Abstract

Rotaviruses (RVs), an important cause of severe diarrhea in children, have been found to recognize sialic acid as receptors for host cell attachment. While a few animal RVs (of P[1], P[2], P[3], and P[7]) are sialidase sensitive, human RVs and the majority of animal RVs are sialidase insensitive. In this study, we demonstrated that the surface spike protein VP8* of the major P genotypes of human RVs interacts with the secretor histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs). Strains of the P[4] and P[8] genotypes shared reactivity with the common antigens of Lewis b (Leb) and H type 1, while strains of the P[6] genotype bound the H type 1 antigen only. The bindings between recombinant VP8* and human saliva, milk, or synthetic HBGA oligosaccharides were demonstrated, which was confirmed by blockade of the bindings by monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) specific to Leb and/or H type 1. In addition, specific binding activities were observed when triple-layered particles of a P[8] (Wa) RV were tested. Our results suggest that the spike protein VP8* of RVs is involved in the recognition of human HBGAs that may function as ligands or receptors for RV attachment to host cells.

INTRODUCTION

Rotaviruses (RVs) are the most important cause of severe gastroenteritis in children. As a member of the reovirus family, RV has an icosahedral structure that consists of three concentric protein layers surrounding the double-stranded-RNA genome. To initiate an infection, the virion must pass through the host cell membrane by attachment to a cellular receptor, followed by delivery of its double-layered subviral particle into the cytoplasm (2, 16, 18, 23, 28, 42, 52, 53). Two major structural proteins, VP4 and VP7, are found on the outmost surfaces of the virions (11, 37). VP7 is a glycoprotein found rich in the endoplasmic reticulum of the infected cells and is mainly involved in virion assembly, while VP4 forms the major spike protein responsible for viral attachment and penetration into host cells (17, 28, 46, 47).

VP4 is processed by proteolytic cleavage into two subunits, VP5* and VP8* (14, 44, 45). VP8* is believed to be mainly involved in the attachment of viruses to host cells and VP5* in the translocation of the double-shelled particles into the cytoplasm through conformation rearrangement and membrane fusion (2, 14, 43), although the precise functions of the two subunits remain to be defined. Some RV strains recognize the terminal N-acetyl neuraminic (sialic) acid (SA) residues of carbohydrates on the host cell surface for attachment (15, 63, 64). However, this interaction appears nonessential for other strains (9, 41). RV-SA recognition has relied mainly on observation of neuraminidase sensitivity tests previously (36, 65), in which a strain was considered sialidase sensitive if its infection is sensitive to neuraminidase treatment. Recent reports showed that neuraminidase is capable of removing the terminal SAs without affecting subterminal SAs, and the infectivity and cell binding of two “sialidase-insensitive” RVs (Wa and DS-1) were increased following treatment of the host cells with neuraminidase (20, 27). Thus, the relative roles of the terminal versus the subterminal SAs in infection of RVs, particularly of the “sialidase-insensitive” human and animal RVs, remain unknown.

The sensitivity of RVs to sialidase treatment is associated with the VP8* sequence of P genotypes but not with their host origin, suggesting a linkage between the protein VP8* and viral attachment to host cells (9). RVs of P[1], P[2], P[3], and P[7] genotypes can be found in both humans and animals, and these RVs are mainly sialidase sensitive (9). Three P types (P[4], P[6], and P[8]) have been found to commonly cause gastroenteritis in humans, but none of them are sialidase sensitive (8). Thus, we hypothesize that these P types of human RVs may recognize an alternative carbohydrate, such as the human histo-blood group antigen (HBGAs), similarly to human noroviruses (NoVs) (57).

HBGAs are complex carbohydrates present on the surfaces of red blood cells and mucosal epithelia of the respiratory, genitourinary, and digestive tracts (10, 19, 21, 22, 33). They are also present as free oligosaccharides in biologic fluids, such as saliva, intestinal contents, milk, and blood (38). The biosynthesis pathway of HBGA starts with a disaccharide precursor by sequential additions of monosaccharides catalyzed by glycosyltransferases encoded by three major gene families, the ABO, Lewis, and secretor families. Each of the gene families contains silent alleles, leading to null phenotypes of the loci. For example, the FUT2-inactivated mutations are responsible for the nonsecretor phenotype found in about 20% of European and North American populations. The nonsecretor phenotype is characterized by the absence of ABH antigens in saliva and on most epithelial cells of the respiratory, genitourinary, and digestive tracts.

Human NoVs recognize different host HBGAs of individuals with different genetic makeups of the ABO, secretor, and Lewis families. The major human blood types of secretor, A/B, and Lewis bloods are determined by three unique terminal saccharides. They are α-1,2-fucose, α-N-acetylgalactosamine/α-galactose, and α-1,3/4-fucose, respectively. These three saccharides have been shown to play an important role in binding to NoVs (57). SA is another residue that commonly occurs on mucosal surfaces, and this residue has been suggested to be involved in binding to some NoVs (48, 60). We hypothesize that RVs could share common carbohydrates as receptors with NoVs because RVs and NoVs may infect the same enterocytes in the intestinal tract.

Interaction of human RV with a carbohydrate has also been suggested by a crystallographic study of RV VP8* proteins of a sialidase-sensitive animal strain (CRW-8) and a sialidase-insensitive human strain (Wa) (7). A comparison of these two atomic structures showed that the SA binding pocket is missing for the sialidase-insensitive strain Wa. Instead, the crystal structure of WA VP8* revealed a novel groove region that is suggested to interact with carbohydrate (7). In addition, this groove is found to be conserved in both the sialidase-insensitive human strains and the sialidase-sensitive animal strains (7). Similar findings were reported in a separate study comparing the RRV (sialidase-sensitive) and DS-1 (sialidase-insensitive) VP8* proteins, in which a similar surface cleft was found on the DS-1 VP8* protein (43).

In this study, we provided the first evidence of interaction between human RVs and HBGAs in human saliva and milk. The results were further validated by binding of VP8* to synthetic oligosaccharides representing specific HBGAs and by blocking the binding by monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) specific to these HBGAs. More importantly, we observed similar binding activities with the use of authentic RVs recovered from cell cultures. While direct evidence is still needed, our results suggest that the sialidase-insensitive human RVs may recognize human HBGAs as ligands or receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus strains and primers.

Different VP4 genotypes of human RVs, including cell culture-adapted RVs {Wa (P[8]) (GenBank accession no. M96825), RVP (P[8]) (GenBank accession no. EF672598), DS1 (P[4]) (GenBank accession no. EF672577), and ST3 (P[6]) (GenBank accession no. L33895)} and RV strains directly isolated from stool samples {BM13851 (P[8]), BM14113 (P[8]), BM151 (P[8]), BM5265 (P[4]), and BM11596 (P[6])}, were studied. A set of primers was designed (Table 1) to amplify the VP8*- and VP8* core (deletion of the first 64 amino acids)-encoding cDNA fragments by PCR. Viral RNAs were extracted either from cell culture or from clinic stool samples.

Table 1.

Primers used for amplification of the RV VP8* and VP8* core coding region

| Primera | Sequence | Restriction enzyme site | Strain (position) | P genotype(s) to be amplified | Sense |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P541 | 5′-CGTGGATCCATGGCTTCGCTCATTTATAGACA | BamHI | Wa (10–32) | P[8], P[6], P[4] | Positive |

| P556 | 5′-AGTGTCGACTCAGTCATCTAGTATTTTGAATTGGTGGTA | SalI | Wa (699–721) | P[8], P[6], P[4] | Negative |

| P1182 | 5′-CGTGGATCCGCTCCAGTCAATTGGGGTCATGGA | BamHI | Wa (145–168) | P[8] | Positive |

| P1183 | 5′-CGTGGATCCGCTCCAGTTGATTGGGGACACGGA | BamHI | RV5 (145–168) | P[4] | Positive |

| P1184 | 5′-CGTGGATCCGCACCAGTGACTTGGAGTCATGGGG | BamHI | ST3 (145–168) | P[6] | Positive |

| P1185 | 5′-AGTGTCGACTCAGTCATCTAGTATTTTGAATTGGTGG | SalI | Wa (679–699) | P[8], P[6], P[4] | Negative |

| P1186 | 5′-AGTGTCGACTCAGTCACCTTGTATTCTGCATTGGTGGTA | SalI | US1205 (677–699) | P[6] | Negative |

| P1279 | 5′-ACAACTAGTTTAGATGGTCCTTATCAAC | SpeI | Wa (202–220) | P[8], P[4] | Positive |

| P1281 | 5′-GATATCGATTAGACCGTTGTTAATATATTCATTACA | ClaI | Wa (656–678) | P[8], P[4] | Negative |

| P1509 | 5′-ACAACTAGTCTCGATGGTCCTTATCAAC | SpeI | BM11596 (202–220) | P[6] | Positive |

| P1510 | 5′-GATATCGATTAACCCAGTATTTATGTATTCACTACA | ClaI | BM11596 (656–678) | P[6] | Negative |

| P1504 | 5′-CGTGTCGACATGGCTTCGCTCATTTATAGACA | SalI | Wa (10–32) | P[8], P[6], P[4] | Positive |

| P1505 | 5′-GTGCGGCCGCTCAGTCATCTAGTATTTTGAATTGGTGGTA | NotI | Wa (699–721) | P[8], P[6], P[4] | Negative |

For expression of VP8*-GST fusion proteins, primer pair P541-P556 was used for amplification of VP8*, and primer pairs P1182-P1185, P1183-P1185, and P1184-P1186 were used for amplification of VP8* core. For expression of VP8* presented by the NoV P particle, primer pairs P1279-P1281 and P1509-P1510 were used for amplification of VP8* core. For expression of the VP8*-NoV S domain fusion protein, primer pair P1504-P1505 was used for amplification of VP8*.

Cloning, expression, and purification of VP8*.

The cDNAs encoding RV VP8* or VP8* core were cloned into the expression vector pGEX-4T-1 (glutathione S-transferase [GST]–gene fusion system; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) at the SalI and BamHI sites; after sequence confirmation, full-length VP8* and VP8* core fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 as described previously (55, 58, 59). For presentation of RV VP8* on the P particle of a genogroup II, genotype 4 (GII.4) norovirus (VA387), the P particle vector with a cloning cassette constructed previously (56) was used for cloning RV VP8* core into loop 2 of the P particle. For presentation of RV VP8* by the S protein, RV VP8* was fused to the C terminus of the shell (S) domain of VA387, which was cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 GST expression vector. Briefly, the expressions were induced by IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; 0.4 mM) at room temperature (∼22°C) overnight. RV VP8*-GST fusion protein was purified using glutathione Sepharose 4 fast flow (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The free VP8*, VP8*-P domain, and VP8*-VA387 S domain fusion proteins were released from GST by thrombin (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) digestion at room temperature overnight. The possible high-molecular-weight (MW) complex formation was examined by using size exclusion gel filtration (Superdex 200; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Testing of RV VP8* attachment to carbohydrates in human saliva by EIA.

The saliva samples used in these studies were selected from a set of well-defined saliva samples previously described (24, 25). Saliva binding enzyme immune assays (EIA) were used to detect binding of recombinant VP8*/VP8* core to carbohydrates in saliva as described previously (24, 25). Boiled saliva samples were diluted at 1:1,000 and coated onto 96-well microtiter plates (Dynex Immulon; Dynatech, Franklin, MA) at 4°C overnight. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, free VP8* or VP8* fusion proteins at 5 to 15 μg/ml or as indicated were added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The bound VP8* proteins were detected using guinea pig serum anti-BM151 VP8* at 1:5,000, followed by addition of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (ICN, Aurora, OH). The signal intensities were displayed by a TMB kit (Kierkegaard and Perry Laboratory, Gaithersburg, MD), and then the optical density (OD) at 450 nm was read using an EIA spectra reader (Tecan, Durham, NC). In each step, the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–Tween 20 using a plate washer.

Testing of RV VP8* attachment to synthetic oligosaccharides.

For the oligosaccharide-based binding assays, microtiter plates were coated with recombinant VP8* at 5 to 15 μg/ml at 4°C overnight or 37°C for 1 h as indicated. After blocking with 5% Blotto nonfat milk, oligosaccharide-polyacrylamide (PAA)-biotin conjugates (2 μg/ml) or oligosaccharide-6-aminohexanoate (LC)–biotin (2 μg/ml) was incubated at 4°C overnight. Bound oligosaccharides were detected using HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) and displayed using the TMB kit as described above. A panel of oligosaccharide-PAA/LC-LC-biotin conjugates (Table 2) from two resources (GlycoTech Corporation, Rockville, MD, and Consortium for Functional Glycomics [CFG]) was used for screening possible interaction.

Table 2.

Panel of synthetic oligosaccharides used in detection of RV VP8*-oligosaccharide interactions

| Oligosaccharide conjugate | Sourcea |

|---|---|

| Lea-LC-LC | CFG |

| H type 1-LC-LC | CFG |

| H type 2-LC-LC | CFG |

| Ley-LC-LC | CFG |

| TriLex-LC-LC | CFG |

| H type 2-LC-LC | CFG |

| A tetra type 2-LC-LC | CFG |

| B tetra type 2-LC-LC | CFG |

| B tetra type 1-LC-LC | CFG |

| A tetra type 1-LC-LC | CFG |

| Lex-LC-LC | CFG |

| Lex-PAA (30 kDa) | CFG |

| Lex-PAA (1 MDa) | CFG |

| H type1-PAA (30 kDa) | CFG |

| H type1-PAA (1 MDa) | CFG |

| 3′SLea-PAA (1 MDa) | CFG |

| 3′SLex-PAA (1 MDa) | CFG |

| Tri-Lex-PAA (30 kDa) | CFG |

| Tri-Lex-PAA (1 MDa) | CFG |

| Lea-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| Leb-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| Lex-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| Ley-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| H type 1-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| H type 2-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| H type 3-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| Adi-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| Bdi-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| Atri-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| Btri-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| SLea-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

| SLex-PAA | GlycoTech, Inc. |

CFG, Consortium for Functional Glycomics (a large research initiative funded by NIGMS to define the paradigms by which protein-carbohydrate interactions mediate cell communication [https://www.functionalglycomics.org]).

Blocking of binding of RV VP8* to saliva and oligosaccharides by MAbs.

The same conditions and procedure of saliva binding assays as those described above were used with an additional blocking step, in which saliva-coated plates were preincubated with MAbs specific to Lea, Leb, Lex, Le y, H type 1, and H type 2 at a dilution of 1:20 for 1 h at 37°C, before addition of recombinant VP8* to the plate. The blocking levels (%) were calculated by comparing the OD450 values between wells with or without incubation with a MAb.

Preparation of RV DLPs and TLPs by CsCl gradient centrifugation.

A cell culture-adapted P[8] RV (Wa) was studied. A total of 1.0 liter of Wa-infected MA 104 cell cultures from 12 rolling bottles was harvested. After three cycles of freeze-thawing of the samples and clarification by a low-speed centrifugation, the viruses in the supernatants were concentrated by pelleting them at 28,000 rpm for 3 h using a SW28 rotor (Beckman). The viruses in the pellets were resuspended in TNC buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5) containing CsCl. The final density of the sample was adjusted to a refractive index of 1.369 before the sample was loaded into the rotor. After centrifugation at 288,000 × g for 46 h using a SW41Ti rotor (Beckman), the gradient was fractioned by bottom puncture and ∼0.5-ml fractions were collected. The fractions containing double-layered particles (DLPs) or triple-layered particles (TLPs) were identified based on the densities and then dialyzed against TNC buffer. The resulting DLP and TLP preps were examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using negative staining and further confirmed by Western blot analysis using a VP8*-specific MAb. The DLP and TLP preps were then quantified by SDS-PAGE based on the extensity of the major VP6 protein on the gels, and equal amounts of viruses were used to determine the cell culture infectivity.

Binding of CsCl gradient-purified DLPs and TLPs to saliva samples.

Procedures similar to those for the saliva binding assays described above were used. Briefly, boiled saliva samples were diluted at 1:1,000 and coated onto 96-well microtiter plates at 4°C overnight. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, fractions 7 and 10, which contain DLPs and TLPs, respectively, from the Wa CsCl gradient were added at 1:10 with 1% nonfat milk. After an overnight incubation at 4°C, the binding signals were detected by the HRP-antibody enzyme conjugate from the Rotaclone kit (Meridian Biosciences, Cincinnati, OH).

Research using clinical specimens.

Human saliva and milk samples used in this study were archived samples from previous studies (24, 25, 29) approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

RESULTS

The VP8* proteins of P[8] and P[4] RVs recognize the Leb and/or H type 1 antigens.

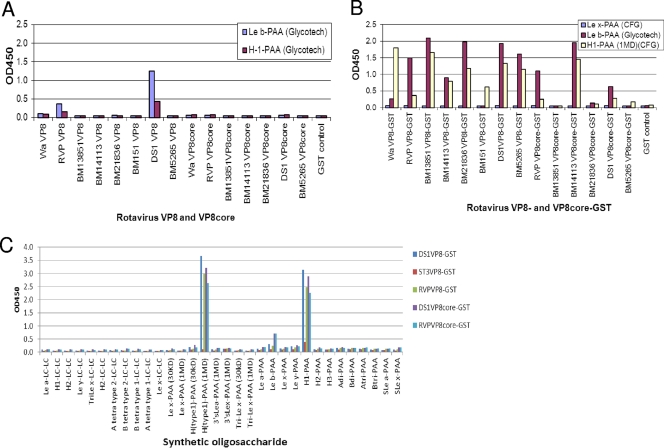

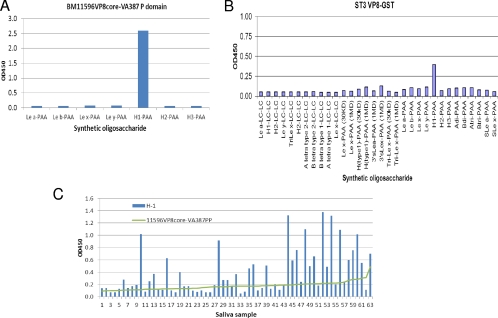

We initiated our study by performing saliva- and oligosaccharide-based binding assays using recombinant RV spike proteins made from E. coli cultures. When highly purified VP8* proteins from a number of P[4] and P[8] RVs were examined, the signals for binding to saliva were very weak and not stable (data not shown), but binding activities with synthetic oligosaccharides of Leb and H type 1 antigens were clearly observed for two strains of P[8] and P[4], respectively (Fig. 1A). Notably, the binding signals increased significantly when the GST-VP8* fusion proteins were tested (Fig. 1B and C). GST fusion of VP8* from 2 P[4] and 5 P[8] strains, including RVs isolated directly from stool specimens and cell culture-adapted strains (Wa, DS-1, and RVP), revealed similar binding profiles for Leb and H type 1 antigens (Fig. 1B). The binding activities were from VP8*, not from the GST tag, because purified GST proteins alone did not reveal any binding activity (Fig. 1B). We also performed binding assays on extended HBGA oligosaccharides with selected P[4] and P[8] strains; among a panel of 32 oligosaccharides from different sources tested, only the Leb and H type 1 antigens revealed strong binding activities (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

Binding of recombinant RV VP8* to synthetic oligosaccharides. Recombinant proteins with the full-length or the core region of the RV VP8* from seven P[8] or P[4] human RVs were tested for binding to oligosaccharides with (A) or without (B) removal of the GST tag. Except for BM13851 VP8* core-GST to H type 1-PAA and BM13851 VP8* core-GST, BM151 VP8*-GST, and BM5265 VP8* core-GST to Leb-PAA, all VP8*- and VP8* core-GST proteins showed significant binding to Leb and H type 1 antigens compared with binding to Lex-PAA (means + 2 standard deviations [SD]). (C) One of each of the P[4] (DS1) and P[8] (RVP) RVs was tested with extended oligosaccharides representing variable HBGAs from two different sources (GlycoTech Corp. and the CFG) to confirm the binding specificities to the Leb and H type 1 antigens.

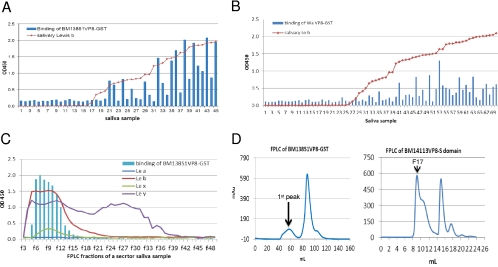

The oligosaccharide binding results for the GST-VP8* fusion proteins were confirmed by the saliva-based binding assays, in which a strong association of binding signals for 2 selected P[8] strains with the salivary Leb antigen were detected using a panel of well-characterized saliva samples (Fig. 2A and B). The relationship of binding of VP8* to H type 1 was difficult to establish due to the low signal intensity of H type 1 in most of the saliva samples tested, particularly in Leb-positive individuals, because H type 1 is the precursor of Leb. The products derived from the type 2 precursor may not be involved, because no correlation of Ley with VP8* binding was identified (Fig. 2C). In addition, we noticed an influence of binding by the type B epitope. Among the Leb-positive individuals, the signals for binding to the type B saliva were significantly lower than those for binding to the type A/AB and O saliva for both of the P[8] strains studied (Fig. 3), suggesting that the terminal α-galactose (the type B epitope) may interfere with the binding by masking the H epitope (α 1,2-fucose), the major determinant of the secretor type. No such interference by the type A epitope was observed.

Fig 2.

Binding of recombinant RV VP8* to saliva. (A and B) VP8*-GST fusion proteins from 2 P[8] (BM13851, Wa) human RVs were tested for binding to a panel of saliva samples. The results for binding of VP8* to individual saliva samples were plotted according to a sorting of the Leb signals of individual saliva samples. Saliva samples were boiled before being used in the assays to remove antibodies fractionation by may interfere with the binding results. A correlation between the salivary Leb and VP8* binding levels for both strains was observed. (C) Binding of an RV VP8* (BM13851) to a secretor saliva sample following the fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC). The signals of Lea, Leb, Lex, and Ley of individual fractions were determined by a MAb-based EIA. The VP8*-GST fusion protein bound only to the high-molecular-weight fractions containing the Leb antigen. The chart was made by sorting of binding signals that were presented in line with markers instead of bars indicating correlation with the salivary Lewis antigens. (D) Gel filtration profiles of RV VP8*-GST (Superdex 200 16/60 GL) and VP8*-VA387 S domain fusion proteins (Superdex 200 10/300 GL). The molecular masses of the 1st peak of BM13851 VP8*-GST and fraction 17 (F17) of the BM14113 VP8* S domain were >440 kDa and >800 kDa, respectively.

Fig 3.

Characterization of saliva binding signals of RV VP8* based on ABO typing of saliva. The signals for binding of VP8*-GST of BM13851 (A) and Wa (B) to saliva from type A/AB, B, and O secretors (Leb positive) were compared. The low-level binding of VP8* to type B secretor saliva may due to a steric interference from B antigen. The individuals in each of the three groups were sorted from low to high binding strength (OD).

The binding of VP8* was enhanced by fusion to the shell (S) or protruding (P) domains of NoV capsid protein.

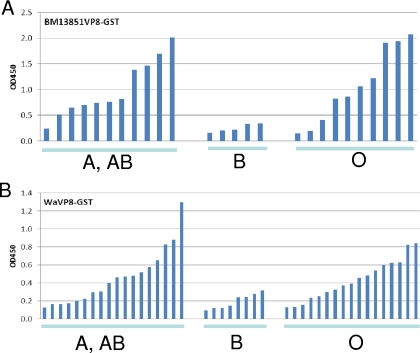

In our separate studies, we found that the norovirus (NoV) capsid protein can be used as an excellent scaffold for presentation of foreign antigens for immune enhancement (57). To further verify the HBGA binding activities of VP8* described above, recombinant chimeric NoV P particles with VP8* proteins inserted in one of the surface loops of the P protein were constructed. In addition, VP8* fusion proteins fused to the C terminus of the NoV S protein were developed. The VP8* antigens were well presented by both P and S proteins; 24 copies of VP8* were present on each P particle (57), and high-molecular-weight complexes of the S-VP8* fusion proteins were detected by gel filtration analysis (Fig. 2D). High binding activities with minor variations compared with the activities of the GST-presented VP8* protein were observed (Fig. 4). The S-VP8* fusion proteins revealed binding to both the Leb and the H type 1 oligosaccharides that was identical to that of the VP8*-GST fusion proteins, although the P particle-presented VP8* protein mainly bound to the Leb oligosaccharide (Fig. 4A and B). The saliva binding patterns were more consistent: both the P particle- and the S protein-presented VP8* proteins bound specifically to the Leb-positive secretors, with similar strain variations among a panel of saliva samples studied (Fig. 4C and D).

Fig 4.

Binding of RV VP8* presented by the NoV VA387 P particle (PP, P domain) and the S complex to synthetic oligosaccharides and saliva. (A) VP8* presented by the NoV P particle bound to the Leb oligosaccharides for both P[8] (Wa and DS1) and P[4] (RVP) RVs. (B) VP8* presented by the NoV S domain bound to the H type 1 in addition to the Leb antigens. (C and D) The bindings of VP8* to a panel of Leb-positive saliva samples were correlated with each other among the VP8* proteins presented by the NoV P particle (C) or the S domain (D).

The VP8* protein of P[6] RV recognizes the H type 1 antigen only.

We then extended the study to another major P type, P[6], of human RVs. Similar low binding activities of the free VP8* proteins (data not shown) and enhanced binding signals of the GST- and P particle-presented VP8* proteins were observed for two P[6] strains (BM11596 and ST3) studied. The binding patterns of the P[6] strains, however, differed from those of the P[4] and P[8] strains; the two P[6] strains bind the H type 1 antigen only without binding to the Leb antigen (Fig. 5). Surprisingly, the P[6] VP8* protein revealed only marginal binding activities with saliva samples even when the GST- and P particle-presented VP8* proteins of the two strains were tested (data not shown). To verify the result, a panel of Leb-negative saliva samples was studied. Although the binding signals were still low, a correlation with binding of VP8* to the salivary H type 1 antigen was noticed (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5.

Binding of VP8* from two P[6] RVs to synthetic oligosaccharides. The ST3 VP8*-GST fusion protein and the BM11596 VP8* core protein presented by the VA387 P domain (P particle, PP) were tested by the oligosaccharide binding assays described in Materials and Methods. Both BM11596 (A) and ST3 (B) recognized PAA-conjugated H type 1 only. (C) A panel of Lewis b-negative saliva samples was tested for binding to BM11596 VP8*. The data for individual saliva samples were sorted by their binding activities with the VP8* protein.

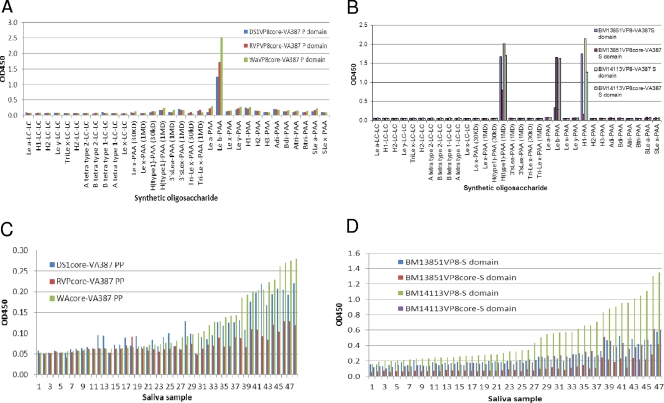

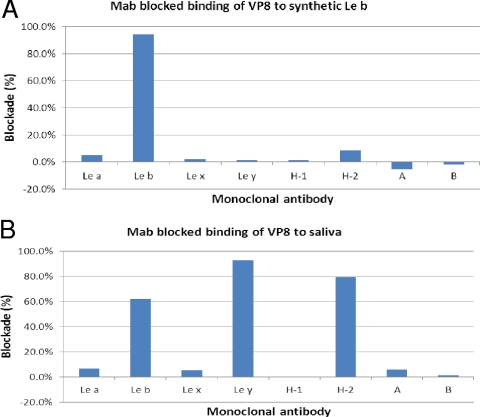

Validation of the binding specificity by HBGA-specific MAbs.

To further validate the binding specificity, we measured blocking effects of MAbs specific to variable HBGAs on the binding of the GST-VP8* fusion proteins to saliva and oligosaccharides. Only MAb specific to Leb but not to other HBGAs blocked binding of GST-VP8* of P[8] to synthetic oligosaccharide (Fig. 6A). The blockade of binding to saliva, however, seemed variable; MAbs against Ley and H type 2 in addition to Leb blocked binding of GST-VP8* to saliva (Fig. 6B). It is known that human saliva usually contains a mixture of different HBGAs, including ABO, Lewis, and secretor types, of which Leb, Ley, and H type 2 contain common α1,2-linked fucose that may complicate the experiment outcomes.

Fig 6.

Blocking of binding of RV VP8* to synthetic oligosaccharide (A) and saliva (B) by monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) specific for HBGAs. Microtiter plates were coated with Leb oligosaccharide (A) or Leb-positive saliva (B) to capture RV VP8*-GST fusion protein (∼10 μg/ml) with or without preincubation with MAbs (at a dilution of 1:20) against Lea, Leb, Lex, Ley, A, B, H type 1, and H type 2 antigens. VP8*-specific blocking activity was determined by the reduction (%) of the optical density values in wells with MAbs compared with those in wells without MAbs.

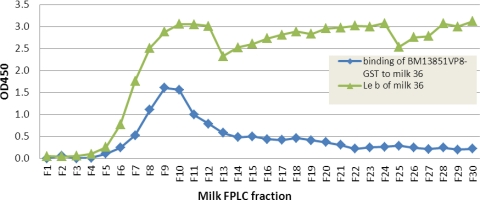

RV-VP8* also recognizes Leb in human milk.

In study of a panel of human milk samples, we observed specific binding of P[8] VP8* to secretor-positive milk (data not shown). We then performed binding assays using two milk samples following separation of the components in the milk samples through gel filtration. Again, the P[8] VP8* protein bound to the Leb-positive but not the Leb-negative milk sample (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Interestingly, the binding signals were mainly detected in fractions containing the high-molecular-weight (MW) molecules, similar to that observed in binding to NoVs that recognize only the high-MW mucin or mucin-like glycans (26).

Fig 7.

Binding of RV-VP8* to milk Leb antigen in size-exclusive FPLC fractions. Boiled FPLC fractions of one secretor's milk sample (milk 36) were used to coat microtiter plates at a dilution of 1:15 in 1× PBS. The bound BM13851 VP8*-GST protein was detected by rotavirus hyperimmune sera. Only the high-molecular-weight fractions containing Leb antigen showed binding. The distribution of milk Leb in the FPLC fraction was previously measured in a separate experiment.

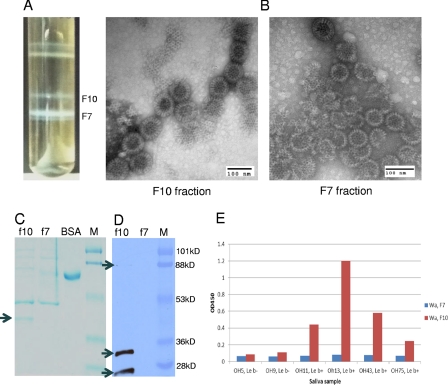

RV triple-layered particles bound HBGAs.

To further determine the biological relevance of the observed VP8*-HBGA interaction, virions of strain Wa were purified from cell cultures through a standard CsCl gradient. Evidence of double-layered particles (DLPs) and triple-layered particles (TLPs) was obtained by observation of typical DLPs and TLPs by electron microscopy (EM), by detection of additional VP7 and VP8* proteins in the TLP fraction but not in the DLP fraction by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses (Fig. 8), and by significantly higher (∼256 times) infectivity of the TLP fraction than of the DLP fraction. The highly purified Wa TLPs revealed specific binding to Leb-positive but not to Leb-negative secretor saliva samples (Fig. 8). In contrast, the CsCl gradient fraction containing DLPs did not reveal such binding activity with either the Leb-positive or the Leb-negative saliva samples, even when 4-fold more DLPs than TLPs were used. Our results suggest that HGBA binding ability is the authentic nature of RVs, and the spike protein VP8* on the outer layer of RVs is likely to be responsible for the binding function.

Fig 8.

Purification of Wa TLP and its binding to saliva samples from Leb-positive individuals. Wa TLP and DLP bands were observed in a CsCl gradient purification (A). DLPs (F7; density, 1.39 g/cm3 in CsCl) and TLPs (F10; density, 1.36 g/cm3 in CsCl) were confirmed by electron microscopy (EM) examination (B) and Western blot analysis (D). Typical TLPs and DLPs were observed in each of the two fractions by EM in negatively stained grids (B). SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining revealed an extra protein band (38 kDa) (arrow) in F10 but not in F7, which is predicted to be the VP7 protein on the outer layer of TLPs, missing on DLPs. The amounts of viral loading of F10 and F7 in the gels were adjusted to equality on the basis of the amounts of VP6 in each of the two fractions (C). The presence of the other major outer layer surface protein VP4 was confirmed by detection of VP4 (top arrow), the protease-processed VP8* protein (middle arrow), and a truncated VP8* protein (bottom arrow) by Western blot analysis using a VP8*-specific monoclonal antibody (D). Specific binding of the Wa TLPs, but not the DLPs, to the Leb HBGAs was demonstrated by the saliva-based binding assay using a panel of Leb-positive and -negative saliva samples (E). Equal volumes (10 μl) of F7 and F10 were used in the saliva binding assay. A serial dilution analysis by SDS-PAGE showed that the amount of the DLPs was ∼4-fold larger than that of the TLPs based on the intensities of the major structural protein VP6 in the two preps in the gel (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provided the first evidence of specific interactions between human RVs and HBGAs through the outer-layer spike protein VP8*. Two genetically closely related P genotypes (P[4] and P[8]) recognize the common Leb and H type 1 antigens, while a genetically more distantly related P genotype (P[6]) recognizes H type 1 only. These binding activities were confirmed by different forms of recombinant VP8*. The binding specificities have also been verified by binding and blocking experiments using saliva, synthetic oligosaccharide, human milk, and MAbs specific to variable HBGAs. Finally, the biological relevance of the observed VP8*-HBGA interaction was shown by the binding of authentic RVs to the Leb-positive saliva samples. These data suggested that the major P genotypes of RVs causing human acute gastroenteritis may recognize human HBGAs on host cells as attachment factors or receptors.

The requirement of a carbohydrate receptor appears to be a common feature of RVs. While some animal RVs have been shown to recognize the SA as receptors, our data in this study suggested that the human RVs may recognize the human HBGAs. This feature seems similar to what were found in caliciviruses. While the human caliciviruses, such as the human NoVs, recognize the human HBGAs, nonhuman caliciviruses, such as the murine NoVs and the feline calicivirus recognizing the SA as receptors, recognize other carbohydrates (51, 60). In a separate study, an additional HBGA binding pattern of RVs that recognizes the type A HBGAs by P[9] and P[14] RVs has been found (Y. Liu et al., submitted for publication). These data further suggested that the human HBGAs may play an important role in the infection of human RVs, although future studies for proving this hypothesis are necessary.

In the saliva- and oligosaccharide-based binding assays, we did not observe specific interaction of either P[4] or P[8] RVs with the SA-containing carbohydrate antigens, including sialyl Lea and sialyl Lex. This result is consistent with the notion that neither P[4] nor P[8] RVs recognize the terminal sialic acid (8, 9). However, whether any subterminal SAs on the host cells are involved in infection of these two genotypes remains unknown. Since the hypothesis of involvement of subterminal SAs in RV infection was mainly based on increased infectivity and binding of RV Wa following the sialidase treatment of the host cells, there could be other epitopes in addition to SA that are also involved. Indeed, structural analyses of RV VP8* suggested that other carbohydrates may be involved in RV host interaction by observing an additional carbohydrate binding pocket on RV VP8* (7, 43). Thus, future studies for elucidating the role of subterminal SA as well as other carbohydrate epitopes in the infection of these “sialidase-insensitive” human RVs are necessary.

The finding that the P[4], P[6], and P[8] human RVs recognize the major secretor epitopes of human HBGAs appears to correlate with the predominance of these genotypes of RVs over other genotypes in causing disease in different populations. The α1,2-fucose is the major determinant of the secretor antigens that is synthesized by the α1,2-fucosetransferase encoded by the FUT2 gene. Secretor antigens are present in ∼80% of the general population in the North American and European countries (33, 34) and possibly many other regions of the world as well. Thus, the high prevalence of these genotypes could be due to their interactions with wide spectrum of host HBGAs. In fact, >90% of the RV gastroenteritis cases were caused by P[8]- and P[4]-bearing RVs in many countries and for most years (13, 49). It is more interesting that the prevalences of the two P genotypes seemed always reciprocal to each other, with the P[8] genotype being predominant for most of years, according to surveillance data reported for Argentina, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Thailand (4–6, 13, 31, 32, 39, 40, 49). No such relationship was seen for P[6] RVs. These data suggested that the P[8] and P[4] RVs are competing with each other for commonly targeted populations of secretors.

The finding of P[6] RVs recognizing the H type 1 antigen also may explain their unique epidemic pattern. While much less common in many countries of the world, the P[6] RVs were significantly more common in the African countries (50, 54, 61, 62). In our previous studies of human HBGAs in different ethnic groups, the African-Americans appeared to have a significantly higher rate of the Lewis-negative secretor (H+ Lea−b−) phenotype than other ethnic groups (unpublished data). Genetically, these individuals do not have a functional Lewis gene and therefore can produce only H type 1, not Leb. Since the P[6] RVs bind H type 1 only, the higher prevalence of P[6] RVs in the African countries could be due to a higher rate of the Lea−b− phenotypes in these regions. However, high prevalence or endemicity of P[6] RVs has also been reported for India and for non-African newborn infants (3, 12, 30, 35). One report did not show association of secretor status with RV infection in children (1). Thus, future studies for clarifying these controversies by performing extended population studies in different countries and geographical locations are necessary.

In this study, we particularly studied recombinant VP8* proteins of RVs derived from stool samples of RV-infected patients. There was no difference between the HBGA binding profiles of these strains and those of cell culture-adapted strains, indicating that the observed HBGA binding was not an adapted property under the in vitro condition. We also studied multiple strains within each genotype and observed identical HBGA binding patterns among all strains within the same genotypes. In summary, the sialidase-insensitive human RVs may recognize the human HBGAs as an alternative attachment factor or as receptors, probably functionally similar to the terminal sialic acid for sialidase-sensitive animal RVs. The observed strain variations among different RV P genotypes suggest that further studies for exploring additional variations and the roles of HBGAs in RV infection and evolution are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dongsheng Zhang for valuable technical support and helpful discussion.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI37093 and R01 AI055649), the National Institute of Child Health (P01 HD13021), and the Department of Defense (PR033018). This study was also supported by an NIH/NIAID grant (1R21AI092434-01A1) to M.T.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 February 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahmed T, et al. 2009. Children with the Le(a+b-) blood group have increased susceptibility to diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli expressing colonization factor I group fimbriae. Infect. Immun. 77:2059–2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arias CF, et al. 2002. Molecular biology of rotavirus cell entry. Arch. Med. Res. 33:356–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahl R, et al. 2005. Incidence of severe rotavirus diarrhea in New Delhi, India, and G and P types of the infecting rotavirus strains. J. Infect. Dis. 192(Suppl. 1):S114–S119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beards G, Graham C. 1995. Temporal distribution of rotavirus G-serotypes in the West Midlands region of the United Kingdom, 1983–1994. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 13:235–237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beards GM, Desselberger U, Flewett TH. 1989. Temporal and geographical distributions of human rotavirus serotypes, 1983 to 1988. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2827–2833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bishop RF, Unicomb LE, Barnes GL. 1991. Epidemiology of rotavirus serotypes in Melbourne, Australia, from 1973 to 1989. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:862–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blanchard H, Yu X, Coulson BS, von Itzstein M. 2007. Insight into host cell carbohydrate-recognition by human and porcine rotavirus from crystal structures of the virion spike associated carbohydrate-binding domain (VP8*). J. Mol. Biol. 367:1215–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ciarlet M, Estes MK. 1999. Human and most animal rotavirus strains do not require the presence of sialic acid on the cell surface for efficient infectivity. J. Gen. Virol. 80(Pt. 4):943–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ciarlet M, et al. 2002. Initial interaction of rotavirus strains with N-acetylneuraminic (sialic) acid residues on the cell surface correlates with VP4 genotype, not species of origin. J. Virol. 76:4087–4095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clausen H, Hakomori S. 1989. ABH and related histo-blood group antigens; immunochemical differences in carrier isotypes and their distribution. Vox Sang. 56:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Das M, Dunn SJ, Woode GN, Greenberg HB, Rao CD. 1993. Both surface proteins (VP4 and VP7) of an asymptomatic neonatal rotavirus strain (I321) have high levels of sequence identity with the homologous proteins of a serotype 10 bovine rotavirus. Virology 194:374–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Das S, et al. 2004. Genetic variability of human rotavirus strains isolated from Eastern and Northern India. J. Med. Virol. 72:156–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Esteban LE, et al. 2010. Molecular epidemiology of group A rotavirus in Buenos Aires, Argentina 2004–2007: reemergence of G2P[4] and emergence of G9P[8] strains. J. Med. Virol. 82:1083–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiore L, Greenberg HB, Mackow ER. 1991. The VP8 fragment of VP4 is the rhesus rotavirus hemagglutinin. Virology 181:553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fukudome K, Yoshie O, Konno T. 1989. Comparison of human, simian, and bovine rotaviruses for requirement of sialic acid in hemagglutination and cell adsorption. Virology 172:196–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garduno RA, Brevik A, Benfield DA. 1997. Elucidating the cell entry mechanisms of porcine rotaviruses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 412:213–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graham KL, et al. 2003. Integrin-using rotaviruses bind alpha2beta1 integrin alpha2 I domain via VP4 DGE sequence and recognize alphaXbeta2 and alphaVbeta3 by using VP7 during cell entry. J. Virol. 77:9969–9978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guerrero CA, et al. 2000. Integrin alpha(v)beta(3) mediates rotavirus cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:14644–14649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hakomori S. 1999. Antigen structure and genetic basis of histo-blood groups A, B and O: their changes associated with human cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1473:247–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haselhorst T, et al. 2009. Sialic acid dependence in rotavirus host cell invasion. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5:91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henry S, Oriol R, Samuelsson B. 1995. Lewis histo-blood group system and associated secretory phenotypes. Vox Sang. 69:166–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Henry SM. 1996. Review: phenotyping for Lewis and secretor histo-blood group antigens. Immunohematology 12:51–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hewish MJ, Takada Y, Coulson BS. 2000. Integrins alpha2beta1 and alpha4beta1 can mediate SA11 rotavirus attachment and entry into cells. J. Virol. 74:228–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang P, et al. 2003. Noroviruses bind to human ABO, Lewis, and secretor histo-blood group antigens: identification of 4 distinct strain-specific patterns. J. Infect. Dis. 188:19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang P, et al. 2005. Norovirus and histo-blood group antigens: demonstration of a wide spectrum of strain specificities and classification of two major binding groups among multiple binding patterns. J. Virol. 79:6714–6722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang P, Morrow AL, Jiang X. 2009. The carbohydrate moiety and high molecular weight carrier of histo-blood group antigens are both required for norovirus-receptor recognition. Glycoconj. J. 26:1085–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isa P, Arias CF, Lopez S. 2006. Role of sialic acids in rotavirus infection. Glycoconj. J. 23:27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Isa P, Realpe M, Romero P, Lopez S, Arias CF. 2004. Rotavirus RRV associates with lipid membrane microdomains during cell entry. Virology 322:370–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang X, et al. 2004. Human milk contains elements that block binding of noroviruses to human histo-blood group antigens in saliva. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1850–1859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kang JO, Kim CR, Kilgore PE, Choi TY. 2006. G and P genotyping of human rotavirus isolated in a university hospital in Korea: implications for nosocomial infections. J. Korean Med. Sci. 21:983–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khamrin P, et al. 2007. Changing pattern of rotavirus G genotype distribution in Chiang Mai, Thailand from 2002 to 2004: decline of G9 and reemergence of G1 and G2. J. Med. Virol. 79:1775–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kirkwood C, et al. 2002. Report of the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program, 2001/2002. Commun. Dis. Intell. 26:537–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le Pendu J. 2004. Histo-blood group antigen and human milk oligosaccharides: genetic polymorphism and risk of infectious diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 554:135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Le Pendu J, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Kindberg E, Svensson L. 2006. Mendelian resistance to human norovirus infections. Semin. Immunol. 18:375–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Linhares AC, et al. 2002. Neonatal rotavirus infection in Belem, northern Brazil: nosocomial transmission of a P[6] G2 strain. J. Med. Virol. 67:418–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lopez JA, et al. 2005. Characterization of neuraminidase-resistant mutants derived from rotavirus porcine strain OSU. J. Virol. 79:10369–10375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maass DR, Atkinson PH. 1990. Rotavirus proteins VP7, NS28, and VP4 form oligomeric structures. J. Virol. 64:2632–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marionneau S, et al. 2001. ABH and Lewis histo-blood group antigens, a model for the meaning of oligosaccharide diversity in the face of a changing world. Biochimie 83:565–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Masendycz P, Bogdanovic-Sakran N, Kirkwood C, Bishop R, Barnes G. 2001. Report of the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program, 2000/2001. Commun. Dis. Intell. 25:143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Masendycz P, Bogdanovic-Sakran N, Palombo E, Bishop R, Barnes G. 2000. Annual report of the Rotavirus Surveillance Programme, 1999/2000. Commun. Dis. Intell. 24:195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mendez E, Arias CF, Lopez S. 1993. Binding to sialic acids is not an essential step for the entry of animal rotaviruses to epithelial cells in culture. J. Virol. 67:5253–5259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mendez E, Lopez S, Cuadras MA, Romero P, Arias CF. 1999. Entry of rotaviruses is a multistep process. Virology 263:450–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Monnier N, et al. 2006. High-resolution molecular and antigen structure of the VP8* core of a sialic acid-independent human rotavirus strain. J. Virol. 80:1513–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Padilla-Noriega L, Dunn SJ, Lopez S, Greenberg HB, Arias CF. 1995. Identification of two independent neutralization domains on the VP4 trypsin cleavage products VP5* and VP8* of human rotavirus ST3. Virology 206:148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patton JT, Hua J, Mansell EA. 1993. Location of intrachain disulfide bonds in the VP5* and VP8* trypsin cleavage fragments of the rhesus rotavirus spike protein VP4. J. Virol. 67:4848–4855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pesavento JB, Crawford SE, Roberts E, Estes MK, Prasad BV. 2005. pH-induced conformational change of the rotavirus VP4 spike: implications for cell entry and antibody neutralization. J. Virol. 79:8572–8580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ruggeri FM, Greenberg HB. 1991. Antibodies to the trypsin cleavage peptide VP8 neutralize rotavirus by inhibiting binding of virions to target cells in culture. J. Virol. 65:2211–2219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rydell GE, et al. 2009. Human noroviruses recognize sialyl Lewis x neoglycoprotein. Glycobiology 19:309–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Santos N, Hoshino Y. 2005. Global distribution of rotavirus serotypes/genotypes and its implication for the development and implementation of an effective rotavirus vaccine. Rev. Med. Virol. 15:29–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Seheri LM, et al. 2010. Characterization and molecular epidemiology of rotavirus strains recovered in Northern Pretoria, South Africa during 2003–2006. J. Infect. Dis. 202(Suppl.):S139–S147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stuart AD, Brown TD. 2007. Alpha2,6-linked sialic acid acts as a receptor for Feline calicivirus. J. Gen. Virol. 88:177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suzuki H, Kitaoka S, Konno T, Sato T, Ishida N. 1985. Two modes of human rotavirus entry into MA 104 cells. Arch. Virol. 85:25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Suzuki H, et al. 1986. Further investigation on the mode of entry of human rotavirus into cells. Arch. Virol. 91:135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tamburlini G, Cattaneo A, Monasta L. 2010. Rotavirus vaccine efficacy in African and Asian countries. Lancet 376:1897 (author's reply, 376:1898) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. 2004. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J. Virol. 78:6233–6242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tan M, et al. 2011. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. J. Virol. 85:753–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tan M, Jiang X. 2011. Norovirus-host interaction: multi-selections by the human HBGAs. Trends Microbiol. 19:382–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tan M, Jiang X. 2005. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J. Virol. 79:14017–14030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tan M, Meller J, Jiang X. 2006. C-terminal arginine cluster is essential for receptor binding of norovirus capsid protein. J. Virol. 80:7322–7331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Taube S, et al. 2009. Ganglioside-linked terminal sialic acid moieties on murine macrophages function as attachment receptors for murine noroviruses. J. Virol. 83:4092–4101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Todd S, Page NA, Steele AD, Peenze I, Cunliffe NA. 2010. Rotavirus strain types circulating in Africa: Review of studies published during 1997–2006. J. Infect. Dis. 202(Suppl.):S34–S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Waggie Z, Hawkridge A, Hussey GD. 2010. Review of rotavirus studies in Africa: 1976–2006. J. Infect. Dis. 202(Suppl.):S23–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Willoughby RE, Yolken RH. 1990. SA11 rotavirus is specifically inhibited by an acetylated sialic acid. J. Infect. Dis. 161:116–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yolken RH, Willoughby R, Wee SB, Miskuff R, Vonderfecht S. 1987. Sialic acid glycoproteins inhibit in vitro and in vivo replication of rotaviruses. J. Clin. Invest. 79:148–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zarate S, et al. 2000. Integrin alpha2beta1 mediates the cell attachment of the rotavirus neuraminidase-resistant variant nar3. Virology 278:50–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]