Abstract

Purpose: Bleeding is the major side effect of thrombolysis with alteplase (tissue plasminogen activator, t-PA) used for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Life-threatening intracranial, retroperitoneal, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and genitourinary bleeding can occur with the use of t-PA. Vitreo-retinal bleeding in the context of acute ischemic stroke treatment has not been reported in the literature before and therefore is not posed as a potential risk during decision making. Here we describe the first reported case of vitreo-retinal hemorrhage due to alteplase administration in a patient with acute ischemic stroke. Summary: An 84-year-old white male presented to the emergency room with complaints of right arm and leg weakness. The onset of symptoms was approximately 30 min prior to presentation to the emergency room. After ruling out contraindications including the presence of hemorrhage on head CT scan, patient was administered alteplase within 2 hours of symptom onset. Four hours after the administration of alteplase, the patient developed right-sided vision changes. A repeat CT scan demonstrated a newly developed right intraocular hemorrhage. Throughout the hospital course, patient’s neurological status improved, but he continued to have right-sided visual loss. Conclusion: Clinicians should be aware of the potential for ocular hemorrhage especially in high-risk patients. The likelihood of a subsequent vision-loss needs to be therefore discussed with the patient and family in such situations.

Keywords: stroke, alteplase, ocular, retinal, hemorrhage, thrombolysis, t-PA

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes of death in United States (Roger et al., 2011). The use of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) in eligible patients with acute ischemic stroke has been shown to improve neurological recovery and reduce the incidence of disability (The National Institute of Neurological Disorders, 1995; Package Insert Alteplase, 2005). Prior to the administration of t-PA, the benefits and risks of this therapy are explained to the patients. Risks mainly include intracranial, retroperitoneal, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and/or genitourinary bleeding. The potential for intraocular hemorrhage and subsequent visual loss is not part of the discussion mostly due to the rarity of this situation and ignorance of the factors that may increase risk. A review of literature using MEDLINE and EMBASE databases utilizing the search terms “tissue plasminogen activator,” “acute ischemic stroke,” “thrombolysis,” “ocular,” and “hemorrhage” failed to retrieve any reports of ocular bleeding due to t-PA in the context of acute ischemic stroke treatment. On the other hand, in patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI), ocular hemorrhage has been reported as a very uncommon complication of thrombolytic therapy (Mahaffey et al., 1997). Intraocular hemorrhage after reteplase administration has been reported in a 66-year-old man with a history of hypertensive retinopathy who presented with acute MI (Kaba et al., 2005). This patient was eventually able to perceive hand movements with the affected eye. Similarly, other cases have been reported in patients with acute MI and majority of them had a history of ophthalmic disease (Chorich et al., 1998; Berry et al., 2002; Djalilian et al., 2003).

Intraocular hemorrhage and subsequent visual loss as a result of treatment for ischemic stroke can be a devastating complication even if the patient otherwise has a significant neurological recovery. Here we describe the first reported case of vitreo-retinal hemorrhage leading to permanent visual loss after t-PA administration in a patient with acute ischemic stroke.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old white male presented to the emergency room with complaints of right arm and leg weakness. The onset of symptoms was approximately 30 minutes prior to presentation to the emergency room. The patient had no dysarthria, aphasia, vision, or hearing changes. There was no history of a recent fall, injury, or seizures. Past medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, bilateral retinopathy from long-standing diabetes and hypertension, bilateral cataracts, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and invasive adenocarcinoma. Past surgical history included laminectomy (1 year prior) and colonoscopy with polyp removal (2 days prior). The only drug allergy the patient had was to penicillin. Prior to admission, his medications were aspirin, metformin, metoprolol, multivitamin, and simvastatin. Social and family histories were not pertinent to this case.

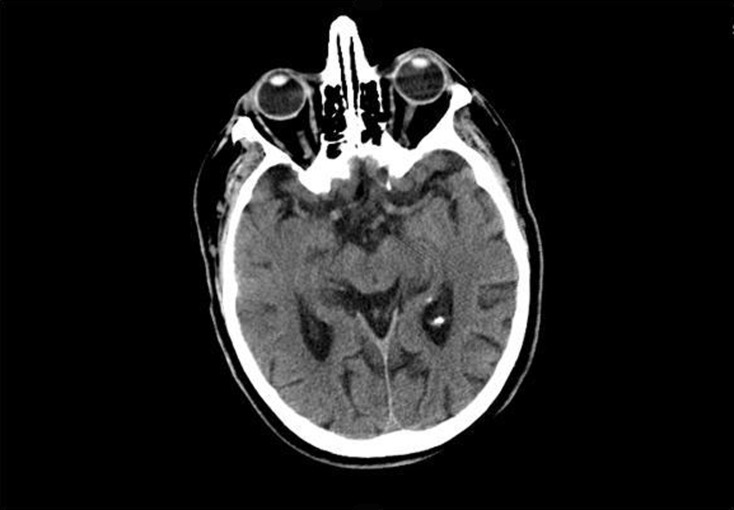

In the emergency room, patient’s vital signs were stable with an average blood pressure around 160/60 mmHg. Patient’s physical examination revealed weakness and decreased sensation on the right side. Of note, patient’s eye exam was normal with no vision changes. An urgent CT scan of the head was performed which was negative for any intracranial or ocular hemorrhage (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CT scan image prior to t-PA.

The decision to administer t-PA was made since the patient met the inclusion criteria and had no contraindications (The National Institute of Neurological Disorders, 1995; Package Insert Alteplase, 2005). The risks and benefits of therapy were well explained to the patient and his family. The potential for intracranial hemorrhage and specifically gastrointestinal hemorrhage, in view of patient’s recent colonoscopy, were also discussed in detail. Within 2 hours after the onset of symptoms, patient was administered alteplase, according to the standard weight-based dosing protocol (Package Insert Alteplase, 2005). Patient was frequently evaluated for any change in neurological status and his blood pressure was appropriately maintained throughout this time period.

Four hours after the administration of alteplase, the patient developed bright-red-blood-per-rectum and new onset black–red visual loss in the right eye. Other than the visual changes, rest of the physical and neurological exam remained unchanged. A repeat CT scan demonstrated a new right intraocular hemorrhage (Figure 2). There was no evolution of the infarct or evidence of hemorrhage in the brain. Patient’s hemoglobin and vital signs remained relatively stable during this time. Evaluation by ophthalmology and neurology consultants confirmed the presence of a right-sided vitreo-retinal hemorrhage. Follow-up MRI of the brain confirmed the presence of the intraocular bleeding along with an acute/subacute left parietal infarct.

Figure 2.

CT scan image demonstrating ocular hemorrhage.

Throughout the hospital stay, patient continued to have right ocular visual loss even though his neurological status improved. Eventually, the patient underwent in-patient rehabilitation and was subsequently discharged without any further complications. At discharge, patient was almost back to his baseline in regards to activities and functionality except for visual loss in the right eye. Follow-up 8 months later revealed that patient had no vision in the right eye except for perception of light in the periphery.

Discussion

Previously reported intraocular hemorrhage due to t-PA was in acute MI patients. The case we described here is the first one to report permanent visual loss as a complication of t-PA in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Since the patient had no visual deficits or radiological evidence of intraocular hemorrhage prior to admission, this complication can be attributed to the use of t-PA. Similar to previously reported cases, a history of retinopathy in our patient makes one wonder if patients with a history of ocular disease are at higher risk for intraocular hemorrhage leading to visual loss. This being a single case report in a patient with acute ischemic stroke, more reports and/or studies are required to confirm this relationship.

Bleeding from any organ or site is a well-known risk of using t-PA. Nonetheless, permanent loss of vision can be a very difficult situation for some patients, in spite of the potential neurological recovery they might have. Even though salvaging the brain is of greater importance, the possibility of this complication needs to be discussed with high-risk patients to help make an informed decision.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of the risk of visual loss after t-PA administration in high-risk patients. In patients with prior history of ocular disease, the risk of hemorrhage and subsequent irreversible vision loss needs to be discussed with the patient and family.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Berry C., Weir C., Hammer H. (2002). A case of intraocular haemorrhage secondary to thrombolytic therapy. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 80, 561–562 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800522_1.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorich L., Derick R., Chambers R., Cahill K. V., Quartetti E. J., Fry J. A., Bush C. A. (1998). Hemorrhagic ocular complications associated with the use of systemic thrombolytic agents. Ophthalmology 105, 428–431 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)93023-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djalilian A. R., Cantrill H. C., Samuelson T. W. (2003). Intraocular hemorrhage after systemic thrombolytic therapy in a patient with exudative macular degeneration. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 13, 96–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaba R. A., Cox D., Lewis A., Bloom P., Dubrey S. (2005). Intraocular haemorrhage after thrombolysis. Lancet 365, 330. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17788-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey K. W., Granger C. B., Toth C. A., White H. D., Stebbins A. L., Barbash G. I., Vahanian A., Topol E. J., Califf R. M. (1997). Diabetic retinopathy should not be a contraindication to thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: review of ocular hemorrhage incidence and location in the GUSTO-I trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 30, 1606–1610 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00394-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Package Insert Alteplase. (2005). Activase (Alteplase) Product Information. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech [Google Scholar]

- Roger V. L., Go A. S., Lloyd-Jones D. M., Adams R. J., Berry J. D., Brown T. M., Carnethon M. R., Dai S., de Simone G., Ford E. S., Fox C. S., Fullerton H. J., Gillespie C., Greenlund K. J., Hailpern S. M., Heit J. A., Ho P. M., Howard V. J., Kissela B. M., Kittner S. J., Lackland D. T., Lichtman J. H., Lisabeth L. D., Makuc D. M., Marcus G. M., Marelli A., Matchar D. B., McDermott M. M., Meigs J. B., Moy C. S., Mozaffarian D., Mussolino M. E., Nichol G., Paynter N. P., Rosamond W. D., Sorlie P. D., Stafford R. S., Turan T. N., Turner M. B., Wong N. D., Wylie-Rosett J., American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee (2011). Heart disease, and stroke statistics – 2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123, e18–e209 [Erratum, Circulation 2011; 123, e240.] 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group (1995). Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 333, 1581–1588 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]