Abstract

Although the barriers to couples’ help seeking can be daunting, to date there is only a small body of literature addressing the factors that motivate couples to seek help. This study examined the association between attitudes towards relationship help seeking and relationship help seeking behaviors, as well as the association between marital quality and help seeking. This study was completed in the context of the Marriage Checkup, a brief intervention designed to reduce the barriers to help seeking. Results indicated that help seeking attitudes and behaviors were not related in couples, and that wives’ marital quality was negatively associated with both wives’ and husbands’ help seeking. Husbands’ marital quality was not associated with husbands’ help seeking. Overall, this suggests that the process of couples’ help seeking is distinct from that of individuals, and seems to be driven primarily by the female partner. Further implications for theory and treatment are discussed.

Keywords: Checkup, Couples, Help Seeking, Marriage, Attitudes

Although the barriers to couples’ help seeking may be even more daunting than the barriers to individual help seeking, to date there is only a small body of literature addressing this topic (e.g. Doss, Simpson, & Christensen, 2004). Consequently, there are a number of questions remaining regarding the potential differences between couples’ help seeking and individual help seeking as well as regarding the relationship variables that may be associated with couples’ help seeking. Couples’ help seeking can range from simply buying a self-help book or looking up relationship information online, to discussing relationship issues with friends/family, seeking out a marriage retreat, or participating in a full course of couples’ therapy. Partners may also vary in their attitudes about seeking help for the relationship from beliefs that relationship issues should be kept entirely private to beliefs that seeking outside help is easy and valuable.

Existing studies have revealed many of the variables associated with individual help seeking, but relationship scientists have only recently begun to seriously investigate the same phenomenon in couples. Couples present a unique challenge when it comes to help seeking, most simply because both members of the couple have to agree to seek help and because either partner can prevent effective help seeking. Studies of couples’ help seeking could specifically provide a better understanding of the factors associated with couples leaning towards or against seeking help, and to understanding the unique ways in which each partners’ beliefs about help seeking might influence the other partner and the couple’s outcomes. Studying what influences couples to look for outside help might help to further lower barriers to couples’ help seeking, which can in turn help relieve the associated poorer mental, physical, and child health outcomes (Amato & Booth, 1991; Whisman & Uebelacker, 2006).

The current study specifically examined couples seeking a Marriage Checkup (MC) rather than traditional tertiary couples therapy because the MC was designed, in part, to actively facilitate couples’ help seeking. Although there are similarities between the Marriage Checkup and more traditional forms of treatment, the MC has been shown to attract a broader group of couples, ranging from satisfied to “at-risk” to quite distressed (Morrill, Fleming, Harp, Sollenberger, Darling, & Cordova, in press). Our goal in this paper is to increase our understanding of couples’ help seeking in the context of the ongoing Marriage Checkup project by examining the relationships between wives’ and husbands’ attitudes toward help seeking, marital quality/distress, and their actual help seeking behavior prior to enrolling in the Marriage Checkup. In particular, we aim to investigate aspects of couples’ help seeking which have been suggested, but not yet investigated in the existing literature. For example, research has yet to determine the relationship between attitudes and behaviors in couples’ help seeking, and has only begun to examine partners’ influences on each other in the domain of help seeking.

What motivates couples to seek help and to make changes? Most broadly, researchers and practitioners alike have come to understand the process of change through the Stages of Change model (Prochaska &DiClemente, 1984). This model suggests that individuals move through a series of 5 stages: Precontemplation (no intention to change, little to no recognition of a problem), Contemplation (aware of a problem, considering change but without a firm commitment), Preparation (beginning to make small behavioral change, full intention to take “effective action” in the next month), Action (full and successful behavioral change for a time period ranging from one day to six months), and Maintenance (working to prevent relapse and solidify gains; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). These authors also discuss relapse, as a significant number of people attempting to change cycle through these stages several times.

Within this framework, it is theorized that people move through the stages based on ten different processes of change. People in the early stages rely more heavily on processes such as consciousness raising (beginning to be challenged with the evidence that one has a problem) and environmental reevaluation (evaluating how one’s actions affect others and the surroundings), while people in later stages rely more on processes such as self-liberation (telling oneself that one has the ability to change) and on helping relationships (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992).

More specifically, other research has shown that in individuals, a positive attitude towards a behavior leads to a positive intention to complete a behavior, which then leads to actually completing the behavior (Azjen & Fishbein, 1980; Bringle & Byers, 1997). Similarly, this approach suggests that a negative attitude leads to a lack of intention to complete a behavior, and thus a failure to complete the behavior (Azjen & Fishbein, 1980). Taken together, these theories suggest that people change when they begin to recognize the consequences of their actions, and when they have a strong intention to do so, which has likely stemmed from their attitude towards the action.

What does this mean for couples? Although these patterns have been strongly established with individuals, there may be differences in what motivates help seeking in individuals vs. in couples. Practically, there may be greater barriers to couples’ help seeking, such as the need for both partners to be willing to obtain relationship help, or the difficulty of finding appropriate childcare and time off to be able to spend time focusing on the relationship. Another major factor that may affect couples’ help seeking is the interplay of gender differences in couples’ attempts to seek help. Research has suggested that the association between attitudes and behaviors may not hold as strongly in men (Good, Dell, & Mintz, 1989), and more broadly, there may also be significant differences in help seeking between men and women in general, which could affect seeking help together (Perry, Turner, & Sterk, 1992; Surrey, 1985). For example, studies have repeatedly shown that women are more likely to seek help than men overall (Mackenzie, Gekoski, & Know, 2006), and have indicated that men tend to report greater barriers to help seeking than women do, particularly in the areas of fear of stigma, mistrust of the health-care system, and negative attitudes towards receiving treatment (Ojeda & Bergstresser, 2008). This potential individual reluctance to seek help can be particularly problematic for couples with marital health concerns, given that both partners have to be willing for the couple to enter treatment.

There is also growing support for a theory that suggests that the female partner may be the most influential in the pursuit of help seeking. One line of research has suggested that women serve as the “relationship barometer,” meaning that they are the partner who is more in tune with the couple’s level of relationship functioning (Faulkner, Davey, & Davey, 2005). Further research has suggested that men’s relationship quality is reduced by the “presence of negative,” while women’s marital quality diminishes in the “absence of positive” (Carroll, Badger, & Yang, 2006). This pattern may lead women to notice relationship decline earlier, and to be more negatively affected as the couple moves closer to the distressed range.

Recent studies have begun to examine some of the variables that appear to be associated with couples’ help seeking. For example, lower levels of intimacy have been shown to be correlated with individual psychological help seeking, and may be correlated with couples’ help seeking, as well (Chamberlaine, Barnes, Waring, Wodd, & Fry, 1989). Two studies have suggested that specific marital health issues such as problems with communication, affection, marital satisfaction, and concerns about divorce are associated with couples’ help seeking (Doss, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2009; Doss, Simpson, & Christensen, 2004). Although informative, these studies have focused exclusively on couples seeking therapy as a tertiary intervention, which represent a small subsection of the population of couples at risk for marital health deterioration.

Research has also examined the differences in couples that do or do not attend marital and pre-marital education programs (Duncan, Holman & Yang, 2007). These programs (e.g. PREP, CARE, B.E.S.T. Families) are similar in nature to the Marriage Checkup, which is designed as both prevention and early intervention. Duncan and colleagues (2007) suggested that marital education programs are effective, but that relatively few of the targeted couples participate in these types of programs, and that many education participants are primarily coming from religiously affiliated groups. This research found that attendance was more likely when partners reported more problems in the marriage and when both wives and husbands highly valued the institution of marriage (Duncan, Holman, & Yang, 2007). Research on high risk vs. low risk couple attendance again found that most couples who attended marital education programs were more religious and less likely to cohabit, indicating that high-risk couples may be less likely to attend (Halford, O’Donell, Lizzio, & Wilson, 2006). However, further research in this area suggested that marital education is effective with high-risk couples (compared to both low-risk and control) when those couples do attend (Halford, Sanders, & Behrens, 2001).

Similar studies have investigated other characteristics of attending and non-attending husbands and wives, indicating that attendance in marital education programs is more likely among Caucasians, men with higher income, and women with higher education (Stanley, Amato, Johnson, & Markman, 2006; Sullivan & Bradbury, 1997). Others have suggested that women who did not attend marital education had higher self-esteem, and that men who did not attend were more fearful of the content of the intervention (Roberts & Morris, 1998). Both nonparticipating partners in this case were shown to have reported more significant barriers to treatment than did participators, and both partners were shown to have been concerned about how “therapy-like” the intervention would be (Roberts & Morris, 1998).

Purpose

The Marriage Checkup study served as the context for examining couples’ help seeking attitudes and behaviors in a sample of couples who represent a broader range of marital distress scores than do tertiary help seeking couples (Cordova, Scott, Dorian, Mirgain, Yaeger, & Groot, 2005) and yet who are still willing to take steps towards improving their marital health. The Marriage Checkup was designed to lower many of the traditional barriers to treatment seeking such as concerns about (1) having to be “distressed enough” to seek help, (2) the length of traditional treatment, and (3) the cost and inconvenience of traditional treatment. The MC is targeted at the general population of married couples, is only 2 sessions in length, and is specifically described as “not therapy.”

The Marriage Checkup is informed by Prochaska and DiClemente’s Stages of Change Model (described above; 1984). Through the use of both Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and Integrative Behavioral Couples Therapy techniques (Cordova, Jacobson & Christensen, 1998), the goal of the Marriage Checkup is to encourage couples to become more motivated in the service of their marital health and to foster a sense of greater acceptance and deeper intimacy. Fundamentally the goal is to connect and activate couples to move in the direction of more regularly working to improve their marital health.

Couples seeking a Marriage Checkup represent the entire range of marital health, from healthy to severely unhealthy, as well as a broad range of relationship length from less than one month through 56 years (Cordova et al., 2005, Morrill et al., in press). Marriage Checkup couples also fall along the entire continuum of the Stages of Change, with some couples who feel like they have no problems (precontemplative) as well as some couples who seem to see the MC as a form of action. Other couples in the MC fall in the middle range (contemplative) and have begun to acknowledge that they have concerns, but still describe the MC as “interesting” rather than as a true form of help seeking (Morrill et al., in press). The Marriage Checkup attracts some couples who might seek tertiary treatment, who are typically quite distressed, and some couples who are seeking marital education, who are typically in the earlier stages of marriage.

However, one of the foundational assumptions of the Marriage Checkup project is that couples will not seek tertiary couples therapy until they are openly distressed and that prior to reaching that tipping point couples will not seek the help of professionals in a tertiary treatment setting. The Marriage Checkup is designed to attract couples who would not otherwise seek professional help with their relationship issues by removing the “treatment” barrier and creating a setting in which couples who are not openly distressed (or who are otherwise biased against “treatment”) can address existing relationship concerns. In other words, couples will seek a Marriage Checkup even when they are not “distressed enough” to seek tertiary treatment and/or are biased against couples “therapy,” because they are motivated by emergent levels of distress that are otherwise insufficient to motivate seeking a full course of couples therapy. One of the assumptions within this rationale is that couples are motivated by their relationship health concerns (i.e., relationship distress) to seek help, even when those concerns have not reached the threshold necessary to motivate tertiary treatment seeking. Thus, our first hypothesis is that couples are motivated by relationship distress to engage in multiple forms of help seeking. The measure employed in the current study allows us to assess the range of specific help seeking behaviors engaged in by partners prior to signing up for the Marriage Checkup (e.g., seeking help online or reading self-help books or seeking therapy).

At the same time, we suspect that this motivation is complicated by a masculinity bias against help seeking. There is strong evidence in the existing literature that men on average are more negatively biased against all forms of help seeking and that women on average are significantly more likely to seek all kinds of help (Mackenzie, Gekoski, & Know, 2006; Ojeda & Bergstresser, 2008). In other words, we suspect that in most cases, seeking relationship-level help is motivated primarily by wives’ distress rather than husbands’ distress. Our second hypothesis is that in this population, while both husbands’ and wives’ relationship quality will be negatively associated with their own help seeking, that wives’ marital quality will also be negatively associated with husbands’ help seeking.

Finally, although there is substantial evidence in the treatment seeking literature demonstrating a robust association between attitudes toward treatment seeking and actual treatment seeking, we suspect this association likely breaks down with the shift from individual-level treatment seeking to relationship-level treatment seeking. Considering the potential barriers and gender differences affecting couples’ help seeking, our third hypothesis is that in a sample of couple help seekers, the association between attitudes toward relationship help seeking and actual relationship help seeking will be substantially smaller than that previously demonstrated in the individual help seeking literature.

METHODS

Participants

Participants in this study were 210 heterosexual married couples who were recruited for the Marriage Checkup Project (MC). This project is an on-going, longitudinal study of the short and long-term marital health effects of the Marriage Checkup. The MC is designed to be the marital health equivalent of the annual physical health checkup and is designed as a two-session therapeutic assessment and motivational feedback intervention. The MC consists of a battery of pre-session marital health questionnaires, a two-hour therapeutic assessment session, and a two-hour motivational feedback session. Treatment outcome data collection for the current trial of the Marriage Checkup is ongoing, however details of the MC format and results of past studies can be found in Cordova et al., 2005, and Cordova, Warren, & Gee, 2001. In the current study, participants were given a battery of questionnaires, including those listed below, prior to being randomly assigned to treatment and control conditions, and then again at multiple time points over the following 2 years. Participants received paper copies of questionnaires, along with separate return envelopes, and were asked to complete the packets as soon as was possible. In the current study, only data from the pre-intervention assessment were used, in order to assess help seeking prior to intervention.

Because participants were heterosexual couples, the total of 420 participants were evenly split between genders. The majority of the sample was non-Hispanic Caucasian (93.1%), and also included African-Americans (2.4%), Asians (2.4%), Hispanics (1.8%), and American Indians (.4%). The average age for this sample was 46.58 years (SD = 10.65), and the average length of marriage was 16.60 years (SD = 11.54). The average annual income was between $50,000 and $75,000, and the average level of education was 15.74 years (SD = 2.85). Within the sample, 85.7% of participants had at least one child that they were currently raising in the home. Participants were recruited for this study through the use of both print and electronic classified ads, local news coverage, and word-of-mouth. Subjects were paid at each of the assessment time points in increasing amounts beginning with $50 for the first time point and concluding with $100 for the final time point.

Measures

The Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help – Marital Therapy Questionnaire (ASPPH-MT; Cordova, 2007)

The ASPPH-MT was reworded from the original Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help Measure (Fischer & Turner, 1970) to focus on relationship-level help seeking. It is a 28-item self-report measure of a person’s positive or negative attitude towards marital help seeking. For example, the item on the original scale, “I would feel uneasy going to a Psychiatrist because of what some people would think” was rephrased as, “I would be uneasy going to a marriage counselor because of what people would think.” Respondents rated their level of agreement on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 4 (agree), with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes. The internal reliability for this measure in this study was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

The Relationship Help Seeking Measure (RHSM; Cordova & Gee, 2001)

The RHSM consists of 11 questions that ask participants to indicate simple participation or non-participation in various relationship help seeking activities, such as seeking information online, in books, from family or community members, seeking professional help or participating in counseling, etc. Scores were summed to indicate amount of participation in relationship help seeking.

The Quality Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983)

The QMI is a 6-item measure that assesses a partner’s evaluation of the quality of her or his marriage. In this study, only the first five of the items in the measure were used, as they are each ranked on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Examples of these items include, “we have a good relationship,” and “my relationship with my partner makes me happy.” The measure has been extensively validated and correlates highly with other measures of marital health, such as the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). In the current study, the internal reliability of the measure was very high (Cronbach’s α = 0.97).

Data analysis plan

The stated hypotheses were tested using 2 separate structural equation models as a form of the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Model 1 examined the association between husbands’ and wives’ attitudes towards relationship help seeking (labeled Attitudes) and actual relationship help seeking behaviors (labeled Help Seeking). Model 2 examined the relationship between husbands’ and wives’ marital quality (and conversely distress) and actual relationship help seeking behaviors.

RESULTS

Relevant descriptive statistics, as well as correlations among measures for both wives and husbands, are presented in Table 1. Both of the models below were analyzed in structural equation models with AMOS 17. Model fit was assessed by three major measure of goodness of fit (Meyers, Gamst, & Guarino, 2006): the model chi-square statistic (good fit indicated by a nonsignificant test, p >.05), the normed fit index (NFI; good fit indicated by a value of .95 of greater), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; good fit indicated by a value less than .08).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Measures for Wives (W) and Husbands (H)

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. W Attitudes | 3.43 | 0.34 | -- | .26** | −.21* | −.10 | .13 | .03 |

| 2. H Attitudes | 3.18 | 0.36 | -- | −.03 | .12 | −.03 | .09 | |

| 3. W Quality | 5.76 | 1.39 | -- | .56** | −.50** | −.32** | ||

| 4. H Quality | 5.80 | 1.34 | -- | −.35** | −.17* | |||

| 5. W Help Seeking | 1.06 | 1.51 | -- | .42** | ||||

| 6. H Help Seeking | 0.90 | 1.55 | -- |

p< .05,

p< .01

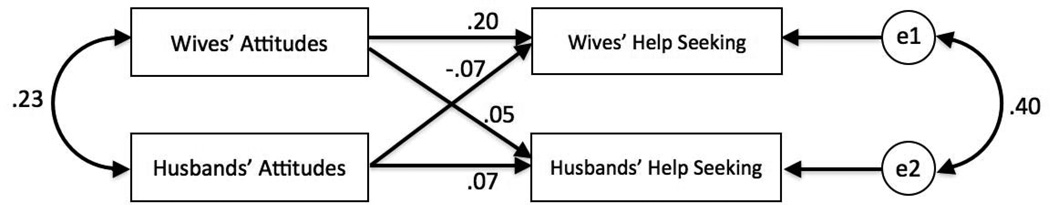

Model 1

To examine actor effects in the association between relationship help seeking attitudes and relationship help seeking behaviors, paths were specified from wives’ attitudes to wives’ help seeking, and from husbands’ attitudes to husbands’ help seeking (see Figure 1). To examine partner effects, paths were specified from wives’ attitudes to husbands’ help seeking, and from husbands’ attitudes to wives’ help seeking. Because husbands and wives typically share backgrounds and experiences, data collected from both partners cannot be considered independent. To account for this issue, the exogenous variables were allowed to correlate, and error terms were also allowed to correlate.

Figure 1.

The Actor Partner Interdependence Model for Attitudes and Help Seeking. Single headed lines represent predictive paths, and double headed lines represent correlations. None of the paths shown are statistically significant (p > .05).

Model 1 provided a moderate fit to the data (χ2 (1) = 1.885, p > .05, NFI = .95, RMSEA = .08). However, none of the individual paths approached significance, indicating that further specification would not likely improve the fit of the overall model. The overall model accounted for only 4% of the variance in wives’ help seeking, and only 1% of the variance in husbands’ help seeking. Notably, the correlations between wives’ attitudes and help seeking and husbands’ attitudes and help seeking were also small and non-significant (p > .05). This provides preliminary evidence for the hypothesis that the relationship between attitudes and behaviors is not as strong in couples’ help seeking as it is in individual help seeking.

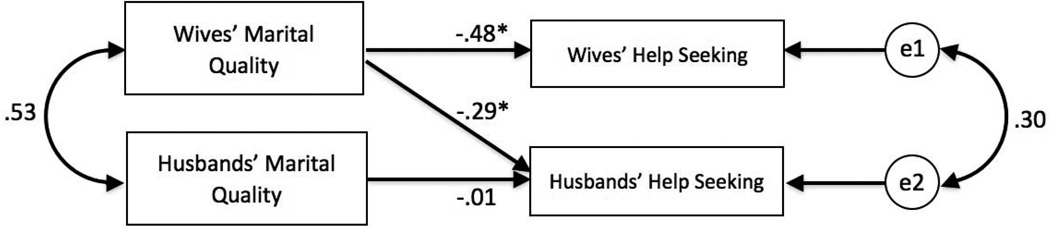

Model 2

Model 2 was originally tested with paths specified for actor effects (from wives’ marital quality to wives’ help seeking and from husbands’ marital quality to husbands’ help seeking) and for partner effects (from wives’ marital quality to husbands’ help seeking and from husbands’ marital quality to wives’ help seeking). Model 2 also accounted for partner non-independence by allowing exogenous variables and error terms to correlate. This version of the model was not an adequate fit for the data (χ2(1) = 152.26, p < .05, NFI ≈ 0,RMSEA = .99), and so the model was respecified with the removal of the path from husbands’ marital quality to wives’ help seeking. This decision was made based on the evidence suggesting that men are less likely to seek help than women and that women are more attuned to the problems in the relationship than are men (Faulkner, Davey, & Davey, 2005; Mackenzie, Gekoski, & Know, 2006).

The second version of the model (see Figure 2), was a good fit for the data (χ2 (1) = 1.00, p > .05, NFI = .99, RMSEA = .004). Because the overall model was significant, parameter estimates could then be examined. For the actor effects, the path from wives’ marital quality to wives’ help seeking was significant, while the path from husbands’ marital quality to husbands’ help seeking was not. For the partner effects, the path from wives’ marital quality to husbands’ help seeking was significant. The R2 values indicated that the model accounted for 23% of the variance in wives’ help seeking, and 10% of the variance in husbands’ help seeking. This does seem to suggest that marital quality is negatively associated with help seeking, and that wives’ levels of quality/distress are important factors in the move to seek relationship help.

Figure 2.

The Actor Partner Interdependence Model for Marital Quality and Help Seeking. Single headed lines represent predictive paths, and double headed lines represent correlations. *p < .01

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to begin to create an understanding of the factors that affect couples’ help seeking behaviors, ranging from buying a self-help book to entering therapy. The current results lend support for our hypothesis that suggested that attitudes towards relationship help seeking and actual relationship help seeking would be less clearly related in couples than in individuals. Within Model 1, no actor effects (paths from wives’ attitudes to wives’ help seeking and from husbands’ attitudes to husbands’ help seeking) were significant, suggesting that each partner’s attitudes towards relationship help seeking were not associated with their own behaviors. Additionally, no partner effects (paths from wives’ attitudes to husbands’ help seeking and vice versa) were significant, suggesting that each partner’s attitudes were not associated with their partner’s behaviors.

Interestingly, this lack of association for couple members is different from the pattern repeatedly and consistently found in individual help seeking research. The difference between individual help seeking and couple help seeking may be due to the unique and more complex barriers to help seeking that face a couple compared to an individual seeking help. In couples, for example, one partner may be unwilling to seek treatment and can therefore “veto” treatment seeking as an option or in other ways undermine attempts to treatment seek. Additionally, partners may find it difficult to find the time to seek treatment together, due to busy schedules or lack of childcare options. This finding suggests that whereas individuals may be encouraged to seek help through the influence of their attitudes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), couples may need to be motivated though other pathways.

Another possible reason for the lack of a relationship between attitudes and actions in couples may be a perception that seeking couples therapy is dangerous to the relationship itself and that even admitting there are serious relationship concerns could precipitate the end of the relationship. Although there are certainly barriers to seeking individual treatment, a partner who is considering seeking some form of assistance for couples’ issues may perceive added barriers, such as the threat of being blamed for mistakes or actions in the past or even the threat of losing the relationship entirely. For example, several partners in this study suggested that they worried that a therapist would “always take [the other partner’s] side,” or that broaching these topics would “stir up old issues” that might cause more problems than were currently occurring. Some partners even recalled that they had seen friends who had attempted couples therapy and then gotten a divorce.

One of the major goals of the Marriage Checkup is to help reduce traditional barriers to seeking relationship help, so that the idea of seeking help for a relationship feels less like the relationship is on the line and more like a safe and routine maintenance activity. In particular, the Marriage Checkup is designed to be seen as different from tertiary treatment, which many couples see as requiring the admission of serious relationship problems. In the context of a Checkup, couples can seek help without having to more explicitly discuss with each other the possibility that there is a problem (Morrill et al., in press). When asked about seeking a Checkup, many participants noted that therapy seemed too intimidating and that thinking of marital maintenance as similar to vehicle maintenance made seeking help less threatening and more palatable.

Results for this study lend partial support for our hypotheses which suggested that couples are motivated by relationship distress to engage in multiple forms of help seeking, such that a) husbands’ and wives’ help seeking would both be negatively associated with their own level of marital quality (i.e. that a lower quality marriage would produce greater help seeking), and that b) wives’ marital quality would be negatively associated with husbands’ help seeking. Model 2 was significant overall, and accounted for a moderate amount of variance in wives’ help seeking, as well as a modest amount of variance in husbands’ help seeking. Only one actor affect, the path from wives’ marital quality to wives’ help seeking, was significant, while the path from husbands’ marital quality to husbands’ help seeking was not significant. The partner effect, the path from wives’ marital quality to husbands’ help seeking, was also significant.

These results indicate that wives’ help seeking is significantly affected by their own assessment of the quality of the marriage, and that husbands’ behaviors seem to be affected by wives’ assessment of the relationship more so than their own. This lends credibility to the theory that wives tend to function as a “relationship barometer” (Faulkner, Davey, & Davey, 2005), and are the partner who is often more aware of the level of relationship functioning (Carroll, Badger, & Yang, 2006). This finding is also consistent with evidence that men are typically more reluctant to participate in help-seeking activities (Ojeda & Bergstresser 2008). These results further suggest that it may be possible for a couple to seek help or to be encouraged to seek help with only one partner fully on board. It appears that wives are more often the motivating partner, and while this may mean that there is a greater likelihood of couples coming in for treatment in general, and for a Marriage Checkup specifically, at the behest of one partner, it may additionally mean that one partner may be present in part against his wishes. Although now in treatment, this more reluctant partner may present rapport and engagement challenges to the treating clinician.

Additionally, the current findings add support to the assumption that even subclinical levels of distress are motivating toward help seeking, but that in the absence of interventions like the Marriage Checkup, these couples have few places to go with their concerns. Providing professional help for these couples at these subclinical levels of distress has the potential to prevent severe distress and deterioration in the same way that other health checkups do.

Thinking globally, these findings may suggest that the process of change in relationships is slightly different than the process of change for individuals. Although couples likely go through the same stages, it seems that there may be a more complex interaction of each of the individual’s stages that add up to the couple’s combined readiness to change. In this case, it seems that the wife may move through the Stages of Change (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992) earlier than does the husband. Also, while the wife may use typically early processes of change (e.g. becoming aware of marital problems and their effect on the environment), the husband’s processes seem to be, in part, reliant on her processes. This combination of stage progress may potentially leave each partner somewhat unhappy. For women, who typically have more positive attitudes towards help seeking and more attention to the need for help seeking, the man’s reluctance to seek help may delay her from getting help when she feels like it is necessary. For men, who typically have poorer attitudes towards help seeking and appear to be less attuned to the problems of the relationship, the woman’s encouragement to seek help may seem unnecessary.

Additionally, in concurrence with previous literature, these results suggest that there may be gender differences in the factors that are related to the predictors of help seeking actions for husbands and for wives. There are several possible reasons for these differences, which can be drawn from several theoretical backgrounds. For example, there seem to be differences in men’s and women’s comfort with emotional expression, in that women are typically more willing to show emotions, are more open to personal disclosure, and have a higher threshold for personal discomfort, which allows them to be more comfortable with the types of events that they expect will happen in treatment (Wolcott, 1986).

There also may be more deeply ingrained patterns of interaction that influence women to be more attentive to the need for seeking help. One possible explanation is that women are more accustomed to being cooperative rather than competitive with others (Perry, Turner, & Sterk, 1992), which might prepare them to be more willing to admit weaknesses, to work more with others, and to be more open to working on personal issues in the service of improving the relationship. For men, who have been historically raised to be more competitive, this trend may encourage them to hide weakness to try to continue to appear in control. Additionally, some research has suggested that women’s sense of self is more intimately tied to their close relationships (Surrey, 1985), which might influence them to be more invested in the quality and longevity of their important relationships. Similar research also suggests that men’s sense of self is more tied to their status and feelings of power, which would likely place their focus outside of the relationship (Perry, Turner, & Sterk, 1992).

Our findings also indicate that husbands’ relationship help seeking may be partly a product of their wives’ assessment of the relationship rather than of their own. In contrast to the patterns shown by women, men may be less responsive to the need for help when the relationship is distressed because they would rather keep the issue private without bringing their vulnerabilities to light, or because they are more uncomfortable with the emotional expression involved with treatment (Bringle & Byers, 1997; Perry, Turner, & Sterk, 1992). Notably, research has shown that men are no less able than women to label and discuss their thoughts and emotions, rather it appears that they are less inclined to do so (Judd, Komiti, & Jackson, 2008).

The results of this study imply that wives are more inclined to seek help when they are experiencing marital problems than are husbands. This suggests that it may be especially important for treatment providers to actively engage husbands early in the course of treatment, as they may in some cases feel that they have been brought to therapy against their will and contrary to their negative attitudes about help seeking. Further psycho-education may be beneficial for husbands who have less positive attitudes to help them better understand the health consequences of marital distress. These results further imply that it may be useful to assess why couples have sought treatment, since it appears likely that husbands and wives are seeking help with different feelings about treatment and different areas of concern.

In considering these results, it seems that the currently available forms of couples’ resources and treatment are in some way unappealing to many men. While there may be some utility to helping men better understand the benefits of couples’ treatment, it will also likely become necessary to adapt couples resources to better appeal to the needs of men. Although this may be difficult considering men’s concerns about the stigma surrounding many forms of treatment, future research might focus on learning more about men’s concerns about seeking couples’ treatment and on men’s perceptions of couples’ help seeking, in order to shape future resources in a more appealing manner.

A limitation of this study was a lack of diversity in the sample. Although our sample is similar to those in previous studies (e.g. Doss, Simpson, & Christensen, 2004), with mostly Caucasian participants who had a high median income, this lack of diversity limits generalizability. Also, this study was cross-sectional in nature, which did not allow for the examination of couples help seeking over time, and was completed entirely using self-report questionnaires. Because only self-report measures were used, common method bias is a potential issue. However, since many of the variables were not significantly correlated (see Table 1), this is not likely an issue in this study (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003).

One possible concern that might arise is that participants who are seeking help may be coming to the MC for the research payments. This is a common issue with randomized controlled studies, which often necessitate payment to keep participants motivated to continue. In this study, the amount of effort required by participants likely negates an overly monetarily - based participation in the study. Research has shown that monetary incentives only tend to influence quality of responses when payment is dependent upon the content or success rate of those responses (Camerer & Hograth, 1999). Another important factor to consider is that this was a study of couples specifically seeking a Marriage Checkup. This particular group of couples was not seeking traditional therapy but was seeking a less intimidating form of external help in a research setting, and thus may represent a somewhat unique population. For a more complete analysis, it would be necessary to include couples who have chosen not to seek any type of treatment as well as those who are seeking tertiary therapy.

Future research utilizing longitudinal data could examine the predictability of subsequent help seeking from both earlier attitudes toward help seeking as well as previous help seeking behavior in relation to deteriorating marital health. Overall, these findings suggest that the acceptability and success of couples resources’ and interventions may be best informed by future initiatives that seek to address these increased practical and psychological barriers facing couples who need help.

Acknowledgment

Support for this project was provided by a grant (R01HD45281) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the second author.

Contributor Information

C.J. Eubanks Fleming, Psychology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Worcester, MA 01610, (252) 725-5146, cjfleming@clarku.edu.

James V. Córdova, Psychology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Worcester, MA 01610, (508) 793-7274, jcordova@clarku.edu.

REFERENCES

- Amato PR, Booth A. Consequences of Parental Divorce and Marital Unhappiness for Adult Well-Being. Social Forces. 1991;69(3):895–914. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2579480. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bringle RG, Byers D. Intentions to seek marriage counseling. Family Relations. 1997;46(3):299–304. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/585128. [Google Scholar]

- Camerer CF, Hogarth RM. The Effects of Financial Incentives in Experiments: A Review and Capital-Labor-Production Framework. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1999;9(1–3):7–42. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Badger S, Yang C. The ability to negotiate of the ability to love?: Evaluating the developmental domains of marital competence. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1001–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlaine C, Barnes S, Waring EM, Wodd G, Fry R. The role of marital intimacy in psychiatric help-seeking. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;34(1):3–7. doi: 10.1177/070674378903400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(7):741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV. The attitudes toward seeking professional help – Marital therapy questionnaire. Worcester, Massachusetts: Department of Psychology, Clark University; 2007. Unpublished questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Gee CB. The relationship help seeking measure. Department of Psychology, Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts; Worcester, Massachusetts: Department of Psychology, Clark University; 2001. Unpublished questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Jacobson NS, Christensen A. Acceptance vs. change in behavioral couples therapy: Impact on client communication processes in the therapy session. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1998;24:437–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1998.tb01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Scott RL, Dorian M, Mirgain S, Yaeger D, Groot A. The marriage checkup: A motivational interviewing approach to the promotion of marital health with couples at-risk for relationship deterioration. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Warren LZ, Gee CB. Motivational interviewing with couples: An intervention for at-risk couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2001;27:315–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2001.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Marital therapy, retreats, and books: The who, what, when, and why of relationship help-seeking. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2009;35(1):18–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Simpson LE, Christensen A. Why do couples seek marital therapy? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(6):608–614. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SF, Holman TB, Yang C. Factors Associated with Involvement in Marriage Preparation Programs. Family Relations. 2007;56:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner RA, Davey M, Davey A. Gender-related predictrs of change in marital satisfaction and marital conflict. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2005;33:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EH, Turner JL. Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1970;35:79–90. doi: 10.1037/h0029636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good GE, Dell DM, Mintz LB. Male role and gender role conflict: Relations to help seeking in men. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36(3):295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, O’Donnell C, Lizzio A, Wilson KL. Do couple at high risk of relationship problems attend premarriage education? Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(1):160–163. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Sanders MR, Behrens BC. Can skills training prevent relationship problems in at-risk couples? Four-year effects of a behavioral relationship education program. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(4):750–768. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd F, Komiti A, Jackson H. How does being female assist help-seeking for mental health problems? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;42:24–29. doi: 10.1080/00048670701732681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Know VJ. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: The influence of help seeking attitudes. Aging and Mental Health. 2006;10(6):574–582. doi: 10.1080/13607860600641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers LS, Gamst G, Guarino AJ. Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Morrill MI, Fleming CJE, Harp AG, Sollenberger JW, Darling EV, Cordova JV. The Marriage Checkup: Increasing access to marital healthcare. Family Process. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2011.01372.x. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring Marital Quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda VD, Bergstresser SM. Gender, race-ethnicity, and psychosocial barriers to mental health care: An examination of perceptions and attitudes among adults reporting unmet need. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:317–334. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry LAM, Turner LH, Sterk HM. Constructing and reconstructing gender: The links among communication, language, and gender. SUNY series in feminist criticism and theory. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LC, Morris ML. An evaluation of marketing factors in marriage enrichment programs. Family Relations. 1998;47(1):37–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/584849. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Amato PR, Johnson CA, Markman HJ. Premarital education, marital quality, and marital stability: Findings from a large, random household survey. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:117–126. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KT, Bradbury TN. Are premarital prevention programs reaching couples at risk for marital dysfunction? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:24–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrey JL. Self-in-relation: A theory of women's development. Wellesley, Mass: Wellesley College, Stone Center for Developmental Services and Studies; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Wester SR, Wei M, Boysen G. The role of outcome expectations and attitudes on decisions to seek professional help. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(4):459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Uebelacker LA. Distress and impairment associated with relationship discord in a national sample of married or cohabitating adults. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:369–377. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott IH. Seeking help for marital problems before separation. Australian Journal of Sex, Marriage, and Family. 1986;7(3):154–164. [Google Scholar]