Abstract

This study investigates the short-term effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) on programmed death 1 receptor (PD-1) expression and lymphocyte function. We compared lymphocytes from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults prior to the initiation of HAART with lymphocytes from the same subjects following 2 months of treatment. Short-term HAART resulted in a moderate increase in the expression of PD-1 on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; yet, there was still a significant reduction in viral load and recovery of CD4+ T cells. After 2 months of HAART, lymphocytes from the subjects had a reduction in lymphoproliferative responses to phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and an increased response to the Candida recall antigen and the HIV antigen p24 compared to pretreatment lymphocytes. PHA-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from samples obtained 2 months after HAART produced higher levels of Th-1 cytokines (gamma interferon [IFN-γ] and tumor necrosis factor alpha[TNF-α]) than the levels observed for samples taken before treatment was initiated. There were no significant changes in the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-2 (IL-2) or Th-2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10) in the corresponding samples. Ex vivo PD-1 blockade significantly augmented PHA-induced lymphoproliferation as well as the levels of Th-1 cytokines and to a lesser extent the levels of Th-2 cytokines in PBMC cultures. The ability to downregulate PD-1 expression may be important in enhancing immune recovery in HIV infection.

INTRODUCTION

Costimulatory and coinhibitory molecules provide a secondary signal that, in addition to antigen specificity, allows for fine tuning of the intensity of the T-cell response as well as prevents excess immune activation. Programmed death 1 receptor (PD-1) and its ligands, PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and PD-L2, suppress T-cell activation and play a critical role in maintaining tolerance (22). PD-L1 is constitutively expressed by immune cells such as T cells, B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells and is further upregulated after their activation and is also expressed on some nonlymphoid cells (17). PD-1 signaling suppresses the activation of PD-1-expressing cells. In the context of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, PD-1 signaling may contribute to accelerated CD4+ T-cell loss, T-cell exhaustion, poor immune recovery, and disease progression (7, 13, 24, 25). Blockade of PD-1 interactions with antibodies directed against PD-1 or its ligands restores T-cell function and the ability to produce cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) (2, 25). PD-L1 expression is also significantly elevated in monocytes and B cells in the peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals compared with HIV-negative controls (24). HIV and other chronic viruses exploit the PD-1 signaling pathway to ease immune constraints on viral replication (10).

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has markedly improved the quality and duration of life of HIV-infected individuals. Although HAART is associated with the delayed progression of infection to AIDS due to the sustained suppression of viral replication, a significant proportion of patients receiving HAART experience suboptimal CD4 T-cell recovery despite sustained HIV suppression (14, 16). Our studies show that treatment with HAART resulted in an increase in the percentage and absolute number of CD4+ T cells but had only a minimal effect on other lymphocytes assessed. In vitro blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway increases the proliferation of PBMCs after phytohemagglutinin (PHA) stimulation. Of the Th-1/Th-0 cytokines analyzed (IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2), the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α increased after 2 months of HAART, while no Th-2 cytokines analyzed (IL-10, IL-5, and IL-4) were induced. Ex vivo blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway enhanced the expression of both Th-1 and Th-2 cytokines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population.

Fifteen HIV-infected, treatment- naïve adult subjects followed in the MacGregor Clinic at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania were recruited for this study. These patients were also enrolled into the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) protocol A5257, which is a phase III comparative study of three nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-sparing antiretroviral regimens for treatment-naïve HIV-1-infected volunteers. Our protocol was approved by the institutional review board of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Inclusion criteria included plasma HIV-1 RNA level of ≥1,000 copies/ml. The average CD4 T-cell count was 370 ± 68 cells/μl, and the average viral load was 125,300 copies/ml. Subjects were randomized into one of the study's 3 treatment groups. Group 1 received 300 mg of atazanavir (ATV) orally (p.o.) once a day (QD) plus 100 mg ritonavir (RTV) p.o. QD plus 200 mg of emtricitabine and 300 mg of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (200/300 mg FTC/TDF) p.o. QD. Group 2 received 400 mg of Raltegravir (RAL) p.o. twice daily (BID) plus 200/300 mg FTC/TDF p.o. QD. Group 3 received 800 mg Darunavir (DRV) p.o. QD plus 100 mg RTV p.o. QD plus 200/300 mg FTC/TDF p.o. QD. The exact treatment regimen for individuals enrolled in the study was not disclosed to us, and all samples regardless of the regimen received are pooled in the analyses completed for this article. The study population consisted of 2 females and 13 males, 5 Caucasians and 10 African-Americans, 25 to 55 years old. Consenting subjects were enrolled with 25 ml of blood obtained prior to the initiation of HAART and at 2 months after treatment. CD4 counts were monitored as part of the ACTG-A5257 protocol for a period of more than 1 year. The viral loads were measured at Johns Hopkins University HIV Specialty Laboratories using Abbott Realtime HIV-1.

Flow cytometry immunophenotyping.

Four-color flow cytometry was used to evaluate PD-1 expression on CD3+ CD8+ and CD3+ CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD14+ monocytes (3). The directly conjugated murine monoclonal antibodies included allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD14, tandem conjugate peridinin chlorophyll protein complex with cyano dye (PerCP-Cy5.5) anti-CD3, tandem conjugate allophycocyanin with cyano dye 7 (APC-Cy7) anti-CD8, and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated murine isotype control antibody (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). PE-conjugated anti-PD-1 antibodies were obtained from BioLegend, San Diego, CA.

Lymphoproliferative assay (LPA) in the presence and absence of coinhibitory antibodies.

Lymphoproliferative responses to phytohemagglutinin (PHA), Candida and HIV p24 were evaluated using freshly isolated whole-blood-derived PBMCs. PHA (Sigma), the HIV-specific antigen p24 (ABI), and Candida antigen (Greer Laboratories) were added to cells in the following final concentrations: 20 μg/ml for PHA, 1 μg/ml for the HIV-specific antigen p24, and 50 μg/ml for Candida antigen. Cells (1 × 105 cells for PHA and Candida and 2 × 105 cells for p24) in 0.2 ml of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% pooled normal human AB sera were cultured in triplicate at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 6 days in the presence and absence of a combination of monoclonal antibodies directed against PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), and CD28/CD49d costimulatory reagent (BD, San Jose, CA) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Each well was pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine ([3H]TdR) during the last 6 h of culture. The cells were harvested onto a 96-well LumaPlate and dried overnight. Radiolabeling was measured with a TopCount scintillation counter (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA). Mean counts per minute (cpm) were recorded for resting, PHA-, Candida-, and p24-stimulated cultures with data expressed as net cpm (mean stimulated cpm − mean resting cpm) or as stimulation index (SI) (mean stimulated cpm/mean resting cpm).

PHA-induced PBMC Th-1/Th-2 cytokine production as assessed by cytometric bead array assay.

A flow cytometry-based cytometric bead array (CBA; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) assay was used to measure Th-1/Th-2 cytokines in culture supernatants of PBMCs stimulated with PHA for 24 h. Cells were cultured in the presence and absence of a combination of monoclonal antibodies directed against the coinhibitory receptor (PD-1) and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2), as well as costimulatory receptors (CD28/CD49d) as described above at a cell density of 1 × 106/ml in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% pooled normal human AB sera at 37°C under 5% CO2. Aliquots (70 μl) of culture supernatants were removed from 1-ml cultures at 24 h and frozen at −70°C until evaluated for Th-1/Th-2 cytokines by cytometric bead array assay according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses of cell markers, LPA response, and cytokine production were performed using the Student two-tailed t test for paired observations and correlation coefficient calculations using Prism software (GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

HAART is associated with decreased viral load and increased PD-1 expression on CD4+ T cells.

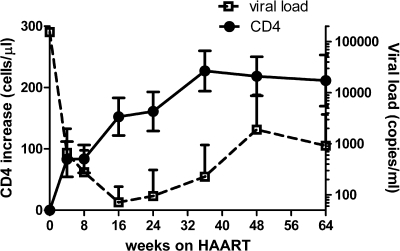

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from 15 antiretroviral-naïve HIV-positive patients treated with one of the HAART drug regimens described above. The viral load in all patients dramatically decreased in the first 2 months after initiation of HAART (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Eight weeks following HAART, average viral loads decreased by approximately 3 log units. At this time point, 7 subjects still had detectable virus, while 8 had viral loads below the detection level of 40 copies per ml. After 24 weeks of treatment, viral loads fell below detectable level in all but one subject. This subject never achieved complete viral suppression and had viral loads increasing above the enrollment level by week 48 (reflected in Fig. 1). In another subject, viral loads were undetectable from week 24 to 48 but rebounded at week 64 to 631 copies per ml. In the remaining 13 subjects, viral loads remained below the detection level from week 24 to 64. CD4 T-cell counts begin to recover as early as 4 weeks after start of HAART and continued to show sustained improvement over baseline for the duration of the observation period (Table 1 and Fig. 1). After 2 months, the percentage of CD4+ T cells was significantly increased (P = 0.02) and the percentage of CD8+ T cells was significantly diminished (P = 0.04). The percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing PD-1 was also significantly increased (P = 0.02) as was PD-1 expression on CD8+ T cells; however, this increase was not significant (P = 0.3) (Table 1). The percentage of CD14-positive cells decreased following 2 months of HAART. The changes in PD-1 did not correlate with either decrease in viral load (VL) or increase in CD4 T-cell counts.

Table 1.

Viral loads and cell phenotype markers

| Parameter | Value at the following timea: |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before HAART | After HAART | ||

| Viral load (log10 copies/ml) | 5.10 ± 4.61 | 2.45 ± 2.14 | <0.0001 |

| % CD4 cells | 34.1 ± 3 | 37.8 ± 3 | 0.02 |

| Absolute no. of CD4 cells (no. of cells/μl) | 370 ± 68 | 455 ± 126 | 0.01 |

| % CD4+ PD1+ | 19.1 ± 4 | 34.6 ± 5 | 0.02 |

| Absolute no. of CD4+ PD-1+ (no. of cells/μl) | 89.8 ± 22 | 136.5 ± 30 | 0.17 |

| % CD8 | 64.5 ± 3 | 61.1 ± 3 | 0.04 |

| Absolute no. of CD8 (no. of cells/μl) | 1187 ± 193 | 1213 ± 170 | 0.8 |

| % CD8+ PD-1+ | 31.0 ± 7 | 37.7 ± 6 | 0.3 |

| Absolute no. of CD8+ PD-1+ (no. of cells/μl) | 295 ± 99 | 427 ± 98 | 0.2 |

| % CD14 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.04 |

| % CD14+ PD-1+ | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.5 |

Values are shown before HAART and after 2 months of HAART. Values are averages ± standard errors.

The P values show the statistical comparison of the values before and after HAART. Statistically significant (P < 0.05) values are shown in boldface type.

Fig 1.

Viral load decreased and CD4 T-cell count increased in 15 patients during 64 weeks of HAART. Data are presented as increase in the absolute number of CD4 T cells over the baseline number and as the number of copies of viral RNA per ml of blood (values are means ± standard deviations [error bars]).

PD-1 blockade increases proliferative responses to mitogen.

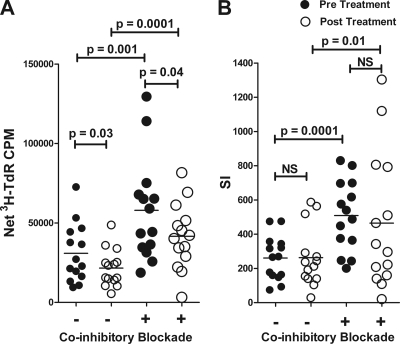

We tested the ability of T cells to respond to mitogenic stimuli before or after the initiation of HAART. Response to stimuli was measured by determining the proliferation rate as either cpm or stimulation index (SI). Comparison of antigen- and PHA-induced proliferation evaluated before and after HAART revealed an increase in antigen-specific proliferation as a result of HAART for both recall Candida antigen and HIV-specific p24 antigen, but only the Candida-specific increase was significant (not shown). Four out of 15 subjects had a reduced response against Candida antigen (SI < 10) before HAART. Candida response recovered after 2 months of therapy (SI > 10 in all subjects). The average Candida SI increased from 94 to 219 (P = 0.03). Only one subject had a p24 SI above 10 before HAART, while three had a p24 SI above 10 after HAART. The average increase in p24-specific SI was from 4.5 to 7.7 (P > 0.05). Blockade of PD-1 did not change either the Candida- or p24-specific proliferative response (not shown).

HAART treatment alone reduces the proliferative response to PHA compared to pretreatment levels but only when expressed as cpm and not as SI (Fig. 2). Increased expression of PD-1 as a result of HAART (shown in Table 1) would be predicted to suppress proliferation. Blockade of coinhibitory interactions augmented proliferative responses to PHA in both pre- and posttreatment samples with average SI increase from 261 to 487 (P = 0.01) (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Freshly isolated PBMCs were cultured for 6 days in the presence of PHA with (+) or without (−) anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Lymphoproliferation is expressed as cpm (A) or stimulation index (SI) (B). Each symbol represents the value for an individual sample, and the short black line represents the mean for a group of samples. NS, not significant.

Effects of HAART and coinhibitory blockade on PHA- and antigen-specific Th-1/Th-2 cytokine production.

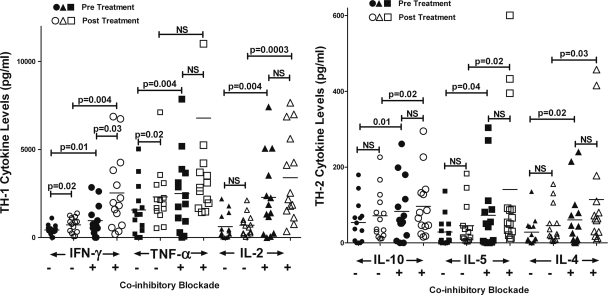

Two months of HAART resulted in a significant increase in the production of Th-1 cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α) by PHA-stimulated human PBMCs; however, there was no significant change in production of the Th-1/Th-0 cytokine IL-2 (Fig. 3). In contrast, HAART did not change the production levels of Th-2 cytokines (IL-10, IL-5, and IL-4). In vitro blockade of PD-1 resulted in significant upregulation of both Th-1 and Th-2 cytokines (Fig. 3), indicating that blockade of the PD-1/PD-L pathway appears to relieve T-cell exhaustion.

Fig 3.

PBMCs were collected before and after 2 months of HAART treatment. Cytokine (CK) production was measured 24 h after stimulation with PHA and with or without PD-1 blockade as indicated. Each symbol represents the value for an individual sample, and the short black line represents the mean for a group of samples. There were 14 samples in each group. The PBMC sample from one subject had insufficient number of cells for analysis.

DISCUSSION

Fifteen treatment-naïve, HIV-infected patients were administered HAART for 2 months resulting in a significant decrease in plasma viral loads in all subjects. We also observed a rapid recovery of CD4 T cells consistent with previous HAART studies (1, 4, 15, 19). The early increase in CD4 T-cell count was attributed to recirculation of memory T cells from lymphoid tissues seen during the first 2 to 3 months of HAART, which is followed by a sustained but slow T-cell recovery persisting over the years (1). In our study, we also observed rapid recovery of CD4 T cells reaching a maximum at week 36 followed by some decrease at weeks 48 and 64 (Fig. 1). The decrease was associated with a reduction in CD4 counts in 2 subjects, one with incomplete virus suppression and another with virus rebound. In addition, CD4 T-cell recovery reached a plateau in 7 out of 13 subjects with complete viral suppression from week 24 to 64 of HAART.

CD4+ T-cell counts often correlate poorly with plasma HIV RNA levels, an indicator of active viral replication (13). PD-1 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells has a strong inverse correlation with the absolute number of CD4+ T cells in HIV-positive individuals, and there are a number of reports linking incomplete CD4 T-cell recovery in patients undergoing HAART to cell damage inflicted by the PD-1/PD-L system (7, 11, 24). Grabmeier-Pfistershammer et al. reported that PD-1 expression is reduced in individuals who control viremia but not in those that fail to control viremia (11). We observed a moderate increase in expression of PD-1 receptor on CD4 and CD8 T cells during the first 2 months of therapy irrespective of viral loads. Increased PD-1 expression does not appear to be correlated with the inability to control virus, as PD-1 expression also increased in the majority of patients with undetectable virus during weeks 24 to 64. In 7 subjects with detectable viral loads at week 8, four had increased percentages of PD-1-positive CD4 T cells compared to baseline, two had decreased percentages, and in one subject, the percentage did not change. By comparison, among 8 subjects with undetectable virus at week 8, six had increased percentages of PD-1-positive T cells, one had a decreased percentage, and in two subjects, the percentage did not change. Increased PD-1 expression may delay CD4 T-cell recovery. Of 15 patients studied, 14 had virologic and CD4 responses to HAART. PD-1 upregulation was linked to prolonged antigen exposure of the immune system with sustained viremia in HIV-infected individuals. Although we observed significant inhibition of viral replication after 2 months of HAART, low levels of viral RNA were still detectable in blood from several patients. As a result we cannot rule out a continuous exposure of the immune system to low doses of viral antigens. A longer observation period is required in order to determine whether the increased PD-1 expression during the first 2 months of HAART is a transient or persistent phenomenon. Additionally, we cannot conclude whether our observation is a general phenomenon or is related to a specific HAART regimen, since this laboratory study is blinded to the medication used by the subjects.

Two months of HAART was also associated with a decrease in the percentage of circulating CD14+ monocytes. An increase in some subpopulations of CD14 cells (such as CD14hi CD16+) occurs in association with HIV progression and was recovered as a result of HAART (12). An increase in the expression of CD14 in HIV-infected individuals may be related to persistent macrophage activation due to the damage of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and increased microbial/lipopolysaccharide (LPS) infusion (27). The observed decrease in the percentage of CD14+ cells is likely a reflection of overall immune restoration resulting from HAART.

We observed moderate improvement in antigen-specific proliferation to recall antigen following 2 months of HAART. This is consistent with previous reports (20, 21) and may serve as evidence of early signs of immune recovery. We also observed a decrease in PHA-induced proliferation when expressed as net cpm; however, when expressed as SI, PHA induced proliferation was unchanged by HAART. This discrepancy is a result of the manner in which the data were analyzed. The background cpm in the control nonstimulated cultures were significantly reduced in samples from post-HAART patients, yet this reduction did not correlate with the absolute T-cell count. It is likely a reflection of a general reduction of immune activation as a result of HIV suppression by HAART. Antibody blockade of coinhibitory signaling led to enhanced mitogen- but not antigen-induced lymphoproliferation, consistent with our previous report (3). HAART did not change the proliferation response of PBMCs to PD-1 blockade.

PBMC cultures from post-HAART samples produced significantly higher quantities of two Th-1 cytokines, IFN-γ and TNF-α, compared to samples collected before treatment. No such increase was detected for Th-2 (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10) or the Th-0 proinflammatory cytokine IL-2. A highly functional T-cell population (e.g., during immune response) is associated with high levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 production, while T-cell exhaustion is associated with a loss of their production (10). The T-cell response usually shifts from Th-1 to Th-2 during HIV progression, although this remains controversial. There are data that the restoration of Th-1 cytokine production is associated with successful therapy (9, 23). No detectable shift in Th-1 to Th-2 production was reported in adolescents at an early stage of HIV (8), while a shift in Th-1/Th-2 immune response occurred as HIV infection progresses to AIDS (18).

PD-1 blockade increased production of both Th-1 and Th-2 cytokines by PBMCs with a more profound effect seen for Th-1 cytokines. These findings are generally consistent with our earlier observations (3). In an earlier study, we did not see an increase in IL-10 production in cultures treated with anti-PD-1 antibodies. The fact that PD-1 blockade stimulates Th-1 is not surprising, since upon interaction with its natural ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2), PD-1 abrogates the effector function of both immunoregulatory CD4 and cytolytic CD8 T cells while promoting the induction of IL-10 in HIV-infected individuals (22). PD-1/PD-L1 blockade downregulates IL-10 but upregulates IL-2 and IFN-γ during in vitro stimulation under conditions other than HIV infection (5, 6). Some differences between our current study and early publications regarding the influence of PD-1 blockade on IL-10 expression may be explained by the fact that previous studies were conducted in HIV-positive subjects on maintenance antiretroviral therapy, while current samples were obtained either from HAART-naïve individuals or after relatively brief HAART.

Increased PD-1 expression in vivo early in immune reconstitution deserves further attention in an expanded longitudinal study. Analysis of the effects of PD-1 blockade in vitro may lead to development of new assays for monitoring HIV progression and the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy in immunological recovery. PD-1 blockade administered along with antiretroviral therapy may help to improve immune restoration in vivo, as it has yielded promising results in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques (26).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) Group was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (U01 AI068632), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (AI068632). This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at the Harvard School of Public Health under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement 5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and 1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C).

We thank Carol Vincent, the Philadelphia Clinical Trials Unit Coordinator, and Pablo Tebas, the University of Pennsylvania Clinical Research Site Leader, site 6201. We also thank Wayne Wagner, Aleshia Thomas, Kathryn Maffei, and Carol DiGiorgio from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania who graciously recruited and obtained consent from the subjects for this study. We thank Christa Heyward for editorial assistance.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 March 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Autran B, et al. 1997. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science 277:112–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barber DL, et al. 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439:682–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell DE, et al. 2009. Cryopreservation decreases receptor PD-1 and ligand PD-L1 coinhibitory expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived T cells and monocytes. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1648–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carcelain G, Debre P, Autran B. 2001. Reconstitution of CD4+ T lymphocytes in HIV-infected individuals following antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13:483–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen L, et al. 2007. B7-H1 up-regulation on myeloid dendritic cells significantly suppresses T cell immune function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J. Immunol. 178:6634–6641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Curiel TJ, et al. 2003. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nat. Med. 9:562–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Day CL, et al. 2006. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 443:350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Douglas SD, et al. 2003. TH1 and TH2 cytokine mRNA and protein levels in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive and HIV-seronegative youths. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:399–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fournier S, et al. 2001. Immune recovery under highly active antiretroviral therapy is associated with restoration of lymphocyte proliferation and interferon-gamma production in the presence of Toxoplasma gondii antigens. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1586–1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, Sharpe AH. 2006. Reinvigorating exhausted HIV-specific T cells via PD-1-PD-1 ligand blockade. J. Exp. Med. 203:2223–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Steinberger P, Rieger A, Leitner J, Kohrgruber N. 2011. Identification of PD-1 as a unique marker for failing immune reconstitution in HIV-1-infected patients on treatment. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 56:118–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han J, et al. 2009. CD14(high)CD16(+) rather than CD14(low)CD16(+) monocytes correlate with disease progression in chronic HIV-infected patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 52:553–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holm M, Pettersen FO, Kvale D. 2008. PD-1 predicts CD4 loss rate in chronic HIV-1 infection better than HIV RNA and CD38 but not in cryopreserved samples. Curr. HIV Res. 6:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelley CF, et al. 2009. Incomplete peripheral CD4+ cell count restoration in HIV-infected patients receiving long-term antiretroviral treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:787–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lederman MM, et al. 1998. Immunologic responses associated with 12 weeks of combination antiretroviral therapy consisting of zidovudine, lamivudine, and ritonavir: results of AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 315. J. Infect. Dis. 178:70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakanjako D, et al. 2008. Sub-optimal CD4 reconstitution despite viral suppression in an urban cohort on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in sub-Saharan Africa: frequency and clinical significance. AIDS Res. Ther. 5:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okazaki T, Honjo T. 2006. The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 27:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Osakwe CE. 2010. TH1/TH2 cytokine levels as an indicator for disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and response to antiretroviral therapy. Roum. Arch. Microbiol. Immunol. 69:24–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pakker NG, et al. 1998. Biphasic kinetics of peripheral blood T cells after triple combination therapy in HIV-1 infection: a composite of redistribution and proliferation. Nat. Med. 4:208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peruzzi M, Azzari C, Galli L, Vierucci A, De Martino M. 2002. Highly active antiretroviral therapy restores in vitro mitogen and antigen-specific T-lymphocyte responses in HIV-1 perinatally infected children despite virological failure. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 128:365–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pontesilli O, et al. 1999. Antigen-specific T-lymphocyte proliferative responses during highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) of HIV-1 infection. Immunol. Lett. 66:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Said EA, et al. 2010. Programmed death-1-induced interleukin-10 production by monocytes impairs CD4+ T cell activation during HIV infection. Nat. Med. 16:452–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sondergaard SR, et al. 1999. Immune function and phenotype before and after highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 21:376–383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trabattoni D, et al. 2003. B7-H1 is up-regulated in HIV infection and is a novel surrogate marker of disease progression. Blood 101:2514–2520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Trautmann L, et al. 2006. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nat. Med. 12:1198–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Velu V, et al. 2009. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature 458:206–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wallet MA, et al. 2010. Microbial translocation induces persistent macrophage activation unrelated to HIV-1 levels or T-cell activation following therapy. AIDS 24:1281–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]