Abstract

Epidemiological cutoff values (ECV) are commonly used to separate wild-type isolates from isolates with reduced susceptibility to antifungal drugs, thus setting the foundation for establishing clinical breakpoints for Aspergillus fumigatus. However, ECVs are usually determined by eye, a method which lacks objectivity, sensitivity, and statistical robustness and may be difficult, in particular, for extended and complex MIC distributions. We therefore describe and evaluate a statistical method of MIC distribution analysis for posaconazole, itraconazole, and voriconazole for 296 A. fumigatus isolates utilizing nonlinear regression analysis, the normal plot technique, and recursive partitioning analysis incorporating cyp51A sequence data. MICs were determined by using the CLSI M38–A2 protocol (CLSI, CLSI document M38–A2, 2008) after incubation of the isolates for 48 h and were transformed into log2 MICs. We found a wide distribution of MICs of all azoles, some ranging from 0.02 to 128 mg/liter, with median MICs of 32 mg/liter for itraconazole, 4 mg/liter for voriconazole, and 0.5 mg/liter for posaconazole. Of the isolates, 65% (192 of 296) had mutations in the cyp51A gene, and the majority of the mutants (90%) harbored tandem repeats in the promoter region combined with mutations in the cyp51A coding region. MIC distributions deviated significantly from normal distribution (D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test P value, <0.001), and they were better described with a model of the sum of two Gaussian distributions (R2, 0.91 to 0.96). The normal plot technique revealed a mixture of two populations of MICs separated by MICs of 1 mg/liter for itraconazole, 1 mg/liter for voriconazole, and 0.125 mg/liter for posaconazole. Recursive partitioning analysis confirmed these ECVs, since the proportions of isolates harboring cyp51A mutations associated with azole resistance were less than 20%, 20 to 30%, and >70% when the MICs were lower than, equal to, and higher than the above-mentioned ECVs, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Given the limited clinical data and the problems of establishing an in vitro-in vivo clinical correlation for Aspergillus fumigatus infections (32, 33), the distributions of MICs are often analyzed to distinguish wild-type populations from those with (acquired) resistance mechanisms and to set epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs) (26). Although the correlation of these analyses with clinical outcomes is uncertain, ECVs will describe the wild-type population and help to detect isolates with reduced susceptibility (29).

Few published studies describe the determination of ECVs for Aspergillus species, for which the ECV is established by visual observation of MIC distribution without any rigorous statistical evaluation, rendering the possibility of bias in the analysis (9, 10, 25, 26). A more robust statistical technique based on deviation from Gaussian distribution has been applied to determine ECVs for nine antifungal drugs for Scedosporium species (19). The advantages of this technique are its objectiveness, statistical robustness, and sensitivity in detecting departure from normal distribution and in detecting mixture of MIC subpopulations.

Analysis of isolates with known molecular mechanisms associated with antifungal resistance can confirm ECVs determined from the analysis of MIC distributions. Azole resistance in A. fumigatus has been associated with numerous mutations in the cyp51A gene, including the tandem repeat in the promoter region and changes causing amino acid substitutions (15, 27, 28). To date, the lack of resistant populations has been an obstacle in establishing breakpoints for A. fumigatus. This is the first study that incorporates a significant collection of A. fumigatus isolates with a non-wild-type azole resistance phenotype.

In the present study, we analyzed the MIC distributions for three azoles used in the treatment of aspergillosis, voriconazole, posaconazole, and itraconazole, for 296 A. fumigatus clinical isolates. MIC distributions were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis based on the model of the sum of two Gaussian distributions, the normal plot technique, and recursive partitioning analysis incorporating data on cyp51A mutations associated with azole resistance to determine ECVs for each azole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

The fungus culture collection of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, was searched for A. fumigatus isolates which had undergone sequence-based analysis of the cyp51A gene. This selection criterion resulted in 296 isolates, of which 104 had no Cyp mutations and 197 had at least one mutation. The Cyp51A genotypes were used to define the wild-type and non-wild-type isolates. The isolates recovered between 1994 and 2010 from various clinical specimens (bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, sputum, pus, and ear and throat swabs) were stored in 10% glycerol at −80°C. Isolates were revived by being subcultured twice onto Sabouraud dextrose agar with chloramphenicol at 30°C. Inoculum suspensions were prepared from 5- to 7-day-old cultures in saline and adjusted spectrophotometrically to 80 to 82% transmittance to twice the final inoculum, which ranged from 0.5 × 104 to 4.5 × 104 CFU/ml.

Molecular analysis.

The morphological identification of the A. fumigatus isolates was confirmed by sequencing of the β-tubulin and calmodulin genes, as described previously (28). Genetic relationships of all isolates were determined by microsatellite genotyping (8). The cyp51A coding region and its promoter were sequenced as described previously (20, 21). Cyp51A genotypes were used to define non-wild-type isolates.

Antifungal drugs.

Pure powders of posaconazole (Schering-Plough B.V., Boxmeer, the Netherlands), itraconazole (Janssen-Cilag, Tilburg, the Netherlands), and voriconazole (Pfizer, Capelle aan den IJssel, the Netherlands) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to prepare stock solutions of 5,000 mg/ml. Twofold serial drug dilutions were prepared in RPMI 1640-MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) to twice the final concentration, which ranged from 0.015 to 128 mg/liter.

Susceptibility testing.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed according to the CLSI M38–A2 protocol (5). Briefly, 100-μl culture preparations were inoculated into flat-bottom wells of 96-well microtiter plates containing 100-μl drug dilutions. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The MICs of all drugs were determined visually as the lowest concentrations with no visible growth. MIC testing was performed on the day of isolation. Data were retrieved from a database and analyzed retrospectively.

Analysis. (i) Descriptive statistics.

The median MIC and the range of MICs of each drug were determined. The high off-scale MICs were included in the analysis by converting the MICs to the next higher drug concentrations. Low off-scale MICs were left unchanged. To analyze the MIC distributions, MICs were transformed into log2 values. The skewness and kurtosis of each MIC distribution were determined. Skewness quantifies the degree of symmetry of the distribution, whereas kurtosis quantifies the extent to which the shape of the data distribution matches the normal distribution. A symmetrical, normal distribution has a skewness and a kurtosis of 0.

(ii) Deviation from normal distribution.

Deviations from the normal distribution were analyzed by the D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus K2 normality test, where K2 is a value incorporating both skewness and kurtosis, using Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA) after log transformation. The software first computed the skewness and kurtosis to quantify how far from normal the distribution was in terms of asymmetry and shape. It then calculated how much each of these values differed from the value expected with a normal distribution and computed a single P value from the sum of these discrepancies. P values smaller than 0.05 indicated a statistically significant deviation.

To further analyze the deviation from normality, the normal plot technique was used and the presence of more than one MIC distribution in the data was explored. The normal plot is constructed by sorting the MICs into ascending order and then plotting the data against the corresponding normal scores (1). The normal score is the number of standard deviations below or above the mean and is calculated based on Blom's proportional estimation formula, Pi = 100 × (i − 3/8)/(n + 1/4), in which Pi is the quantile from the standard normal distribution, i is the rank for that observation, and n is the sample size. A straight line in the normal plot represented one population of data. Thus, different lines in these plots indicated different MIC populations with different standard deviations. In order to determine statistically the different lines in a normal plot, normal scores lower and higher than a MIC were analyzed by linear regression analysis and the slopes and intercepts between the two normal score data sets were compared by analysis of variance to calculate the F statistic using Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). The ECV was determined as the lowest MIC that best separated the normal scores, i.e., with the largest F statistic.

(iii) Nonlinear regression analysis.

To confirm the presence of more than one MIC distribution, frequency distributions of MIC data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis based on the following Gaussian equation: y = amplitude × e−0.5 × [(x − mean)/SD]2, in which the amplitude is the height of the center of the MIC distribution, the mean is the MIC value at the center of the distribution, and SD is a measure of the width of the MIC distribution (calculations were performed using Prism 5.0 software). Data were also analyzed with a model of a sum of two Gaussian distributions. The two fits were compared with the extra sum of squares F test, for which the null hypothesis was the Gaussian distribution and the alternative hypothesis was the sum of two Gaussian distributions. The F(p2-p1, n-p2) statistic has p2-p1, n-p2 degrees of freedom where p1 and p2 are the numbers of parameters of model 1 and model 2, respectively, and n is the number of points analyzed. A P value of less than 0.05 indicated rejection of the null hypothesis and acceptance of the alternative hypothesis.

(iv) Recursive partitioning analysis.

To confirm the MIC cutoffs determined by the normal plot technique, MIC data and cyp51A mutations were analyzed by recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) using JMP5.0.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). RPA does not make any implicit assumption about the underlying distributions of MICs and the association between MICs and cyp51A mutations.

RPA partitions MIC data according to a relationship between the MICs and cyp51A mutations, creating a tree of partitions. The split is chosen to maximize the difference in the responses between the two branches of the split. These splits (or partitions) of the data are done recursively, forming a tree of decision rules until the desired fit, if any, is reached. The estimated probability of the presence or absence of cyp51A mutations (response) becomes the fitted value, and the most significant split is determined by the largest likelihood ratio chi-square statistic. The sorting efficiency of RPA was assessed by using the area under the receiver-operator curve (AUROC). Cross validation was achieved by using 5-fold cross validation, which randomly assigned all the (nonexcluded) rows to one of the five groups and then calculated the error for each point by using means or rates estimated from all of the groups, except the group to which the point belonged. The result is a cross-validated R2 value. Finally, the Fisher exact test was performed in order to compare the actual data to the predicted data based on the MIC cutoffs determined by the RPA with respect to the presence of cyp51A mutations.

RESULTS

The MIC distribution for each antifungal drug is shown in Table 1. Wide distributions of MICs, some ranging from as low as 0.02 mg/liter to >64 mg/liter, were found for all azoles. The median MICs were 32 mg/liter for itraconazole, 4 mg/liter for voriconazole, and 0.5 mg/liter for posaconazole. The wide MIC distributions increased the probability of detecting all existing MIC subpopulations and reduced the bias in determining MIC cutoffs from a narrower MIC distribution.

Table 1.

MICs of itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole for 296 A. fumigatus clinical isolatesa

| Parameter | No. of isolates (no. with cyp51A mutations), value, or status for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Itraconazole | Voriconazole | Posaconazole | |

| MICs (mg/liter) | |||

| ≤0.03 | 1 (0) | 0 | 37 (2) |

| 0.06 | 2 (0) | 0 | 36 (4) |

| 0.13 | 43 (1) | 0 | 15 (3) |

| 0.25 | 34 (3) | 27 (4) | 59 (49) |

| 0.5 | 9 (2) | 44 (3) | 111 (102) |

| 1 | 3 (1) | 30 (9) | 28 (25) |

| 2 | 0 | 41 (32) | 3 (2) |

| 4 | 2 (2) | 68 (61) | 0 |

| 8 | 6 (4) | 54 (52) | 0 |

| 16 | 19 (16) | 28 (28) | 0 |

| 32 | 176 (162) | 4 (3) | 7 (6) |

| ≥64 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Characteristics of MIC data | |||

| Median | 32.0 | 4.0 | 0.5 |

| Mode | 32.0 | 4.0 | 0.5 |

| Minimum | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.02 |

| Maximum | 128.0 | 32.0 | 32.0 |

| Skewness | −0.8339 | −0.2133 | 0.3632 |

| Kurtosis | −1.177 | −0.9978 | 2.121 |

| D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test results | |||

| K2 | 166.0 | 57.23 | 24.10 |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Passed | No | No | No |

Numbers in parentheses represent isolates with Cyp51 mutations. Descriptive characteristics (median, range, skewness, and kurtosis) of the MIC distributions for three azoles after log transformation, together with the results of the D'Agostino-Pearson normality test, are presented.

cyp51A genotype.

Of all isolates, 65% (192 of 296) had mutations in the cyp51A gene known to be associated with azole resistance (4, 15, 28, 31). Among those with cyp51A mutations, 174 (90%) had the 34-bp tandem repeat (TR) unit in the promoter region linked with the amino acid substitution L98H and the remaining 18 isolates (10%) had the following amino acid mutations: G138C (2 isolates), G54W (2 isolates), G54E (3 isolates), M220I/V/K (4 isolates), F219I (5 isolates), and P216L (2 isolates).

MIC distributions.

The MIC distributions for all three azoles were statistically significantly deviated from normal distribution, as shown in Table 1. The skewness was positive (the right tail was heavier than the left tail) for the posaconazole MIC distribution and negative for the itraconazole and voriconazole MIC distributions (Fig. 1A). The kurtosis was negative (indicating flatter distribution) for the itraconazole and voriconazole MIC distributions and positive (indicating peaked distribution) for the posaconazole MIC distribution. The largest deviation from normal distribution was observed for itraconazole (K2, 166), followed by voriconazole (K2, 57.23) and posaconazole (K2, 24.10). None of the MIC distributions passed the normality test (P < 0.0001), confirming the significant deviation from normal distribution.

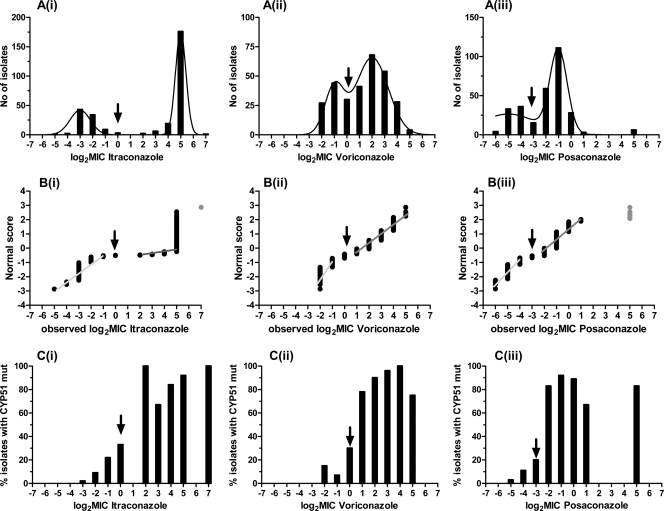

Fig 1.

Distributions of 296 MICs (A), normal score plots (B), and percentages of isolates harboring cyp51A mutations (C) for itraconazole (i), voriconazole (ii), and posaconazole (iii). Arrows indicate ECVs that separate low and high MIC groups. Gray dots were not included in the analysis because they were off scale.

This deviation was also confirmed by the normal plot technique, in which data points had two lines, indicating the presence of two populations of MICs (Fig. 1B). As shown by the nonlinear regression, these two subpopulations followed the Gaussian distribution. Nonlinear regression analysis showed that the preferred model to describe the MIC distributions for itraconazole (F2,11 = 17.39 [where 2 and 11 are degrees of freedom of the F statistic]; P = 0.0004), voriconazole (F2,11 = 32.10; P = 0.0001), and posaconazole (F2,11 = 13.80; P = 0.0034) was the sum of two Gaussian distributions (R2, 0.91 to 0.96) (Fig. 1A). Because posaconazole MIC distribution may be trimodal, a model of the sum of three Gaussian distributions was fitted to the data and compared with the model of the sum of two Gaussian distributions. The preferred model was the sum of two Gaussian distributions, mainly because the fit of the model of the sum of three Gaussian distributions was ambiguous. More data around the third MIC subpopulation will be needed in order to confirm the trimodal distribution of posaconazole MICs.

Determination of ECV.

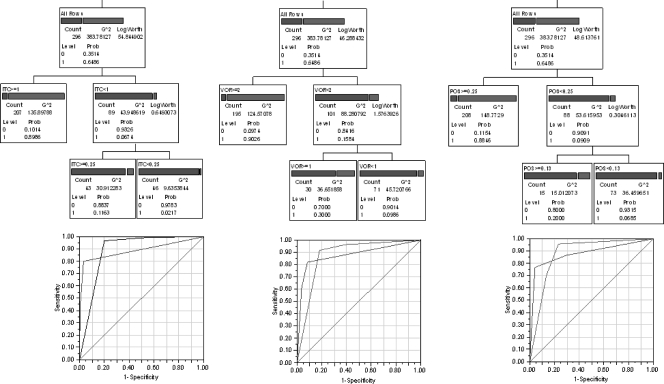

ECVs that split the MIC distribution could be determined statistically with the F statistic, as indicated by the arrows in the normal plots shown in Fig. 1B. The lowest ECV with the largest F statistic was observed at 1 mg/liter for itraconazole (F2,288 = 24.65), 1 mg/liter for voriconazole (F2,262 = 42.89), and 0.125 mg/liter for posaconazole (F2,270 = 69.12). These ECVs were confirmed by analysis of the presence of cyp51A mutations associated with azole resistance, since the proportions of isolates harboring these mutations were less than 20%, 20 to 30%, and >70% when the MICs were lower than, equal to, and higher than the above-mentioned ECVs, respectively. These cutoffs were also found by the RPA, as shown in Fig. 2. The AUROCs were 0.87 to 0.88 and the fivefold cross validation R2 values were 0.46 to 0.54 for all three drugs. The Fisher exact test showed statistically significant association between the actual status and the predicted status of cyp51A mutation based on the RPA ECVs (89% agreement, χ2 = 181.4, and P < 0.0001 for posaconazole; 88% agreement, χ2 = 170.9, and P < 0.0001 for voriconazole; and 90% agreement, χ2 = 203.9, and P < 0.0001 for itraconazole).

Fig 2.

Recursive partitioning analysis of MICs and cyp51A mutations. The partition trees for MICs of itraconazole (ITC; left), voriconazole (VOR; middle), and posaconazole (POS; right) based on the presence (1; right bar) or absence (0; left bar) of cyp51A mutations are shown. The AUROCs were 0.87 to 0.88 and the 5-fold cross validation R2 values were 0.46 to 0.54 for all three drugs. G2, likelihood ratio chi-square; prob, probability.

DISCUSSION

In the absence of valid susceptibility breakpoints for Aspergillus spp., ECVs derived from the analysis of MIC distribution are used to distinguish wild-type susceptible isolates from non-wild-type resistant isolates. To date, the criteria used to establish ECVs for filamentous fungi are based on arbitrary statistical calculations. Accordingly, previously reported ECVs for A. fumigatus have been based on the frequency distribution of MICs for large collections of clinical isolates. By this approach, the wild-type population was defined as the population within an area around the modal MIC ± 1 2-fold dilution that encompasses >95% of the strains. Populations outside this region were considered to be potentially resistant isolates. In the present study, we set no predefined criteria for separating the isolates with non-wild-type susceptibility from those within the wild-type population and used an unconstrained mathematical model to detect MIC subpopulations corroborated by genotype data associated with azole resistance. Because the MIC distributions for wild-type isolates have been described as unimodal in most of the previous studies, in the present study we included a large collection of non-wild-type isolates in order to better evaluate the subpopulation within this group of isolates. The analysis described here allows reliable ECV determination from any collection of isolates as long as all subpopulations are present.

The ECV of 1 mg/liter for voriconazole and itraconazole is in agreement with a previously determined ECV. However, the ECVs for posaconazole are lower than those determined previously, which were 0.25 and 0.5 mg/liter (9, 25, 26). These ECVs were determined by the eyeball technique based on the modal MIC ± 1 2-fold dilution that encompassed any subset of >95% of the isolates in different studies. The modal MIC is strongly dependent on the collection of isolates (wild type versus non-wild type) and the shape of the MIC distribution (bimodal, skewed distribution). For example, by using the modal MIC ± 1 2-fold dilution for the itraconazole MIC distribution in the present study, the wild-type population would be defined as isolates for which the MIC was 16 to 64 mg/liter, and this would not encompass 95% of the isolates. The bimodal distribution might be the reason why Espinel-Ingroff et al. (9) excluded the upper parts of the posaconazole MIC distribution for the modeled population. Different inclusion criteria for defining the wild-type population may result in different ECVs, as in the case of posaconazole, for which an ECV of 0.25 mg/liter was determined based on a 95% inclusion criterion and an ECV of 0.5 mg/liter was determined based on a 99% inclusion criterion (9, 25, 26). In addition, in most of these studies, the MICs did not span as wide a range as those in our study to allow the subpopulations of MICs to be more easily distinguished. Finally, our study included a large number of isolates with known cyp51A mutations associated with azole resistance, which were used to confirm and validate our methodology, in contrast to previous studies in which no validation methodology was used.

In agreement with the ECV for posaconazole found in the present study, a clinical breakpoint of <0.125 mg/liter for posaconazole was proposed previously when the in vivo exposure-MIC relationship obtained from an experimental murine model of disseminated aspergillosis was bridged with human posaconazole exposure (18). Based on the relationship between the area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h for the free fraction of the drug (fAUC0-24) divided by the MIC (the fAUC0-24/MIC ratio) and survival, near-maximal activity was associated with an fAUC0-24/MIC ratio of 6.6 ± 1.3, a target that can be obtained with standard dosing of posaconazole for A. fumigatus isolates for which MICs are ≤0.0625 mg/liter, while isolates for which MICs are 0.125 mg/liter are associated with an intermediate response. This cutoff was also found in an experimental model of disseminated aspergillosis caused by A. fumigatus isolates for which MICs were 0.031 and 0.5 mg/liter, in which treatment with 1 and 4 mg of posaconazole/kg of body weight, which resulted in drug exposures like that in humans, demonstrated 80 and <40% efficacy, respectively (17). Isolates for which the MIC is 0.25 mg/liter have also been associated with treatment failure in an immunocompromised murine model of aspergillosis (2). Clinical failure was observed for an A. fumigatus isolate for which the MIC was 0.5 mg/liter in a kidney transplant recipient with posaconazole blood levels of 0.6 mg/liter (16). In a recently reported retrospective study with patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, one patient received a standard dose of posaconazole (as salvage therapy) for 45 weeks and the posaconazole MIC increased from 0.125 to 8 mg/liter, which was associated with clinical and radiological deterioration (14). Finally, in another study in which the frequency of azole-resistant isolates was analyzed retrospectively, MICs of posaconazole for all 45 azole-resistant isolates harboring an amino acid substitution encoded in the cyp51A gene were >0.125 mg/liter (15). EUCAST recently proposed a clinical breakpoint of ≤0.125 mg/liter to define susceptibility (12, 13). Thus, a MIC of 0.125 mg/liter may distinguish between susceptible and resistant isolates.

With respect to the ECV for voriconazole of 1 mg/liter found in the present study, an experimental murine model of disseminated aspergillosis demonstrated that voriconazole treatment resulted in high survival rates for A. fumigatus isolates for which MICs were 0.125 and 0.25 mg/liter but not for isolates for which the MIC was 2 mg/liter (17). Voriconazole prevented mortality in an experimental model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with an A. fumigatus isolate for which the MIC was 0.25 mg/liter (22). In a study in which the frequency of azole-resistant isolates was analyzed retrospectively, MICs of voriconazole for 87% of azole-resistant isolates (39 of 45) harboring amino acid substitutions encoded in the cyp51A gene were ≥1 mg/liter (15). Finally, clinical studies with patients with invasive aspergillosis have shown that lack of response to voriconazole therapy is more frequent in patients with voriconazole plasma levels of ≤1 mg/liter (24). Thus, a susceptibility breakpoint of 1 mg/liter could be determined.

For itraconazole, the ECV of 1 mg/liter found in the present study is in agreement with previously determined ECVs (9, 25, 26). In vivo studies of experimental aspergillosis have shown that isolates for which MICs were ≤1 mg/liter were successfully treated with itraconazole and that isolates for which MICs were higher were not (6, 7). In a study in which the frequency of azole-resistant isolates was analyzed retrospectively, all isolates for which MICs were high (>1 mg/liter) had amino acid substitutions encoded in the cyp51A gene (15). Although cyp51A mutations may be the most common azole resistance mechanism, other mechanisms may also be associated with resistance to azoles (3, 23). This explains why some isolates for which MICs were high did not have mutations in the cyp51A gene in the present study. Our analysis supports the clinical breakpoint of ≤1 mg/liter proposed recently by EUCAST (11, 12).

In conclusion, MIC distribution analysis may reveal important information about ECVs and set the foundation for determination of clinical breakpoints by incorporating molecular data on resistance mechanisms, in vivo results from experimental models, and clinical outcome. MIC distribution analysis may be a challenge, particularly for complex and nonuniform distributions. The statistical methods described in the present study can help in analyzing MIC distributions and detecting subpopulations of MICs that correspond to wild-type and resistant isolates. The ECVs of 1, 1, and 0.125 mg/liter determined for itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole were corroborated by resistance mechanisms (Table 2). The ECV in fact corresponded to the upper bound of the MIC distribution for the wild-type susceptible isolates. An intermediate category was included in order to account for a higher percentage of isolates with cyp51A mutations in this group than in the group of isolates for which MICs were lower than the ECVs, which may represent a susceptible population. The group of isolates for which MICs were higher than the ECVs is clearly characterized by a much higher percentage of isolates harboring cyp51A mutations, probably reflecting a resistant population. More in vivo and clinical data for A. fumigatus isolates in each susceptibility group are required in order to confirm these cutoffs as susceptibility breakpoints. The ECVs proposed in the present study may be used to distinguish azole-susceptible from azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates and promote further research for establishing susceptibility breakpoints.

Table 2.

Epidemiological cutoff values and proposed clinical breakpointsa for itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole against A. fumigatus

| Antifungal drug | ECV | Value for classification as: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | ||

| Itraconazole | 1 | ≤0.5 | 1 | ≥2 |

| Voriconazole | 1 | ≤0.5 | 1 | ≥2 |

| Posaconazole | 0.125 | ≤0.0625 | 0.125 | ≥0.25 |

Values are in milligrams per liter.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 February 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Altman DG. 1999. Practical statistics for medical research, p 132–143 Chapman & Hall, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arendrup MC, et al. 2010. Development of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy associated with change in virulence. PLoS One 5:e10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bueid A, et al. 2010. Azole antifungal resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: 2008 and 2009. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2116–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Camps SMT, et al. 2012. Rapid induction of multiple resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy: a case study and review of the literature. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:10–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. CLSI 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi; approved standard—second edition. CLSI document M38–A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dannaoui E, et al. 2001. Acquired itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Denning DW, et al. 1997. Correlation between in-vitro susceptibility testing to itraconazole and in-vivo outcome of Aspergillus fumigatus infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:401–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Valk HA, et al. 2005. Use of a novel panel of nine short tandem repeats for exact and high-resolution fingerprinting of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4112–4120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Espinel-Ingroff A, et al. 2010. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the triazoles and six Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38–A2 document). J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:3251–3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Espinel-Ingroff A, et al. 2011. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for caspofungin and Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38–A2 document). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2855–2859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. EUCAST 2011. Itraconazole and Aspergillus spp. Rationale for the EUCAST clinical breakpoints, version 1.0. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Rationale_documents/Itraconazole_Aspergillus_v1_0f.pdf

- 12. EUCAST 2008. EUCAST technical note on the method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for conidia-forming moulds. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:982–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. EUCAST 2011. Posaconazole and Aspergillus spp. Rationale for the EUCAST clinical breakpoints, version 1.0. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Rationale_documents/Posaconazole_Aspergillus_rationale_1_0f.pdf

- 14. Felton TW, et al. 2010. Efficacy and safety of posaconazole for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51:1383–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Howard SJ, et al. 2009. Frequency and evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with treatment failure. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1068–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuipers S, et al. 2011. Failure of posaconazole therapy in a renal transplant patient with invasive aspergillosis due to Aspergillus fumigatus with attenuated susceptibility to posaconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3564–3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mavridou E, Bruggemann RJ, Melchers WJ, Mouton JW, Verweij PE. 2010. Efficacy of posaconazole against three clinical Aspergillus fumigatus isolates with mutations in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:860–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mavridou E, Meletiadis J, Bruggemann RJ, Verweij P, Mouton JW.Abstr. 50th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother; 2010. http://www.icaac.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meletiadis J, et al. 2002. In vitro activities of new and conventional antifungal agents against clinical Scedosporium isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:62–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mellado E, Diaz-Guerra TM, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2001. Identification of two different 14-alpha sterol demethylase-related genes (cyp51A and cyp51B) in Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2431–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mellado E, et al. 2007. A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of cyp51A alterations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1897–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murphy M, Bernard EM, Ishimaru T, Armstrong D. 1997. Activity of voriconazole (UK-109,496) against clinical isolates of Aspergillus species and its effectiveness in an experimental model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:696–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nascimento AM, et al. 2003. Multiple resistance mechanisms among Aspergillus fumigatus mutants with high-level resistance to itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1719–1726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pascual A, et al. 2008. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with invasive mycoses improves efficacy and safety outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pfaller MA, et al. 2009. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3142–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rodriguez-Tudela JL, et al. 2008. Epidemiological cutoffs and cross-resistance to azole drugs in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2468–2472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Snelders E, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2011. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a new challenge in the management of invasive aspergillosis? Future Microbiol. 6:335–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Snelders E, et al. 2008. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 5:e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turnidge J, Kahlmeter G, Kronvall G. 2006. Statistical characterisation of bacterial wild-type MIC value distributions and the determination of epidemiological cut-off values. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12:418–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reference deleted.

- 31. van der Linden JW, et al. 2011. Clinical implications of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands, 2007–2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:1846–1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verweij PE, Howard SJ, Melchers WJ, Denning DW. 2009. Azole-resistance in Aspergillus: proposed nomenclature and breakpoints. Drug Resist. Updat. 12:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Verweij PE, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2007. Multiple-triazole-resistant aspergillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:1481–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]