Abstract

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (AC) is characterised by myocardial fibrofatty tissue infiltration and presents with palpitations, ventricular arrhythmias, syncope and sudden cardiac death. AC is associated with mutations in genes encoding the desmosomal proteins plakophilin-2 (PKP2), desmoplakin (DSP), desmoglein-2 (DSG2), desmocollin-2 (DSC2) and junctional plakoglobin (JUP). In the present study we compared 28 studies (2004–2011) on the prevalence of mutations in desmosomal protein encoding genes in relation to geographic distribution of the study population. In most populations, mutations in PKP2 showed the highest prevalence. Mutation prevalence in DSP, DSG2 and DSC2 varied among the different geographic regions. Mutations in JUP were rarely found, except in Denmark and the Greece/Cyprus region.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Plakophilin-2, Mutation, Desmosome, Prevalence, Geography

Keywords: Medicine & Public Health; Medicine/Public Health, general

Introduction

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (AC), previously known as arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy or dysplasia (ARVC/D), is a myocardial disease usually with autosomal dominant inheritance and an estimated prevalence of 1:2000 to 1:5000 in the Western world [1, 2]. Based on clinical symptomology, the disease affects men more commonly than women (3:1) and usually becomes manifest between the second and the fourth decade of life. In clinical practice, patients with AC generally manifest with ventricular arrhythmias, palpitations, syncope related to physical exertion, and in a late-stage congestive heart failure. Unfortunately, sudden cardiac death during various daily life activities is the first presentation in 7–23 % of affected patients [3]. Histopathologically, the heart of patients with AC shows myocardial cell death and progressive fibrofatty tissue substitution primarily of the right ventricular myocardium, preceding ventricular dilatation.

Cardiac tissue has to withstand high pressures to enable ejection and therefore individual cardiomyocytes are interconnected robustly by desmosomes in the intercalated disks (IDs). IDs, which consist of three multiprotein complexes, i.e. adherens junctions, desmosomes and gap junctions, provide mechanical and electrical coupling between cells, and serve as an anchoring site for ion channels [4, 5]. Loss-of-function mutations in five different desmosomal protein encoding genes, plakophilin-2 (PKP2), desmoplakin (DSP), desmoglein-2 (DSG2), desmocollin-2 (DSC2) and junctional plakoglobin (JUP), have been identified in AC [6]. The prevalence of these mutations might be related to ethnicity, founder mutations or founder populations [7–9] and therefore may be different in geographically distinct populations. For example, as shown by Van der Zwaag et al. [9] 12 index patients carrying the same PKP2 mutation shared the same haplotype, indicative for a common founder. Geographical distribution of the index patients suggested that the mutation originated in the northern part of the Netherlands [9]. In the present study we describe results from literature on the geographical distribution of mutation prevalence of diagnosed AC patients. Our analysis demonstrates that approximately 46 % of AC cases can be correlated with mutations in one or more desmosomal genes. Furthermore, mutations within the PKP2 gene have the strongest prevalence within the AC population. Finally, some large differences between populations of distinct geographical locations exist.

Methods

Search methods and selection criteria

PubMed and the Cochrane Library databases were examined using combinations of the following search terms and abbreviations: arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, prevalence, genetic mutations, mutational analysis, desmosomes, plakophilin-2 (PKP2), desmoplakin (DSP), desmoglein-2 (DSG2), desmocollin-2 (DSC2), and plakoglobin (JUP). We considered only full-length articles in English, published in the 2004–2011 period, which contained a sample size of more than 15 confirmed AC patients, according to the 1994 or 2010 Task Force Criteria (TFC) [10, 11].

Results

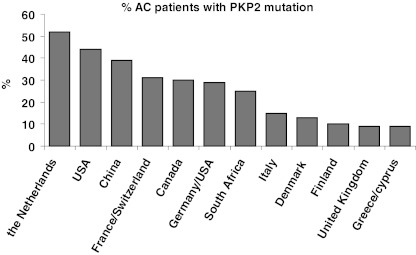

Table 1 summarises the relevant data from 28 studies, ordered according to the country/region from which the study population was derived. In most studies, potential mutations in PKP2 were screened for, and in a subset of the studies (from the Netherlands, USA, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Italy and France/Switzerland), patients were screened for all five desmosomal protein encoding genes. After removing double counted patients, necessary since some larger studies used a subset of previous study populations (e.g. Kapplinger et al.[12]) and some studies searched for additional mutations in patients scoring negative for PKP2 mutation, we observed that of 931 individual patients (probands) screened for, 210 (22.6 %) were found to carry a mutation in PKP2. When prevalence is ordered based on geographical distribution (Fig. 1), relatively most PKP2 mutations were found in the Netherlands, USA and China (39–52 %), while rates below 10 % were found in the UK and Greece/Cyprus.

Table 1.

Number of mutations in five desmosomal genes in genetic studies on AC patients of different geographical regions

| Geographical region Author/year [ref.#) | Total patients | PKP2 (%) | DSP (%) | DSG2 (%) | DSC2 (%) | JUP (%) | Patients with mutation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | |||||||

| Dalal et al/2006 [28] | 58 | 25 (43) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 25 (43) |

| Awad et al/2006 [21] | 33a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (12) | n.d. | n.d. | 4 (12) |

| Yang et al/2006 [29] | 66 | n.d. | 4 (6) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 4 (6) |

| Den Haan et al/2009 [22] | 82 | 37 (45) | 1 (1) | 7 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 43 (52) |

| USA/Netherlands | |||||||

| Kapplinger et al. 2011 [12] | 175 | 88(50) | 2(1) | 16(9) | 4(2) | 1(1) | 102 (58) |

| USA/Canada | |||||||

| Marcus et al/2009 [30] | 100b | 22 (22) | 22 (22) | ||||

| Canada | |||||||

| Barahona-Dussault et al/2010 [23] | 23c | 7 (30) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 3 (13) | 0 (0) | 10 (43) |

| Germany/USA | |||||||

| Gerull et al/2004 [6] | 120 | 32 (27) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 32 (27) |

| Heuser et al/2006 [31] | 88d | 0 (0) | n.d. | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | n.d. | 1 (1) |

| United Kingdom | |||||||

| Syrris et al/2006 [32] | 77e | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) |

| Syrris et al/2006 [33] | 100f | 11 (11) | 0 (0) | n.d. | n.d. | 0 (0) | 11 (11) |

| Sen-Chowdhry et al/2007 [19] | 156 | 10 (6) | 17 (11) | 10 (6) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 39 (25) |

| Sen Chowdhry et al/2007 [24] | 69 | 6 (9) | 7 (10) | 5 (7) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 20 (30) |

| Syrris et al/2007 [34] | 86g | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (10) | n.d. | 0 (0) | 9 (10) |

| the Netherlands | |||||||

| Van Tintelen et al/2006 [35] | 56 | 24 (43) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 24 (43) |

| Bhuiyan et al/2009 [36] | 57 | 23 (40) | n.d. | 5 (9) | 2 (4) | n.d. | 30 (53) |

| Cox et al/2011 [25] | 149 | 78 (52) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 87 (58) |

| Italy/Poland | |||||||

| Basso et al/2006 [37] | 21 | 3 (14) | 3 (14) | 4 (19) | n.d. | n.d. | 10 (48) |

| Italy | |||||||

| Pilichou et al/2006 [20] | 80h | 11 (14) | 13 (16) | 8 (10) | n.d. | n.d. | 32 (40) |

| Bauce et al/2010 [26] | 42 | 7 (17) | 5 (12) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 18 (43) |

| France/Switzerland | |||||||

| Fressart et al/2010 [17] | 135 | 42 (31) | 6 (5) | 14 (10) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 62 (46) |

| Greece/Cyprus | |||||||

| Antoniades et al/2006 [38] | 187 | 16 (9) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 26 (14) | 42 (22) |

| Denmark | |||||||

| Christensen et al/2010 [39] | 53 | 7 (13) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 7 (13) |

| Christensen et al/2010 [27] | 55 | 7 (13) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | 18 (33) |

| Finland | |||||||

| Lahtinen et al/2008/2011 [8, 40] | 29 | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | n.d. | 5 (17) |

| China | |||||||

| Qiu et al/2009 [41] | 18 | 7 (39) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 7 (39) |

| South Africa | |||||||

| Watkins et al/2009 [7] | 36 | 9 (25) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 9 (25) |

aThe population was first tested negative for mutations in PKP2 or DSP and then screened for mutations in DSG2. bOther desmosomal genes were screened for but not reported. cJUP was only tested in patients negative for PKP2, DSP, DSG2 and DSC2 mutations. dDSG2 and DSC2 was only tested in patients negative for PKP2 mutations. eDSC2 was only tested in patients negative for PKP2, DSP, DSG2 and JUP mutations. fPKP2 was only tested in patients negative for DSP and JUP mutations. gDSG2 was only tested in patients negative for PKP2, DSP and JUP mutations. hDSG2 was only tested in patients negative for PKP2 and DSP mutations. n.d., not determined. Studies in bold analysed mutations in all five desmosomal genes and data are displayed graphically in Fig. 2

Fig. 1.

Ranked prevalence of PKP2 mutations associated with AC in different geographical regions

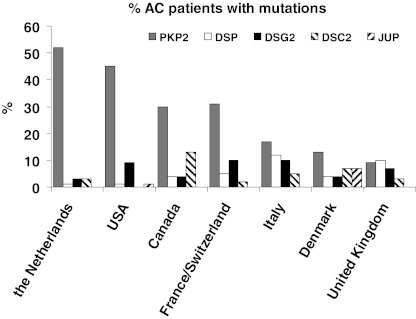

When considering the subset of studies that screened for mutations in all AC associated desmosomal genes, i.e. PKP2, DSP, DSG2, DSC2 and JUP, it was found that 46 % of the AC patients carried a mutation in one or more of these genes. Figure 2 shows the results of mutation prevalence per country/region, again indicating a high prevalence of PKP2 mutations in USA and the Netherlands while, especially in Italy, Denmark and UK, mutations in other desmosomal protein encoding genes are associated more frequently with the AC phenotype. Mutation in the desmosomal gene JUP is associated with AC rarely, with the exception of Denmark and Greece/Cyprus (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of plakophilin-2 (PKP2), desmoplakin (DSP), desmoglein-2 (DSG2), desmocollin-2 (DSC2) and junctional plakoglobin (JUP) mutations in seven geographic regions

Discussion

Our analysis indicates that approximately 46 % of the AC cases can be linked to mutations in genes encoding desmosomal proteins. Mutations in ‘non-desmosomal’ genes coding for transforming growth factor β3 [13] and ryanodine receptor [14], transmembrane protein 43 [15], and the recently identified phospholamban mutation [16] may account in addition for cases of AC. However, the causal effects of transforming growth factor β3 and ryanodine receptor mutations in AC are currently disputed. Screening genes for other structural proteins in the ID, i.e. β-catenin, a-T-catenin and PERP, in a Danish population of 55 confirmed AC patients revealed no mutations [17].

Some regions in our analysis have a large area size (USA, Canada) and/or contain populations from geographically distinct areas (e.g. Germany/USA), although in the latter the USA population is of West-European descent. In other studies, the population was derived from a relatively small region (Padua region, Italy). Therefore, data as presented here may not completely reflect the prevalence of the entire country as regional differences within one country are likely to be found in future. Furthermore, the patient population often included individuals from different origins. For example, Fressart et al. [18] included AC patients from Hispanic, Maghreb and Caribbean origin. Interesting in this respect are the findings of a recent study by Kapplinger et al. [12], where it was shown that in the control population in the absence of heart disease manifestation, DNA variant prevalence in desmosomal protein encoding genes was approximately threefold lower in Caucasians than in non-Caucasians. However, so-called ‘radical mutations’ which are most likely associated with an AC phenotype showed a very low prevalence in both Caucasian (0 %) and non-Caucasian (0.6 %) controls. Finally, radical mutations, defined by the authors as insertions, deletions, splice junction or nonsense mutations, constitute the majority of genetic alterations in so-called mutation-positive AC patients, while many of the missense mutations found in controls and patients most likely have no causal effect with AC [12].

Another complicating factor in comparing different studies is the use of new criteria in the revised TFC to include patients. For example, Sen-Chowdhry et al. [19] included probands with left ventricular or biventricular cardiomyopathy, which may explain the high prevalence of DSP mutations in this study population. However, patients with predominantly left ventricular involvement were often excluded by other authors, due to strict adherence to the TFC defined in 1994 [11]. Previous studies applied different criteria for mutational analysis. For example, Pilichou et al. [20] and Awad et al. [21] sequenced the DSG2 gene only in patients who did not have PKP2 or DSP mutations. In most new studies, all desmosomal protein encoding genes are screened [18, 22–27].

When genetic screening is indicated, all desmosomal protein encoding genes should be included. JUP is only rarely associated with AC, except in Denmark and the Greece/Cyprus region. In the latter region the high incidence of JUP mutations may be due to Naxos disease, a specific condition of AC combined with woolly hair and cutaneous hyperkeratosis.

Acknowledgements

KAJ is a medical student participating in the Honours program of the Faculty of Medicine, UMC Utrecht. This work is financially supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation grant 2007B139 and the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of the Netherlands (ICIN) project # 06901.

Footnotes

Kirolos A. Jacob and Maartje Noorman contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Basso C, Corrado D, Marcus FI, Nava A, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2009;373:1289–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herren T, Gerber PA, Duru F. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: a not so rare ‘disease of the desmosome’ with multiple clinical presentations. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98:141–58. doi: 10.1007/s00392-009-0751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priori SG, Aliot E, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. Task Force on sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1374–450. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noorman M, Heyden MAG, Veen TA, et al. Cardiac cell-cell junctions in health and disease: Electrical versus mechanical coupling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng L, Yung A, Covarrubias M, Radice GL. Cortactin is required for N-cadherin regulation of Kv1.5 channel function. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:20478–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.218560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerull B, Heuser A, Wichter T, et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2004;36:62–1164. doi: 10.1038/ng1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watkins DA, Hendricks N, Shaboodien G, et al. ARVC Registry of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA). Clinical features, survival experience, and profile of plakophylin-2 gene mutations in participants of the arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy registry of South Africa. Hear Rhythm. 2009;6(11 Suppl):S10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahtinen AM, Lehtonen E, Marjamaa A, et al. Population-prevalent desmosomal mutations predisposing to arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Hear Rhythm. 2011;8:1214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwaag PA, Cox MGPJ, Werf C, et al. Recurrent and founder mutations in the Netherlands. Neth Heart J. 2010;18:583–91. doi: 10.1007/s12471-010-0839-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:806–14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenna WJ, Thiene G, Nava A, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Task Force of the Working Group Myocardial and Pericardial Disease of the European Society of Cardiology and of the Scientific Council on Cardiomyopathies of the International Society and Federation of Cardiology. Br Heart J. 1994;71:215–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapplinger JD, Landstrom AP, Salisbury BA, et al. Distinguishing Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia-associated mutations from background genetic noise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2317–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beffagna G, Occhi G, Nava A, et al. Regulatory mutations in transforming growth factor-beta3 gene cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:366–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiso N, Stephan DA, Nava A, et al. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2) Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:189–94. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merner ND, Hodgkinson KA, Haywood AF, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5 is a fully penetrant, lethal arrhythmic disorder caused by a missense mutation in the TMEM43 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:809–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groeneweg JA, Zwaag PA, Werf C, et al. Revised 2010 Task Force Criteria for ARVD/C diagnosis promote inclusion of non-desmosomal mutation carriers. Circulation. 2011;124:A12326. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen AH, Benn M, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Haunso S, Svendsen JH. Screening of three novel candidate genes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;15:267–71. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fressart V, Duthoit G, Donal E, et al. Desmosomal gene analysis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: spectrum of mutations and clinical impact in practice. Europace. 2010;12:861–8. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sen-Chowdhry S, Syrris P, Ward D, Asimaki A, Sevdalis E, McKenna WJ. Clinical and genetic characterization of families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy provides novel insights into patterns of disease expression. Circulation. 2007;115:1710–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilichou K, Nava A, Basso C, et al. Mutations in desmoglein-2 gene are associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113:1171–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awad MM, Dalal D, Cho E, et al. DSG2 mutations contribute to arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:136–42. doi: 10.1086/504393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haan AD, Tan BY, Zikusoka MN, et al. Comprehensive desmosome mutation analysis in North Americans with Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:428–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.858217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barahona-Dussault C, Benito B, Campuzano O, et al. Role of genetic testing in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Clin Genet. 2010;77:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sen-Chowdhry S, Syrris P, McKenna WJ. Role of genetic analysis in the management of patients with Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1813–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox MGPJ, Zwaag PA, Werf C, et al. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy. Pathogenic desmosome mutations in index-patients predict outcome of family screening: Dutch Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy genotype-phenotype follow-up study. Circulation. 2011;123:2690–700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.988287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauce B, Nava A, Beffagna G, et al. Multiple mutations in desmosomal proteins encoding genes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Hear Rhythm. 2010;7:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen AH, Benn M, Bundgaard H, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Haunso S, Svendsen JH. Wide spectrum of desmosomal mutations in Danish patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Med Genet. 2010;47:736–44. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.077891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalal D, Molin LH, Piccini J, et al. Clinical features of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy associated with mutations in plakophilin-2. Circulation. 2006;113:1634–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.568642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Z, Bowles NE, Scherer SE, et al. Desmosomal dysfunction due to mutations in desmoplakin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2006;99:646–55. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000241482.19382.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcus FI, Zareba W, Calkins H, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation: results from the North American Multidisciplinary Study. Hear Rhythm. 2009;6:984–92. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heuser A, Plovie ER, Ellinor PT, et al. Mutant desmocollin-2 causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1081–8. doi: 10.1086/509044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syrris P, Ward D, Evans A, et al. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy associated with mutations in the desmosomal gene desmocollin-2. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:978–84. doi: 10.1086/509122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Syrris P, Ward D, Asimaki A, et al. Clinical expression of plakophilin-2 mutations in familial Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113:356–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syrris P, Ward D, Asimaki A, et al. Desmoglein-2 mutations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: a genotype-phenotype characterization of familial disease. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:581–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tintelen JP, Entius MM, Bhuiyan ZA, et al. Plakophilin-2 mutations are the major determinant of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113:1650–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhuiyan ZA, Jongbloed JD, Smagt J, et al. Desmoglein-2 and desmocollin-2 mutations in Dutch arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomypathy patients: results from a multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:418–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.839829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basso C, Czarnowska E, Della Barbera M, et al. Ultrastructural evidence of intercalated disc remodelling in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: an electron microscopy investigation on endomyocardial biopsies. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1847–54. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antoniades L, Tsatsopoulou A, Anastasakis A, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy caused by deletions in plakophilin-2 and plakoglobin (Naxos disease) in families from Greece and Cyprus: genotype-phenotype relations, diagnostic features and prognosis. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2208–16. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen AH, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Haunso S, Svendsen JH. Missense variants in plakophilin-2 in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy patients–disease-causing or innocent bystanders? Cardiology. 2010;115:148–54. doi: 10.1159/000263456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lahtinen AM, Lehtonen A, Kaartinen M, et al. Plakophilin-2 missense mutations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qiu X, Liu W, Hu D, et al. Mutations of plakophilin-2 in Chinese with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]