Abstract

“Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis” is a robust and pervasive environmental bacterium that can cause opportunistic infections in humans. The bacterium overcomes the host immune response and is capable of surviving and replicating within host macrophages. Little is known about the bacterial mechanisms that facilitate these processes, but it can be expected that surface-exposed proteins play an important role. In this study, the selective biotinylation of surface-exposed proteins, streptavidin affinity purification, and shotgun mass spectrometry were used to characterize the surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis. This analysis detected more than 100 proteins exposed at the bacterial surface of M. avium subsp. hominissuis. Comparisons of surface-exposed proteins between conditions simulating early infection identified several groups of proteins whose presence on the bacterial surface was either constitutive or appeared to be unique to specific culture conditions. This proteomic profile facilitates an improved understanding of M. avium subsp. hominissuis and how it establishes infection. Additionally, surface-exposed proteins are excellent targets for the host adaptive immune system, and their identification can inform the development of novel treatments, diagnostic tools, and vaccines for mycobacterial disease.

INTRODUCTION

The characterization of the surface-exposed proteome of a cell provides key insights into its nature. Surface-exposed proteins play a fundamental role in both how a cell interacts with its environment and how it is perceived by other cells. For infectious bacteria, surface proteins are essential components of many aspects of pathogenesis (47, 48). Host specificity, adhesion, invasion, molecular transport, and antimicrobial resistance are processes known to be directly mediated by proteins present at the surface interface (16, 17, 50, 81). These proteins are also the primary target of the host immune system. Effective cellular and humoral immune responses depend on targeting accessible molecules, which tend to be on the surface of a pathogen (87). With respect to mycobacteria, putative and known surface-exposed proteins comprise a substantial proportion of antigens observed in comprehensive screens using sera from mycobacterium-infected hosts (37, 42, 45, 85). The characterization of these proteins improves our understanding of bacterial pathogenesis and host immunity, providing insights that can lead to new diagnostic tools and vaccines (38, 87).

“Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis” is a common environmental pathogen and a major source of disseminated mycobacterial disease in immune-compromised individuals (11). It is closely related to another pathogenic member of the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. M. avium subsp. hominissuis also shares many genetic and structural features with its more virulent relatives, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium marinum. Capable of surviving within a hijacked phagosome, M. avium subsp. hominissuis replicates within host macrophages (15). Like other pathogenic mycobacteria, M. avium subsp. hominissuis interferes with the typical process of vacuole maturation and establishes a stable niche. It is likely that, along with fully secreted molecules, proteins expressed on the bacterial surface play a role in the intracellular processes associated with survival and persistence. Despite residing within a vacuole for the majority of the intracellular phase of infection, very little is known about the interaction between M. avium subsp. hominissuis and the host phagosome. Possible interference with the activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs), inactivation of host antimicrobial responses, and modulation of molecular transport into and out of the vacuole are all functions that may be mediated by surface proteins (19).

In this study, we employed an emerging technological approach to characterize the surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis that was cultured under conditions simulating early infection. The combination of the selective biotinylation of surface-exposed proteins, affinity purification, and so-called shotgun mass spectrometry is a powerful tool that can generate a snapshot of the surface proteome of a cell (20, 49, 70). While this general approach has been applied to a range of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells, including several species of pathogenic bacteria (33, 73, 82), it has not been used to characterize the surface proteome in mycobacteria. In this report, we harness the technology to analyze the surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis, focusing on the earliest stages of macrophage infection. Combining all experimental conditions, our results identified more than 100 proteins from the surface of M. avium subsp. hominissuis. Within this total population, our analysis identified a set of core proteins that appeared to be constitutively abundant on the bacterial surface, as well as several sets of proteins whose surface exposure appears to be dependent on the experimental condition. The comparison of these results with previously reported surface-exposed proteome data from other mycobacterial species revealed that the majority of the proteins identified in this study have homologs across the genus that are known to be secreted, surface-exposed, or cell-wall-associated proteins. Furthermore, the proteins identified in this screen are disproportionately represented among the population of proteins that have previously been identified as dominant antigens in mycobacterial infection. This characterization of the M. avium subsp. hominissuis surface-exposed proteome builds upon previous reports and significantly expands our understanding of the proteins that mediate the earliest stages of M. avium subsp. hominissuis pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of macrophage and M. avium subsp. hominissuis cultures.

RAW 264.7 cells (a mouse macrophage cell line) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Adherent RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, in 300-cm2 glass trays, to a confluence of ∼50%. Prior to the start of the experiment, M. avium subsp. hominissuis strain 109 (a clinical isolate from the blood of an HIV/AIDS patient) was cultured in 200 ml of Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco, Sparks, MD) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria CA) broth at 37°C for 4 days with constant agitation, until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was approximately 1. To initiate the experiment, bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g and washed twice with Hank's buffered salt solution (HBSS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Bacteria were resuspended in 40 ml of HBSS and separated into eight equal (50-ml) aliquots.

Experimental culture conditions.

For medium-only experimental conditions (Middlebrook 7H9 broth and DMEM), the 5-ml aliquot was added to 30 ml fresh medium in a 50-ml tube and placed in an incubator at 37°C with gentle shaking. For macrophage-exposed bacteria, each aliquot of washed bacteria was split among four trays of macrophages for a final multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼10. Samples were harvested at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Extracellular bacteria (ECB) were isolated from infected macrophage cultures first. For the purposes of this study, ECB are defined as M. avium subsp. hominissuis incubated with macrophage cells but not phagocytosed. To isolate ECB, infected macrophage cultures were washed with HBSS three times to remove any bacteria that were not inside adherent cells. This wash solution was combined and centrifuged (1,500 × g for 10 min) to pellet the bacteria and any nonadherent macrophage cells. Nonadherent macrophages were then pelleted by low-speed centrifugation (100 × g for 2 min). Very few nonadherent macrophage cells were observed in intracellular M. avium subsp. hominissuis bacteria (ICB) samples from either time point. ICB samples then were isolated from infected macrophages. For the purpose of this study, ICB were defined as M. avium subsp. hominissuis cells that were incubated with and phagocytosed by the cultured macrophages. To isolate ICB, the infected macrophages were incubated for 5 min in cold differential lysis buffer (DLB; 90% H2O, 9.8% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20). This buffer disrupts the membranes of RAW 264.7 cells but not those of the M. avium subsp. hominissuis, which are shielded by the robust mycobacterial cell envelope. The cells were scraped, completely removing all material, and combined into 50-ml centrifuge tubes. The samples were shaken and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 15 min. This centrifugation collected both the bacteria and significant cell debris. The pellet was resuspended in 5 ml and transferred to clean tubes. Bacteria were isolated from cell debris by differential centrifugation in DLB. First, the majority of large cell debris was pelleted by low-speed centrifugation (100 × g for 2 min). Supernatant (containing bacteria in suspension) was transferred to clean tubes. This sequence of low- and high-speed centrifugation was repeated an additional two times. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation (4,000 × g for 5 min), and supernatant was discarded. Bacteria then were washed twice with BupH-PBS (150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.3) prior to biotin labeling. Samples from medium-only culture conditions were collected by centrifugation and washed in the same fashion.

Biotin labeling and purification of M. avium subsp. hominissuis surface proteins.

Bacterial pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of BupH-PBS. To biotinylated surface-exposed proteins, 500 μl of Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was added at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in BupH-PBS to each sample. Bacteria were biotin labeled for 20 min at 23°C with gentle agitation. After labeling, bacteria were washed twice with BupH-PBS supplemented with glycine (10 mg/ml) and two times with plain BupH-PBS to inactivate and remove any unbound Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin. Labeled bacteria were resuspended in urea lysis buffer (ULB; 140 mM NaCl, 20 mM Na2HPO4, 7 M urea, 0.05% [vol/vol] Tween 20, 0.1% [wt/vol] deoxycholic acid, pH 7.2) and disrupted by bead milling with 100-μm glass beads (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After disruption, samples were centrifuged (12,000 × g for 10 min) to remove particulates and other insoluble components, and the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube to be used for purification. Prior to affinity capture, samples were diluted 1:3 with WB-PBS (140 mM NaCl, 20 mM Na2HPO4, 0.05% [vol/vol] Tween 20, pH 7.2). Samples in this adjusted buffer, termed urea incubation buffer (UIB; 140 mM NaCl, 20 mM Na2HPO4, 1.75 M urea, 0.05% [vol/vol] Tween 20, 0.025% [wt/vol] deoxycholic acid, pH 7.2), were used for streptavidin affinity purification. Biotinylated protein was purified from total protein by affinity purification with magnetic streptavidin-coated C1 Dynabeads (Invitrogen). Briefly, aliquots of 1.5 ml of biotinylated protein solution was incubated for 30 min at 23°C with 80 μl of C1 Dynabeads. Samples were washed three times with 1 ml of UIB, twice with 1 ml WB-PBS, and once with 1 ml of ammonium bicarbonate buffer (ABB) (50 mM NH4HCO3, pH 7.8). Samples were resuspended in 50 μl ABB and digested with trypsin gold (1 μg; protease-to-substrate ratio of ∼1:20) and ProteaseMAX according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI).

Preparation of negative controls.

To eliminate nonspecific background and endogenously biotinylated proteins, samples of M. avium subsp. hominissuis were isolated from the conditions described above for use as negative controls. These samples were processed in the manner described above, except that Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin was not added. Data from negative controls were pooled to create a master list of false-positive identifications, and these proteins were then subtracted from the experimental data sets. The negative-control master list is included in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Peptide purification, proteolysis, and LC-MS/MS analysis.

Following enzymatic proteolysis, magnetic stands were used to remove the beads from the completed digests. Peptides from the resulting supernatant were purified and desalted on Vivapure C18 microspin columns according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany). After purification, peptides were dehydrated by speed vacuum and resuspended to a final concentration of approximately 500 ng/μl in mass spectrometry (MS) loading buffer (95% H2O, 5% [vol/vol] acetonitrile [ACN], 0.1% [vol/vol] formic acid). Data-dependent liquid chromatography-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) analyses were performed on an LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer with an IonMax ion source (Thermo, West Palm Beach, FL) coupled to a nanoAcquity Ultra performance LC system (Waters, Milford, MA) equipped with a Michrom peptide CapTrap column and a C18 column (Zorbax 300SB-C18; 250 by 0.3 mm; 5-μm volume; Agilent). A binary gradient system was used consisting of solvent A (0.1% aqueous formic acid) and solvent B (ACN containing 0.1% [vol/vol] formic acid). Two μl of C18 column-purified peptides was trapped and washed with 3% solvent B at a flow rate of 5 μl/min for 3 min. Trapped peptides were then eluted into an analytical column using a linear gradient from 3% B to 30% B at a flow rate of 4 μl/min for 35 min. The column was maintained at 37°C during the run. The mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent acquisition mode. A full FT-MS scan (m/z 350 to 2,000) was alternated with collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS scans of the 5 most abundant doubly or triply charged precursor ions. As the survey scan was acquired in the ion cyclotron resonance (ICR) cell, the CID experiments were performed in the linear ion trap, where precursor ions were isolated and subjected to CID in parallel with the completion of the full FT-MS scan. CID was performed with helium gas at a normalized collision energy of 35% and an activation time of 30 ms. Automated gain control (AGC) was used to accumulate sufficient precursor ions (target value, 5 × 104/microscan; maximum fill time, 0.2 s). Dynamic exclusion was used with a repeat count of 1 and exclusion duration of 60 s. Data acquisition was controlled by Xcalibur (version 2.0.5) software (Thermo Scientific).

Database search.

Thermo Scientific data files were processed with Proteome Discoverer, version 1.2, using default parameters. A Mascot (version 2.2.04) search against the whole Swiss-Prot 2010 database (523,151 sequences; 184,678,199 residues) or an M. avium subsp. hominissuis (strain 104) database (obtained from UniProt; 5,040 sequences; 1,586,464 residues) was launched from Proteome Discoverer with the following parameters. The digestion enzyme was set to Trypsin/P, and two missed cleavage sites were allowed. The precursor ion mass tolerance was set to 5 ppm, while a fragment ion tolerance of 0.8 Da was used. Dynamic modifications included carbamidomethyl (+57.0214 Da) for Cys, oxidation (+15.9994 Da) for Met, and LC-Biotin (+339). Data from two experimental replicates were combined by MudPIT (multidimensional protein identification technology), and identified proteins from each sample were summarized with Scaffold 3 software (Proteome Software, Portland, OR). The inclusion of a protein in the final data set required that two or more unique peptides for that protein could be identified in at least one experimental condition. Only peptides that were identified with a confidence of greater than 50% were utilized to calculate the overall probability of protein identification.

Sequential fractionation and Western blotting.

To assess the solubility of biotin-labeled proteins, three test samples (one negative-control and two experimental samples [DMEM and 7H9]) were subjected to sequential fractionation. Briefly, samples were prepared, washed, and disrupted as described above. Each extraction was repeated twice. First, BupH-PBS-soluble proteins were extracted, and the remaining material (insoluble in BupH-PBS) was pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min. Pellets were then resuspended in ULB and incubated at 37°C for 10 min, with vigorous agitation. Soluble proteins were again separated by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 20 min), and the supernatant (containing ULB-soluble proteins) was transferred to a clean tube. The remaining pellets were resuspended in Laemmli SDS-PAGE buffer and heated to 95°C for 10 min. Protein concentrations were equilibrated between samples using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Following SDS-PAGE separation, proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes in preparation for Western blot analysis. IRDye-680 streptavidin (Licor, Lincoln, NE) was used to probe membranes by following the manufacturer's protocol. Biotinylation patterns were visualized on an Odyssey scanner (Licor).

Functional classification of identified proteins.

Where a direct homolog between an identified M. avium subsp. hominissuis protein and its counterpart in M. tuberculosis existed, functional annotations were drawn from the Tuberculist database (44). For the purposes of this study, direct homologs were defined as those proteins having greater than 60% identity. Where a direct homolog in M. tuberculosis was absent, annotations were assigned based on BLAST and literature searches. The presence and identification of the direct homologs for the M. avium subsp. hominissuis proteins identified in this study are detailed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

Selective biotinylation of surface-exposed proteins.

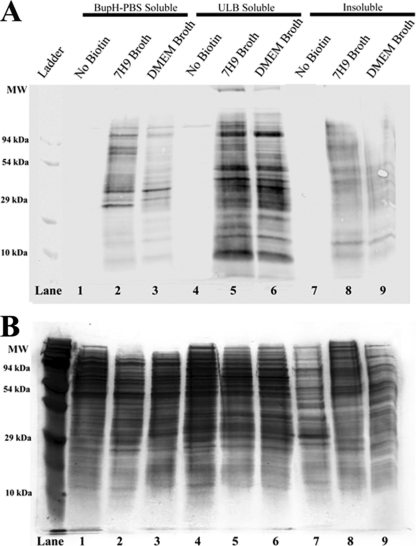

The membrane impermeability and selective labeling of surface proteins with Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin has been demonstrated in a wide range of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (20, 24, 33). Because of the extensive washing required by the methodology used in this study, the detected proteins were expected to be firmly associated with the bacterial cell envelope. To confirm the selective biotinylation of surface-exposed proteins, samples of Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin-labeled M. avium subsp. hominissuis were subjected to sequential fractionation by solubility, and the resulting fractions were analyzed by anti-biotin Western blotting (Fig. 1A). Most cytoplasmic proteins are expected to be soluble in BupH-PBS, while most membrane and cell wall-associated proteins are expected to be solubilized in ULB, which contains detergents and urea. The remaining, insoluble fraction was expected to be enriched in proteins that are highly hydrophobic, posttranslationally modified, tightly complexed with nonsoluble components, or otherwise resistant to solubilization. The results of this sequential fractionation demonstrate that most of the biotin-labeled proteins are indeed solubilized only with the addition of urea and detergent (Fig. 1). In contrast, relatively few proteins in the BupH-PBS and insoluble fractions were labeled with biotin. However, the presence of some biotinylated protein in the remaining insoluble fraction indicates that some surface-exposed proteins were not effectively extracted by the methods used in this study. Overall, the enrichment of biotinylated proteins in the ULB-soluble fraction suggests that the majority of biotin-labeled proteins are hydrophobic proteins that are membrane or cell wall associated, and that cytoplasmic M. avium subsp. hominissuis proteins were not significantly biotinylated.

Fig 1.

Biotin labeling of M. avium subsp. hominissuis proteins separated by solubility. Protein was analyzed from three M. avium subsp. hominissuis samples, one negative control (not biotinylated) and two experimental samples (biotinylated). Protein was isolated on the basis of solubility in three consecutive extractions. The first extraction was performed in BupH-PBS and isolated primarily PBS-soluble proteins that are expected to be soluble in native conditions (lanes 1 to 3). The pellet remaining from the first extraction was resuspended in ULB, which was expected to solubilize most of the membrane and cell envelope-associated proteins (lanes 4 to 6). The pellet remaining after the extraction of ULB-soluble proteins was resuspended in Laemmli buffer and heated to 95°C for 10 min to extract as much of the remaining protein as possible (lanes 7 to 9). (A) Anti-biotin Western blotting indicates that the majority of the biotin-labeled protein was present in the ULB fraction. Some signal was detected in the insoluble fraction, indicating that some surface-exposed proteins were unidentifiable in this study. The negative control shows minimal staining, suggesting low levels of endogenous biotinylation. (B) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE gel of the same protein samples.

Total protein identification.

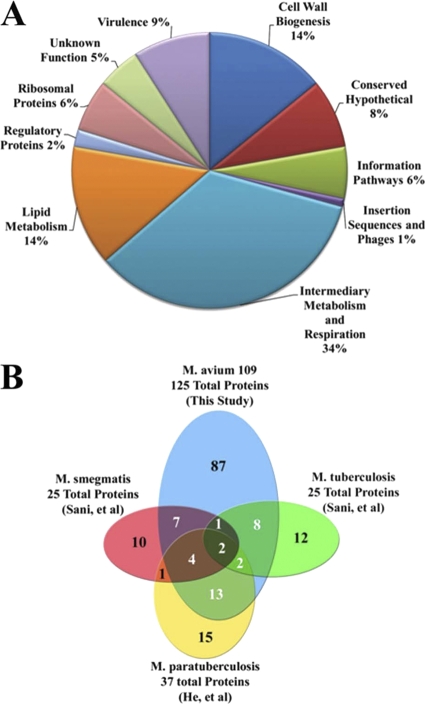

In total, our analysis identified in excess of 100 putative surface-exposed proteins (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The identified proteins were distributed among a variety of functional classifications (Fig. 2A). Many previously described surface-exposed or secreted antigens of mycobacteria were identified in this study, including the antigen 85 complex (ag85A, locus tag MAV_0214; ag85C, MAV_0215; and ag85B, MAV_2816), heparin-binding hemagglutinin (hbha, MAV_4675), and superoxide dismutase (sodA, MAV_0182). The predominant functional group among the proteins detected in this study are categorized by Tuberculist as “Intermediary Metabolism and Respiration,” which accounted for 34% of all identified proteins. As expected, proteins that are predicted to be involved in cell wall biogenesis and maintenance were well represented, comprising 14% of the total. An additional 14% of the total was represented by proteins with putative roles in lipid metabolism, many of which are also expected to have functions associated with the development of the mycobacterial cell envelope. Approximately 9% of the identified proteins are classified by Tuberculist as virulence related. These included multiple proteins that participate in the response to stress and host oxidative responses, such as catalase (katG, MAV_2753), alkylhydroperoxide reductase (ahpC, MAV_2839), and universal stress family proteins (MAV_2506 and MAV_3137). Several proteins with putative nucleotide binding functions, including multiple ribosomal proteins, were also identified. A large number of ribosomal proteins also were detected in negative controls, which indicates that at least some of the observed ribosomal proteins are persistent contaminants (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig 2.

Functional grouping and interstudy cross-referencing of identified surface-exposed proteins. (A) Distribution of functional annotations of identified M. avium subsp. hominissuis surface-exposed proteins. Direct homologues of all M. avium subsp. hominissuis proteins identified in this study were identified for M. tuberculosis, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, M. smegmatis, and M. marinum (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Functional classification for identified M. avium subsp. hominissuis proteins was assigned, where applicable, by using the annotated functional grouping of the M. tuberculosis homolog in the Tuberculist database. (B) Venn diagram illustrating overlap between surface proteins identified in published studies of the surface-exposed proteomes of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, M. smegmatis, and M. tuberculosis and the data presented here for M. avium subsp. hominissuis. The data sets for M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis employed selective solubilization to isolate surface proteins and included only the 25 most abundant surface proteins. The data for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis employed a trypsin-shaving approach and included all confidently identified surface proteins (30–32, 51, 54, 74, 84).

To assess the relevance of these results, the proteins identified in this screen were cross-referenced against the surface-exposed proteins identified in two published analyses of related mycobacterial species (32, 74). Unlike the selective labeling and affinity purification method employed here, the previous work employed either trypsin shaving or cell envelope solubilization to selectively isolate and identify proteins and peptides from the surface of several species of Mycobacterium, including M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, M. smegmatis, and M. tuberculosis. The comparison between the findings of the three studies reveals considerable overlap between the previously identified mycobacterial proteins and the M. avium subsp. hominissuis surface-exposed proteins observed in this study (Fig. 2B; also see Table 4). Approximately 57% (21/37) of the surface-exposed proteins identified in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis were also detected in this study (32). Similar results were observed for M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis, 52% (13/25) and 56% (14/25), respectively (74). Interestingly, while there was a high degree of similarity between this study and the previous studies, there was substantially less overlap between these studies themselves (Fig. 2B). This discrepancy, which is explored more thoroughly in the discussion, likely stems from critical differences between the methods used to isolate proteins for analysis. Beyond the comparisons visualized in Fig. 2, if the scope of reference is expanded to include proteins identified in published studies that comprehensively profile membrane, cell wall, and secreted proteins of M. marinum, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, and M. tuberculosis, the results indicate that ∼90% of the proteins detected in this study are close homologues of proteins previously identified as plasma membrane, secreted, and/or cell wall-associated mycobacterial proteins (30, 32, 51, 54, 84, 87) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Table 4.

Cross-referenced list of proteins identified in studies profiling the surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis 109, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, M. tuberculosis, and M. smegmatisa

| Uniprot annotation | Protein identification |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. avium subsp. hominissuis 109 (this study) | M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (32) | M. tuberculosis (74) | M. smegmatis (74) | |

| 60-kDa chaperonin 2 | MAV_4707 | MAP3936 | Rv3417c | MSMEG_0880 |

| Chaperone protein dnaK | MAV_4808 | MAP3840 | Rv0350 | MSMEG_0709 |

| Elongation factor Tu | MAV_4489 | MAP4143 | NA | MSMEG_1401 |

| Acyl carrier protein | MAV_2913 | MAP1997 | Rv2244 | NA |

| Heparin-binding hemagglutinin | MAV_4675 | MAP3968 | NA | NA |

| Alkylhydroperoxide reductase C | MAV_2839 | MAP1589c | NA | MSMEG_4891 |

| Adenosylhomocysteinase | MAV_4211 | MAP3362c | NA | NA |

| 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase 1 | MAV_2192 | MAP1998 | NA | NA |

| 10-kDa chaperonin | MAV_4366 | MAP4264 | NA | NA |

| FadA2 | MAV_4915 | MAP3693 | NA | NA |

| Transcriptional regulator, Crp/Fnr family protein | MAV_0453 | MAP0398c | NA | NA |

| Succinyl-coenzyme A ligase | MAV_1074 | MAP0896 | NA | NA |

| Uncharacterized oxidoreductase | MAV_3816 | MAP3007 | NA | NA |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | MAV_3341 | MAP1164 | NA | MSMEG_3084 |

| Wag31 | MAV_2345 | MAP1889c | NA | NA |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha | MAV_4398 | MAP4233 | NA | NA |

| Electron transfer protein, beta subunit | MAV_3876 | MAP3061c | NA | MSMEG_2351 |

| Unknown protein | MAV_3813 | MAP3005c | NA | NA |

| Peroxisomal multifunctional enzyme | MAV_5146 | MAP3567 | NA | NA |

| ATP synthase alpha chain | MAV_1525 | MAP2453c | Rv1308 | NA |

| ATP synthase beta chain | MAV_1527 | NA | Rv1310 | NA |

| ATP synthase gamma chain | MAV_1526 | NA | Rv1309 | NA |

| ATP synthase delta chain | MAV_1524 | NA | Rv1307 | NA |

| Aconitate hydratase 1 | MAV_3303 | NA | Rv1475c | MSMEG_3143 |

| Unknown protein | MAV_3615 | NA | Rv2721c | NA |

| MetE | MAV_1262 | NA | Rv1133c | NA |

| Oxidoreductase | MAV_4916 | NA | Rv0242c | NA |

| Catalase-peroxidase | MAV_2753 | NA | Rv1908c | NA |

| Glutamine synthase | MAV_2267 | NA | NA | MSMEG_4290 |

| Succinyl-CoA ligase | MAV_1075 | NA | NA | MSMEG_5524 |

| Universal stress protein | MAV_3137 | NA | NA | MSMEG_3811 |

| Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | MAV_3850 | NA | NA | MSMEG_2374 |

| 60 kDa chaperonin 1 | MAV_4365 | NA | NA | MSMEG_1583 |

| Ribosomal protein S8 | MAV_4451 | NA | NA | MSMEG_1469 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 | MAV_4507 | NA | NA | MSMEG_1365 |

| Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_2412 | NA | Rv2091c | NA |

| MihF protein | Negative control | MAP1122 | NA | MSMEG_3050 |

| DNA binding protein HU | Negative control | MAP3024c | NA | NA |

| 30S Ribosomal protein 3 | Negative control | MAP4167 | NA | NA |

| Malate synthase G | Negative control | NA | Rv1837c | NA |

| Ribosomal protein L18 | Negative control | NA | NA | MSMEG_1471 |

| Enolase | NA | MAP0990 | NA | NA |

| FadE3 | NA | MAP3651c | NA | NA |

| PPE protein PPE26 | NA | MAP1506 | NA | NA |

| PPE protein PPE30 | NA | MAP1519 | NA | NA |

| DesA2 | NA | MAP2698c | NA | NA |

| Unknown protein | NA | MAP1563c | NA | NA |

| PPE protein PPE61 | NA | MAP3532 | NA | NA |

| SerA | NA | MAP3033c | NA | NA |

| FadE24 | NA | MAP3188 | NA | NA |

| Alkylhydroperoxide reductase D | NA | MAP1588c | NA | NA |

| FadE18 | NA | MAP2228 | NA | NA |

| ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit | NA | MAP2280c | NA | NA |

| WXG100 protein EsxP | NA | MAP1508 | NA | NA |

| Proline-rich protein | NA | NA | Rv1078 | NA |

| Conserved membrane protein | NA | NA | Rv0227c | NA |

| Serine protease HtrA | NA | NA | Rv1223 | NA |

| Unknown protein | NA | NA | Rv1006 | NA |

| Band protein | NA | NA | Rv1488 | NA |

| FabE10 | NA | NA | Rv0873 | NA |

| Unknown protein | NA | NA | Rv1836c | NA |

| Conserved 35-kDa alanine-rich protein | NA | NA | Rv2744c | NA |

| Trans-acting enoyl reductase | NA | NA | Rv2953 | NA |

| Unknown protein | NA | NA | Rv0831c | NA |

| Hypothetical protease | NA | NA | Rv2224c | NA |

| Glycerol kinase | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_6759 |

| Fatty acid synthase | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_4757 |

| Methoxy mycolic acid synthase | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_0913 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase, NADP dependent | NA | NA | NA | MMEG_1654 |

| Unknown protein | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_6431 |

| Ribosomal protein S1 | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_3833 |

| Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase, alpha subunit | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_1019 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_4323 |

| Citrate synthase I | NA | NA | NA | MSMEG_5672 |

NA, not applicable.

Core surface proteins of M. avium subsp. hominissuis.

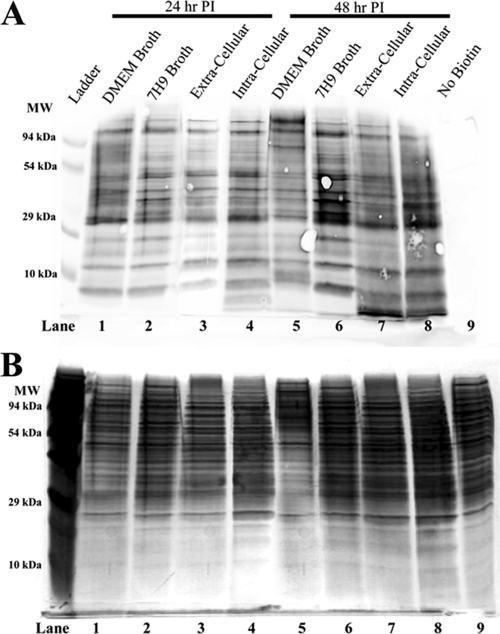

Expanding on the primary goal of characterizing the overall surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis, another objective of this study was to identify major changes within this subproteome that may occur during the initial stages of macrophage infection. While it is known that mycobacteria adapt to pathogenic growth conditions by modulating several aspects of their transcriptome and proteome (1, 40, 58, 84), the scope of this remodeling is poorly understood in M. avium subsp. hominissuis. The Western blot analysis of the biotinylation pattern of total protein from each experimental condition revealed similar overall patterns of labeled proteins between samples (Fig. 3). The lack of a major remodeling of the surface proteome at the early time points assayed in this study is not particularly surprising due to the relatively low growth rate of M. avium subsp. hominissuis. The anti-biotin Western blotting results are also consistent with the mass spectrometry data, which indicate that many of the proteins identified in our analysis are present on the surface of M. avium subsp. hominissuis in most, if not all, of the experimental conditions. These consistently detected proteins may represent a set of core proteins which are likely to be highly abundant, easily detected, and constitutively expressed (Table 1). For the purposes of this study, core proteins were defined as proteins that were detected in all eight of the conditions tested. Approximately 19% (24/125) of the proteins detected in this study met this standard. As expected, a relatively high percentage of these universally detected proteins (42%; 10/24) were also observed on the surface of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, M. tuberculosis, and/or M. smegmatis (Table 1). In contrast to these core proteins, among the remaining M. avium subsp. hominissuis proteins, which may be less abundant or variably expressed, the percentage of overlapping identifications between studies was reduced (26%; 26/101).

Fig 3.

Comparison of biotinylation profiles from all experimental samples. (A) Biotinylation profiles of total protein from each experimental condition. To assess changes in global biotinylation patterns between conditions, aliquots of total protein were analyzed from each sample prior to affinity purification. Samples were from both time points, 24 h (lanes 1 to 4) and 48 h (lanes 5 to 9), and all culture conditions, DMEM (lanes 1 and 5), 7H9 medium (lanes 2 and 6), ECB (lanes 3 and 8), and ICB (lanes 4 and 9). Biotinylation profiles were analyzed by anti-biotin Western blotting. (B) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE gel of the same protein samples.

Table 1.

M. avium subsp. hominissuis 109 surface-exposed proteins detected in all 8 experimental conditions

| UniProt accession no. | EMBL annotation | MAV locus tag | No. of unique peptides found according to culture conditions and time point (h) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7H9 medium |

DMEM |

Extra cellular |

Intra cellular |

|||||||

| 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | |||

| A0Q988_MYCA1 | Superoxide dismutase | MAV_0182 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| CH602_MYCA1 | 60-kDa chaperonin 2 | MAV_4707 | 18 | 11 | 19 | 17 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 12 |

| A0QHU7_MYCA1 | Aconitate hydratase 1 | MAV_3303 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| A0QHY5_MYCA1 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | MAV_3341 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 6 |

| A0QGG5_MYCA1 | Antigen 85-B | MAV_2816 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| EFTU_MYCA1 | Elongation factor Tu | MAV_4489 | 9 | 7 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 8 |

| A0QI11_MYCA1 | LprG protein | MAV_3367 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| A0QM99_MYCA1 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase | MAV_4916 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| A0QER4_MYCA1 | Acyl carrier protein | MAV_2193 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| PGK_MYCA1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | MAV_3340 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| MDH_MYCA1 | Malate dehydrogenase | MAV_1380 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| A0QME6_MYCA1 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | MAV_4963 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| A0QLN4_MYCA1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_4695 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| A0QEY3_MYCA1 | Glutamine synthetase | MAV_2267 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| A0QMX5_MYCA1 | Peroxisomal multifunctional enzyme type 2 | MAV_5146 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| A0QMX6_MYCA1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | MAV_5147 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| ATPA_MYCA1 | ATP synthase subunit alpha | MAV_1525 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 14 |

| ATPB_MYCA1 | ATP synthase subunit beta | MAV_1527 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 10 |

| A0QL09_MYCA1 | 30S ribosomal protein S17 | MAV_4462 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| RS20_MYCA1 | 30S ribosomal protein S20 | MAV_1770 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| A0QJ28_MYCA1 | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | MAV_3744 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| RL19_MYCA1 | 50S ribosomal protein L19 | MAV_3759 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RL21_MYCA1 | 50S ribosomal protein L21 | MAV_1729 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RPOB_MYCA1 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | MAV_4503 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

The distribution of functional annotations among the core proteins was similar to the distribution observed for the complete set of detected proteins. Proteins classified as intermediary metabolism and respiration continued to be the most populous, representing approximately 42% of the total (10/24). Multiple proteins with putative roles in lipid metabolism and cell wall biogenesis were detected under all conditions, such as antigen 85-B (ag85B, MAV_2816) and lipoprotein G (lprG, MAV_3367). Also represented among the identified core proteins are proteins that are implicated in defense, stress response, and virulence, such as superoxide dismutase (sodA) and the 60-kDa chaperonin 2 (groEL2, MAV_4707). Several unexpected proteins were identified under all conditions, including elongation factor Tu (tuf, MAV_4489) and several ribosomal proteins. In most bacteria, elongation factor Tu serves a proof-reading function during ribosomal protein synthesis, a process which normally takes place in the cytoplasmic compartment (75). However, both elongation factor Tu and a range of ribosomal proteins have been consistently identified in studies of surface-exposed proteins in mycobacteria and related Gram-positive bacteria (1, 5, 32, 74, 80, 87).

Surface proteins uniquely detected after contact with macrophages.

In addition to the core proteins, many additional surface-exposed proteins were identified that appeared to be differentially regulated in response to changes in culture conditions or following exposure to macrophage cells. One such subgroup is comprised of proteins whose detection appeared to be dependent on the exposure of the bacterium to macrophages (Table 2). Four proteins were detected in M. avium subsp. hominissuis that had been exposed to macrophage cultures but were not detected in medium-only culture conditions. These proteins were alkylhydroperoxide reductase (ahpC, MAV_2839), isocitrate lyase (aceA, MAV_4682), a universal stress family protein (MAV_2506), and 5-methyl-tetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase (metE, MAV_1262) (Table 2). At least two of these genes, ahpC and aceA, are known to be important mycobacterial persistence factors that are upregulated during mycobacterial infection (22, 56, 59).

Table 2.

M. avium subsp. hominissuis 109 surface-exposed proteins differentially detected after contact with macrophages

| Uniprot accession no. and protein detection statusa | EMBL annotation | MAV locus tag | No. of unique peptides found according to medium and time point (h) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7H9 Medium |

DMEM |

Extra cellular |

Intra cellular |

|||||||

| 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | |||

| Unique | ||||||||||

| A0QGI8_MYCA1 | Alkylhydroperoxide reductase | MAV_2839 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| A0QLM2_MYCA1 | Isocitrate lyase | MAV_4682 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| A0QFL0_MYCA1 | Universal stress protein family protein | MAV_2506 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| METE_MYCA1 | 5-Methyl-tetrahydropteroyltriglutamate–homocysteine methyltransferase | MAV_1262 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Not unique | ||||||||||

| A0QGK7_MYCA1 | ModD protein | MAV_2859 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| A0QJY3_MYCA1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_4070 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A0QLC4_MYCA1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_4583 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A0QHD3_MYCA1 | Universal stress protein family protein | MAV_3137 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| A0QKY3_MYCA1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_4436 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| A0QJ96_MYCA1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_3813 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| A0QKK1_MYCA1 | Putative transposase | MAV_4302 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

Unique refers to proteins that were uniquely detected after macrophage contact.

In contrast to the proteins detected only after exposure to macrophages, several additional proteins appeared to be uniquely absent from the surface of M. avium subsp. hominissuis following exposure to macrophages (Table 2). These proteins included a putative adhesion protein (modD, MAV_2859), a universal stress family protein (MAV_3137), a putative transposase (MAV_4302), and four uncharacterized proteins (MAV_4070, MAV_4583, MAV_4436, and MAV_3813). The best characterized of these proteins, modD, belongs to a family of alanine- and proline-rich proteins that have been described as surface exposed and highly immunogenic (26, 43). In M. tuberculosis, the modD gene is upregulated in response to nutrient deprivation, although the specific nutrients that influence expression remain undefined (8). In M. smegmatis, a close homologue of MAV_3137 has been identified as an abundant surface-exposed protein (74). Universal stress family proteins are a family of at least 10 proteins, many of which are differentially regulated during environmental stress and infection. The M. avium subsp. hominissuis genome encodes at least 4 members of this protein family (66).

Surface proteins differentially detected between phagocytosed and unphagocytosed populations of macrophage-exposed M. avium subsp. hominissuis.

A focus of this study was the identification of proteins whose surface expression was uniquely different between M. avium subsp. hominissuis samples that had been exposed to macrophages and either phagocytosed (ICB) or not phagocytosed (ECB). The identification of differentially regulated, surface-exposed proteins can provide insight into the processes that influence the phagocytosis of M. avium subsp. hominissuis bacilli and their adaptation to the intracellular environment during early infection. Our results highlighted a few proteins that distinguished these two populations of M. avium subsp. hominissuis (Table 3). Four proteins were detected in ICB samples but not in ECB samples of M. avium subsp. hominissuis. These proteins included a 60-kDa chaperonin (groEL1, MAV_4365), a 10-kDa chaperonin (groES, MAV_4366), a putative MarR family protein (MAV_4734), and an uncharacterized protein (MAV_4156). Mycobacterial groEL1 and groES genes are expressed in an operon and are dominant antigens in many Mycobacterium infections (69, 72, 85). These proteins have been previously detected on the surface and in the culture filtrate of several Mycobacterium species, as well as on the more distantly related bacterium Bacillus subtilis (5, 32, 74, 80).

Table 3.

Proteins differentially detected after M. avium subsp. hominissuis 109 exposure to macrophages: phagocytosed versus unphagocytosed

| Uniprot accession no. and detection statusa | EMBL annotation | MAV locus tag | No. of unique peptides found according to medium and time point (h) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7H9 medium |

DMEM |

Extra cellular |

Intra cellular |

|||||||

| 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | |||

| Phagocytosed | ||||||||||

| CH601_MYCA1 | 60-kDa chaperonin 1 | MAV_4365 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| CH10_MYCA1 | 10-kDa chaperonin | MAV_4366 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| A0QK66_MYCA1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_4156 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| A0QLS3_MYCA1 | MarR family protein | MAV_4734 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Unphagocytosed | ||||||||||

| A0QGW2_MYCA1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | MAV_2964 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| EFG_MYCA1 | Elongation factor G | MAV_4490 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| A0QF13_MYCA1 | Putative ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, iron-sulfur subunit | MAV_2297 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Phagocytosed means detected in phagocytosed M. avium subsp. hominissuis but not detected in unphagocytosed M. avium subsp. hominissuis. Unphagocytosed means detected in unphagocytosed M. avium subsp. hominissuis but not detected in phagocytosed M. avium subsp. hominissuis.

Several proteins were also detected in ECB M. avium subsp. hominissuis samples that were largely absent from ICB M. avium subsp. hominissuis samples, although the distinctions tended to be less well defined than those in the preceding comparisons (Table 3). The proteins in this group include a putative Rieske iron-sulfur protein (qcrA, MAV_2297), elongation factor G (efg, MAV_4490), and a putative uncharacterized protein (MAV_2964). Rieske iron-sulfur proteins and several associated dehydrogenases catalyze steps in the metabolism of various carbon sources (10). Homologs of each of these enzymes are known membrane or cell envelope-associated proteins in M. tuberculosis (30). The homolog of mycobacterial qcrA has also been identified as a surface-exposed protein in B. subtilis (80).

DISCUSSION

While previous studies have identified many of the cell membrane, cell wall, and surface-exposed proteins of related mycobacteria (30, 32, 51, 54, 74, 84, 87), little is known specifically about the surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis. In this work, we adapted an existing technology to selectively label and capture surface-exposed proteins. We utilized this approach to profile the surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis and to highlight modulations that may occur in this subproteome during the initial stages of infection. In total, we were able to identify more than 100 putative surface proteins in M. avium subsp. hominissuis. These data shed new light on the surface proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis and highlight some of the proteomic features that may be central to pathogenesis. The overall findings of this study are broadly consistent with the surface proteomes observed in studies of other mycobacteria, which suggests that M. avium subsp. hominissuis shares much of its surface-exposed proteome with related species (Fig. 2B and Table 4). These proteomic similarities lend support to the argument that many of the functions that are essential to mycobacterial pathogenesis (e.g., attachment, the invasion of host cells, and the manipulation of the host immune response) are shared between the various species of Mycobacterium (55).

Surface-exposed proteins that are both constitutively expressed and highly abundant are excellent targets for diagnostic tests and rational vaccine design (38). In this study, we were able to identify a group of 24 core proteins that were detected in all of the tested conditions, both in medium-cultured M. avium subsp. hominissuis and M. avium subsp. hominissuis that had been in contact with macrophages (Table 1). Not unexpectedly, this group includes many proteins that have also been reported to be abundant and surface exposed in other mycobacteria. Many of the core proteins observed in this study are dominant antigens and/or play a central role in mycobacterial pathogenesis, most notably antigen 85-B (ag85b, MAV_2816) and lipoprotein G (lprG, MAV_3367) (18, 83). Antigen 85-B is a mycolyl transferase that is involved in the biosynthesis of the cell envelope (39). It is a well-known surface protein that has been identified as an adhesion protein with a strong affinity for fibronectin (67). The ag85B protein is also a dominant antigen in mycobacterial infection and is released into the phagosome after ingestion by host macrophages (4, 85). Like ag85B, lprG has been previously observed on the mycobacterial surface and has been implicated in mycobacterial virulence (9, 21). Also a dominant antigen of mycobacterial infection, lprG is a posttranslationally glycosylated, surface-exposed lipoprotein (27). It is a toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) agonist and is involved in the modulation of the innate immune response to mycobacterial infection (18, 25).

Several proteins that are normally expected to localize to the cytoplasm also appeared to be abundantly and constitutively represented at the bacterial surface, most notably multiple ribosomal proteins (MAV_4462, MAV_1770, MAV_3744, MAV_3759, and MAV_1729) and elongation factor Tu (tuf, MAV_4489). The question of whether these proteins are truly components of the surface-exposed proteome or merely persistent contaminants remains unresolved. On one hand, ribosomal proteins are abundant and are excellent substrates for trypsin proteolysis because of their abundant lysine and arginine residues. These features may cause samples to become contaminated with easily detected ribosomal peptides. This possibility is supported by the detection of numerous ribosomal proteins in negative-control samples (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). On the other hand, ribosomal proteins have been detected in numerous studies that have profiled the surface-exposed, secreted, and cell wall-associated proteins of mycobacteria and many other species of Gram-positive bacteria (1, 5, 32, 74, 80, 87). In bacteria, some ribosomal proteins may have modified functions beyond the translation of mRNA into protein (79). Similarly, elongation factor Tu has been identified both as a surface-exposed protein and an essential virulence factor for several bacteria (14, 28, 35, 52). Ribosomes may also be complexed with protein-translocating channels, making them partially exposed to the extracellular environment, which may also cause them to be detected in screens of surface-exposed proteins (57).

In addition to the ubiquitously observed core proteins, several sets of proteins appeared to be differentially expressed at the bacterial surface in response to specific culture conditions. M. avium subsp. hominissuis actively endeavors to adhere to host cells, invade them, and establish persistent intracellular infections, a feat which is achieved, in part, by modulating aspects of its surface-exposed proteome (6, 7, 88). This study identified multiple M. avium subsp. hominissuis proteins that appeared to be either uniquely expressed or uniquely absent following exposure to macrophages. Of particular interest are two proteins, alkylhydroperoxide reductase (ahpC, MAV_2839) and isocitrate lyase (aceA, MAV_4682), that were detected only in samples of macrophage-exposed M. avium subsp. hominissuis. The detection of proteins that are differentially regulated following contact with macrophages may help elucidate some of the specific mechanisms that are utilized by M. avium subsp. hominissuis to overcome the host defense responses and nutrient limitation encountered during pathogenic growth. In the case of ahpC and aceA, the genes for both proteins are known to be transcriptionally upregulated in M. tuberculosis during infection, and both have been implicated in mycobacterial pathogenesis (36, 53). Alkylhydroperoxide reductase is a protein that catalyzes peroxide reduction and has been observed on the surface of several bacteria, including M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, M. smegmatis, and B. subtilis (32, 74, 80). It is also known to play a role in isoniazid resistance by compensating for deletions in katG (77), and it is essential for intracellular survival and virulence (53, 86). Experiments using sera harvested from ruminants infected with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and human patients suffering from Crohn's disease indicate that ahpC is a dominant antigen in both cases (64, 65). Consistently with the findings presented here, the ahpC gene in M. tuberculosis has been shown to be highly upregulated after phagocytosis by THP-1 macrophage cells (22). Isocitrate lyase is a key enzyme in the glyoxylate shunt, a metabolic process utilized by mycobacteria to maintain metabolism in carbon-limited conditions (76). The glyoxylate shunt allows the bacteria to directly use fatty acids and acetate as basic carbon sources, a process that is important during nutrient-limited stages of infection. In M. avium subsp. hominissuis, isocitrate lyase has been shown to be uniquely expressed in response to phagocytosis by host macrophages (36). Isocitrate lyase has also been demonstrated to be a necessary persistence factor of infectious mycobacteria in both macrophage and animal models (56, 59), and it has been identified as an ideal drug target for the treatment of tuberculosis infection (60).

Several additional proteins with known roles in mycobacterial pathogenesis were observed to be uniquely present or absent, depending on their interaction with macrophages, including an alanine- and proline-rich protein (modD, MAV_2859) and two chaperonin proteins, groEL1 (MAV_4365) and groES (MAV_4366). The modD protein, which appeared to be uniquely absent following exposure to macrophages, is thought to play a role in bacterial attachment to the extracellular matrix (71). It has been described as a surface-exposed protein that is posttranslationally glycosylated and is a dominant antigen in several infection models (12, 26, 41). The interspecies variation of modD, along with its antigenicity, has been used as the basis for the development of species-specific diagnostic screens (78).

An unexpected observation among the differentially detected proteins was the apparent absence of the groEL1 and groES proteins (MAV_4365 and MAV_4366) on the surface of ECB samples of M. avium subsp. hominissuis despite being detected in all of the other conditions tested in this study. These proteins, which are traditionally identified as chaperone proteins, are also important for virulence in mycobacteria (23). While chaperone proteins are commonly involved in protein folding and stress responses, groEL1 and groES have been implicated in several additional processes in mycobacteria, including cell envelope biosynthesis, persistence, and the invasion of host cells and virulence (34, 46, 63, 69). These proteins appear to be absent from the surface of M. avium subsp. hominissuis samples that had been exposed to macrophages but not phagocytosed, but they are present in all other conditions. This observation provides additional evidence that these proteins have functions related to attachment and invasion. At the same time, important questions remain, such as whether these proteins are removed by the bacteria in the ECB population or whether there is a mixed population (between those with low levels and high levels of these proteins at their surfaces) and the invasion process is sufficient to segregate the two populations.

The treatment of mycobacterial infections is notoriously challenging, but the identification of potential drug targets that are unique for specific phases of infection should be a positive step toward the development of new and improved treatment strategies. This analysis revealed some variations between culture conditions that provide support for the hypothesis that modulations in the expression of dominant antigens during the course of mycobacterial infection undermines the ability of the host to develop an effective adaptive immune response (19, 40). For example, these data suggest that two well-known dominant antigens, ag85A and ag85C (MAV_0214 and MAV_0215), were well represented in M. avium subsp. hominissuis cultured in standard broth medium (7H9) but largely absent from other conditions (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). A potential consequence of this sort of modulation is that a robust overall immune response to mycobacterial infection may be insufficient to clear infection, because the immune response may focus on antigenic targets whose expression is downregulated during the course infection. As a result, the immune system may end up failing to effectively target bacteria that have established a stable infection (87). This type of result also suggests that screens for antigens and immunogens are limited by the culture conditions used to generate the reference protein samples.

Although putative surface and/or secreted proteins are a small fraction of the mycobacterial proteome, they represent a large portion of known bacterial antigens (3, 37, 38, 45, 87). This is largely because the surface-exposed molecules of the bacterium are primarily what the immune system sees when it targets a pathogen. Antibodies are most likely to be effective if their target antigens are easily accessible, surface-exposed molecules. The comprehensive profiling of the surface proteome of a pathogen like M. avium subsp. hominissuis can generate a list of viable targets for rational vaccine design. A central challenge in designing both vaccines and diagnostic tests is identifying targets which are both abundant and specific. As a result of the similarities between the surface-exposed proteomes of different mycobacteria, cross-reactivity among mycobacterial antigens is a common problem (68). The comprehensive profiling of M. avium and other mycobacteria can help resolve this issue by identifying subsets of potential targets that may be unique to a particular species of mycobacteria. Additionally, the identification of targets that may also be unique to a particular phase of pathogenesis (e.g., intracellular growth) is of significant importance. In the case of pathogenic Mycobacterium, many of which establish long-term latent infections, this methodology could assist the development of therapeutic vaccines that can aid in the treatment of chronic infection.

While our analysis of the surface-exposed proteome of M. avium subsp. hominissuis was highly consistent with previous proteomic profiles of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (32), M. smegmatis, and M. tuberculosis (74), the methods used in each study are significantly different, which inevitably affects the respective results (Fig. 2B and Table 4). The referenced studies of mycobacterial surface proteins employed trypsin shaving (M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis) or the selective solubilization of the cell envelope (M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis) to isolate surface-exposed peptides and proteins for analysis. In contrast, this study used the covalent labeling of surface-exposed proteins with biotin, followed by affinity purification. The primary challenge of each approach is to efficiently purify the target molecules while minimizing background contamination. The various capacities of each experimental approach to overcome this challenge may explain some of the observed similarities and differences between the respective data sets.

In addition to the proteins highlighted in Tables 1 to 3, numerous other putative surface-exposed proteins were identified that did not fit into well-defined groups based on the conditions in which they were detected (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Most of these proteins were detected in only a few conditions with apparently random distribution. The hit-or-miss nature of these protein identifications highlights the fundamental limitation of the conclusions that can be drawn from these data. The peptide mixtures analyzed in each sample are both complex and variable. Most of the protein identifications are dependent on the identification of a couple of peptides, which is a fingerprint and not a comprehensive profile. In addition, many of these peptides are not abundant and near the detection threshold. Sample handling during protein extraction, affinity purification, enzymatic digestion, and peptide cleanup introduces variability that affects which peptides are ultimately detected with confidence and which are not. Therefore, while positive identifications have a good probability of being accurate, a failure to detect a protein does not necessarily indicate that it is truly absent. Because of this limitation, the data presented here cannot be considered a comprehensive or exhaustive profile.

There are two additional limitations of the data presented in this study that should be taken into account. First, the fractionation of total protein, on the basis of solubility, from biotinylated M. avium subsp. hominissuis indicated that some proteins were not effectively solubilized by the buffers used in this study (Fig. 1). This result suggests that some surface proteins are poorly represented or are not identified by this analysis. For example, no members of the PPE and PE families of mycobacterial proteins were observed in this study, although many among them are known to be surface-exposed proteins in many species of Mycobacterium, including the closely related M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (29, 32, 61). Overall, many proteins that are expected to be surface exposed were not identified in this analysis (62). Subsequent work in our laboratory has shown that several of these proteins are indeed present on the surface of M. avium subsp. hominissuis, but the efficient solubilization and purification of these proteins require the presence of additional reagents, such as 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) or SDS (data not shown). A similar effect of solubility may explain the minimal overlap of identified proteins between the two previous studies used in this study as comparative references for mycobacterial surface-exposed proteins (Fig. 2B and Table 4). For example, whereas the trypsin shaving of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis identified 3 PPE family proteins on the surface of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, the solubilization of the M. tuberculosis outer membrane did not identify any members of this family, although they are known to be prominent members of the surface proteome of M. tuberculosis (2, 13, 29, 32). The likely cause of this discrepancy is the bias of the solubilization method toward proteins that are more easily solubilized. While the results generated here correlate well with the results of both previous methods, it is nonetheless apparent that a population of proteins remains refractory to each method of analysis.

The final limitation of note applies to all of the methods that use trypsin to generate peptides for proteomic analysis. Trypsin cleaves after lysine and arginine, a fact which can cause some proteins to be overrepresented and others underrepresented. Complicating matters, the biotinylation of lysine side chains inhibits cleavage at that residue, which may further contribute to the underrepresentation of lysine-poor proteins in the data set. Many DNA-binding and ribosomal proteins are rich in both lysine and arginine, which make them excellent substrates for trypsin and may cause them to appear to be more abundant than they truly are. Along with their general abundance, this feature may explain why ribosomal proteins are commonly identified in profiles of surface-exposed proteins, including in this study. While beyond the scope of this study, the limitations discussed here may be overcome in future analyses through improvements in protein extraction and purification protocols, the use of alternative protease enzymes to create complementary sets of peptides, improved peptide cleanup, and optimized LC-MS/MS technologies.

The selective labeling of surface proteins to facilitate their purification and identification has been employed in studies analyzing both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. In this report, we streamlined the technology and adapted it for use in the study of the opportunistic pathogen M. avium subsp. hominissuis. In total, this study identified more than 100 putative surface-exposed proteins. The comparison of data derived from M. avium subsp. hominissuis cultured in both standard media and conditions simulating the initial stages of infection highlighted several groups of proteins that may be uniquely modulated during early pathogenesis. These analyses provide a unique insight into the molecular mechanisms of M. avium subsp. hominissuis pathogenesis that are mediated by surface-exposed proteins. In turn, the data and methods presented here can contribute to the development of better tools for the diagnosis and treatment of mycobacterial disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant AI RO1 41399.

We thank Denny Weber for manuscript assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 March 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdallah AM, et al. 2008. The ESX-5 secretion system of Mycobacterium marinum modulates the macrophage response. J. Immunol. 181:7166–7175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abdallah AM, et al. 2009. PPE and PE_PGRS proteins of Mycobacterium marinum are transported via the type VII secretion system ESX-5. Mol. Microbiol. 73:329–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahk YY, et al. 2004. Antigens secreted from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: identification by proteomics approach and test for diagnostic marker. Proteomics 4:99–3307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beatty WL, Russell DG. 2000. Identification of mycobacterial surface proteins released into subcellular compartments of infected macrophages. Infect. Immun. 68:6997–7002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beck HC, et al. 2009. Proteomic analysis of cell surface-associated proteins from probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 297:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bermudez LE, Petrofsky M, Goodman J. 1997. Exposure to low oxygen tension and increased osmolarity enhance the ability of Mycobacterium avium to enter intestinal epithelial (HT-29) cells. Infect. Immun. 65:3768–3773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bermudez LE, Shelton K, Young LS. 1995. Comparison of the ability of Mycobacterium avium, M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis to invade and replicate within HEp-2 epithelial cells. Tuber. Lung Dis. 76:240–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Betts JC, Lukey PT, Robb LC, McAdam RA, Duncan K. 2002. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol. Microbiol. 43:717–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bigi F, et al. 2004. The knockout of the lprG-Rv1410 operon produces strong attenuation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 6:182–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bott M, Niebisch A. 2003. The respiratory chain of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 104:129–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brodt HR, Enzensberger R, Kamps BS, Keul HG, Helm EB. 1997. Impact of disseminated Mycobacterium avium-complex infection on survival of HIV-infected patients. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2:106–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cho D, Shin SJ, Collins MT. 2010. B-cell epitope specificity of carboxy terminus of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis ModD. J. Immunoassay Immunochem. 31:181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daleke MH, et al. 2011. Conserved Pro-Glu (PE) and Pro-Pro-Glu (PPE) protein domains target LipY lipases of pathogenic mycobacteria to the cell surface via the ESX-5 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 286:024–19034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dallo SF, Kannan TR, Blaylock MW, Baseman JB. 2002. Elongation factor Tu and E1 beta subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex act as fibronectin binding proteins in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1041–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Danelishvili L, et al. 2007. Identification of Mycobacterium avium pathogenicity island important for macrophage and amoeba infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:038–11043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Lima CS, et al. 2009. Heparin-binding hemagglutinin (HBHA) of Mycobacterium leprae is expressed during infection and enhances bacterial adherence to epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 292:162–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Miguel N, et al. 2010. Proteome analysis of the surface of Trichomonas vaginalis reveals novel proteins and strain-dependent differential expression. Mol. Cell Proteomics 9:1554–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drage MG, et al. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoprotein LprG (Rv1411c) binds triacylated glycolipid agonists of Toll-like receptor 2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:1088–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Early J, Bermudez LE. 2011. Mimicry of the pathogenic mycobacterium vacuole in vitro elicits the bacterial intracellular phenotype, including early-onset macrophage death. Infect. Immun. 79:2412–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elia G. 2008. Biotinylation reagents for the study of cell surface proteins. Proteomics 8:4012–4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farrow MF, Rubin EJ. 2008. Function of a mycobacterial major facilitator superfamily pump requires a membrane-associated lipoprotein. J. Bacteriol. 190:1783–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fontan P, Aris V, Ghanny S, Soteropoulos P, Smith I. 2008. Global transcriptional profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during THP-1 human macrophage infection. Infect. Immun. 76:717–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galli G, Ghezzi P, Mascagni P, Marcucci F, Fratelli M. 1996. Mycobacterium tuberculosis heat shock protein 10 increases both proliferation and death in mouse P19 teratocarcinoma cells. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 32:446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia J, et al. 2009. Comprehensive profiling of the cell surface proteome of Sy5Y neuroblastoma cells yields a subset of proteins associated with tumor differentiation. J. Proteome Res. 8:3791–3796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gehring AJ, Dobos KM, Belisle JT, Harding CV, Boom WH. 2004. Mycobacterium tuberculosis LprG (Rv1411c): a novel TLR-2 ligand that inhibits human macrophage class II MHC antigen processing. J. Immunol. 173:2660–2668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gioffre A, et al. 2009. Characterization of the Apa antigen from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis: a conserved Mycobacterium antigen that elicits a strong humoral response in cattle. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 132:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonzalez-Zamorano M, et al. 2009. Mycobacterium tuberculosis glycoproteomics based on ConA-lectin affinity capture of mannosylated proteins. J. Proteome Res. 8:721–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Granato D, et al. 2004. Cell surface-associated elongation factor Tu mediates the attachment of Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC533 (La1) to human intestinal cells and mucins. Infect. Immun. 72:2160–2169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Griffiths TA, Rioux K, De Buck J. 2008. Sequence polymorphisms in a surface PPE protein distinguish types I, II, and III of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1207–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gu S, et al. 2003. Comprehensive proteomic profiling of the membrane constituents of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain. Mol. Cell Proteomics 2:1284–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He Z, De Buck J. 2010. Cell wall proteome analysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis strain MC2 155. BMC Microbiol. 10:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. He Z, De Buck J. 2010. Localization of proteins in the cell wall of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis K10 by proteomic analysis. Proteome Sci. 8:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hempel K, et al. 2010. Quantitative cell surface proteome profiling for SigB-dependent protein expression in the human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus via biotinylation approach. J. Proteome Res. 9:1579–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Henderson B, Lund PA, Coates AR. 2010. Multiple moonlighting functions of mycobacterial molecular chaperones. Tuberculosis 90:119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holub M, et al. 2010. Comparative study of the life cycle dependent post-translation modifications of protein synthesis elongation factor Tu present in the membrane proteome of streptomycetes and mycobacteria. Folia Microbiol. 55:203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Honer Zu Bentrup K, Miczak A, Swenson DL, Russell DG. 1999. Characterization of activity and expression of isocitrate lyase in Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 181:7161–7167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hughes V, et al. 2008. Immunogenicity of proteome-determined Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis-specific proteins in sheep with paratuberculosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:1824–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jagusztyn-Krynicka EK, Roszczenko P, Grabowska A. 2009. Impact of proteomics on anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) vaccine development. Pol. J. Microbiol. 58:281–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katsube T, et al. 2007. Control of cell wall assembly by a histone-like protein in mycobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 189:8241–8249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kruh NA, Troudt J, Izzo A, Prenni J, Dobos KM. 2010. Portrait of a pathogen: the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteome in vivo. PLoS One 5:e13938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kumar P, Amara RR, Challu VK, Chadda VK, Satchidanandam V. 2003. The Apa protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis stimulates gamma interferon-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from purified protein derivative-positive individuals and affords protection in a guinea pig model. Infect. Immun. 71:1929–1937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kunnath-Velayudhan S, et al. 2010. Dynamic antibody responses to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:14703–14708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laqueyrerie A, et al. 1995. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the apa gene coding for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 45/47-kilodalton secreted antigen complex. Infect. Immun. 63:4003–4010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lew JM, Kapopoulou A, Jones LM, Cole ST. 2011. TubercuList–10 years after. Tuberculosis 91:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li Y, et al. 2010. A proteome-scale identification of novel antigenic proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis toward diagnostic and vaccine development. J. Proteome Res. 9:4812–4822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li YJ, Danelishvili L, Wagner D, Petrofsky M, Bermudez LE. 2010. Identification of virulence determinants of Mycobacterium avium that impact on the ability to resist host killing mechanisms. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:8–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin J, Huang S, Zhang Q. 2002. Outer membrane proteins: key players for bacterial adaptation in host niches. Microbes Infect. 4:325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lindahl G, Stalhammar-Carlemalm M, Areschoug T. 2005. Surface proteins of Streptococcus agalactiae and related proteins in other bacterial pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:102–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lu B, McClatchy DB, Kim JY, Yates JR., III 2008. Strategies for shotgun identification of integral membrane proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomics 8:3947–3955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mahfoud M, Sukumaran S, Hulsmann P, Grieger K, Niederweis M. 2006. Topology of the porin MspA in the outer membrane of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Biol. Chem. 281:5908–5915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Malen H, Berven FS, Fladmark KE, Wiker HG. 2007. Comprehensive analysis of exported proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Proteomics 7:1702–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marques MA, Chitale S, Brennan PJ, Pessolani MC. 1998. Mapping and identification of the major cell wall-associated components of Mycobacterium leprae. Infect. Immun. 66:2625–2631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Master SS, et al. 2002. Oxidative stress response genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of ahpC in resistance to peroxynitrite and stage-specific survival in macrophages. Microbiology 148:3139–3144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mawuenyega KG, et al. 2005. Mycobacterium tuberculosis functional network analysis by global subcellular protein profiling. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:396–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McGarvey J, Bermudez LE. 2002. Pathogenesis of nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Clin. Chest Med. 23:569–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McKinney JD, et al. 2000. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406:735–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mitra K, et al. 2005. Structure of the E. coli protein-conducting channel bound to a translating ribosome. Nature 438:318–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Monahan IM, Betts J, Banerjee DK, Butcher PD. 2001. Differential expression of mycobacterial proteins following phagocytosis by macrophages. Microbiology 147:459–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Munoz-Elias EJ, McKinney JD. 2005. Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence. Nat. Med. 11:638–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murphy DJ, Brown JR. 2008. Novel drug target strategies against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:422–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Newton V, McKenna SL, De Buck J. 2009. Presence of PPE proteins in Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates and their immunogenicity in cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 135:394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffmann C, Engelhardt H. 2010. Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins. Trends Microbiol. 18:109–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ojha A, et al. 2005. GroEL1: a dedicated chaperone involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis during biofilm formation in mycobacteria. Cell 123:861–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Olsen I, Reitan LJ, Holstad G, Wiker HG. 2000. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductases C and D are major antigens constitutively expressed by Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 68:801–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Olsen I, Wiker HG, Johnson E, Langeggen H, Reitan LJ. 2001. Elevated antibody responses in patients with Crohn's disease against a 14-kDa secreted protein purified from Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 53:198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]