Abstract

Nanoenabled drug delivery systems against tuberculosis (TB) are thought to control pathogen replication by targeting antibiotics to infected tissues and phagocytes. However, whether nanoparticle (NP)-based carriers directly interact with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and how such drug delivery systems induce intracellular bacterial killing by macrophages is not defined. In the present study, we demonstrated that a highly hydrophobic citral-derived isoniazid analogue, termed JVA, significantly increases nanoencapsulation and inhibits M. tuberculosis growth by enhancing intracellular drug bioavailability. Importantly, confocal and atomic force microscopy analyses revealed that JVA-NPs associate with both intracellular M. tuberculosis and cell-free bacteria, indicating that NPs directly interact with the bacterium. Taken together, these data reveal a nanotechnology-based strategy that promotes antibiotic targeting into replicating extra- and intracellular mycobacteria, which could actively enhance chemotherapy during active TB.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a major human pathogen which infects one-third of the world's population and causes tuberculosis (TB) in 9.4 million people each year (13, 49). Multidrug chemotherapy has been used for more than 50 years, and isoniazid (INH) has been shown to be one of the most effective antimycobacterial compounds (31, 39). Although such effective drugs are available throughout the world, several factors, including drug toxicity and poor patient compliance, may contribute to the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains (18, 24). In 2008, MDR-TB caused an estimated 150,000 deaths (16, 50), which seriously affects public health worldwide, indicating that while an effective TB vaccine has not been discovered, strategies such as the development of novel drugs (5, 40), the modification of old drugs (24), and the generation of new delivery systems (37, 45) are needed.

More recently, nanotechnology-based strategies have been employed in an attempt to increase drug cell targeting, thus reducing chemotherapy-associated side effects and enhancing the containment of infection (28, 29). In the case of TB, nanoenabled drug delivery systems are thought to reach mycobacteria within granulomas during active disease and decrease time as well as dose compared to the currently used multidrug toxic combination (18, 37). Different nanocarriers have been developed for the delivery of several antimycobacterial antibiotics (7, 45), and poly-lactide-coglycolic acid (PLGA)-based particles encapsulated with INH are among the most studied (37). For example, compared to soluble INH exposure, it has been demonstrated that M. tuberculosis-infected animals treated with biodegradable polymeric drug carriers display decreased bacterial growth in tissues (12, 36). In addition, when INH was associated with nanoparticles (NPs), a lower dose of INH appeared to be sufficient to enhance M. tuberculosis killing (43). These pieces of evidence suggest that drug NPs promote enhanced mycobacterial killing in a lower-dose system, which would decrease side effects, improve patient compliance, and thus affect the development of drug resistance (7, 18, 37, 45). Although it has been thought that nanoenabled systems should be tested against active TB, there remains a paucity of information on how antibiotic NPs interact with M. tuberculosis at the cellular level.

M. tuberculosis infection begins with bacterial uptake by phagocytes, such as macrophages at the primary site of exposure (9, 46). Following infection, a complex myriad of cellular interactions leads to granuloma formation, which is critical to contain mycobacterial proliferation (11, 14). However, factors such as HIV coinfection, undernourishment, and primary immune deficiencies establish an environment that may enhance bacterial growth, leading to active disease and bacterial dissemination (10, 41, 42). During active TB, for example, high numbers of M. tuberculosis are found in necrotic granulomas (19, 21, 34), which may be difficult areas to be appropriately reached by drugs during chemotherapy (34, 46). Taken together, these observations point out that anti-TB nanoenabled systems should be designed to target antibiotics into mycobacteria, which may be found in the extracellular milieu and/or in intracellular compartments (19, 46). In addition, chemical modifications of currently used drugs can be performed to enhance drug-NP interactions with M. tuberculosis and macrophages harboring bacteria. However, whether antibiotic NP directly interacts with M. tuberculosis outside and inside macrophages has not been formally demonstrated.

In the present study, we have developed a novel antimycobacterial drug-NP carrier which displays high activity against extracellular and intracellular mycobacteria. In addition, the observed anti-TB effects were associated with increased cellular interactions of NPs and bacteria, probably by enhancing intracellular bioavailability of a citral-derived INH analogue. These findings provide evidence that nanoenabled carriers are generated to target both extra- and intracellular mycobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

JVA, synthesis, and log P measurements.

Isoniazid (Sigma-Aldrich) (3.5 g; 25.6 mmol) was added to a solution of citral (a commercial mixture of geranial and neral; 3.0 g; 19.7 mmol) diluted in 50 ml of anhydrous methanol (MeOH). The reaction mixture was stirred at 60°C for 24 h, followed by concentration under reduced pressure and the addition of ethyl ether (25 ml). After 48 h at room temperature, the solid formed was isolated by filtration and dried to yield the compound E-N2-3,7-dimethyl-2-E,6-octadienylidenyl isonicotinic acid hydrazide (JVA) (3.2 g, 60% yield). Melting point, 126 to 128°C. IR (KBr): 3,044 (C-Harom.), 2,982 (C-Haliphatic), 1,700 (C=O). 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ, 1.5 to 1.7 (3s, 9H, CH3), 2.1 (s, 4H, H5), 5.0 (s, 1H, H6), 5.9 (d, 1H, H2, J9.6 Hz), 7.7 (d, 2H, H5′, H9′), 8.5 (d, 1H, H1), 8.6 (d, 2H, H6′, H8′) 11.6 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ, 17.4, 17.8 (C10, C8), 25.7, 26.2 (C5, C9), 40.3 (C4), 121.4 to 123.1 (C2, C5′, C9′, C6), 132.5 (C7), 140.4 (C1), 150.1 to 151.6 (C4′, C6′, C8′, C3), 162.9 (C3′).

Partition coefficient oil/water experiments of INH and JVA were determined using dichloromethane (J.T. Baker) as the organic phase (oil) (30). Two milligrams of INH or JVA was transferred to microtubes and dissolved in 1 ml of water and 1 ml of dichloromethane. The mixture was homogenized for 5 min and centrifuged for 1 h at 1,000 × g. After centrifugation, 200 μl of organic phase and 200 μl of aqueous phase were removed, and solutions were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using the chromatographic conditions described below. Drug concentrations were determined in each phase, and the coefficient of oil/water partition (log P) was calculated using this equation: log P = (Co/Ca)r, where Co and Ca are concentrations in oil phase and aqueous phase, respectively, and r is the ratio of volumes between the oil and aqueous phases. Theoretical log P was obtained using online software (Molinspiration).

Preparation of PLGA nanoparticles.

Poly-lactide-coglycolic acid (PLGA) nanoparticles containing INH or JVA were prepared using nanoprecipitation (15) via polymer interfacial deposition. Briefly, organic phase was prepared by dissolving 45 mg of PLGA (502H, 50:50; Mr, 7,000 to 17,000) (Boehringer, Germany) in 3 ml dichloromethane mixed with INH or JVA (10 mg) in ethanol solution (2 ml) (J.T. Baker). This mixture was added into a 10-ml 1% (wt/vol) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Sigma) solution (aqueous phase), sonicated (Unique, Brazil; 50 W for 3 min), and rota-evaporated at 60°C (Quimis, Brazil) for 5 min. The resulting suspension volume was adjusted to 10 ml, and nanoparticles were washed tree times with sterile water and collected by centrifugation (30,900 × g, 60 min at 4°C). Supernatants as well as total nanoparticle suspensions (100 μl) were used to determine the entrapment efficiency as described below. In a set of experiments, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-NPs were obtained as described above using 2 mg of sodium fluorescein (Sigma-Aldrich) mixed with or without JVA as the organic phase.

In a set of experiments, to improve the nanoencapsulation of INH using PLGA, different techniques such as double emulsion (36) and nanoprecipitation with salting out (44) were performed as previously described.

Determination of nanoparticle morphology and surface charge.

Particle size, polydispersity, and zeta potential of nanoparticles were determined using a Zetasizer 3000HS (Malvern Instruments, United Kingdom). For all measurements, each sample was diluted to the appropriate concentration with Milli-Q water. Each size analysis lasted 120 s and was performed at 25°C with an angle detection of 173°. For measurements of zeta potential, nanoparticle samples were placed into the electrophoretic cell, where a potential of ±150 mV was established. The ξ-potential values were calculated from the mean electrophoretic mobility values using Smoluchowski's equation. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) (JSM 6100; Jeol, Japan) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (NanoSurf, Switzerland) were employed to analyze particle morphology. For the microscopic analysis, the diluted solution was cast onto glass substrates (AFM) or onto gold-recovered stubs (FESEM). The AFM image was collected in tapping mode with 512 by 512 lines at a scan rate of 1.0 Hz.

Measurements of drug contents in nanoparticles.

JVA or INH contents were measured by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (AllianceBio system; UV-VIS photodiode array detector SPD-M20A) (Waters Co.). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Luna analytical column (RP-C18; 250 mm by 4.6 mm by 5 μm) (Phenomenex Co.). The detection of JVA (298 nm) or INH (261 nm) was employed using acetonitrile buffer (J.T. Baker) with 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 3.5 (65:35 vol/vol), or acetonitrile buffer with 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 3.5 (03:97 vol/vol), respectively, with an isocratic elution mode at a flow rate of 1 ml · min−1. To measure drug contents within nanoparticles, JVA-NP or INH-NP pellets were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (1 ml) and sonicated for 1 min at 50 W. Drug content (μg · ml−1) measurements from total NP suspensions, NP pellets, or supernatants were obtained in 100-μl aliquots diluted in defined mobile phase following filtration in 0.45-μm membranes. Samples were analyzed in triplicate by HPLC, and drug concentrations were calculated using a standard curve. Entrapment efficiency (EE) was calculated as the difference between the total drug amount (mg) from total NP suspension versus that of supernatants {[total drug amount (mg)] − [supernatant (mg)]/[total drug amount (mg)]} × 100. Drug content was calculated by means of the amount of compound measured in the pellet. The HPLC method was previously validated, and linear calibration curves for JVA and INH were obtained in the range of 1.56 to 100 μg · ml−1, presenting correlation coefficients greater than 0.998 (data not shown).

JVA-NP-macrophage association studies. (i) Flow cytometry.

Murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs; 5 × 105 cells/ml) generated as previously described (4) were infected with M. tuberculosis variant bovis BCG strain Pasteur expressing the red fluorescent protein dsRed1 (BCG-RFP) (1, 14) (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 10) for 3 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES (all from Gibco). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco) and exposed to FITC-NP for 2 h. After that, macrophages were washed with PBS and suspended in PBS–1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (fluorescence-activated cell sorter [FACS] buffer). Cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur or FACSCanto II (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo 8.6.3 software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). To analyze NPs associated with mycobacterium-infected cells, events were first gated on cell populations based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) parameters and then on FL-2 (RFP-BCG)-positive events versus SSC. FL2+ cells were then gated, and FL-1 (FITC-NP) was employed in histograms. In all experiments performed, infected cells untreated or exposed to unlabeled NPs (empty control) were utilized as negative controls and to guide the gating strategy.

(ii) Confocal laser-scanning microscopy.

DMEM-cultured BMMs (5 × 105 cells/ml) adhered onto coverslips were infected with BCG-RFP (MOI, 1) and incubated for 3 h. Macrophages then were washed 3 times with DMEM and exposed to FITC-NPs for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed, labeled with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes), and recovered with antifading reagent (Molecular Probes). Images were acquired on a Leica TCS SP5, which is a confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, IL). Representative cells were selected and a series of optical sections (z sections) were taken. Images captured in DAPI, rRFP, and FITC channels were overlaid to determine the colocalization of FITC-NP as well as BCG-RFP.

(iii) Intracellular bioavailability studies.

Murine BMMs (5 × 105 cells/ml) were exposed to JVA or JVA-NPs (diluted in DMEM) at a final concentration of 200 μg · ml−1 of JVA. Following 3 h of incubation, cells were washed five times with PBS and lysed by six cycles of freeze-thawing. JVA extraction from cell lysates was performed as previously described (48), with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 μl of 20% (wt/vol) NaCl solution was added to 200 μl of cell lysate. After the addition of chloroform-butanol (70:30, vol/vol) (1 ml), cell lysates were vortexed for 1 min followed by centrifugation (4,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature). Two hundred μl of aqueous phase was discarded, and the remaining organic phase was analyzed by HPLC as described above.

(iv) Antimycobacterial activity by infected macrophages.

BMMs (5 × 105 cells/ml) were infected with the virulent strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv (MOI, 1) at 37°C containing 5% CO2 for 4 h in complete DMEM. Cells then were washed with PBS, and new media without antibiotics were added to cultures, which were exposed to JVA or JVA-NPs (diluted in DMEM). After 7 days of incubation, the medium was removed and cells were washed and lysed using 200 μl of 1% saponin in sterile water. Cell lysates were plated on solid medium 7H10 and incubated at 37°C. After 28 days of incubation CFU were counted, and the results were expressed graphically.

JVA-NP-mycobacterium association studies. (i) Flow cytometry.

One hundred μl of M. tuberculosis H37Rv suspension (106 bacteria/well) cultured in Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium, 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) was added to 15-ml tubes (Falcon; BD) and exposed to NPs (nanoparticles without drug) or FITC-NPs (20 μl) for 4 h. Bacterial suspensions were washed 3 times with PBS to remove nonassociated particles and suspended in FACS buffer containing 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). Events were acquired on a FACSCalibur or FACSCanto II (BD) flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo 8.6.3 software. To analyze M. tuberculosis, samples were first gated on cell populations based on FSC and SSC parameters and then on FL-1 (FITC-NP) events versus SSC. In all experiments performed, unlabeled M. tuberculosis cells were utilized as negative controls and to guide the gating strategy.

(ii) Atomic force microscopy.

M. bovis BCG (2 × 104 bacteria/ml) was incubated with 500 μl of JVA-NPs or NPs (200 μg · ml−1) for several time points at 37°C, 5% CO2. After that, bacterial suspensions were washed 3 times with Milli-Q water and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was suspended in 1 ml of Milli-Q water, and samples were prepared by pipetting 20 μl in coverslips. Images were acquired on an SPM-9600 atomic force microscope (Shimadzu, Japan) using dynamic/phase mode with a 125-μm-length cantilever (spring constant of ∼42 N/m, resonant frequency of ∼250 kHz) with conical tips (curvature radius of <10 nm). Images were acquired as 512 by 512 lines at a scan rate of 1.0 Hz. All images were processed using the SPM-9600 off-line software (Shimadzu, Japan). The processing consisted of an automatic global leveling, and the images were displayed as two-dimensional (2D) (phase) and 3D (height) representations, which were utilized to perform measurements of surface height as well as to determine the relative viscosity of NPs associated with mycobacteria.

(iii) Antimycobacterial activity.

M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv was cultured in LJ medium and incubated for 4 weeks at 37°C. Bacterial suspensions in 7H9 broth were prepared by the disruption of M. tuberculosis in glass beads. The M. tuberculosis concentration was determined by a number 1 McFarland scale equivalent to 3 × 108 bacteria · ml−1. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was carried out as previously described (33), with minor modifications. Briefly, each well of a 96-well plate received 100 μl of different concentrations of INH, JVA, or JVA-NPs diluted in culture medium containing 1% Tween (Sigma-Aldrich). One hundred μl of bacterial suspension (106 bacteria/well) was added and plates incubated at 37°C for several time points. After that, 50 μl of the MTT solution was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Fifty μl of lysing buffer containing 20% SDS in 50% N1N-dimethylformamide (pH 4.7) then was added to each well, and plates were incubated overnight. Absorbance (540 nm) was measured in an automatic microplate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan, Germany). In a set of experiments following drug or drug-NP treatment, mycobacterial samples were plated on solid medium 7H10 and incubated at 37°C. After 28 days of incubation, CFU were counted and the results were expressed graphically.

(iv) NP-M. tuberculosis interaction studies by MALDI-TOF/MS.

Mycobacterium-NP suspensions (2 × 104 CFU/ml incubated with 500 μl of JVA-NPs or controls) were washed with Milli-Q water, centrifuged (10,000 × g for 10 min), and applied as pellets onto a 0.45-μm-membrane filter system (Millipore). After that, membranes were extensively washed with Milli-Q water (30 times) in which the retentate consisted of mycobacteria or mycobacterium-NP, and the flowthrough consisted of nonassociated NPs or free JVA. Membranes containing the retentate then were placed onto plastic tubes and mixed with a saturated matrix solution of alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (1:3) and spotted (0.5 μl) onto an MTP AnchorChip var/384 matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) sample plate. The monoisotopic molecular mass of the JVA was determined by MALDI–time of flight tandem mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/MS) using an UltraFlex III (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) controlled by FlexControl 3.0 software. The MS spectra were carried out in the positive ion reflector mode at a laser frequency of 100 Hz with external calibration using the matrix ions. Data were analyzed using FlexAnalysis 3.0 software.

Statistical analysis.

Nonparametric Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (Graphpad Software, Prism) was used to calculate the significance of differences between groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

JVA, a hydrophobic citral-derived INH analogue, displays antimycobacterial activity and high entrapment efficiency in PLGA nanoparticles.

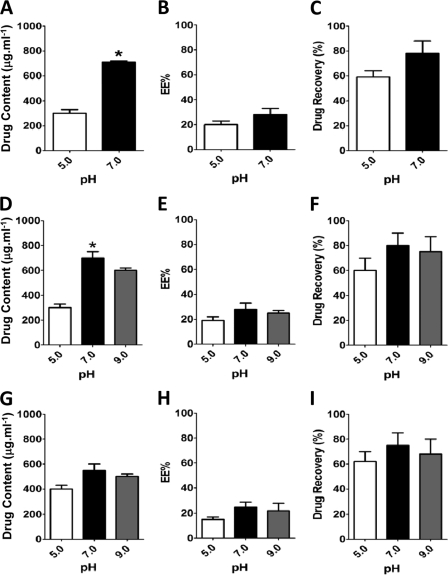

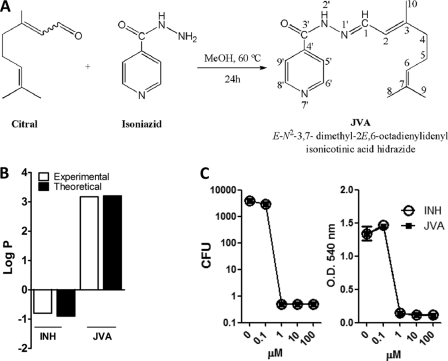

To study NP-antibiotic-mycobacterium-phagocyte interactions, we first employed known techniques to nanoencapsulate INH using the approved PLGA polymer (Fig. 1). However, we consistently observed that this antimycobacterial drug presented a low entrapment efficiency (∼20%) within the PLGA-NPs (Fig. 1). INH is a known hydrophilic molecule, and although it has long been used as an effective anti-TB drug, its low cellular penetration could contribute to the development of M. tuberculosis resistance (8, 26, 35). Therefore, the development of hydrophobic INH analogues could both enhance nanoencapsulation in PLGA-based particles (32) and increase the cellular penetration of target tissues (8, 23, 25). We next aimed to increase drug hydrophobicity, and to do so we treated INH with citral in methanol to generate the corresponding hydrazine, E-N2-3,7-dimethyl-2-E,6-octadienylidenyl isonicotinic acid hydrazide, named JVA (Fig. 2A) (20), which presents a high partition coefficient (log P) (Fig. 2B). JVA displays mycobacterial killing activity similar to that of INH as analyzed by means of CFU counts on agar plates or MTT-based assay in broth media (Fig. 2C), indicating that this compound is a candidate to generate novel nanoenabled delivery systems against TB. PLGA-based nanoparticles displayed large amounts of JVA (4-fold increase above that of INH) as well as the enhanced entrapment efficiency of this compound (3-fold increase above that of INH) (Fig. 3A and B). Drug recovery for JVA-NPs and INH-NPs was found to present similar results (80 and ∼65%, respectively) (Fig. 3C). The average diameter of JVA-NPs was approximately 180 nm with monomodal distribution (polydispersity index, <0.2; data not shown) as well as negative surface charge (−23 ± 0.9mV) (Fig. 3D and E). Evaluations employing field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) analyses have revealed the spherical shape and smooth surface of JVA-NP formulations (Fig. 3F to I). Moreover, detailed FESEM measurements showed that JVA-NPs presented a characteristic core shell particle, suggesting that this drug is entrapped within the nanoparticle (Fig. 3G) and that this nanosystem could enhance bacterial killing inside or outside phagocytes.

Fig 1.

Nanoencapsulation of the hydrophilic antimycobacterial drug isoniazid. Nanoparticles containing INH were prepared as described in Materials and Methods, and drug content (μg ml−1) (A, D, and G), entrapment efficiency (%) (B, E, and H), and drug recovery (%) (C, F, and I) were determined by RP-HPLC following several technical procedures and external-phase pH variation. (A to C) Double emulsion technique; (D to F) nanoprecipitation; (G to I) nanoprecipitation salting-out procedure using NaCl. Results are means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of measurements from triplicates. The results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments performed. An asterisk indicates statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by Student's t test) in measurements between pH 5.0 and 7.0.

Fig 2.

Antimycobacterial activity of JVA, a highly hydrophobic isoniazid analogue. (A) Preparation of JVA. (B) Partition coefficient (log P) (dichloromethane/water) of INH and JVA as described in Materials and Methods. (C) M. tuberculosis H37Rv cultures were exposed to different concentrations of INH or JVA for 7 days, and bacterial viability was determined by CFU counts or MTT-based assay (right) as described in Materials and Methods.

Fig 3.

Increased entrapment efficiency and JVA contents within PLGA-NP. Nanoparticles containing JVA or INH were prepared as described in Materials and Methods, and drug content (μg ml−1) (A), entrapment efficiency (%) (B), and drug recovery (%) (C) were determined by RP-HPLC. Nanoparticle diameter (nm) (D) and zeta potential (mV) measurements (E) were made on a Zetasizer. Results are means ± SEM of measurements from triplicates. The results shown are representative of 10 independent experiments performed. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by Student's t test) in measurements between JVA-NP and INH-NP. Representative images from FESEM (F and G) and AFM (H and I) of JVA-NP were generated as described in Materials and Methods. (G) Detailed image of a single nanoparticle demonstrating a central core (JVA) and a polymeric shell.

JVA-NPs enhance mycobacterial killing by macrophages and promote drug intracellular bioavailability.

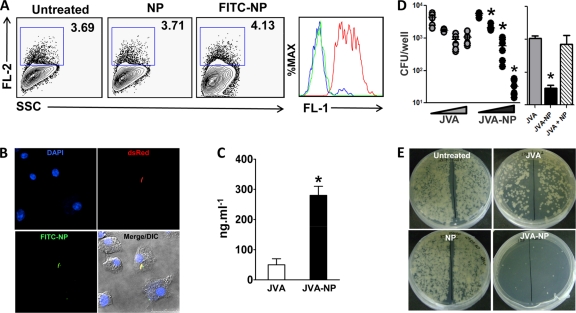

During active infection, proliferating M. tuberculosis bacilli are found in intracellular compartments of macrophages as well as in the extracellular milieu (19, 35). To examine whether JVA-NPs are functional nanocarriers, we first studied NP-macrophage interactions. Flow cytometry and confocal microscopy analyses demonstrate that BCG-RFP-infected macrophages uptake FITC-stained NPs (Fig. 4A and B). Moreover, FITC-NPs were found to colocalize with BCG-RFP inside macrophages (Fig. 4B), suggesting that such nanocarriers directly interact with intracellular bacteria, promoting increased drug bioavailability in infected tissues. Consistently with this, increased amounts of JVA inside macrophages were found when cells were treated with JVA-NPs in vitro (Fig. 4C). Strikingly, compared to soluble JVA, JVA-NP treatment enhanced M. tuberculosis killing by macrophages in a dose-response manner (Fig. 4D and E). In addition, M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages exposed to a mixture of soluble JVA and NPs (JVA + NP), as opposed to nanoencapsulated JVA (JVA-NP), display levels of mycobacterial killing comparable to those found in cells treated with soluble JVA (Fig. 4D, right). Taken together, these results indicate that JVA-NPs target intracellular M. tuberculosis and promote antibiotic delivery into macrophages.

Fig 4.

JVA-NPs enhance mycobacterial killing by macrophages and promote increased drug intracellular bioavailability. (A) BCG-RFP-infected macrophages were exposed to FITC-NPs for 1 h. Following washes, cells were acquired in a flow cytometer and dot plots generated in FlowJo as described in Materials and Methods. The histogram on the right demonstrates FITC-NP (FL-1) associated with mycobacterium-infected macrophage gated on FL-2+ events. Green line, untreated; blue line, NP; red line, FITC-NP. (B) Confocal microscopy images of mycobacteria (RFP, red)-infected macrophages exposed to FITC-NPs. DAPI was used to stain nuclei. (C) BMM were treated with JVA or JVA-NP for 3 h, and the intracellular drug content was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results represent means ± SEM of measurements from two experiments. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05, Student's t test) in measurements between JVA and JVA-NP. (D) M. tuberculosis H37Rv-infected macrophages were left untreated or were exposed to increased concentrations (0, 3, 30, or 300 μM) of JVA or JVA-NP for 7 days, and CFU counts were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Results represent pooled data from three independent experiments. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA) in measurements between the different concentrations of JVA-NP (dose-response curve). The image on the right demonstrates the experiment described, in which cells were treated with JVA, JVA-NP, or a mixture of JVA with NPs (300 μM drug). (E) Representative CFU plates from experiment described for panel D. DIC, differential interference contrast.

JVA-NPs directly enhance drug delivery in mycobacteria.

Because proliferating mycobacteria are also observed outside cells (19, 35), an efficient nanoenabled system should be able to both interact and deliver anti-TB drugs in such an environment. Figure 5A shows that FITC-stained NPs directly associate with M. tuberculosis. This was further demonstrated by AFM analysis of JVA-NPs and mycobacterial interaction experiments (Fig. 5B, right top). Moreover, by employing phase images (viscoelasticity) in JVA-NP-treated mycobacteria, we have observed that such carriers directly interact with the bacilli (Fig. 5B, right bottom). Detailed measurements of height profiles as well as relative viscosity performed in mycobacterial cell wall surfaces confirm the presence of nanoparticles (Fig. 5C and D). Similarly to what was observed in M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages (Fig. 4D and E), JVA-NPs inhibited M. tuberculosis growth in both time- and dose-dependent manners (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that the nanobased system JVA-NPs diminish pathogen proliferation by enhancing drug bioavailability in the bacterium. To test such a hypothesis, mycobacteria were left untreated or were exposed to soluble JVA or JVA-NPs. Following 1 h of incubation, samples were applied onto a 0.45-μm membrane filter system in which a set of extensive washes (30 times) have been employed to discard possible nonassociated NPs and drug (flowthrough). MALDI-TOF was employed in the membrane/retentate system (i.e., mycobacterium-associated NPs) to detect bacterially bound JVA ions. Importantly, high contents of ion JVA (m/z 272) remained detectable in the membrane from JVA-NP-mycobacterium samples compared to those exposed to soluble JVA (Fig. 5F) or a control in which only JVA-NPs were directly applied to the membrane filter system. Taken together, these results suggest that nanoparticles directly interact with mycobacteria and could enhance drug delivery within the pathogen.

Fig 5.

JVA-NP directly interacts with mycobacterial cell wall and enhances JVA delivery. (A) M. tuberculosis was exposed to FITC-stained NPs for 4 h. Samples were acquired by flow cytometry, and dot plots were generated in FlowJo as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Strain BCG cells were left unexposed or were exposed to JVA-NP for 1 h, and images were acquired by atomic force microscopy (AFM). (C) Line profile and (D) relative viscosity obtained by AFM from samples described for panel B. Results represent means ± SEM of measurements from two experiments performed. An asterisk indicates statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Student's t test) in measurements between untreated and JVA-NP groups. (E) M. tuberculosis H37Rv suspensions were exposed to JVA-NP for several times points and different drug concentrations. Results represent means ± SEM of measurements from triplicates. Data shown are representative of at least three experiments. (F) BCG cells were exposed to JVA-NP for 1 h, extensively washed, and filtered onto a 0.45-mm membrane as presented in the schematic. Mycobacterial NPs trapped in the membranes were analyzed by MALDI-TOF/MS. Results represent means ± SEM of measurements from sextuplicates. An asterisk indicates statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA) in measurements between JVA-NP versus untreated or JVA groups.

DISCUSSION

The use of nanotechnology has been proposed to generate novel biodegradable nanoparticle-based anti-TB drug delivery systems (7, 18, 45). Such nanosystems are thought to target drug into M. tuberculosis-infected phagocytes and improve drug control release into infected tissues (27, 37). However, to develop ideal nanocarriers against TB, detailed analysis of the molecular pathways associated with nanoparticle drug-M. tuberculosis cell interactions may be helpful to rationally design effective nanoenabled systems. In the present study, we have developed a PLGA nanoenabled delivery system containing an INH analogue which enhances M. tuberculosis killing whether bacteria are located inside macrophages or outside these cells. Although INH has been utilized since 1952, this molecule is highly hydrophilic, and it is thought that it should not be used alone for TB treatment given its low cellular penetration, which is associated with the induction of bacterial resistance (26, 35). Nevertheless, INH displays a low MIC (0.05 μg · ml−1), and it has been speculated that INH analogues can be further utilized to increase activity and cellular penetration (8, 25). Additionally, the use of novel analogues based on old molecules is a general idea to reduce time to generate novel TB chemotherapy. We have developed a highly hydrophobic compound, E-N2-3,7-dimethyl-2-E,6-octadienylidenyl isonicotinic acid hydrazide, named JVA, which was found to be significantly encapsulated in PLGA nanoparticles. Using a similar method to generate Schiff bases of INH, Hearn et al. have independently found an identical molecule with in vitro antimycobacterial activity (20). Consistently with this, we have observed that JVA inhibits the growth of the virulent H37Rv strain in vitro at levels comparable to those of INH (Fig. 2C). Although we have not directly addressed the mechanism by which JVA decreases mycobacterial proliferation in vitro, it appears that this compound displays an effect similar to that of INH, since a clinical INH-resistant M. tuberculosis isolate (KatG S315T) was also resistant to JVA (data not shown). However, it is still possible that different mechanisms are involved in the observed mycobacterial killing by JVA, and therefore its mechanism of action remains to be fully elucidated. Theoretical and experimental analysis of JVA demonstrated partition coefficients (log P) of 3.174 and 3.203, respectively (Fig. 2B), values known to be associated with high levels of drug encapsulation in hydrophobic polymers such as PLGA (37). Taken together, these results suggest that this molecule could be further evaluated in preclinical studies. Moreover, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of JVA as a potential therapeutic target in TB merit further investigation.

As expected, employing nanoprecipitation-based techniques to develop PLGA nanoparticles containing JVA has shown enhanced contents of JVA encapsulation compared to that of INH. Several drug nanoencapsulation-based techniques, such as double emulsion, nanoprecipitation, and nanoprecipitation-salting out, have demonstrated various levels of INH encapsulation due to its high hydrophilicity (2, 37). In contrast, we have found that JVA presents 70 to 80% entrapment efficiency (Fig. 3B) and 4 times the drug content of INH, which shows only 20% efficiency in the same conditions. Interestingly, INH has been shown to present high entrapment efficiency in some but not all cases (2, 7), which could be explained by the use of diverse polymer and nanotechnology-based techniques (32, 37). In the present study, although we have performed different techniques and changed a number of conditions, such as pH, temperature, external phase, and polymer (Fig. 1 and data not shown), we have failed to enhance INH entrapment efficiency above 20% in PLGA particles. Nevertheless, lower levels of INH entrapment efficiency have been observed by others (2, 12), and it is well accepted in the literature that hydrophilic molecules display low entrapment efficiency in polymeric PLGA system-derived nanoparticles (17, 32). Although both soluble JVA and INH display similar MICs (1 μM), the JVA-NP MIC was found to be 3 times lower than that of INH-NPs (1.0 and 3.0 μM, respectively) (data not shown), suggesting that our novel nanoenabled system increases delivery to the pathogen compared to that of nanoencapsulated INH. Therefore, aiming for more consistent results, we have further analyzed NP-M. tuberculosis interactions using the JVA molecule as an anti-TB candidate model.

We observed that the nanoenabled system using JVA within PLGA nanoparticles enhanced M. tuberculosis killing inside macrophages. This effect was associated with increased interactions of JVA-NPs and bacteria as well as enhanced intracellular drug bioavailability. Intracellular analysis using confocal microscopy demonstrated that FITC-stained nanoparticles colocalize with mycobacteria, suggesting that such a nanocarrier traffics to bacterially associated phagosomes. Although we have not directly investigated whether nanocarriers of PLGA-JVA present enhanced intracellular interactions by macrophages, our data suggest that nanoparticles gain access to compartments containing mycobacteria. This hypothesis is supported by observations showing nanoparticles located in nearby points where bacteria are present but not in uninfected cells, which demonstrates the intracellular spreading of nanoparticles (Fig. 4B). These experiments suggest that infected macrophages are targeted with nanoparticle-containing antibiotics, as recently suggested by Lawlor et al. (27). Consistently with this, flow cytometry data demonstrated that NP-FITC is found in BCG-RFP-infected cells (Fig. 4A). Moreover, compared to soluble JVA, the treatment of M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages with JVA-NPs was found to enhance bacterial killing, suggesting that nanocarriers closely interact with pathogens inside the phagocytes. A detailed study on how nanoparticles containing antibiotics gain access to M. tuberculosis phagosomes remains to be performed. Nevertheless, recent data have emerged in the literature exploring intracellular pathways and mechanisms by which nanoparticles are endocytosed (22, 52). Although we have not studied other mechanisms by which JVA-NPs decrease M. tuberculosis survival inside macrophages, it is possible that antibiotic nanoparticles induce cell apoptosis (51), which is known to restrict intracellular virulent M. tuberculosis growth (6). Nevertheless, our results (see the supplemental material) show no difference in macrophage necrosis/apoptosis or cell toxicity by JVA-NP compared to that of the soluble drug, suggesting that the observed effect in intracellular mycobacterial growth in vitro is not due to cell death. However, since the dynamics of macrophage apoptosis during infection may change following drug treatment, a more detailed analysis of the role of cell death in bacterial survival should be performed using inhibitors of apoptosis-associated pathways.

JVA-NPs directly interact with M. tuberculosis. Moreover, JVA was found to be associated with mycobacterial cell walls following exposure to JVA-NPs, suggesting that drug delivery is enhanced in bacterial cultures exposed to nanocarriers. Taken together, these data demonstrate that it is possible to generate nanosystems to target intra- and extracellular mycobacteria, which could contribute to increase bacterial killing within granulomas at lower drug doses. Although we have not investigated the ultrastructure of mycobacteria treated with JVA-NP, it has been previously demonstrated that antibiotic treatment promotes changes in the bacterium (3, 47). Moreover, physical and biochemical mechanisms by which JVA-NP interacts with M. tuberculosis merits further investigation. Based on our evidence, we speculate that it is possible that PLGA nanoparticles directly access the mycobacterial membrane, enhancing intracellular drug bioavailability.

Our findings demonstrate the development of nanoenabled anti-TB systems that enhance drug targeting in extra- or intracellular mycobacteria, probably due to direct interactions between nanoparticles and the bacilli. These observations suggest that it is critical that we understand M. tuberculosis-nanoparticle interactions as a potential pharmacologic intervention for enhancing the control of pathogen replication during active TB. In this regard, it should be noted that nanocarrier systems are already in clinical trials for cancer and some infectious diseases (29, 38), therefore it may be possible to generate nanoenabled anti-TB systems to test the efficacy of this strategy for intervention in TB.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by CAPES/NANOBIOTEC (NANOTB 23038.021356 and 23038.019088 and NANOBIOMED 705/2009), CNPq (Universal 477857, 507205, and 576948), and FIOCRUZ. M.J.S., L.P.S., M.V.A., and A.B. are investigators of CNPq (PQ-CNPq).

We thank Anicleto Poli, Marta E. R. Dosso, and Jonatan Ersching for helpful advice and technical support during the development of this work. We thank the UFSC Microscopy Center and LAMEB-CCB personnel for technical assistance.

We have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 February 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abadie V, et al. 2005. Neutrophils rapidly migrate via lymphatics after Mycobacterium bovis BCG intradermal vaccination and shuttle live bacilli to the draining lymph nodes. Blood 106:1843–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ain Q, Sharma S, Garg SK, Khuller GK. 2002. Role of poly[DL-lactide-co-glycolide] in development of a sustained oral delivery system for antitubercular drug(s). Int. J. Pharm. 239:37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alsteens D, et al. 2008. Organization of the mycobacterial cell wall: a nanoscale view. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 456:117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bafica A, et al. 2005. TLR9 regulates Th1 responses and cooperates with TLR2 in mediating optimal resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 202:1715–1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barry CE, III, Blanchard JS. 2010. The chemical biology of new drugs in the development for tuberculosis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14:456–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Behar SM, Divangahi M, Remold HG. 2010. Evasion of innate immunity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: is death an exit strategy? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:668–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blasi P, Schoubben A, Giovagnoli S, Rossi C, Ricci M. 2009. Fighting tuberculosis: old drugs, new formulations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 6:977–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Budha NR, Lee RE, Meibohm B. 2008. Biopharmaceutics, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antituberculosis drugs. Curr. Med. Chem. 15:809–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cooper AM, Mayer-Barber KD, Sher A. 2011. Role of innate cytokines in mycobacterial infection. Mucosal Immunol. 4:252–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Noronha AL, Báfica A, Nogueira L, Barral A, Barral-Netto M. 2008. Lung granulomas from Mycobacterium tuberculosis/HIV-1 co-infected patients display decreased in situ TNF production. Pathol. Res. Pract. 204:155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dorhoi A, Reece ST, Kaufmann SH. 2011. For better or for worse: the immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis balances pathology and protection. Immunol. Rev. 240:235–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dutt M, Khuller GK. 2001. Sustained release of isoniazid from a single injectable dose of poly (D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles as a therapeutic approach towards tuberculosis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 17:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dye C, Williams BG. 2010. The population dynamics and control of tuberculosis. Science 328:856–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Egen JG, et al. 2008. Macrophage and T cell dynamics during the development and disintegration of mycobacterial granulomas. Immunity 28:271–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fessi H, Puisieux F, Devissaguet JP, Ammoury N, Benita S. 1989. Nanocapsule formation by interfacial polymer deposition following solvent displacement. Int. J. Pharm. 55:R1–R4 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gandhi NR, et al. 2010. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a threat to global control of tuberculosis. Lancet 375:1830–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Govender T, Stolnik S, Garnett MC, Illum L, Davis SS. 1999. PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nanoprecipitation: drug loading and release studies of a water soluble drug. J. Control Release 57:171–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griffiths G, Nyström B, Sable SB, Khuller GK. 2010. Nanobead-based interventions for the treatment and prevention of tuberculosis. Nat. Ver. Microbiol. 8:827–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grosset J. 2003. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the extracellular compartment: an underestimated adversary. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:833–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hearn MJ, et al. 2009. Preparation and antitubercular activities in vitro and in vivo of novel Schiff bases of isoniazid. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 44:4169–4178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Helke KL, Mankowski JL, Manabe YC. 2006. Animal models of cavitation in pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 86:337–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hillaireau H, Couvreur P. 2009. Nanocarriers' entry into the cell: relevance to drug delivery. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66:2873–2896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Honeybourne D. 1994. Antibiotic penetration into lung tissues. Thorax 49:104–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koul A, Arnoult E, Lounis N, Guillemont J, Andries K. 2011. The challenge of new drug discovery for tuberculosis. Nature 469:483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kumar A, Patel G, Menon SK. 2009. Fullerene isoniazid conjugate–a tuberculostat with increased lipophilicity: synthesis and evaluation of antimycobacterial activity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 73:553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lambert PA. 2002. Cellular impermeability and uptake of biocides and antibiotics in Gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92(Suppl.):46S–54S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lawlor C, et al. 2011. Cellular targeting and trafficking of drug delivery systems for the prevention and treatment of M. tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 91:93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Look M, Bandyopadhyay A, Blum JS, Fahmy TM. 2010. Application of nanotechnologies for improved immune response against infectious diseases in the developing world. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 62:378–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mallipeddi R, Rohan LC. 2010. Progress in antiretroviral drug delivery using nanotechnology. Int. J. Nanomed. 5:533–547 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mehta SK, Kaur G, Bhasin K. 2007. Incorporation of antitubercular drug isoniazid in pharmaceutically microemulsion: effect on microstructure and physical parameters. Pharm. Res. 25:227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mitchison DA. 2000. Role of individual drugs in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung. Dis. 4:796–806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mora-Huertas CE, Fessi H, Elaissari A. 2010. Polymer-based nanocapsules for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 385:113–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mshana RN, Tadesse G, Abate G, Miörner H. 1998. Use of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide for rapid detection of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1214–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nathan C, et al. 2008. A philosophy of anti-infectives as a guide in the search for new drugs for tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 88(Suppl. 1):S25–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nuermberger E, Grosset J. 2004. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic issues in the treatment of mycobacterial infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 23:243–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pandey R, Zahoor A, Sharma S, Khuller GK. 2003. Nanoparticle encapsulated antitubercular drugs as a potential oral drug delivery system against murine tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 83:373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pandey R, Ahmad Z. 2011. Nanomedicine and experimental tuberculosis: facts, flaws, and future. Nanomedicine 7:259–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peer D, et al. 2007. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2:751–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reichman LB, Hershfield ES. 1993. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is particularly susceptible to isoniazid [isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH)], the most widely used of all antitubercular drugs, p 207–240 In O'Brien J. (ed.), Lung biology in health and disease, vol 66 Dekker, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rivers EC, Mansera RL. 2008. New anti-tuberculosis drugs in clinical trials with novel mechanisms of action. Drug Discov. Today 13:1090–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Russell DG, Barry CE, III, Flynn JL. 2010. Tuberculosis: what we don't know can, and does, hurt us. Science 328:852–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. 2007. Malnutrition and infection: complex mechanisms and global impacts. PLoS Med. 4:e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sharma A, Pandey R, Sharma S, Khuller GK. 2004. Chemotherapeutic efficacy of poly (dl-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticle encapsulated antitubercular drugs at sub-therapeutic dose against experimental tuberculosis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 24:599–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Song X, et al. 2008. Dual agents loaded PLGA nanoparticles: systematic study of particle size and drug entrapment efficiency. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 69:445–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sosnik A, Carcaboso AM, Glisoni RJ. 2010. New old challenges in tuberculosis: potentially effective nanotechnologies in drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 62:547–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vandal OH, Nathan CF, Ehrt S. 2009. Acid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 191:4714–4721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Verbelen C, et al. 2006. Ethambutol-induced alterations in Mycobacterium bovis BCG imaged by atomic force microscopy. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264:192–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Verma RK, Kaur J, Kumar K, Yadav AB, Misra A. 2008. Intracellular time course, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution of isoniazid and rifabutin following pulmonary delivery of inhalable microparticles to mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3195–3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. World Health Organization 2011. Global tuberculosis control: WHO reports 2010. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241564069_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 50. World Health Organization 2011. Multidrug and extensive drug resistant tuberculosis: 2010 global report on surveillance and response. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599191_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yadav AB, Misra A. 2007. Enhancement of apoptosis of THP-1 cells infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis by inhalable microparticles and relevance to bactericidal activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3740–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhao F, et al. 2011. Cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and cytotoxicity of nanomaterials. Small 7:1322–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.