → 55.6 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 0.07 → 0.21 |

| LDL-C < 100 mg/dL + HDL-C > 50 or 40 mg/dL + TG < 150 mg/dL | 11.5 → 25.9 | 4.2 → 15.9 | 22.5 → 41.1 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | 0.15→ 0.27 |

| Systolic/diastolic BP at entry and discharge (mmHg) | 130.5 ± 20.3/76.5 ± 11.5 → 122.3 ± 14.4/72.7 ± 9.3 | 132.8 ± 20.5/77.2 ± 11.7 → 123.9 ± 14.4/73.1 ± 9.4 | 127.4 ± 19.6/75.7 ± 11.2→ 120.2 ± 14.1/72.2 ± 9.1 | <0.0001/<0.0001 → <0.0001/0.0001 | NA |

| HbA1c (%) (entry only) | 6.5 ± 1.1 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | <0.0001 | NA |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 ± 0.9 → 1.3 ± 0.95 | 1.2 ± 0.9 → 1.3 ± 0.95 | 1.2 ± 0.9 → 1.2 ± 0.95 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | NA |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 108.1 ± 33.3 → 103.3 ± 27.0 | 115.08 ± 36.21 → 108.57 ± 29.23 | 97.63 ± 25.01 → 94.53 ± 20.03 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | NA |

| Max exercise (Watts) | 77.3 ± 37.0 → 93.7 ± 39.3 | 75.5 ± 36.4 → 91.1 ± 38.8 | 79.3 ± 37.5 → 96.9 ± 39.6 | <0.0001 → <0.0001 | NA |

Notes:

P values and odds ratios refer to the comparison between the two groups (MetS vs no MetS) at entry and (indicated by the arrow →) at discharge.

Abbreviations: MetS, metabolic syndrome; TC, total cholesterol; NA, not applicable; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; w, women; m, men; BP, blood pressure; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c values refer to entry visit).

At discharge, mean values had considerably improved (TC 152.6 mg/dL, LDL-C 86.1 mg/dL, and TC 136.1 mg/dL), while HDL-C remained unchanged.

Figure 1A–E display control rates of various lipid parameters alone and in combination at entry and discharge, in the total cohort and by subgroup. Overall, between entry and discharge, control rates of lipid parameters improved substantially, with the exception of HDL-C. The LDL-C goal (<100 mg/dL) was achieved at entry by 38.7% of patients and at discharge by 73.8%, the TC goal (<200 mg/dL) at entry by 66.7% of patients and at discharge by 90.3%, the HDL-C goal (>50 mg/dL in women; >40 mg/dL in men) at entry by 44.0% of patients and at discharge by 44.4%. Furthermore, the TG goal of <150 mg/dL was met at entry by 58.1% of patients and at discharge by 70.4%. Combined lipid goals for HDL-C + TG were reached by 29.0% of patients at entry and by 34.6% at discharge; for LDL-C + HDL-C + TG by 11.5% at entry and by 25.9% at discharge.

Figure 1A.

LDL-C control rates.

Notes: LDL-C control was defined as <100 mg/dL.

Abbreviations: LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome.

Figure 1E.

Combined control rates (LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG).

Notes: LDL-C control was defined as <100 mg/dL. HDL-C control was defined as >50 mg/dL in females and >40 mg/dL in males. TG control was defined as <150 mg/dL.

Abbreviations: LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; MetS, metabolic syndrome.

Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure were decreased to 122/72 mmHg (entry: 130/77 mmHg), and the maximum exercise capacity increased to 94 Watts (entry: 77 Watts). Mean fasting blood glucose decreased from 108 mg/dL to 103 mg/dL. HbA1c was only available at entry (mean: 6.5%).

Subgroups with and without MetS

Mean HDL-C was lower and mean TG were substantially higher in MetS patients compared to those without MetS. Target level attainment rates for LDL-C were somewhat higher for patients with MetS at entry, but much lower for HDL-C and TG (Table 4). This also applied for the combined lipid goals. This pattern did not change at the discharge visit, but overall control rates for all described single parameters (with the exception of HDL-C) had improved substantially.

Mean blood pressure did not differ substantially between groups at discharge, and was in the normal range. Exercise capacity was lower in patients with MetS (91 versus 97 Watts). Fasting blood glucose (as a component of the MetS definition), was higher in the MetS group and was substantially decreased at discharge. HbA1c was slightly worse in MetS patients compared to those without MetS at entry.

Discussion

The present analysis provides a snapshot of the characteristics, treatment, and risk factor control of patients with MetS in the CR setting in Germany. More than half of patients had MetS. Irrespective of whether MetS was present or not, patients experienced substantial improvement in particular with respect to lipid parameters, but also physical training.

Patient characteristics

Patients with or without MetS were similar in terms of gender distribution and age. The latter finding is notable, because in patients with higher body weight myocardial events tend to occur at a younger age (eg, in the CRUSADE registry mean age at first NSTEMI was 75 years in patients with BMI <18.5 kg/m2, and 59 years in patients with BMI > 40 kg/m2).18 Patients with MetS as stipulated by the definition of the syndrome were more often obese, and more often had diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension. Furthermore, they received more antidiabetic or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system acting drugs, while the utilization of lipid lowering drugs was similar to patients without MetS. According to our thorough literature search, only one small study has reported in detail the prevalence and profile of MetS in CR following acute coronary syndromes.19 In a cohort of 225 patients, age (66.7 years) and gender distribution (men 71%) was similar to our study, and a similar proportion (58%) had MetS according to NCEP ATP III criteria, and 65% were on statins. In that study, 3 months’ outpatient treatment reduced the mean number of metabolic derangements significantly (from 3.3 to 2.8), and owing to these changes, the prevalence of MetS decreased to 53% in the total cohort.

Definition of MetS

Our analysis was limited to the IDF definition of MetS, and we did not investigate other definitions. Milionis et al have stated in a comparison of three definitions (NCEP ATP III5, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association, and IDF), that the latter markedly increased prevalence compared with the other criteria.20 In a Greek study representing the overall population, adopting the IDF definition increased the prevalence of MetS substantially compared with NCEP ATP III criteria (IDF 43.4% versus NCEP 24.5%).21 As this was a retrospective analysis, physicians were not aware of the MetS condition, unless they diagnosed it themselves. As the value of the MetS diagnosis (beyond its components) compared to simpler risk assessment tools is controversial,22,23–25 the effect on the treatment of individual risk factors was independent from this diagnosis.

The target values for lipids,26 blood pressure,27 or blood glucose28 and the medication recommendations for patients with coronary heart disease do not differ in the CR setting29 from patients seen by family physicians. In a previous analysis of the dataset, we had noted that drug treatment in CR appears to have been intensified (in terms of drug classes, drugs, and doses) compared to previous years.17

An aspect that deserves particular attention is the physical fitness of patients. Previous studies have shown that poor physical fitness is associated with MetS.7,11,25 The combination of both MetS and low fitness (as evidenced by high heart rate ≥ 83 beats per minute in another study) has very recently been reported to be associated with an almost fourfold increased risk for cardiovascular disease.30 In our study, patients in both the MetS and non-MetS groups achieved a considerable gain in exercise capacity (in Watts) during CR which might contribute to improved prognosis in the long term.

Treatment

Treatment rates with cholesterol absorption inhibitors increased substantially during CR in patients with or without MetS, while statins in terms of drugs and doses were infrequently changed. The leading statin in practice and in the present study was simvastatin, which is usually administered at doses of 20–40 mg/day for coronary heart disease prevention. High simvastatin doses have been associated with increased risk of myopathy, which might discourage physicians to increase doses.31 Furthermore, substantial combination data are available for simvastatin/cholesterol absorption inhibitors32 and, as in other indications (such as arterial hypertension or chronic heart failure), combination treatment appears adequate in patients who have not achieved their treatment targets on monotherapy.

Control of risk factors

Despite the relatively short duration of CR stays, a substantial improvement in lipid parameters was achieved. In particular, TG in the MetS group was reduced from 178 to 149 mg/dL, an effect that was much stronger than in the group without MetS. In addition, in the MetS group effects on TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C were stronger than in the group without MetS. Both groups benefited in terms of a notable blood pressure reduction and a reduction of fasting blood glucose at discharge compared to entry. If the lipid control rates as stipulated by the respective guidelines (eg, LDL-C target < 100 mg/dL) are taken into account, a substantial improvement after the CR stay was also noted (with the exception of HDL-C). Nonetheless, as in previous studies of patients with coronary heart disease in the primary care setting33,34 there is further room for improvement in the lipid values,35,36 HbA1c,37 and blood pressure control rates.38 Physicians in rehabilitation have to initiate lifestyle modifications or drug treatment (about 3–4 weeks), and face the complexity of coronary heart disease patients who often have concomitant diseases.39

Methodological aspects

Among the strengths of the registry are its prospective conduct, its large size and representativeness for the German CR setting, as well as various quality measures (plausibility checks and others). However, selection bias cannot be excluded for physicians (those voluntarily participating in a registry are more likely to have an interest and probably increased knowledge in the topic) and patients (participants may be more adherent to therapy compared to those declining). In addition, missing data or under-reporting of characteristics may decrease robustness of results. We did not collect data on further potentially informative parameters such as uric acid, pro-coagulation, or inflammatory markers.

Conclusion

We found that the proportion of patients with MetS was very high among patients who were enrolled in CR programs. Within a short period of, on average, 3–4 weeks, CR programs led to considerable improvements in patients irrespective of MetS status in terms of mean TC, LDL-C, and TG levels (HDL-C levels also improved in MetS patients). A substantial improvement of risk factors including hypertension and high blood glucose was achieved. Physical fitness that can lower the risk of cardiovascular disease improved in MetS patients to a stronger degree than in patients without MetS. While overall control rates for lipids, blood pressure, and blood glucose are not yet optimal, patients with MetS gain substantial benefit from participation in CR programs.

Figure 1B.

HDL-C control rates.

Notes: HDL-C control was defined as >50 mg/dL in females and >40 mg/dL in males.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome.

Figure 1C.

TG control rates at entry and discharge.

Notes: TG control was defined as <150 mg/dL.

Abbreviations: TG, triglycerides; MetS, metabolic syndrome.

Figure 1D.

Combined control rates (HDL-C and TG).

Notes: HDL-C control was defined as >50 mg/dL in females and >40 mg/dL in males. TG control was defined as <150 mg/dL.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; MetS, metabolic syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The TROL registry was conducted in cooperation with the German Society for Prevention and Rehabilitation. It was supported by MSD Sharp and Dohme GmbH, Munich-Haar, Germany. CJ and BK are fulltime employees of MSD. All authors are in the Steering Board or Scientific Board of the study. We acknowledge the input of D Pittrow, Institute for Clinical Pharmacology, Technical University Dresden, for interpretation of the data and various sections of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;2010;56(25):e50–e103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: 1999. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Report of a WHO Consultation. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerner W, Brückel J, Böhm B. Definition, classification and diagnostics of diabetes mellitus. In: Scherbaum WA, Kiess W, editors. Guidelines of the German Diabetes Society [Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft DDG] German: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Einhorn D, Reaven GM, Cobin RH, et al. American College of Endocrinology position statement on the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2003;9(3):237–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloomgarden ZT. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) consensus conference on the insulin resistance syndrome: August 25–26, 2002, Washington, DC. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):933–939. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Internation Diabetes Federation. IDF worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. [Accessed on December 22, 2010]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/idf-worldwide-definition-metabolic-syndrome.

- 8.Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):892–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karoff M, Held K, Bjarnason-Wehrens B. Cardiac rehabilitation in Germany. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(1):18–27. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280128bde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haskell WL, Alderman EL, Fair JM, et al. Effects of intensive multiple risk factor reduction on coronary atherosclerosis and clinical cardiac events in men and women with coronary artery disease. The Stanford Coronary Risk Intervention Project (SCRIP) Circulation. 1994;89(3):975–990. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niebauer J, Hambrecht R, Velich T, et al. Attenuated progression of coronary artery disease after 6 years of multifactorial risk intervention: role of physical exercise. Circulation. 1997;96(8):2534–2541. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280(23):2001–2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor GT, Buring JE, Yusuf S, et al. An overview of randomized trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1989;80(2):234–244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willich SN, Muller-Nordhorn J, Kulig M, et al. Cardiac risk factors, medication, and recurrent clinical events after acute coronary disease; a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(4):307–313. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bestehorn K, Wegscheider K, Voller H. Contemporary trends in cardiac rehabilitation in Germany: patient characteristics, drug treatment, and risk-factor management from 2000 to 2005. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15(3):312–318. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f40e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.German Society for Prevention and Rehabilitation of Cardiovascular Disease [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Prävention und Rehabilitation von Herz-Kreislauferkrankungen e.V., Koblenz, Germany] German: [Accessed March 28, 2012]. Available from: http://www.dgpr.de. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Völler H, Reibis R, Pittrow D, et al. Secondary prevention of diabetic patients with coronary artery disease in cardiac rehabilitation: risk factors, treatment and target level attainment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(4):879–890. doi: 10.1185/03007990902801360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madala MC, Franklin BA, Chen AY, et al. Obesity and age of first non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(12):979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Prevalence and profile of metabolic syndrome in patients following acute coronary events and effects of therapeutic lifestyle change with cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(1):50–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milionis HJ, Kostapanos MS, Liberopoulos EN, et al. Different definitions of the metabolic syndrome and risk of first-ever acute ischaemic non-embolic stroke in elderly subjects. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(4):545–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Athyros VG, Ganotakis ES, Elisaf M, Mikhailidis DP. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome using the National Cholesterol Educational Program and International Diabetes Federation definitions. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(8):1157–1159. doi: 10.1185/030079905x53333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn R, Buse J, Ferrannini E, Stern M. The metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal: joint statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2289–2304. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahn R. Metabolic syndrome – what is the clinical usefulness? Lancet. 2008;371(9628):1892–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60731-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sattar N, McConnachie A, Shaper AG, et al. Can metabolic syndrome usefully predict cardiovascular disease and diabetes? Outcome data from two prospective studies. Lancet. 2008;371(9628):1927–1935. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundy SM. Does a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome have value in clinical practice? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1248–1251. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryden L, Standl E, Bartnik M, et al. Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: executive summary: The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Eur Heart J. 2007;28(1):88–136. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balady GJ, Ades PA, Comoss P, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing Group. Circulation. 2000;102(9):1069–1073. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Hartaigh B, Jiang CQ, Thomas GN, et al. Usefulness of physical fitness and the metabolic syndrome to predict vascular disease risk in older Chinese (from the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study-Cardiovascular Disease Subcohort [GBCS-CVD]) Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(6):845–850. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) FDA Drug Safety Communication: New restrictions, contraindications, and dose limitations for Zocor ( simvastatin) to reduce the risk of muscle injury. [Accessed March 27, 2012]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm256581.htm.

- 32.Ijioma N, Robinson JG. Lipid-lowering effects of ezetimibe and simvastatin in combination. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;9(2):131–145. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bestehorn K, Jannowitz C, Karmann B, Pittrow D, Kirch W. Characteristics, management and attainment of lipid target levels in patients enrolled in Disease Management Program versus those in routine care: LUTZ registry. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gitt AK, Juenger C, Jannowitz C, Karmann B, Senges J, Bestehorn K. Guideline-oriented ambulatory lipid-lowering therapy of patients at high risk for cardiovascular events by cardiologists in clinical practice: the 2L cardio registry. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(4):438–444. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832a4e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gitt AK, Junger C, Smolka W, Bestehorn K. Prevalence and overlap of different lipid abnormalities in statin-treated patients at high cardiovascular risk in clinical practice in Germany. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99(11):723–733. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0177-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Böhler S, Scharnagl H, Freisinger F, et al. Unmet needs in the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia in the primary care setting in Germany. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190(2):397. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pittrow D, Stalla GK, Zeiher AM, et al. Prevalence, drug treatment and metabolic control of diabetes mellitus in primary care. Med Klin (Munich) 2006;101(8):635–644. doi: 10.1007/s00063-006-1093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma A, Wittchen H, Kirch W, et al. High prevalence and poor control of hypertension in primary care: cross sectional study. J Hypertens. 2004;22:479–486. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittrow D, Kirch W, Bramlage P, et al. Patterns of antihypertensive drug utilization in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60(2):135–142. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magliano DJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ. How to best define the metabolic syndrome. Ann Med. 2006;38(1):34–41. doi: 10.1080/07853890500300311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]