Abstract

The liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein (LAP) isoform of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ) is shown to be a major activator of differentiation-dependent human papillomavirus (HPV) late gene expression, while the liver-enriched inhibitory protein (LIP) isoform negatively regulates late expression. In undifferentiated cells, LIPs act as dominant-negative repressors of late expression, and upon differentiation, LIP levels are significantly reduced, allowing LAP-mediated activation of the late promoter. Importantly, knockdown of C/EBPβ isoforms blocks activation of late gene expression from complete viral genomes upon differentiation.

TEXT

The productive life cycle of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) is dependent on epithelial differentiation and is regulated by cellular and viral factors (22, 24). High-risk HPVs infect cells in the basal layer that become exposed following microwounding of the epithelia. Upon entry, viral genomes are established in the nucleus as multicopy extrachromosomal elements or episomes with only low levels of expression of early viral proteins (22). In infected basal cells, viral replication occurs coordinately with cellular replication, and stable copy numbers are maintained. Upon differentiation, the expression of late viral proteins is induced in suprabasal cells coinciding with entry into the G2 and M phases and genome amplification (22, 30). This is followed by capsid protein synthesis, packaging of virions, and release of viral particles. The stable maintenance phase in undifferentiated infected basal cells and the productive phase in suprabasal cells are controlled through the expression of two major promoters referred to as the early and late viral promoters (22, 24). The early viral promoter is active in the lower epithelial layers, whereas the late HPV promoter is active only in suprabasal layers, leading to its characterization as differentiation dependent.

The major viral promoter active in undifferentiated cells directs initiation of transcription at sites in the upstream regulatory region (URR) adjacent to the start codon for E6. In HPV type 31, this major early HPV promoter is referred to as p97 or p99 whereas in HPV-18 it is called p105 (15, 17, 25). By the use of transient assays, HPV early promoters have been shown to be activated by a series of cellular factors such as SP1, AP-1, and Oct1 (1, 6, 8–10, 16, 18). In addition, HPV E2 transcription factors positively and negatively modulate the activity of the early promoter through E2 binding sites located in the URR (11, 22). In contrast, the differentiation-dependent late promoter initiates transcription at a series of heterogeneous sites that extend over at least 100 nucleotides (nt) in the middle of the E7 open reading frame (ORF) (10). In HPV-31, the late promoter is referred to as p742 (17), while it is called p670 in HPV-16 (15). Differentiation of HPV-positive keratinocytes alone has been shown to be sufficient to activate low levels of late transcription, while genome amplification increases the levels of late gene expression through increased template numbers (5, 28). In contrast to the information available about the regulators of the early promoter, significantly less is known about the transcription factors that control late gene expression. The cellular factors CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ), Oct-1, and YY1 have been reported to bind putative late promoter sequences, though how this results in differentiation-dependent activation is still unclear (19, 32).

One candidate for a major activator of HPV late expression is CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ), which is a member of the basic leucine zipper of transcription factors and a key regulator of cell growth and differentiation (26). The intronless gene that codes for C/EBPβ is transcribed into a single mRNA transcript that, through the usage of alternative start codons, gives rise to three isoforms: two full-length C/EBPβ proteins referred to as liver-enriched transcriptional activator proteins (LAP and LAP*) and a short repressive isoform termed liver-enriched inhibitory protein (LIP) (2, 12). LIP lacks the transactivating domains found in the N terminus of LAP and LAP* (referred to as LAP for convenience) and, as a result, is unable to recruit histone acetyltransferases to activate transcription. The LIP isoform does, however, contain the basic DNA binding domain and the leucine zipper required for dimerization. As a result, LIP-LAP heterodimers can bind to C/EBP consensus sites on promoters and can do so with greater affinity than the LAP-LAP dimer, thereby acting as dominant-negative repressors (12). Kukimoto et al. (19) used transient assays together with heterologous expression vectors and HPV-16 reporters to show that high levels of C/EBPβ full-length proteins could enhance late reporter activity in monolayer cultures. Additional studies, however, suggested that C/EBPβ transactivator levels did not change upon differentiation of HPV-positive cells, raising the issue of whether these factors actually had a role in regulating this differentiation-dependent promoter (32). In the present study, we investigated what role, if any, C/EBPβ isoforms LIP and LAP play in the differentiation-dependent regulation of HPV-31 late gene expression.

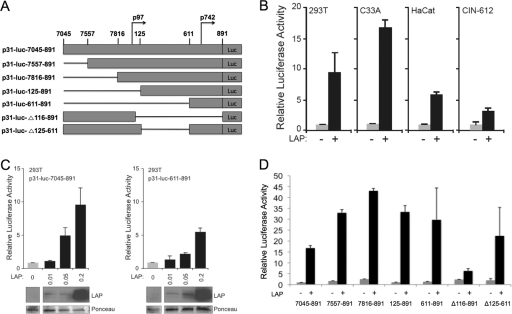

To study the roles of the LAP and LIP isoforms in regulating HPV-31 late gene expression, we first examined the effects of expression vectors in transient reporter assays. We initially wanted to determine whether LAP was capable of activating the HPV-31 late promoter and to identify reactive sequences. For this analysis, we made use of a luciferase reporter containing sequences from the 5′ end of the HPV-31 URR through the E6/E7 open reading frames (p31-luc-7045–891) (28, 32). Previous studies have shown that in this construct, the p97 early promoter contributes minimally to late gene expression upon keratinocyte differentiation (28). A series of epithelial cell lines, including C33A, HaCaT, 293T, and HPV-31-positive CIN-612 cells, were transfected with p31-luc-7045–891, in the presence or absence of an LAP expression plasmid, and assayed for luciferase activity 48 h posttransfection as described previously (28). In every cell line, coexpression of LAP resulted in a 5- to 16-fold increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 1B), and the increase in activity was dose responsive (Fig. 1C). These data indicated that LAP is capable of activating the HPV-31 late promoter in a variety of epithelial cells, and this is consistent with previous studies in HPV-16 (19).

Fig 1.

The C/EBPβ isoform LAP activates HPV-31 late gene expression upon keratinocyte differentiation. (A) Linear representation of the HPV-31 promoter-driven luciferase reporter constructs (p31-luc) used in this study. p31-luc-7045–891 contains sequences from nt 7045 to 7891 that include the 5′ end of HPV-31 URR through the E6/E7 open reading frames into E1. The deletion constructs depicted below p31-luc-7045–891 have been described previously (28). (B) Relative luciferase activity in extracts from 293T, C33A, HaCat, and CIN-612 cells transfected with p31-luc-7045–891 construct in the presence or absence of an LAP expression plasmid. (C) LAP activates HPV-31 late gene expression in a dose-dependent manner. Relative luciferase activity levels in extracts from 293T cells transfected with p31-luc-7045 or p31-luc-611–891 and in the presence of an increasing amount of an LAP expression construct are shown. Western blotting of C/EBPβ expression in the cells is shown below the graph. The membrane was subsequently stained with Ponceau S and used as a loading control. (D) Relative luciferase activity in extracts from C33A cells transfected with the indicated p31-luc deletion constructs in the presence or absence of an LAP expression plasmid. For the luciferase assays, the firefly luciferase activity was normalized to that of linked Renilla luciferase and the normalized luciferase activity level in the absence of LAP was set to 1; for panel D, p31-luc-7045–891 in the absence of LAP was set to 1. Each histogram bar represents the mean and standard error of the mean of the results of three independent experiments.

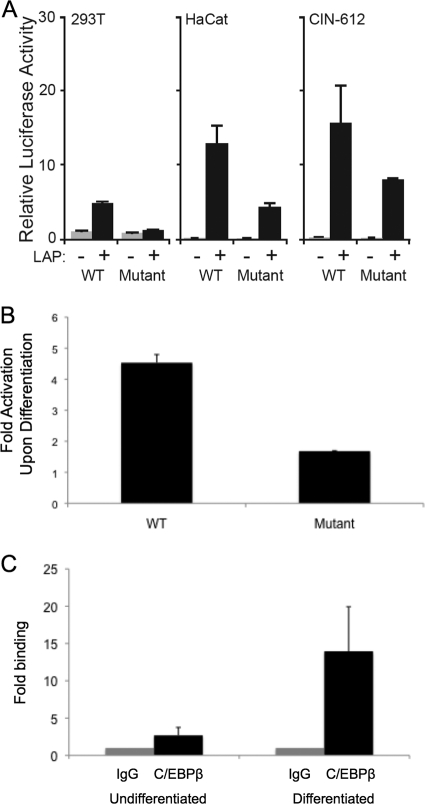

It was next important to map the LAP-responsive element within the HPV-31 late promoter. In order to localize the general responsive region, C33A were transfected with a series of p31-luc deletion constructs (Fig. 1A and reference 28), in the presence or absence of LAP, and assayed for luciferase activity 48 h posttransfection. Our studies indicated that the region spanning nt 611 to 891 was sufficient for LAP-mediated transcriptional enhancement of the HPV-31 late promoter (Fig. 1), while deletion of nt 125 to 611 had a minimal effect on activation. We were surprised that the region upstream of nt 611 was dispensable for LAP-mediated activation of the HPV-31 late promoter, since Kukimoto et al. reported that two C/EBPβ binding sites located at nt 583 and 604 in the HPV-16 promoter were required for C/EBPβ-mediated activation of the HPV-16 late reporters in transient assays (19). These two consensus C/EBPβ binding sites are also present in HPV-31 at nt 581 and 602 along with another putative C/EBPβ binding site located at nt 794 (TTGCAA). Since the 611–891 element retained responsiveness to C/EBPβ, we suspected that the activity was localized to nt 794 in HPV-31. To further investigate this hypothesis, we mutated the putative binding site at nt 794 to TAGGAC in p31-luc-611–891 and tested the responsiveness of the mutant reporter to LAP in HaCaT, 293T, and CIN-612 cells. We found significantly decreased luciferase activity with this mutant reporter compared to the wild-type luciferase reporter (Fig. 2A). The residual reporter activity was likely due to the action of other transcription factors important for late expression. These data indicated that the C/EBPβ binding site located at nt 794 is important for LAP-mediated transcriptional enhancement of the HPV-31 late promoter.

Fig 2.

Localization of the C/EBPβ-responsive sequences in HPV late promoter sequences with respect to nt 794. (A) Relative luciferase activity in extracts from 293T, HaCat, and CIN-612 cells transfected with wild-type p31-luc-611–891 or p31-luc-611–891 containing a mutated C/EBP binding site along with LAP expression vectors. Renilla luciferase was used as an internal control, and the mean normalized luciferase activity level in the absence of LAP was set to 1. (B) Late promoter reporter activity increases upon differentiation and is reduced when the C/EBPβ binding site at nt 794 is mutated. The histogram shows fold increases in luciferase activity upon keratinocyte differentiation of CIN-612 cells that were transfected with wild-type p31-luc-611–891 or p31-luc-611–891 containing a mutated C/EBP binding site at nt 794. At 24 h after transfection, half of the cells were induced to differentiate in methylcellulose for 24 h and the other half remained in a monolayer culture as previously described (28). Renilla luciferase was used as an internal control. Fold activation values represent the ratios of the normalized luciferase activity in extracts from differentiated CIN-612 cells to that of undifferentiated cells. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay representing the binding of C/EBP to the viral late gene promoter (nt 611 to 891) in both undifferentiated and differentiated states of CIN-612 cells. The IgG control ChIP fold level was set at 1 to facilitate comparisons. The binding of C/EBP to the viral late promoter was enriched about 5-fold upon differentiation and may have been due, in part, to increased template numbers due to amplification. The ChIP assay protocol was performed as described by Wong et al. (31), and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was done using a Lightcycler 480 Sybr green I Master kit (Roche Applied Science). The data are consistent with those of a previous study in which C/EBPβ was normalized to the amount of input DNA (32). Each histogram bar represents the mean and standard error of the mean of the results of three independent experiments.

Transient reporter assays using cotransfected expression vectors demonstrated a potential activating function only for C/EBPβ, and additional analyses are required to demonstrate that this element is actually important for the activation of HPV-31 late promoter activity upon keratinocyte differentiation. We therefore transfected HPV-31-positive CIN-612 cells with the wild-type or C/EBPβ binding site mutant luciferase reporter. At 24 h posttransfection, each plate was divided into a monolayer culture and a second culture that was suspended in medium containing 1.5% methylcellulose as previously described (13). After an additional 24 h, the cell lysates were harvested and assayed for luciferase activity. Our studies showed that mutation of the C/EBPβ binding site significantly inhibited late gene expression upon differentiation (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that the C/EBPβ binding site at nt 794 is required for efficient transcriptional enhancement of the late promoter upon keratinocyte differentiation, providing support for the hypothesis that C/EBPβ plays a central role in the activation of the HPV-31 late promoter.

It was next important to determine if C/EBPβ binds to the late promoter region of the HPV genome in vivo. For this analysis, quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed in HPV-31-positive CIN-612 cells induced to differentiate in methylcellulose. These analyses demonstrated that in undifferentiated cells, C/EBPβ binds to the viral genome in a region around nt 794 and that, following differentiation, binding increases significantly (Fig. 2C). The antibody used in these experiments binds all C/EBPβ isoforms. Upon differentiation, HPV-31 genomes are amplified, and it is likely that a portion of the enhanced binding of C/EBPβ seen upon differentiation was due to increased template numbers (13, 27). Since total HPV genome levels typically increase 3- to 5-fold upon amplification, a significant portion of the signal is due to enhanced binding of LAP isoforms. We also wanted to investigate if the binding site at nt 794 was important for late activation upon differentiation in the context of complete HPV genomes. For this analysis, site-directed mutagenesis was performed on HPV-31 clones to generate genomes in which the C/EBPβ binding suite at nt 794 was mutated so that it would be silent in the overlapping E7 ORF. We transfected the recircularized mutant HPV genomes into primary human keratinocytes as previously described (14), and in three independent experiments, we were not able to isolate stable clones. The failure of these mutant genomes to be stably maintained in undifferentiated cells is consistent with an important role for this C/EBPβ site in regulating viral transcription or replication.

The studies described above implicated the cellular transcription factor C/EBPβ in the regulation of HPV-31 late gene expression; however, the molecular mechanism by which C/EBPβ regulates this process in a differentiation-specific manner was still unclear, since previous studies indicated that C/EBPβ levels do not change upon differentiation (32). It has, however, been reported that the relative levels of the two C/EBPβ isoforms LIP and LAP change upon differentiation and so influence a number of cellular processes such as mammary gland development, hepatocyte differentiation, and adipogenesis (3, 7, 33). We therefore investigated if HPV-31 late gene expression might be regulated by changes in the relative levels of LIP and LAP.

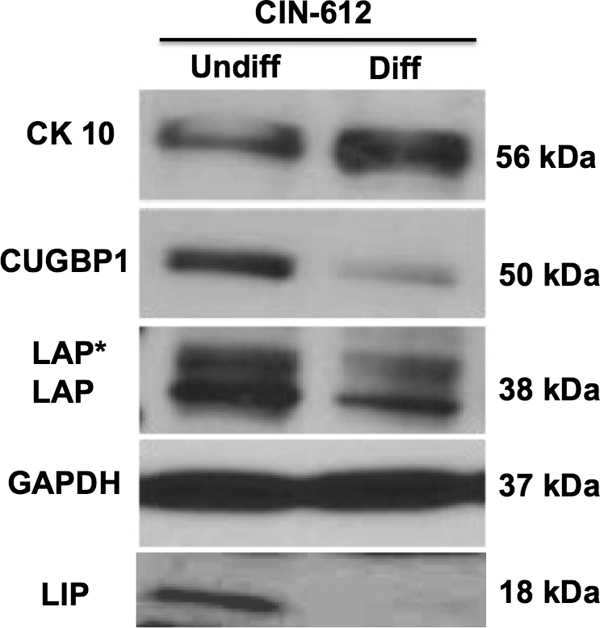

To determine if the ratio of LAP to LIP played any role in the regulation of the HPV late promoter, we first examined if LIP and LAP levels varied with differentiation of HPV-positive keratinocytes. For this analysis, CIN-612 cells were induced to differentiate by suspension in methylcellulose followed by Western blot analysis for LAP and LIP isoforms. Both the LAP and the LIP isoforms were detected in undifferentiated cells, and, following differentiation, LIP levels were significantly reduced (in some experiments to background levels), whereas LAP was maintained at similar or only slightly reduced levels (Fig. 3). This confirmed our initial hypothesis that keratinocyte differentiation alters the relative levels of LIP and LAP. We also wanted to see if the presence of viral proteins altered the relative levels of these isoforms during differentiation. To investigate this point, we performed Western blot analysis of stably transfected HPV-31 primary keratinocytes along with matched normal primary keratinocytes and observed that, upon differentiation, LIP was reduced to slightly lower levels in HPV-31-positive keratinocytes compared to normal keratinocytes while LAP levels were similar between the two types of cells (not shown). Overall, our observations are consistent with the idea that the relative abundance of LAP and LIP isoforms during differentiation was a crucial factor in activation of the late promoter. LIP is translated from the same messages as LAP, and synthesis is regulated by an RNA binding protein, CUGBP1, which binds the LIP AUG (29). We therefore investigated if decreased levels of LIP in differentiated HPV-positive cells correlated with decreased levels of CUGBP1. As seen in Fig. 3, the levels of CUGBP1 declined upon differentiation of HPV-positive cells and paralleled the reductions in LIP levels.

Fig 3.

LIP repressor levels are significantly reduced upon differentiation, while LAP/LAP* activator levels are only moderately reduced. C/EBP expression patterns in undifferentiated (Undiff) and differentiated (Diff) CIN-612 cells are shown. CIN-612 cells were cultured either as a monolayer or in methylcellulose for 48 h. The cells were lysed and analyzed by Western blotting as described previously (23) using a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific to C/EBP (Santa Cruz; sc-746). Upon differentiation, the protein level of the inhibitor isoform LIP was reduced nearly to background levels. The activator isoforms LAP* and LAP (38 kDa) were also reduced in level upon differentiation but were retained at significantly higher levels than LIP. The levels of the RNA binding protein CUGBP1, which has been shown to be important for LIP translation, were also reduced upon differentiation. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) levels are shown as loading controls.

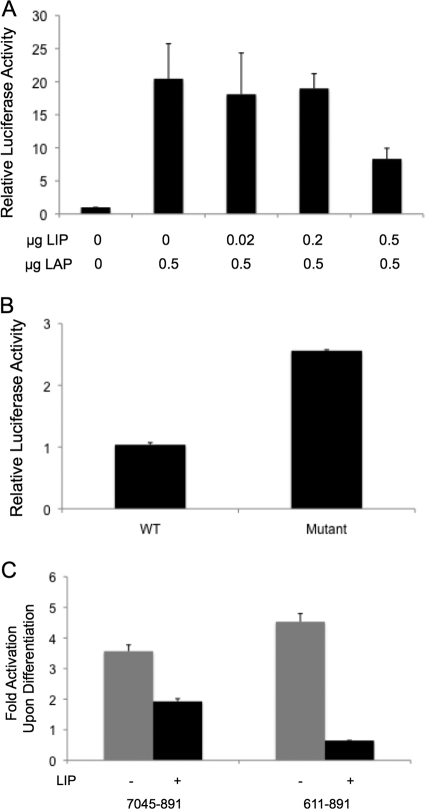

The LIP isoform lacks the transactivating domain found in the N terminus of LAP and, as a result, acts as a dominant-negative repressor of LAP-mediated activation. Our studies demonstrated that differentiation results in a significant drop in LIP levels (Fig. 3), and we next examined if changes in LIP levels could impede LAP-mediated activation of the HPV-31 late promoter. We first used transient assays to examine the effect of increasing LIP/LAP ratios on late promoter activation. For this analysis, cells were cotransfected with p31-luc-611–891 reporters together with a constant amount of LAP and increasing amounts of LIP. At 48 h posttransfection, the cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity and we observed inhibition of LAP-mediated late promoter activation with increasing amounts of LIP (Fig. 4A). This suggests that LIP is capable of inhibiting LAP's ability to activate the HPV-31 late promoter.

Fig 4.

The C/EBPβ LIP repressor inhibits C/EBPβ-mediated transcriptional activation of the HPV-31 late promoter. (A) Relative luciferase activity in lysate from 293T cells transfected with p31-luc-611–891 along with a constant amount of an LAP expression plasmid and an increasing amount of an LIP expression plasmid. Renilla luciferase was used as an internal control, and the mean normalized luciferase activity level in the absence of LAP and LIP was set to 1. (B) Relative luciferase activity in lysate from CIN-612 cells transfected with wild-type p31-luc-611–891 or p31-luc-611–891 containing a mutated C/EBP binding site. Renilla luciferase was used as an internal control, and the mean normalized luciferase activity level of wild-type p31-luc-611–891 was set to 1. (C) Fold increase in luciferase activity upon keratinocyte differentiation in the presence and absence of LIP. CIN-612 cells were transfected with p31-luc-7045–891 or p31-luc-611–891, in the presence or absence of an LIP expression plasmid. At 24 h after transfection, half of the cells were induced to differentiate in methylcellulose for 24 h. Renilla luciferase was used as an internal control. Fold activation values represent the ratios of the normalized luciferase activity in extracts from differentiated CIN-612 cells to that of undifferentiated cells. Each histogram bar represents the mean and standard error of the mean of the results of three independent experiments.

The results described above suggested that silencing of the HPV-31 late promoter in undifferentiated cells could be due to the high LIP level found in those cells (Fig. 3). If that is the case, then mutating the C/EBPβ binding site at nt 794 might alleviate this repression. We therefore transfected CIN-612 cells with the wild-type or C/EBPβ binding site mutant luciferase reporter and monitored luciferase activity 48 h posttransfection. As expected, the luciferase reporter with the mutated C/EBPβ binding site showed an increase in luciferase activity compared to the wild-type reporter (Fig. 4B). This suggested that LIP could contribute to the suppression of late gene expression in undifferentiated cells.

We next asked whether high-level expression of LIP could suppress late promoter activation upon keratinocyte differentiation. We therefore transfected CIN-612 cells with p31-luc-7045–891 or p31-luc-611–891 in the presence and absence of LIP. At 24 h posttransfection, we induced the cells to differentiate by incubating them in culture medium containing 1.5% methylcellulose and assayed luciferase activity 24 h later. In the presence of LIP, we observed consistent reductions in late promoter activation upon differentiation (Fig. 4C). This indicated that forced expression of LIP is sufficient to inhibit transcriptional activation of the HPV-31 late promoter, even upon keratinocyte differentiation.

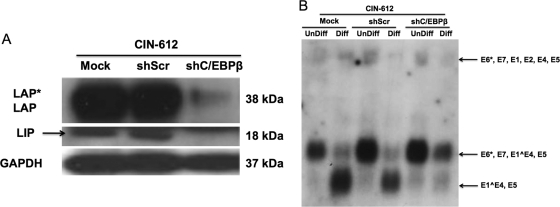

Finally, it was important to investigate what effect abrogating expression of C/EBPβ had on viral late gene expression from HPV-31 genomes. We screened five lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors for the ability to abrogate synthesis of C/EBPβ isoforms in short-term assays and determined that all the shRNA constructs were effective. Next, we infected CIN-612 cells with pooled concentrated supernatants of all the shRNA lentiviruses as previously described (21) and performed Western blot analysis for C/EBPβ isoforms in undifferentiated cells. Our studies demonstrated that the knockdown was specific for all the isoforms of C/EBPβ compared to mock and sh Scrambled (Scr) controls (Fig. 5A). The transduced CIN-612 cells were then suspended in 1.5% methylcellulose to induce differentiation, and late gene expression was analyzed by Northern analysis. As shown in Fig. 5B, late gene transcripts were significantly reduced in C/EBPβ knockdown cells compared to mock and Scrambled-transduced controls. Similar results were observed in multiple independent experiments. In addition, we observed that early transcripts initiating at the p97 early promoter were increased in C/EBPβ knockdown cells, suggesting that early gene transcription is repressed by C/EBPβ upon differentiation.

Fig 5.

Lentivirus-mediated shRNA knockdown of C/EBPβ resulted in reduced viral late gene expression upon differentiation of cells stably maintaining HPV-31 episomes. Lentivirus virions were produced from five different validated shRNAs targeting C/EBP (3 μg each) by transfection along with pTatRevGagPol (2 μg) and pVSVG (1 μg) into HEK 293T cells. At 48 h posttransfection, the virions were collected and were individually concentrated by the use of centrifugation filters (Millipore) per the manufacturer's instructions. The concentrated virions from all the shRNAs were pooled at equal volumes and were used to infect CIN-612 cells. (A) Western blot representing the knockdown of C/EBPβ (LAP*, LAP, and LIP) in CIN-612 cells by sh C/EBPβ compared to sh Scr (scrambled control) and mock-infected cells. GAPDH served as a loading control. (B) Northern blot analysis was performed for HPV transcripts as previously described by the use of CIN 612 cells in which C/EBPβ levels were reduced. In cells in which C/EBPβ levels had been reduced, the levels of the major late transcripts encoding E1̂E4,E5 were significantly reduced upon differentiation compared to shScr and mock-infected cells. Levels of early E6*,E7,E1̂E4,E5 transcripts were found to be increased in cells in which C/EBPβ levels had been reduced.

Our studies indicate that activator and repressor isoforms of the C/EBPβ family are major regulators of the HPV-31 late promoter. Abrogation of C/EBPβ isoforms through use of shRNAs resulted in significantly reduced levels of late transcripts expressed from episomal genomes that are stably maintained in human keratinocytes. We observed that the activator forms of C/EBPβ LAP and LAP* were maintained at comparable levels upon differentiation of HPV-positive cells, whereas the levels of the LIP repressor forms were significantly decreased. Since the LIP isoforms act as dominant-negative repressors of LAP function, we conclude that the differentiation-dependent reductions in LIP levels play a major role in activation of the HPV late promoter.

LIP is translated from the same messages as the LAP activator forms but initiates at the third AUG codon from the 5′ end, whereas LAPs initiate at the first AUG codon. Initiation of LIP translation is regulated by a leaky scanning mechanism that is regulated by the CUGBP1 protein (29, 33). In our studies, we observed a decrease in CUGBP1 levels upon differentiation that correlated with reduced levels of LIP and implicates it as an upstream regulator of the late promoter activation. We suggest the following model. In undifferentiated cells, LIP-LAP dimers predominate and bind to the HPV-31 late promoter sequences, resulting in the repression of late gene expression. Upon differentiation, CUGBP1 protein levels decline, resulting in decreased LIP levels and increased formation of LAP homodimers. LAP homodimers predominate at the late promoter in differentiated cells, contributing to the activation of HPV-31 late gene expression. A number of potential C/EBPβ putative binding sites are present both in the URR and in the late promoter region, and our studies indicated that the C/EBPβ binding site at nt 794 in HPV-31 is the most important for regulating late gene expression.

We previously used a mutational analysis of sequences in the E7 ORF of complete HPV genomes to identify another element important for HPV pathogenesis, CAGCTCAG, at nt 665 that is also important for activation of late gene expression upon differentiation (4). The factor that binds this sequence is unknown, and its binding sequence does not correspond to that of any previously characterized factor but likely acts cooperatively with C/EBPβ to activate late expression. We base this conclusion on our C/EBPβ knockdown studies in which reduced levels of C/EBPβ alone were sufficient to block HPV late transcription and on the fact that mutation of the CAGCTCAG element also abrogated late activity. In addition to sequences in the E7 ORF that control differentiation-dependent activation of the late promoter, we previously observed using reporter assays that sequences in the URR could enhance the levels of activation (32). We believe that sequences in the E7 ORF control the differentiation-dependent activity whereas elements in the URR may contribute to the level of activation. In the present study, we also observed that levels of early transcripts from episomal genomes were increased in differentiated cells when C/EBPβ is knocked down. This is consistent with reports in transient assays that C/EBPβ could negatively regulate early transcription (19, 20). Interestingly, the negative regulation of early transcription occurred only in differentiated cells, suggesting that additional factors besides LIP are involved in the regulation of the early promoter in differentiated cells. Overall, our studies have shown the differentiation-dependent activation of HPV late promoter activity to be dependent upon the C/EBPβ transactivators and that loss of the repressor form plays a central role in this regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Laimins laboratory for helpful discussions. LAP and LIP expression plasmids were a kind gift from Janice Clements.

This work was supported by a grant to L.L. from the NCI.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 February 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Apt D, Watts RM, Suske G, Bernard HU. 1996. High Sp1/Sp3 ratios in epithelial cells during epithelial differentiation and cellular transformation correlate with the activation of the HPV-16 promoter. Virology 224:281–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baer M, Johnson PF. 2000. Generation of truncated C/EBPbeta isoforms by in vitro proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:26582–26590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baldwin BR, Timchenko NA, Zahnow CA. 2004. Epidermal growth factor receptor stimulation activates the RNA binding protein CUG-BP1 and increases expression of C/EBPbeta-LIP in mammary epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:3682–3691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bodily JM, Mehta KP, Cruz L, Meyers C, Laimins LA. 2011. The E7 open reading frame acts in cis and in trans to mediate differentiation-dependent activities in the human papillomavirus type 16 life cycle. J. Virol. 85:8852–8862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bodily JM, Meyers C. 2005. Genetic analysis of the human papillomavirus type 31 differentiation-dependent late promoter. J. Virol. 79:3309–3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Butz K, Hoppe-Seyler F. 1993. Transcriptional control of human papillomavirus (HPV) oncogene expression: composition of the HPV type 18 upstream regulatory region. J. Virol. 67:6476–6486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calkhoven CF, Muller C, Leutz A. 2000. Translational control of C/EBPalpha and C/EBPbeta isoform expression. Genes Dev. 14:1920–1932 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chong T, Chan WK, Bernard HU. 1990. Transcriptional activation of human papillomavirus 16 by nuclear factor I, AP1, steroid receptors and a possibly novel transcription factor, PVF: a model for the composition of genital papillomavirus enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:465–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cripe TP, et al. 1990. Transcriptional activation of the human papillomavirus-16 P97 promoter by an 88-nucleotide enhancer containing distinct cell-dependent and AP-1-responsive modules. New Biol. 2:450–463 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. del Mar Peña LM, Laimins LA. 2001. Differentiation-dependent chromatin rearrangement coincides with activation of human papillomavirus type 31 late gene expression. J. Virol. 75:10005–10013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Demeret C, Desaintes C, Yaniv M, Thierry F. 1997. Different mechanisms contribute to the E2-mediated transcriptional repression of human papillomavirus type 18 viral oncogenes. J. Virol. 71:9343–9349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Descombes P, Schibler U. 1991. A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell 67:569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fehrmann F, Klumpp DJ, Laimins LA. 2003. Human papillomavirus type 31 E5 protein supports cell cycle progression and activates late viral functions upon epithelial differentiation. J. Virol. 77:2819–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frattini MG, Lim HB, Laimins LA. 1996. In vitro synthesis of oncogenic human papillomaviruses requires episomal genomes for differentiation-dependent late expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:3062–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grassmann K, Rapp B, Maschek H, Petry KU, Iftner T. 1996. Identification of a differentiation-inducible promoter in the E7 open reading frame of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) in raft cultures of a new cell line containing high copy numbers of episomal HPV-16 DNA. J. Virol. 70:2339–2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hubert WG, Kanaya T, Laimins LA. 1999. DNA replication of human papillomavirus type 31 is modulated by elements of the upstream regulatory region that lie 5′ of the minimal origin. J. Virol. 73:1835–1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hummel M, Hudson JB, Laimins LA. 1992. Differentiation-induced and constitutive transcription of human papillomavirus type 31b in cell lines containing viral episomes. J. Virol. 66:6070–6080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kanaya T, Kyo S, Laimins LA. 1997. The 5′ region of the human papillomavirus type 31 upstream regulatory region acts as an enhancer which augments viral early expression through the action of YY1. Virology 237:159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kukimoto I, Takeuchi T, Kanda T. 2006. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta binds to and activates the P670 promoter of human papillomavirus type 16. Virology 346:98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kyo S, et al. 1993. NF-IL6 represses early gene expression of human papillomavirus type 16 through binding to the noncoding region. J. Virol. 67:1058–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mighty KK, Laimins LA. 2011. p63 is necessary for the activation of human papillomavirus late viral functions upon epithelial differentiation. J. Virol. 85:8863–8869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moody CA, Laimins LA. 2010. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10:550–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moody CA, Laimins LA. 2009. Human papillomaviruses activate the ATM DNA damage pathway for viral genome amplification upon differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Münger K, Howley PM. 2002. Human papillomavirus immortalization and transformation functions. Virus Res. 89:213–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ozbun MA, Meyers C. 1997. Characterization of late gene transcripts expressed during vegetative replication of human papillomavirus type 31b. J. Virol. 71:5161–5172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ramji DP, Foka P. 2002. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem. J. 365(Pt. 3):561–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruesch MN, Laimins LA. 1998. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins alter differentiation-dependent cell cycle exit on suspension in semisolid medium. Virology 250:19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spink KM, Laimins LA. 2005. Induction of the human papillomavirus type 31 late promoter requires differentiation but not DNA amplification. J. Virol. 79:4918–4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Timchenko NA, Welm AL, Lu X, Timchenko LT. 1999. CUG repeat binding protein (CUGBP1) interacts with the 5′ region of C/EBPbeta mRNA and regulates translation of C/EBPbeta isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:4517–4525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang HK, Duffy AA, Broker TR, Chow LT. 2009. Robust production and passaging of infectious HPV in squamous epithelium of primary human keratinocytes. Genes Dev. 23:181–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong PP, Pickard A, McCance DJ. 2010. p300 alters keratinocyte cell growth and differentiation through regulation of p21(Waf1/CIP1). PLoS One 5:e8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wooldridge TR, Laimins LA. 2008. Regulation of human papillomavirus type 31 gene expression during the differentiation-dependent life cycle through histone modifications and transcription factor binding. Virology 374:371–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zahnow CA, Cardiff RD, Laucirica R, Medina D, Rosen JM. 2001. A role for CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta-liver-enriched inhibitory protein in mammary epithelial cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 61:261–269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]