Abstract

Small animal models with functional human lymphohematopoietic systems are highly valuable for the study of human immune function under physiological and pathological conditions. Over the last two decades, numerous efforts have been devoted towards the development of such humanized mouse models. This review is focused on human lymphohematopoietic reconstitution and immune function in humanized mice by cotransplantation of human fetal thymic tissue and CD34+ cells. The potential use of these humanized mice in translational biomedical research is also discussed.

Keywords: humanized mouse, hematopoiesis, immune system, immunodeficient mouse, thymopoiesis

Introduction

The need for humanized mouse models is largely driven by the fact that many findings from conventional animal models do not apply to humans due to the intrinsic differences between species. Humanized mice with functional human hematopoietic and lymphoid systems are particularly useful in the study of pathogens and therapies that specifically target human lymphohematopoietic cells. Over the last two decades, a number of humanized mouse models have been created for the study of human immune responses in vivo.1 Among these models, two are particularly worth mentioning. One is created by injecting human CD34+ cord blood cells into newborn immunodeficient mice.2, 3 Although transplantation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells has been inefficient in achieving human T cell development in adult mice,4, 5 human thymopoiesis and T-cell development in the recipient mouse thymus can be achieved by transplantation of human CD34+ cells into newborn immunodeficient mice.2, 3 However, the thymus in these mice remained small with a cellularity of approximately 3×105, which is less than 1% of an immunocompetent mouse thymus, indicating inefficient human thymopoiesis in the mouse thymus.2 Furthermore, although such humanized mice can mount in vivo immune responses to viral infections (e.g., Epstein–Barr virus),2 there is emerging evidence indicating the failure of these mice to develop efficient antigen-specific immune responses.6, 7, 8, 9 Furthermore, these mice were unable to produce T cell-dependent antibodies after immunization with antigens.9, 10 This is likely due to a lack of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-restricted antigen recognition by human T cells, as improved antigen-specific human T-cell and antibody responses were achieved by CD34+ cell transplantation in transgenic mice expressing HLA molecules.6, 7, 8, 10 The thymus is also important for determining the major histocompatiblity complex restriction of human regulatory T cells (Tregs).11 Moreover, thymic stromal lymphopoietin expressed by thymic epithelial cells within the Hassall corpuscles are essential for the development of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs in the human thymus.12 Thus, although CD4+Foxp3+ cells are detectable in newborn mice receiving CD34+ cells,13 further studies are needed to assess the function of human Tregs in these mice, as hematopoietic cells do not express thymic stromal lymphopoietin14 and human cells do not react to mouse thymic stromal lymphopoietin.15 The other humanized mouse model is created by cotransplantation of human fetal thymic tissue and CD34+ cells, which is discussed and illustrated in this review.

Human lymphohematopoietic cell reconstitution in immunodeficient mice receiving cotransplantation of human fetal thymic tissue and CD34+ cells

The first humanized mouse model with durable human thymopoiesis and T-cell development was established by implanting human fetal thymic (Thy)/liver (Liv) tissues under the renal capsule in CB17-scid mice by McCune and colleagues,16 after they confirmed the potential of human fetal thymic tissue to grow in these mice.17, 18 The surviving Thy/Liv graft was found to be similar to that of normal human bone marrow, and to contain hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)/progenitors that are capable of forming colonies of myelomonocytic and erythroid lineages in vitro.16 Improved human thymopoiesis and T-cell development were later achieved by implantation of human fetal Thy/Liv tissues into NOD/SCID mice19, 20 that have significantly reduced natural killer (NK) cell activity and less mature macrophages.21, 22, 23 However, in general, the human Thy/Liv-grafted mice showed poor reconstitution with human B and myeloid cells.20 Furthermore, these humanized mice failed to develop efficient in vivo immune responses.19, 20 Since bone marrow-derived antigen presenting cells (APCs) play an important role in the induction of antigen-specific T-cell responses,24, 25, 26 the lack of reconstitution with non-T cell human lineages (e.g., APCs)20 may be responsible for the insufficient in vivo immune responses of human T cells in human Thy/Liv-grafted mice.

One strategy that was used to improve reconstitution with non-T-cell lineage human hematopoietic cells was intravenous injection of human hematopoietic stem cells into human Thy/Liv tissue-grafted mice. Since injection of ficolled human fetal liver mononuclear cells failed to achieve sustained human T-cell reconstitution,17 purified human CD34+ cells were used.19, 20 Cotransplantation of human Thy/Liv (under the renal capsule) and CD34+ fetal liver cells (i.v.) significantly improved both reconstitution with human B cells and myeloid (including Lin−CD11c+HLA-II+ myeloid and Lin−CD123+HLA-II+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells) cells, and T-cell development in NOD/SCID mice.19, 20 Almost all major human T-cell subsets, including CD4, CD8, Treg and invariant natural killer T (NKT) cells, were detected in these mice. Human CD4 and CD8 T cells expressing HIV coreceptors, CXC chemokine receptor type 4 and CC chemokine receptor type 5, were also detected in the spleen and intestine of these humanized mice (Habiro K and Yang YG, unpubl. data, 2006), suggesting the suitability of these mice for the study of HIV pathogenesis. Furthermore, the humanized Thy/HSC mice showed significant repopulation with human γδTCR+ intraepithelial T lymphocytes, mostly CD4−CD8αα+ and CD4−CD8−, in the intestine (Habiro K and Yang YG, unpubl. data, 2007; Figure 1). The spleen from these humanized mice showed formation of white pulp, and a follicular structure was observed throughout the organ.20, 27 Similar results were also observed in subsequent studies from other groups, and such human Thy/Liv/CD34+ cell-grafted mice were later called bone marrow–liver–thymus mice.28, 29 We recently demonstrated that implantation of human fetal liver tissue is unnecessary, and humanized mice with functional human lymphohematopoietic systems can be achieved by transplantation of fetal thymic tissue (under the renal capsule) and CD34+ cells (i.v.) (Figure 2). Similar to Thy/Liv/CD34+ cell-grafted mice, human thymic grafts in these mice underwent significant growth (with a cellularity of >2×108) and maintained a normal phenotypic distribution of human thymocyte subsets. Therefore, for the sake of simplicity, hereafter we refer to both Thy/Liv/CD34+ cell- and Thy/CD34+ cell-grafted mice as humanized Thy/HSC mice. Omission of liver tissue implantation makes intravenous injection of CD34+ cells the only stem cell source for T-cell development, which thereby improves the ratio of transgene-expressing T cells (e.g., transgenic TCR) in humanized mice receiving genetically manipulated CD34+ cells. The IL-2 receptor γ-chain (also known as common γ-chain) is an important component of the receptor complex for several interleukins including IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21, which are crucial for the development of T, B and NK cells.30 Because of the complete NK cell deficiency in NOD/SCID/γc−/− (NSG) mice, humanized Thy/HSC NSG mice showed significantly faster reconstitution with human hematopoietic cells than humanized Thy/HSC NOD/SCID mice.

Figure 1.

Repopulation with human γδTCR+ T cells in humanized Thy/HSC mice. Flow cytometric profiles of intestine intraepithelial T cells from a representative Thy/HSC mouse are shown. Human γδTCR+ T cells were also detected at lower levels in the spleen. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; Thy, thymic.

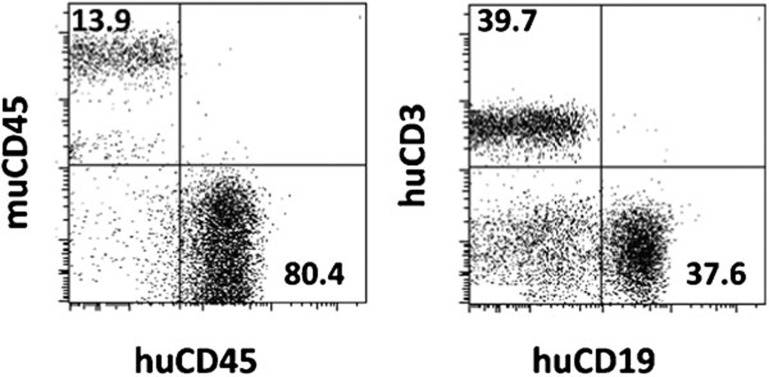

Figure 2.

Human lymphohematopoietic reconstitution in humanized mice receiving human fetal thymic tissue (under the renal capsule) and CD34+ cells (i.v.). Representative flow cytometric profiles depicting human chimerism in PBMCs at week 12 are shown. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

In vivo antigen-specific immune responses of humanized Thy/HSC mice

Xenograft rejection

The immunocompetence and capability of mediating robust in vivo immune responses of humanized Thy/HSC mice was first shown by their ability to spontaneously reject porcine skin xenografts.19, 20 The fact that Thy/HSC mice, but not Thy/Liv mice, were able to spontaneously reject porcine skin grafts, indicates that intravenous injection of CD34+ HSCs is critical for establishing a functional human immune system, presumably by improving reconstitution with human APCs and B cells.20 Injection of human CD34+ HSCs is also important for maintaining long-term immunocompetence because (i) engrafted CD34+ cells are required for sustaining human thymopoiesis and T-cell development and (ii) CD34+ HSC-derived APCs are essential for survival and homeostatic proliferation of human T cells in the periphery.31 Further studies have demonstrated that Thy/HSC mice are also capable of rejecting porcine islet32 and thymic xenografts.33 Humanized Thy/HSC mice with an established human immune system provide a useful and thus far only model for assessing in vivo responses and tolerance of the human immune system to porcine xenoantigens.20, 33

Anti-viral immunity

Humanized mice with a functional immune system are a valuable model for studying human-tropic viral infections, such as HIV and Epstein–Barr virus. Although humanized mice with viral-target human cells (e.g., human T cells for HIV) permit analysis of viral infections, the assessment of antiviral immunity and vaccine therapies requires humanized mice with a functional human immune system. Studies by Melkus and colleagues demonstrated the ability of Thy/HSC mice to develop robust HLA class I- and class II-restricted adaptive immune responses to Epstein–Barr virus infection.28 Humanized Thy/HSC mice were also found to develop robust HIV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell and antibody responses following HIV infection.34 These studies demonstrate the utility of this humanized mouse model for the study of antiviral immunotherapies.

B-cell function and antibody production

The presence of high levels of human IgM and IgG antibodies in the sera of humanized Thy/HSC mice19 indicates that human B cells developing in these mice are functional. A more detailed analysis of human B-cell function and T–B cell interaction was performed in humanized Thy/HSC mice after in vivo immunization with T-dependent antigen, 2,4-dinitrophenyl hapten-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (DNP23-KLH).27 The immunized, but not control, humanized mice showed strong antigen-specific T-cell responses and T cell-dependent production of dinitrophenyl-specific human IgG (including IgG1, IgG2 and IgG3) antibodies. These results demonstrated functional human T–B cell interactions resulting in B-cell activation, antibody production and class switching in these humanized mice. The development of functional human B cells in these mice was further shown by the production of anti-pig xenoreactive antibodies following porcine xenotransplantation. Previous studies have shown that porcine islet xenograft rejection in humanized Thy/HSC mice was associated with significant intragraft deposition of human IgM and IgG antibodies.32 Humanized Thy/HSC mice were also found to produce natural and induced cytolytic antibodies against pigs.33

Treg development and function

The development of phenotypically and functionally normal human Tregs was also demonstrated in Thy/HSC mice.35, 36 High frequencies of Foxp3+ Tregs was detected in CD4+CD8−CD25+CD127− thymocytes. Most of these cells were natural Tregs as shown by the expression of Helios,35 a transcription factor that distinguishes natural Tregs from induced Tregs in humans and mice.37, 38 Most thymic natural Tregs in the Thy/HSC mice were CD45RO+CD45RA−, similar to those in the fetal thymus.35, 36 Human CD4+CD25+CD127−Foxp3+ Tregs were also detected in the blood, spleen and lymph nodes of Thy/HSC mice. Importantly, human CD4+CD25+CD127− cells from Thy/HSC mice were capable of suppressing the proliferative response of responder T cells to CD3/CD28 or allogeneic stimulation, and their suppressive ability was comparable to that of Tregs isolated from adult human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).36, 39 These results demonstrate the utility of humanized Thy/HSC mice for the study of human Tregs, including their development and function under physiological and disease settings.

Invariant NKT (iNKT) cell development and function

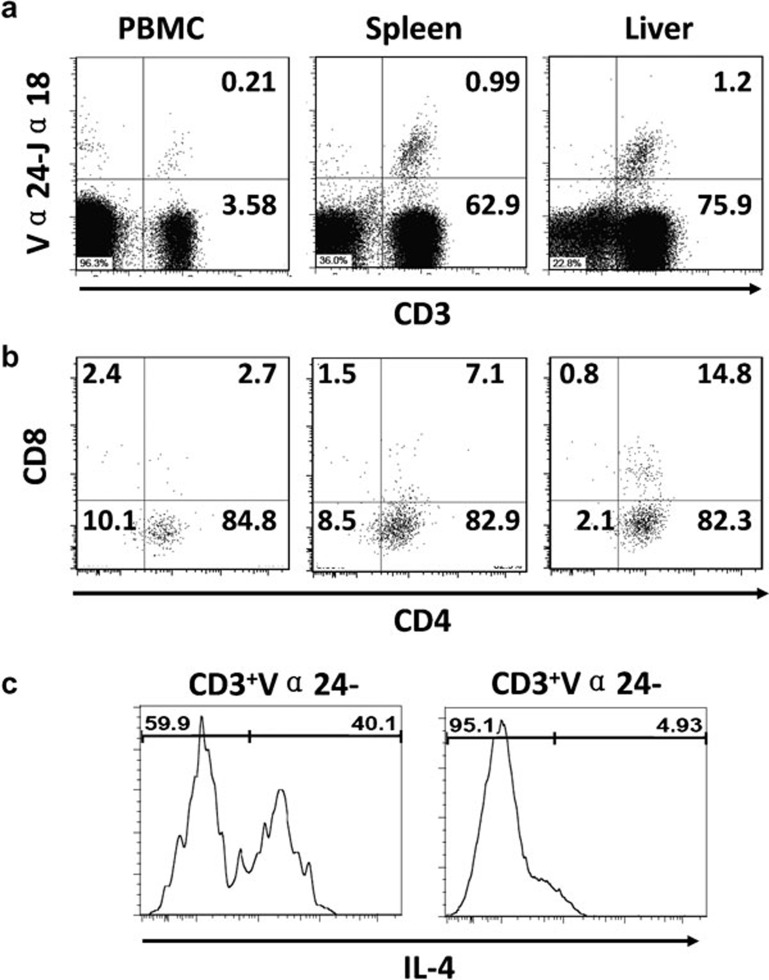

iNKT cells are a rare cell population that develops in the thymus and recognizes glycolipid antigens presented by non-polymorphic CD1d molecules.40 iNKT cells produce large amounts of interferon-γ and IL-4 upon activation,40 and iNKT cell defects have been found to be associated with increased susceptibility to autoimmune diseases and cancers.41, 42 Studies from our group and others43 have shown the development of functional human iNKT cells in humanized Thy/HSC mice. Flow cytometric analysis using anti-human Vα24-Jα18 and α-galactosylceramide-loaded CD1d tetramer revealed that human iNKT cells were present in PBMCs, spleen, liver, bone marrow and thymus from Thy/HSC mice (Figure 3a),43 and that the majority of these cells were CD4+ (Figure 3b). Human iNKT cells developing in these mice were functional as shown by production of interferon-γ and IL-4 after stimulation by α-galactosylceramide43 (Figure 3c). Thus, these humanized mice provide a useful in vivo model for the study of human iNKT cell development and function.

Figure 3.

Human iNKT cell reconstitution in humanized Thy/HSC mice. (a) CD3+Vα24-Jα18+ iNKT cells in various tissues from a humanized Thy/HSC mouse. (b) CD4 and CD8 expression on iNKT cells. (c) IL-4 production by iNKT cells from humanized Thy/HSC mice immunized with α-galactosylceramide (i.v.). HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; iNKT, invariant natural killer T; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; Thy, thymic.

The limitations impeding human hematopoietic reconstitution in immunodeficient mice

Although immunodeficient mice permit engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells and blood cell differentiation, it has yet been able to achieve completely normal human hematopoiesis in any of the currently available immunodeficient mouse strains. Current strategies towards achieving this goal are broadly divided into the following two main categories.

Cytokine environment

One of the major strategies for improving human hematopoiesis in immunodeficient mice is to optimize the recipient hematopoietic cytokine environment. Previous endeavors were focused on cytokines, which are essential to hematopoiesis and blood cell development, but have no or poor cross-reactivity between human and mice. For example, IL-15 is important for NK cell development,44 as are GM-colony-stimulating factor (CSF) and IL-4 for dendritic cells,45 M-CSF for monocytes/macrophages46 and IL-3 for myeloid and erythroid cells.47, 48 However, human cells do not respond to murine IL-15,49 GM-CSF,50 IL-4,51 G-CSF52 or IL-3.53 Accordingly, treatment with human IL-15–IL-15Rα complexes (IL-15 coupled to IL-15Rα)54 or enforced expression of human IL-15 by hydrodynamic injection of human IL-15 plasmids55 were found to be effective in promoting human NK cell development and function in humanized mice. Similarly, enforced expression of human GM-CSF and IL-4 in humanized mice improved reconstitution with human dendritic cells and monocytes/macrophages.55 Recent efforts have explored the use of human cytokine knock-in mice for improving human lymphohematopoietic reconstitution.56 In these mice, human cytokine expression was achieved by knock-in replacement of the mouse counterpart cytokine gene to maintain its promoter and regulatory elements. Human IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in mice receiving human CD34+ cells showed improved human myeloid cell reconstitution in the lung, and functional mucosal immune responses to lung pathogens.57 Improved human myeloid cell differentiation and function were also seen in human CSF-158 and thrombopoietin59 knock-in mice receiving intrahepatic injection of human CD34+ cells at newborn age. The use of immunodeficient mice with knock-in expression of multiple human cytokines should allow for creating humanized mice with better human hematopoiesis and lymphohematopoietic reconstitution.

Macrophage-mediated xenorejection

It has been noted that human red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets are almost undetectable in human CD34+ cell-grafted immunodeficient mice, including NSG mice that have no T, B or NK cells.29 Although enforced expression of human erythropoietin and IL-3 was found to improve human RBC reconstitution in NSG mice receiving human CD34+ cells, the level of human RBCs in these animals remained extremely low compared to the levels of human PBMCs,55 suggesting that the lack of human RBCs in humanized mice likely resulted from poor survival or xenorejection. Recently, we investigated the possibility of xenoimmune rejection of human RBCs by macrophages in NOD/SCID and NSG mice. Both in vitro and in vivo analyses demonstrated the high susceptibility of human RBCs to rejection by mouse macrophages.60 Human RBCs from healthy volunteers were rapidly rejected after transfusion into control, but not macrophage-depleted, mice, and macrophage depletion led to recovery of human RBCs in all humanized mice. Previous studies have shown that the inability of donor CD47 to functionally interact with recipient SIRPα poses a barrier to xenogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation by triggering macrophage-mediated rejection.61, 62, 63 However, the CD47–SIRPα pathway seems unlikely to induce rejection of human RBCs in NOD/SCID or NSG mice, as human CD47 has been shown to cross react with NOD SIRPα.64 In support of this possibility, rejection of human RBCs in immunodeficient mice on the NOD background was found to be significantly more rapid than the rejection of CD47-deficient mouse RBCs.60 Macrophage-mediated xenorejection was even more clearly evidenced in the study assessing human platelet reconstitution in humanized mice. Macrophage depletion resulted in full recovery of human platelet reconstitution (i.e., to a similar level as human PBMCs) that would be otherwise extremely low (∼1%) in blood circulation in humanized Thy/HSC mice or those receiving CD34+ cells along (Hu Z and Yang YG, manuscript submitted). This may explain why human platelet reconstitution was not improved in human CD34+ cell-grafted mice with knock-in expression of human thrombopoietin.59

Concluding remarks

Humanized Thy/HSC mice provide a mouse model that allows human T-cell development in a human thymus and effective human T cell–APC interaction in the periphery. In this model, cotransplantation of human fetal thymic tissue and CD34+ HSCs results in a highly functional human immune system with multilineage repopulation of human lymphohematopoietic cells, effective class-switched antibody responses, T-cell responses to viral infections, and spontaneous allogeneic and xenogeneic graft rejection. The humanized Thy/HSC mouse model is considered a valuable model system for the study of human immune function in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Goda Choi for critical reading of the manuscript. We apologize to those investigators whose work could not be cited as a result of space limitations. The work from the authors' laboratory discussed in this review was supported by grants from NIH (RC1 HL100117, R01 AI064569, PO1 CA111519 and PO1 AI045897) and JDRF (1-2005-72).

References

- Shultz LD, Ishikawa F, Greiner DL. Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:118–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traggiai E, Chicha L, Mazzucchelli L, Bronz L, Piffaretti JC, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Development of a human adaptive immune system in cord blood cell-transplanted mice. Science. 2004;304:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1093933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa F, Yasukawa M, Lyons B, Yoshida S, Miyamoto T, Yoshimoto G, et al. Development of functional human blood and immune systems in NOD/SCID/IL2 receptor γ chainnull mice. Blood. 2005;106:1565–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, Suzue K, Kawahata M, Hioki K, et al. NOD/SCID/γcnull mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood. 2002;100:3175–3182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, Gott B, Chen X, Chaleff S, et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz LD, Saito Y, Najima Y, Tanaka S, Ochi T, Tomizawa M, et al. Generation of functional human T-cell subsets with HLA-restricted immune responses in HLA class I expressing NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull humanized mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13022–13027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000475107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal S, Pearson T, Friberg H, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Rothman AL, et al. Dengue virus infection and virus-specific HLA-A2 restricted immune responses in humanized NOD-scid IL2rγnull mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strowig T, Gurer C, Ploss A, Liu YF, Arrey F, Sashihara J, et al. Priming of protective T cell responses against virus-induced tumors in mice with human immune system components. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1423–1434. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Takahashi T, Okajima A, Shiokawa M, Ishii N, Katano I, et al. The analysis of the functions of human B and T cells in humanized NOD/shi-scid/γcnull (NOG) mice (hu-HSC NOG mice) Int Immunol. 2009;21:843–858. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner R, Chaudhari SN, Rosenberger J, Surls J, Richie TL, Brumeanu TD, et al. Expression of HLA class II molecules in humanized NOD.Rag1KO.IL2RgcKO mice is critical for development and function of human T and B cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi N, Kuniyasu Y, Shimizu J, Otsuka F, et al. Thymus and autoimmunity: production of CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells as a key function of the thymus in maintaining immunologic self-tolerance. J Immunol. 1999;162:5317–5326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Wang YH, Lee HK, Ito T, Wang YH, Cao W, et al. Hassall's corpuscles instruct dendritic cells to induce CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in human thymus. Nature. 2005;436:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/nature03886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Zhang L, Wang R, Jeffrey J, Washburn ML, Brouwer D, et al. FoxP3+CD4+ regulatory T cells play an important role in acute HIV-1 infection in humanized Rag2−/−γC−/− mice in vivo. . Blood. 2008;112:2858–2868. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumelis V, Reche PA, Kanzler H, Yuan W, Edward G, Homey B, et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:673–680. doi: 10.1038/ni805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reche PA, Soumelis V, Gorman DM, Clifford T, Liu M, Travis M, et al. Human thymic stromal lymphopoietin preferentially stimulates myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:336–343. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namikawa R, Weilbaecher KN, Kaneshima H, Yee EJ, McCune JM. Long-term human hematopoiesis in the SCID-hu mouse. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1055–1063. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Shultz LD, Lieberman M, Weissman IL. The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science. 1988;241:1632–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Lieberman M, Weissman IL, McCune JM. Infection of the SCID-hu mouse by HIV-1. Science. 1988;242:1684–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.3201256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan P, Wang L, Diouf B, Eguchi H, Su H, Bronson R, et al. Induction of human T-cell tolerance to porcine xenoantigens through mixed hematopoietic chimerism. Blood. 2004;103:3964–3969. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan P, Tonomura N, Shimizu A, Wang S, Yang YG. Reconstitution of a functional human immune system in immunodeficient mice through combined human fetal thymus/liver and CD34+ cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108:487–492. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz LD, Schweitzer PA, Christianson SW, Gott B, Schweitzer IB, Tennent B, et al. Multiple defects in innate and adaptive immunologic function in NOD/LtSz-scid mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselton RM, Greiner DL, Mordes JP, Rajan TV, Sullivan JL, Shultz LD. High levels of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell engraftment and enhanced susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in NOD/LtSz-scid/scid mice. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:974–982. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflumio F, Izac B, Katz A, Shultz LD, Vainchenker W, Coulombel L. Phenotype and function of human hematopoietic cells engrafting immune-deficient CB17-severe combined immunodeficiency mice and nonobese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency mice after transplantation of human cord blood mononuclear cells. Blood. 1996;88:3731–3740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanova I, Dorfman JR, Germain RN. Self-recognition promotes the foreign antigen sensitivity of naive T lymphocytes. Nature. 2002;420:429–434. doi: 10.1038/nature01146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AD, Kampgen E. Functions of myeloid and lymphoid dendritic cells. Immunol Lett. 2000;72:101–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ. Dendritic cell subsets and lineages, and their functions in innate and adaptive immunity. Cell. 2001;106:259–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonomura N, Habiro K, Shimizu A, Sykes M, Yang YG. Antigen-specific human T-cell responses and T cell-dependent production of human antibodies in a humanized mouse model. Blood. 2008;111:4293–4296. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-121319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkus MW, Estes JD, Padgett-Thomas A, Gatlin J, Denton PW, Othieno FA, et al. Humanized mice mount specific adaptive and innate immune responses to EBV and TSST-1. Nat Med. 2006;12:1316–1322. doi: 10.1038/nm1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz MG, Di Santo JP. Renaissance for mouse models of human hematopoiesis and immunobiology. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1039–1042. doi: 10.1038/ni1009-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugamura K, Asao H, Kondo M, Tanaka N, Ishii N, Ohbo K, et al. The interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain: its role in the multiple cytokine receptor complexes and T cell development in XSCID. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:179–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoe T, Kalscheuer H, Chittenden M, Zhao G, Yang YG, Sykes M. Homeostatic expansion and phenotypic conversion of human T cells depend on peripheral interactions with APCs. J Immunol. 2010;184:6756–6765. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonomura N, Shimizu A, Wang S, Yamada K, Tchipashvili V, Weir GC, et al. Pig islet xenograft rejection in a mouse model with an established human immune system. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habiro K, Sykes M, Yang YG. Induction of human T-cell tolerance to pig xenoantigens via thymus transplantation in mice with an established human immune system. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1324–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DM, Seung E, Frahm N, Cariappa A, Bailey CC, Hart WK, et al. Induction of robust cellular and humoral virus-specific adaptive immune responses in human immunodeficiency virus-infected humanized BLT mice. J Virol. 2009;83:7305–7321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02207-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoe T, Kalscheuer H, Danzl N, Chittenden M, Zhao G, Yang YG, et al. Human natural regulatory T cell development, suppressive function, and postthymic maturation in a humanized mouse model. J Immunol. 2011;187:3895–3903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan K, Zhang B, Zhang W, Zhao Y, Qu Y, Sun C, et al. Efficient peripheral construction of functional human regulatory CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ T cells in NOD/SCID mice grafted with fetal human thymus/liver tissues and CD34+ cells. Transpl Immunol. 2011;25:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClymont SA, Putnam AL, Lee MR, Esensten JH, Liu W, Hulme MA, et al. Plasticity of human regulatory T cells in healthy subjects and patients with type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2011;186:3918–3926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner DL, Hesselton RA, Shultz LD. SCID mouse models of human stem cell engraftment. Stem Cells. 1998;16:166–177. doi: 10.1002/stem.160166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapin L. iNKT cell autoreactivity: what is ‘self' and how is it recognized. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:272–277. doi: 10.1038/nri2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:817–890. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge JL, Chen X, Zhou Y, Rajesh D, Roenneburg DA, Hegde S, et al. Analysis of the CD1 antigen presenting system in humanized SCID mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrozek E, Anderson P, Caligiuri MA. Role of interleukin-15 in the development of human CD56+ natural killer cells from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;87:2632–2640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzwajg M, Canque B, Gluckman JC. Human dendritic cell differentiation pathway from CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cells. Blood. 1996;87:535–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec M, Weglarczyk K, Baran J, Zuba E, Mytar B, Pryjma J, et al. Expansion and differentiation of CD14+CD16− and CD14++CD16+ human monocyte subsets from cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:594–602. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0207117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary AG, Yang YC, Clark SC, Gasson JC, Golde DW, Ogawa M. Recombinant gibbon interleukin 3 supports formation of human multilineage colonies and blast cell colonies in culture: comparison with recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1987;70:1343–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarratana MC, Kobari L, Lapillonne H, Chalmers D, Kiger L, Cynober T, et al. Ex vivo generation of fully mature human red blood cells from hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nbt1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman J, Ahdieh M, Beers C, Brasel K, Kennedy MK, Le T, et al. Interleukin-15 interactions with interleukin-15 receptor complexes: characterization and species specificity. Cytokine. 2002;20:121–129. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf D. The molecular biology and functions of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors. Blood. 1986;67:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann TR, Yokota T, Kastelein R, Zurawski SM, Arai N, Takebe Y. Species-specificity of T cell stimulating activities of IL 2 and BSF-1 (IL 4): comparison of normal and recombinant, mouse and human IL 2 and BSF-1 (IL 4) J Immunol. 1987;138:1813–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixe P, Praloran V. Macrophage colony-stimulating-factor (M-CSF or CSF-1) and its receptor: structure–function relationships. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1997;8:125–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson LM, Jones DG. Cross-reactivity amongst recombinant haematopoietic cytokines from different species for sheep bone-marrow eosinophils. J Comp Pathol. 1994;111:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(05)80115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington ND, Legrand N, Alves NL, Jaron B, Weijer K, Plet A, et al. IL-15 trans-presentation promotes human NK cell development and differentiation in vivo. . J Exp Med. 2009;206:25–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Khoury M, Chen J. Expression of human cytokines dramatically improves reconstitution of specific human-blood lineage cells in humanized mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21783–21788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912274106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willinger T, Rongvaux A, Strowig T, Manz MG, Flavell RA. Improving human hemato-lymphoid-system mice by cytokine knock-in gene replacement. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willinger T, Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, et al. Human IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in mice support human alveolar macrophage development and human immune responses in the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2390–2395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019682108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam C, Poueymirou WT, Rojas J, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, et al. Efficient differentiation and function of human macrophages in humanized CSF-1 mice. Blood. 2011;118:3119–3128. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongvaux A, Willinger T, Takizawa H, Rathinam C, Auerbach W, Murphy AJ, et al. Human thrombopoietin knockin mice efficiently support human hematopoiesis in vivo. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2378–2383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019524108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Van Rooijen N, Yang YG. Macrophages prevent human red blood cell reconstitution in immunodeficient mice. Blood. 2011;118:5719–5720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, VerHalen J, Madariaga ML, Xiang S, Wang S, Lan P, et al. Attenuation of phagocytosis of xenogeneic cells by manipulating CD47. Blood. 2007;109:836–842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Madariaga ML, Wang S, van Rooijen N, Oldenborg PA, Yang YG. Lack of CD47 on nonhematopoietic cells induces split macrophage tolerance to CD47null cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13744–13749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702881104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Wang H, Tahara H, Liu J, Wang X, Asahara T, et al. Role for CD47–SIRPalpha signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5062–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609661104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka K, Prasolava TK, Wang JC, Mortin-Toth SM, Khalouei S, Gan OI, et al. Polymorphism in Sirpa modulates engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1313–1323. doi: 10.1038/ni1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]