Abstract

It is widely accepted that the brain responds to mechanical trauma and development of most neurodegenerative diseases with an inflammatory sequelae that was once thought exclusive to systemic immunity. Mostly cationic peptides, such as the β-defensins, originally assigned an antimicrobial function are now recognized as mediators of both innate and adaptive immunity. Herein supporting evidence is presented for the hypothesis that neuropathological changes associated with chronic disease conditions of the CNS involve abnormal expression and regulatory function of specific antimicrobial peptides. It is also proposed that these alterations exacerbate proinflammatory conditions within the brain that ultimately potentiate the neurodegenerative process.

1. Introduction

Chronic activation and impaired regulation of the innate immune response within the brain has been proposed by Fernández et al. [1] as a primary, unifying cause of Alzheimer's disease (AD) [2]. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are important components of the innate immune system and also have been shown to function as regulators of the adaptive immune system [3, 4]. Williams [5] proposed that these agents may underlie neuropathologies within the human brain associated with neurodegenerative disease, aging, diabetes mellitus, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) [6]. The most extensively studied AMPs are the human β-defensins (hBDs), and the cathelicidin LL37/hCAP18, the principal candidate immunoregulators in extracerebral tissues [7, 8]. Herein, we present the hypothesis, based primarily on findings from extracerebral tissues, that AMPs also play a functional role in the human brain [9, 10]. Although speculative, we hope that this postulate will contribute to expanding future research into AMP function within the brain.

A proinflammatory state within the brain is a known consequence of TBI [11], neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD) [12], senescence [13], and diabetes mellitus [14]. Despite intense research, neuroinflammatory-associated mechanisms that may underlie neuronal injury remain poorly understood. The human β-defensin peptides hBD-1 and hBD-2 have been isolated, and two genes encoding homologous β-defensin-1 and -2 (rBD-1 and rBD-2) have been identified in the rat [15]. The presence of LL37 in serum and cerebrospinal fluid extracted from patients with bacterial meningitis has also been reported. This peptide has been localized in astrocytes and microglial cells in a pneumococcal meningitis rat model [16]. β-defensins have been hypothesized to play a role in the etiology of neurodegeneration with a focus on traumatic brain injury, a risk factor for AD [17]. Moderate-to-severe TBI induces neuropathological responses that are similar to changes described in the AD brain, including development of chronic inflammation and hyperglycemia [18–22].

2. Hypothesized Role of β-Defensin Antimicrobial Peptides in Proinflammatory Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration

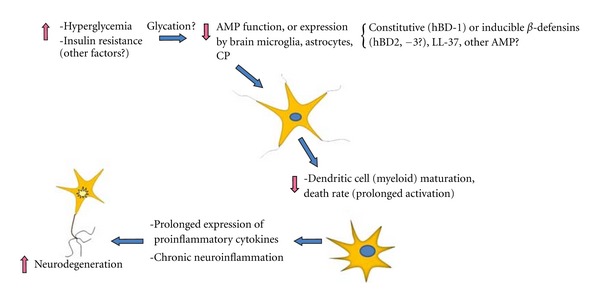

The β-defensins-1, -2, and -3 are recognized as principal regulators of immune response and inflammation [23–25]. Here, we propose that central to impairment of the innate and adaptive immune response, and thus prolongation of inflammation within the brain, is a dysregulation of specific AMP function, including constitutive and inducible β-defensin peptides (Figure 1). Attenuation in function may be attributed to an a priori development of an insidious condition, such as hyperglycemia and/or increased insulin resistance, a component of many neuropathological conditions including AD [26], Huntington's disease [27], aging of the brain [28], diabetes mellitus [29, 30], and TBI [31]. Reduced expression of hBD-2 and -3 mRNA occurs in vitro subsequent to exposure of human primary epithelial cells to high glucose (30 mM) and/or low insulin (<5 μg/mL) (Williams, unpublished). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that dysregulated expression of constitutively expressed AMPs like hBD-1 [32], specific inducible hBDs, including hBD-2 and-3, and perhaps other AMPs such as LL-37 [33], all potential modulators of inflammation, may occur in the traumatized brain and in brain tissue exhibiting chronic inflammation-associated neurodegeneration, as is observed in AD. Conversely, abnormally high levels of AMPs could also contribute to elevated and prolonged inflammation within susceptible brain regions. Chronic hyperglycemia could potentially contribute to glycation (see Figure 1) of specific amino acid residues on AMPs with formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), conformational change, and ultimately inhibition of or prolongation of AMP function [34]. The intensity of a proinflammatory process subsequent to altered AMP expression level and/or function most likely would reflect the combined effects of multiple factors including the level of inflammatory cell activation, inflammatory cell density and rate of cell turnover, and effectiveness of compensatory anti-inflammatory modulators such as microglial intervention and upregulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 [35]. Thus, the induction of inflammation within susceptible brain regions of chronic diabetics presenting with poor glycemic control (hyperglycemic) and in chronic neurodegenerative diseases may exhibit chronic, but low-grade inflammation [36, 37] that may not be substantially greater than that observed in more acute models of inflammation.

Figure 1.

It is hypothesized that reduction or abnormal elevation of AMP expression by brain microglia, astrocytes, or choroid plexus epithelium (CP) may contribute to loss of AMP-induced regulation of dendritic cell maturation and activity. Prolonged and elevated dendritic cell activity could in turn contribute to chronic release of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, etc.) that ultimately promote neuronal cell injury and death. Hyperglycemia-induced glycation of specific AMPs may inhibit antimicrobial and immunomodulatory function.

3. Mild TBI and More Severe Head Trauma Induce Cellular Injury and an Inflammatory Response in the Brain

Neuropathological alterations in neurons are sustained not only in moderate and severe TBI, but also in mild TBI, as indicated by metabolic depression indicative of neuronal injury [38], and other metabolic abnormalities [39–41]. Immune response and inflammation are considered primary to the progression of closed head injury, yet underlying mechanisms are not well understood. It is now recognized that immune function and immunomodulatory capacity are not limited to those cells classically defined as “immune” cells; so-called “nonimmune” cells also are critical to the immune response. In the brain, astrocytes, epithelium of the choroid plexus, and meningothelial cells express and likely secrete immunomodulatory antimicrobial peptides, including hBDs-1 and -2, that could influence inflammation within the brain [9, 42]. Astrocytes, for instance, are capable of responding to bacterial pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus [43]. The responsiveness of these cells may be region specific, as is the case with regional responsiveness to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and basal profile of induced cytokine expression [44–46]. Thus, astrocytes, although not immune cells according to classical definition, may significantly affect central nervous system (CNS) immune response in the pathological state, not only by variable expression and release of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, but also by expression of immunomodulating AMPs [47–50].

Because of the dynamic nature of the response and the complexity of functional interrelationships between expressed immunomodulators, the role that the innate immune response and inflammation play in neuropathology remains ill-defined. Some components of the immune response, including cell-mediated immunity concurrent with reduced levels of key immunoregulatory cytokines, may be suppressed leading to exacerbated inflammation following severe head injury [51], and perhaps in neurodegenerative diseases in general. Still unclear is how the immune response contributes to secondary brain injury following TBI, and to what extent components of the response mediate not only neuronal, but also astrocytic damage. Although specific cytokines may be expressed at reduced levels following TBI, the development of secondary and tertiary changes in brain cell function can be accompanied by increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines. For example, upregulation of interleukin-1 (IL-1α and β) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, both components of the chronic inflammatory response, occurs with onset of depression [52, 53] and headache [54]; both are frequently described as late clinical sequelae of TBI.

TBI induces a cell-mediated immune response within the brain and systemic circulation [55]. Under physiological conditions, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) limits movement of immunocompetent cells into the brain thus regulating the immunological response [56]. TBI-induced disruption of the BBB can lead to unregulated translocation of leukocytes, including monocytes, into the affected brain region with subsequent activation of microglia and astrocytes [57], concomitant with elevated expression of proinflammatory cytokines [58, 59]. However, both astrocytes and microglia also can limit or actively suppress inflammation by the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10, thereby affecting the immunosuppressive response with neuroprotective consequences [48, 60, 61].

4. TBI-Induced Hyperglycemia Exacerbates Cellular Damage and Inflammation in the CNS

Acute hyperglycemia is a component of the normal stress response and can exacerbate brain injury by promoting oxidative stress [62] with potentiation of the inflammatory response [63–65]. Overall, neurological outcome worsens after trauma or stroke when glucose levels are even acutely elevated [66, 67]. Acute hyperglycemia with a serum glucose level of ≥170 mg/dL is associated with poor outcome in head trauma patients who present with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 8 or lower [68].

Elevated serum glucose can occur in mild concussive head trauma in humans [69] and in mild, moderate, and severe head trauma in rats [70]. Moreover, extracellular glucose is significantly increased in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex ipsilateral to the site of fluid-percussion injury in the rat [71].

Acute onset of hyperglycemia (within 1 hour of injury) contributes to cerebral neuropathology [72]. The presence of even mild-to-moderate serum glucose elevation (≥150 mg/dL) is detrimental to vulnerable brain regions [73], such as the cerebral cortex and hippocampus [74, 75]. These regions mediate self-regulation, emotion, social functioning, and working memory, all cognitive functions adversely affected by TBI [76]. Neurons and astrocytes are both susceptible to hyperglycemia-induced injury [77, 78].

5. β-Defensins Are Mediators of the Innate Immune Response and Modulate Inflammation

The defensin family of immunomodulatory peptides is an evolutionarily conserved group of cationic peptides that contribute to innate host defense. Constitutively expressed hBD-1 and inducible hBD-2 and -3 are expressed by epithelium and epithelial-derived cells [79–83]. All three hBDs can induce cellular expression of cytokines and chemokines; however, hBD-2 and -3 are particularly important mediators of cytokine release, including release of IL-6, MIP-3α, MCP-1, and RANTES through activation of the G protein and phospholipase C-dependent pathways [84]. These hBDs and LL-37 also promote epithelial cell migration and proliferation, angiogenesis, chemotaxis, and wound repair [84, 85]. Recruitment of specific cells such as immature dendritic cells and memory T cells involves the binding to or modulation of the chemokine receptor CCR6 by hBDs-1, -2, or -3 [86–88]. Some hBDs can also interact with other chemokine receptors, including CCR2 [89] and the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4 [4]. These same receptors are also expressed by the immunocompetent astrocytes and microglia of the human brain [90, 91]. The hBDs-1 and -2 can be expressed by astrocytes and microglia of both human [9] and rat brains [92, 93]. The capacity of resident astrocytes and microglia to express hBD-1 is consistent with our hypothesis that hBDs, through their ability to activate immune cells and modulate cytokine release [84, 94], may function to regulate inflammation within the brain. Tiszlavicz and colleagues have recently demonstrated the expression of hBD-2 mRNA and synthesis of hBD-2 protein in human brain capillary endothelium following in vitro exposure to Chlamydophila pneumoniae [95]. Therefore, the immunoregulatory function of the β-defensins may be established by the microenvironment and stimulus experienced by the cell expressing the peptide. Several lines of evidence support both a pro- and anti-inflammatory role for some antimicrobial peptides. These peptides, including hBD-2, and cathelicidin LL-37 may promote the release of both proinflammatory (IL-6, IL-18) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines and chemokines from epithelial cells as shown by several in vitro studies [84, 96]. Donnarumma et al. [97] also have shown in the human lung cell line A549 that hBD-2 alone or in combination with moxifloxacin can reduce the expression of IL-1β. Overexpression of rat β-defensin-2 (rBD-2) in the lungs of Sprague Dawley rats challenged with P. aeruginosa results in reduction of pulmonary inflammation [98]. If the in vitro findings presented above accurately reflect antimicrobial function in vivo, then a dysregulation of cerebral expression of specific antimicrobial peptides may favor either exacerbation or amelioration of the inflammatory response within the brain depending upon which extracellular conditions predominate. With respect to the β-defensins, we propose that hBD-1 and -2 can contribute to either a pro- or anti-inflammatory modulation of the neuroimmune response with dependence upon the temporal cellular expression of respective cytokines and chemokines. The normal expression profile, and therefore function of specific hBDs, may be compromised when the brain is subjected to mechanical trauma or disease. For example, the level of constitutively expressed hBD-1 is selectively upregulated in differentiating, but not proliferating, keratinocytes [99].

Brain trauma is followed by onset of the acute phase stress response and development of acute hypermetabolism within the brain [100]. With moderate-to-severe TBI, increasing insulin resistance leads to a delayed but chronic hypometabolic state that promotes extracellular hyperglycemia [31]. An in vitro study of human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells by Barnea et al. [101] has shown that increasing intracellular glucose availability increases the expression of hBD-1. However, in rodent models of diabetes mellitus type II, hBD level, including that of hBD-1, was low compared to nondiabetic controls. This apparent discrepancy could be corrected by treatment of animals with insulin [102]. Both diabetes and TBI lead to increased insulin resistance and extracellular hyperglycemia. Insulin is required by astrocytes for proper metabolic function [103, 104]. Therefore, brain regions susceptible to the development of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance might affect the inflammatory state of the involved tissues by modulating expression of AMDs, including β-defensin peptides.

6. β-Defensins Are Expressed in Astrocytes, Microglia, and in Epithelium of the Choroid Plexus

TBI leads to activation of astrocytes and microglia as part of the innate immune response [105]. Astrocytes are strategically sited to provide early defense and modulatory control of cellular events following cerebral insult. The gene chip analysis by Falsig et al. [106] is of particular interest as it shows that a number of genes expressed in murine astrocytes are linked to antiviral/antimicrobial defense and are coordinately regulated. The analysis did not assess either β-defensins or the cathelicidin LL37. Nevertheless, these findings, together with the reported induction of hBD-2 in human astrocytes by cytokines [9], are consistent with the hypothesis that hBD-2 might function as an initial line of defense within the CNS either as an antimicrobial, immunomodulator, or both. Astrocytes, microglia, and the choroid plexus constitutively express hBD-1 [42], again suggesting that hBDs could play a role in the innate immune response of the traumatized brain.

Currently, there are no reported studies on hBD expression or function within the human brain. Hyperglycemia [70], concomitant with increased insulin resistance, is an early feature of TBI in the acute phase response to trauma [107]. It is noteworthy that the level of trauma needs not be severe to elicit a marked elevation in cortical glucose within 24 hours [108], and even mild hyperglycemia can adversely affect brain function [109]. Although hyperglycemia remains a primary focus of many studies, insulin resistance might also contribute significantly to cellular dysfunction following trauma. Insulin receptors are widely distributed within the brain with their highest densities in cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and hippocampus [110]. Because glucose incorporation into astrocytes is insulin sensitive [111], astrocytes could be particularly prone to trauma-induced dysfunction although some signaling pathways associated with hippocampal neurons also are insulin dependent [112, 113]. Acute hyperglycemia and insulin resistance can result in alteration of the immune response in favor of a proinflammatory condition leading to more extensive or prolonged inflammation [64].

7. β-Defensins May Be Neuroprotective through Their Ability to Impede Cellular Apoptosis, Increase Cellular Proliferation, and Promote CNS Wound Healing

Apoptosis contributes to delayed neuronal cell death in TBI [114]. Mild TBI in the lateral fluid percussion rat model has induced apoptotic TUNEL(+) astrocytes and neurons in both grey matter of the cortex and in underlying white matter [115, 116]. There is evidence that β-defensins in vitro can attenuate the onset of proapoptotic mechanisms in human neutrophils where hBD-3 can reduce apoptosis via the chemokine receptor CCR6 [117].

TBI may increase apoptosis and also enhance reactive astrocytosis [118]. Of importance is the observation that ablation of proliferating reactive astrocytes with the antiviral agent ganciclovir significantly increases neuronal degeneration and the inflammatory state [119]. Studies in vivo indicate that chronic activation of the innate immune response can induce neuronal injury [120–122], perhaps through activation of the inflammasome complex [123]. Thus, modulation of this response, perhaps by specific hBDs and/or other immunomodulatory antimicrobial peptides, could be critical to the maintenance of neuronal health. Moreover, the potential contribution of β-defensins to reparation of inflammation-induced cellular injury in the CNS is illustrated by the ability of hBD-2 to stimulate proangiogenic activity, as demonstrated in human umbilical vein endothelial cells despite absence of growth factors such as VEGF [23]. These observations in vitro, although limited to conditions and to cells not directly related to those within the CNS, are nevertheless consistent with a proposed function for hBD-2 within the brain that is supported by the inducible expression of this peptide in human astrocytes stimulated by the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α [9].

8. Dendritic Cells Are Critical Modulators of the Innate and Adaptive Immune Response

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (APCs) crucial to pathogen recognition and regulation of the inflammatory response. DCs are critical to the induction and regulation of adaptive immunity through their release of cytokines, and subsequent activation of lymphocytes, polarization of T-helper type 1 (Th1) CD4+ cells, development of cytolytic T cells, and expansion of the antibody response to antigen [124, 125]. Upregulation of toll-like receptors (TLRs) by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) can induce maturation of DC to an inflammatory phenotype that upregulates the adaptive immune response [126]. Under physiological conditions, dendritic cells are restricted to the meninges and choroid plexus of the brain and are not normally present within the brain parenchyma [127]. However, rapid accumulation of DCs proximal to the site of brain inflammation occurs with neurodegeneration [128], including AD [129], autoimmune disease, bacterial and viral infection, and brain trauma [128, 130, 131]. Recent studies suggest that DCs exhibit a regulatory function with regard to the neuroinflammatory process [132] and can express both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [133]. In this regard, maintenance of an active DC population may contribute to prolongation of the inflammatory process [134–136] with progressive neurodegeneration.

9. β-Defensin Peptides May Modulate Both Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses within the Brain through Chemotaxis and Promotion of Dendritic Cell Maturation

The antimicrobial function of AMPs might actually be secondary to their immunomodulatory capabilities [137]. One mechanism by which the initial innate response can activate an adaptive response is through chemoattraction, maturation, and activation of dendritic cells [138]. At least some AMPs, including β-defensins-1, -2, and -3, and LL-37 can chemoattract immature dendritic cells and induce their maturation [139–142]. Yang et al. [86] have shown that human β-defensin-2 is chemotactic for immature DCs through binding to the DC-expressed CCR6 receptor.

10. β-Defensin Peptides May Limit Inflammation through Anti-Inflammatory Pathways and by Induction of Dendritic Cell Death

The ability of specific β-defensin peptides to regulate inflammation may rely not only on promotion of adaptive immunity and inflammation, but also on curtailing the inflammatory process itself. Chronic inflammation is counterproductive, often contributing to excessive cell death, and compromising tissue repair. Hao et al. [143] have demonstrated improved wound healing in cultured bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal cells (BMSCs) expressing both human platelet-derived growth factor-A (hPDGF-A) and hBD-2. Pingel et al. [144] also show that hBD-3 can attenuate the proinflammatory cytokine response to microbial antigens by myeloid dendritic cells exposed to recombinant hemagglutinin B (rHagB), one of five hemagglutinins that promote binding of Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) to host cells, including myeloid DCs. The mechanism by which hBD-3 attenuates the IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α response in human myeloid dendritic cells was not determined. However, Pingel et al. demonstrated strong binding between the highly cationic hBD-3 and immobilized rHagB. Furthermore, significantly lower levels of ERK 1/2, but not JNK 1/2 or p38, were observed, suggesting a partial involvement of the MAPK pathways, important to control the inflammatory response to P. gingivalis. The authors propose that binding of hBD-3 to rHagB may be an initial step leading to suppression of select proinflammatory cytokine pathways in human myeloid dendritic cells. Recently, Semple et al. [145] demonstrated that hBD-3 attenuates transcription of proinflammatory genes in TLR4-stimulated macrophages. Whether these results are relevant to defensin function within the brain is unknown. Such a functional versatility on the part of specific defensins would be highly advantageous to controlled modulation of the immune response within the CNS.

β-defensins might also modulate the duration of inflammation by controlling the viability of activated macrophages and the same dendritic cells that they chemoattract and induce to maturity. In an interesting study of TLR-4-dependent maturation of immature DCs by murine β-defensin-2 (mBD-2), Biragyn et al. demonstrated that following activation of DCs, mBD-2, not orthologous to any known hBDs, induces DC death via an NFκB-dependent induction of TNF-α and TNF receptor 2 (TNFR2) expression on the APC surface [146]. Cytotoxicity was shown to be due to a defensin-induced signaling cascade that requires TNFR2 and not mBD-2 directly. Additional experiments by this group clearly showed that these observations were not restricted to murine β-defensin, since hBD-3 also was capable of inducing, first, DC maturation and then death several days later.

The studies noted above strongly suggest that at least some hBDs, under certain conditions, possess an anti-inflammatory or inflammation-limiting capability. Conditions under which these defensin-related anti-inflammatory mechanisms are activated in vivo and whether they function within the CNS remain to be determined. The pro- or anti-inflammatory nature of hBDs may depend largely on temporal regulation of cellular events, including number and type of inflammatory cells (microglial activation state) and molecular expression and inactivation of pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by immunocompetent cells within the cellular microenvironment.

11. Summary and Concluding Remarks

A number of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, the aging process, TBI, and type II diabetes mellitus, exhibit similar pathogenic cascades. Hyperglycemia and elevated insulin resistance are common sequalae, among others, that may underlie cellular dysfunction within the brain involving altered expression of immunomodulatory peptides, such as the β-defensins. We propose, based on studies that support a central role for β-defensins as modulators of immune response and inflammation in extracerebral tissues, that these peptides, and perhaps other AMPs endogenous to the human brain, contribute to regulation of the immune response and inflammation within the CNS. This would likely occur in part through the ability of specific antimicrobial peptides, such as β-defensins-1, -2, and -3, to regulate dendritic cell function and viability. We also propose that neuropathological development of hyperglycemia, and/or insulin resistance, attenuates β-defensin function through reduced cellular expression of the peptide and compromised ability to modulate the neuroimmune response, perhaps through uncontrolled dendritic cell activation. However, AMP function is unlikely to be influenced by a single mechanism. Given the complex etiology of neurodegenerative diseases, it is likely that peptide activity is a function of multiple factors inherent within specific regions of the brain. The net effect on AMP function may be reflected in increased pro- or anti-inflammatory activity by the AMP peptide(s) that results in an intensified or prolonged inflammatory process. The recent study by Soscia et al. [147], for example, suggests that the oligomerized form of β-amyloid 1–42 (Aβ), an anionic peptide associated with AD neuropathology, may function as a proinflammatory antimicrobial peptide in regions of the brain exhibiting elevated levels of the peptide. Oligomerization of monomeric hBD-2 also has been demonstrated and is likely to occur with other hBDs and AMPs [148]. Many AMPs exhibit structural characteristics, including a β-sheet conformation similar to Aβ(1–42) that contribute to oligomerization. Yet while some AMPs like frog skin dermaseptin S9 form amyloid-like fibrils [149], others such as hBD-2 and -3 do not [150]. Interestingly, as noted by these studies, amyloidogenic properties may adversely affect normal peptide function and favor a proinflammatory state, while nonamyloidogenic oligomerization appears to promote antimicrobial function, including that of the β-defensins without promoting inflammation. Increased or decreased β-defensin expression and function could contribute significantly to chronic inflammation and ultimately to the neurodegenerative process itself. Clearly, regulation of the innate immune response in tandem with upregulation of cellular repair processes within the CNS is complex and highly integrated with considerable redundancy. Nevertheless, the proposal that AMPs function within the brain is supported by the cytokine-induced expression of AMPs by human astrocytes and microglial and the functional activity of AMPs in multiple organ systems, as described above. Whether specific AMPs play a central role in the onset or promotion of the neuroinflammatory process and neurodegeneration is currently unknown, emphasizing the importance of further investigation into the regulatory mechanisms that control innate and adaptive immunity within the CNS.

Acknowledgment

This paper is dedicated to Mark A. Smith, Ph.D., a visionary scientist who was not afraid to think “outside the box,” and whose passion for science and curiosity will not be forgotten.

References

- 1.Fernández JA, Rojo L, Kuljis RO, Maccioni RB. The damage signals hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2008;14(3):329–333. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maccioni RB, Rojo LE, Fernández JA, Kuljis RO. The role of neuroimmunomodulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1153:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormick TS, Weinberg A. Epithelial cell-derived antimicrobial peptides are multifunctional agents that bridge innate and adaptive immunity. Periodontology 2000. 2010;54(1):195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laube DM, Yim S, Ryan LK, Kisich KO, Diamond G. Antimicrobial peptides in the airway. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2006;306:153–182. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29916-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams WM. Microcirculation: Function, Malfunction and Measurement. Hauppauge, NY, USA: NOVA Science Publishers; 2009. Microvascular function and inflammation in the senescent, neurodegenerative, and traumatized brain; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivest S. Regulation of innate immune responses in the brain. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9(6):429–439. doi: 10.1038/nri2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Watering S, Sterk PJ, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. Defensins: key players or bystanders in infection, injury, and repair in the lung? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1999;104(6):1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auvynet C, Rosenstein Y. Multifunctional host defense peptides: antimicrobial peptides, the small yet big players in innate and adaptive immunity. FEBS Journal. 2009;276(22):6497–6508. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hao H-N, Zhao J, Lotoczky G, Grever WE, Lyman WD. Induction of human β-defensin-2 expression in human astrocytes by lipopolysaccharide and cytokines. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;77(4):1027–1035. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman P, Termén S, Johansson L, et al. The antimicrobial peptide rCRAMP is present in the central nervous system of the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;93(5):1132–1140. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen MØ, Larsen A, Stoltenberg M, Penkowa M. Cell death in the injured brain: roles of metallothioneins. Progress in Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2009;44(1):1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letiembre M, Liu Y, Walter S, et al. Screening of innate immune receptors in neurodegenerative diseases: a similar pattern. Neurobiology of Aging. 2009;30(5):759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparkman NL, Johnson RW. Neuroinflammation associated with aging sensitizes the brain to the effects of infection or stress. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2008;15(4–6):323–330. doi: 10.1159/000156474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beauquis J, Homo-Delarche F, Revsin Y, de Nicola AF, Saravia F. Brain alterations in autoimmune and pharmacological models of diabetes mellitus: focus on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis disturbances. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2008;15(1):61–67. doi: 10.1159/000135625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia HP, Mills JN, Barahmand-Pour F, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of rat genes encoding homologues of human β-defensins. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(9):4827–4833. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4827-4833.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandenburg L-O, Varoga D, Nicolaeva N, et al. Role of glial cells in the functional expression of LL-37/rat cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide in meningitis. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2008;67(11):1041–1054. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31818b4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van den Heuvel C, Thornton E, Vink R. Traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Progress in Brain Research. 2007;161:303–316. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)61021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed Z, Baker D, Cuzner ML. Interleukin-12 induces mild experimental allergic encephalomyelitis following local central nervous system injury in the Lewis rat. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2003;140(1-2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inglese M, Bomsztyk E, Gonen O, Mannon LJ, Grossman RI, Rusinek H. Dilated perivascular spaces: hallmarks of mild traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2005;26(4):719–724. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinoshita K, Chatzipanteli K, Vitarbo E, et al. Interleukin-1β messenger ribonucleic acid and protein levels after fluid-percussion brain injury in rats: importance of injury severity and brain temperature. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(1):195–203. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200207000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Utagawa A, Truettner JS, Dietrich WD, Bramlett HM. Systemic inflammation exacerbates behavioral and histopathological consequences of isolated traumatic brain injury in rats. Experimental Neurology. 2008;211(1):283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitarbo EA, Chatzipanteli K, Kinoshita K, Truettner JS, Alonso OF, Dietrich WD. Tumor necrosis factor α expression and protein levels after fluid percussion injury in rats: the effect of injury severity and brain temperature. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(2):416–424. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000130036.52521.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baroni A, Donnarumma G, Paoletti I, et al. Antimicrobial human β-defensin-2 stimulates migration, proliferation and tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Peptides. 2009;30(2):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahida YR, Cunliffe RN. Defensins and mucosal protection. Novartis Foundation Symposium. 2004;263:71–77. doi: 10.1002/0470090480.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin L, Dale BA. Activation of protective responses in oral epithelial cells by Fusobacterium nucleatum and human β-defensin-2. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2007;56(part 7):976–987. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann KF, Rojo L, Navarrete LP, Farías G, Reyes P, Maccioni RB. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease: molecular links & clinical implications. Current Alzheimer’s Research. 2008;5(5):438–447. doi: 10.2174/156720508785908919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duan W, Guo Z, Jiang H, Ware M, Li XJ, Mattson MP. Dietary restriction normalizes glucose metabolism and BDNF levels, slows disease progression, and increases survival in huntingtin mutant mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(5):2911–2916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roriz-Filho JS, Sa-Roriz TM, Rosset I, et al. (Pre)diabetes, brain aging, and cognition. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1792(5):432–443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang T, Pan BS, Zhao B, Zhang LM, Huang YL, Sun FY. Exacerbation of poststroke dementia by type 2 diabetes is associated with synergistic increases of β-secretase activation and β-amyloid generation in rat brains. Neuroscience. 2009;161(4):1045–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biessels GJ, Staekenborg S, Brunner E, Brayne C, Scheltens P. Risk of dementia in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He ZH, Zhi XG, Sun XC, Tang WY. Correlation analysis of increased blood glucose and insulin resistance after traumatic brain injury in rats. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007;27(3):315–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andresen E, Günther G, Bullwinkel J, Lange C, Heine H. Increased expression of β-defensin 1 (DEFB1) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Hancock RE. Immunomodulatory properties of defensins and cathelicidins. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2006;306:27–66. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29916-5_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Münch G, Schicktanz D, Behme A, et al. Amino acid specificity of glycation and protein-AGE crosslinking reactivities determined with a dipeptide SPOT library. Nature Biotechnology. 1999;17(10):1006–1010. doi: 10.1038/13704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12(7):388–399. doi: 10.1038/nrn3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annual Review of Immunology. 2011;29:415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonard BE. Inflammation, depression and dementia: are they connected? Neurochemical Research. 2007;32(10):1749–1756. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9385-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakabayashi M, Suzaki S, Tomita H. Neural injury and recovery near cortical contusions: a clinical magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2007;106(3):370–377. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bondanelli M, de Marinis L, Ambrosio MR, et al. Occurrence of pituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2004;21(6):685–696. doi: 10.1089/0897715041269713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marklund N, Salci K, Ronquist G, Hillered L. Energy metabolic changes in the early post-injury period following traumatic brain injury in rats. Neurochemical Research. 2006;31(8):1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park E, McKnight S, Ai J, Baker AJ. Purkinje cell vulnerability to mild and severe forebrain head trauma. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2006;65(3):226–234. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000202888.29705.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakayama K, Okamura N, Arai H, Sekizawa K, Sasaki H. Expression of human β-defensin-1 in the choroid plexus. Annals of Neurology. 1999;45(5):p. 685. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199905)45:5<685::aid-ana25>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phulwani NK, Kielian T. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) 1–3 regulate astrocyte activation. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008;106(2):578–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kipp M, Norkute A, Johann S, et al. Brain-region-specific astroglial responses in vitro after LPS exposure. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2008;35(2):235–243. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurley C, Nichols J, Liu S, Phulwani NK, Esen N, Kielian T. Microglia and astrocyte activation by toll-like receptor ligands: modulation by PPAR-γ agonists. PPAR Research. 2008;2008:15 pages. doi: 10.1155/2008/453120. Article ID 453120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walter L, Neumann H. Role of microglia in neuronal degeneration and regeneration. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2009;31(4):513–525. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farina C, Aloisi F, Meinl E. Astrocytes are active players in cerebral innate immunity. Trends in Immunology. 2007;28(3):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hailer NP. Immunosuppression after traumatic or ischemic CNS damage: it is neuroprotective and illuminates the role of microglial cells. Progress in Neurobiology. 2008;84(3):211–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffman WH, Casanova MF, Cudrici CD, et al. Neuroinflammatory response of the choroid plexus epithelium in fatal diabetic ketoacidosis. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2007;83(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laird MD, Vender JR, Dhandapani KM. Opposing roles for reactive astrocytes following traumatic brain injury. NeuroSignals. 2008;16(2-3):154–164. doi: 10.1159/000111560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boddie DE, Currie DG, Eremin O, Heys SD. Immune suppression and isolated severe head injury: a significant clinical problem. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2003;17(5):405–417. doi: 10.1080/02688690310001611198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schiepers OJ, Wichers MC, Maes M. Cytokines and major depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2005;29(2):201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van West D, Maes M. Activation of the inflammatory response system: a new look at the etiopathogenesis of major depression. Neuroendocrinology Letters. 1999;20(1-2):11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeong HJ, Hong S-H, Nam Y-C, et al. The effect of acupuncture on proinflammatory cytokine production in patients with chronic headache: a preliminary report. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2003;31(6):945–954. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X03001661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lenzlinger PM, Hans VHJ, Joller-Jemelka HI, Trentz O, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Kossmann T. Markers for cell-mediated immune response are elevated in cerebrospinal fluid and serum after severe traumatic brain injury in humans. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2001;18(5):479–490. doi: 10.1089/089771501300227288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adam R, Rüssing D, Adams O, et al. Role of human brain microvascular endothelial cells during central nervous system infection. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2005;94(2):341–346. doi: 10.1160/TH05-01-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morganti-Kossmann MC, Satgunaseelan L, Bye N, Kossmann T. Modulation of immune response by head injury. Injury. 2007;38(12):1392–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalla R, Liu Z, Xu S, et al. Microglia and the early phase of immune surveillance in the axotomized facial motor nucleus: impaired microglial activation and lymphocyte recruitment but no effect on neuronal survival or axonal regeneration in macrophage-colony stimulating factor-deficient mice. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;436(2):182–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morganti-Kossmann MC, Rancan M, Otto VI, Stahel PF, Kossmann T. Role of cerebral inflammation after traumatic brain injury: a revisited concept. Shock. 2001;16(3):165–177. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kamm K, Vanderkolk W, Lawrence C, Jonker M, Davis AT. The effect of traumatic brain injury upon the concentration and expression of interleukin-1β and interleukin-10 in the rat. The Journal of Trauma. 2006;60(1):152–157. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196345.81169.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rasley A, Tranguch SL, Rati DM, Marriott I. Murine glia express the immunosuppressive cytokine, interleukin-10, following exposure to Borrelia burgdorferi or Neisseria meningitidis. Glia. 2006;53(6):583–592. doi: 10.1002/glia.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamada H, Yu F, Nito C, Chan PH. Influence of hyperglycemia on oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats: relation to blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Stroke. 2007;38(3):1044–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258041.75739.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Israelsson C, Bengtsson H, Kylberg A, et al. Distinct cellular patterns of upregulated chemokine expression supporting a prominent inflammatory role in traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2008;25(8):959–974. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Knieriem M, Otto CM, Macintire D. Hyperglycemia in critically ill patients. Compendium: Continuing Education For Veterinarians. 2007;29(6):360–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Young B, Ott L, Dempsey R, Haack D, Tibbs P. Relationship between admission hyperglycemia and neurologic outcome of severely brain-injured patients. Annals of Surgery. 1989;210(4):466–472. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198910000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cochran A, Scaife ER, Hansen KW, Downey EC. Hyperglycemia and outcomes from pediatric traumatic brain injury. Journal of Trauma. 2003;55(6):1035–1038. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000031175.96507.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prakash A, Matta BF. Hyperglycaemia and neurological injury. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2008;21(5):565–569. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32830f44e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeremitsky E, Omert LA, Dunham CM, Wilberger J, Rodriguez A. The impact of hyperglycemia on patients with severe brain injury. Journal of Trauma—Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 2005;58(1):47–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000135158.42242.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lazar L, Erez I, Gutermacher M, Katz S. Brain concussion produces transient hypokalemia in children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1997;32(1):88–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dixon CE, Lyeth BG, Povlishock JT. A fluid percussion model of experimental brain injury in the rat. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1987;67(1):110–119. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.1.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Otori T, Friedland JC, Sinson G, McIntosh TK, Raghupathi R, Welsh FA. Traumatic brain injury elevates glycogen and induces tolerance to ischemia in rat brain. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2004;21(6):707–718. doi: 10.1089/0897715041269623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sperry JL, Frankel HL, Vanek SL, et al. Early hyperglycemia predicts multiple organ failure and mortality but not infection. The Journal of Trauma. 2007;63(3):487–493. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31812e51fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laird AM, Miller PR, Kilgo PD, Meredith JW, Chang MC. Relationship of early hyperglycemia to mortality in trauma patients. The Journal of Trauma. 2004;56(5):1058–1062. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000123267.39011.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Avants B, Duda JT, Kim J, et al. Multivariate analysis of structural and diffusion imaging in traumatic brain injury. Academic Radiology. 2008;15(11):1360–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Viant MR, Lyeth BG, Miller MG, Berman RF. An NMR metabolomic investigation of early metabolic disturbances following traumatic brain injury in a mammalian model. NMR in Biomedicine. 2005;18(8):507–516. doi: 10.1002/nbm.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levine B, Fujiwara E, O’Connor C, et al. In vivo characterization of traumatic brain injury neuropathology with structural and functional neuroimaging. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2006;23(10):1396–1411. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kagansky N, Levy S, Knobler H. The role of hyperglycemia in acute stroke. Archives of Neurology. 2001;58(8):1209–1212. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.8.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lin B, Ginsberg MD, Busto R. Hyperglycemic exacerbation of neuronal damage following forebrain ischemia: microglial, astrocytic and endothelial alterations. Acta Neuropathologica. 1998;96(6):610–620. doi: 10.1007/s004010050942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Valore EV, Park CH, Quayle AJ, Wiles KR, McCray PB, Jr, Ganz T. Human β-defensin-1: an antimicrobial peptide of urogenital tissues. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101(8):1633–1642. doi: 10.1172/JCI1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harder J, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. A peptide antibiotic from human skin. Nature. 1997;387(6636):p. 861. doi: 10.1038/43088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harder J, Meyer-Hoffert U, Teran LM, et al. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa, TNF-α, and IL-1β, but not IL-6, induce human β-defensin-2 in respiratory epithelia. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2000;22(6):714–721. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.6.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mathews M, Jia HP, Guthmiller JM, et al. Production of β-defensin antimicrobial peptides by the oral mucosa and salivary glands. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(6):2740–2745. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2740-2745.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao C, Wang I, Lehrer RI. Widespread expression of β-defensin hBD-1 in human secretory glands and epithelial cells. FEBS Letters. 1996;396(2-3):319–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Nakano N, et al. Antimicrobial peptides human β-defensins stimulate epidermal keratinocyte migration, proliferation and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2007;127(3):594–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McDermott AM. The role of antimicrobial peptides at the ocular surface. Ophthalmic Research. 2009;41(2):60–75. doi: 10.1159/000187622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang D, Chertov O, Bykovskaia SN, et al. β-defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286(5439):525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu Z, Hoover DM, Yang D, et al. Engineering disulfide bridges to dissect antimicrobial and chemotactic activities of human β-defensin-3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(15):8880–8885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533186100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hoover DM, Boulègue C, Yang D, et al. The structure of human macrophage inflammatory protein-3α/CCL20. Linking antimicrobial and CC chemokine receptor-6-binding activities with human β-defensins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(40):37647–37654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Röhrl J, Yang D, Oppenheim JJ, Hehlgans T. Human β-defensin 2 and 3 and their mouse orthologs induce chemotaxis through interaction with CCR2. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(12):6688–6694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Flynn G, Maru S, Loughlin J, Romero IA, Male D. Regulation of chemokine receptor expression in human microglia and astrocytes. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2003;136(1-2):84–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tanuma N, Sakuma H, Sasaki A, Matsumoto Y. Chemokine expression by astrocytes plays a role in microglia/macrophage activation and subsequent neurodegeneration in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Acta neuropathologica. 2006;112(2):195–204. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Froy O, Hananel A, Chapnik N, Madar Z. Differential effect of insulin treatment on decreased levels of β-defensins and toll-like receptors in diabetic rats. Molecular Immunology. 2007;44(5):796–802. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hiratsuka T, Nakazato M, Date Y, Mukae H, Matsukura S. Nucleotide sequence and expression of rat β-defensin-1: its significance in diabetic rodent models. Nephron. 2001;88(1):65–70. doi: 10.1159/000045961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kohlgraf KG, Pingel LC, Dietrich DE, Brogden KA. Defensins as anti-inflammatory compounds and mucosal adjuvants. Future Microbiology. 2010;5(1):99–113. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tiszlavicz Z, Endrész V, Németh B, et al. Inducible expression of human β-defensin 2 by Chlamydophila pneumoniae in brain capillary endothelial cells. Innate Immunity. 2011;17(5):463–469. doi: 10.1177/1753425910375582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Nagaoka I, Okumura K, Ogawa H. The human β-defensins (-1, -2, -3, -4) and cathelicidin LL-37 induce IL-18 secretion through p38 and ERK MAPK activation in primary human keratinocytes. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(3):1776–1784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Donnarumma G, Paoletti I, Buommino E, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of moxifloxacin and human β-defensin 2 association in human lung epithelial cell line (A549) stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Peptides. 2007;28(12):2286–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shu Q, Shi Z, Zhao ZY, et al. Protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia and sepsis-induced lung injury by overexpression of β-defensin-2 in rats. Shock. 2006;26(4):365–371. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000224722.65929.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frye M, Bargon J, Gropp R. Expression of human β-defensin-1 promotes differentiation of keratinocytes. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2001;79(5-6):275–282. doi: 10.1007/s001090100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kokiko-Cochran ON, Michaels MP, Hamm RJ. Delayed glucose treatment improves cognitive function following fluid-percussion injury. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;436(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barnea M, Madar Z, Froy O. Glucose and insulin are needed for optimal defensin expression in human cell lines. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;367(2):452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Malik AN, Al-Kafaji G. Glucose regulation of β-defensin-1 mRNA in human renal cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;353(2):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Matsuda T, Murata Y, Kawamura N, et al. Selective induction of α 1 isoform of (Na++K+)-ATPase by insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 in cultured rat astrocytes. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1993;307(1):175–182. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ruiz-Albusac JM, Velazquez E, Iglesias J, Jimenez E, Blazquez E. Insulin promotes the hydrolysis of a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol in cultured rat astroglial cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;68(1):10–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68010010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim JV, Dustin ML. Innate response to focal necrotic injury inside the blood-brain barrier. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(8):5269–5277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Falsig J, Porzgen P, Lund S, Schrattenholz A, Leist M. The inflammatory transcriptome of reactive murine astrocytes and implications for their innate immune function. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;96(3):893–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mowery NT, Gunter OL, Guillamondegui O, et al. Stress insulin resistance is a marker for mortality in traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Trauma. 2009;66(1):145–153. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181938c5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Buczek M, Alvarez J, Azhar J, et al. Delayed changes in regional brain energy metabolism following cerebral concussion in rats. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2002;17(3):153–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1019973921217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Groeneveld ABJ, Beishuizen A, Visser FC. Insulin: a wonder drug in the critically ill? Critical Care. 2002;6(2):102–105. doi: 10.1186/cc1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zulian SE, de Boschero MGI, Giusto NM. Insulin action on polyunsaturated phosphatidic acid formation in rat brain: an “in vitro” model with synaptic endings from cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Neurochemical Research. 2009;34(7):1236–1248. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hundal Ø. Major depressive disorder viewed as a dysfunction in astroglial bioenergetics. Medical Hypotheses. 2007;68(2):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wan Q, Xiong ZG, Man HY, et al. Recruitment of functional GABAA receptors to postsynaptic domains by insulin. Nature. 1997;388(6643):686–690. doi: 10.1038/41792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang H, Wang R, Zhao Z, et al. Coexistences of insulin signaling-related proteins and choline acetyltransferase in neurons. Brain Research. 2009;1249:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tehranian R, Rose ME, Vagni V, et al. Disruption of Bax protein prevents neuronal cell death but produces cognitive impairment in mice following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2008;25(7):755–767. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Conti AC, Raghupathi R, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK. Experimental brain injury induces regionally distinct apoptosis during the acute and delayed post-traumatic period. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18(15):5663–5672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Raghupathi R, Conti AC, Graham DI, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury induces apoptotic cell death in the cortex that is preceded by decreases in cellular Bcl-2 immunoreactivity. Neuroscience. 2002;110(4):605–616. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nagaoka I, Niyonsaba F, Tsutsumi-Ishii Y, Tamura H, Hirata M. Evaluation of the effect of human β-defensins on neutrophil apoptosis. International Immunology. 2008;20(4):543–553. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Säljö A, Bao F, Hamberger A, Haglid KG, Hansson HA. Exposure to short-lasting impulse noise causes microglial and astroglial cell activation in the adult rat brain. Pathophysiology. 2001;8(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4680(01)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Myer DJ, Gurkoff GG, Lee SM, Hovda DA, Sofroniew MV. Essential protective roles of reactive astrocytes in traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2006;129(10):2761–2772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Block ML, Hong JS. Microglia and inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration: multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Progress in Neurobiology. 2005;76(2):77–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lucas SM, Rothwell NJ, Gibson RM. The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;147(supplement 1):S232–S240. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Xiong ZQ, Qian W, Suzuki K, McNamara JO. Formation of complement membrane attack complex in mammalian cerebral cortex evokes seizures and neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(3):955–960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00955.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Trendelenburg G. Acute neurodegeneration and the inflammasome: central processor for danger signals and the inflammatory response? Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2008;28(5):867–881. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Steinman RM, Hemmi H. Dendritic cells: translating innate to adaptive immunity. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2006;311:17–58. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449(7161):419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.van Vliet SJ, Dunnen JD, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Innate signaling and regulation of dendritic cell immunity. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2007;19(4):435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.McMahon EJ, Bailey SL, Miller SD. CNS dendritic cells: critical participants in CNS inflammation? Neurochemistry International. 2006;49(2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Iribarren P, Cui Y-H, Le Y, Wang JM. The role of dendritic cells in neurodegenerative diseases. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2002;50(3):187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ciaramella A, Bizzoni F, Salani F, et al. Increased pro-inflammatory response by dendritic cells from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;19(2):559–572. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fischer H-G, Reichmann G. Brain dendritic cells and macrophages/microglia in central nervous system inflammation. Journal of Immunology. 2001;166(4):2717–2726. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Karman J, Ling C, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Dendritic cells in the initiation of immune responses against central nervous system-derived antigens. Immunology Letters. 2004;92(1-2):107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zozulya AL, Ortler S, Lee JE, et al. Intracerebral dendritic cells critically modulate encephalitogenic versus regulatory immune responses in the CNS. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(1):140–152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2199-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Calvo C-F, Amigou E, Desaymard C, Glowinski J. A pro- and an anti-inflammatory cytokine are synthesized in distinct brain macrophage cells during innate activation. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2005;170(1-2):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pashenkov M, Teleshova N, Link H. Inflammation in the central nervous system: the role for dendritic cells. Brain Pathology. 2003;13(1):23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ludewig B, Odermatt B, Landmann S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Dendritic cells induce autoimmune diabetes and maintain disease via de novo formation of local lymphoid tissue. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;188(8):1493–1501. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Mobilizing dendritic cells for tolerance, priming, and chronic inflammation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1999;189(4):611–614. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hancock REW, Sahl HG. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nature Biotechnology. 2006;24(12):1551–1557. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Joffre O, Nolte MA, Sporri R, Sousa CRE. Inflammatory signals in dendritic cell activation and the induction of adaptive immunity. Immunological Reviews. 2009;227(1):234–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hölzl MA, Hofer J, Steinberger P, Pfistershammer K, Zlabinger GJ. Host antimicrobial proteins as endogenous immunomodulators. Immunology Letters. 2008;119(1-2):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yang D, Biragyn A, Kwak LW, Oppenheim JJ. Mammalian defensins in immunity: more than just microbicidal. Trends in Immunology. 2002;23(6):291–296. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Röhrl J, Yang D, Oppenheim JJ, Hehlgans T. Identification and biological characterization of mouse β-defensin 14, the orthologue of human β-defensin 3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(9):5414–5419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Davidson DJ, Currie AJ, Reid GSD, et al. The cationic antimicrobial peptide LL-37 modulates dendritic cell differentiation and dendritic cell-induced T cell polarization. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(2):1146–1156. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hao L, Wang J, Zou Z, et al. Transplantation of BMSCs expressing hPDGF-A/hBD2 promotes wound healing in rats with combined radiation-wound injury. Gene Therapy. 2009;16(1):34–42. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pingel LC, Kohlgraf KG, Hansen CJ, Eastman CG, Dietrich DE, Burnell KK. Human β-defensin 3 binds to hemagglutinin B (rHagB), a non-fimbrial adhesion from Porphyromonas gingivalis, and attenuates a pro-inflammatory cytokine response. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2008;86:643–649. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Semple F, Macpherson H, Webb S, et al. Human β-defensin 3 affects the activity of pro-inflammatory pathways associated with MyD88 and TRIF. European Journal of Immunology. 2011;41(11):3291–3300. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Biragyn A, Coscia M, Nagashima K, Sanford M, Young HA, Olkhanud P. Murine β-defensin 2 promotes TLR-4/MyD88-mediated and NF-κB-dependent atypical death of APCs via activation of TNFR2. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;83(4):998–1008. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Soscia SJ, Kirby JE, Washicosky KJ, et al. The Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid β-protein is an antimicrobial peptide. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009505. Article ID e9505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Hoover DM, Rajashankar KR, Blumenthal R, et al. The structure of human β-defensin-2 shows evidence of higher order oligomerization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(42):32911–32918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Auvynet C, El Amri C, Lacombe C, et al. Structural requirements for antimicrobial versus chemoattractant activities for dermaseptin S9. FEBS Journal. 2008;275(16):4134–4151. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Saravanan R, Bhattacharjya S. Oligomeric structure of a cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide in dodecylphosphocholine micelle determination by NMR spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2011;1808(1):369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]