Abstract

A total of 47 extended-spectrum-cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli strains isolated from stray dogs in 2006 and 2007 in the Republic of Korea were investigated using molecular methods. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and AmpC β-lactamase phenotypes were identified in 12 and 23 E. coli isolates, respectively. All 12 ESBL-producing isolates carried blaCTX-M genes. The most common CTX-M types were CTX-M-14 (n = 5) and CTX-M-24 (n = 3). Isolates producing CTX-M-3, CTX-M-55, CTX-M-27, and CTX-M-65 were also identified. Twenty-one of 23 AmpC β-lactamase-producing isolates were found to carry blaCMY-2 genes. TEM-1 was associated with CTX-M and CMY-2 β-lactamases in 4 and 15 isolates, respectively. In addition to blaTEM-1, two isolates carried blaDHA-1, and one of them cocarried blaCMY-2. Both CTX-M and CMY-2 genes were located on large (40 to 170 kb) conjugative plasmids that contained the insertion sequence ISEcp1 upstream of the bla genes. Only in the case of CTX-M genes was there an IS903 sequence downstream of the gene. The spread of ESBLs and AmpC β-lactamases occurred via both horizontal gene transfer, accounting for much of the CTX-M gene dissemination, and clonal spread, accounting for CMY-2 gene dissemination. The horizontal dissemination of blaCTX-M and blaCMY-2 genes was mediated by IncF and IncI1-Iγ plasmids, respectively. The clonal spread of blaCMY-2 was driven mainly by E. coli strains of virulent phylogroup D lineage ST648. To our knowledge, this is the first report of blaDHA-1 in E. coli strains isolated from companion animals. This study also represents the first report of CMY-2 β-lactamase-producing E. coli isolates from dogs in the Republic of Korea.

INTRODUCTION

The main mechanism of acquired resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) in Enterobacteriaceae is the production of plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and/or AmpC β-lactamases (pAmpCs) (1). CTX-M β-lactamases, a new group of plasmid-mediated ESBLs, were first reported from Japan in 1986 (21). However, since 2000, CTX-M β-lactamases have increasingly been reported in both human and animal populations and are now the dominant type of ESBL, replacing classical TEM- and SHV-type ESBLs in most areas of the world (33). Currently, there are >120 different CTX-M β-lactamases that are clustered into five groups (CTX-M-1, -2, -8, -9, and -25), and among them, the members of the CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-9 clusters have repeatedly been reported for Enterobacteriaceae from the Republic of Korea (10, 18, 40).

AmpC β-lactamases can be either chromosomal or plasmid mediated. Constitutive overexpression of pAmpC genes located in plasmids mediates resistance to ESCs in species without their own ampC gene or with low-level expression of the intrinsic ampC gene (29). The first pAmpC gene, the CMY-1 gene, was reported in 1989 (3). Since then, various types of pAmpCs have been isolated from clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae around the world (30). In the Republic of Korea, pAmpCs have increasingly been detected, and in a study carried out between October 2008 and July 2009 among patients of 68 long-term care facilities nationwide, DHA-1 was detected in 39.3% of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates and DHA-1, CMY-2, and CMY-6 were identified in 3.1% of Escherichia coli isolates (43).

Companion animals such as dogs play an important role in the exchange of antimicrobial resistance determinants in bacterial populations, since they are exposed to antimicrobial agents (for treatment) similar to those used for humans. They also share the same environment as humans and remain in close contact with them (10, 27). Moreover, transmission of resistant bacteria or mobile resistance determinants between companion animals and humans has been documented (14, 36). Since the first detection of an ESBL in an E. coli isolate from a laboratory dog in Japan in 1998 (21), a variety of ESBLs, including CTX-M-type ESBLs, and pAmpCs have been reported for bacteria derived from dogs, cats, and other companion animals worldwide. Thus, such bacterial strains may provide a reservoir for ESBL- and/or pAmpC-producing bacteria for humans (5, 26, 35). A further worrying development is that highly virulent human pandemic B2-O25:H4-ST131 CTX-M-15-producing E. coli strains were recently isolated from companion animals belonging to different species in various European countries (12, 31). The possibility of interspecies transmission of these multiresistant strains from humans to companion animals and vice versa is a matter of great public health concern.

Recently, we reported ESC resistance among fecal E. coli isolates from stray and hospitalized companion dogs from the Republic of Korea (24) and hypothesized that ESBL and/or pAmpC genes would be present in isolates from dogs in the Republic of Korea. However, to date, the only report of an ESBL detected in isolates from dogs has been the identification of blaCTX-M-14 in an E. coli isolate from a sick dog by our research group (20). Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the presence of ESBL and/or pAmpC genes among E. coli isolates recovered from intestinal samples of stray dogs that had been collected throughout the Republic of Korea between 2006 and 2007 and to subsequently characterize positive isolates by using molecular methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 628 E. coli isolates recovered from 877 intestinal samples from stray (422 isolates) and hospitalized (206 isolates) dogs during 2006 and 2007 were investigated. The collection of intestinal samples and isolation, identification, and phenotypic characterization of E. coli isolates were described extensively in our previous report (24). Among the isolates collected, E. coli isolates showing resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins were further characterized with regard to ESBL and pAmpC enzymes in this study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by the standard disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (8). MICs of selected antimicrobials were determined by Etest methodology (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) according to CLSI guidelines (8). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as quality control strains for MIC tests.

Phenotypic detection of ESBL production was performed by a double-disc synergy test and was confirmed by the Etest method, using cefotaxime–cefotaxime-clavulanic acid and ceftazidime–ceftazidime-clavulanic acid strips (AB Biodisk) according to CLSI guidelines (8). Similarly, Etest for AmpC detection was employed for phenotypic confirmation of plasmid-mediated AmpC production, using cefotetan–cefotetan-cloxacillin strips (AB Biodisk) in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines.

Characterization of genes encoding β-lactamases.

PCR amplification and sequencing of the entire blaTEM and blaSHV genes were done as described previously (32). The presence of blaCTX-M β-lactamase genes was screened as described previously (2). For CTX-M-positive isolates, the blaCTX-M group-specific primers for CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-9 were used to confirm the presence of blaCTX-M genes (4). Finally, the combination of the CTX-M-1 or CTX-M-9 group forward primer and the ISECP1U1 primer (34) was used to amplify and sequence the complete blaCTX-M genes. Screening for genes encoding six families of pAmpCs was performed for cefoxitin-resistant isolates by use of multiplex PCR assays (28). For amplification of the entire blaAMPC gene, PCR-positive isolates were reamplified by use of specific primers as described previously (28). For isolates that did not contain a mobile pAmpC gene, chromosomal ampC promoter mutations were examined by PCR and sequencing (9). Sequence analyses and comparison with known sequences were performed with the BLAST programs at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Conjugation experiments.

Conjugation experiments were performed using sodium azide-resistant E. coli J53 as a recipient (38). Transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar plates supplemented with sodium azide (150 mg/liter) (Sigma) and cefotaxime (2 mg/liter) or cefoxitin (32 mg/liter). The transconjugants were examined for the presence of β-lactamase genes and tested for susceptibility as described above for the wild strains.

Plasmid replicon typing.

Plasmid DNAs were isolated using the QuickGene plasmid kit S II plasmid isolation system (Fujifilm Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid size was estimated by comparison with the BAC Tracker supercoiled DNA ladder (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) after gel electrophoresis in a 0.8% agarose gel. Plasmid replicon typing was done by a PCR-based method using 18 pairs of primers as described previously (6).

Southern hybridization.

Plasmid DNAs were blotted onto positively charged nylon membranes (Bio-Rad) by the capillary transfer method and were hybridized with probes specific for the blaCTX-M-9 cluster or the blaCMY-2 gene. PCR products amplified using primers CTX-M-9-F and CTX-M-9-R (4) and primers CMY-2-F and CMY-2-R (28) were used for the preparation of CTX-M-9- and CMY-2-specific probes, respectively. Probe labeling, hybridization, and detection were performed with a DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit I (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) following the manufacturer's protocols.

Analysis of genetic environment of blaCTX-M/CMY-2 genes.

The genetic environment of blaCTX-M/CMY-2 genes was investigated by PCR and sequencing. An ISEcp1 forward primer (34) and the CTX-M consensus reverse primer (34) or CMY-2 reverse primer (28) were used to investigate regions upstream of the bla genes. The CTX-M consensus forward primer (34) or CMY-2 forward primer (28) and the reverse primer for IS903, tnpA IS903, orf477, or mucA (11) were used to characterize regions downstream of the bla genes.

Phylogenetic grouping and ST determination.

The major phylogenetic group of each E. coli strain was determined by multiplex PCR (7). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was carried out as previously described (41). PCR amplification and sequencing of seven conserved housekeeping genes were performed using previously described primer sets for adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, and purA (41) and for mdh and recA (25). Allelic profile and sequence type (ST) determinations were done according to the E. coli MLST website (http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Ecoli) scheme.

PFGE.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of XbaI (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan)-digested genomic DNA was carried out according to the CDC pulseNet standardized procedure (13), using a Chef Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The similarities of the restriction fragment length polymorphisms were analyzed using Bionumerics software, version 4.0 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium), to produce a dendrogram. Clustering was carried out by the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA), based on the Dice similarity index.

RESULTS

Among 628 canine E. coli isolates examined, 18 and 29 of them were resistant to cefotaxime and cefoxitin, respectively. Of the 18 E. coli isolates resistant to cefotaxime, a positive confirmatory test for the production of ESBLs was observed for only 12 of them. The characteristics of these 12 E. coli isolates are presented in Table 1. Similarly, a phenotypic confirmatory test confirmed the production of AmpC β-lactamases in 23 of the 29 cefoxitin-resistant E. coli isolates.

Table 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of blaCTX-M-positive E. coli isolates from stray dogs in the Republic of Koreaa

| Strain | Etest MIC (mg/liter)b |

bla gene product |

Self-transferc |

blaCTX-M environment |

Non-β-lactam resistance pattern | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATM | FEP | CTX | CTX-CA | CAZ | CAZ-CA | CTX-M | Other | Upstream | Downstream | |||

| E-6 | 0.75 | 1.5 | 16 | 0.023 | <0.5 | 0.064 | CTX-M-3 | TEM-1 | − | ND | ND | |

| E-33 | 16 | 6 | >16 | 0.047 | 6 | 0.094 | CTX-M-55 | + | ISEcp1 | ND | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr | |

| E-102 | 6 | 1.5 | >16 | 0.064 | 1 | 0.125 | CTX-M-24 | + | ISEcp1 | IS903 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr | |

| E-120 | 16 | 24 | >16 | 0.125 | 6 | 0.125 | CTX-M-14 | + | ISEcp1 | IS903 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr | |

| E-121 | 16 | 3 | >16 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.25 | CTX-M-24 | TEM-1 | + | ISEcp1 | IS903 | GENr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-122 | 6 | 4 | >16 | 0.125 | 3 | 0.125 | CTX-M-27 | − | ISEcp1 | IS903 tnpA | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr | |

| E-123 | 3 | 4 | >16 | 0.094 | 0.75 | 0.125 | CTX-M-14 | + | ISEcp1 | IS903 | GENr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr | |

| E-124 | 4 | 1 | >16 | 0.032 | 1 | 0.064 | CTX-M-24 | − | ISEcp1 | IS903 | STRr TETr | |

| E-126 | 2 | 2 | >16 | 0.064 | 0.75 | 0.094 | CTX-M-14 | + | ISEcp1 | IS903 tnpA | GENr TETr AMKr | |

| E-127 | 4 | 1 | >16 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.094 | CTX-M-65 | − | ISEcp1 | IS903 tnpA | ||

| E-128 | 1.5 | 2 | >16 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.125 | CTX-M-14 | TEM-1 | + | ISEcp1 | IS903 tnpA | STRr TETr CHLr |

| E-129 | 0.5 | 1.5 | >16 | 0.023 | <0.5 | <0.064 | CTX-M-14 | TEM-1 | + | ISEcp1 | IS903 | GENr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

All isolates had positive double-disc diffusion test results. Abbreviations: ATM, aztreonam; FEP, cefepime; CTX, cefotaxime; CAZ, ceftazidime; CA, clavulanic acid; ND, not determined; IS903 tnpA, IS903 together with transposase gene; AMK, amikacin; GEN, gentamicin; STR, streptomycin; TET, tetracycline; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CHL, chloramphenicol; NAL, nalidixic acid; +, positive; −, negative.

All 12 blaCTX-M-positive E. coli isolates exhibited MICs of >256 and 1.5 to 6 mg/liter for ampicillin and cefoxitin, respectively.

Self-transfer of plasmid carrying blaCTX-M gene in conjugation experiments.

Characterization of ESBL and pAmpC genes.

All 12 ESBL-producing canine E. coli isolates carried blaCTX-M genes belonging to the CTX-M-1 (n = 2) or CTX-M-9 (n = 10) cluster. Sequencing of the entire blaCTX-M gene identified five isolates producing CTX-M-14, three isolates producing CTX-M-24, and one isolate each producing CTX-M-3, CTX-M-55, CTX-M-27, and CTX-M-65. Four of these blaCTX-M-positive isolates cocarried blaTEM-1, but none of them was positive for the blaSHV gene.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of canine E. coli isolates showing an AmpC resistance phenotype are shown in Table 2. Of the 23 AmpC β-lactamase-producing isolates, 21 carried a plasmid-borne CMY-2 gene. None of them harbored the blaSHV gene. Fifteen of 21 blaCMY-2-positive isolates also contained blaTEM-1. In addition to blaTEM-1, two isolates carried blaDHA-1, and one of these cocarried blaCMY-2. Sequencing of the ampC promoter region for one isolate that did not contain a plasmid-borne ampC gene identified substitutions at positions −32 (T → A) and +70 (C → T) in this strain compared with the ampC promoter sequence from E. coli K-12.

Table 2.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of blaCMY-2- and/or blaDHA-1-positive E. coli isolates from stray dogs in the Republic of Koreaa

| Strain |

bla gene product |

Self-transferc | Plasmid replicon type | Etest MIC (mg/liter) |

Non-β-lactam resistance pattern | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMY | Other(s) | FOX | CTT | CTT-CX | ||||

| E-008 | CMY-2 | + | F, FIB, I1-γ | 48 | 16 | <0.5 | TETr | |

| E-009 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB, I1-γ | >256 | >32 | 0.75 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-011 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB, I1-γ | >256 | >32 | 0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-012 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB, I1-γ | >256 | >32 | 0.75 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-013 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB, I1-γ | >256 | >32 | 0.75 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-028 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB, I1-γ | >256 | >32 | 0.5 | TETr NALr SXTr |

| E-040 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | + | F, FIA, FIB, I1-γ | 32 | 12 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr |

| E-044 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB | 64 | 16 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-045 | CMY-2 | + | I1-γ | >256 | >32 | <0.5 | ||

| E-099 | CMY-2 | TEM-1, DHA-1 | + | F, FIA, FIB, HI2 | 64 | <0.5 | <0.5 | |

| E-104 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB | 96 | 16 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-108 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB | 256 | >32 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-109 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB | 192 | >32 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-117 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | + | F, FIB, I1-γ | >256 | >32 | 0.5 | STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-118 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | + | FIA, FIB | >256 | >32 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr |

| E-119 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | + | HI1 | >256 | >32 | 4 | TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr |

| E-131 | CMY-2 | TEM-1 | + | FIA, FIB | 64 | >32 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr |

| E-132 | CMY-2 | + | F | 96 | >32 | <0.5 | ||

| E-133 | CMY-2 | + | F, P, I1-γ | 32 | 8 | <0.5 | STRr TETr | |

| E-134 | CMY-2 | + | A/C | 32 | 12 | <0.5 | STRr TETr SXTr CHLr | |

| E-136 | CMY-2 | − | A/C | 32 | 12 | <0.5 | STRr TETr SXTr CHL | |

| E-138 | TEM-1, DHA-1 | − | HI2 | 48 | <0.5 | <0.5 | GENr STRr TETr NALr SXTr CIPr CHLr | |

| E-139b | TEM-1 | − | F, FIA, FIB, I1-γ | 32 | 1.5 | <0.5 | ||

Abbreviations: FOX, cefoxitin; CTT, cefotetan; CX, cloxacillin; GEN, gentamicin; STR, streptomycin; TET, tetracycline; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CHL, chloramphenicol; NAL, nalidixic acid; CIP, ciprofloxacin; +, positive; −, negative.

Mutation analysis in the promoter and/or attenuator region identified changes at positions −32 (T → A) and +70 (C → T) in this strain compared with the ampC gene sequence from E. coli K-12.

Self-transfer of plasmid carrying blaCTX-M gene in conjugation experiments.

Conjugation experiments and plasmid analysis.

The transfer of the cefotaxime and cefoxitin resistance phenotypes to sodium azide-resistant E. coli J53 recipients by conjugation was demonstrated for 8 blaCTX-M- and 11 blaCMY-2-positive E. coli isolates, respectively. PCR analysis showed the presence of the respective blaCTX-M or blaCMY-2 gene in all transconjugants. However, the blaDHA-1 and/or blaTEM-1 gene did not transfer and was not amplified in the corresponding transconjugants. Resistance to non-β-lactam antimicrobials was also cotransferred in some cases, in addition to transfer of ESC resistance. The characteristics of E. coli J53 transconjugants carrying a blaCTX-M or blaCMY-2 gene are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of E. coli J53 transconjugants carrying blaCTX-M or blaCMY-2 genes described in this studya

| Transconjugant | Donor strain | Product of transferred bla gene | Plasmid bearing bla gene |

Conjugation frequency | Genetic environment of bla gene |

Resistance cotransferred | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (kb) | Inc type | Upstream | Downstream | |||||

| pE-033J | E-033 | CTX-M-55 | 70 | NID | 1.1 × 10−4 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr CEPr |

| pE-102J | E-102 | CTX-M-24 | 90 | F | 2.7 × 10−5 | ISEcp1 | IS903 | AMPr CEPr |

| pE-120J | E-120 | CTX-M-14 | 90 | N | 4.3 × 10−6 | ISEcp1 | IS903 | AMPr CEPr GENr TETr SXTr CHLr |

| pE-121J | E-121 | CTX-M-24 | 95 | F | 8.2 × 10−7 | ISEcp1 | IS903 | AMPr CEPr TETr |

| pE-123J | E-123 | CTX-M-14 | 80 | F | 6.1 × 10−4 | ISEcp1 | IS903 | AMPr CEPr |

| pE-126J | E-126 | CTX-M-14 | 120 | K | 3.6 × 10−6 | ISEcp1 | IS903 tnpA | AMPr CEPr |

| pE-128J | E-128 | CTX-M-14 | 140 | NID | 3.2 × 10−6 | ISEcp1 | IS903 tnpA | AMPr CEPr |

| pE-129J | E-129 | CTX-M-14 | 90 | F | 2.0 × 10−4 | ISEcp1 | IS903 | AMPr CEPr |

| pE-008J | E-008 | CMY-2 | 95 | I1- γ | 3.0 × 10−8 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-040J | E-040 | CMY-2 | 170 | I1-γ | 1.4 × 10−7 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr CIPr |

| pE-045J | E-045 | CMY-2 | 40 | NID | 2.7 × 10−4 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-099J | E-099 | CMY-2 | 40 | NID | 8.0 × 10−8 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-117J | E-117 | CMY-2 | 120 | I1-γ | 8.7 × 10−5 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-118J | E-118 | CMY-2 | 50 | NID | 2.4 × 10−4 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-119J | E-119 | CMY-2 | 50 | NID | 2.9 × 10−6 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-131J | E-131 | CMY-2 | 50 | NID | 1.0 × 10−7 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-132J | E-132 | CMY-2 | 50 | NID | 2.6 × 10−5 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-133J | E-133 | CMY-2 | 55 | F | 2.0 × 10−5 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

| pE-134J | E-134 | CMY-2 | 50 | A/C | 3.0 × 10−8 | ISEcp1 | ND | AMPr AMCr CEPr |

Abbreviations: NID, not identified; IS903 tnpA, IS903 together with transposase gene; ND, not determined; AMP, ampicillin; AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; CEP, cephalothin; GEN, gentamicin; TET, tetracycline; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

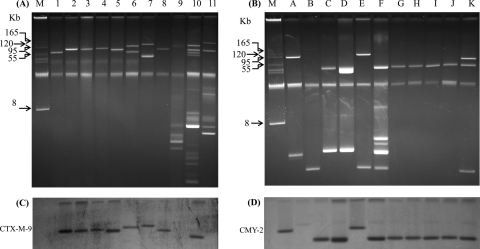

Plasmid DNA isolation from blaCTX-M-positive transconjugants revealed a large conjugative plasmid in each, ranging in size from 70 to 140 kb, except for in two transconjugants which apparently carried two large plasmids (Fig. 1A). Similarly, blaCMY-2-positive transconjugants revealed a large conjugative plasmid in each, ranging in size from 40 to 170 kb, apart from one or two smaller plasmids in some transconjugants (Fig. 1B). However, the wild canine E. coli strains demonstrated multiple plasmids of various sizes. The replicon typing data for the clinical isolates carrying blaCTX-M (data not shown) and blaCMY-2/DHA-1 (Table 2) revealed 10 and 8 different replicon types, respectively. Among these, 10 of 12 blaCTX-M-positive isolates and 16 of 22 blaCMY-2/DHA-1-positive isolates contained more than one type of replicon. Replicon type F was the most common replicon among both types of isolates. However, replicon typing of plasmids bearing a blaCTX-M or blaCMY-2 gene isolated from each transconjugant revealed only one replicon type (Table 3).

Fig 1.

Gel electrophoresis of plasmid DNAs extracted from blaCTX-M-positive transconjugants and selected donor E. coli strains (A) and from blaCMY-2-positive transconjugants (B). Southern hybridization was performed with probes specific for blaCTX-M-9 cluster genes (C) and the blaCMY-2 gene (D). Lanes: 1, pE-033J (lacking blaCTX-M-9 cluster gene); 2, pE-102J; 3, pE-120J; 4, pE-121J; 5, pE-123J; 6, pE-126J; 7, pE-128J; 8, pE-129J; 9, E-006 (lacking blaCTX-M-9 cluster gene); 10, E-124; 11, E-127; A, pE-008J; B, pE-040J; C, pE-045J; D, pE-099J; E, pE-117J; F, pE-118J; G, pE-119J; H, pE-131J; I, pE-132J; J, pE-133J; K, pE-134J; M, BAC Tracker supercoiled DNA marker.

Genetic localization of blaCTX-M and blaCMY-2 genes.

The blaCTX-M and blaCMY-2 genes in the plasmids isolated from all transconjugants and the blaCTX-M genes in three wild strains carrying these genes (for comparison) were localized by Southern hybridization. A probe specific for blaCTX-M-9 cluster genes hybridized with plasmids of various sizes carrying blaCTX-M-9 cluster genes but not with plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-1 cluster genes (transconjugant pE-033J and strain E-006) (Fig. 1C). Similarly, a blaCMY-2 gene-specific probe hybridized with a single large conjugative plasmid of variable size in all transconjugants carrying the blaCMY-2 gene (Fig. 1D).

Genetic environment of blaCTX-M and blaCMY-2 genes.

The insertion sequence ISEcp1 was identified upstream of all but one blaCTX-M gene in both the wild E. coli strains and their respective transconjugants. Furthermore, the insertion sequences IS903 and IS903 tnpA were detected downstream of the blaCTX-M genes in six and four E. coli strains, respectively, and in their transconjugants. Similarly, the blaCMY-2 gene detected in both the 21 wild donor strains and 11 corresponding transconjugants was preceded by ISEcp1. However, the genetic element downstream of the blaCMY-2 gene could not be determined at all.

Phylogenetic group and ST designation.

Phylogenetic analysis of E. coli isolates harboring blaCTX-M genes showed that five of them belonged to virulent groups B2 (n = 1) and D (n = 4) and seven belonged to avirulent groups B1 (n = 4) and A (n = 3). Similarly, analysis of E. coli isolates harboring blaCMY-2 genes revealed that 14 belonged to virulent groups B2 (n = 2) and D (n = 12) and 7 belonged to avirulent groups B1 (n = 6) and A (n = 1).

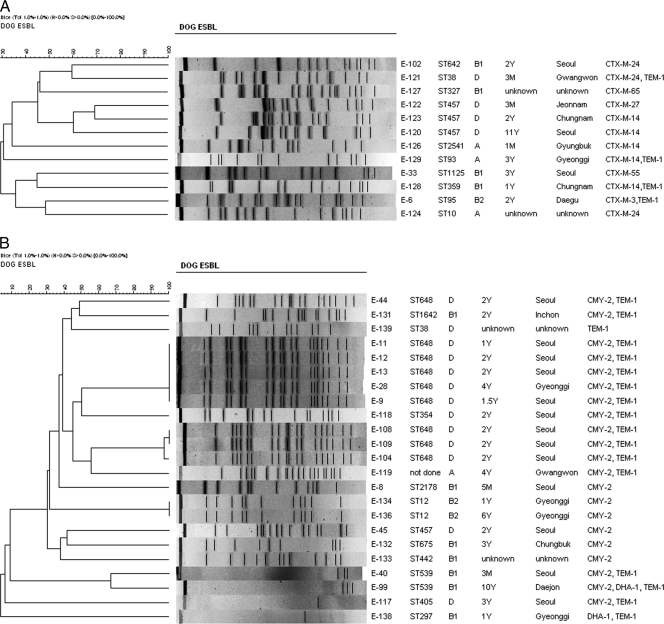

MLST analysis identified 10 unique STs among 12 E. coli isolates carrying blaCTX-M genes (Fig. 2A). These isolates were identified as ST10 (n = 1), ST38 (n = 1), ST93 (n = 1), ST95 (n = 1), ST327 (n = 1), ST359 (n = 1), ST457 (n = 3), ST642 (n = 1), ST1125 (n = 1), and ST2541 (n = 1) strains. Similarly, E. coli isolates carrying blaCMY-2 genes were identified as ST12 (n = 2), ST354 (n = 1), ST405 (n = 1), ST442 (n = 1), ST457 (n = 1), ST539 (n = 2), ST648 (n = 9), ST675 (n = 1), ST1642 (n = 1), and ST 2178 (n = 1) strains (Fig. 2B). Despite repeated attempts, the ST of one strain could not be determined.

Fig 2.

Dendrograms generated by Bionumerics software showing the cluster analysis of XbaI-PFGE patterns of CTX-M (A)- and CMY-2 (B)-producing E. coli strains isolated from stray dogs. Similarity analysis was performed by using the Dice coefficient, and clustering was done by the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UGPMA). For both the CTX-M- and CMY-2-producing strains, details given include the strain, sequence type of each strain, phylogenetic group of each strain, age of host dog, geographical origin of host dog, and bla genes carried by each strain. XbaI-macrorestriction analysis yielded a few or no DNA banding patterns for four E. coli strains due to autodegradation of the genomic DNA during agarose plug preparation, and thus a cluster formed by these strains was ignored throughout this paper. Abbreviations: M, month; Y, year.

PFGE analysis.

For finer resolution of the clonality of canine E. coli isolates carrying ESBL or pAmpC genes, molecular typing was done by PFGE of XbaI-digested genomic DNA. All 12 CTX-M-producing strains showed unique PFGE profiles (<70% similarity) and were unlikely to be derived from a single clone of E. coli (Fig. 2A). However, the strains carrying blaCMY-2 and/or blaDHA-1 genes were genetically more homogenous and demonstrated at least three arbitrary clusters (clusters I, II, and III) of PFGE profiles (Fig. 2B). No or only a few banding patterns were obtained for four CMY-2-producing E. coli strains because their genomic DNAs were constantly autodigested during agarose plug preparation. Thus, a cluster formed by these strains is ignored throughout this paper.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of ESBL- and AmpC β-lactamase-producing E. coli strains isolated from intestinal samples from stray dogs in 2006 and 2007 in the Republic of Korea were investigated. This study provides the first extensive molecular report of plasmid-mediated ESBLs or AmpC β-lactamases in E. coli strains isolated from dogs in the Republic of Korea. Among 628 canine E. coli isolates investigated, 12 (1.91%) produced CTX-M-type ESBLs and 22 (3.5%) produced pAmpCs. A similar frequency of CTX-M-type ESBLs but a higher frequency of pAmpCs was observed in E. coli strains isolated from dogs and cats in the United States (26). Likewise, a similar frequency of genes encoding CTX-M or pAmpC was observed among ESC-resistant canine and feline E. coli isolates in Europe (5). In contrast, a high prevalence of blaCTX-M genes was reported for E. coli isolates from companion animals from China (37). Furthermore, in this study, the prevalence and types of CTX-M ESBLs detected were much higher and diverse, respectively, than those for E. coli strains isolated from sick animals in the Republic of Korea in our previous report (20). This may be associated with the increasing amounts of usage of cephalosporins in animals in the Republic of Korea. According to the Republic of Korea Animal Health Products Association, the most common antimicrobial used in animal hospitals in 2005 was cephalexin, a cephalosporin (19).

In this study, the ESBL-producing canine E. coli isolates carried various blaCTX-M genes, and some of them also contained blaTEM-1. Six different CTX-M types were detected. These blaCTX-M variants have been reported previously for E. coli strains isolated from companion animals, such as dogs and cats, from Europe (5), Chile (22), the United States (26), China (37), and Hong Kong SAR (15). In the Republic of Korea, we reported for the first time (in 2009) the presence of blaCTX-M-14 in an E. coli strain isolated in 2004 from a clinically sick dog (20). Similarly, the pAmpC gene encoding CMY-2 detected in this study, alone or in combination with TEM-1, has previously been reported for E. coli strains isolated from dogs from Europe and the United States (5, 26). However, CMY-2 has not been reported previously in dogs from the Republic of Korea. Furthermore, the blaDHA-1 gene, which was identified in two isolates in this study and whose occurrence has previously been described for human clinical E. coli isolates from the Republic of Korea (39), has never been reported for E. coli strains from companion animals across the globe. Thus, to our knowledge, this study represents the first report of blaDHA-1 in E. coli strains from dogs. Overall, our findings indicate the increasing diversity of ESBL and/or pAmpC genes in E. coli strains isolated from dogs, which constitutes a potential public health concern.

In the present study, for the majority of isolates, the blaCTX-M or blaCMY-2 gene was able to be transferred by conjugation to a recipient E. coli strain. Interestingly, the blaDHA-1 and/or blaTEM-1 gene did not transfer to recipient strains, which indicates that these genetic determinants may be located in a plasmid different from the one which carries the blaCTX-M or blaCMY-2 gene. Furthermore, our results indicate that the horizontal dissemination of blaCTX-M and blaCMY-2 genes in canine E. coli strains is due mainly to IncF and IncI1-Iγ plasmids, respectively, despite the presence of various plasmid backbones as indicated by multiple replicon types in the wild strains. Moreover, the plasmids of one isolate (strain E-127) among the few wild isolates tested for comparison purposes did not hybridize with the blaCTX-M-9 cluster gene probe, despite the presence of a blaCTX-M-9 cluster gene. This strain may have harbored the blaCTX-M gene in a chromosome. Recently, Kim et al. reported the presence of the blaCTX-M-14 gene in the chromosome for eight E. coli isolates and on both the plasmid and chromosome for five isolates from the Republic of Korea (17).

Several previous studies have reported the presence of the ISEcp1 element upstream of blaCTX-M in Enterobacteriaceae (20, 40). The absence of amplification of the ISEcp1--CTX-M-3 region for one strain in the current study might be due to the presence of a truncated ISEcp1 sequence (11). Furthermore, identification of IS903 and IS903 tnpA downstream of blaCTX-M in six and four isolates, respectively, and in their transconjugants, suggests that only four of the studied strains had the transposase gene of this insertion sequence. A similar organization associated with blaCTX-M in Enterobacteriaceae has been well documented in the literature (11). Detection of ISEcp1 upstream of various blaCTX-M genes belonging to the CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-9 families and of all blaCMY-2 genes and on different plasmid backbones indicates that ISEcp1 plays an important role in the capture, expression, and continuous mobilization of blaCTX-M and blaCMY-2 genes.

In this study, 1 and 4 E. coli isolates harboring blaCTX-M genes and 2 and 12 isolates harboring blaCMY-2 genes belonged to virulent phylogenetic groups B2 and D, respectively. These findings have raised concerns regarding the transfer of CTX-M- or CMY-2-producing canine E. coli isolates belonging to virulent phylogroups from dogs to humans, since humans share the same environment and remain in close contact with them. Nevertheless, none of the studied isolates belonged to an internationally disseminated E. coli ST131 clone, in contrast to previous reports (12, 31). Furthermore, molecular typing results showed that CTX-M-producing canine E. coli strains were clonally very diverse, which suggests that mainly horizontal gene transmission may be responsible for the spread of blaCTX-M genes in E. coli strains among dogs, rather than clonal expansion from a single clone of E. coli. In contrast, both clonal and horizontal transmission is responsible for the spread of blaCMY-2 genes in canine E. coli strains in the Republic of Korea.

In general, there was good correlation between phylogenetic groups, STs, and groupings of strains in each cluster by XbaI-PFGE, which in turn corresponded well with the epidemiological data, including geographic origin (Fig. 2B). The major cluster (cluster I) consisted of five strains with indistinguishable PFGE profiles and was followed by a second cluster (cluster II) which consisted of three highly related strains (>97% similarity) and a third cluster (cluster III) which consisted of two strains with identical profiles. The five strains grouped under cluster I were isolated from stray dogs that were cared for in the same stray dog shelter in Seoul, where stray dogs are usually kept for 1 month and then euthanized if no owners claim them during this period. All of these dogs were from Seoul Metropolitan Province, except for one from the adjoining Gyeonggi Province. Interestingly, all of these E. coli isolates corresponded to the ST648 lineage, belonging to virulent phylogroup D. Similarly, the three isolates of cluster II were isolated from stray dogs from the same dog shelter in Seoul and corresponded to ST648 clones belonging to virulent phylogroup D. Overall, 42.9% (9/21 isolates) of CMY-2-positive isolates belonged to the phylogroup D lineage ST648. Importantly, E. coli strains of the group D ST648 clonal lineage have been reported to cause a majority of ESBL-producing E. coli bacteremia cases in the Netherlands (42). A further worrying development is that this ST belonging to phylogroup D has been shown to produce New Delhi metallo (NDM)-type carbapenemases among hospitalized patients in Pakistan and the United Kingdom (16, 23). On the whole, our results demonstrate that the clonal spread of blaCMY-2 was driven mainly by ST648 clones belonging to virulent phylogroup D.

In conclusion, our results highlight the emergence of ESBL- and pAmpC-producing E. coli strains among dogs in the Republic of Korea. The occurrence of blaCTX-M or blaCMY-2/DHA-1 genes in isolates from dogs underlines the possibility of spread of such strains to humans. To our knowledge, this is the first report of blaDHA-1 in E. coli strains isolated from companion animals. This study also represents the first report of CMY-2 β-lactamase-producing E. coli isolates from dogs in the Republic of Korea. Our results suggest the need for better long-term surveillance of ESBLs and/or pAmpCs among companion animal isolates in parallel with human and other animal isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Animal, Plant, and Fisheries Quarantine and Inspection Agency, Ministry of Food, Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Republic of Korea.

We thank Alessandra Carattoli (Istituto Superiore Di Sanita, Rome, Italy) and Rebecca L. Lindsey (USDA-ARS, Russell Research Center, Athens, GA) for kindly providing the plasmid incompatibility group control strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 February 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Batchelor M, Threlfall EJ, Liebana E. 2005. Cephalosporin resistance among animal-associated enterobacteria: a current perspective. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 3:403–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Batchelor M, et al. 2005. blaCTX-M genes in clinical Salmonella isolates recovered from humans in England and Wales from 1992 to 2003. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1319–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bauernfeind A, Chong Y, Schweighart S. 1989. Extended broad spectrum β-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae including resistance to cephamycins. Infection 17:316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Branger C, et al. 2005. Genetic background of Escherichia coli and extended-spectrum β-lactamase type. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:54–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carattoli A, et al. 2005. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Escherichia coli isolated from dogs and cats in Rome, Italy, from 2001 to 2003. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:833–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carattoli A, et al. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J. Microbiol. Methods 63:219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555–4558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 20th informational supplement. M100–S20-U Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corvec S, Caroff N, Espaze E, Marraillac J, Reynaud A. 2002. −11 mutation in the ampC promoter increasing resistance to β-lactams in a clinical Escherichia coli strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3265–3267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Vincent SJ, Reid-Smith R. 2006. Stakeholder position paper: companion animal veterinarian. Prev. Vet. Med. 73:181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eckert C, Gautier V, Arlet G. 2006. DNA sequence analysis of the genetic environment of various blaCTX-M genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:14–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ewers C, et al. 2010. Emergence of human pandemic O25:H4-ST131 CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli among companion animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gautom RK. 1997. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other gram-negative organisms in 1 day. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2977–2980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guardabassi L, Schwarz S, Lloyd DH. 2004. Pet animals as reservoirs of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ho PL, et al. 2011. Extensive dissemination of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli with multidrug resistance to ‘critically important’ antibiotics among food animals in Hong Kong, 2008–10. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:765–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hornsey M, Phee L, Wareham DW. 2011. A novel variant (NDM-5) of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli ST648 isolate recovered from a patient in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5952–5954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim J, et al. 2011. Characterization of IncF plasmids carrying the blaCTX-M-14 gene in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Korea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1263–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim J, Lim Y-M, Jeong Y-S, Seol S-Y. 2005. Occurrence of CTX-M-3, CTX-M-15, CTX-M-14, and CTX-M-9 extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates in Korea. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1572–1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Korea Animal Health Products Association 2005. Annual survey of antimicrobial usage in animals in Korea. http://kahpa.or.kr Accessed 21 September 2009

- 20. Lim SK, Lee HS, Nam HM, Jung SC, Bae YC. 2009. CTX-M-type beta-lactamase in Escherichia coli isolated from sick animals in Korea. Microb. Drug Resist. 15:139–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matsumoto Y, Ikeda F, Kamimura T, Yokota Y, Mine Y. 1988. Novel plasmid-mediated beta-lactamase from Escherichia coli that inactivates oxyimino-cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1243–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moreno A, Bello H, Guggiana D, Domínguez M, González G. 2008. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases belonging to CTX-M group produced by Escherichia coli strains isolated from companion animals treated with enrofloxacin. Vet. Microbiol. 129:203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mushtaq S, et al. 2011. Phylogenetic diversity of Escherichia coli strains producing NDM-type carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2002–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nam HM, et al. 2010. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in fecal Escherichia coli isolates from stray pet dogs and hospitalized pet dogs in Korea. Microb. Drug Resist. 16:75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, et al. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Keefe A, Hutton TA, Schifferli DM, Rankin SC. 2010. First detection of CTX-M and SHV extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Escherichia coli urinary tract isolates from dogs and cats in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3489–3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pedersen K, et al. 2007. Occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from diagnostic samples from dogs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:775–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perez-Perez FJ, Hanson ND. 2002. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2153–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pfeifer Y, Cullik A, Witte W. 2010. Resistance to cephalosporins and carbapenems in Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300:371–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Philippon A, Arlet G, Jacoby GA. 2002. Plasmid-determined AmpC-type β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pomba C, da Fonseca JD, Baptista BC, Correia JD, Martinez-Martinez L. 2009. Detection of the pandemic O25-ST131 human virulent Escherichia coli CTX-M-15-producing clone harboring the qnrB2 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes in a dog. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:327–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rayamajhi N, et al. 2008. Characterization of TEM-, SHV- and AmpC-type beta-lactamases from cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from swine. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 124:183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rossolini GM, D'Andrea MM, Mugnaioli C. 2008. The spread of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl 1):33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saladin M, et al. 2002. Diversity of CTX-M beta-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sidjabat HE, et al. 2007. Identification of plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum and AmpC beta-lactamases in Enterobacter spp. isolated from dogs. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simjee S, et al. 2002. Characterization of Tn1546 in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolated from canine urinary tract infections: evidence of gene exchange between human and animal enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4659–4665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun Y, et al. 2010. High prevalence of blaCTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes in Escherichia coli isolates from pets and emergence of CTX-M-64 in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1475–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tamang MD, et al. 2007. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi associated with a class 1 integron carrying the dfrA7 gene cassette in Nepal. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:330–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tamang MD, et al. 2008. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS among clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in a Korean hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4159–4162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tamang MD, et al. 2011. Emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14)-producing nontyphoid Salmonella with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin among food animals and humans in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2671–2675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tartof SY, Solberg OD, Manges AR, Riley LW. 2005. Analysis of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli clonal group by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5860–5864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. van der Bij AK, et al. 2011. Clinical and molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli causing bacteremia in the Rotterdam Area, Netherlands. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3576–3578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yoo JS, et al. 2010. High prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from long-term care facilities in Korea. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 67:261–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]