Abstract

Poliovirus (PV) modifies membrane-trafficking machinery in host cells for its viral RNA replication. To date, ARF1, ACBD3, BIG1/BIG2, GBF1, RTN3, and PI4KB have been identified as host factors of enterovirus (EV), including PV, involved in membrane traffic. In this study, we performed small interfering RNA (siRNA) screening targeting membrane-trafficking genes for host factors required for PV replication. We identified valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97) as a host factor of PV replication required after viral protein synthesis, and its ATPase activity was essential for PV replication. VCP colocalized with viral proteins 2BC/2C and 3AB/3B in PV-infected cells and showed an interaction with 2BC and 3AB but not with 2C and 3A. Knockdown of VCP did not suppress the replication of coxsackievirus B3 or Aichi virus. A VCP-knockdown-resistant PV mutant had an A4881G (a mutation of E253G in 2C) mutation, which is known as a determinant of a secretion inhibition-negative phenotype. However, knockdown of VCP did not affect the inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of each individual viral protein. These results suggested that VCP is a host factor required for viral RNA replication of PV among membrane-trafficking proteins and provides a novel link between cellular protein secretion and viral RNA replication.

INTRODUCTION

Poliovirus (PV) is a small nonenveloped virus with a single-strand positive genomic RNA of about 7,500 nucleotides (nt) belonging to Human enterovirus C in the genus Enterovirus, the family Picornaviridae. PV is the causative agent of poliomyelitis, which is caused by the destruction of motor neurons by the direct infection of PV in the cells (17, 26). With established live attenuated oral PV vaccine (OPV) and inactivated PV vaccine (IPV) for PV (72, 73), the global eradication program for poliomyelitis has been continued by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) of the World Health Organization (WHO) since 1988. In the eradication program for poliomyelitis, antivirals for PV are anticipated to have some roles in the posteradication era of PV (24, 25) although currently there is no antiviral available for therapeutic use for PV infection.

Antiviral candidates have served as useful tools for the study of PV infection in addition to their potential use in therapy. Antivirals for PV have been identified at every stage of PV infection, including binding to cells, uncoating, protein synthesis, RNA replication, and encapsidation (reviewed in references 9, 21, and 70). As viral RNA replication inhibitors, guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl), brefeldin A (BFA), and PIK93 are well characterized in terms of the target and the mechanism of inhibition and also represent predominant groups of replication inhibitor. GuHCl targets viral 2C and/or 2BC proteins along with some benzimidazole derivatives (30, 35, 77) and inhibits initiation of negative-strand RNA synthesis (10, 16, 20). BFA is an inhibitor of BFA-sensitive guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and suppresses activation of ADP ribosylation factors (Arfs) by stabilizing a transitional inactive complex, the Arf-GDP-Sec7 domain of GEFs (66). BFA inhibits replication of enterovirus (EV) including PV by targeting GBF1 (11, 27, 44, 60, 91). The inhibitory effect of BFA is limited in EV replication and not conserved in general picornavirus replication (e.g., replication of encephalomyocarditis virus [EMCV] is insensitive for BFA) (44). Other GEFs, BIG1/BIG2, are also required for EV replication via direct and indirect interaction with viral 3A and 3CD proteins (12, 91). PIK93, a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III beta (PI4KB) inhibitor, has been identified to act as an antienterovirus compound (43). PIK93 inhibits PI4KB activity to suppress interaction of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate with viral 3D polymerase on the reorganized membrane vesicles (43). Recent analyses of picornavirus 3A proteins suggest an important role of ACBD3, which is a Golgi protein interacting with giantin (80) to form a PI4KB/ACBD3/3A protein complex for viral replication (37, 75). Interestingly, PIK93 belongs to a group of anti-PV compounds in terms of a resistance mutation of PV (G5318A [A70T mutation in 3A]) that confers resistance to enviroxime (3). Enviroxime is an antipicornavirus compound that inhibits positive-strand RNA synthesis by preventing normal formation of replication complex (18, 40, 93). To date, several anti-PV compounds have been identified in this group as enviroxime-like compounds (3, 5–7, 31). One of the enviroxime-like compounds, the PI4KB-specific inhibitor T-00127-HEV1, targets PI4KB activity for its anti-PV activity but does not have anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) activity, suggesting that PI4KB is a target of enviroxime-like compounds in picornavirus replication (3). An antipicornavirus compound, Ro-09-0179, targets the Golgi apparatus as well as BFA (47, 74), underscoring the importance of the membrane-trafficking pathway not only for PV replication but also as a target pathway for an antiviral drug.

The membrane-trafficking pathway provides general targets, including Rab and Arf families, for replication of bacteria and viruses (reviewed in reference 67). In PV replication, ARF1, ACBD3, GBF1, BIG1/2, RTN3, and PI4KB are involved in the membrane trafficking pathway (12, 37, 43, 75, 83, 91). In PV infection, the membrane traffic pathway is utilized for the formation of the replication complex and for nonlytic virus release from the infected cells (48, 84). Viral proteins 3A and 2BC are involved in formation of vesicles similar to that observed in PV-infected cells (82) and in inhibition of cellular protein secretion (34). The inhibitory effect of 3A on cellular protein secretion is not generally conserved in picornavirus (23) but might be compensated by other viral proteins (e.g., 2BC protein for foot-and-mouth disease virus infection) (62). Cellular protein secretion is inhibited during PV infection (34); however, PV mutants that did not inhibit cellular protein secretion have been isolated and did not show a significant growth defect (15, 19, 32). Therefore, the importance of cellular protein secretion in picornavirus infection as well as the responsible host factors remained to be elucidated.

In the present study, we have performed a screening with a library of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting membrane-trafficking genes to identify host factors involved in PV replication. We identified valosin-containing protein (VCP) as a novel host factor for PV replication. VCP is a cellular ATPase that belongs to the class I AAA+ (ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities) family (92) and has roles in a variety of cellular processes. We found that ATPase activity of VCP is essential for PV replication and that viral proteins 2BC and 3AB interact with VCP. Knockdown of VCP did not suppress the replication of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3), which is a member of another EV species, Human enterovirus B, or of Aichi virus (AV), which is a member of another genus, Kobuvirus, of the family Picornaviridae. A PV-resistant mutant that showed improved growth in VCP-knockdown cells contained the mutation A4881G (E253G in 2C [2C-E253G]), which is known as the determinant of a secretion inhibition-negative phenotype of a PV mutant (19). However, knockdown of VCP did not suppress the inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of viral proteins 2B, 2BC, 3A, and 3AB. These results suggested that VCP is a host factor required for viral RNA replication of PV among membrane-trafficking proteins and provides a novel link between cellular protein secretion and viral RNA replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, plasmids, antibodies, and siRNA library.

RD cells (human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line) and HEK293 cells (human embryonic kidney cells) were cultured as monolayers in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). RD cells were used for titration of virus and characterization of eeyarestatin I (EerI). HEK293 cells were used for siRNA screening to identify host factors of PV replication. PV pseudovirus (TE-PV-Fluc mc), which encapsidated a luciferase-encoding PV replicon with capsid proteins derived from PV1 (Mahoney), was used for siRNA screening according to the condition established for antienterovirus compound screening (1, 4, 7). Expression vectors for Flag-tagged and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-fused VCP mutants [wild-type (wt) VCP, VCP(K524A), VCP(R191Q), and VCP(A232E), constructed based on mouse VCP sequence that has 100% amino acid similarity to human VCP; mutated residues are indicated in parentheses] were kind gifts from Akira Kakizuka (Laboratory of Functional Biology, Kyoto University Graduate School of Biostudies, Japan) (59). A cDNA clone of an Aichi virus replicon was a generous gift from Jun Sasaki (Department of Virology and Parasitology, Fujita Health School of Medicine) (63). EGFP fusions of VCPs with FLAG tags on their C termini were used for immunoprecipitation. Antibodies against PV 3A and 3B were raised in rabbits with peptides CDLLQAVDSQEVRDY (amino acids [aa] 23 to 36 of PV 3A protein) and CNKKPNVPTIRTAKVQ (amino acids 8 to 22 of PV 3B protein), respectively. Expression vectors for PV proteins (2B, 2BC, 2C, 3A, and 3AB) were constructed with pKS435, where expression of viral proteins was controlled under the HEF-1α promoter (4). 3AB mutant proteins used in this study are as follows: wild-type 3AB, 3AB-His (3AB protein with a six-histidine tag), wild-type 3A, 3AB protein lacking amino acids 61 to 87 of 3A protein [3A(Δ61–87)B], and 3AB protein lacking amino acids 1 to 41 of 3A protein [3A(Δ1–41)B]. An siRNA library targeting human membrane-trafficking genes (total, 140 genes) was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific as a form of siGENOME Smart pools, which contain four sets of different siRNAs for each mRNA and were validated of over 75% knockdown efficiency of target mRNAs. As control siRNAs, siGLO Cyclophilin B control siRNA, siGLO Lamin A/C control siRNA, siGENOME Nontargeting siRNA 1 and 2, siGENOME RISC-Free control siRNA, and siGENOME Tox transfection control were used in each experiment. EerI was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

siRNA screening.

Duplex RNA of each siRNA (at a final concentration of 50 nM) was transfected into HEK293 cells (5.0 × 103 cells in 100 μl medium per well) in 96-well plates (White Opaque Tissue Culture Plate, Becton Dickinson) by using DharmaFECT1 transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 h and then subjected to PV pseudovirus infection. Transfection efficiency of siRNA in the cells was evaluated by the efficiency of incorporation of fluorescence-labeled siRNA (siGLO control siRNAs) in the transfected cells at 24 h posttransfection (p.t.) and by the efficiency of cell death in the cells transfected with the siGENOME Tox transfection control at 96 h p.t. (Cells transfected with this control reagent die by apoptosis.) For analysis of expression levels of target proteins in siRNA-transfected cells, cell lysates of siRNA-transfected cells in a well of 24-well plates were prepared at 72 h p.t. in 100 μl of cell lysis buffer (21 mM HEPES buffer [pH 7.4], 1.8 mM disodium hydrogen phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 5 mM EDTA, supplemented with a Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablet [Roche]) and then subjected to Western blot analysis.

At 72 h p.t., siRNA-transfected cells were inoculated with 800 IU of PV pseudovirus in a total of 200 μl per well at 96 h p.t. of siRNAs. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 7 h, and then the luciferase activity in the cells was measured with a Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) using a 2030 ARVO X luminometer (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mean number of net relative light units (RLU) detected in mock-treated cells was around 1.4 × 104 RLU, with standard deviations of 15% of the mean. PV pseudovirus infection in siRNA-transfected cells was calculated as a percentage of luciferase activity of the infected cells, where the luciferase activity in mock-transfected cells in the absence of compounds was taken as 100%. To evaluate the direct effect of siRNA treatment, net PV pseudovirus infection, which is a ratio of percent PV pseudovirus infection in siRNA-transfected cells to percent cell viability, was determined for each siRNA treatment. Net PV pseudovirus infection in mock-transfected cells was 1.

Rescue of PV replication in VCP-knockdown cells by mutant VCP expression.

HEK293 cells transfected with siRNA targeting VCP (VCP-siRNA) or mock-transfected cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding EGFP-fused VCP mutants derived from mouse VCP (59) or EGFP (control) by using a Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) at 48 h after siRNA transfection. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h after DNA transfection. RNA transcripts of the PV replicon were obtained by using a RiboMAX Large-Scale RNA Production System-T7 kit (Promega) with DraI-linearized DNA of pPV-Fluc mc, which encodes a PV replicon based on PV1 (Mahoney) with a firefly luciferase gene instead of the capsid-coding region, as the template. RNA transcripts were transfected into the cells by using a Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested at 7 h p.t. of the RNA transcripts, and then luciferase activity in the cells was measured with a Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) using a 2030 ARVO X luminometer (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and then blocked with 0.1% Triton–3% FCS–HBS (21 mM HEPES buffer [pH 7.4], 1.8 mM disodium hydrogen phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl). The cells were stained by indirect immunofluorescence with primary antibodies against FLAG (mouse antibody 2H8; TransGenic Inc.), VCP (mouse and rabbit antibody; Abcam), GBF1 (mouse antibody [BD Transduction Laboratory] and rabbit antibody [Abcam]), PI4KB (mouse antibody [BD Transduction Laboratory] and rabbit antibody [Millipore]), double-stranded RNA ([dsRNA] English & Scientific Consulting Bt), PV 3A (rabbit antibody), PV 3B (rabbit antibody), secondary antibodies (anti-mouse or anti-rabbit goat antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, 594, and 350 dyes [Molecular Probes]), and Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) for counterstaining of nuclei (2). For double staining of GBF1 and 3A, cells were blocked with anti-rabbit goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) after GBF1 staining and before staining against 3A protein. For labeling of nascent viral RNA, PV-infected cells were treated with 10 μg/ml of actinomycin D at 3 h postinfection (p.i.) for 1 h and then were transfected with bromouridine triphosphate (BrUTP) by using TransIT-293 transfection reagent (Mirus). The cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min and then stained with anti-bromodeoxyuridine antibody (Roche), followed by anti-mouse goat antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes). Samples were observed with a confocal scanning laser microscope (FV1000; Olympus).

Immunoprecipitation.

pKS435-3AB-His, -2BC-His, and -2C-His, with FLAG-VCP, VCP-GFP-FLAG, or VCP-GFP (without the FLAG tag), expression vectors were transfected into HEK293 cells cultured on a six-well plate using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. At 48 h p.t., cells were washed twice with DMEM, and then cytosolic protein fractions were prepared by using a ProteoExtract Transmembrane Protein Extraction Kit (Novagen). Cytosolic protein fractions were mixed with 20 μl of prewashed anti-FLAG magnetic beads (anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads; Sigma-Aldrich) and then incubated for 1 h on a rotator at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with washing buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 137 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM MgCl2) and then boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-His tag antibody (Penta-His HRP Conjugate; Qiagen) (for detection of 3AB-His, 2BC-His, and 2C-His) and anti-VCP antibody (for detection of FLAG-tagged VCPs and endogenous VCP).

Western blot analysis.

Samples were subjected to 5 to 20% gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (e-PAGEL; Atto Corporation) in a Laemmli buffer system (57). The proteins in the gel were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride filter (Immobilon; Millipore) and blocked by using a blocking reagent (Qiagen). The filters were incubated with anti-His tag antibody (Penta-His HRP Conjugate; Qiagen), anti-FLAG tag antibody (anti-FLAG M2-peroxidase antibody; Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse anti-VCP antibody (Abcam) (at 1:1,000, 1:300, and 1:3,000) in a SNAP i.d. System (Millipore). The filters were washed with phosphate-buffered saline ([PBS] 10 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.0], 135 mM NaCl, and 2.6 mM KCl) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) three times. For detection with anti-VCP antibody, the filters were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase ([HRP] 1:1,000 dilution; Pierce). The filters were washed by PBS-T three times and then treated with SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce) for the detection of the signal.

Mammalian two-hybrid assays.

The mammalian two-hybrid assays were performed as described previously using a Checkmate mammalian two-hybrid system (Promega) (46, 85). VCP and PV proteins (2B, 2BC, 2C, 3A, and 3AB) were expressed as fusion proteins in pFN10A(ACT) Flexi vector (pACT-VCP, PV-2B, PV-2BC, PV-2C, PV-3A, and PV-3AB) and pFN10A(BIND) Flexi vector (pBIND-VCP, PV-2B, PV-2BC, PV-2C, PV-3A, and PV-3AB). pACT-VCP and pBIND-VCP were cotransfected with pBIND-PV protein expression vectors and pACT-PV protein expression vectors, respectively, with a reporter plasmid (pGL4.31[luc2P/GAL4 UAS/Hygro]) into HEK293 cells. pACT and pBIND empty vectors were used with pBIND-VCP and pACT-VCP as controls, respectively. Firefly luciferase activity (derived from a reporter plasmid produced by binding of fusion proteins) and Renilla luciferase activity (derived from pBIND vectors for normalization of transfection efficiency) were measured at 24 h p.t. of DNA. The ratio of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase was calculated and then normalized by the ratio of the controls.

PLA.

A proximity ligation assay (PLA) was performed by using Duolink II reagents (Olink Bioscience). HEK293 cells expressing 3AB or 2BC proteins were fixed and permeabilized as described in indirect immunofluorescence and then incubated with antibodies. For detection of PLA signals, anti-3B or -2C antibodies (rabbit antibodies) were used with anti-VCP antibody (mouse antibody) (for detecting PLA signal between 3AB/2BC and VCP), and the individual antibody (anti-3B, -2C or -VCP antibody) was used as a negative control in the PLA. After the PLA, cells were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence to detect 3AB, 2BC, and VCP in the cells with secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse goat antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488). Samples were observed with a confocal scanning laser microscope (FV1000; Olympus).

Isolation of PV mutants resistant to VCP knockdown.

VCP siRNA-transfected HEK293 cells in 96-well plates were infected with PV1 (Mahoney) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 or 1 at 72 h p.t. of VCP siRNA. The cells were incubated at 37°C and then collected at day 2 p.i. Collected cell lysates were mixed and then used for the next passage. The resistance phenotype of the virus was observed by the appearance of cytopathic effect (CPE) after four passages. Resistant mutants were isolated by limiting dilution, and then the structural and nonstructural protein-encoding regions of the viral genomes were analyzed as previously described (8).

Gaussia luciferase secretion assay.

VCP-, GBF1-, and PI4KB-siRNA- or mock-transfected HEK293 cells in 96-well plates were transfected with 0.2 μg per well of expression vectors encoding PV 2B, 2BC, 3A, and 3AB or EGFP (control vector) and 0.002 μg per well of pTK-Gluc vector encoding Gaussia luciferase by using a Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) at 48 h p.t. of siRNA. Supernatants of transfected cells were collected at 20 h p.t. of DNA, and then the luciferase activity in the supernatants was measured with a BioLux Gaussia Luciferase Assay kit (New England BioLabs, Inc.) using a 2030 ARVO X luminometer (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis.

The results of experiments are shown as the averages with standard deviations. The effect of siRNA treatment on PV infection was analyzed by a t test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant and are indicated by asterisks in the figures.

RESULTS

siRNA screening targeting membrane-trafficking genes for host factors required for PV replication.

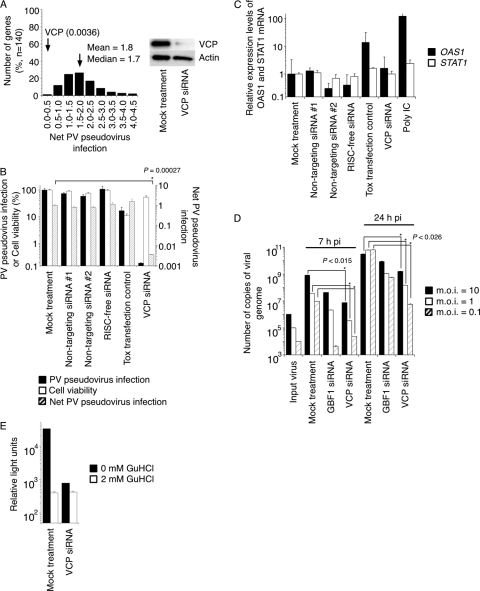

We performed screening with an siRNA library targeting 140 membrane-trafficking genes for host factors required for PV infection by using a PV pseudovirus infection system (4, 7). A summary of the results of the screening is shown in Fig. 1A and in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The mean and median net PV pseudovirus infection values of the siRNA screening were 1.9, and 1.7, respectively. siRNA targeting VCP showed the highest inhibitory effect on PV pseudovirus infection (net PV pseudovirus infection of 0.0036) among the examined siRNAs (Fig. 1B). An interferon (IFN) response, which could be induced by siRNA treatment (78), was not observed in the cells treated with an siRNA targeting VCP (Fig. 1C). We analyzed the inhibitory effect of an siRNA targeting VCP, along with one that targets a PV host factor, GBF1 (91), on PV infection (Fig. 1D). The copy number of viral RNA of PV1 (Mahoney) in the cells treated with an siRNA targeting VCP was about 1/100 of that in mock-treated cells at 7 h p.i., suggesting a high inhibitory effect of the siRNA targeting VCP as well as that of the siRNA targeting GBF1. Viral protein synthesis in VCP-siRNA-treated cells was measured in the presence of the PV replication inhibitor GuHCl. The level of viral protein synthesis in VCP-siRNA-treated cells was similar to that in mock-treated cells in the presence of GuHCl (Fig. 1E). These results suggested that VCP is a host factor for PV replication required after viral protein synthesis.

Fig 1.

Screening of an siRNA library targeting membrane-trafficking genes for host factors of PV infection. (A) Screening of an siRNA library targeting membrane-trafficking genes. The left panel shows distribution of net PV pseudovirus infection values of siRNAs targeting 140 genes. The distribution of the numbers of genes in each range of net PV infection values is shown. Cells transfected with VCP-siRNAs showed the highest inhibitory effect on PV pseudovirus infection (0.0036 of net PV pseudovirus infection). The right panel shows Western blot analysis of VCP expression in cells treated with VCP-siRNA. (B) Inhibitory effect of VCP-siRNA treatment on PV pseudovirus infection. PV pseudovirus infection, cell viability, and net PV pseudovirus infection in siRNA-transfected cells are shown. (C) Interferon response to siRNA treatment. Expression levels of mRNAs of OAS1 and STAT1 in siRNA-transfected cells are shown. (D) Inhibitory effect of siRNA treatment targeting VCP and GBF1 on PV1 (Mahoney) infection. Cells were infected with PV1 (Mahoney) at an MOI of 10, 1, or 0.1, and then the amounts of viral genome in the cells were analyzed at 7 or 24 h p.i. Numbers of copies of viral genome of input virus and in infected cells are shown. (E) Viral protein synthesis in VCP-knockdown cells. Mock- and VCP-siRNA-treated cells (1.0 × 104 cells) were infected with PV pseudovirus (6.5 × 105 IU) in the presence (2 mM) or absence of GuHCl. Luciferase activities in the cells at 2 h p.i. are shown.

VCP colocalizes with viral 2BC/2C and 3AB/3B proteins and interacts with 2BC and 3AB proteins.

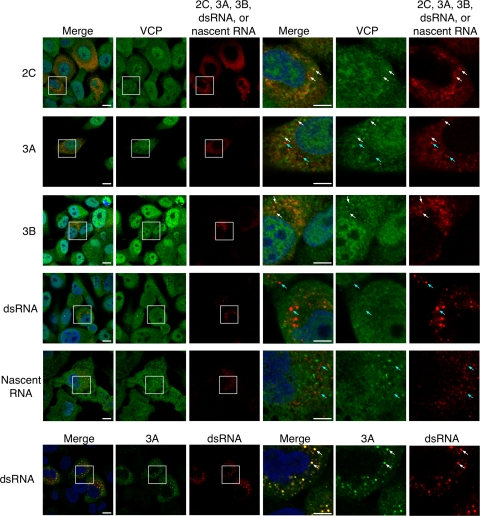

To analyze involvement of VCP in PV replication, we analyzed colocalization of VCP with viral proteins in PV-infected cells. We analyzed colocalization of VCP with viral proteins 2BC/2C, 3A/3AB, 3AB/3B, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), and nascent viral RNA (Fig. 2). VCP was observed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of mock-infected cells (65) and showed a partial accumulation in the cytoplasm after PV infection (data not shown). In high-resolution images, VCP appeared as a small dot-like structure in PV-infected cells and colocalized with viral proteins 2BC/2C and 3AB/3B. 3A and dsRNA colocalized in PV-infected cells but not with VCP. VCP also did not show colocalization with nascent viral RNA. We also analyzed localization of PI4KB and GBF1 in PV-infected cells (Fig. 3). 2BC/2C and 3AB/3B colocalized with PI4KB and GBF1; however, colocalization of dsRNA was observed only with PI4KB and not with GBF1 and VCP.

Fig 2.

Localization of viral proteins, viral RNAs, and VCP in PV-infected RD cells. The first five rows show indirect immunofluorescence of viral proteins 2C, 3A, 3B, dsRNA, and VCP (nascent RNA) in PV-infected cells at 4 h p.i. The three right-most columns show magnified views of the boxed areas in the first three columns. Blue, nucleus (staining with Hoechst 33342); green, VCP; red, 2C, 3A, 3B, dsRNA, or nascent viral RNA. Scale bars, 10 μm (first three columns) and 5 μm (three right-most columns). The bottom row shows indirect immunofluorescence images of viral proteins 3A and dsRNA in PV-infected cells. The columns are as described above. Blue, nucleus (staining with Hoechst 33342); green, 3A; red, dsRNA. Scale bars, 10 μm (first three panels) and 5 μm (three right-most panels). White arrows indicate some of the colocalized sites, and cyan arrows indicate some of the noncolocalized sites.

Fig 3.

Localization of viral proteins, viral RNAs, and PI4KB and GBF1 in PV-infected RD cells. Indirect immunofluorescence images of PI4KB (A) or GBF1 (B) are shown. The three right-most columns are magnified views of the boxed areas in the first three columns. Blue, nucleus (staining with Hoechst 33342); green, PI4KB or GBF1; red, 2C, 3A, 3B, or dsRNA. Scale bars, 10 μm (first three columns) and 5 μm (three right-most columns). White arrows indicate some of the colocalized sites, and cyan arrows indicated some of the noncolocalized sites.

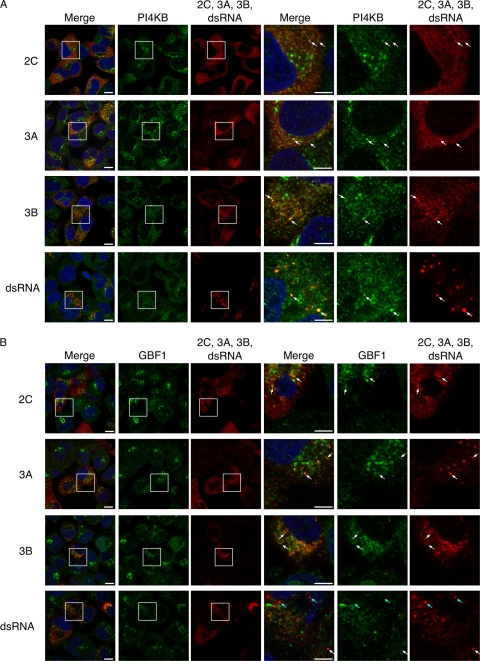

Next, we analyzed localization of VCP in cells transiently overexpressing individual viral proteins 2BC, 2C, 3A, and 3AB (Fig. 4A). VCP showed complete colocalization with 2BC and 3AB and partial colocalization with 2C and 3A. Overexpression of 3A caused drastic relocalization of VCP in the cytoplasm to form vesicle-like structures, previously observed as swelling of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in 3A-expressing cells (33), but only partial colocalization with VCP was observed. 3AB localized in perinuclear regions of transfected cells, consistent with a previous observation (29), and showed complete colocalization with VCP. To determine the region of 3AB responsible for VCP interaction, we analyzed colocalization of VCP with deletion mutants of 3AB. We found that the deletion mutant 3A(Δ1–41)B, which lacks aa 1 to 41 of 3A including residues involved in 3A dimerization (aa 25 to 43) (81), appeared as a small dot-like structure in the cytoplasm and colocalized with VCP. GBF1 and PI4KB colocalized with 3AB and VCP but not with the deletion mutant 3A(Δ1–41)B (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Localization of overexpressed viral proteins with VCP. (A) Localization of VCP in HEK293 cells expressing 2C, 2BC, 3A, and 3AB mutants. Blue, nucleus (staining with Hoechst 33342); green, VCP; red, 2C, 2BC, 3A, 3AB, or a 3AB mutant. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Mammalian two-hybrid assay for VCP and PV proteins. Closed bars, pACT-VCP and pBIND-PV proteins; open bars, pBIND-VCP and pACT-PV proteins. Normalized firefly luciferase activities are shown. (C) Immunoprecipitation of 3AB, 2BC, and 2C with VCP. HEK293 cells expressing 3AB, 2BC, or 2C (3AB-His, 2BC-His, or 2C-His) with FLAG-VCP, VCP-GFP-FLAG, or VCP-GFP were precipitated by anti-FLAG antibody. The amounts of VCP and viral proteins in input (4% of cell lysate used for immunoprecipitation) and pulldowns (immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-VCP antibody (for FLAG-VCP, VCP-GFP-FLAG, and VCP-GFP) or anti-Penta-His antibody (for 3AB-His, 2BC-His, and 2C-His). (D) PLA signals between viral proteins and VCP in 3AB- and 2BC-expressing cells. 3AB- and 2BC-expressing cells were incubated with anti-3B/2C antibodies with anti-VCP antibody (left six panels) or with individual antibodies (anti-3B/2C antibodies or anti-VCP antibody) and then subjected to PLA. Blue, nucleus (staining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole[DAPI]); green; 3AB or 2BC or VCP; red, PLA signals.

We analyzed the interaction of VCP with viral proteins by a mammalian two-hybrid assay (Fig. 4B). We found that only 2BC and not 2B, 2C, 3A, or 3AB showed an interaction with VCP in this assay. The interaction of VCP with 3AB and 2BC, but not with 2C, was detected by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 4C), and the proximity of 3AB/2BC and VCP was detected by PLA (79) (Fig. 4D). This suggested that VCP interacts with viral proteins 2BC and 3AB by a mode that differs from that of GBF1 and PI4KB.

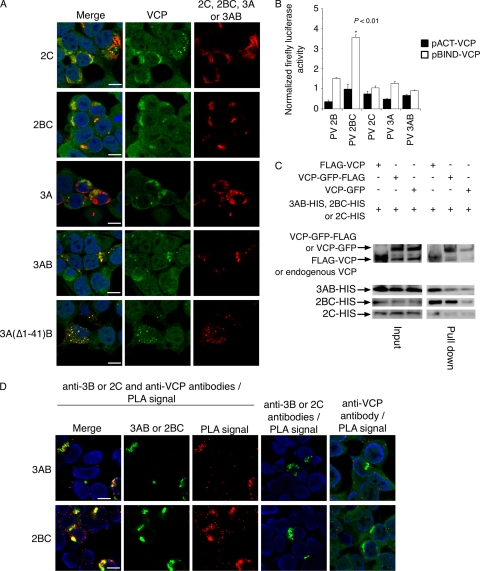

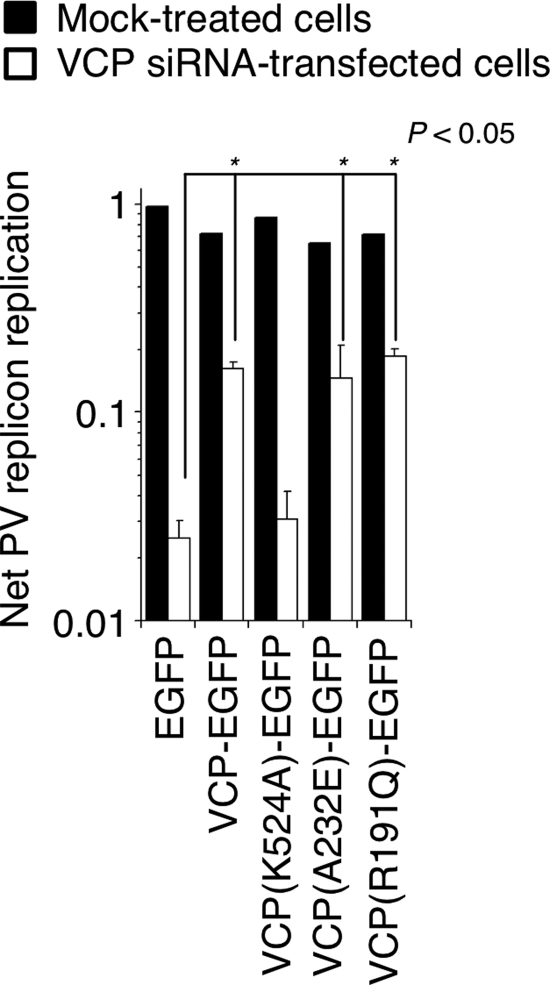

ATPase activity of VCP is essential for PV replication.

To determine the importance of the biological function of VCP in PV replication, we analyzed VCP mutants with different levels of ATPase activities; two mutants with increased ATPase activity [VCP(A232E) and VCP(R191Q)] (38, 59) and a mutant deficient in ATPase activity [VCP(K524A)] (55) were used. The transfection efficiency of VCP mutants was more than 80% as observed by EGFP tag expression; however, expression of none of the VCP mutants affected PV replicon replication (Fig. 5). This suggested that a dominant negative effect of VCP(K524A) was not observed in PV infection. We reasoned that endogenous VCP, which is an abundant ATPase comprising 14% of the amount of actin or 0.7% of total cytoplasmic proteins (65), might serve as a host factor for PV replication even in the presence of a dominant negative VCP mutant. Therefore, we analyzed the effect of VCP mutants on PV replication in cells depleted of endogenous VCP with an siRNA treatment targeting VCP. VCP mutants used for expression experiments were derived from a mouse VCP orthologue (59), which has 100% amino acid similarity to human VCP but is resistant to an siRNA targeting human VCP, for mutations in the target sites of the siRNA. In VCP-knockdown cells, only VCP mutants with ATPase activity rescued PV replication (Fig. 5). This suggested that the ATPase activity of VCP is essential for PV replication irrespective of the levels of ATPase activity and that the inhibitory effect of VCP-siRNA on PV replication was caused by the depletion of VCP and not by the off-target effect of siRNA.

Fig 5.

Role of ATPase activity of VCP in PV replication. PV replicon replication was analyzed in mock-treated and VCP-siRNA-transfected HEK293 cells expressing EGFP (control) or VCP mutants. A t test was performed for the net PV replicon replication between EGFP-expressing cells (control) and cells expressing each of the VCP mutants.

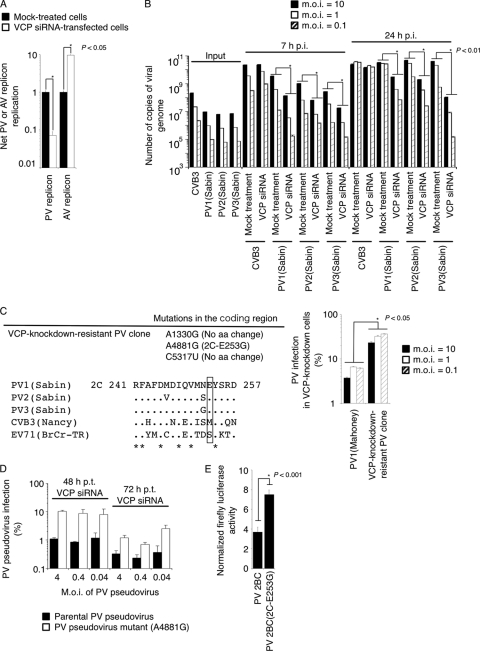

Knockdown of VCP suppressed PV infection but not CVB3 infection and enhanced AV replication.

To analyze the effect of VCP knockdown on the replication of picornavirus, we first analyzed AV replication in VCP-knockdown cells (Fig. 6). AV is a member of the genus Kobuvirus of the family Picornaviridae (97). Knockdown of VCP significantly suppressed replication of the PV replicon but enhanced the replication of the AV replicon (about a 9-fold increase) (Fig. 6A). Next, we analyzed the infection of CVB3, which belongs to another EV species, Human enterovirus B, in VCP-knockdown cells (Fig. 6B). The titers of type 1, 2, and 3 PV (Sabin), but not of CVB3, were reduced in VCP-knockdown cells at both 7 h p.i. and 24 h p.i. These results suggested that the effect of VCP knockdown on viral replication is different among members of the picornavirus family.

Fig 6.

VCP act as a PV-specific host factor of viral replication via a cellular secretion pathway. (A) Effect of VCP-siRNA treatment on PV and AV replicon replication. Luciferase activity in mock-treated and VCP-siRNA-transfected cells was analyzed at 7 h p.t. of RNA transcripts of each replicon. (B) Effect of VCP-siRNA treatment on CVB3 and type 1, 2, and 3 PV infection. Cells were infected with CVB3 or type 1, 2, and 3 PV (Sabin) at an MOI of 10, 1, or 0.1, and then the amounts of viral genome in the infected cells were analyzed at 7 or 24 h p.i. Numbers of copies of the viral genome of input virus and in infected cells are shown. The number of copies of the viral genome in VCP-siRNA-treated cells was compared with that in mock-treated cells infected with viruses at each MOI. (C) Isolation of PV mutant resistant to VCP knockdown. The left panel shows mutations in the coding region of a VCP-knockdown-resistant PV clone (top) and partial 2C sequences around aa 253 (aa 241 to 257 of 2C) of enteroviruses (bottom) are shown. Amino acid 253 is highlighted in a rectangle. Results of a PV infection assay in VCP-knockdown cells are shown at right. VCP-siRNA-transfected or mock-treated HEK293 cells were infected with PV1 (Mahoney) or a VCP-knockdown-resistant PV clone at 48 h p.t. of VCP siRNA at an MOI of 10, 1, and 0.1. Numbers of copies of viral RNA were determined at 7 h p.i. PV infection in VCP-knockdown cells is presented as a percentage of the number of copies of viral RNA in VCP-siRNA-transfected cells compared to that in mock-treated cells (100%). A t test was performed between samples for each MOI. (D) Effect of VCP-siRNA treatment on PV pseudovirus infection with an A4881G mutation. VCP-siRNA-transfected HEK293 cells were infected with a parental PV pseudovirus or a PV pseudovirus mutant with an A4881G mutation at an MOI of 4, 0.4, or 0.04 at 48 or 72 h p.t. of VCP-siRNA. Percent PV pseudovirus infection is shown. (E) Mammalian two-hybrid assay for VCP (pBIND-VCP) and PV proteins [pACT-PV 2BC or PV 2BC(2C-E253G)]. Normalized firefly luciferase activities are shown.

VCP acts as a host factor of PV replication via a cellular secretion pathway.

Next, we attempted to isolate a resistant PV mutant that could show efficient infection in VCP-knockdown cells. We repeated passage of PV1 (Mahoney) in VCP-knockdown cells, and we observed a clear CPE in the infected cells after five passages, in contrast to inapparent and delayed CPE in parental PV1 (Mahoney)-infected cells. An isolated resistant clone showed improved growth in VCP-knockdown cells compared to the parental PV1 (Mahoney) strain (Fig. 6C, right panel). This clone had only one amino acid change in the viral proteins, a 2C-E253G mutation, which is known as the determinant of a PV mutant for a secretion inhibition-negative phenotype (19). Sequences of 2C around aa 253 are not conserved in picornaviruses but are conserved among PV strains. PV pseudovirus with an A4881G (2C-E253G) mutation showed a resistance phenotype in VCP-knockdown cells (Fig. 6D). The resistance phenotype is stronger in cells treated with VCP-siRNA for 48 h than that in cells treated for 72 h, suggesting that PV with a 2C-E253G mutation retained dependency on VCP for its replication. The effect of the 2C-E253G mutation on 2BC binding to VCP was evaluated with a mammalian two-hybrid assay (Fig. 6E). Consistent with the above observation, increased luciferase signals were detected for 2BC with a 2C-E253G mutation [2BC(2C-E253G)] with VCP, suggesting an increased affinity between 2BC and VCP by this mutation. These results suggested that VCP acts as a host factor of PV replication, possibly via a cellular secretion pathway.

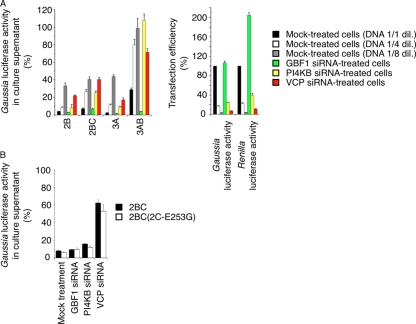

VCP is not required for inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of individual viral proteins.

To analyze the role of VCP in inhibition of cellular protein secretion by PV infection, we examined cellular protein secretion in VCP-siRNA-treated cells expressing each of the viral proteins 2B, 2BC, 3A, and 3AB (Fig. 7). We observed strong inhibition of the secretion of Gaussia luciferase caused by overexpression of 2B, 2BC, and 3A, consistent with a previous report (34), and also a weak inhibitory effect of 3AB. In PI4KB- and VCP-siRNA-treated cells, suppression of the inhibitory effect caused by viral proteins, including 2B, 2BC, 3A, and 3AB, was observed; however, the apparent inhibitory effect of each individual viral protein in this in vitro system depended on the transfection efficiency of DNA that was evaluated by Gaussia luciferase activity in the cell supernatants and by Renilla luciferase activity in the cells (Fig. 7A, right panel). The PI4KB- and VCP-siRNA treatments significantly reduced the DNA transfection efficiencies in the treated cells, and specific suppression effects beyond the reduced DNA transfection efficiency were not observed. In contrast, GBF1 knockdown enhanced the inhibitory effect of 3AB. We also analyzed the effect of a 2C-E253G mutation on the inhibitory effect of 2BC but could not detect a significant suppression of the inhibitory effect caused by 2BC with a 2C-E253G mutation (Fig. 7B). These results suggested that VCP did not suppress the inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of each individual viral protein.

Fig 7.

Effect of knockdown of VCP on the inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of each individual viral protein. (A) Inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by the individual viral protein in siRNA-treated cells. Secretion of Gaussia luciferase was analyzed in mock-treated and GBF1-, PI4KB-, and VCP-siRNA-transfected HEK293 cells expressing viral proteins 2B, 2BC, 3A, and 3AB (left). For mock-treated cells, DNAs (control vector and Gaussia luciferase expression vector) diluted by 1-, 4-, and 8-fold were transfected to control the transfection efficiency. Gaussia luciferase activity in cells transfected with a control expression vector was taken as 100%. At right is an evaluation of DNA transfection efficiency. Gaussia luciferase activity in the cells transfected with a control vector and Gaussia luciferase expression vector and Renilla luciferase activity in the cells transfected with Renilla luciferase expression vector are shown as percentages. (B) Effect of a 2C-E253G mutation on the inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of 2BC protein in siRNA-treated cells. Gaussia luciferase activity was determined in siRNA-transfected cells, with the value for cells transfected with a control expression vector taken as 100%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified VCP as a host factor required for PV replication by siRNA screening targeting membrane-trafficking genes. Important host factors involved in virus replication have been identified in this pathway of genes, including PI4KA, which showed the highest inhibitory effect on hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication in siRNA screening (14). VCP was originally identified as the protein that contains the amino acids of valosin peptide, which was considered a physiologically active peptide but turned out to be an artifact by the analysis of amino acid sequence of VCP (56). Analysis of VCP showed that VCP belongs to the class I AAA+ family (92) and has roles in a variety of cellular processes, including protein degradation pathways (64, 69, 95), homotypic membrane fusions (i.e., Golgi reassembly [68], transitional ER reassembly [71], and nuclear envelope assembly [41]). Mutations of VCP cause a dominantly inherited disorder, inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia (IBMPFD) (76, 88), possibly by interfering with the ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation pathway (e.g., immature autophagosome formation) (50, 52, 87) by enhancing ATPase activity of VCP (38, 59). In PV replication, VCP targeted the replication step after viral protein synthesis, and ATPase activity of VCP was essential irrespective of the levels of activity of the VCP mutants examined (Fig. 1E and 5). VCP mutants with IBMPFD mutations or with an ATPase activity-deficient mutation (K524A) are known to interfere with clearance of ubiquitinated proteins because of impaired aggresome formation (51, 53, 54, 89, 90, 96). Our observations suggested that some level of ATPase activity of VCP is sufficient to support PV replication and that fine-tuned ATPase activity required for normal ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation is not necessary for PV replication.

In PV-infected cells, VCP colocalized with viral proteins 2BC/2C and 3AB/3B but not with 3A, dsRNA, or nascent viral RNA (Fig. 2). 2BC/2C and 3AB/3B also colocalized with PI4KB and GBF1 in PV-infected cells (Fig. 3). However, colocalization of dsRNA was observed only with PI4KB and not with GBF1 and VCP. This may suggest a functional difference of these 3A/3AB-binding proteins that share colocalization with viral proteins. In cells transiently overexpressing viral proteins, 2BC and 3AB showed clear colocalization with VCP (Fig. 4A), consistent with the observations in PV-infected cells. Although VCP has a role in autophagosome formation, the localization of VCP in PV-infected cells seems different from that of the autophagosome marker protein LC3, which showed clear colocalization with 3A in PV-infected cells (48). We observed colocalization of 3A with dsRNA and PI4KB, but not with VCP, in PV-infected cells (Fig. 2 and 3). This suggested that VCP might not be directly involved in autophagosome formation in PV replication or have only a temporal role in autophagosome formation. VCP interacted with the C-terminal region of 3AB (aa 42 to 87 of 3A) in contrast to GBF1 and PI4KB, which interacted with 3AB via the N-terminal region of 3A (aa 1 to 41 of 3A) (Fig. 4B) (33, 43, 86, 91). This suggested that the interaction of VCP with 3AB occurs independently of that of GBF1/PI4KB. Interestingly, the effect of VCP knockdown on viral replication is different among the picornaviruses, with strong suppression for PV, apparently no effect for CVB3, and enhancement for AV (Fig. 6A and B). This observation might suggest some alternative/opposite pathways used for replication of these viruses or a difference in the expression levels of VCP required for optimal replication of these viruses. Interestingly, a VCP orthologue has been identified as a host factor required for the infection of Drosophila C virus, which belongs to Dicistroviridae, in an siRNA screening (22). This might provide a marked contrast to the broad spectrum of GBF1 and PI4KB as host factors in picornaviruses. GBF1 also could act as a host factor for HCV, a member of the Flaviviridae (36), and PI4KA might play the corresponding role of PI4KB in HCV replication for recruitment of viral polymerase (14, 43). These observations suggested that VCP and GBF1/PI4KB have different roles in PV replication via their interactions with 2BC/3AB and 3A/3AB, respectively.

To further analyze the function of VCP in PV replication, we isolated a PV mutant resistant to VCP knockdown (Fig. 6C). The isolated mutant had the mutation A4881G (2C-E253G), which is known as a determinant of a secretion inhibition-negative phenotype of PV (19), as the determinant of the resistance phenotype. The resistance phenotype of this PV mutant was weaker in cells treated by VCP-siRNA for 72 h than that observed in cells treated for 48 h (Fig. 6D), suggesting that VCP is required even for the replication of this VCP-knockdown-resistant PV mutant. Consistent with this observation, increased affinity between 2BC and VCP was observed with a 2C-E253G mutation (Fig. 6E). This might have an analogy with a BFA-resistant PV mutant, which retained dependency on GBF1 for its replication (13). A PV mutant with a 2C-E253G mutation was originally identified by selecting PV-infected cells that expressed newly synthesized surface proteins by using cell sorting (19). However, the origin of the selection pressure or responsible host factors for the emergence of this secretion inhibition-negative mutant remained to be identified. Our results suggested a positive role of VCP in inhibition of cellular protein secretion in PV-infected cells and enhancement of viral RNA replication that might have acted as the selection pressure on the emergence of a secretion inhibition-negative PV mutant. The positive role of VCP in cellular protein secretion was not detected with an ATPase activity-deficient VCP mutant that did not affect Golgi structure or cellular protein secretion but caused an accumulation of ubiquitinated protein degradation in the ER and ER swelling (28). We could not observe the positive involvement of VCP in the inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of the viral proteins 2B, 2BC, 3A, and 3AB (Fig. 7). To date, overexpression analysis of viral proteins identified 2B/2BC and 3A as the viral proteins responsible for cellular protein secretion (34), and analysis of PV mutants with the secretion-inhibition-negative phenotype identified 2C and 3A as the determinants of the phenotype (15, 19, 32). Our result suggested that VCP acted as a selection pressure on PV for the secretion inhibition-negative phenotype in the infection but was not involved in the inhibition of cellular protein secretion caused by overexpression of individual viral proteins.

VCP colocalizes with ubiquitin-positive inclusions known as aggresomes in various neurodegenerative diseases, including polyglutamine diseases (42, 45, 61), and are involved in aggresome formation and clearance of the aggregate (49, 53, 54, 96). Aggresome formation plays diverse roles in virus infection, including virus factory formation, replication, and packaging of DNA viruses (reviewed in reference 94; 39, 58).The role of VCP in PV replication, possibly via the VCP/3AB/2BC protein complex, remains to be further elucidated.

In summary, we identified VCP as a host factor required for viral RNA replication of PV among membrane-trafficking proteins and found that VCP acted as a selection pressure on PV for the secretion inhibition-negative phenotype. VCP could provide a novel link between the cellular protein secretion pathway and PV replication.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Junko Wada for her excellent technical assistance. We appreciate Akira Kakizuka and Seiji Hori for kindly providing us expression vectors for VCP mutants with helpful suggestions. We appreciate Jun Sasaki for kindly providing us a cDNA clone of AV replicon. We appreciate Takashi Shimoike for kind help in immunofluorescence microscopy.

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for the Promotion of Polio Eradication and Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan, and by a grant from the World Health Organization for a collaborative research project of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 February 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arita M, Ami Y, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2008. Cooperative effect of the attenuation determinants derived from poliovirus Sabin 1 strain is essential for attenuation of enterovirus 71 in the NOD/SCID mouse infection model. J. Virol. 82:1787–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arita M, Horie H, Arita M, Nomoto A. 1999. Interaction of poliovirus with its receptor affords a high level of infectivity to the virion in poliovirus infections mediated by the Fc receptor. J. Virol. 73:1066–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arita M, et al. 2011. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III beta is a target of enviroxime-like compounds for antipoliovirus activity. J. Virol. 85:2364–2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arita M, Nagata N, Sata T, Miyamura T, Shimizu H. 2006. Quantitative analysis of poliomyelitis-like paralysis in mice induced by a poliovirus replicon. J. Gen. Virol. 87:3317–3327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arita M, Takebe Y, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2010. A bifunctional anti-enterovirus compound that inhibits replication and early stage of enterovirus 71 infection. J. Gen. Virol. 91:2734–2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arita M, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2009. Cellular kinase inhibitors that suppress enterovirus replication have a conserved target in viral protein 3A similar to that of enviroxime. J. Gen. Virol. 90:1869–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arita M, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2008. Characterization of pharmacologically active compounds that inhibit poliovirus and enterovirus 71 infectivity. J. Gen. Virol. 89:2518–2530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arita M, et al. 2005. A Sabin 3-derived poliovirus recombinant contained a sequence homologous with indigenous human enterovirus species C in the viral polymerase coding region. J. Virol. 79:12650–12657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barnard DL. 2006. Current status of anti-picornavirus therapies. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12:1379–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barton DJ, Flanegan JB. 1997. Synchronous replication of poliovirus RNA: initiation of negative-strand RNA synthesis requires the guanidine-inhibited activity of protein 2C. J. Virol. 71:8482–8489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Belov GA, Feng Q, Nikovics K, Jackson CL, Ehrenfeld E. 2008. A critical role of a cellular membrane traffic protein in poliovirus RNA replication. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Belov GA, Habbersett C, Franco D, Ehrenfeld E. 2007. Activation of cellular Arf GTPases by poliovirus protein 3CD correlates with virus replication. J. Virol. 81:9259–9267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belov GA, Kovtunovych G, Jackson CL, Ehrenfeld E. 2010. Poliovirus replication requires the N-terminus but not the catalytic Sec7 domain of ArfGEF GBF1. Cell. Microbiol. 12:1463–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berger KL, et al. 2009. Roles for endocytic trafficking and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha in hepatitis C virus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:7577–7582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berstein HD, Baltimore D. 1988. Poliovirus mutant that contains a cold-sensitive defect in viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 62:2922–2928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bienz K, Egger D, Troxler M, Pasamontes L. 1990. Structural organization of poliovirus RNA replication is mediated by viral proteins of the P2 genomic region. J. Virol. 64:1156–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bodian D. 1949. Histopathologic basis of clinical findings in poliomyelitis. Am. J. Med. 6:563–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown-Augsburger P, et al. 1999. Evidence that enviroxime targets multiple components of the rhinovirus 14 replication complex. Arch. Virol. 144:1569–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgon TB, Jenkins JA, Deitz SB, Spagnolo JF, Kirkegaard K. 2009. Bypass suppression of small-plaque phenotypes by a mutation in poliovirus 2A that enhances apoptosis. J. Virol. 83:10129–10139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caliguiri LA, Tamm I. 1968. Action of guanidine on the replication of poliovirus RNA. Virology 35:408–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen TC, et al. 2008. Development of antiviral agents for enteroviruses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1169–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cherry S, et al. 2006. COPI activity coupled with fatty acid biosynthesis is required for viral replication. PLoS Pathog. 2:e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choe SS, Dodd DA, Kirkegaard K. 2005. Inhibition of cellular protein secretion by picornaviral 3A proteins. Virology 337:18–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collett MS, Neyts J, Modlin JF. 2008. A case for developing antiviral drugs against polio. Antiviral Res. 79:179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Committee on Development of a Polio Antiviral and Its Potential Role in Global Poliomyelitis Eradication, National Research Council 2006. Exploring the role of antiviral drugs in the eradication of polio: workshop report. National Academies Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 26. Couderc T, et al. 1989. Molecular pathogenesis of neural lesions induced by poliovirus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 70:2907–2918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cuconati A, Molla A, Wimmer E. 1998. Brefeldin A inhibits cell-free, de novo synthesis of poliovirus. J. Virol. 72:6456–6464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dalal S, Rosser MF, Cyr DM, Hanson PI. 2004. Distinct roles for the AAA ATPases NSF and p97 in the secretory pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:637–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Datta U, Dasgupta A. 1994. Expression and subcellular localization of poliovirus VPg-precursor protein 3AB in eukaryotic cells: evidence for glycosylation in vitro. J. Virol. 68:4468–4477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Palma AM, et al. 2008. The thiazolobenzimidazole TBZE-029 inhibits enterovirus replication by targeting a short region immediately downstream from motif C in the nonstructural protein 2C. J. Virol. 82:4720–4730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Palma AM, et al. 2009. Mutations in the nonstructural protein 3A confer resistance to the novel enterovirus replication inhibitor TTP-8307. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1850–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dodd DA, Giddings TH, Jr, Kirkegaard K. 2001. Poliovirus 3A protein limits interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and beta interferon secretion during viral infection. J. Virol. 75:8158–8165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doedens, Giddings TH, Jr, Kirkegaard K. 1997. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi traffic by poliovirus protein 3A: genetic and ultrastructural analysis. J. Virol. 71:9054–9064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Doedens JR, Kirkegaard K. 1995. Inhibition of cellular protein secretion by poliovirus proteins 2B and 3A. EMBO J. 14:894–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eggers HJ, Tamm I. 1961. Spectrum and characteristics of the virus inhibitory action of 2-(alpha-hydroxybenzyl)-benzimidazole. J. Exp. Med. 113:657–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goueslain L, et al. 2010. Identification of GBF1 as a cellular factor required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 84:773–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Greninger AL, Knudsen GM, Betegon M, Burlingame AL, Derisi JL. 18 January 2012. The 3A protein from multiple picornaviruses utilizes the Golgi adaptor protein ACBD3 to recruit PI4KIIIβ. J. Virol. 86:3605–3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Halawani D, et al. 2009. Hereditary inclusion body myopathy-linked p97/VCP mutations in the NH2 domain and the D1 ring modulate p97/VCP ATPase activity and D2 ring conformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:4484–4494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heath CM, Windsor M, Wileman T. 2001. Aggresomes resemble sites specialized for virus assembly. J. Cell Biol. 153:449–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Heinz BA, Vance LM. 1995. The antiviral compound enviroxime targets the 3A coding region of rhinovirus and poliovirus. J. Virol. 69:4189–4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hetzer M, et al. 2001. Distinct AAA-ATPase p97 complexes function in discrete steps of nuclear assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:1086–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hirabayashi M, et al. 2001. VCP/p97 in abnormal protein aggregates, cytoplasmic vacuoles, and cell death, phenotypes relevant to neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 8:977–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hsu NY, et al. 2010. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell 141:799–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Irurzun A, Perez L, Carrasco L. 1992. Involvement of membrane traffic in the replication of poliovirus genomes: effects of brefeldin A. Virology 191:166–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ishigaki S, et al. 2004. Physical and functional interaction between Dorfin and Valosin-containing protein that are colocalized in ubiquitylated inclusions in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51376–51385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ishikawa K, Sasaki J, Taniguchi K. 2010. Overall linkage map of the nonstructural proteins of Aichi virus. Virus Res. 147:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ishitsuka H, Ohsawa C, Ohiwa T, Umeda I, Suhara Y. 1982. Antipicornavirus flavone Ro 09-0179. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:611–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jackson WT, et al. 2005. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 3:e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Johnston JA, Ward CL, Kopito RR. 1998. Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143:1883–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ju JS, et al. 2009. Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J. Cell Biol. 187:875–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ju JS, Miller SE, Hanson PI, Weihl CC. 2008. Impaired protein aggregate handling and clearance underlie the pathogenesis of p97/VCP-associated disease. J. Biol. Chem. 283:30289–30299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ju JS, Weihl CC. 2010. p97/VCP at the intersection of the autophagy and the ubiquitin proteasome system. Autophagy 6:283–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kitami MI, et al. 2006. Dominant-negative effect of mutant valosin-containing protein in aggresome formation. FEBS Lett. 580:474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kobayashi T, Manno A, Kakizuka A. 2007. Involvement of valosin-containing protein (VCP)/p97 in the formation and clearance of abnormal protein aggregates. Genes Cells 12:889–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kobayashi T, Tanaka K, Inoue K, Kakizuka A. 2002. Functional ATPase activity of p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for the quality control of endoplasmic reticulum in neuronally differentiated mammalian PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47358–47365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koller KJ, Brownstein MJ. 1987. Use of a cDNA clone to identify a supposed precursor protein containing valosin. Nature 325:542–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu Y, Shevchenko A, Berk AJ. 2005. Adenovirus exploits the cellular aggresome response to accelerate inactivation of the MRN complex. J. Virol. 79:14004–14016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Manno A, Noguchi M, Fukushi J, Motohashi Y, Kakizuka A. 2010. Enhanced ATPase activities as a primary defect of mutant valosin-containing proteins that cause inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia. Genes Cells 15:911–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Maynell LA, Kirkegaard K, Klymkowsky MW. 1992. Inhibition of poliovirus RNA synthesis by brefeldin A. J. Virol. 66:1985–1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mizuno Y, Hori S, Kakizuka A, Okamoto K. 2003. Vacuole-creating protein in neurodegenerative diseases in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 343:77–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Moffat K, et al. 2005. Effects of foot-and-mouth disease virus nonstructural proteins on the structure and function of the early secretory pathway: 2BC but not 3A blocks endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport. J. Virol. 79:4382–4395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nagashima S, Sasaki J, Taniguchi K. 2003. Functional analysis of the stem-loop structures at the 5′ end of the Aichi virus genome. Virology 313:56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nowis D, McConnell E, Wojcik C. 2006. Destabilization of the VCP-Ufd1-Npl4 complex is associated with decreased levels of ERAD substrates. Exp. Cell Res. 312:2921–2932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peters JM, Walsh MJ, Franke WW. 1990. An abundant and ubiquitous homo-oligomeric ring-shaped ATPase particle related to the putative vesicle fusion proteins Sec18p and NSF. EMBO J. 9:1757–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Peyroche A, et al. 1999. Brefeldin A acts to stabilize an abortive ARF-GDP-Sec7 domain protein complex: involvement of specific residues of the Sec7 domain. Mol. Cell 3:275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pierini R, Cottam E, Roberts R, Wileman T. 2009. Modulation of membrane traffic between endoplasmic reticulum, ERGIC and Golgi to generate compartments for the replication of bacteria and viruses. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:828–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rabouille C, Levine TP, Peters JM, Warren G. 1995. An NSF-like ATPase, p97, and NSF mediate cisternal regrowth from mitotic Golgi fragments. Cell 82:905–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ramadan K, et al. 2007. Cdc48/p97 promotes reformation of the nucleus by extracting the kinase Aurora B from chromatin. Nature 450:1258–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rotbart HA. 2002. Treatment of picornavirus infections. Antiviral Res. 53:83–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Roy L, et al. 2000. Role of p97 and syntaxin 5 in the assembly of transitional endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:2529–2542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sabin AB. 1965. Oral poliovirus vaccine. History of its development and prospects for eradication of poliomyelitis. JAMA 194:872–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Salk JE, et al. 1954. Studies in human subjects on active immunization against poliomyelitis. II. A practical means for inducing and maintaining antibody formation. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 44:994–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sandoval IV, Carrasco L. 1997. Poliovirus infection and expression of the poliovirus protein 2B provoke the disassembly of the Golgi complex, the organelle target for the antipoliovirus drug Ro-090179. J. Virol. 71:4679–4693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sasaki J, Ishikawa K, Arita M, Taniguchi K. 2012. ACBD3-mediated recruitment of PI4KB to picornavirus RNA replication sites. EMBO J. 31:754–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schroder R, et al. 2005. Mutant valosin-containing protein causes a novel type of frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 57:457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shimizu H, et al. 2000. Mutations in the 2C region of poliovirus responsible for altered sensitivity to benzimidazole derivatives. J. Virol. 74:4146–4154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sledz CA, Holko M, de Veer MJ, Silverman RH, Williams BR. 2003. Activation of the interferon system by short-interfering RNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:834–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Soderberg O, et al. 2006. Direct observation of individual endogenous protein complexes in situ by proximity ligation. Nat. Methods 3:995–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sohda M, et al. 2001. Identification and characterization of a novel Golgi protein, GCP60, that interacts with the integral membrane protein giantin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45298–45306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Strauss DM, Glustrom LW, Wuttke DS. 2003. Towards an understanding of the poliovirus replication complex: the solution structure of the soluble domain of the poliovirus 3A protein. J. Mol. Biol. 330:225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Suhy DA, Giddings TH, Jr, Kirkegaard K. 2000. Remodeling the endoplasmic reticulum by poliovirus infection and by individual viral proteins: an autophagy-like origin for virus-induced vesicles. J. Virol. 74:8953–8965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tang WF, et al. 2007. Reticulon 3 binds the 2C protein of enterovirus 71 and is required for viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 282:5888–5898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Taylor MP, Burgon TB, Kirkegaard K, Jackson WT. 2009. Role of microtubules in extracellular release of poliovirus. J. Virol. 83:6599–6609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Teterina NL, et al. 2006. Evidence for functional protein interactions required for poliovirus RNA replication. J. Virol. 80:5327–5337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Teterina NL, Pinto Y, Weaver JD, Jensen KS, Ehrenfeld E. 2011. Analysis of poliovirus protein 3A interactions with viral and cellular proteins in infected cells. J. Virol. 85:4284–4296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tresse E, et al. 2010. VCP/p97 is essential for maturation of ubiquitin-containing autophagosomes and this function is impaired by mutations that cause IBMPFD. Autophagy 6:217–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Watts GD, et al. 2004. Inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia is caused by mutant valosin-containing protein. Nat. Genet. 36:377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Weihl CC, Dalal S, Pestronk A, Hanson PI. 2006. Inclusion body myopathy-associated mutations in p97/VCP impair endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15:189–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Weihl CC, Miller SE, Hanson PI, Pestronk A. 2007. Transgenic expression of inclusion body myopathy associated mutant p97/VCP causes weakness and ubiquitinated protein inclusions in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16:919–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wessels E, et al. 2006. A viral protein that blocks Arf1-mediated COP-I assembly by inhibiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Dev. Cell 11:191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. White SR, Lauring B. 2007. AAA+ ATPases: achieving diversity of function with conserved machinery. Traffic 8:1657–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wikel JH, et al. 1980. Synthesis of syn and anti isomers of 6-[[(hydroxyimino)phenyl]methyl]-1-[(1-methylethyl)sulfonyl]-1H-benzimidaz ol-2-amine. Inhibitors of rhinovirus multiplication. J. Med. Chem. 23:368–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wileman T. 2006. Aggresomes and autophagy generate sites for virus replication. Science 312:875–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wojcik C, et al. 2006. Valosin-containing protein (p97) is a regulator of endoplasmic reticulum stress and of the degradation of N-end rule and ubiquitin-fusion degradation pathway substrates in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:4606–4618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wojcik C, Yano M, DeMartino GN. 2004. RNA interference of valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97) reveals multiple cellular roles linked to ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent proteolysis. J. Cell Sci. 117:281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yamashita T, et al. 1998. Complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of Aichi virus, a distinct member of the Picornaviridae associated with acute gastroenteritis in humans. J. Virol. 72:8408–8412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.