Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence of single and mixed dyslipidemias among patients treated with statins in clinical practice in France.

Methods

This is a prospective, observational, cross-sectional, pharmacoepidemiologic study with a total of 2544 consecutive patients treated with a statin for at least 6 months.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of isolated and mixed dyslipidemias of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides among all patients and among patients at high cardiovascular risk; clinical variables associated with attainment of lipid targets/normal levels in French national guidelines.

Results

At least one dyslipidemia was present in 50.8% of all patients and in 71.1% of high-risk patients. Dyslipidemias of LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides were present in 27.7%, 12.4%, and 28.7% of all patients, respectively, and in 51.0%, 18.2%, and 32.5% of high-risk patients, respectively. Among all subjects with any dyslipidemia, 30.9% had mixed dyslipidemias and 69.4% had low HDL-C and/or elevated triglycerides, while 30.6% had isolated elevated LDL-C; corresponding values for high-risk patients were 36.8%, 58.9%, and 41.1%. Age, gender, body mass index and Framingham Risk Score >20% were the factors significantly associated with attainment of normal levels for ≥2 lipid levels.

Conclusions

At least one dyslipidemia persisted in half of all patients and two-thirds of high cardiovascular risk patients treated with a statin. Dyslipidemias of HDL-C and/or triglycerides were as prevalent as elevated LDL-C among high cardiovascular risk patients.

Keywords: cholesterol, triglycerides, dyslipidemias, prevalence, treatment outcome, France

Introduction

Elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is the primary treatment target for patients at risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).1,2 Hence, European guidelines for reducing cardiovascular risk focus on lowering serum levels of LDL-C (and total cholesterol [TC]).2,3 However, low serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and elevated levels of triglycerides also increase the risk of CHD,4–9 even in patients treated with statins and with low LDL-C levels.9 Serum levels of HDL-C and triglycerides tend to be inversely correlated, likely reflecting their respective participation in lipid transport and reverse cholesterol transport.10 The inverse relationship holds in the effects of lipid-modifying drugs – niacin,11 fibrates,11 statins,12,13 and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors,14 all concomitantly increase HDL-C and decrease triglyceride levels – and in the effects of certain genetic mutations.15–21 This suggests that the separate dyslipidemias of low HDL-C and elevated triglycerides may be viewed in combination.

Previous studies of dyslipidemia in primary care in France have either focused on LDL-C and/or TC22–24 or have reported values for individual lipids (TC and triglycerides;25 LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides26) according to NCEP ATP III guidelines.25,26 Studies of mixed dyslipidemias in European countries have applied NCEP ATP III guidelines27 or modified JES III guidelines.28 Studies set in primary care in France have reported rates of mixed dyslipidemias of LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides according to European JES III guidelines, published in 2003.29,30 Bruckert et al reported rates of mixed dyslipidemias of HDL-C and triglycerides in 11 European countries, including France, according to JES III and NECEP ATP III guidelines.31

In France the Agence Française de Securite Sanitaire des Produits de Sante (AFSSAPS) has developed national guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia that differ in important ways from the European guideline.32 In particular, the thresholds for LDL-C for patients not categorized as high risk differ in the AFSSAPS and JES IV guidelines, and in AFSSAPS the threshold for HDL-C is the same for men and women (Table 1). Currently, the AFSSAPS are the most commonly used and recommended guidelines for patients treated with lipid-modifying therapy in France. Accordingly, prior studies assessing achievement of target LDL-C levels among statin-treated patients in France have applied the AFSSAPS definition.23,33,34 The objective of this paper is to further evaluate single and mixed dyslipidemias among patients treated with statins in clinical practice in France, applying the AFSSAPS guidelines.

Table 1.

Comparison of French (AFSSAPS) and European guidelines lipid thresholds for dyslipidemia

| Lipid parameter | French (AFSSAPS)33 | European guideline (JES IV)2 |

|---|---|---|

| LDL-C | ||

| High risk*,† | <100 mg/dL | <100 mg/dL (option of <80 mg/dL) |

| Not high risk‡ | ||

| ≥3 risk factors | <130 mg/dL | <115mg/dL |

| 2 risk factors | <160 mg/dL | <115mg/dL |

| 1 risk factor | <190 mg/dL | <115mg/dL |

| 0 risk factors | <220 mg/dL | <115mg/dL |

| HDL-C | ||

| Men | <40 mg/dL | <40 mg/dL |

| Women | <40 mg/dL | <45 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | >150 mg/dL | >150 mg/dL |

Notes:

High cardiovascular risk was defined in the French guideline by a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, a diagnosis of high-risk type 2 diabetes, and/or a 10-year CHD risk >20%.33 High-risk diabetes was defined as diabetes mellitus with concomitant renal disease and/or at least two of the following cardiovascular risk factors: age, family history of coronary disease, HDL-C <40 mg/dL, and microalbuminuria (>30 mg/24 hours).33

In the JES IV guideline, the following high-risk patient groups have priority in lipid treatment: (1) those with established CVD; (2) asymptomatic individuals with (a) multiple risk factors resulting in ≥5% risk of CV-related death in the next 10 years, (b) diabetes, or (c) markedly increased single risk factors; and (3) those with a family history of early CVD or high CV risk. Factors used to calculate risk are age, sex, smoking status, total cholesterol, and blood pressure.

Risk factors in the French guideline were age (≥50 for men and ≥60 for women); tobacco use (currently smoking or stopped <3 years earlier); a family history of early-onset coronary disease (MI or sudden death before age 55 in the father or first-degree male relative, and MI or sudden death before age 65 in the mother or first-degree female relative); permanent hypertension (diagnosis of hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg) or treatment with antihypertensive agents); type 2 diabetes (treatment with anti-diabetic agent or diagnosis of diabetes); and HDL-C <40 mg/dL regardless of gender.33

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a prospective, observational, cross-sectional, pharmacoepidemiologic study of patients receiving lipid-modifying therapies that included a statin. The data source was the 2006 BKL-Thales database.22,33–38 Physicians in the Thales panel compose a nationally representative sample, based on criteria of age, gender, and area of practice. They maintain their patients’ medical and prescription records using proprietary computer software and transmit coded extracts into the Thales database. To collect additional data for this study, a supplementary questionnaire was added to the physicians’ software program. No intervention was made to affect the physicians’ prescribing behavior and the identities of neither the physicians nor patients were recorded in the data set analyzed.

Study sample

The source population consisted of consecutive patients who agreed to participate in the supplementary survey during a routine visit to a general practitioner belonging to the Thales network. Physicians recruited dyslipidemic patients who had been treated with a statin for at least 6 months and who had a complete lipid profile (LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides) within the past 6 months. Patients were excluded from the study if their statin treatment had been modified (indicated by a change in International Nonproprietary Name [INN] or daily dosage) in the 3 months prior to the lipid panel or if they declined to participate.

The 2006 Thales database contains records of the lipid-modifying drug treatment of approximately 150,000 patients by 1200 physicians. The sample size necessary to show that 30% of patients had not attained their LDL-C target with an alpha of 0.05, a delta of 1.6%, and a power of 95% was calculated to be 3151. The target sample size was thus 3000.

Data collection

Seven hundred general practitioners were randomly selected from the Thales panel and sent letters inviting them to participate in the study. Three successive reminder letters were sent to physicians who did not respond. Patient data were collected prospectively via the computer network over a 6-month period from December 2007 to May 2008. Data were collected from existing medical records in the Thales database and via the computerized supplementary questionnaire. Data collected from existing records included the date of consultation, patient age, gender, diagnoses of hypertension and diabetes (treated or not), diagnosis of dyslipidemia, and prescription of a lipid-modifying agent. Data collected from the supplementary questionnaire included the patient’s weight, height, blood pressure, family history of early onset cardiovascular event, and smoking status (current or regular smoker, or stopped within past 3 months). Certain conditions were identified from a combination of the Thales data set and the supplementary questionnaire: proven coronary heart disease (CHD), proven cardiovascular disease (CVD), renal impairment, proteinuria, and microalbuminuria.

Definitions

Permanent hypertension was defined in the Thales data set as 140/90 mmHg (130/90 mmHg if diabetes present), measured as the mean of the last three values recorded. Proven CHD was defined in the Thales data set as a combination of a diagnosis of angina and three prescriptions per year of a nitrate derivative, beta-blocker, calcium channel inhibitor, or amiodarone. High cardiovascular risk was defined by a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, a diagnosis of high-risk type 2 diabetes, and/or a 10-year CHD risk >20% computed with the Framingham equation.39 High-risk diabetes was defined as diabetes mellitus with concomitant renal disease and/or at least two of the following cardiovascular risk factors: age, family history of coronary disease, HDL-C <40 mg/dL, and microalbuminuria (>30 mg/24 hours). Cardiovascular risk factors were as defined by the AFSSAPS 2005 French national guideline (Table 1).32 Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 and abdominal obesity as a waist measurement >88 cm in women and >102 cm in men. Thresholds for dyslipidemia were as defined in the AFSSPAS guideline (Table 1).32

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis of patient characteristics and the prevalence of individual dyslipidemias (of LDL-C, HDL-C, or triglycerides) was carried out. Seven categories of mutually exclusive dyslipidemias were defined:29 isolated elevated LDL-C, isolated low HDL-C, isolated elevated triglycerides, elevated LDL-C and low HDL-C, elevated LDL-C and elevated triglycerides, low HDL-C and elevated triglycerides, and all three lipid abnormalities. Combinations of two or more dyslipidemias were called ‘mixed’. The proportions of all combinations of normal and abnormal lipid values were determined for the total study population and for high-risk patients. The distribution of dyslipidemias among subjects with dyslipidemia was also reported. Clinical factors associated with attainment of AFSSAPS lipid threshold levels were assessed in multivariate regression models. The likelihood of attaining target/normal levels for individual lipid parameters, ie, LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides was computed, adjusting for age (per 1 year increase), gender, BMI category, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, Framingham score risk >20%, and year of index prescription (2008 versus 2007). The same covariates were adjusted for in an analysis of attainment of two or more lipid target/normal levels (among LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides) versus attainment of LDL-C only. Analyses were performed using SAS software (v 9; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study population

Patient characteristics

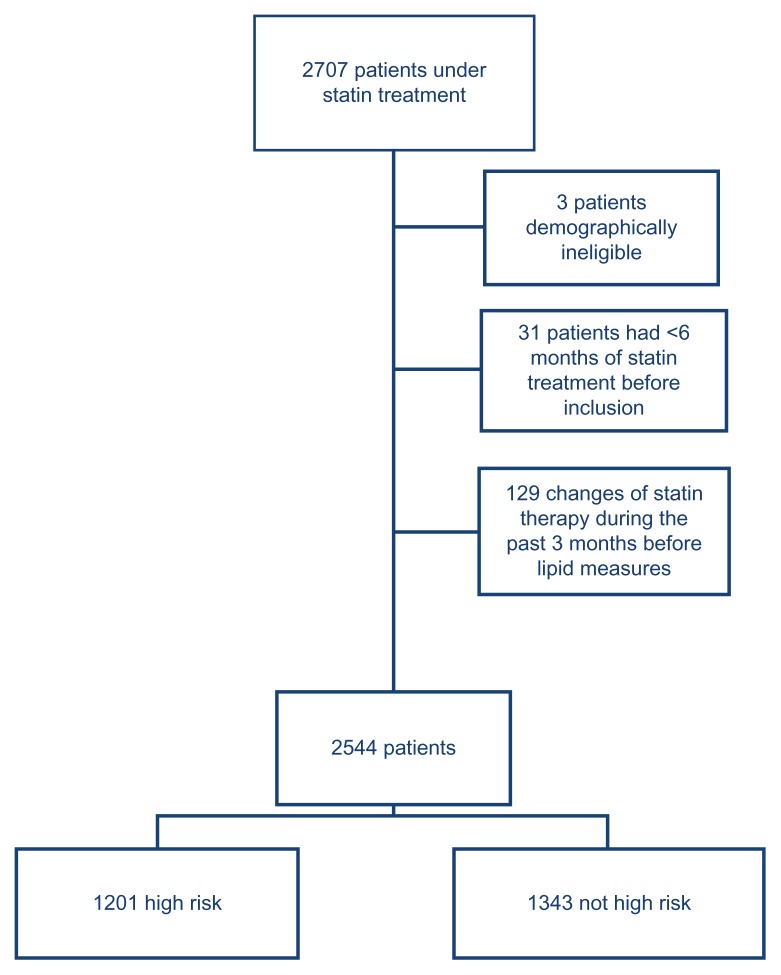

Of 2707 patients treated with a statin, 2544 met the study inclusion–exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of these, 1201(47.2%) were at high risk of cardiovascular events. The mean patient age was 65.8 years, 59.1% were men, and 71.7% had hypertension (Table 2). A history of cardiovascular disease was recorded for 31.8% of patients and 3.3% had a Framingham risk score >20%.

Figure 1.

Sample selection.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All patients (N = 2544) | High risk (N = 1201) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 65.75 (10.79) | 68.36 (9.79) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 1503 (59.08) | 885 (73.69) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||

| Current smoker, n (%) | 273 (10.73) | 138 (11.49) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1825 (71.74) | 961 (80.02) |

| Hypertension medication use, n (%) | 1584 ( 62.26) | 840 (69.94) |

| Systolic BP ≥140 mmHg, n (%) | 928 (36.48) | 506 (42.13) |

| Diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg, n (%) | 184 (7.23) | 93 (7.74) |

| Family history of CHD, n (%) | 392 (15.41) | 193 (16.07) |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| HBA1c,a mean (SD) | 6.92 (1.16) | 6.90 (1.18) |

| FBG,b mean (SD) | 1.36 (0.59) | 1.36 (0.61) |

| Diabetes medication use, n (%) | 631 (24.80) | 561 (46.71) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), n (%)c | ||

| 25% or less | 762 (30.23) | 308 (25.90) |

| >25% and <30% | 1103 (43.75) | 516 (43.40) |

| 30% or more (obesity) | 656 (26.02) | 365 (30.70) |

| Abdominal obesity,d n (%) | 763 (44.16) | 398 (48.54) |

| Menopause, n (% of women) | 190 (18.25)e | 49 (15.51 ) |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 60 (2.36) | 34 (2.83) |

| High cardiovascular riskf | ||

| 1. History of cardiovascular diseaseg n (%) | 809 (31.80) | 809 (67.36) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 440 (17.30) | 440 (36.64) |

| CHD, n (%) | 573 (22.52) | 573 (47.71) |

| 2. High-risk diabetes mellitus,h n (%) | 514 (20.20) | 514 (42.80) |

| 3. >20% 10-year risk, n (%) | 83 (3.26) | 83 ( 6.12) |

| Any of criteria (1)–(3), n (%) | 1201 (47.21) | 1201(100) |

Notes: All percentages referred to the overall sample in column 1 (2.544 patients) and to the overall number of high-risk patients in column 2, except for the following specific populations:

N = 590 (all patients), N = 524 (high risk);

N = 495 (all patients), N = 440 (high risk);

N = 2521 (all patients), N = 1189 (high risk);

N = 1728 (all patients), N = 820 (high risk);

190 women out of 1041; 49 women out of 316;

by French (AFSAPPS) criteria;33

CHD or ischemic stroke;

high-risk diabetes: patients with diabetes mellitus and at least two other cardiovascular risk factors or diabetes with a concomitant renal disease.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BP, blood pressure; CHD, coronary heart disease; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HBA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin.

Lipid-modifying drug therapies

Statin monotherapies were taken by 92.7% of the total patient sample (not tabulated). Statins were taken in combination with cholesterol absorption inhibitors by 4.8% and with other lipid-modifying therapies by 2.5% of patients. No patient received a statin in combination with a fibrate. Among the high-risk subgroup, 90.4% received statin monotherapies and statins were used in combination with cholesterol absorption inhibitors, omega-3 triglycerides, and other therapies by 7.2%, 2.8%, and 1.8% of patients, respectively.

Prevalence of dyslipidemias

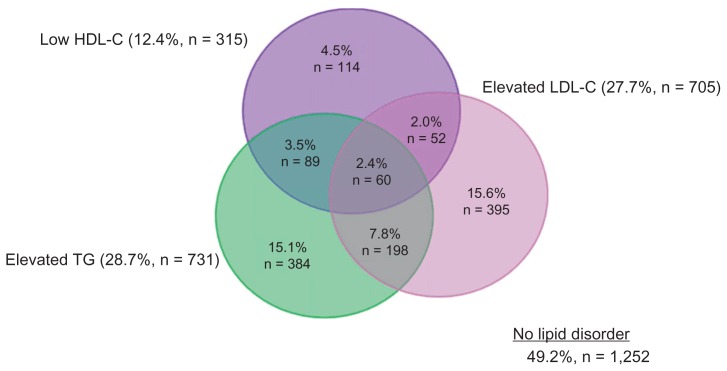

At least one dyslipidemia was present in 50.8% of all subjects. As seen in Figure 2, the most prevalent dyslipidemias in the entire population were elevated triglycerides (28.7%) and elevated LDL-C (27.7%), while 12.4% had low HDL-C. Among all subjects with any dyslipidemia, 30.9% had mixed dyslipidemias (Table 3). Low HDL-C and/or elevated triglycerides occurred in 69.4% of patients with any dyslipidemia, compared to 30.6% for isolated elevated LDL-C (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of dyslipidemias in all patients.*

Note: *N = 2,544 patients.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Table 3.

Prevalence of dyslipidemias among all subjects and high-risk subjects with at least one dyslipidemia

| Dyslipidemia(s) | All subjects (N = 1292) | High-risk subjects (N = 854) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Individual dyslipidemia | ||||

| Elevated LDL-Ca | 705 | 54.6% | 613 | 71.2% |

| Elevated triglyceridesa | 731 | 56.6% | 390 | 45.7% |

| Low HDL-Ca | 315 | 24.4% | 219 | 25.6% |

| Isolated dyslipidemia | ||||

| Elevated LDL-C alone | 395 | 30.6% | 351 | 41.1% |

| Elevated triglycerides alone | 384 | 29.7% | 120 | 14.1% |

| Low HDL-C alone | 114 | 8.8% | 69 | 8.1% |

| Mixed dyslipidemiasb | 399 | 30.9% | 314 | 36.8% |

| Two dyslipidemias | 339 | 26.2% | 260 | 30.5% |

| Low HDL-C and/or elevated triglycerides | 897 | 69.4% | 503 | 58.9% |

| Low HDL-C and/or elevated triglycerides and elevated LDL-C | 310 | 24.0% | 262 | 30.7% |

| All three dyslipidemias | 60 | 4.6% | 54 | 6.3% |

Notes:

Without regard to other lipid parameters;

combinations of two or more dyslipidemias.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol.

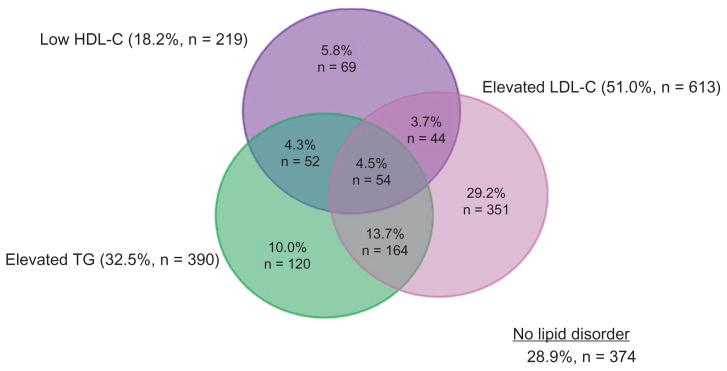

At least one dyslipidemia was present in 71.1% of high-risk subjects. Elevated LDL-C was the most prevalent dyslipidemia (51.0%), while dyslipidemias of elevated triglycerides and low HDL-C occurred in 32.5% and 18.2%, respectively, of high-risk patients (Figure 3). Among those at high risk with any dyslipidemia, 36.8% had mixed dyslipidemias (Table 3). Low HDL-C and/or elevated triglycerides occurred in 58.9% of high-risk patients with any dyslipidemias, compared to 41.1% for isolated elevated LDL-C (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of dyslipidemias in high-risk patients.*

Note: *N = 1201.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

All three dyslipidemias occurred in 4.6% of all patients and 6.3% of high-risk patients with any dyslipidemia (Table 3).

Variables associated with lipid goal attainment

A Framingham risk score >20% was the factor most strongly associated with attainment of lipid goal/normal level, with odds ratio (OR) values of 0.011, 0.210, and 0.564 for LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides, respectively (P < 0.01 for all effects; Table 4). A history of CVD/CHD was also associated with attainment of goals/normal level for all lipid parameters except triglycerides, for which the effect did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4.

Clinical factors associated with attainment of targets/normal levels for individual lipids and two or more lipids among the total population

| Predictor variablea | Odds ratio (95% CI) associated with attainment of lipid target/normal level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| LDL-C (N = 2521) | HDL-C (N = 2521) | Triglycerides (N = 2521) | ≥2 lipids* (N = 1822) | |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | NS | 1.04 (1.03–1.05)† | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)† | 1.05 (1.02–1.07)† |

| Gender (M/F) | 1.56 (1.23–1.98)† | 0.52 (0.38–0.70)† | NS | 0.58 (0.34–0.99)§ |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| 25–30 versus ≤25 | NS | 0.59 (0.42–0.83)‡ | 0.59 (0.46–0.74)† | 0.50 (0.26–0.95)§ |

| >30 versus ≤25 | NS | 0.47 (0.32–0.68)† | 0.32 (0.25–0.42)† | 0.35 (0.17–0.69)‡ |

| Diabetes (yes/no) | NS | 0.74 (0.56–0.98)§ | 0.76 (0.61–0.94)‡ | NS |

| Current smoker (yes/no) | 0.44 (0.31–0.61)† | NS | NS | NS |

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 0.72 (0.57–0.90)‡ | NS | 0.71 (0.58–0.86)† | NS |

| History of CVD/CHD and FRS | ||||

| FRS > 20% versus FRS ≤ 20% | 0.01 (0.01–0.02)† | 0.21 (0.14–0.32)† | 0.56 (0.39–0.81)‡ | 0.09 (0.03–0.31)† |

| History of CVD/CHD versus FRS ≤ 20% | 0.12 (0.09–0.15)† | 0.48 (0.36–0.64)† | NS | 0.39 (0.23–0.63)† |

Notes:

All models included: age, gender, body mass index, diabetes status, smoking status, hypertension status, history of CVD/CHD, FRS (>/<20%), year of statin prescription;

attainment of thresholds in ≥2 lipid parameters versus attainment of LDL-C target only;

P ≤ 0.001;

P ≤ 0.01;

P ≤ 0.05.

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FRS, Framingham Risk Score.

Several variables were significantly associated with normal level attainment for HDL-C and/or triglycerides but not LDL-C goal, or vice versa. Older age was associated with greater odds of attaining normal level for HDL-C and triglycerides but not the LDL-C goal. Similarly, a diagnosis of diabetes and BMI categories of 25–30 kg/m2 and >30 kg/m2 were associated with reduced odds of attaining normal levels for HDL-C and triglycerides but not the LDL-C goal. Conversely, being a current smoker reduced the odds of LDL-C goal attainment but not attainment of normal levels for HDL-C or triglycerides. Male gender increased the odds of attaining the LDL-C target but decreased the odds of attaining the normal level for HDL-C.

The odds of attaining goal/normal level for ≥2 lipid parameters followed the pattern for HDL-C and triglycerides for age, BMI categories, smoking status, Framingham risk score, and history of cardiovascular disease. Year of index statin prescription had no statistically significant association with any lipid goal attainment.

Comment

The proportion of patients meeting AFSSAPS criteria for high cardiovascular risk in this study (47.2%) was similar to the 51.2% in a previous study of mixed dyslipidemias in patients treated with lipid-modifying drugs in French general practice.29 The present study differs, however, in methodology and results for dyslipidemias. The previous study applied lipid thresholds defined in JES III rather than in the AFSSAPS guideline.29 The principal difference between the two guidelines is that AFSSAPS has less stringent targets for LDL-C for patients not at high risk (Table 1). In addition, patients in the earlier study were selected for being prescribed either a statin or fibrate, so that 67.1% used statin monotherapy and 31.8% used fibrate monotherapy. In the current study 92.7% of patients received statin monotherapy and none received fibrates. Possibly for these reasons, the proportions of patients with elevated LDL-C differed in the two studies: 73.2% in the previous study and 27.7% in the present study. The proportions of patients with low HDL-C and elevated triglycerides were similar in the two studies but the relative contributions differed. Dyslipidemias of HDL-C and/or triglycerides were present in 46.3% of patients with any dyslipidemia in the previous study versus 69.4% in the present study. Results for the high-risk group in the current study more closely resembled those in the previous study, possibly because the lipid thresholds for high-risk patients are nearly identical in the AFSSAPS and JES guidelines. Isolated LDL-C occurred in 41.1% of high-risk patients with any dyslipidemia in the current study versus 53.7% in the previous study. Corresponding values for dyslipidemias of HDL-C and/or triglycerides are 58.9% and 46.3%, respectively.

Results show that prevalence rates of dyslipidemia in France, as observed in this study, are lower than those seen throughout Europe and Canada. Compared to results seen in the Dyslipidemia International Study (DYSIS) (an epidemiologic multi-center, cross-sectional study of lipid profiles of 22,063 statin-treated outpatients in 11 European countries and Canada), French patients have a lower prevalence of low HDL-C (12.4% vs 26.3%), elevated LDL-C (27.7% vs 48.2%), and elevated triglycerides (28.7% vs 38.2%).41

Factors associated with lipid goal attainment have been reported in several cross-sectional studies of patients treated with lipid-modifying drugs in France.23,26,29 Dallongeville et al reported that increased waist circumference was associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving the triglyceride normal level of 150 mg/dL26 – equivalent to the relationship between BMI and attainment of a normal triglyceride level observed in the present study. In the study reported by Ferrieres et al, variables associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving the 2005 AFSSAPS target for LDL-C – smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, CHD, and increased risk of CVD – matched those in the present study (with the exception of diabetes).23 Applying JES III criteria, Van Ganse et al reported that each additional cardiovascular risk factor increased the occurrence of dyslipidemias of HDL-C and/or triglycerides (with normal LDL-C), the joint dyslipidemia of LDL-C and triglycerides (with normal HDL-C), and all three dyslipidemias.29 These results correspond to the finding in the current study that a Framingham risk score >20% was associated with a reduced likelihood of attaining targets/normal levels for ≥2 lipids.

Except for Framingham risk score and history of CVD/CHD, cardiovascular risk factors tended to be significantly associated either with attainment of normal levels for HDL-C and/or triglycerides but not LDL-C goal, or vice versa. This may be related to the fact that statins, which primarily affect LDL-C, were the only lipid-modifying drug used by 92.7% of patients, or it may be a reflection of the structure of the AFSSAPS guideline, in which risk factors escalate the target for LDL-C but not the normal levels for other lipids. Current smoking and hypertension are risk factors that trigger a more stringent LDL-C target in the AFSSAPS guideline, and this may explain their association with a reduced likelihood of attaining the LDL-C goal. However, other risk factors – diabetes and age – were not significantly associated with LDL-C goal attainment. A relationship between male gender and a higher rate of LDL-C goal attainment has been reported previously.40–42 The explanation for this is unclear, although it is possible that men either receive more aggressive treatment40 or are more adherent to statin regimens than are women.43,44 Not surprisingly, the pattern of risk factors associated with goal/normal level attainment for mixed dyslipidemias (interpreted as ≥2 lipids versus LDL-C alone) tended to follow the pattern for HDL-C and triglycerides – specifically for age, BMI categories, smoking status, Framingham risk score, and history of cardiovascular disease. Unfortunately, the electronic database did not include reliable information on dietary behaviors and exercise, which can also impact goal/normal lipid level attainment. Additional studies are needed to assess the differential impact of these factors, controlling for the abovementioned characteristics, on the prevalence of dyslipidemias despite lipid-modifying treatment.

Conclusion

By applying French national guidelines, we observed at least one dyslipidemia to be present among more than half (50.8%) of these primary care patients treated with statins. About one-third (30.9%) of patients with any dyslipidemia had mixed dyslipidemias, with low HDL-C and/or elevated triglycerides occurring in more than two-thirds (69.4%) of patients with any dyslipidemia, compared to 30.6% for isolated elevated LDL-C.

According to most guidelines, elevated LDL-C is one of, if not the primary, treatment target for reducing cardiovascular risk.1–3 The persistence of elevated LDL-C, even among patients already on lipid-modifying therapy, and particularly among patients at high cardiovascular risk, suggests that current statin treatment (with which >90% of patients in this sample were treated) is not adequate. In light of evidence showing that low HDL-C and elevated TGs are also associated with increased risk of CHD,4–9 along with our observations of the prevalence of mixed dyslipidemias both before and after lipid modifying therapies, suggests that patients may benefit from the addition of therapies targeting HDL-C and/or triglycerides.

Acknowledgment

Medical writing assistance was provided by Julia Vishnevetsky in collaboration with SCRIBCO.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Funding for this study was provided by Merck and Co, Inc.

References

- 1.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110(2):227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary: Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (Constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur Heart J. 2007;28(19):2375–2414. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third Joint Task Force of European and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(17):1601–1610. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannel WB. High-density lipoproteins: epidemiologic profile and risks of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52(4):9B–12B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90649-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977;62(5):707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldbourt U, Medalie JH. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and incidence of coronary heart disease – the Israeli Ischemic Heart Disease Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(3):296–308. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assmann G, Schulte H. Relation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides to incidence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (the PROCAM experience). Prospective Cardiovascular Munster study. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(7):733–737. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90550-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacks FM, Tonkin AM, Shepherd J, et al. Effect of pravastatin on coronary disease events in subgroups defined by coronary risk factors: the Prospective Pravastatin Pooling Project. Circulation. 2000;102(16):1893–1900. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, et al. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1301–1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison A, Hokanson JE. The independent relationship between triglycerides and coronary heart disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5(1):89–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birjmohun RS, Hutten BA, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. Efficacy and safety of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol-increasing compounds: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(2):185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards JE, Moore RA. Statins in hypercholesterolaemia: a dose-specific meta-analysis of lipid changes in randomised, double blind trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2003;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326(7404):1423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson MH, McKenney JM, Shear CL, Revkin JH. Efficacy and safety of torcetrapib, a novel cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor, in individuals with below-average high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(9):1774–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oram JF. Tangier disease and ABCA1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1529(1–3):321–330. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benlian P, Etienne J, de Gennes JL, et al. Homozygous deletion of exon 9 causes lipoprotein lipase deficiency: possible intron-Alu recombination. J Lipid Res. 1995;36(2):356–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benlian P, De Gennes JL, Foubert L, Zhang H, Gagne SE, Hayden M. Premature atherosclerosis in patients with familial chylomicronemia caused by mutations in the lipoprotein lipase gene. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(12):848–854. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hokanson JE. Functional variants in the lipoprotein lipase gene and risk cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10(5):393–399. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittrup HH, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Lipoprotein lipase mutations, plasma lipids and lipoproteins, and risk of ischemic heart disease. A meta-analysis. Circulation. 1999;99(22):2901–2907. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.22.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorn JA, Needham EW, Mattu RK, Stocks J, Galton DJ. The Ser447- Ter mutation of the lipoprotein lipase gene relates to variability of serum lipid and lipoprotein levels in monozygotic twins. J Lipid Res. 1998;39(2):437–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gagne SE, Larson MG, Pimstone SN, et al. A common truncation variant of lipoprotein lipase (Ser447X) confers protection against coronary heart disease: the Framingham Offspring Study. Clin Genet. 1999;55(6):450–454. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Ganse E, Souchet T, Laforest L, et al. Ineffectiveness of lipid-lowering therapy in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59(4):456–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrieres J, Gousse ET, Fabry C, Hermans MP. Assessment of lipid-lowering treatment in France–the CEPHEUS study. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101(9):557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Ganse E, Laforest L, Alemao E, Davies G, Gutkin S, Yin D. Lipid- modifying therapy and attainment of cholesterol goals in Europe: the Return on Expenditure Achieved for Lipid Therapy (REALITY) study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(9):1389–1399. doi: 10.1185/030079905X59139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupuy AM, Carriere I, Scali J, et al. Lipid levels and cardiovascular risk in elderly women: a general population study of the effects of hormonal treatment and lipid-lowering agents. Climacteric. 2008;11(1):74–83. doi: 10.1080/13697130701877108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dallongeville J, Bringer J, Bruckert E, et al. Abdominal obesity is associated with ineffective control of cardiovascular risk factors in primary care in France. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34(6 Pt 1):606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolovou GD, Anagnostopoulou KK, Damaskos DS, et al. Gender differences in the lipid profile of dyslipidemic subjects. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(2):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozano JV, Pallares V, Cea-Calvo L, et al. Serum lipid profiles and their relationship to cardiovascular disease in the elderly: the PREV-ICTUS study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(3):659–670. doi: 10.1185/030079908X273372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Ganse E, Laforest L, Burke T, Phatak H, Souchet T. Mixed dyslipidemia among patients using lipid-lowering therapy in French general practice: an observational study. Clin Ther. 2007;29(8):1671–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: third joint task force of European and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of eight societies and by invited experts) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003;10(4):S1–10. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000087913.96265.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruckert E, Baccara-Dinet M, McCoy F, Chapman J. High prevalence of low HDL-cholesterol in a pan-European survey of 8545 dyslipidaemic patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(12):1927–1934. doi: 10.1185/030079905X74871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé. Prise en charge thérapeutique du patient dyslipidémique. Saint-Denis Cedex, France: AFSSPS; 2005. French. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laforest L, Moulin P, Souchet T, et al. Correlates of LDL-cholesterol goal attainment in patients under lipid lowering therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2008;199(2):368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Ganse E, Souchet T, Laforest L, et al. Long-term achievement of the therapeutic objectives of lipid-lowering agents in primary prevention patients and cardiovascular outcomes: an observational study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chassany O, Le-Jeunne P, Duracinsky M, Schwalm MS, Mathieu M. Discrepancies between patient-reported outcomes and clinician-reported outcomes in chronic venous disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Value Health. 2006;9(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amouyel P, Lamarque H, Gayet JL. Treatment with statins in general medicine: dosage and effectiveness. Results of the observational study STATIMED. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2005;98(12):1206–1211. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graesslin O, Hoffet M, Barjot P, et al. Preliminary results from the OPNI observatory: long-term follow-up of a cohort of women using the progestagen contraceptive implant Implanon. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005;33(5):315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.022. French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouee S, Charlemagne A, Fagnani F, et al. Changes in osteoarthritis management by general practitioners in the COX2-inhibitor era-concomitant gastroprotective therapy. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71(3):214–220. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(03)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putzer G, Roetzheim R, Ramirez AM, Sneed K, Brownlee HJ, Jr, Campbell RJ. Compliance with recommendations for lipid management among patients with type 2 diabetes in an academic family practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(2):101–107. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parris ES, Lawrence DB, Mohn LA, Long LB. Adherence to statin therapy and LDL cholesterol goal attainment by patients with diabetes and dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):595–599. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz JS, O’Donnell JC, McDonough KL, Sasane R, Meyer J. Determinants of compliance with statin therapy and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in a managed care population. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(5):306–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]