Abstract

Objectives

Given use of uterotonics for postpartum haemorrhage and other obstetric indications, the importance of potent uterotonics is indisputable. This study evaluated access to and potency of injectable uterotonics in Ghana.

Design

Study design involved research assistants simulating clients to purchase oxytocin and ergometrine from different sources. Drug potency was measured via chemical assay by the Ghana Food and Drugs Board.

Setting

The study was conducted in three contrasting districts in Ghana.

Outcome measure

The per cent of active pharmaceutical ingredient was measured to assess the quality of oxytocin and ergometrine.

Results

69 formal points of sale were visited, from which 55 ergometrine ampoules and 46 oxytocin ampoules were purchased. None of the ergometrine ampoules were within British Pharmacopoeia specification for active ingredient, none were expired and one showed 0% active ingredient, suggestive of a counterfeit drug. Among oxytocin ampoules purchased, only 11 (26%) were within British Pharmacopoeia specification for active ingredient and two (4%) were expired. The median percentages of active ingredients were 64% and 50% for oxytocin and ergometrine, respectively.

Conclusions

The quality of injectable uterotonics in three contrasting districts in Ghana is a serious problem. Restrictions regarding the sale of unregistered drugs, and of registered drugs from unlicensed shops, are inadequately enforced. These problems likely exist elsewhere but are not assessed, as postmarketing drug quality surveillance is generally restricted to well-funded disease-specific programmes relying on antiretroviral, antimalarial and antibiotic drugs. Maternal health programmes must adopt and fund the same approach to drug quality as is standard in programmes addressing infectious disease.

Article summary

Article focus

The need for high-quality uterotonic drugs for the prevention and treatment of maternal mortality and morbidity in poor countries is indisputable.

Best practice for long-term storage for all injectable uterotonics is refrigeration, which is a key logistical constraint for scale up of postpartum haemorrhage reduction strategies and is a general challenge for maternity services without consistent electricity.

The objectives of the study were to assess the population's access to uterotonic drugs and to assess the chemical potency of ampoules of oxytocin and ergometrine available to the population.

Key messages

Quality of uterotonics is likely a serious problem in Ghana; 89% of all ampoules tested in this study did not meet the specifications for active ingredient. The low level of active ingredient in these ampoules is not due to old drugs; only 2% of these ampoules had expired.

There is little enforcement of the restriction against chemical shops selling uterotonics or of the sale of unregistered uterotonics in these districts.

Inactive uterotonics are not restricted to the private sector; uterotonics outside specification were purchased from private and public sources. It is also clear that public and private sources procure unregistered uterotonics.

Strengths and limitations of this study

An up-to-date listing of points of sale was compiled specifically for this study; a sample of randomly selected sites was visited, and in two of three districts, the selected points of sale represented all the existing accessible chemical sellers and pharmacies.

The simulated client approach prevents possible bias in the selection of ampoules to be sent for chemical testing.

The number of points of sale selected for visit (25 per district) was based on practical considerations and resulted in a relatively small sample of ampoules available for chemical testing.

The sampling frame may not have been 100% exhaustive, given the informal nature of some drug sellers. However, study results were strikingly similar across three diverse districts, and this is unlikely to result from sampling error.

Introduction

The most commonly used uterotonic drugs in poor countries are injectable oxytocin, injectable ergometrine and misoprostol tablets. Injectable methylergometrine, injectable syntometrine and ergometrine tablets are also used. Oxytocin, ergometrine and misoprostol are included in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines.1 Based on existing data, the WHO considers oxytocin the drug of choice for postpartum haemorrhage prevention and treatment where a skilled care giver is available, safe injection practices are ensured and refrigeration is feasible.2 Oxytocin is also included in the new WHO list of priority medicines for mothers and children for prevention of postpartum haemorrhage.3 As uterotonics are also used for other obstetric indications (induction, augmentation of labour), the importance of access to potent uterotonics throughout the antepartum and early postpartum periods is indisputable.

Given that postpartum haemorrhage is a leading direct cause of maternal death in many poor countries, large-scale efforts have focused on in-service clinical training for postpartum haemorrhage prevention and treatment, which requires uterotonic drugs. However, best practice for long-term storage for all injectable uterotonics is refrigeration, which is a key logistical constraint for scale up of postpartum haemorrhage reduction strategies and is a general challenge for maternity services without consistent electricity.

In 1993, a WHO simulation study testing the stability of injectable uterotonic drugs showed that oxytocin lost no active ingredient after 12 months under refrigeration (4°C–8°C), lost 3%–7% active ingredient after 12 months at 21°C–25°C, lost 9%–19% active ingredient after 12 months at 30°C and was unaffected by exposure to light. Ergometrine was shown to be much less stable, losing 5% of its active ingredient after 12 months at 4°–8°C when stored in the dark, losing more than 90% of its active ingredient when stored for 12 months at 21°–25°C exposed to light.4

Few other studies were identified, which addressed degradation of uterotonics resulting from environmental exposure. Those that were identified are not recent, and all focused only on oral and injectable preparations of oxytocins: ergometrine, methylergometrine and oxytocin. Exact estimates of the shelf life of oxytocin and ergometrine varied across the studies, but in general, the results of these studies concurred with the conclusion of the WHO simulation study that ergometrine was much less stable under tropical conditions than oxytocin, but that both posed public health concerns in contexts without access to refrigeration.5–8 No studies were identified, which addressed the potency of misoprostol or the existence of counterfeit or substandard (ie, drugs which at manufacture do not meet the specifications reported by the manufacturer) uterotonics.

In Ghana, there are approximately 1600 retail pharmacies and 10 000 chemical sellers, of which 7000 are registered with the Pharmacy Council, the regulatory body of the Ministry of Health tasked with ensuring the quality, accessibility and equitable distribution of pharmaceutical services, and the Association of Chemical Sellers.9 In Ghana, only those pharmacies with a License A are legally authorised to sell uterotonic drugs.

The objectives of this study were (1) to assess the population's access to uterotonics with and without prescription and (2) to assess potency of injectable oxytocin and ergometrine from varying sources from three contrasting districts in Ghana.

Methods

The study design involved research assistants simulating clients to purchase ampoules of oxytocin and ergometrine from different types of points of sale. In an effort to design a representative sample of uterotonic points of sale, one district was selected from each of the three ecological regions of the country (coastal, forest and savannah), which also differ on major socioeconomic indicators.

In August 2010, a research assistant travelled throughout the selected districts to compile a list including all pharmacies and chemical shops. In addition, he was asked to compile information on informal points of sale such as markets from which drugs might be purchased from stationed sellers and mobile drug peddlers. All efforts were made to compile an exhaustive list, acknowledging that this is nearly impossible given the informal and transient nature of some points of sale. Upon the research assistant's return to Accra, pharmacies and chemical shops in each district were consecutively numbered, a random start number was selected and points of sale were systematically selected with a constant sampling interval until a sample of 25 points of sale were identified in each district. In Yendi and Kintampo North, all the chemical shops and pharmacies identified during the listing exercise were selected for a visit.

Two months later, a team of nine research assistants simulated clients by visiting each selected point of sale and requested drugs used by pregnant women to hasten their delivery, adding that the drugs were needed for his/her sister, who was soon due to deliver.

There was no verbal or written informed consent for this study, as consent of the salesperson would have undermined the simulation. If the salesperson requested a prescription, the client provided a prescription for oxytocin and ergometrine, which was obtained from a Ghana Health Service collaborator in Accra. This was done for the following two reasons: (1) for human subjects purposes to avoid putting the salesperson in the position of being asked to sell drugs to a client without a prescription even after the salesperson had asked for one and (2) to ensure a sufficient sample of ampoules for chemical assay later. If the salesperson recommended that the client go elsewhere, the research assistants substituted the recommended location for the selected site.

Purchased ampoules were placed in plastic bags with coded information regarding the date of purchase, expiry date of the ampoule, type of point of sale and district name. These bags were placed in vaccine cold chain carriers just after purchase and were placed in the cold room or refrigerator of the district hospital as quickly as possible and not later than the evening of the day of purchase. Ampoules remained under refrigeration in the district hospitals for 0–13 days before being transported in the cold chain to Accra. In Accra, samples were refrigerated for up to 1 week, after which all samples were submitted to the Ghana Food and Drugs Board. The Food and Drugs Board documented that all ampoules were delivered under cold chain conditions. Samples were refrigerated until analysis.

Samples were analysed according to the Finished Pharmaceutical Product specifications of the British Pharmacopoeia, 2010 edition, as all the samples had the British Pharmacopoeia as their specification. The US Pharmacopeia chemical reference standards for ergonovine maleate (ergometrine maleate) RS and oxytocin RS were used as standard comparators in the analysis: for oxytocin, 46 oxytocin units per phial, USP Reference Standard, Lot F1G134, Cat. No. 1491300; and for ergonovine maleate, 100 mg, USP Reference Standard, Cat. No. 24000. The ampoules were tested without blinding to product packaging, as information on the packaging is required for testing. However, the manufacturer name was not included among assay results, as required for ethical approval of the study.

This study was approved by institutional review boards at the Ghana Health Service in Accra, Ghana; PATH in Seattle, Washington; and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the study districts are provided in table 1. Yendi district is located in the Northern Region and is socioeconomically disadvantaged relative to the other two districts. Socioeconomic indicators for Kintampo North in Brong-Ahafo Region fall between those of the Northern and Western Regions in which Ahanta West District is located.10

Table 1.

Regional socioeconomic indicators for study districts

| Characteristic | Northern Region (Yendi) | Brong-Ahafo (Kintampo North) | Western Region (Ahanta West) |

| % of reproductive aged women with no education | 67.5 | 27.7 | 19 |

| % of women using modern contraception | 7.3 | 17.5 | 19.9 |

| % of births assisted by a medically trained attendant | 27.3 | 56.9 | 53.6 |

Source: Ghana Health Service, Ghana Statistical Service, Macro International.10

Sixty-nine visits to formal points of sale and 21 visits to informal points of sale were made in total. Formal points of sale included private pharmacies, chemical shops and public health facility pharmacies. Informal points of sale included market places, mobile peddlers and herbal or home clinics. Although the original plan was to restrict sampling to private points of sale, salespeople occasionally either declined to sell uterotonic drugs or did not have any to sell and recommended that the client go to the nearby public health facility pharmacy. Thus, as described in table 2, 10% of the 69 commercial points of sale visited were public health facility pharmacies. Eighty-three per cent of visits to formal points of sale were to chemical shops, with only 7% to private pharmacies. In Kintampo North and Yendi districts, all chemical shops identified during the August listing exercise were visited except for two—one due to inaccessible roads and one which was closed for the duration of fieldwork. In Ahanta West, research assistants went to pharmacies across district lines at the recommendation of a salesperson. Half of the informal points of sale were mobile peddlers (11 of 21), followed by market places (8 of 21). The list of informal points of sale, which were visited, however, was opportunistic.

Table 2.

Numbers and per cent distribution of the points of sale visited by simulated clients by district

| District |

|||||

| Yendi | Kintampo North | Ahanta West | Total | Total % | |

| Number of commercial points of sale | |||||

| Private pharmacies | 0 | 1 | 4* | 5 | 7.3 |

| Chemical shops/sellers | 23 | 17 | 17 | 57 | 82.6 |

| Public health facility pharmacies | 6 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 10.1 |

| Total | 29 | 19 | 21 | 69 | 100 |

| Number of informal points of sale | |||||

| Markets | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 38.1 |

| Home/herbal clinics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 9.5 |

| Mobile peddlers | 4 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 52.4 |

| Total | 7 | 8 | 6 | 21 | 100 |

All pharmacies were located outside the Ahanta West in a contiguous district.

A total of 101 ampoules were collected via the simulated client exercise: 46 ampoules of oxytocin 10 IU and 55 ampoules of ergometrine 0.5 mg. Tables 3 and 4 present the per cent distribution of purchased ampoules of oxytocin and ergometrine by district and by type of point of sale, respectively. Only 15% of the ampoules purchased were from Yendi district, with approximately 42% each purchased by the teams in Ahanta West and Kintampo North. To note, there are no pharmacies in Ahanta West District, the four pharmacies visited by the simulated clients from Ahanta West were in a neighbouring district to which they were referred. Approximately one third of the 101 ampoules were purchased from chemical sellers, who in theory are not licensed to sell uterotonic drugs. More than one in five ampoules (22%) were purchased in public health facility pharmacies. In most cases, the simulated clients purchased one ampoule each of ergometrine and oxytocin. At four points of sale, simulated clients were sold five ampoules of both drugs, and at one site, they were sold 10 ergometrine ampoules.

Table 3.

Per cent distribution of purchased oxytocin and ergometrine ampoules by district

| District | Oxytocin (%) | Ergometrine (%) |

| Yendi | 15.2 | 14.5 |

| Kintampo | 30.4 | 51 |

| Ahanta West | 52.2 | 34.5 |

| Missing | 2.2 | 0 |

| Total % (N) | 100 (46) | 100 (55) |

Table 4.

Per cent distribution of purchased oxytocin and ergometrine ampoules by type of point of sale

| Source of purchase | Oxytocin (%) | Ergometrine (%) |

| Private pharmacies | 32.6 | 58.2 |

| Chemical shops/sellers | 39.1 | 23.6 |

| Public health facility pharmacies | 26.1 | 18.2 |

| Missing | 2.2 | 0 |

| Total % (N) | 100 (46) | 100 (55) |

Products other than injectable uterotonics were offered to and purchased by the simulated clients, including ergometrine tablets, misoprostol and Buscopan (used for labour induction in some settings). None of these products were tested for active ingredients. No uterotonics were successfully purchased from mobile peddlers, herbal/home clinics, or markets. A variety of black or red powders or dark-coloured roots were purchased from mobile peddlers in response to the simulated client's request for a product that would hasten labour. Traditional preparations were not tested for uterotonic properties.

Table 5 presents the distribution of the percentage of active ingredient in the purchased ampoules of oxytocin and ergometrine. Among the 46 oxytocin ampoules, 26% (11 ampoules) met British Pharmacopoeia specifications, showing 90%–110% active ingredient. Only 4% (two ampoules) of oxytocin ampoules had expired. None of the 55 ergometrine ampoules met the British Pharmacopoeia specification, with a level of active ingredient between 90% and 110%. Seventy-six per cent of the ergometrine ampoules showed <60% active ingredient. One ergometrine ampoule showed 0% active ingredient and one showed 120% active ingredient. None of the ergometrine ampoules had expired. The median percentages of active ingredients were 64% and 50% for oxytocin and ergometrine, respectively.

Table 5.

Per cent distribution of the assay percentage of active ingredient in purchased ampoules of oxytocin and ergometrine

| Assay percentage | Oxytocin 10 IU (%) | Ergometrine 0.5 mg (%) |

| 0 | 0 | 1.8 |

| 1–39 | 23.9 | 23.7 |

| 40–59 | 8.7 | 50.8 |

| 60–89 | 41.3 | 21.9 |

| 90–110 | 26.1 | 0 |

| >110 | 0 | 1.8 |

| Total % (N) | 100 (46) | 100 (55) |

| Median % | 64 | 50.5 |

| Per cent expired | 4.3 (2) | 0 (0) |

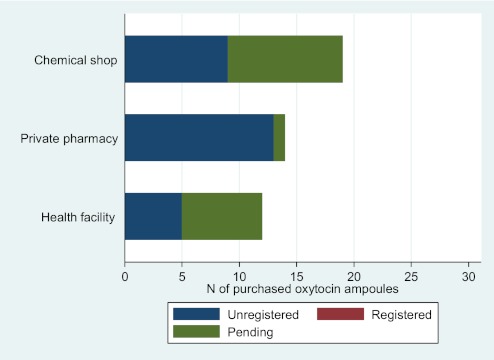

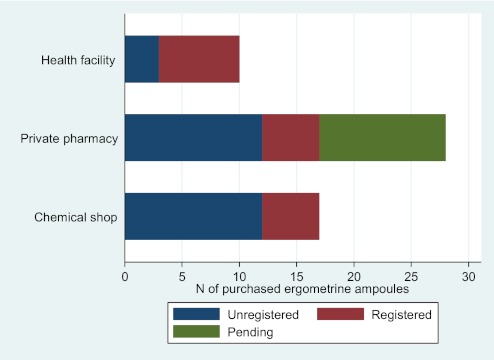

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the number of ampoules of oxytocin and ergometrine by in-country registration status of the product and by type of point of sale. None of the oxytocin ampoules purchased were from a registered manufacturer of oxytocin. Eighteen of the oxytocin samples (39%) were from manufacturers whose registration status was pending, and 28 (61%) were from unregistered manufacturers of oxytocin. Unregistered oxytocin was purchased from chemical shops, private pharmacies and public health facility pharmacies. All the oxytocin ampoules from unregistered manufacturers were outside specification for active ingredient. One third of the oxytocin ampoules from manufacturers with pending registration status were outside specification for active ingredient (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Number of purchased ampoules of oxytocin by in-country registration status of the product and by type of point of sale.

Figure 2.

Number of purchased ampoules of ergometrine by in-country registration status of the product and by type of point of sale.

For ergometrine, 17 ampoules (31%) were from registered manufacturers of ergometrine, 11 (20%) were from manufacturers whose registration status was pending and 27 (49%) were from unregistered manufacturers of ergometrine (including the ampoule with 0% active ingredient). As with oxytocin, unregistered ergometrine was purchased from all types of points of sale. All ergometrine ampoules were outside specification for active ingredient.

It was not possible to quantify results regarding the need for a prescription to purchase uterotonics. In some cases, salespeople made vague mention of the need for a prescription, but never actually requested one, or they asked for a prescription but never looked at it. Where prescriptions were requested, all were given back to the simulated client. In some cases where clients were referred to a public health facility pharmacy, the simulation ceased and a healthcare provider accompanied the research assistant to the facility pharmacy. In short, it appears that it was common but not universal that the salesperson requested a prescription. The research assistants also noted that salespeople often assumed they were interested in uterotonic drugs for abortion purposes, despite their story about a woman who was soon to deliver.

Discussion

Four messages resound from the analysis of this exploratory study: (1) quality of uterotonics is likely a serious problem, at least in these districts in Ghana; 89% of all ampoules tested in this study did not meet the specifications for active ingredient; (2) the low level of active ingredient in these ampoules is not due to old drugs; only 2% of these ampoules had expired; (3) there is little enforcement of the restriction against chemical shops selling uterotonics or of the sale of unregistered uterotonics in these districts and (4) inactive uterotonics are not restricted to the private sector; uterotonics outside specification were purchased from private and public sources. It is also clear that public and private sources procure unregistered uterotonics. It was not possible to quantify results on the need for a prescription to purchase uterotonics, though in many cases, the client was at least vaguely asked for a prescription.

There are a number of strengths and limitations to this study. Strengths include the fact that an up-to-date listing of points of sale was compiled specifically for this study; a sample of randomly selected sites was visited; and in two of three districts, the selected points of sale represented all the existing accessible chemical sellers and pharmacies. The simulated client approach would also have prevented possible bias in the selection of ampoules for testing. Limitations include the fact that the sampling frame may not have been 100% exhaustive, given the informal nature of some drug sellers, and that the number of points of sale selected for visit (25 per district) was based on practical considerations and resulted in a relatively small sample of ampoules available for chemical testing. Study results were strikingly similar across three diverse districts, however, and this is unlikely to result from sampling error. Some misclassification between chemical sellers and pharmacies was also possible, as shops were classified based on their exterior signage. As simulated clients, the research assistants could not ask questions regarding a shop's licenses or the qualifications of the salesperson.

Study results were shared with the Ghana Food and Drugs Board and other interested parties and clearly warrant in-depth investigation by both the Food and Drugs Board and the Ghana Health Service. The difficulties of the Ghana Food and Drugs Board in monitoring and addressing counterfeit and substandard drugs have been highlighted in a recent private health sector assessment by the World Bank.11 A 2010 evaluation of the efforts of the Medicines Transparency Alliance (META) in Ghana includes among its 10 recommendations that each META Governing Council meeting should include discussion of a specific substantive drug-related issue and that these discussions should be informed by a fact sheet of existing information developed specifically for this purpose.9 The results of this study strongly support development of a fact sheet on uterotonic drug quality by the META Governing Council, as well as consideration of including one or more uterotonic drugs on the list of tracer drugs in Ghana. The common and accepted practice by public health facilities of purchasing additional drugs on the private market when centrally distributed stocks are low requires closer monitoring by the Ghana Health Service to prevent the purchase of unregistered drugs.

This study also raises a host of questions, which are not specific to Ghana. For example, given the need for additional data on uterotonic drug quality in poor countries, which approaches to data collection and sampling should be promoted and for which objectives? Simulated clients were used in this study to ensure an unbiased selection of ampoules for chemical testing and to assess how well pharmacies follow existing regulations requiring a prescription for the sale of uterotonic drugs. An important consequence of using simulated clients, however, is that it precludes data collection on why ampoules were out of specification for active ingredients. In the absence of information on drug quality at manufacture and packaging, and storage conditions along the distribution chain, it is not possible to determine whether the cause is counterfeit, substandard or degraded drugs. Although it is likely that at least one reason for the low percentages of active ingredients is unrefrigerated storage (for both oxytocin and ergometrine) and/or exposure to light (for ergometrine), one does not know at which points along the distribution chain this may have occurred. These limitations should be seriously considered when deciding on study design. Finally, the study also raises the question of which uterotonic drugs should be tested. In this study, it was considered unnecessary to test misoprostol. However, given the rapid expansion of the availability of and demand for misoprostol, particularly in South and Southeast Asia,12 counterfeit misoprostol is likely to become a problem and should be considered for inclusion in future studies.

The results of this study are sufficient to raise serious concerns regarding the quality of oxytocin and ergometrine, particularly at the peripheral level in Ghana, and potentially in other low-income countries. While efforts to reduce maternal mortality have focused on training health workers to prevent and treat postpartum haemorrhage, these efforts and resources are undermined if health workers do not have access to high-quality uterotonics. These results suggest that any focused postpartum haemorrhage reduction strategy also requires ongoing surveillance of uterotonic drugs, enforcement of drug registration and pharmaceutical licensing regulations, and increased attention to drug storage and procurement. Postmarketing surveillance of drug quality in low-income countries is often restricted to disease-specific well-financed health programmes such as those that rely on antiretrovirals, antibiotics and antimalarial drugs. Maternal health programmes must adopt and fund the same approach to drug quality as is standard in programmes addressing infectious disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Stephen Kwankye, Delali Badasu, Kamil Fuseini, Henry Tagoe, Adriana Biney and Nanaa Boakye of the Regional Institute for Population Studies for assisting with data collection. We also recognise John Gyapong (Ghana Health Service) and Gloria Quansah-Asare (Ghana Ministry of Health) for their support throughout the implementation and analysis phases of the study. We also acknowledge Deborah Armbruster, formerly of PATH, for her contribution to the initiation and design of the Oxytocin Initiative and Alice Levisay and Sadaf Khan of PATH for their assistance in the editing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

To cite: Stanton C, Koski A, Cofie P, et al. Uterotonic drug quality: an assessment of the potency of injectable uterotonic drugs purchased by simulated clients in three districts in Ghana. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000431. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000431

Contributors: CS assisted in the design of the study, analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the paper. AK, PC and EM assisted with the design of the study, oversaw data collection and assisted with editing the paper. BLG and SB provided technical guidance throughout the study, particularly regarding potency testing of the uterotonic drugs and assisted with the editing of the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) CS, AK and EM have contract support from PATH for the submitted work and that PC, BLG and SB have grant support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work; (2) CS, AK, PC, EM, BG and SB have no relationships with any companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) CS, AK, PC, EM, BG and SB have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work. This research was supported by the Oxytocin Initiative project at PATH with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The funders of the study had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation of study results, writing of this manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors had access to and full control of all primary data. The study was undertaken by PATH, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Regional Institute for Population Studies at the University of Ghana.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from the Ghana Food and Drugs Board for the chemical testing of the purchased ampoules of uterotonic drugs are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.WHO WHO Model List of Essential Medicines; 16th List (Updated). Geneva, 2010. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO WHO Statement Regarding the Use of Misoprostol for Postpartum Haemorrhage Prevention and Treatment. Geneva: Department of Reproductive Health and Research, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO WHO List of Priority Medicines for Mothers and Children. Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stability of Injectable Oxytocics in Tropical Climates; Results of Field Surveys and Simulation Studies on Ergometrine, Methylergometrine and Oxytocin. Geneva: Action Program on Essential Drugs, World Health Organisation, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Groot AN, Hekster YA, Vree TB, et al. Ergometrine and methylergometrine tablets are not stable under simulated tropical conditions. J Clin Pharm Ther 1995;20:109–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Groot AN, Hekster YA, Vree TB, et al. Oxytocin and desamino-oxytocin tablets are not stable under simulated tropical conditions. J Clin Pharm Ther 1995;20:115–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogerzeil HV, Battersby A, Srdanovic V, et al. Stability of essential drugs during shipment to the tropics. BMJ 1992;304:210–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nazerali H, Hogerzeil HV. The quality and stability of essential drugs in rural Zimbabwe: controlled longitudinal study. BMJ 1998;317:512–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waddington CM, Coleman NA. Evaluation of the MeTA Phase 1 2009–2010; Ghana Country Report. London: HLSP, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghana Health Service, Ghana Statistical Service, Macro International Ghana Maternal Health Survey, 2009. Calverton, Maryland, USA [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makinen MS, Bitran S, Adjei R, et al. Private Health Sector Assessment in Ghana. Washington DC: The World Bank, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez MM, Coeytaux F, de Leon RG, et al. Assessing the global availability of misoprostol. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:180–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.