Abstract

The individual role of the outer dynein arm light chains in the molecular mechanisms of ciliary movements in response to second messengers, such as Ca2+ and cyclic nucleotides, is unclear. We examined the role of the gene termed the outer dynein arm light chain 1 (LC1) gene of Paramecium tetraurelia (ODAL1), a homologue of the outer dynein arm LC1 gene of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, in ciliary movements by RNA interference (RNAi) using a feeding method. The ODAL1-silenced (ODAL1-RNAi) cells swam slowly, and their swimming velocity did not increase in response to membrane-hyperpolarizing stimuli. Ciliary movements on the cortical sheets of ODAL1-RNAi cells revealed that the ciliary beat frequency was significantly lower than that of control cells in the presence of ≥1 mM Mg2+-ATP. In addition, the ciliary orientation of ODAL1-RNAi cells did not change in response to cyclic AMP (cAMP). A 29-kDa protein phosphorylated in a cAMP-dependent manner in the control cells disappeared in the axoneme of ODAL1-RNAi cells. These results indicate that ODAL1 is essential for controlling the ciliary response by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic cilia and flagella are cell organelles for motility and sensing and have various important roles in biological processes. The locomotor behavior of Paramecium depends on ciliary movements. The ciliary movements are controlled by changes in the membrane potential that regulate the intraciliary concentrations of Ca2+ and cyclic nucleotides. For example, membrane depolarization in response to a mechanical or chemical stimulus applied to the anterior membrane causes an increase in the intraciliary Ca2+ concentration (13), which results in a change in the ciliary orientation toward the anterior direction of the cell (ciliary reversal) and a change in the swimming direction (24). Membrane hyperpolarization in response to a mechanical or chemical stimulus applied to the posterior membrane causes an increase in the intraciliary cyclic AMP (cAMP) concentration (38). This induces an increase in the ciliary beat frequency and changes the ciliary orientation to a more posterior orientation, which causes faster forward swimming (11, 25–30). In addition, cAMP suppresses Ca2+-induced ciliary reversal (11, 25–30). However, the molecular bases of the control mechanism of ciliary movements are unclear.

The outer and inner dynein arms, which are multisubunit complexes attached to the outer surface of the peripheral microtubule doublets, generate forces that cause ciliary and flagellar movements. These multisubunit complexes are composed of one or more catalytic heavy chains (HCs) associated with several intermediate chains (ICs) and light chains (LCs). It has been postulated that certain outer dynein arm LCs are responsible for the regulation of ciliary and flagellar movements. For example, the outer dynein arm of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii comprises 3 HCs, 2 ICs, and 11 LCs (19). Among the LCs, LC1 associates directly with the catalytic motor domain of γHC (8, 33, 45). The expression of dominant negative LC1 mutant proteins in wild-type C. reinhardtii cells showed significant alterations in the flagellar waveform (33). A Trypanosoma brucei outer dynein arm LC1 knockdown mutant created by RNA interference (RNAi) exhibited slow backward propulsion and a reversed flagellar beat (6). In addition, the loss of LC1 induced the destabilization of the outer dynein arms. In the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea, a reduction in levels of LC1 by RNAi caused a significant drop in the ciliary beat frequency and abolished the ability of beating cilia to form metachronal waves (36). However, the precise role of LC1 of dynein complexes in the molecular mechanisms of ciliary and flagellar movements is unclear. The control of ciliary and flagellar movements depends on second messengers, such as Ca2+ and cyclic nucleotides. Therefore, determining how defects of LC1 affect the regulation of the ciliary and flagellar responses to second messengers is essential to an understanding of the role of the dynein subunits in the molecular mechanisms.

We have shown previously that a cortical sheet, an experimental system that we developed, is a useful tool to analyze the ciliary movements of Paramecium (26–29, 31). In addition, the Paramecium tetraurelia genome database, a ciliary proteome database, and protocols for genetic engineering by RNAi are available (1–4, 14). Therefore, ciliated Paramecium could be a useful model organism to study the role of axonemal proteins in the molecular mechanisms of ciliary movements.

In this study, we focused on a gene termed the outer dynein arm light chain 1 gene of P. tetraurelia (ODAL1), a homologue of the LC1 gene of C. reinhardtii. We analyzed the role of ODAL1 in ciliary movements by RNAi using a feeding method (14). Our results indicate that the ODAL1 gene is essential for controlling cAMP-dependent ciliary movement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

P. tetraurelia (stock 7.2B) cells were cultured in a hay infusion bacterized with Enterobacter aerogenes and supplemented with 0.8 μg/ml β-sitosterol according to standard procedures (40). The cells were grown to the late logarithmic phase at 25°C.

Gene silencing by RNAi using the feeding method.

The open reading frame region of ODAL1 (GenBank accession no. XM_001446309) was amplified by PCR and cloned into the Litmus28i vector (New England BioLabs) between two T7 promoters. The amplification primers used were f1 (ATGGCAAAGACAACTTGTG) and r1 (TCATTTGACAGTGGTTGTAG). The resulting constructs were used for the transformation of HT115, an RNase III-deficient strain of Escherichia coli with an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible T7 polymerase (42). RNAi gene silencing was performed according to a feeding method described previously by Galvani and Sperling (14), with modifications. Wild-type paramecia were incubated in a culture medium containing 0.8 μg/ml β-sitosterol, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 0.4 mM IPTG. Gene silencing was initiated by the addition of double-stranded RNA-expressing bacteria to the culture medium (14). One day or two days after the induction of gene silencing, the cells were used for the experiments in this study. The phenotypes of ODAL1-silenced (ODAL1-RNAi) cells were the same after 1 day and 2 days of gene silencing. Nonsilenced P. tetraurelia cells were used as the control cells. As a negative control, we used ND7 silencing, which affects trichocyst exocytosis without altering the ODAL1 gene or any other cellular function (16, 37). Furthermore, we analyzed the off-target effect of ODAL1 silencing using the ParameciumDB P. tetraurelia genome database (http://paramecium.cgm.cnrs-gif.fr/) (1).

Competitive PCR.

One microgram of each poly(A)+ RNA was reverse transcribed by using PrimeScript reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Japan). A 2-μl aliquot of cDNA was added to each PCR mixture, which also contained 1.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0 at room temperature), 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 0.4 μM each primer described above. The amplification protocol consisted of one cycle at 94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s; 24 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 55°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. To quantitatively compare the PCR products, we determined the exponential phase of amplification by performing amplification for 15, 20, 25, and 30 cycles, using the ODAL1 primers 5′-CTTTCTTCAAATGCAATAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CATTTAGGGTCATCTTTC-3′ (antisense). In addition, as an internal control for cDNA quantity and quality, we amplified the gene for beta-actin by using the primers 5′-TTGATTATGAAGAGGAAATG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCTGTGGACAATGGTTGG-3′ (antisense). Amplified PCR products were electrophoresed in 2.0% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. To quantify the relative amounts of each PCR product, the ethidium-stained gels were reversed and analyzed by using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). The ratios of ODAL1 mRNA to beta-actin mRNA were calculated based on the densities of the PCR products (7, 15, 32, 39).

Assays of swimming behavior.

Approximately 50 μl of a cell culture containing 40 to 50 live cells was placed by a micropipette onto a depression slide. Membrane-hyperpolarizing stimulation was performed by the addition of CaCl2 to attain a Ca2+ concentration of 2 mM in the cell culture (22). After the addition of CaCl2, the behaviors of individual cells were observed under a VCT-VBITVb digital microscope (Shimadzu, Japan) and recorded for 1 s. A sequential image of the swimming path was prepared from the recorded frames by using Motic Images Plus 2.1S (Shimadzu, Japan). The forward swimming velocity was determined by measuring the length of the swimming path by using ImageJ. Membrane-depolarizing stimulation was performed by the addition of KCl to attain a K+ concentration of 50 mM in the cell culture. After the addition of KCl, backward swimming was observed by using a VCT-VBITVb digital microscope, and the duration of the backward swimming was determined.

Preparation and reactivation of cortical sheets from live cells.

The preparation of cortical sheets from live cells (intact cortical sheets) was performed according to methods described in our previous paper (31), with slight modifications. Concentrated cells were washed by centrifugation with an ice-cold washing medium containing 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM potassium acetate, and 10 mM Tris-maleate buffer (pH 7.0). The loose pellet of cells was resuspended in 1 ml of an ice-cold potassium acetate solution containing 50 mM potassium acetate and 10 mM Tris-maleate buffer (pH 7.0). The cells were pipetted once or twice through a glass pipette with a small inside diameter (approximately 0.15 mm) to tear or nick the cell cortex. This cell suspension was used for the reactivation experiments. A simple perfusion chamber was prepared by placing the sample between a slide and a coverslip. The slide and coverslip were separated by a thin layer of Vaseline applied to two opposite edges of the coverslip. To observe the reactivation of cilia on the sheet of cell cortex, 50 μl of the sample was gently placed onto a glass slide, and a coverslip with Vaseline was placed over the sample. Solutions were then perfused through the narrow opening at one of the edges of the coverslip, while the excess fluid was drained from the opposite end with the aid of small pieces of filter paper. During the first perfusion using a reference potassium acetate solution, some torn cell cortex adhered flat to the glass surface.

Cortical sheets were perfused successively with reactivation solutions. All reactivation solutions contained 50 mM potassium acetate and 10 mM Tris-maleate buffer (pH 7.0) as well as a component(s), such as MgCl2, ATP, and cyclic nucleotide, as noted in Results and the figure legends. The free Ca2+ concentration of 2 × 10−6 M and lower in the reactivation solutions was controlled by using Ca-EGTA buffer (34), using 1 mM EGTA; a concentration of >2 × 10−6 M was obtained by the addition of an adequate amount of CaCl2 to a reactivation solution without EGTA. The reactivation of cilia was carried out at 22°C to 25°C. To determine the ciliary beat frequency, the reactivation of cilia on intact cortical sheets was performed in the presence of 5 μM cyclic GMP (cGMP) throughout, because reactivated cilia without cGMP beat in an abnormal manner to some extent (27).

The ciliary orientation was observed in the presence of 30% glycerol to clearly determine the ciliary orientation (26, 28, 29). Intact cortical sheets were demembranated by perfusion with a Triton solution containing 0.05% Triton X-100, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM potassium acetate, and 10 mM Tris-maleate (pH 7.0) for 1 min and then washed by perfusion with the same solution without Triton X-100 to remove Triton X-100. The demembranated cortical sheets were incubated in a glycerol solution containing 30% glycerol, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM potassium acetate, and 10 mM Tris-maleate (pH 7.0) for 5 min. The cilia were reactivated by perfusion with reactivation solutions containing 30% glycerol, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM potassium acetate, and 10 mM Tris-maleate (pH 7.0) as well as Ca2+ and cAMP, as noted in Results and the figure legends. In the presence of 30% glycerol, the reactivated cilia on the cortical sheets exhibited only a restricted beat with a small amplitude. However, the pointing directions of the cilia changed in response to Ca2+ and cAMP reversibly (26, 28, 29).

Observation and recording of reactivated cilia.

The reactivated cilia on cortical sheets were observed under a dark-field microscope equipped with a 100-W mercury light source, a heat filter, and a green filter. The ciliary movements were recorded by using an HAS-220 high-speed camera (Ditect, Japan). To determine the ciliary beat frequency, recording was performed at 600 frames per s, and to determine the ciliary direction, recording was performed at 100 frames per s.

Analysis of ciliary movements on cortical sheets.

The movements of the reactivated cilia on intact cortical sheets were analyzed by using ImageJ. We analyzed cilia on the left-hand field of the sheet, defining the surface area of the anatomical left-hand side as the left-hand field of the cortical sheets (28). The beat frequency of the reactivated cilia was determined by the direct measurement of the ciliary beat cycle by monitoring the recorded video images frame by frame (31). The method for determining the ciliary orientation was essentially the same as that described in our previous papers (26, 28, 29). Three cilia on several independent cortical sheets from at least two independent RNAi preparations were measured for ciliary beat frequency and ciliary orientation.

Isolation of cilia.

Collected cells were washed twice with a washing solution containing 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Tris-maleate (pH 7.0). Cells were deciliated by dibucaine treatment according to methods described previously by Mogami and Takahashi (23), with slight modifications (29). Cilia were isolated from cell bodies by centrifugation twice at 600 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 7,700 × g for 10 min to pellet the cilia. The pellet was resuspended in TMKE solution (10 mM Tris-maleate [pH 7.0], 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM potassium acetate, and 1 mM EGTA) containing 0.3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and centrifuged. The pellet was rewashed with TMKE solution. Each step of the cilium isolation was monitored by dark-field microscopy. Isolated cilia were then treated with a demembranation solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100 in TMKE solution for 10 min at 0°C. The suspension was centrifuged to pellet the axonemes. Triton X-100 was removed from the axonemes by washing twice with TMKE solution. The pellet of the axonemes was suspended in a small amount of TMKE solution.

Phosphorylation of axonemal proteins.

The in vitro phosphorylation of the axonemes was performed according to methods described previously by Hamasaki et al. (18), with slight modifications. The reaction mixture contained 75 μg axonemes and 30% glycerol in 80 μl TMKE solution as well as test substances. Phosphorylation by endogenous protein kinases was started by the addition of 20 μl of [γ-32P]ATP to attain a final concentration of 2 μM ATP. The ATP concentration of [γ-32P]ATP was 10 μM, and the radioactivity was adjusted to 10 μCi with adenosine 5′-[γ-32P]triphosphate (specific activity, 6,000 Ci/mmol; MP Biomedicals Inc., Solon, OH). Immediately after 10 min of incubation at 0°C, the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was directly suspended in SDS sample buffer (2% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.5% bromophenol blue, and 62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8]) and incubated at 100°C for 2 min. These SDS-treated samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE or stored at −20°C for further use. The protein concentration was determined according to methods described previously by Lowry et al. (21), using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

SDS-PAGE was performed by a modification of a procedure described previously by Laemmli (20), using 3-to-15% linear gradient acrylamide gels containing a 0 to 19% glycerol gradient run on a 20- by 16- by 0.1-cm slab gel. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue R-250 for 15 min or with silver (10) and dried on filter paper. Molecular weight standards were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). To produce the autoradiograms, an imaging plate (IP; Fujifilm Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was placed over the dried gels for 2 days. After exposure, the IP was scanned by using a bioimaging analyzer system (BAS-1800; Fujifilm Corp.).

Electron microscopy.

For electron microscopy, cells were fixed in 1% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were washed and postfixed in 1% (wt/vol) OsO4 for 1 h at room temperature. Postfixation was followed by washing in distilled water and then dehydration in a series of increasing concentrations of ethanol and, finally, 100% propylene oxide. The cells were flat embedded in Quetol 812 (Nisshin EM Co., Ltd., Japan). Following evacuation and hardening, the cells were cut out of the block and glued onto another polymerized preshaped block. These cells were serially sectioned in a longitudinal orientation, and all of the sections were picked up on Formvar-supported grids having one large opening. The grids were placed in chronological order so that the exact position of each section within the entire series could be determined. A diamond knife (Nisshin EM Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and Ultracut E (Reichert, Buffalo, NY) were used for sectioning. Sections were then stained at room temperature with uranyl acetate (43) and lead citrate (35) for 7 min and 3 min, respectively. A transmission electron microscope (H-7000; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 75 kV was used throughout the study.

RESULTS

Characteristics of ODAL1.

The ODAL1 gene of P. tetraurelia (GenBank accession no. XM_001446309) encodes a protein whose predicted sequence is 38% identical to outer dynein arm LC1 of C. reinhardtii (accession no. AF112476), and such a protein was detected in the P. tetraurelia genome database and the ciliary proteome database (1–4). The ODAL1 gene includes the conservation of most residues that directly bind the outer dynein arm γHC catalytic motor domain and tubulin (8, 33, 45) (Fig. 1). It is presumed that the ODAL1 product has a molecular mass of 22 kDa. The cAMP-dependent phosphorylation site was predicted by using NetPhosK 2.0 (9) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Sequence comparison between P. tetraurelia and C. reinhardtii. The deduced amino acid sequence alignment between ODAL1 of P. tetraurelia (GenBank accession no. XM_001446309) and the C. reinhardtii LC1 gene (accession no. AF112476) was generated with Clustal W (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw/) and was displayed by using Boxshade (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html). Black boxes indicate identical residues. Gray boxes indicate conservative substitutions. Most of the key residues were conserved, including the γHC catalytic domain binding sites (+) and the tubulin binding sites (#). The arrowhead indicates the putative amino acid (S55), which is strongly predicted to become phosphorylated in a cAMP-dependent manner by the NetPhos 2.0 program (9).

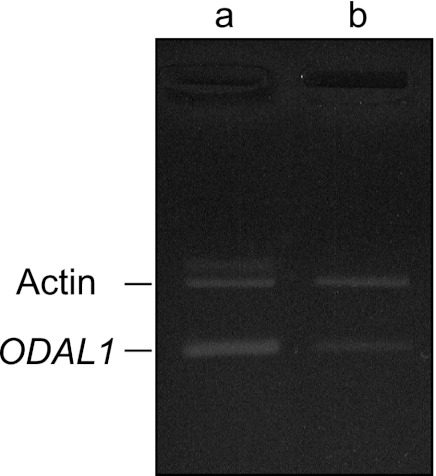

Confirmation of ODAL1 silencing by RNAi.

We confirmed the effect of ODAL1 silencing by RNAi using competitive PCR. ODAL1 mRNA was expressed over 2-fold compared with beta-actin mRNA in nonsilenced cells (control) (Fig. 2). When the paramecia were fed E. coli including a knockdown plasmid, however, the amount of ODAL1 mRNA was strikingly decreased, even within 1 day after feeding (Fig. 2). Compared to control cells, the level of ODAL1 mRNA was 6-fold lower in ODAL1-silenced paramecia.

Fig 2.

Competitive PCR of ODAL1. Shown are electrophoresis images of ethidium bromide-stained gels of ODAL1 and beta-actin expression in control cells (lane a) and ODAL1-RNAi cells (1 day after the induction of gene silencing) (lane b). Each silencing paramecium was grown at 28°C and harvested at 1 day after feeding. One microgram of poly(A)+ RNA of each culture was PCR amplified by using primers specific for the ODAL1 and beta-actin genes for 25 cycles. Actin and ODAL1 indicate the PCR products of the beta-actin (loading control) and the ODAL1 genes, respectively.

Furthermore, the off-target effect of ODAL1 silencing was analyzed. For ODAL1 silencing, the RNAi off-target has four genes: 3 genes are itself and its ohnologues, and the other has a completely different function, but its inactivation by this RNAi is very unlikely, since only a single 23-nucleotide (nt) siRNA can target it (data not shown). Therefore, it seems that there are no off-targets and that the RNAi insert is specific.

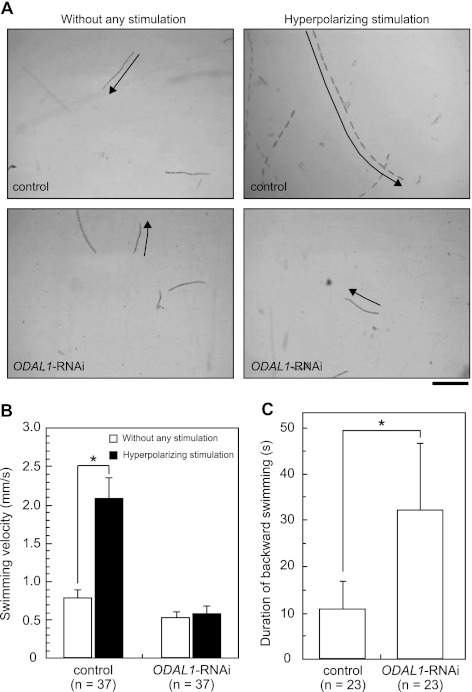

Phenotypes of ODAL1-silenced cells.

We examined the phenotypes of ODAL1-silenced (ODAL1-RNAi) cells. Control cells swam at approximately 0.8 mm/s and showed a significant increase in the forward swimming velocity in response to hyperpolarizing stimulation by the addition of CaCl2 to attain a Ca2+ concentration of 2 mM (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, ODAL1-RNAi cells swam at half the swimming velocity of the control cells. Moreover, ODAL1-RNAi cells did not show a significant increase in the forward swimming velocity in response to hyperpolarizing stimulation (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig 3.

Phenotypes of ODAL1-RNAi cells. Swimming behaviors of control cells and ODAL1-RNAi cells (2 days after the induction of gene silencing) were observed under certain conditions. Observation and recording were performed as indicated in Materials and Methods. (A) Swimming paths of live paramecia for 1 s without any stimulation and in response to hyperpolarizing stimulation by the addition of CaCl2 to attain a Ca2+ concentration of 2 mM. The frame capture rate was 15 frames per s. The arrows indicate the swimming directions. Bar, 0.5 mm. (B) Forward swimming velocity in control cells and ODAL1-RNAi cells. In the case of the control, the difference between the swimming velocities under standard conditions and under conditions of hyperpolarizing stimulation was significant (∗, P < 0.01 by t test). In the case of ODAL1-RNAi cells, the difference was not significant. (C) Duration of backward swimming in control and ODAL1-RNAi cells. Backward swimming was induced by depolarizing stimulation by the addition of KCl to attain a K+ concentration of 50 mM. The difference between the durations of backward swimming in control and ODAL1-RNAi cells was significant (∗, P < 0.001 by t test). Boxes and bars indicate means ± standard deviations (SD), respectively. The number of measurements is indicated in each panel (B and C).

Control cells exhibited backward swimming for approximately 10 s in response to depolarizing stimulation by the addition of KCl to attain a K+ concentration of 50 mM. In contrast, ODAL1-RNAi cells exhibited a long period of backward swimming after the depolarizing stimulation (Fig. 3C). They also exhibited a short period of backward swimming (within 1 s), an “avoiding reaction,” frequently seen in culture medium without the depolarizing stimulant (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). The phenotypes of ND7-silenced (ND7-RNAi) cells were the same as those of the control cells (data not shown).

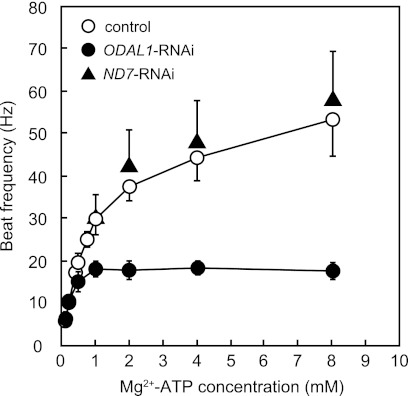

Effects of ODAL1 silencing on ciliary beat frequency in response to Mg2+-ATP.

The effects of ODAL1 silencing on the ciliary beat frequency were determined at various concentrations of Mg2+-ATP by using intact cortical sheets. The ciliary beat frequency of the control cells increased with increasing Mg2+-ATP concentrations up to 8 mM (Fig. 4, and see Movie S2A in the supplemental material). The apparent Km and Vmax were 0.80 mM and 52 Hz, respectively. In contrast, the ciliary beat frequency of ODAL1-RNAi cells did not increase in the presence of ≥1 mM Mg2+-ATP (Fig. 4, and see Movie S2B in the supplemental material). The apparent Km and Vmax of ODAL1-RNAi cells (2 days after the induction of gene silencing) were 0.22 mM and 21 Hz, respectively. However, the reactivated cilia of ODAL1-RNAi cells showed a normal beat cycle that consisted of an effective stroke and a recovery stroke (37) (see Movie S2B in the supplemental material). The ciliary beat frequency of ND7-RNAi cells was essentially the same as that of the control (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Effect of ODAL1 silencing on ciliary beat frequency in response to Mg2+-ATP. Changes in the ciliary beat frequency in response to an increasing Mg2+-ATP concentration were determined. Intact cortical sheets from control cells, ODAL1-RNAi cells (2 days after the induction of gene silencing), and ND7-RNAi cells (2 days after the induction of gene silencing) were perfused successively with reactivation solutions containing 5 μM cGMP, 1 mM EGTA, 50 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM Tris-maleate buffer (pH 7.0), and various concentrations of Mg2+-ATP. The MgCl2 concentration was kept at 1 mM at an ATP concentration of ≤1 mM. The MgCl2 concentration was equal to the ATP concentration at an ATP concentration of >1 mM. Values represent means ± SD (n = 5 to 13).

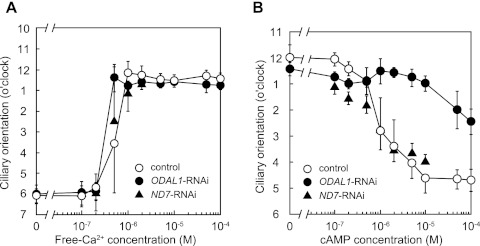

Effects of ODAL1 silencing on ciliary orientation in response to Ca2+ and cAMP.

The effects of ODAL1 silencing on the ciliary orientation in response to Ca2+ without cAMP were determined by using cortical sheets. The orientation of the reactivated cilia of the control was toward the 6-o'clock position (posterior direction of the cell) at ≤0.2 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 5A). When the cortical sheets were perfused with a reactivation solution containing ≥1 μM Ca2+, the orientation of the cilia was toward the 12-o'clock position (anterior direction of the cell) (26, 28, 29). The changes in the ciliary orientation of ODAL1-RNAi cells on cortical sheets in response to Ca2+ were very similar to those of the control cells (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5.

Effects of ODAL1 silencing on ciliary orientation in response to Ca2+ and cAMP. The ciliary orientation in response to Ca2+ and cAMP was determined in the presence of 30% glycerol. The demembranated cortical sheets from control, ODAL1-RNAi (2 days after the induction of gene silencing), and ND7-RNAi (2 days after the induction of gene silencing) cells were perfused successively with reactivation solutions containing 30% glycerol, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM potassium acetate, and 10 mM Tris-maleate buffer (pH 7.0) and various concentrations of free Ca2+ and cAMP, as noted in the abscissas. The free Ca2+ concentration in the reactivation solutions was controlled as indicated in Materials and Methods. The orientation between 11 o'clock and 2 o'clock indicates a Ca2+-induced ciliary reversal. (A) Changes in ciliary orientation in response to Ca2+ without cAMP. (B) Changes in ciliary orientation in response to cAMP in the presence of 2 μM Ca2+. Values represent means ± SD (n = 5 to 6).

The effects of ODAL1 silencing on the ciliary orientation on cortical sheets in response to cAMP were determined in the presence of 2 μM Ca2+. In the case of the control cells, the ciliary orientation began to change from an anterior to a posterior direction of the cell in the presence of 1 μM cAMP. At ≥10 μM cAMP, the orientation of the reactivated cilia was toward the 5-o'clock position (posterior direction of the cell). On the contrary, the ciliary orientation of ODAL1-RNAi cells did not change from the anterior to the posterior direction of the cell, even in the presence of 100 μM cAMP (Fig. 5B). The ciliary orientation of ND7-RNAi cells in response to Ca2+ and cAMP was essentially the same as that of control cells (Fig. 5A and B).

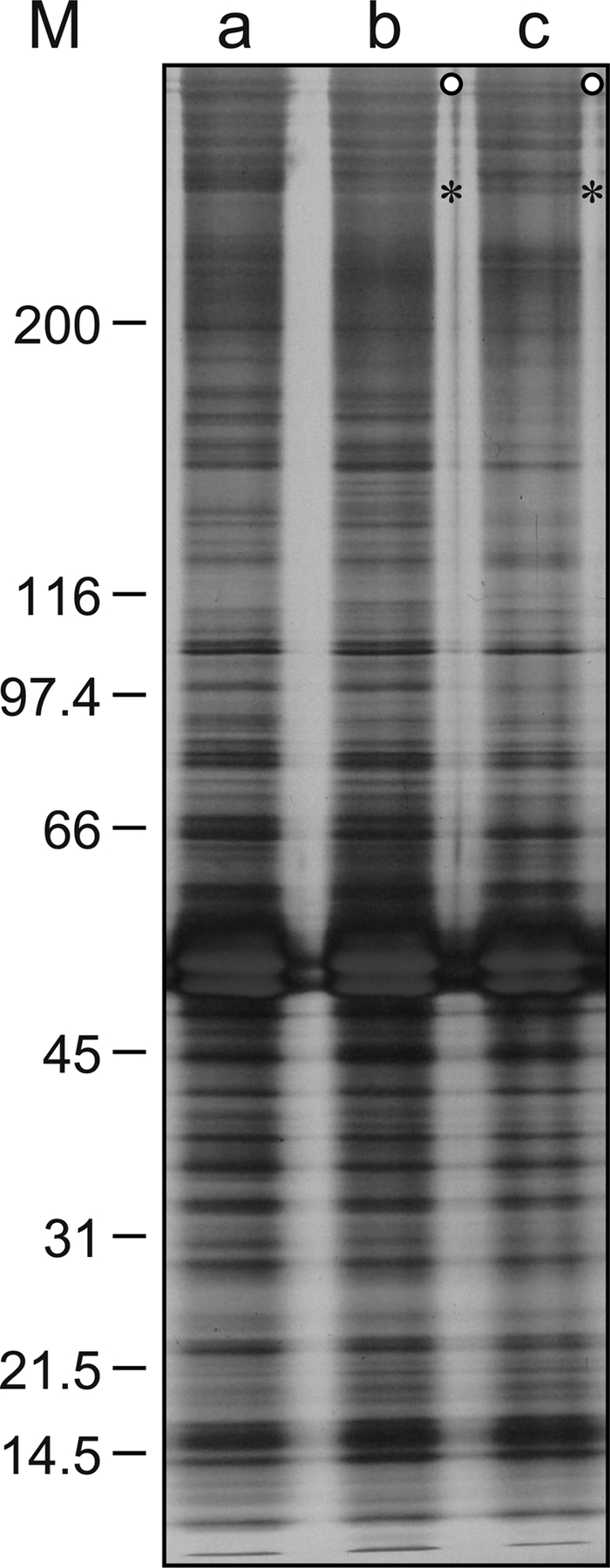

Change in composition of axonemal proteins after ODAL1 silencing.

The axonemal proteins of ODAL1-RNAi cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 3-to-15% polyacrylamide gradient gels. The two HC bands were decreased to some extent in the 1-day- and 2-day-silenced ODAL1-RNAi cells (Fig. 6, lanes b and c). The composition of axonemal proteins was not affected by ND7 silencing (data not shown).

Fig 6.

SDS-PAGE patterns of axonemal proteins from ODAL1-RNAi cells. The compositions of axonemal proteins from control (lane a), ODAL1-RNAi (1 day after the induction of gene silencing) (lane b), and ODAL1-RNAi (2 days after the induction of gene silencing) (lane c) cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described in Materials and Methods. Open circles, outer dynein arm HCs; asterisks, an unidentified HC; M, Mr of markers (×103).

Effects of ODAL1 silencing on cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of axonemal proteins.

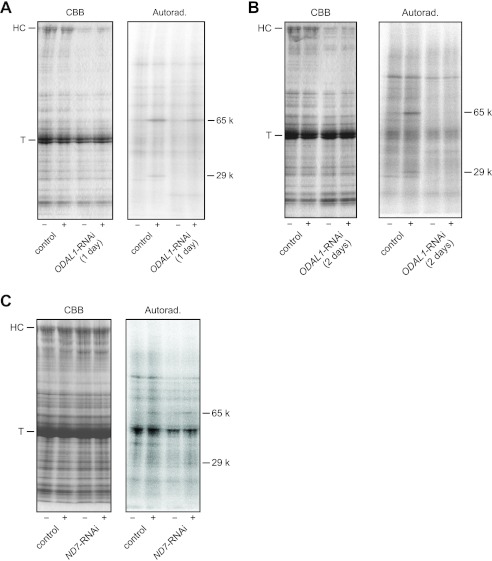

We examined the effects of ODAL1 silencing on the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of axonemal proteins. In control and the ND7-RNAi cells, the 29-kDa and 65-kDa axonemal polypeptides were phosphorylated with 10 μM cAMP (5, 17, 26, 27, 29, 30) (Fig. 7).

Fig 7.

cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of the axonemal proteins from ODAL1-RNAi cells. Axonemes were labeled in vitro with adenosine 5′-[γ-32P]triphosphate. The phosphorylated proteins were run on 3-to-15% linear gradient acrylamide gels. CBB, band pattern stained with Coomassie blue R 250; Autorad., autoradiogram. (A) Effect of ODAL1 silencing (1 day after the induction of gene silencing) on the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of axonemal proteins. (B) Effects of ODAL1 silencing (2 days after the induction of gene silencing) on the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of axonemal proteins. (C) Effects of ND7 silencing on the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of axonemal proteins. 65 k and 29 k indicate the cAMP-dependent phosphorylated 65-kDa and 29-kDa polypeptides in the autoradiogram, respectively. + and − indicate the presence and absence of 10 μM cAMP, respectively. HC, outer dynein arm HCs; T, tubulins.

In ODAL1-RNAi cells, the 65-kDa polypeptide was phosphorylated with 10 μM cAMP, but the phosphorylation of the 29-kDa polypeptide was not detected after 1 day of silencing (Fig. 7A). After 2 days of silencing, no phosphorylation was detected for the 29-kDa or 65-kDa polypeptide (Fig. 7B).

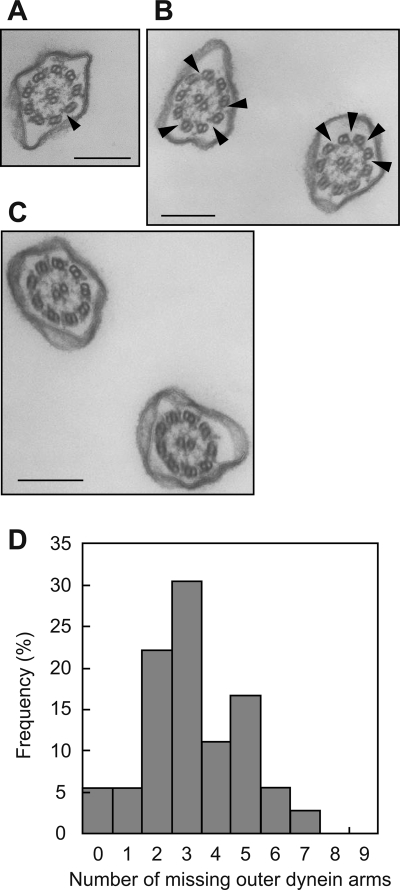

Effects of ODAL1 silencing on the presence of outer and inner dynein arms within axonemes.

Cross sections of cilia from the control, ODAL1-RNAi, and ND7-RNAi cells were observed by using a transmission electron microscope. In the ODAL1-RNAi axonemes, a couple of the outer dynein arms had disappeared randomly (indicated by arrowheads in Fig. 8A and B). The mean number of missing outer dynein arms was 3.22 ± 1.64 (n = 36) (Fig. 8D). However, the inner dynein arms of ODAL1-RNAi were not affected. In the ND7-RNAi cells, both the outer and inner dynein arms were not affected (Fig. 8C).

Fig 8.

Transmission electron micrographs of cross sections of ODAL1-RNAi cilia. Typical cross-sectional images of cilia from ODAL1-RNAi (2 days after the induction of gene silencing) (A and B) and ND7-RNAi (C) cells were observed by using a transmission electron microscope. The arrowheads indicate the positions of the missing outer dynein arms on the outer doublet microtubules. Bars, 200 nm. (D) Histogram of missing outer dynein arms in ODAL1-RNAi axonemes. The abscissa indicates how many outer dynein arms were missing (n = 36).

DISCUSSION

Outer dynein arm LC1 has been thought to be responsible for regulating ciliary and flagellar movements. For example, C. reinhardtii LC1 binds the outer arm dynein γHC motor domain and a doublet microtubule within the axonemal superstructure and may regulate outer dynein arm activity through a conformational switch for flagellar motility (8, 33, 45). In T. brucei, LC1 is necessary for proper forward flagellar motility and for a stable outer dynein arm assembly (6). LC1 of the planarian S. mediterranea acts in a mechanosensory feedback mechanism controlling outer arm activity (36). However, the role of outer dynein arm LC1 in the molecular mechanisms of ciliary and flagellar movements is unclear. In this study, we cloned ODAL1 from P. tetraurelia using the Paramecium genome database and the ciliary proteome database (1–4). To clarify the role of ODAL1 in the ciliary movements of P. tetraurelia, we created ODAL1-silenced cells by RNAi using the feeding method (14) and examined the effects of ODAL1 silencing on the ciliary movements and the compositions of axonemal proteins. We confirmed that the ODAL1 gene was properly silenced (Fig. 2) and that ODAL1 silencing could have no off-target effects. Furthermore, as a negative control, we examined the effects of ND7 silencing, which affects trichocyst exocytosis without altering the ODAL1 gene or any other cellular function (16, 37). We confirmed that ND7 silencing did not affect the ciliary movements and the compositions of axonemal proteins (Fig. 4, 5, 7C, and 8C).

We initially examined the phenotypes of ODAL1-RNAi cells. They swam more slowly than the control cells, and their swimming velocity did not increase in response to hyperpolarizing stimulation (Fig. 3A and B). In addition, the silenced cells showed a long period of backward swimming in response to depolarizing stimulation and, frequently, a spontaneous avoiding reaction in the absence of depolarizing stimulation (Fig. 3C, and see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). These observations suggest that ODAL1 silencing resulted in two types of defects in the ciliary activities. The first defect is the impairment of the ability to increase the ciliary beat frequency. The second defect is apparent hypersensitivity to Ca2+.

The ciliary beat frequency depends on the Mg2+-ATP concentration (31) (Fig. 4, and see Movie S2A in the supplemental material). We found that the ciliary beat frequency on intact cortical sheets of ODAL1-RNAi cells did not increase with high concentrations of Mg2+-ATP (≥1 mM) (Fig. 4, and see Movie S2B in the supplemental material). This indicates that ODAL1 silencing impairs the ability to increase the ciliary beat frequency. Therefore, the slow swimming of ODAL1-RNAi cells (Fig. 3A and B) is a consequence of the impairment of the ability to increase the ciliary beat frequency. The reactivated cilia of ODAL1-RNAi cells showed a normal beat cycle that consisted of an effective stroke and a recovery stroke (41) (see Movie S2B in the supplemental material). This suggests that ODAL1 silencing does not impair the ciliary waveform. In C. reinhardtii and Tetrahymena thermophila, an inner dynein arm has been thought to be responsible for the regulation of the ciliary and flagellar waveforms (12, 44). Therefore, the normal ciliary waveform in ODAL1-RNAi cells indicates that ODAL1 silencing does not affect the inner dynein arms of Paramecium (Fig. 8).

Previous analyses of ciliary movements using permeabilized cell models (Triton models) and cortical sheets have shown that ≥1 μM Ca2+ induces a ciliary reversal and backward swimming (11, 24–30). We expected that if ODAL1-RNAi cells showed hypersensitivity to Ca2+, the ciliary orientation on cortical sheets would show a ciliary reversal in the presence of lower Ca2+ concentrations compared with that of the control cells. However, the threshold Ca2+ concentration for the ciliary orientation reversal of the control cells was almost similar to that of ODAL1-RNAi cells (Fig. 5A). This indicates that ODAL1 silencing does not affect sensitivity to Ca2+ in the ciliary motor mechanism.

cAMP makes the ciliary orientation more posterior (26, 27, 29). Furthermore, it was shown previously that cAMP and Ca2+ act antagonistically in setting the ciliary orientation and that cAMP suppresses Ca2+-induced ciliary reversal (11, 25–30). We analyzed the effect of ODAL1 silencing on cAMP-dependent ciliary responses using cortical sheets. As shown in Fig. 5B, the ciliary reversal induced by 2 μM Ca2+ was not suppressed by cAMP in cortical sheets of ODAL1-RNAi cells. This result indicates that ODAL1 silencing impairs the ciliary response to cAMP. Therefore, the phenotypes of ODAL1-RNAi cells, such as the longer period of backward swimming (Fig. 3C) and the spontaneous avoiding reaction in the absence of any stimulation (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material), are probably due to the apparent hypersensitivity to Ca2+ that is a consequence of the defect in the ciliary response to cAMP.

To test whether ODAL1 silencing affects axonemal proteins other than the ODAL1 product, we analyzed the composition of axonemal proteins in ODAL1-RNAi cells using SDS-PAGE. In the axonemes of ODAL1-RNAi cells, two HC bands (>200 kDa) were decreased to some extent (Fig. 6, lane b). The upper band corresponds to the outer dynein arm HC (indicated by open circles in Fig. 6). In addition, after 2 days of silencing, several bands of the axonemal proteins also decreased (Fig. 6, lane c). We observed the cross-sectional images of the ODAL1-RNAi axonemes with missing outer dynein arms at the level where inner dynein arms were present (Fig. 8). While such defects were rare, we did not see such axoneme cross sections in nonsilenced cells and in ND7-RNAi cells. Our observations indicate that as previously shown for T. brucei (6), in P. tetraurelia, the loss of ODAL1 also destabilizes the outer dynein arms.

In Paramecium, a 29-kDa polypeptide (p29), an LC of the outer dynein arm (22S dynein), is phosphorylated in a cAMP-dependent manner (5, 17, 26, 27, 29, 30) (Fig. 7A and B). The sliding velocity between the outer dynein arm containing p29 and the outer doublet microtubules increased in a cAMP-dependent manner (5, 17). Therefore, p29 is thought to play a key role in ciliary movements in response to cAMP. The deduced amino acid sequence of ODAL1 includes several phosphorylation sites (Fig. 1), and the ciliary orientation on cortical sheets from ODAL1-RNAi cells lost cAMP-dependent control (Fig. 5B). This may be due to the absence of the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of some axonemal proteins induced by ODAL1 silencing. To test this possibility, we examined the effects of ODAL1 silencing on the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of axonemal proteins. As a result, the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of p29 was not detected in the axonemes from ODAL1-RNAi cells (Fig. 7A and B). This result indicates that ODAL1 silencing impairs the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of p29. The SDS-PAGE band pattern and the observation of cross-sectional images of the ODAL1-RNAi axonemes showed that the outer dynein arms were decreased to some extent (Fig. 6 and 8). These results suggest that the defect in the ciliary response to cAMP caused by ODAL1 silencing may be due to a reduction in the levels of p29 in the outer dynein arm. Our results also suggest that the structural integrity of the outer dynein arm may be essential to produce a high ciliary beat frequency. Further studies, e.g., determining ciliary movements using gene silencing for the other outer dynein arm components, will be required to clarify the mechanisms regulating the ciliary beat frequency.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the ODAL1 gene is essential for controlling the ciliary response by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. The ODAL1 product may be the p29-phosphorylatable LC of the Paramecium 22S dynein. The use of gene silencing by RNAi using the feeding method and the analysis of ciliary movements using cortical sheets could provide further information for an understanding of the molecular mechanism of ciliary movements.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (C) from MEXT of Japan (grant no. 21590358 to M.H.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 March 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arnaiz O, Sperling L. 2011. ParameciumDB in 2011: new tools and new data for functional and comparative genomics of the model ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D632–D636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnaiz O, Cain S, Cohen J, Sperling L. 2007. ParameciumDB: a community resource that integrates the Paramecium tetraurelia genome sequence with genetic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D439–D444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnaiz O, et al. 2009. Cildb: a knowledgebase for centrosomes and cilia. Database 2009:bap022 doi: 10.1093/database/bap022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aury JM, et al. 2006. Global trends of whole-genome duplications revealed by the ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia. Nature 444:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barkalow K, Hamasaki T, Satir P. 1994. Regulation of 22S dynein by a 29-kD light chain. J. Cell Biol. 126:727–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baron DM, Kabututu ZP, Hill KL. 2007. Stuck in reverse: loss of LC1 in Trypanosoma brucei disrupts outer dynein arms and leads to reverse flagellar beat and backward movement. J. Cell Sci. 120:1513–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becker-André M, Hahlbrock K. 1989. Absolute mRNA quantification using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A novel approach by a PCR aided transcript titration assay (PATTY). Nucleic Acids Res. 17:9437–9446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benashski SE, Patel-King RS, King SM. 1999. Light chain 1 from the Chlamydomonas outer dynein arm is a leucine-rich repeat protein associated with the motor domain of the γ heavy chain. Biochemistry 38:7253–7264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. 1999. Sequence- and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J. Mol. Biol. 294:1351–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blum H, Beier H, Gross HJ. 1987. Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis 8:93–99 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonini NM, Nelson DL. 1988. Differential regulation of Paramecium ciliary motility by cAMP and cGMP. J. Cell Biol. 106:1615–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brokaw CJ, Kamiya R. 1987. Bending patterns of Chlamydomonas flagella. IV. Mutants with defects in inner and outer dynein arms indicate differences in dynein arm function. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 8:68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eckert R. 1972. Bioelectric control of ciliary activity. Science 176:473–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Galvani A, Sperling L. 2002. RNA interference by feeding in Paramecium. Trends Genet. 18:11–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilliland G, Perrin S, Blanchard K, Bunn HF. 1990. Analysis of cytokine mRNA and DNA, detection and quantitation by competitive polymerase chain reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:2725–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gogendeau D, et al. 2008. Functional diversification of centrins and cell morphological complexity. J. Cell Sci. 121:65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamasaki T, Barkalow K, Richmond J, Satir P. 1991. cAMP stimulated phosphorylation of an axonemal polypeptide that copurifies with the 22S dynein arm regulates microtubule translocation velocity and swimming speed in Paramecium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:7918–7922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hamasaki T, Murtaugh TJ, Satir BH, Satir P. 1989. In vitro phosphorylation of Paramecium axonemes and permeabilized cells. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 12:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. King SM, Kamiya R. 2008. Axonemal dyneins: assembly, structure and force generation, p 131–208. In Witman GB. (ed), The Chlamydomonas sourcebook: cell motility and behavior, vol 3 Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lowry OH, Rowebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Machemer H. 1988. Electrophysiology, p 185–215. In Görtz HD. (ed), Paramecium. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mogami Y, Takahashi K. 1983. Calcium and microtubule sliding in ciliary axonemes isolated from Paramecium caudatum. J. Cell Sci. 61:107–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naitoh Y, Kaneko H. 1972. Reactivated Triton-extracted models of Paramecium: modification of ciliary movement by calcium ions. Science 176:523–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakaoka Y, Ooi H. 1985. Regulation of ciliary reversal in Triton-extracted Paramecium by calcium and cyclic adenosine monophosphate. J. Cell Sci. 77:185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noguchi M, Kitani T, Ogawa T, Inoue H, Kamachi H. 2005. Augmented ciliary reorientation response and cAMP-dependent protein phosphorylation induced by glycerol in Triton-extracted Paramecium. Zool. Sci. 22:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Noguchi M, Kurahashi S, Kamachi H, Inoue H. 2004. Control of the ciliary beat by cyclic nucleotides in the intact cortical sheets from Paramecium. Zool. Sci. 21:1167–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Noguchi M, Nakamura Y, Okamoto K-I. 1991. Control of ciliary orientation in ciliated sheets from Paramecium—differential distribution of sensitivity to cyclic nucleotides. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 20:38–46 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Noguchi M, Ogawa T, Taneyama T. 2000. Control of ciliary orientation through cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of axonemal proteins in Paramecium caudatum. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 45:263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noguchi M, Sasaki J, Kamachi H, Inoue H. 2003. Protein phosphatase 2C is involved in the cAMP-dependent ciliary control in Paramecium caudatum. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 54:95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Noguchi M, Sawada T, Akazawa T. 2001. ATP-regenerating system in the cilia of Paramecium caudatum. J. Exp. Biol. 204:1063–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noonan KE, et al. 1990. Quantitative analysis of MDR1 (multidrug resistance) gene expression in human tumors by polymerase chain reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:7160–7164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel-King RS, King SM. 2009. An outer arm dynein light chain acts in a conformational switch for flagellar motility. J. Cell Biol. 186:283–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Portzehl H, Caldwell PC, Rüegg JC. 1964. The dependence of contraction and relaxation of muscle fibers from the crab Maia squinado on the internal concentration of free calcium ions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 79:581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reynolds ES. 1963. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 17:208–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rompolas P, Patel-King RS, King SM. 2010. An outer arm dynein conformational switch is required for metachronal synchrony of motile cilia in planaria. Mol. Biol. Cell 21:3669–3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ruiz F, Vayssié L, Klotz C, Sperling L, Madeddu L. 1998. Homology-dependent gene silencing in Paramecium. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:931–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schultz JE, Klumpp S, Benz R, Schürhoff-Goeters WJ, Schmid A. 1992. Regulation of adenylyl cyclase from Paramecium by an intrinsic potassium conductance. Science 255:600–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Siebert PD, Larrick JW. 1992. Competitive PCR. Nature 359:557–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sonneborn TM. 1970. Methods in Paramecium research, p 241–339. In Prescott D. (ed), Methods in cell physiology, vol 4 Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sugino K, Naitoh Y. 1982. Simulated cross-bridge patterns corresponding to ciliary beating in Paramecium. Nature 295:609–611 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A. 2001. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 263:103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Watson ML. 1958. Staining of tissue sections for electron microscopy with heavy metals. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 4:475–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wood CR, Hard R, Hennessey TM. 2007. Targeted gene disruption of dynein heavy chain 7 of Tetrahymena thermophila results in altered ciliary waveform and reduced swim speed. J. Cell Sci. 120:3075–3085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu H, et al. 2000. Solution structure of a dynein motor domain associated light chain. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:575–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.