Abstract

The causative agent of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, possesses a segmented genome comprised of a single linear chromosome and upwards of 23 linear and circular plasmids. Much of what is known about plasmid-borne genes comes from studying laboratory clones that have spontaneously lost one or more plasmids during in vitro passage. Some plasmids, including the linear plasmid lp17, are never or rarely reported to be lost during routine culture; therefore, little is known about the requirement of these conserved plasmids for infectivity. In this study, the effects of deleting regions of lp17 were examined both in vitro and in vivo. A mutant strain lacking the genes bbd16 to bbd25 showed no deficiency in the ability to establish infection or disseminate to the bloodstream of mice; however, colonization of peripheral tissues was delayed. Despite the ability to colonize ear, heart, and joint tissues, this mutant exhibited a defect in bladder tissue colonization for up to 56 days postinfection. This phenotype was not observed in immunodeficient mice, suggesting that bladder colonization by the mutant strain was inhibited by an adaptive immune-based mechanism. Moreover, the mutant displayed increased expression of outer surface protein C in vitro, which was correlated with the absence of the gene bbd18. To our knowledge, this is the first report involving genetic manipulation of lp17 in an infectious clone of B. burgdorferi and reveals for the first time the effects of lp17 gene deletion during murine infection by the Lyme disease spirochete.

INTRODUCTION

The causative agent of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, is an obligate parasite that is maintained in nature through an enzootic cycle involving a tick vector and mammalian host (10, 33, 55). B. burgdorferi has an unusual segmented genome comprised of a 910-kb linear chromosome and upwards of 23 linear and circular plasmids ranging in size from 5 to 56 kb (12, 21, 39, 56). The majority of predicted plasmid-borne open reading frames (ORFs) encode genes of unknown function, and their potential roles in transmissibility, colonization, dissemination, and persistence in the mammalian host have yet to be determined.

Much of what is known about the requirement of plasmid-borne genes for infectivity in the mammalian host is derived from studies using clonal isolates that have spontaneously lost one or more plasmids during in vitro cultivation and determining the ability of these mutant clones to infect mice in the laboratory (29, 32, 40, 48, 53, 63). Selective displacement of B. burgdorferi plasmids through the introduction of incompatible shuttle vectors has also been used as a technique to assess the contribution of certain plasmids to virulence (18, 23).

The loss of several linear plasmids in particular, including lp25, lp28-1, and lp36, has been associated with a loss of infectivity of B. burgdorferi (23, 28, 31, 32, 48). Further studies have localized these effects to specific virulence determinant genes carried on these plasmids, demonstrating the importance of plasmid-borne genes for both B. burgdorferi pathogenesis and physiological functions in vivo (3, 47, 57). Despite the importance of some B. burgdorferi plasmids for murine infection, clones lacking other plasmids, including cp9, lp5, lp21, lp28-4, lp38, and lp56, have been shown to be fully infectious in mice, illustrating the variable requirement of B. burgdorferi plasmids for infectivity in the mouse host (18, 29, 32, 48).

While analysis of plasmid loss among B. burgdorferi isolates has been an invaluable strategy for assessing the contribution of plasmid-borne genes to infectivity, some plasmids are never or rarely reported to be spontaneously lost during routine culture. Therefore, limited information about the requirement of these conserved plasmids for infectivity is available. One such plasmid, lp17, is a 16,823-bp linear plasmid carrying 25 putative ORFs (21). While lp17 has occasionally been reported to be lost after extended in vitro passage (24, 41, 50), this plasmid was not reported to be lost in prior studies correlating plasmid loss with infectivity (18, 23, 29, 32, 40, 48, 53, 63).

To date, lp17 has been primarily utilized as a tool to examine the mechanism of linear DNA replication in B. burgdorferi (5, 13). Using targeted plasmid deletion, the majority of this plasmid has been shown not to be required for viability in the noninfectious strain B31-A; however, a role for lp17 during infectivity or persistence has not been evaluated in an infectious background. Recently, many of the genes on lp17 have been shown to undergo changes in expression under culture conditions that mimic either the tick vector or the mammalian host (1, 9, 38, 42, 58). Further studies using mutant strains lacking alternative sigma factors involved in regulating the expression of host-specific genes showed similar alterations in the expression levels of lp17-borne genes (7, 11, 43, 44, 49). During the course of the current study, Sarkar et al. demonstrated that expression of the lp17-borne bbd18 gene inversely correlated with expression of outer surface protein C (ospC) in a noninfectious strain of B. burgdorferi (52). These previous studies combined with the relative lack of knowledge about the involvement of this plasmid during mammalian infection make lp17 an interesting target for further analysis during the infectious cycle.

In the present study, the effect of lp17 gene deletion on infectivity and persistence in the murine host was examined. Deletion of ORFs bbd16 to bbd25 did not affect the ability of B. burgdorferi to establish initial infection in mice or to disseminate from the site of infection to the bloodstream. However, the mutant demonstrated a delayed ability to colonize all peripheral tissues examined and continued to exhibit reduced bladder colonization for up to 56 days postinfection (p.i.). This strain displayed an increased expression of OspC in vitro, which correlated with the absence of the gene bbd18. Collectively, these results demonstrate a role for lp17 during mammalian infection and strongly support the contribution of this plasmid to the regulation of OspC expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and DNA isolation.

The B. burgdorferi isolates B31-A and B31-5A4 (5A4) were kindly provided by George Chaconas via gifts from Patti Rosa and Steven Norris, respectively. Both are clones of the sequenced B31 type strain (21), and their respective infectivities and plasmid profiles have been previously described (8, 48). These B. burgdorferi isolates were used to generate all mutant clones in this study, as described below. All B. burgdorferi clones were grown at 35°C in modified Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium (BSK-II) supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (4). Mutant strains were grown with kanamycin (200 μg/ml) or gentamicin (100 μg/ml), as indicated. Cell densities and growth phase were monitored by visualization under dark-field microscopy and counting using a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from B. burgdorferi cultures using a plasmid midikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for further analysis and/or use as the PCR template.

Plasmid construction.

The deletion plasmid, pYT1014, was generated through the replacement of the original deletion target region from the previously described construct pYT1 with DNA corresponding to coordinates 9188 to 10113 of lp17 (60). A 1,214-bp region of lp17 was PCR amplified from 5A4 plasmid DNA using primers P43 (5′-CAAATGACTTTTATGAAATTTGG-3′) and P44 (5′-GGAAACATCTATCTGCTTTATG-3′) and subsequently cloned into the vector pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The resulting construct was digested with the restriction endonuclease EcoRI, in order to recover the 925-bp target region. The discrepancy in size between the original PCR product and the purified target region was due to the presence of an internal EcoRI site in the cloned DNA fragment, which did not affect the desired lp17 deletion.

The left-end-deletion construct, pYT1013F, was generated in a similar manner, using primers P41 (5′-TCACATTATTGTAATTTTTTTTTG-3′) and P42 (5′-GTGAACTTCTACTAACTTGTTTGC-3′) in order to amplify the target region. In this instance, despite an internal EcoRI site within the PCR product, full-length target was recovered through partial EcoRI digestion and subsequent screening.

After isolation and purification, lp17 target regions were ligated into EcoRI-digested pYT1 and transformed into Escherichia coli. Plasmids isolated from individual E. coli clones were screened by restriction digestion to confirm the presence and correct orientation of the deletion targets.

Complementing plasmids were constructed by PCR amplification of the target gene, including its putative native promoter, and cloned into pBSV2G (19) at a unique SalI recognition site (introduced SalI sites are indicated in bold, as shown below). The bbd18 complement was constructed by PCR amplification of bbd18, including 409 bp of upstream sequence and 50 bp of downstream sequence, from 5A4 plasmid DNA using the primers P209 (5′-GCTCGTCGACAAATATTATTTAATAATAATAAATAAAATTAAACG-3′) and P210 (5′-ATCAGTCGACCAGAATTTACTTACAATATTTAACCTTC-3′). The bbd21 complement was constructed by PCR amplification of bbd21, including 363 bp of upstream sequence and 50 bp of downstream sequence, using the primers P211 (5′-ATCAGTCGACGCTTGTTAATCATGCTATTG-3′) and P212 (5′-GCTCGTCGACGTAGATAATTCTTTATTATTTTTTTG-3′).

Mutant generation and screening.

All transformations were performed using electrocompetent B. burgdorferi prepared and cultivated as previously described (3, 51). Transformed bacteria were recovered for 24 h and plated by limiting dilution with antibiotic selection to isolate clonal transformants. Deletion mutants were initially identified by PCR screening for the kanamycin resistance gene using primers P54 (5′-CATATGAGCCATATTCAACGGGAAACG-3′) and P55 (5′-AAAGCCGTTTCTGTAATGAAGGAG-3′) (8). Clones positive for the kanamycin resistance gene were further analyzed by field inversion gel electrophoresis and Southern blot analysis to confirm the desired deletion and the absence of the parent plasmid. The bbd18- and bbd21-complemented strains were confirmed in a similar manner, utilizing primers P91 (5′-CGCAGCAGCAACGATGTTAC-3′) and P92 (5′-CTTGCACGTAGATCACATAAGC-3′) to screen for the gentamicin resistance gene by PCR (59). Prior to mouse studies, B. burgdorferi plasmid content was analyzed by PCR with primers specific for regions unique to each plasmid, as previously described (48, 59).

In vitro growth assays.

B. burgdorferi was grown to late log phase and subcultured to a density of 105 cells/ml. Cell densities were determined at 24-h intervals and expressed as the mean number of cells from three experiments ± standard deviation. Mean values for wild-type and mutant clones were compared at each time point using Student's t test. To compare overall stationary-phase cell densities, values from days 9 to 13 were pooled prior to analysis. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant where P was <0.05. Data were analyzed and displayed using the SigmaPlot (version 11) program (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

Infection and recovery of B. burgdorferi from mice.

All animal infections were carried out in accordance with approved protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Washington State University (Animal Safety Approval Form 3729). Four-week-old male C3H/HeN (C3H; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) and C3SnSmn.CB17-Prkdcscid/J (SCID; Jackson, Bar Harbor, ME) mice were infected by both intraperitoneal (91% of infectious dose) and subcutaneous (9% of infectious dose) needle inoculation of 100 μl BSK-II containing the indicated number of B. burgdorferi cells. Blood, ear, heart, bladder, and joint tissues were collected at the indicated times and cultured in BSK-II supplemented with 20 μg/ml phosphomycin, 50 μg/ml rifampin, and 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B. Dark-field microscopy was used to determine the presence or absence of viable spirochetes for each cultured tissue sample. A sample was deemed negative if no spirochetes could be seen in 10 fields of view after 4 weeks of culture.

Protein analysis.

Total B. burgdorferi cellular proteins were resolved using SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Either gels were stained directly with Coomassie brilliant blue or proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting. Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) supplemented with 5% nonfat milk, followed by immunoblotting (1 h, room temperature) in TBST with primary antisera, as indicated. Primary antibody included mouse anti-5A4 sera (1:1,000), rabbit anti-FlaB (1:1,000; Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA), and rabbit anti-OspC (1:1,000; Rockland Immunochemicals). After a series of washes, all samples were then probed with the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:5,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), washed, and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence.

For identification of unknown protein, proteins were resolved using 4% to 20% precast Tris-HCl Ready Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and stained directly using Coomassie brilliant blue. The band of interest was excised and destained, and gel slices containing the target protein were sent to the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core Analytical Facility at the University of Idaho for further processing and analysis using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Proteins corresponding to the identified peptides were determined by searching the Swiss-Prot protein database using Protein Lynx Global Server software (Waters Corp., Milford, MA).

RESULTS

The left and right ends of lp17 display different requirements for viability of 5A4 in vitro.

Previous work by Beaurepaire and Chaconas localized the essential region of replication on lp17 to a segment of the plasmid from coordinates 7946 to 9766 containing a single intact gene, bbd14, in addition to some adjacent noncoding sequence (5). All of the predicted ORFs upstream or downstream (or left and right, respectively) of this region were successfully deleted from lp17, yielding viable mutant clones in vitro in the noninfectious isolate B31-A. In the present study, the effects of lp17 gene deletion on both in vitro viability and in vivo infectivity were examined in the infectious B. burgdorferi clone 5A4, which contains the full complement of parent plasmids reported in the sequenced B31 isolate (21, 48).

In order to generate left- and right-end lp17 mutants in 5A4, a targeted deletion strategy was utilized (Fig. 1) (3, 5, 13). Briefly, this approach involves the introduction of a replicated telomere at any position within a linear plasmid via integration of a deletion construct at a target site for homologous recombination. Deletion construct integration is followed by recognition and processing of the introduced internal replicated telomere by the endogenous B. burgdorferi protein ResT (30). Telomere resolution by ResT leads to the production of a new covalently closed hairpin end, resulting in deletion of the entire plasmid region located upstream or downstream of the target sequence.

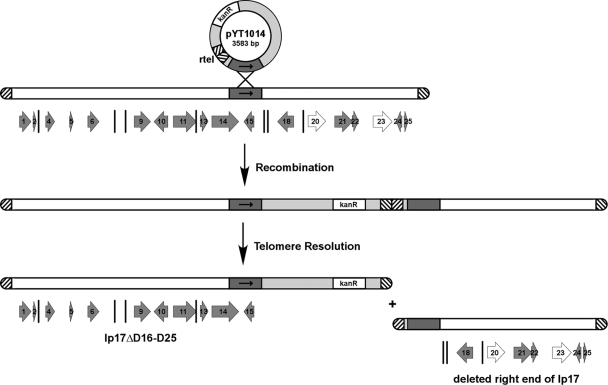

Fig 1.

Targeted deletion of bbd16 to bbd25 on lp17. An E. coli plasmid, pYT1014 (light gray), containing a target region of lp17 (arrow, dark gray), a 50-bp replicated telomere (rtel, hatched lines), and a kanamycin resistance gene (kanR, white) was generated and used to transform B. burgdorferi 5A4. Insertion of the plasmid construct occurs at the target site through a process of homologous recombination. Deletion of lp17 to the right of the target sequence, including ORFs bbd16 to bbd25, follows a telomere resolution event at the replicated telomere. The remaining truncated form of lp17 (lp17ΔD16-D25) is maintained due to the presence of the replication initiator bbd14 and confers kanamycin resistance due to the presence of the integrated deletion construct. The 25 predicted ORFs of lp17 are numbered according to their gene designation and depicted as large gray arrows where size allows, with the smallest ORFs indicated by vertical lines only. The two ORFs containing authentic frameshift mutations, bbd20 and bbd23, are represented as white arrows.

To generate an lp17 right-end deletion, the plasmid pYT1014 was constructed (see Materials and Methods). This plasmid contains a kanamycin resistance gene, a replicated telomere, and a region of target DNA homologous to lp17 corresponding to a portion of bbd14-bbd15 (Fig. 1). Strain 5A4 was transformed with this construct, and clones were isolated under kanamycin selection. As shown in Fig. 1, integration of pYT1014 into lp17 results in insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene and the loss of all genes downstream of the target region, specifically, bbd16 to bbd25. Clones containing the desired mutation were initially identified by PCR screening for the kanamycin resistance gene and confirmed by visualization of total plasmid DNA separated by field inversion gel electrophoresis and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). The mutant clone (denoted 5A4ΔD16-D25) was found to have retained all B. burgdorferi parent plasmids, as determined by PCR analysis (data not shown).

A second deletion construct, pYT1013F, was generated to target the lp17 left-end genes bbd01 to bbd11 for removal (see Fig. 1 for lp17 gene arrangement). Numerous attempts at deletion of these genes in wild-type 5A4 were unsuccessful. To confirm that the plasmid construct was functional, pYT1013F was tested in the B31-A background as previously described (5), successfully producing the desired lp17 deletion mutant (data not shown). Additionally, the previously described deletion construct pYT1 (60), which targets the extreme left-end genes bbd01 to bbd04 for deletion, was capable of generating the desired mutation in both B31-A and 5A4 (data not shown).

Collectively, these results demonstrate that bbd16 to bbd25 are not required for in vitro survival of the infectious B. burgdorferi clone 5A4, which possesses the full complement of parent plasmids. Despite the ability to generate mutations in both the left and right ends of lp17 in 5A4 (as demonstrated using pYT1 Δbbd01-bbd04 and pYT1014 Δbbd16-bbd25, respectively), attempts at deleting bbd01 to bbd11 did not yield viable clones, suggesting a more stringent in vitro requirement for this region. The inability to delete the region containing bbd01 to bbd11 appears to be clone specific, as mutant clones were obtained in the noninfectious isolate B31-A. The phenotypic effects of the deletion of genes bbd16 to bbd25 were further examined both in vitro and in vivo.

B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 shows impaired growth in vitro.

Both 5A4ΔD16-D25 and the wild-type control strain were grown in liquid BSK-II to determine how the loss of bbd16 to bbd25 affects growth during in vitro cultivation. 5A4ΔD16-D25 showed a significantly lower cell density than 5A4 at all time points (P < 0.03 for all), with the exception of day 1 postdilution, whereby the observed difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.054) (Fig. 2). In addition to decreased cell densities at time points throughout the exponential phase of growth, 5A4ΔD16-D25 showed a reduced maximum cell density during stationary phase (5.85 × 107 ± 1.41 × 107 cells/ml) compared to wild-type 5A4 (1.33 × 108 ± 2.51 × 107 cells/ml) (P < 0.001).

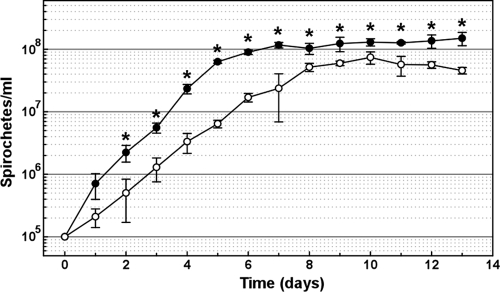

Fig 2.

Deletion of bbd16 to bbd25 leads to decreased growth in vitro. Average number of spirochetes/ml (n = 3) in liquid BSK-II of wild-type 5A4 (black circles) and mutant 5A4ΔD16-D25 (open circles) at the indicated time points. The mutant strain demonstrated a decreased cell density compared to 5A4 at all time points from day 2 to day 13 after the initial subculture. Standard deviations from the mean are indicated by vertical bars. Means were compared at each time point using Student's t test, and statistically significant differences between wild-type and mutant clones are denoted by asterisks (P < 0.05).

Similarly, swarming ability on semisolid BSK-II agarose plates was reduced for 5A4ΔD16-D25 compared to the wild-type strain (data not shown), likely due to differences in growth between the two strains upon plating. These results suggest that B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 is somewhat impaired in its ability to replicate in vitro.

Deletion of bbd16 to bbd25 leads to altered tissue colonization during infection of C3H mice.

In order to examine phenotypic differences in the ability of the mutant strain to infect mice, two groups of 15 C3H mice were needle inoculated with 1.1 × 104 spirochetes of either 5A4 or 5A4ΔD16-D25. Each group of 15 mice was further divided into three groups of five mice (denoted group 1, group 2, and group 3) in order to track infection, as shown in Fig. 3.

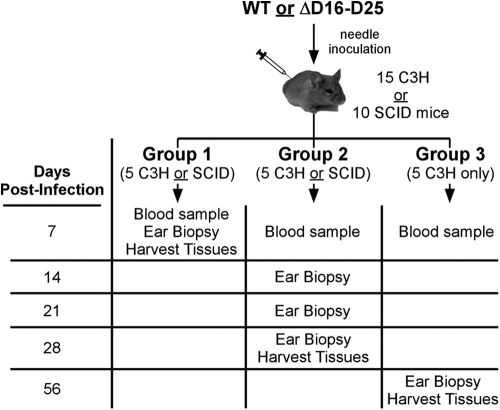

Fig 3.

Sampling protocol to monitor mouse infection with B. burgdorferi. Groups of either 15 C3H or 10 SCID mice were infected by needle inoculation with wild-type strain 5A4 (WT) or the mutant strain (ΔD16-D25). Infected mice were further divided into groups of five mice each (denoted group 1, group 2, and group 3) as indicated. Blood samples were isolated from all mice at day 7 p.i. and cultured in BSK-II for the presence of spirochetes to confirm initial infection. Infection was tracked by culturing ear biopsy specimens obtained at the indicated times. Finally, mice were sacrificed for harvesting of tissues (heart, bladder, joint) at the indicated time points.

At day 7 p.i., blood was collected from all mice and cultured for the presence of spirochetes. Additionally, group 1 mice were sacrificed and ear, bladder, and joint tissues were isolated and cultured. Spirochetes were successfully cultured from the blood of all mice infected with either 5A4 or 5A4ΔD16-D25, indicating that bbd16 to bbd25 are not required for establishing initial infection or disseminating from the inoculation site to the bloodstream (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tissue distribution of B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 in C3H mice

| Tissue | No. of culture-positive samples/total no. of samples with the following challenge straina: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5A4 |

5A4ΔD16-D25 |

|||||

| Group 1 (7)b | Group 2 (28) | Group 3 (56) | Group 1 (7) | Group 2 (28) | Group 3 (56) | |

| Blood (day 7 p.i.) | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Ear | 1/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Heart | NAc | 5/5 | 5/5 | NA | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Bladder | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Joint | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Totald | 11/15 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 1/15 | 15/20 | 15/20 |

C3H mice were infected with 1.1 × 104 spirochetes of the indicated strain as described in Materials and Methods. See Fig. 3 for sampling protocol of mouse groups. Fifteen mice were tested with each challenge strain, and all 15 mice were infected.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the day p.i. at which mice were sacrificed and the ear, heart, bladder, and joint tissues were isolated for culture in BSK-II.

NA, heart tissue was not sampled at day 7 p.i., as culture results are confounded due to the presence of infected blood.

Total positive ear, heart, bladder, and joint cultures.

All bladder and joint tissues of group 1 mice infected with wild-type 5A4 were culture positive for spirochetes, whereas 5A4ΔD16-D25 was not recovered from any joint tissues and was successfully recovered from the bladder tissue of only one mouse (Table 1). The reduced ability to recover the mutant strain from bladder or joint tissues at day 7 p.i. suggests that bbd16 to bbd25 may be required for early dissemination and/or colonization of tissues. With the exception of one 5A4-infected mouse, ear biopsy specimens from all group 1 mice were culture negative regardless of the infecting strain type.

Infection was tracked weekly in group 2 mice over a 4-week period by culturing ear biopsy specimens (days 14, 21, and 28 p.i.), as well as heart, bladder, and joint tissues (day 28 p.i.). Ear tissues from all group 2 mice infected with wild-type 5A4 were culture positive at all time points, consistent with previous infection studies using this strain (Table 2) (3). In contrast, spirochetes were not recovered from ear tissues from any group 2 mice infected with 5A4ΔD16-D25 collected at day 14 p.i., and only 3/5 ear biopsy specimens were culture positive at day 21 p.i. At day 28 p.i., all five mice infected with 5A4ΔD16-D25 were culture positive for spirochetes from ear tissue. This timeline analysis of ear colonization in group 2 mice demonstrates that spirochetes lacking bbd16 to bbd25 are capable of disseminating from the bloodstream and colonizing ear tissue; however, their ability to do so is delayed.

Table 2.

Timeline analysis of infection by B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 in group 2 C3H mice

| Tissuea | No. of culture-positive samples/total no. of samples with the following challenge strainb: |

|

|---|---|---|

| 5A4 | 5A4ΔD16-D25 | |

| Blood (7) | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Ear (14) | 5/5 | 0/5 |

| Ear (21) | 5/5 | 3/5 |

| Ear (28) | 5/5 | 5/5 |

Ear tissue was isolated for culture in BSK-II at the day p.i. indicated in parentheses.

See Fig. 3 for sampling protocol of group 2 mice. C3H mice were infected with 1.1 × 104 spirochetes of the indicated strain as described in Materials and Methods.

Interestingly, although wild-type strain 5A4 was recovered from all tissue types at day 28 p.i. in group 2 mice, 5A4ΔD16-D25 was found only in ear, heart, and joint tissues and was not recovered from the bladder of any of the infected group 2 mice (Table 1). A similar difference in tissue colonization was observed with group 3 mice when infection was allowed to progress for 56 days prior to harvesting of tissues for bacterial culture (Table 1), indicating that this phenotype is not restricted to early infection. Additionally, bladder tissues collected at day 28 p.i. were culture negative for the mutant strain when the infectious dose was increased 10-fold to 1.1 × 105 bacterial cells per mouse (data not shown). Taken together, the above-described results demonstrate that although B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 shows delayed dissemination/colonization of tissues, this mutant strain is capable of colonizing and persisting in ear, heart, and joint tissues for up to 8 weeks p.i. In contrast, bbd16 to bbd25 are required for successful colonization of bladder tissue in C3H mice to the wild-type level, as determined by the ability to recover live spirochetes.

The minimum dose required for infection by a pathogenic organism can be used as an indicator of the ability to evade the host's initial defense mechanisms. In order to determine whether loss of bbd16 to bbd25 resulted in an altered efficiency of infection, groups of five mice were challenged with 10-fold serial dilutions of either 5A4 or 5A4ΔD16-D25. At 28 days p.i., mice were sacrificed and ear, heart, bladder, and joint tissues were cultured for the presence of spirochetes to determine successful infection as well as potential differences in tissue colonization. Spirochetes were successfully recovered from all mice inoculated with a dose of either 1.1 × 104 or 1.1 × 103 cells of the wild-type or mutant strain, and the differential ability to colonize bladder tissue between the two strains as described above was observed at both infectious doses (Table 3). All tissue types from all mice receiving an inoculation of 1.1 × 102 organisms of either strain were culture negative, with the exception of one 5A4ΔD16-D25-infected mouse that was successfully infected. These results indicate that loss of bbd16 to bbd25 does not significantly alter the number of spirochetes required to establish infection in mice.

Table 3.

Minimum infectious dose of B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 in C3H mice

| Tissue | No. of culture-positive samples/total no. of samples with the following challenge strain at the indicated challenge dosea: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5A4 |

5A4ΔD16-D25 |

|||||

| 102 | 103 | 104 | 102 | 103 | 104 | |

| Ear | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Heart | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Bladder | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Joint | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| No. of infected mice/total no. of mice | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 1/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

C3H mice were infected with indicated B. burgdorferi strain as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were sacrificed at 28 days p.i., and ear, heart, bladder, and joint tissues were isolated for culture in BSK-II. The challenge dose is in number of cells per mouse × 0.91.

The deficiency in bladder colonization exhibited by 5A4ΔD16-D25 is dependent on an adaptive immune response.

In order to investigate the involvement of the murine adaptive immune response in the observed B. burgdorferi mutant phenotypes, two groups of 10 SCID mice were needle inoculated with 1.1 × 104 spirochetes of either clone 5A4 or clone 5A4ΔD16-D25. Each group of 10 mice was further divided into two groups of five mice (denoted group 1 and group 2) in order to track infection, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Consistent with the results seen in C3H mice, spirochetes were recovered from the blood of all SCID mice infected with either the mutant or wild-type control strain (Table 4). Ear, bladder, and joint tissues harvested at day 7 p.i. from group 1 SCID mice also showed a similar pattern of tissue colonization seen with C3H mice. Spirochetes were recovered from 9 out of the 10 5A4-infected bladder and joint tissues tested, with one joint tissue specimen being culture negative (Table 4). In contrast, only one 5A4ΔD16-D25-infected joint tissue specimen was culture positive, while all other mutant-infected tissues were culture negative. Ear tissue was not a consistent source of spirochetes from either strain at day 7 p.i., with only one 5A4-infected ear tissue sample being culture positive. These results indicate that the deficiency in early tissue colonization by 5A4 lacking bbd16 to bbd25 is not dependent on a functional adaptive immune system.

Table 4.

Tissue distribution of B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 in SCID mice

| Tissue | No. of culture-positive samples/total no. of samples with the following challenge straina: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5A4 |

5A4ΔD16-D25 |

|||

| Group 1 (7)b | Group 2 (28) | Group 1 (7) | Group 2 (28) | |

| Blood | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Ear | 1/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 |

| Heart | NAc | 5/5 | NA | 5/5 |

| Bladder | 5/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 |

| Joint | 4/5 | 5/5 | 1/5 | 5/5 |

| Totald | 10/15 | 20/20 | 1/15 | 20/20 |

SCID mice were infected with 1.1 × 104 spirochetes of the indicated strain as described in Materials and Methods. See Fig. 3 for sampling protocol of mouse groups. Ten mice were tested with each challenge strain, and all 10 mice were infected.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the day p.i. at which mice were sacrificed and ear, heart, bladder, and joint tissues were isolated for culture in BSK-II.

NA, heart tissue was not sampled at day 7 pi, as culture results are confounded due to the presence of infected blood.

Total positive ear, heart, bladder, and joint cultures.

In contrast, the defect in bladder colonization observed at day 28 p.i. for the mutant in C3H mice was not observed in SCID mice, as both wild-type and mutant strains were recovered from all tissue types of all group 2 SCID mice (Table 4). The detectable presence of live mutant spirochetes in the bladder tissues of SCID mice but not C3H mice suggests that the reduced ability of 5A4ΔD16-D25 to colonize the bladder is due to the presence of a murine adaptive immune response.

Deletion of bbd16 to bbd25 leads to altered in vitro expression of the known surface immunogen OspC.

The dependency of the observed differences in bladder colonization on the presence of an adaptive immune system suggested a possible change in the expression of surface immunogens. The in vitro protein expression profiles of both 5A4 and 5A4ΔD16-D25 were examined to address this possibility. The two strains were lysed in order to obtain proteins for analysis by SDS-PAGE. Both Coomassie-stained gels and anti-5A4 Western blots showed similar protein expression profiles between strains, with one notable exception. An additional band corresponding to a protein of approximately 20 kDa in size was visible in lysates from the mutant strain but was not detectable in wild-type 5A4 (Fig. 4A). The isolated protein band was analyzed by mass spectrometry and identified to be OspC. Western blot analysis of cell lysates using an anti-OspC antibody confirmed increased levels of OspC in the mutant strain lacking bbd16 to bbd25 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the deleted genes may be involved in the negative regulation of OspC. Less strikingly, Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels also consistently showed a band corresponding to an unknown ∼66-kDa protein with a slightly increased intensity in the mutant strain compared to wild-type 5A4; however, this band was not visualized in the anti-5A4 Western blot.

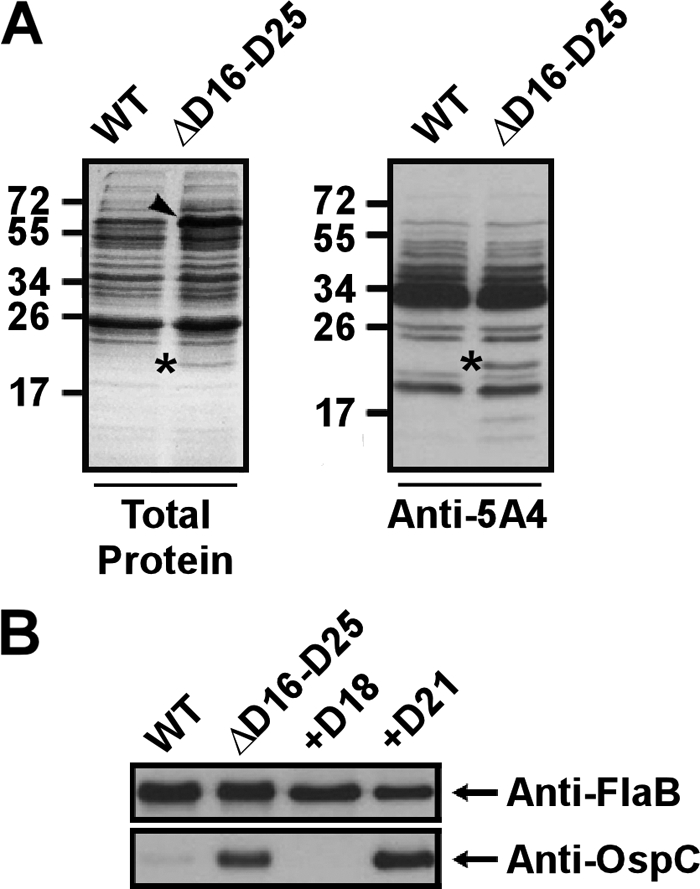

Fig 4.

Increased expression of OspC correlates with the absence of bbd18 in vitro. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel (left) and anti-5A4 Western blot (right) of whole-cell protein preparations from wild-type strain 5A4 (WT) and 5A4ΔD16-D25 (ΔD16-D25), as indicated. The overall protein expression profile was similar for both strains; however, one noticeable additional ∼20-kDa band was visible for the mutant strain, as noted by the asterisks. This band was identified as OspC using LC-MS/MS. Increased intensity of an ∼66-kDa band was also observed for the mutant strain in the Coomassie-stained gel, as indicated by the arrowhead. Numbers to the left of the gels are molecular masses (in kilodaltons). (B) Anti-FlaB (top) and anti-OspC (bottom) Western blots of whole-cell lysates of the wild-type, ΔD16-D25, and 5A4ΔD16-D25 clones complemented with either bbd18 or bbd21 in trans (+D18 and +D21, respectively). Although FlaB levels are comparable for all strains, OspC is detectable only in strains lacking bbd18.

Complementation of 5A4ΔD16-D25 with bbd18 leads to reversal of the mutant OspC expression profile in vitro.

A schematic representation of the 10 predicted ORFs deleted in 5A4ΔD16-D25 is shown in Fig. 1. Of these ORFs, six are extremely small and are predicted to code for proteins of between 3 kDa and 10 kDa. Of the four remaining ORFs, bbd20 and bbd23 have been reported to contain authentic frameshift mutations, while bbd18 and bbd21 are predicted to encode full-length proteins of ∼24 kDa and ∼27 kDa, respectively (21). The protein product coded for by bbd21 belongs to paralogous family 32 (PF32), a family of genes with sequence homology to genes involved in plasmid DNA partitioning, and previous studies have provided some evidence for this function (5, 17). Given the information presented above, bbd18 was an attractive candidate for a single-gene complementation of 5A4ΔD16-D25.

The entire bbd18 gene along with its putative native promoter element was cloned into the self-replicating B. burgdorferi shuttle vector, pBSV2G, which confers gentamicin resistance (19). Although the complemented strain would possess both kanamycin and gentamicin resistance genes (from the original deletion construct and complementing plasmid, respectively), attempts at recovering transformants under both kanamycin and gentamicin selection were unsuccessful. Interestingly, transformants were successfully recovered under gentamicin selection alone. Indeed, although the complemented strain was fully resistant to gentamicin, all recovered clones remained kanamycin sensitive. PCR and Southern blot analysis for both the kanamycin resistance gene and the left end of lp17 showed that all bbd18-complemented clones had lost the truncated version of lp17 (data not shown). Unfortunately, all complemented clones had also lost lp25 containing the virulence-determinant gene bbe22, rendering them unusable for mouse infection studies. The remaining plasmid profile varied between recovered bbd18-complemented clones. An equivalent strategy was utilized to complement the mutant strain with bbd21, including its native promoter. Similar to the bbd18-complemented clones, the majority of bbd21-complemented transformants had lost the original lp17 deletion construct (data not shown).

As deletion of bbd16 to bbd25 resulted in the upregulation of OspC in vitro, the mutant strain complemented with either bbd18 or bbd21 was examined for levels of OspC expression. Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates using an anti-OspC antibody showed that complementation with bbd18 restored OspC expression to below detectable levels (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the bbd18-complemented strain showed a level of OspC expression below that of wild-type 5A4, as seen in Western blots using increased amounts of protein sample or by overexposing the chemiluminescence film during detection (data not shown). Conversely, complementation with bbd21 did not affect OspC levels compared to those of 5A4ΔD16-D25, indicating that the rescued phenotype seen for bbd18 is not an artifact of the complementing plasmid backbone or a general effect of restoring any of the 10 deleted ORFs in 5A4ΔD16-D25 (Fig. 4B). Although it is not known whether OspC expression is influenced by the remainder of the deleted portion of lp17, these results demonstrate that bbd18 is sufficient for the negative regulation of OspC in vitro.

DISCUSSION

B. burgdorferi lp17-borne genes are necessary for efficient tissue colonization.

This study reports the first genetic manipulation of lp17 in a fully infectious strain of B. burgdorferi and the resulting phenotypes both in vitro and in vivo. A mutant B. burgdorferi strain lacking ORFs bbd16 to bbd25 showed no reduction in the ability to establish initial infection and disseminate to the bloodstream in immunocompetent or SCID mice, despite a detectable growth deficiency in vitro. Once initial infection was established, however, this mutant strain was delayed in its ability to colonize tissues regardless of the presence of a fully formed adaptive immune response. It is possible that the delayed ability to reach detectable bacterial levels in vivo might be linked to the observed in vitro growth deficiencies. Alternatively, a 10-fold increase in inoculum had no effect on the ability to recover mutant spirochetes from murine tissues at weeks 1 and 2 postinfection, perhaps suggesting that the observed delay is not due solely to growth defects. The mutant could be recovered from all tissues except bladder tissue during persistent infection of immunocompetent mice, regardless of the infectious dose. This bladder tissue colonization phenotype was not observed in SCID mice, suggesting that it was dependent on the presence of an adaptive immune response. Finally, the B. burgdorferi mutant lacking bbd16 to bbd25 showed increased in vitro expression of OspC, and complementation studies showed that the presence of bbd18 is sufficient for the negative regulation of OspC protein expression in this mutant strain.

Genetic elements on the left end of lp17 are important for viability in fully infectious B. burgdorferi.

The ability to delete large portions of lp17, including all predicted ORFs upstream or downstream of the putative replication initiator bbd14, has been previously demonstrated in the noninfectious isolate B31-A (5). Additionally, individual clones of serially passaged B. burgdorferi strain B31 that have reportedly lost lp17 altogether in conjunction with other plasmids have been isolated (24, 41, 50). Collectively, these studies provide evidence that lp17 is not essential for B. burgdorferi survival in vitro. Successful deletion of bbd16 to bbd25 in 5A4 as reported here is consistent with the notion that lp17 is dispensable in culture.

Conversely, several attempts at deleting ORFs bbd01 to bbd11 in 5A4 were unsuccessful, despite using a similar strategy as previously reported (5). To ensure a proper experimental design, deletion of bbd01 to bbd11 was attempted in B31-A, with success. The reason for the discrepancy between the ability to generate the knockout in B31-A and 5A4 is not known. One possibility is the much higher transformation efficiency in B31-A than 5A4. This explanation is unlikely, however, as the ability to consistently generate other targeted deletions on lp17 would suggest that the transformation efficiency of 5A4 is sufficient. Another possible explanation is that the left-end target region from coordinates 7621 to 8982 is specifically not amenable to genetic manipulations. However, the ability to target the identical region on lp17 in clone B31-A suggests that there is nothing inherent to the left-end target sequence that would resist genetic manipulation. A final possibility is that other unknown differences between B31-A and 5A4 may dictate the ability to delete genes upstream of bbd14. Interplay between genes located on lp17 and other plasmids in 5A4 may not easily permit the loss of some regions of lp17 in the presence of the full complement of 5A4 plasmids. As B31-A lacks at least 9 plasmids found in 5A4, such restrictions may not exist. As the collection of laboratory strains used to study B. burgdorferi is heterogeneous in terms of plasmid content, these results illustrate the importance of considering strain background when interpreting results.

B. burgdorferi lp17-borne genes are important for bladder colonization via adaptive immune avoidance.

The urinary bladder has been well documented to be a consistent source of B. burgdorferi in both experimentally infected and naturally exposed rodents (16, 22, 45, 54). Thus, the finding that B. burgdorferi lacking bbd16 to bbd25 could be detected from all peripheral tissues except the bladder is surprising. The most logical explanation for this observation is a change in the surface protein profile of the mutant strain resulting in altered immunological pressures or receptor-ligand interactions not conducive to bladder colonization. Of these possibilities, an altered profile of surface immunogens in the mutant strain seems most likely, as 5A4ΔD16-D25 was capable of bladder colonization in SCID mice. Liang et al. previously demonstrated that peripheral tissues provide a protective niche from an adaptive anti-B. burgdorferi response and that the bladder and heart tissue provided a lower level of protection than joint and skin tissue (34). As 5A4ΔD16-D25 demonstrated altered OspC expression levels in vitro, aberrant regulation of this or other immunogens may lead to a selective and more pronounced reduction of mutant spirochetes in bladder tissues over tissues at other sites. Liang et al. also demonstrated that while anti-OspC antibodies reduce the proportion of OspC-producing spirochetes in heart, skin, and joint tissues, these antibodies effectively reduce spirochete burdens only in the heart (35, 37). The same group reported unpublished observations that a similar phenotype is observed in bladder tissues, leading to the hypothesis that the relatively low spirochete burden in the bladder compared to the skin and joints of immunocompetent mice is most likely due to a strong anti-OspC immune response (34). Further experiments are needed to determine whether the reduced ability of 5A4ΔD16-D25 to colonize bladder tissues is related to the increased in vitro expression of OspC or other immunogens and to determine whether longer-term infections will result in immune clearance in other mouse tissues.

Although a role for an immune-based mechanism for the defective bladder tissue colonization observed for 5A4ΔD16-D25 is more compelling, altered tissue-specific adhesin/receptor-ligand interactions cannot be ruled out. Several B. burgdorferi outer membrane proteins that bind to host factors, presumably facilitating tissue invasiveness and colonization, in addition to immune evasion, have been described (2, 6, 14, 15, 20, 25–27, 46). It is possible that one of the protein products of bbd16 to bbd25 acts as a tissue-specific adhesin/receptor whose deletion results in altered bladder colonization by the mutant strain.

An important step in characterizing the mechanisms of altered bladder colonization described above will be identification of the individual lp17-borne gene(s) involved. Unfortunately, attempts at single-gene complementation in this study repeatedly resulted in the loss of the original lp17 deletion construct in conjunction with other plasmids, including lp25, resulting in noninfectious clones or those lacking numerous genes that could confound infection results. Thus, future single-gene mutational analysis will provide a more appropriate method for further investigation of this phenotype.

The lp17-resident bbd18 gene is involved in OspC regulation in vitro.

The surface-exposed immunogen OspC must be downregulated upon establishment of initial mammalian infection to avoid clearance by a robust adaptive immune response (35–37, 62). However, the negative regulator(s) involved in this downregulation of OspC has remained elusive. A previous study examined the in vitro expression of OspC in high-passage-number B. burgdorferi B31 clones lacking several linear plasmids (50). Increased expression of OspC correlated with the absence of lp17, suggesting the possible presence of a negative regulator on this plasmid. During the course of the present study, Sarkar et al. confirmed this hypothesis by introducing portions of lp17 into one such clone, B312, which lacks all B31 plasmids except cp26, lp54, and several cp32 plasmids (52). It was found that fragments containing bbd18 were sufficient for reducing in vitro expression of OspC mRNA and protein to wild-type levels in this clone, leading to the suggestion that bbd18 may be acting to suppress OspC production. Because this study involved a clone that lacked the majority of B. burgdorferi B31 plasmids, the question as to whether the absence of bbd18 would have the same effect on OspC expression in an infectious clone with the full complement of parent plasmids remained. The data reported here strongly support this, as the in vitro expression of OspC in B31 lacking only ORFs bbd16 to bbd25 correlated with the presence of bbd18 but not bbd21. It cannot be ruled out, however, that the influence of bbd18 on the expression of OspC may differ in the presence of the nine other deleted ORFs of lp17. Further studies using a bbd18 single-gene knockout are needed to distinguish these possibilities.

Given these new in vitro reports suggesting the ability of bbd18 to directly or indirectly suppress OspC production, it is tempting to speculate that this is the mechanism of OspC downregulation during persistent mammalian infection. If this is the case, the ability of 5A4ΔD16-D25 to persist in mice for 56 days postinfection is somewhat surprising. A previous study reported that spirochetes constitutively expressing ospC could be consistently recovered from mice during the first 8 weeks of infection and were cleared only by 11 weeks postinfection (62). A second study using a different genetic model system reported clearance of constitutively ospC-expressing spirochetes by 3 weeks postinfection (61). It is not currently known how the loss of bbd18 affects ospC expression during persistent infection or how the infection results reported here for 5A4ΔD16-D25 relate to previous studies of B. burgdorferi strains unable to downregulate ospC.

A recent study by Xu et al. demonstrated that transcription of ospC is regulated during persistent infection via the presence of a large cis-acting operator region consisting primarily of two inverted repeat DNA sequences located immediately upstream of the ospC promoter (61). Such cis-acting elements can act as sites for the binding of specific transcriptional repressor proteins. Interestingly, it was found that although deletion of the ospC operator region abolished the ability of B. burgdorferi to downregulate ospC during persistent infection, this palindromic sequence is not involved in regulation of ospC expression in vitro (61). Thus, deletion of bbd18 appears to have a different in vitro effect on ospC expression than deletion of the ospC operator region. It is possible that the bbd18-dependent downregulation of ospC in vitro reported here and by Sarkar et al. (52) occurs through a yet unidentified mechanism different from that reported by Xu et al. during mammalian infection (61). Further studies investigating the expression pattern and mode of action of bbd18 will likely identify the stage at which bbd18 regulates ospC during the B. burgdorferi infectious cycle.

Despite numerous previous studies investigating the involvement of plasmid-borne genes during the infectious cycle of B. burgdorferi, the role of lp17-borne genes during mammalian infection has remained unknown. This study has demonstrated for the first time the effects of lp17 gene deletion on murine infection by B. burgdorferi. Although the relevance of the observed phenotypes to B. burgdorferi pathogenesis is not yet known, future studies investigating the mechanism of impaired bladder colonization in the mutant strain will allow a better understanding of the mechanisms of B. burgdorferi persistence during mammalian infection. Furthermore, the targeted deletion strategy described herein is being used in conjunction with more traditional gene deletion methods to further define the role of other lp17 genes during mammalian infection. This highly conserved yet relatively uncharacterized plasmid has now been shown to encode at least one regulator of a known mammalian virulence determinant, in addition to being required for efficient colonization of murine tissues. Thus, lp17 remains an attractive target for future studies involving the Lyme disease spirochete.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank George Chaconas for the strains used in this study.

This work was supported by an intramural grant from the College of Veterinary Medicine at Washington State University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 February 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Angel TE, et al. 2010. Proteome analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi response to environmental change. PLoS One 5:e13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antonara S, Chafel RM, LaFrance M, Coburn J. 2007. Borrelia burgdorferi adhesins identified using in vivo phage display. Mol. Microbiol. 66:262–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bankhead T, Chaconas G. 2007. The role of VlsE antigenic variation in the Lyme disease spirochete: persistence through a mechanism that differs from other pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1547–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barbour AG. 1984. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol. Med. 57:521–525 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beaurepaire C, Chaconas G. 2005. Mapping of essential replication functions of the linear plasmid lp17 of B. burgdorferi by targeted deletion walking. Mol. Microbiol. 57:132–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Behera AK, et al. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi BBB07 interaction with integrin alpha3beta1 stimulates production of pro-inflammatory mediators in primary human chondrocytes. Cell. Microbiol. 10:320–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boardman BK, et al. 2008. Essential role of the response regulator Rrp2 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 76:3844–3853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bono JL, et al. 2000. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 182:2445–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brooks CS, Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Akins DR. 2003. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71:3371–3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burgdorfer W, et al. 1982. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 216:1317–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Caimano MJ, et al. 2007. Analysis of the RpoS regulon in Borrelia burgdorferi in response to mammalian host signals provides insight into RpoS function during the enzootic cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1193–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Casjens S, et al. 2000. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 35:490–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaconas G, Stewart PE, Tilly K, Bono JL, Rosa P. 2001. Telomere resolution in the Lyme disease spirochete. EMBO J. 20:3229–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coburn J, Chege W, Magoun L, Bodary SC, Leong JM. 1999. Characterization of a candidate Borrelia burgdorferi beta3-chain integrin ligand identified using a phage display library. Mol. Microbiol. 34:926–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coburn J, Magoun L, Bodary S, Leong JM. 1998. Integrins avb3 and a5b1 mediate attachment of Lyme disease spirochetes to human cells. Infect. Immun. 66:1946–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Czub S, Duray PH, Thomas RE, Schwan TG. 1992. Cystitis induced by infection with the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 141:1173–1179 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deneke J, Chaconas G. 2008. Purification and properties of the plasmid maintenance proteins from the Borrelia burgdorferi linear plasmid lp17. J. Bacteriol. 190:3992–4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dulebohn DP, Bestor A, Rego RO, Stewart PE, Rosa PA. 2011. Borrelia burgdorferi linear plasmid 38 is dispensable for completion of the mouse-tick infectious cycle. Infect. Immun. 79:3510–3517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elias AF, et al. 2003. New antibiotic resistance cassettes suitable for genetic studies in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6:29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fischer JR, LeBlanc KT, Leong JM. 2006. Fibronectin binding protein BBK32 of the Lyme disease spirochete promotes bacterial attachment to glycosaminoglycans. Infect. Immun. 74:435–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fraser CM, et al. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodman JL, Jurkovich P, Kodner C, Johnson RC. 1991. Persistent cardiac and urinary tract infections with Borrelia burgdorferi in experimentally infected Syrian hamsters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:894–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grimm D, et al. 2004. Experimental assessment of the roles of linear plasmids lp25 and lp28-1 of Borrelia burgdorferi throughout the infectious cycle. Infect. Immun. 72:5938–5946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grimm D, Elias AF, Tilly K, Rosa PA. 2003. Plasmid stability during in vitro propagation of Borrelia burgdorferi assessed at a clonal level. Infect. Immun. 71:3138–3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guo BP, Brown EL, Dorward DW, Rosenberg LC, Hook M. 1998. Decorin-binding adhesins from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 30:711–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hagman KE, et al. 1998. Decorin-binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi is encoded within a two-gene operon and is protective in the murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 66:2674–2683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hu LT, et al. 1997. Isolation, cloning, and expression of a 70-kilodalton plasminogen binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 65:4989–4995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jewett MW, et al. 2007. The critical role of the linear plasmid lp36 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1358–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kawabata H, Norris SJ, Watanabe H. 2004. BBE02 disruption mutants of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 have a highly transformable, infectious phenotype. Infect. Immun. 72:7147–7154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kobryn K, Chaconas G. 2002. ResT, a telomere resolvase encoded by the Lyme disease spirochete. Mol. Cell 9:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Labandeira-Rey M, Seshu J, Skare JT. 2003. The absence of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1 of Borrelia burgdorferi dramatically alters the kinetics of experimental infection via distinct mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 71:4608–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Labandeira-Rey M, Skare JT. 2001. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect. Immun. 69:446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lane RS, Piesman J, Burgdorfer W. 1991. Lyme borreliosis: relation of its causative agent to its vectors and hosts in North America and Europe. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 36:587–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liang FT, Brown EL, Wang T, Iozzo RV, Fikrig E. 2004. Protective niche for Borrelia burgdorferi to evade humoral immunity. Am. J. Pathol. 165:977–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liang FT, Jacobs MB, Bowers LC, Philipp MT. 2002. An immune evasion mechanism for spirochetal persistence in Lyme borreliosis. J. Exp. Med. 195:415–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liang FT, Nelson FK, Fikrig E. 2002. Molecular adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine host. J. Exp. Med. 196:275–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liang FT, et al. 2004. Borrelia burgdorferi changes its surface antigenic expression in response to host immune responses. Infect. Immun. 72:5759–5767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Livengood JA, Schmit VL, Gilmore RD., Jr 2008. Global transcriptome analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi during association with human neuroglial cells. Infect. Immun. 76:298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller JC, et al. 2000. A second allele of eppA in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is located on the previously undetected circular plasmid cp9-2. J. Bacteriol. 182:6254–6258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Norris SJ, Howell JK, Garza SA, Ferdows MS, Barbour AG. 1995. High- and low-infectivity phenotypes of clonal populations of in vitro-cultured Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 63:2206–2212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Norris SJ, et al. 2011. High-throughput plasmid content analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 by using Luminex multiplex technology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1483–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ojaimi C, et al. 2003. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71:1689–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ouyang Z, Blevins JS, Norgard MV. 2008. Transcriptional interplay among the regulators Rrp2, RpoN and RpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 154:2641–2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ouyang Z, et al. 2009. BosR (BB0647) governs virulence expression in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1331–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petney TN, Hassler D, Bruckner M, Maiwald M. 1996. Comparison of urinary bladder and ear biopsy samples for determining prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in rodents in central Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1310–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Probert WS, Johnson BJ. 1998. Identification of a 47 kDa fibronectin-binding protein expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi isolate B31. Mol. Microbiol. 30:1003–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Purser JE, et al. 2003. A plasmid-encoded nicotinamidase (PncA) is essential for infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in a mammalian host. Mol. Microbiol. 48:753–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Purser JE, Norris SJ. 2000. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13865–13870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rogers EA, et al. 2009. Rrp1, a cyclic-di-GMP-producing response regulator, is an important regulator of Borrelia burgdorferi core cellular functions. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1551–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sadziene A, Wilske B, Ferdows MS, Barbour AG. 1993. The cryptic ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 is located on a circular plasmid. Infect. Immun. 61:2192–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Samuels DS. 1995. Electrotransformation of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:253–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sarkar A, Hayes BM, Dulebohn DP, Rosa PA. 2011. Regulation of the virulence determinant OspC by bbd18 on linear plasmid lp17 of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 193:5365–5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schwan TG, Burgdorfer W, Garon CF. 1988. Changes in infectivity and plasmid profile of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as a result of in vitro cultivation. Infect. Immun. 56:1831–1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schwan TG, Burgdorfer W, Schrumpf ME, Karstens RH. 1988. The urinary bladder, a consistent source of Borrelia burgdorferi in experimentally infected white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus). J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:893–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1093–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stevenson B, et al. 1997. Characterization of cp18, a naturally truncated member of the cp32 family of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 179:4285–4291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Strother KO, de Silva A. 2005. Role of Borrelia burgdorferi linear plasmid 25 in infection of Ixodes scapularis ticks. J. Bacteriol. 187:5776–5781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tokarz R, Anderton JM, Katona LI, Benach JL. 2004. Combined effects of blood and temperature shift on Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression as determined by whole genome DNA array. Infect. Immun. 72:5419–5432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tourand Y, et al. 2006. Differential telomere processing by Borrelia telomere resolvases in vitro but not in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 188:7378–7386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tourand Y, Kobryn K, Chaconas G. 2003. Sequence-specific recognition but position-dependent cleavage of two distinct telomeres by the Borrelia burgdorferi telomere resolvase, ResT. Mol. Microbiol. 48:901–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xu Q, McShan K, Liang FT. 2007. Identification of an ospC operator critical for immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 64:220–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu Q, Seemanapalli SV, McShan K, Liang FT. 2006. Constitutive expression of outer surface protein C diminishes the ability of Borrelia burgdorferi to evade specific humoral immunity. Infect. Immun. 74:5177–5184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xu Y, Kodner C, Coleman L, Johnson RC. 1996. Correlation of plasmids with infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto type strain B31. Infect. Immun. 64:3870–3876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]