Abstract

The objective of the study is to assess views of age related changes in sexual behavior among married Thai adults age 53 to 57. Results are viewed in the context of life course theory. In-depth interviews were conducted with 44 Thai adults in Bangkok and the four regions of Thailand. Topics covered include changing sexual behavior with age, adjustment to this change, gender differences in behavior, attitudes toward commercial sex and other non-marital sexual partners, and condom use. Most respondents were aware of this change and saw a decrease in sexual activity and desire more often among women compared to men. At the same time, many respondents viewed sexuality as important to a marriage. Some respondents accepted the decrease in sexual activity and focused more on work, family and temple activities. Thai Buddhism was seen as an important resource for people who were dealing with changes due to aging. Other persons turned to other partners including both commercial and non-commercial partners. The influence of the HIV epidemic that began in the 1990s was seen in concerns about disease transmission with extramarital partners and consequent attitudes toward condom use. The acceptability of extramarital partners in the family and community ranged from acceptance to strong disapproval of extramarital relationships

Keywords: Buddhism, sexuality, Thailand, aging, HIV

Introduction

Many studies show a declining frequency of sexual activity with age in Asia as well as other areas of the world (Knodel and Chayovan 2001; Lindau et al. 2007; Bachman and Lieblum 2004). Many reasons have been discussed for this decline in activity. First, there may be physical problems that come with age, because health and changes in physiology can affect the sexual response of men and women as people age (Bachman and Lieblum 2004; Nicolosi et al. 2004). Other factors such as time spent on work and caring for children as well as changes in relationships over time and differences in views of sexuality by different generations also play a role in this decline (Carpenter, Nathanson & Kim, 2009).

Studies of midlife and older adults in other countries have generally shown a decline in activity and some acceptance of this but studies have also shown that sexuality is important to older adults (Gott & Hinchliff, 2003; Carperter, Nathanson & Kim, 2009; Heiman et al., 2011; Moore, 2010). In a Japanese study, sexual desire was found to have a continuing importance in later life, particularly among men. In a study of British adults age 50–92 years, both male and female respondents who had a current partner attributed some importance to sex with many rating sex as “very important” (Gott & Hinchliff, 2003). Finally, in a study of midlife and older adults age 40–70 in five countries, sexual functioning was important to relationship satisfaction for both men and women (Heiman et al., 2011).

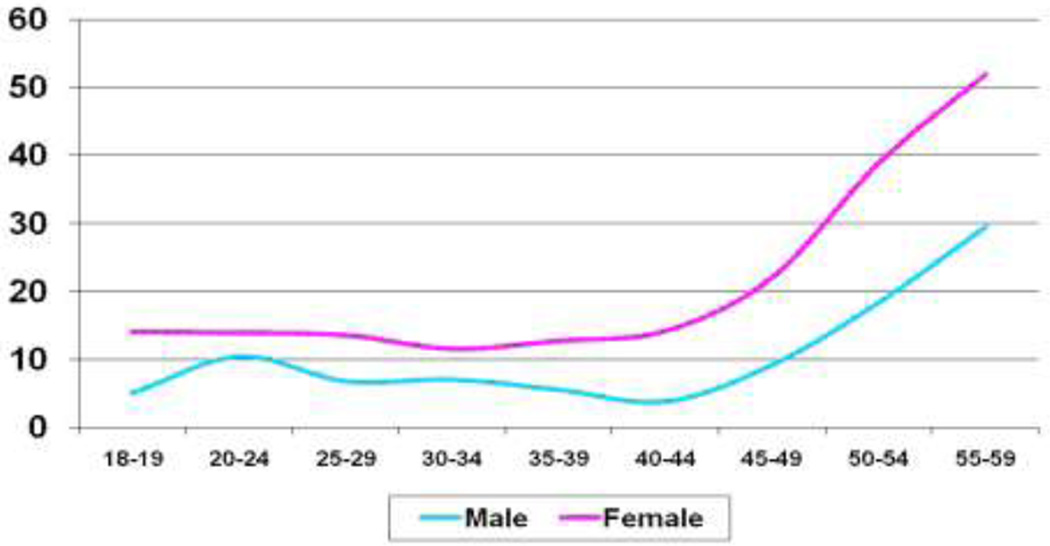

Data from the 2006 National Survey of Sexual Behavior provided data on sexual behavior among older adults on Thailand (Chamratrithirong et al. 2007; Ford and Chamratrithirong 2009). Most Thai adults in their fifties (89% of men and 81% of women) had a partner (usually a marital partner) that they were living with. Sixty six percent of men in their fifties with a cohabiting partner and 69% of women in their fifties with a cohabiting partner reported sex with this partner at least once a week during the last three months. Other couples in their 50s (18% of men and 27% of women with cohabiting partners) reported no sex in the last three months with these cohabiting partners. Figure 1 shows the pattern of declining sexual activity among cohabiting couples by age. In this Thai population, decreases in the frequency of sex occurred beginning in the mid 40s and became large in the fifties. At the same time, only a small percent of men (3%) and less than one percent of women in their fifties reported sex with partners that they were not living with.

Figure 1.

Percent of men and women with a live in partner who reported no sex in the last three months.

Previous work on sexuality in Thailand has asserted that Thais view sexuality as being different for men and women (Knodel et al. 1996; VanLandingham et al. 1998). Males may have a strong innate sex desire with a preference for variety, while females are seen to have weaker desires for sex and stronger self control. In a national survey of persons age 50 and older in Thailand, both sexual desire and sexual activity declined faster for women than for men and that women tend to underreport sexual activity compared to men (Knodel and Chayovan 2007).

Qualitative research on extramarital relationships among Thai men has noted the importance of the peer group in promoting both premarital and extramarital visits to sex workers (VanLangingham et al. 1998; VanLandingham and Knodel 2007). Thai men may spend time socializing with their male friends and these occasions may include alcohol use and visits to sex workers. Visits to sex workers by married men were seen as acceptable to some Thai men, though others spoke out against this. In a qualitative study of unmarried Thai men in their fifties, some men did visit commercial sex workers, while many preferred not to because of declining interest, financial costs, perceived social disapproval, and interests in other activities such as spending more time at Buddhist temples (VanLangingham & Knodel 2007).

As documented by the 2006 National Survey of Sexual Behavior (Ford & Chamratrithirong 2009), sexual behavior has changed rapidly over the last 20 years, particularly among young persons. Compared to earlier generations where young adults’ sexual relationships were mainly with marital partners or sex workers, young adult men and women in Thailand now engage in a range of sexual relationships, with a decreased emphasis on commercial sex. It is unclear if this change in attitudes and behavior regarding sexuality among young adults has also occurred among older adults making a wider variety of sexual relationships more acceptable. Older adults in Thailand have lived through the era of an increasing number of HIV cases in Thailand and a strong prevention program and it is unclear how the strong HIV prevention programs conducted in Thailand in recent years may have affected views of sexuality among older adults. A 1999 study of older adults in their fifties found that knowledge of HIV transmission and prevention was lower in persons in their fifties compared to younger adults (Im-Em et al 2002).

In summary, studies of aging and sexuality in Thailand and other countries have shown that there is a decline in the frequency of sex with aging, although sexual activity still remains important to many persons. In Thailand, due to the impact of the AIDS epidemic and due to development, patterns of sexual behavior have changed. Among younger adults and adolescents, there is less emphasis on commercial sex and more emphasis on unpaid partners, both casual and intimate. While qualitative research has been conducted with younger adults and older single men on current views of sexuality, there have not been qualitative studies of married Thai adults persons at midlife. This study adds to the literature by focusing on views of sexuality among married persons in their early fifties, a time when a reduction in sexual activity becomes marked (Ford & Chamratrithirong, 2009). Persons in this age group are making a transition from mid to later life where the place of sexuality may be different.

In our conceptual framework, we view changes with sexuality due to age through elements of life course theory (Elder, 1985, 1998). As a general theory of human development, life course theory emphasizes the salience of the social, cultural and historical context on individual’s lives over time. The Thai adults in this study have experienced a rapid rise in HIV infection in the 1990s followed by an intensive HIV prevention program. In addition, sexual behavior among young adults has shifted from a focus on marital and commercial partners to a wider variety of relationships. These changes in personal and community norms among younger adults in Thailand may have an influence on the norms and behavior of older adults.

A second aspect of life course theory relevant to this analysis is the principle of human agency (Elder, 1998). “Individuals construct their own life course through the choices and actions they take within the opportunities and constraints of history and social circumstances”(Elder, 1985, 1998). Previous Thai research on male sexuality relevant to this concept showed that while where there may be peer pressure to participate in extramarital sex, the ultimate responsibility for participating in commercial sex was up to the individual himself (VanLandinham et al., 1998). Hence, this aspect of life course theory may also be consistent with Thai choices in sexual behavior.

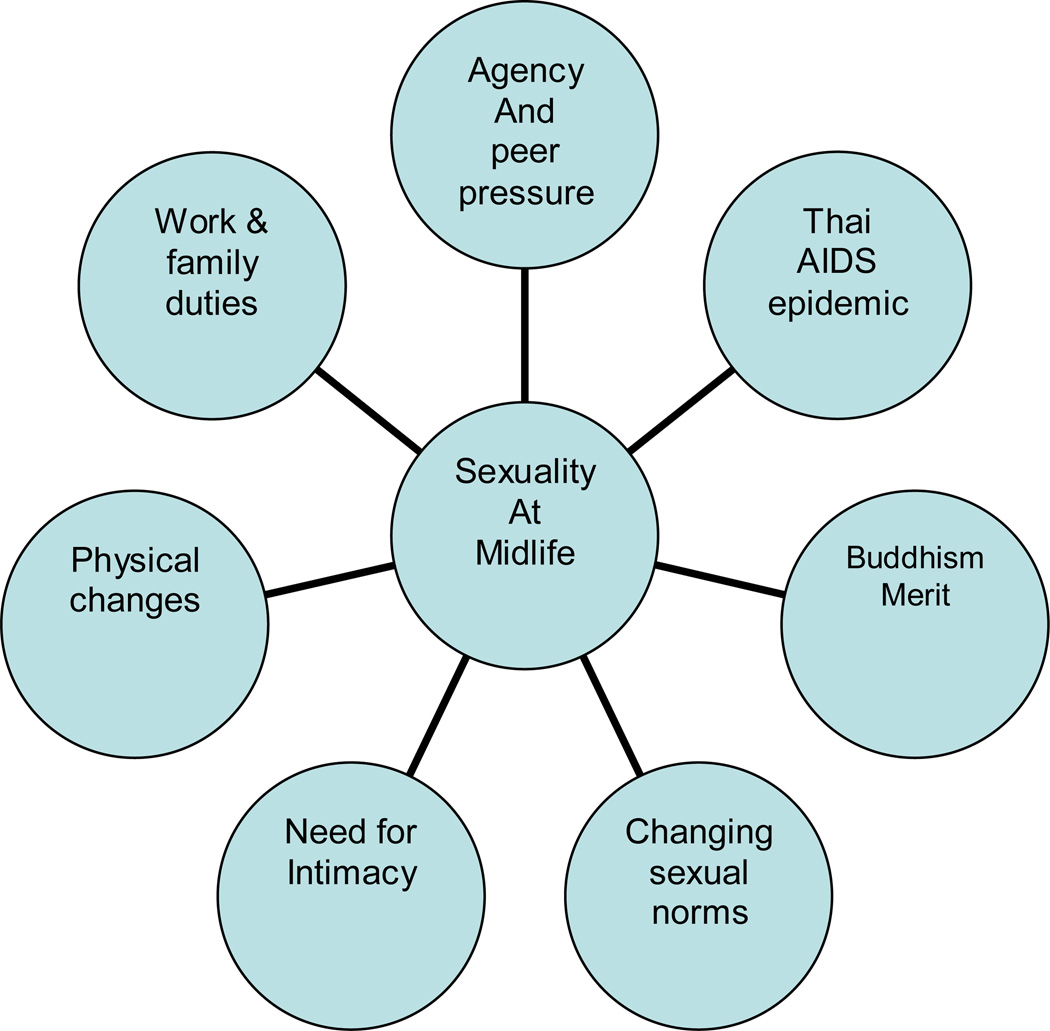

The objective of this paper is to examine, through a qualitative study, views of changing sexuality among married Thai adults in their early to mid fifties. Figure 2 shows the factors from life course theory and the literature that may affect midlife sexual norms and behavior. From life course theory, we expect an influence of the Thai HIV epidemic as well as changes in sexual norms from when they were younger. The literature shows an influence of peers on male sexuality, although agency or individual choice should play a role. In Thailand, Buddhism with the need to make merit for the next life and an expected involvement in temple activities may play a role. Based on the international literature, other factors may include increased work and family duties, physical changes, and a need for intimacy.

Figure 2.

Factors affecting Marital sexuality at midlife.

Methods

In-depth interviews were conducted with a sample of 22 men and 22 women age 53–57. This age group was selected because quantitative data showed that the decline in sexual frequency becomes larger in this age group. Twelve interviews were conducted In Bangkok and eight interviews were conducted in each of the four regions of Thailand (North, Northeast, Central and South). In Thailand, community offices maintain registers of community residents including their locations, age, gender, and education level. These registers are available to the public. Respondents meeting the age, gender and marital status criteria of average education for the area were selected randomly from the registers.

The interview guide was developed in central Thai language. The interview guides included questions on changing sexual behavior with age, adjustment to this change, gender differences in behavior, attitudes toward commercial sex and other non-marital sexual partners, and attitudes toward HIV testing and condom use. The interviewers were native Thai speakers and were matched with respondents by gender. In each region, interviewers who were familiar with the local dialect conducted the interviews. All of the interviewers had extensive experience with the interview process. They were trained to conduct the interviews non-judgmentally and to probe for depth in answers to the questions and to allow time for the respondents to give extended answers to the questions. Interviews were conducted in a private place in the community where others could not overhear the respondents’ answers. Respondents were interviewed once for 1–2 hours.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed in central Thai language and then translated into English. These transcripts were reviewed by the investigators and entered into a software package for qualitative analysis. The English speaking and the Thai investigators participated in the analysis and the interpretation of the data. Open coding was used to explore and organize the transcript data into broad conceptual domains. Codes were reviewed and revised to identify common themes and then interpreted by the investigators. The analysis followed principles of grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss 2007). During analysis, the Thai transcripts were available to review the translation and to confirm appropriate interpretation of the data. IRB approval for the study was obtained after review of the study design at Mahidol University and at the University of Michigan.

Results

The respondents ranged in age from 53 to 57. All were currently married and half were male and half female. Most of the respondents living in the Northeast and Central regions were involve din farming and wage labor, those in the South were involved in work on rubber plantations and construction, and those in Bangkok were involved in civil service, business, trade and the military.

Observations: Declining frequency of sex with age and reduced female interest

Confirming what has been found previously (Ford & Chamratrithirong, 2009), most of the persons interviewed reported a declining frequency of sex with age. Most often it was reported that women (and some men) became less interested in sex as they became older and reached menopause. This view was present among men and women in all regions.

“If you ask me about men and women age 40–49, I am sure I can see differences between men and women. To me, men tend to have a lot (sexual relations) but for women they will draw back from sex. Sex will decline at this point… When it comes to 40 years old, according to our friends, talking, our friends will say ‘Oh, don’t wake me up, I’m not awake. Go.’ Some tell the husband ‘Go Away, Go Go Go.” That is to say, from listening to my friends, it is like saying that men will have a high ‘graph” (on sex), but for women it will decline.”

Bangkok female

“Sex is like a lamp that uses a fuel. People don’t have sex demand as the fuel of the lamp is gone. It becomes a soft light.”

Bangkok female

“Women 50 years old stop having a period so they don’t want to have sex.”

Bangkok male

Reasons for this decline in sexual activity

Increased responsibility for work, children, decrease in stamina

Respondents reported several reasons for the decline in frequency of sex. Reasons for this decline in frequency of sex included boredom with sexual activity and the demands of work and childcare. Midlife is a time when individuals have a lot of responsibility for work and others. Respondents reported fatigue from working and taking care of children. The need to deal with these daily tasks distracted some respondents from sexual activity. Decreased stamina resulting in more fatigue from daily activities was also seen to acted sexual activity. Persons reported feeling tired after the day’s work.

“Women (reduce demand) but men always have sex demand. In the society, women stop having sex. They work hard so they don’t care for it. They are happy when they see the children.”

Bangkok male

“For me, when I just married about 32–40 years old, my job was very good also like having sex because I was happy. And, if I had a mistake in job, the feeling in having sex will become lesser because I have to think about work. It’s not like before.”

Southern male

“She (my wife) is a teacher and doesn’t have time. She works seven days. I’m tired because I work every day. My wife and I don’t like to stay home.”

Bangkok male

“For women, after they have children, their needs of sexual relations will be dropped. (For men) I think their needs have dropped because they might be tired from work and need to take more rest instead.”

Central female

“Our health is not as strong as before, it is tiring. I have been working for the whole day. As soon as I arrive home, I take a shower and go to sleep.”

Central male

Physical problems with having sex

As expected from the literature, physical problems with having sex were reported by the respondents. Changes due to menopause as well as difficulty in reaching orgasm and maintaining erections were noted “At that time (when young), they say ‘the bird does not finish drinking water yet’ (the orgasm comes too fast, faster than the time it takes for the bird to drink water). But now (at older ages) it is not like that. It turns out to be deadly boring. It never finishes (cannot reach orgasm).”

(Interviewer: “You mean the bird cannot sing? (cannot get an erection?))

“Even though it sings (becomes erect) it does not easily come out (ejaculate)”

Southern male

“I used to ask once. I asked “have you felt?” She replied no. Sometimes, when we are having sex, she doesn’t feel, so I don’t feel.”

Central male

When should a couple stop having sex?

These Thai adults in their fifties had varied opinions on when a couple should stop having sex. Some thought that they should stop in their sixties, while others though that it should be up to the couple and their health. As above, many reported that females were likely to stop when they were younger than males.

“I think men have their demand until they die and women should stop their demands at 60 years old.”

Bangkok female

“It depends on their health and how they look after themselves. Some people don’t look after themselves so they get sick and don’t’ have sex demand. Adult people in 50–60 ages are able to have sex if they have a good health and look after themselves.”

Bangkok male

Sexual Activity: Importance to marriage

The study respondents were also asked if sexuality was important to the marriage. Opinions differed about this topic. Some respondents reported that a declining frequency of sex was fine because they live as friends and go to the temple often. There were other ways such as caring for each other, to keep intimacy in a marriage. As mentioned above, Thai Buddhism may be an important factor in adjusting to this change. The respondents became more involved in temple activities and making merit for the next life. Others reported that there were other ways of maintaining intimacy in their marriage such as walking closely together and taking care of each other.

“Some people don’t care about it. They want to live with a happy family and do their duty best but some people they really want to have sex”.

Bangkok female

“We don’t have sex much because we’re older. We live by helping each other”.

Northern female

“We have married for long time, so we live like brother and sister.”

“Sex is not important (for older women) maybe because the couple may be living together as friends, or they can focus on studying Dharma (religious principles), making merit and donations, observing precepts, listening to preaching, and more activities like that. We think that these matters are important to help prepare to die and be in the next life. We will do good things according to Buddhism. We keep doing good and making merit. In the next life, we will receive (these good things). Therefore, today, sex is not necessary. It is more like we live as friends and keep helping each other.”

Bangkok female

Northern male

Other respondents thought that sex was important for the survival and intimacy in their marriage. Sex was important for closeness as a couple and was a part of the best marriages. Still others thought that having sex was necessary to keep the husband from going to sex workers or other partners.

“Sex is important for married life, some couples divorce because of this”

Northeast male

“Having sex shows that we still love each other”

Northern male

“Yes (sex) is important if they are able to because it shows the deep relationship between a couple.”

Central female

“(The husband) can lead by the hand when they go out or walk across the street or put his arm around her shoulder to express his love more than having sex. It (not having sex) does not mean that they do not love each other anymore but they express their generosity in ways such as looking after each other when they are sick”.

Bangkok female

“Some men still want to have sex but their women don’t want anymore so they find the other way out such as going to look for other women. Men think that sex can maintain their family but women don’t think like that. Women want generosity and sympathy to maintain their family”.

Bangkok female

“If the man wants to have sex, but the woman does not want to, and refuses to have sex, and does not give sexual pleasure to men or if women want to have sex, and men have no desire, it may lead to breaking up (the marriage)”.

Southern male

“My husband and I are living as friends. We consult each other. On weekends we will go to the temple to make merit, to chant religious prayers, and to do meditation. These are things that we do. Sexual relations have declined. But in other families, men may feel that staying at home with the wife is boring. Sometimes (they feel that) wives have no sexual desire and the husbands do not understand why we are not sexually aroused. So they (the husbands) want to try it with other types of women, i.e. outside in order to see whether they still have a man’s instinct. They will go to find sexual pleasure outside the home. Then all the problems come.”

Bangkok female

Sexual partners outside of marriage

Because the preference of timing of stopping having sex can be different between husbands and wives as well as a tradition of acceptance of extramarital partners for men, the issue of extramarital sex emerged. Many respondents reported that they and their communities would not be accepting of extramarital partners. They said that people would hate or not talk with a man who had other partners.

Other persons were more accepting of men having other partners, particularly commercial partners. They viewed the use of commercial partners as part of a man’s life. However, if men did go to sex workers, they were expected to be discreet about this. Male respondents in the Bangkok area were more accepting of commercial relationships than were persons in other areas. In a large city, it is easier to have commercial partners without it being known among family and friends. Concerns were also expressed about the possibility of acquiring HIV infection in commercial relationships. A man could contract HIV from a commercial partner and then infect his wife.

“I don’t want to have sex so he goes outside to find the young girls but I don’t know if they are infected with AIDS. They sleep with many guys so they don’t know who they are infecting… It is not proper that they go to the brothel and still sleep with their wives. It’s very risky.”

Bangkok female

Sex at a brothel for an older man

The opinions of the respondents related to sex at a brothel or other commercial sex for a man in his fifties varied among respondents. Many reported that it was not acceptable, that it would lead to problems with the family, divorce, and it would expose the family to HIV infection. Others held a different view. Visiting prostitutes was a common behavior for men and was simply part of a man’s life and should not be seen as a threat to the family.

“In my neighbors’ opinions (about men going to prostitutes), it’s a normal thing like a routine. It becomes the part of their life that they cannot do without it. They think it is part of their life.”

Bangkok female

“It is their right (to go to brothels), but for me, I think they should have better activities to do.”

Northeast male

“I saw a house where the man didn’t work but his wife did. He went to play snooker and in the evening he took a girl from there to sleep with at his house. He is the person the neighbors don’t talk to because o f his behavior. Therefore, it shows that our society doesn’t accept this man’s behavior.”

Bangkok female

“Of course, (older people are) different in power and the amount of times of having sex. Sometimes, they can fall in love with others because they are just only old in their body, not their heart.”

Northern male

“Many people hate him because he went to a brothel. They didn’t want to respect him.”

Northern male

“I think it is normal (for adults to go to the brothel), their wives do not know that, but for the medium to high income, not farmers.”

Northern male

Acceptance of a Minor Wife

Traditionally, in Thai society, a man may take a second, or minor wife. Acceptance of a second, minor wife was seen as problematic in some areas, but was reported to be more acceptable in the Southern area. If a man takes a minor wife, their may be emotional consequences for the first wife. In addition, because the man is expected to provide financial support for the minor wife, the family’s economic status may be affected.

“In our village, we have many older men who have a young minor wife but they live comfortably. We have many people like this. Most of the time, the wife will accept the situation because these males have high sexual needs and their wife cannot satisfy them, so they will find other young women to satisfy their needs. They don’t really love them, they just think of having sex.”

Southern male

Peer influence

Earlier research has stressed that peer influence is a strong determinant of male sexual behavior, at least for younger men (VanLandingham 1998). The older respondents in our study did not see peer influence as a strong factor. While they still socialized with their friends, they did not feel pressure to have sex with commercial partners. However, no one reported being pressured not to have sex with commercial partners. Sex with commercial partners was seen to be an individual choice. These comments showed the role of agency in personal decisions.

“I think they (my friends) are indifferent. I usually go to the café on weekends. I go to drink and listen to the music. My friends know that I go there to relax; I don’t go to the girl. It depends on the individual.”

Bangkok male

Condom use

The interview guide included questions on the appropriateness of condoms with different types of partners and the views of community members of older persons purchasing and carrying condoms. The respondents reported that condoms were not normally used among married couples, but that it was important for the man to use a condom if he had sex with other partners. Condoms were necessary with other partners due to the threat of HIV infection.

“Yes they should use (condoms) when they have sex with others … I think a condom is a necessary thing. Sex has to be protected.”

Bangkok male

“Mostly, people who are poor will not use condoms much because they think it is not natural. I think it is safe but we are not promiscuous.”

Southern male

“It is good to use a condom because if we get a disease, our family will become poor.”

Northern male

Summary and Discussion

Both male and female respondents were aware of a decreasing frequency of sex in marital relationships among persons in their 50s and most agreed that women had less desire for sex than men. The responsibilities for family and work at midlife as well a physical problems were an important reason for the declining frequency of sex. There was variation in how respondents adjusted to this change. Many said that they live as friends and spend more time at the temple. Some respondents stated that sex is important for an intimate marriage, but others thought that understanding each other, talking and taking care of each other maintained caring between partners.

For other persons, extramarital sex in the form of visits to sex workers or the taking of a minor wife was reported. There were a variety of opinions of the appropriateness of these behaviors and the acceptability of these behaviors in the community ranging from acceptance by the family and community to strong disapproval of these relationships. Although earlier research had noted some tolerance for extramarital partners, this cohort of adults experienced an HIV epidemic that included a strong prevention program (Rojanapithayakorn & Hanenberg, 1996). This experience may have made their views of extramarital partners mode conservative. In general, there were not clear regional differences in the sample. The one exception to this was that Bangkok males were more accepting of commercial partners. Living in a large city, use of sex workers can be concealed more easily from others

The study has some limitations. Results are based on a small sample that may not be representative of the views of the Thai population as a whole. The data also concern sensitive topics and responses cannot be verified. Earlier research (Knodel and Chayovan 2001), noted that women may underreport sexual activity relative to men, and that may also be a factor here. In addition, we interviewed only married persons and those who may have divorced due to problems with sexuality at midlife were not included.

Another limitation is the cross sectional nature of the study. Women and men may move through a series of stages that change over midlife including denial, anger, and bargaining that lead to different types of adjustment over time. A longitudinal study of this stage of life may shed more light on this process, and would be the next step in furthering research in this area.

Some of these results can be interpreted in relation to life course theory. The cohort studied in this research has lived through the emergence and continued presence of an HIV epidemic. This experience is reflected in the concerns about infection from extramarital partners and the need for condom use in these relationships. Changing sexual norms in Thailand, may also have affected the view of extramarital sex, although individuals have a sense of agency and make their own decisions about these matters.

Consistent with previous research (Knodel and Chayovan 2001), respondents generally viewed female desire for sexual activity as declining more quickly than male desire. Many thought that sexual activity should end in the sixties, but others thought that it should depend on the couple’s health.

In contrast to earlier research on peer influence and male sexual activity with a younger sample of men (VanLandingham et al. 1998; VanLandingham and Knodel, 2007), the older men in this study did not report strong peer pressure for extramarital activity. Within peer groups, decisions about sexual activity were an individual matter. Men were not pressured to engage in commercial sex, though there were no reports of men pressuring other not to have such relationships.

Although there was acknowledged decline in activity, the need for physical intimacy in the marriage was seen as important by many Thai respondents Some thought that this could be replaced by hugging, touching and caring for each other but for others, having sex was an important part of being a couple. This result is consistent with studies from other countries including Japan, the US, Germany and Brazil that sexual desire has importance among older adults (Heiman et al., 2011; Carpenter, Nathanson & Kim, 2009; Moore, 2010; Gott & Hinchliff, 2003). .

The influence of Buddhism on Thai attitudes and behavior concerning sexuality was evident in the responses of these Thai men and women. Spending more time at the temple and having more involvement in temple activities was an important way to deal with changes related to the aging process. This finding is consistent with a large literature that indicates that religion is beneficial to a sense of well being and is related to positive health behaviors (Chatters 2000; Ellison and Levin, 1998). Further research in this area could take a more indepth look at the place of spirituality in the lives of couples at midlife in Thailand

In summary, older Thai adults were aware of the changes in sexual activity in their age group and the differences by gender in sexual desire and activity. Many respondents reported that with advancing age, although sexual frequency may change, sexual activity was still important to a marriage. The experience of the AIDS epidemic may have made these adults more cautious about sexual activity with additional partners and more concerned about condom use. Views of the acceptability of additional sexual partners varied among adults in the study, though most reported that additional partners would cause problems. Buddhism and family activities were seen as an important resource for dealing with changes in sexual activity due to aging.

References

- Bachmann GA, Lieblum SR. The impact of hormones on menopausal sexuality: A literature review. Menopause. 2004;11:120–130. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000075502.60230.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee S, Leventhal H, Leventhal lE. Regulation, self regulation, and construction of the self in the maintenance of physical health. In: Boekarts M, Pintrich P, editors. Handbook of Self Regulation. London: Academic; 2000. pp. 369–415. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM, Nathanson CA, Kim YJ. Physical women, emotional men: Gender and sexual satisfaction in midlife. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:87–107. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamratrithirong A, Kittisuksakit S, Podhisita C, Isarabhakdi P, Sabalying M. National Sexual Behavior Survey of Thailand. Nakhon Pathom: Institute for Population and Social Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM. Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Elder GH. Successful Adaptation in the Later years: A Life Course Approach to Aging. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2002;65:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. Life course dynamics: Trajectories and transition, 1968–1980. Ithace, NY: Cornell University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. The life course as development theory. Child Development. 1998;69:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin GS. Successful adaptation in later years: A life course approach to aging. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1998;65:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Chamratrithirong A. First sexual experience and current sexual behavior among older Thai men and women. Sexual Health. 2009;6:195–202. doi: 10.1071/SH08049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott M, Hinchliff S. How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:1617–1628. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman FR, Long JS, Smith SN, Fisher WA, Sand MS, Rosen RC. Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9703-3. Published online 26 January 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im-Em W, VanLangingham M, Knodel J, Saengtienchai C. HIV/AIDS related knowledge and attitudes: A comparison of older persons and young adults in Thailand. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(3):246–262. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.3.246.23889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J, VanLandingham M, Saengtienchai C, Pramularatana A. Thai view of sexuality and sexual behavior. Health Transition Review. 1996;6:179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J, Chayovan N. Sexual activity among older Thais: The influence of age, gender and health. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology. 2001;16:173–200. doi: 10.1023/a:1010608226594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O'Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KL. Sexuality and sense of self in later life: Japanese men’s and women’s reflections on sex and aging. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology. 2010;25:149–163. doi: 10.1007/s10823-010-9115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Moreira ED, Jr, Paik A, Gingell C. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: The global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology. 2004;64:991–997. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojanapithayakorn W, Hanenberg R. The 100% condom use program in Thailand. AIDS. 1996;10:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe L, Curran L. Understanding the process of adjustment to illness. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanLandingham M, Knodel J, Saengtienchai C, Pramualratana A. In the company of friends: Peer influence on Thai male extramarital sex. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:1993–2011. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanLandingham M, Knodel J. Sex and the (single) older guy: Sexual lives of older unmarried Thai men during the AIDS era. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology. 2007;22:375–388. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]