Abstract

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is an uncommon tumor affecting adolescents and young adults that is only rarely encountered in body fluid cytology. We report the cytological features of metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in the ascitic fluid of a 17-year-old female patient, who had presented with abdominal distention, 21 months after being diagnosed with perirectal alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. The rare single neoplastic cells that were admixed with abundant reactive mesothelial cells were initially misinterpreted as reactive mesothelial cells. However, their neoplastic nature was established after a careful review of their cytological features and the performance of immunoperoxidase stains. Compared to the reactive mesothelial cells that were present in the sample, the malignant cells were smaller, with less ample and more homogenous cytoplasm. They had slightly larger, more hyperchromatic, and more frequently eccentric nuclei, with larger nucleoli. This case highlights the potential pitfall of the misinterpretation of metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells for reactive mesothelial cells. Awareness of this potential diagnostic problem and recognition of the cytomorphological features of this neoplasm in the body fluids allows the identification of malignant cells, even when they are rare and intimately associated with mesothelial cells.

Keywords: Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, cytology immunohistochemistry, peritoneal fluid

INTRODUCTION

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARM) was originally described by Riopelle and Theriault in 1956,[1] and confirmed by Enterline and Horn in 1958.[2] In 1969, Enzinger and Shiraki [3] reported a study on 110 cases of ARMs and established that most of these tumors occurred in patients who were 10-20 years of age, and most commonly arose in the extremities or the perirectal and perianal areas. It is now known that ARMs are characterized by specific and recurring chromosomal abnormalities that include t(2;13)(q35;q14), resulting in the fusion gene PAX3-FOXO1, in 75% of the fusion-positive ARMs cases.[4] Experience with cytology of rhabdomyosarcomas (RMS) is largely limited to fine needle aspiration samples and touch imprints. Although according to some authors sarcomas may represent up to 5% of all malignant effusion specimens,[5] malignant effusions are rare in rhabdomyosarcoma patients, and experience with the cytological features of RMS in effusions is limited.[6–8] We herein present a case of metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosed on cytological examination of the ascites fluid and discuss the diagnostic difficulties that were encountered in this case.

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old female patient presented with increasing abdominal discomfort in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and abdominal distention due to ascites. A paracentesis was performed and fluid was submitted for chemical and cytological evaluation. Laboratory evaluation of the peritoneal fluid showed glucose of 85 mg/dl, total protein of 4.1 g/dl, and fluid albumin of 2.2 g/dl. Twenty-one months prior to the current presentation, the patient was admitted to the hospital with increasing perirectal pain and an enlarging mass, which on a computed tomography (CT) scan was seen to be located between the posterior margin of the anus and the gluteal crease. The CT scan also revealed bilateral inguinal, iliac, and subcarinal lymphadenopathy, along with four masses in her right lung. An excisional lymph node biopsy was performed and a diagnosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma was rendered, based on the cytomorphology and immunophenotype. G-banded karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies revealed a FOXO1 locus rearrangement of t(2;13)(q36,q14) in the background of a near-tetraploid karyotype, with multiple other abnormalities.

Cytological findings

Wright-stained cytospin preparations, Papanicolaou-stained Surepath® preparations, and hematoxlin and eosin-stained cellblock preparations were made from the peritoneal fluid. All preparations showed abundant mesothelial cells, lymphocytes, and occasional neutrophils. Rare, tight, three-dimensional clusters of 10 to 20 cells were present in the Papanicolaou-stained preparation. All preparations showed small-to-very large single cells, with single or multiple hyperchromatic nuclei, and high nucleocytoplasmic ratios. No mitoses or necrosis was seen. The neoplastic cells were typically seen intimately associated with mesothelial cells and inflammatory cells, forming mixed cell clusters. This dyshesive, polymorphous population of cells was most easily appreciated in the Wright-stained cytospin preparations [Figure 1], where the cells were rounded-to-ovoid, and ranged from small (mean, 18 μm) to large (mean, 22 μm) in size. The nuclei of the larger cells were ovoid and measured 18 × 13 μm on an average. Some of the cells showed prominent nucleoli, which were frequently irregular in shape, and ranged in size from 3.5 to 6 μm. In the same Wright-stained preparation, the mesothelial cells were larger (mean, 25 × 22 μm), but their nuclei (mean, 12 μm in diameter) and nucleoli (mean, 3 μm) were smaller than those of the neoplastic cells. The nucleocytoplasmic ratio of mesothelial cells was also lower compared to that of the tumor cells. The cytoplasm of the tumor cells ranged from scant rims of bluish, dense, non-vacuolated cytoplasm to a more ample, eccentric cytoplasm, with perinuclear metachromatic pink-staining areas. The tumor cells were slightly smaller in the Papanicolaou-stained preparation, where the nuclear details were better appreciated. The nuclei were coarsely hyperchromatic with thick chromatinic rims and had single to multiple irregularly shaped nucleoli. The cytoplasm appeared dense, glassy, and cyanophilic, occasionally with pink hues. Multilobated and multinucleated cells were easily identified, sometimes with ‘wreath-like’ eccentrically located nuclei. Large, pleomorphic cells, measuring up to 30 μm, were also present [Figure 2]. Some nuclei had irregular, ‘nose-like’ protrusions and some had complex, convoluted ‘embryo-like’ shapes. Occasional pairs of tumor cells separated by apparent ‘windows’ were present and mimicked the mesothelial cells.

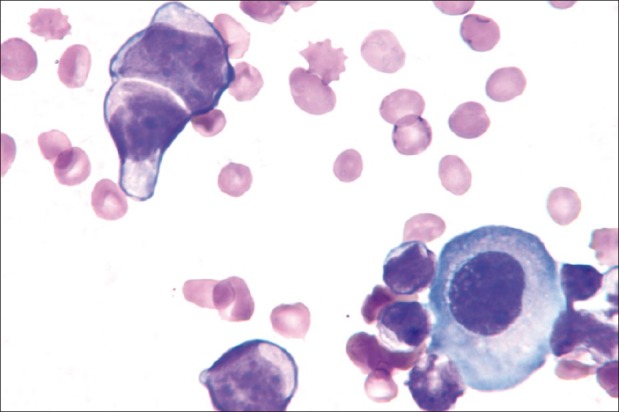

Figure 1.

A pair of neoplastic cells (upper left) shows scant cytoplasm, irregular nuclear contours, visible small nucleoli, and a possible inter-cellular ‘window’. The cytoplasmic eosinophilia of the neoplastic cells contrast with the cytoplasmic basophilia of the larger reactive mesothelial cell (lower right) (Wright stain, ×1000)

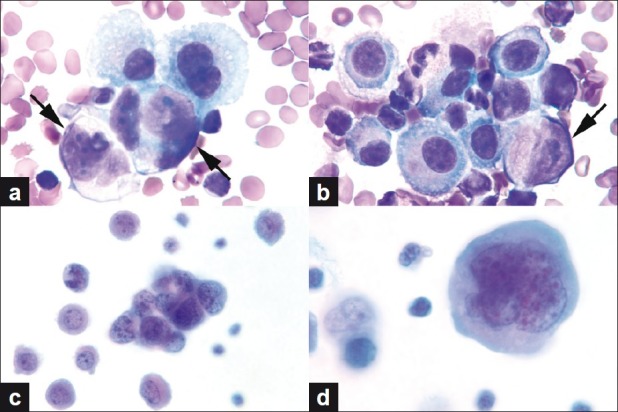

Figure 2.

(a, b) Neoplastic cells (arrows) intermixed with reactive mesothelial cells. Note the eccentric location of the nuclei of neoplastic cells. (c) Tight 3D cluster of small undifferentiated tumor cells. (d) Multilobated / multinucleated, large, pleomorphic tumor cell with dense cytoplasm (a, b. Wright stain, c, d. Papanicolaou stain, all images original magnification, ×1000)

Cell-block sections showed pleomorphic tumor cells, with high nucleocytoplasmic ratio, coarse hyperchromatic nuclei, and prominent nucleoli [Figures 3a and 3b]. Occasional cells with plasmacytoid appearance and eosinophilic cytoplasm were present. No strap cells or classic rhabdomyoblasts were seen.

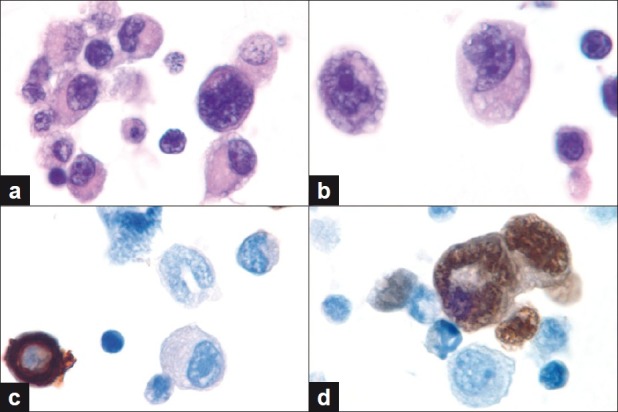

Figure 3.

(a, b) Cell block findings showing neoplastic cells admixed with reactive mesothelial cells and lymphocytes. Note the hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli of the neoplastic cells. (c, d) Immunoperoxidase studies for cytokeratin AE1 / AE3 and myogenin show lack of tumor cell staining for CK and nuclear positivity for myogenin. Mesothelial cells show the opposite staining pattern. (a,b: Hematoxylin and Eosin, c,d: Immunoperoxidase stains, all images original magnification, ×1000)

The cytological features of the peritoneal fluid were initially interpreted as atypical, favoring the reactive mesothelial cells; however, on review of the case by the cytopathologist, they were considered malignant, and immunoperoxidase stains were performed to confirm the diagnosis. Immunoperoxidase stains performed on the cellblock preparation showed that the neoplastic cells were positive for muscle-specific actin and myogenin [Figure 3d], but were negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 [Figure 3c]. Both the reactive mesothelial cells and neoplastic cells were strongly positive for desmin. A diagnosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma involving the peritoneal fluid was made based on the cytomorphology and immunoperoxidase stain results.

DISCUSSION

The exfoliative cytology of rhabdomyosarcomas in body fluids has not been described in detail. However, FNA studies have shown that the cytomorphology of rhabdomyosarcomas is characterized by the presence of a dual cell population; the first cell type is small, non-descript, with scant cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli, and resembles large lymphocytes, and a more differentiated second population is of rhabdomyoblasts with distinctive cytological features. These include ‘strap-cells’ with cross-striations, reflecting myotubule differentiation, ‘tadpole’ or ‘ribbon-shaped’ cells with abundant, deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm.[9] Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas and embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas differ in the relative proportion of more differentiated, distinctive rhabdomyoblastic cells. Such cells are common in embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas and may be completely absent in ARM. ARM has been reported to show more frequent binucleated or giant multinucleated cells, alveolar structures, mitotic figures, and prominent cytonuclear atypia.[10] Rosettes may occasionally be seen in ARM. Due to the predominance of the small undifferentiated cells in ARM, the cytological diagnosis is more difficult and and misinterpretation as hematolymphoid neoplasms is not uncommon, especially when metastatic to the bone marrow or lymph nodes. Similar to our experience, the authors of a recent case report encountered difficulties in differentiating rhabdomyosarcomas from reactive mesothelial cells.[8]

The differential diagnosis between mesothelial cells and malignant cells (including RMS cells) may be difficult, especially in malignancies that present with single, dissociated cells, rare malignant cells and relatively small cells, in a background of abundant reactive mesothelial cells. While the cytological diagnosis of metastatic malignancy in effusions generally relies on the detection and confirmation of a ‘second-foreign’ non-inflammatory, non-mesothelial population of cells,[11] some malignancies may shed cells into fluids that mimic some of the features of reactive mesothelial cells, including their characteristic ‘windows’, further compounding the diagnostic challenge in identifying them. The case presented herein shows all of these features, presenting with relatively small dissociated cells, with some mesothelial-like cytological features in a background of abundant mesothelial cells, which helps explain the initial difficulty encountered in identifying the malignant cells. In addition, the mesothelial cells also showed a spectrum of reactive atypia and multinucleation, as frequently seen in patients who have undergone chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, further increasing the diagnostic difficulties in identifying the neoplastic cells. As in the case of other metastatic malignancies that are only rarely encountered in effusion cytology,[12] the diagnosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is also challenging, due to the cytologists’ lack of familiarity with its cytological features. Although the age of the patient, clinical presentation, and history are all helpful in the differential diagnosis, ancillary studies, including immunocytochemistry, cytogenetics or molecular studies are frequently needed to establish an accurate definitive diagnosis.

Immunohistochemical stains are frequently used to confirm and highlight a ‘second-foreign’ population of malignant cells in effusions. The choice of the panel of immunostains used depends on the suspected second (malignant) cell population. In the case of rhabdomyosarcoma such a panel would include stains for vimentin, desmin, and myogenin, but the staining results may be confusing, as reactive mesothelial cells are also typically positive for vimentin[11] and desmin.[13] In contrast, nuclear myogenin staining can serve as a reliable marker for rhabdomyosarcoma, as it has not been reported in mesothelial cells[14] or in other small round cell tumors that may also be encountered in effusion cytology, and have to be considered in the differential diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma, including desmoplastic small round cell tumor[15] (a tumor that also frequently expresses desmin[16]), Ewing sarcoma / primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and other sarcomas,[17] lymphomas, neuroblastomas, and neuroendocrine carcinoma. However, as myogenin staining may be present in only a small fraction of the neoplastic cells, [17] absence of myogenin staining does not rule out rhabdomyosarcoma, especially in cases in which only rare malignant cells are present in the specimen. In such cases, a ‘subtractive coordinate immunoreactivity pattern’ approach[11] or a ‘two-color’ immunostaining technique, combining desmin (which is positive in both mesothelial cells and rhabdomyosarcoma cells) with wide-spectrum cytokeratin or cytokeratin 7 (which are positive only in mesothelial cells) can be applied, using an approach similar to that proposed by Shidham et al., for metastatic adenocarcinomas.[11]

As alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas frequently harbor characteristic chromosomal translocations resulting in chimeric fusion proteins, fluorescence in situ hybridization, [18] and/or molecular studies[19] can be used, in addition to immunohistochemistry, to confirm the presence of rhabdomyosarcoma cells in effusions. A recent study used reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to demonstrate the presence of a PAX / FKHR (PAX / FOX1) fusion mRNA in the pleural fluid of a 14-year-old male patient, who presented with a large left retroperitoneal mass accompanied by pleural effusion and showed malignant small round blue cells that were positive for vimentin, actin, desmin, MyoD1, myogenin, and CD56, in effusion cytology.[20]

CONCLUSION

We present an unusual case, in which metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma was initially ‘missed’ on cytological examination of the ascitic fluid, as the neoplastic cells were misinterpreted as reactive mesothelial cells. However, careful examination of the cytological preparations and the application of immunostains established an accurate diagnosis. Comparison between the ARM cells and the reactive mesothelial cells present in the preparations showed that the neoplastic cells were smaller, but had slightly lager nuclei, and therefore, higher nucleocytoplasmic ratios, had larger nucleoli and coarser chromatin. In addition, as opposed to mesothelial cells, they failed to show a two-zone demarcation of the cytoplasm or a ‘frilly’ cell border and frequently showed eccentric nuclei.

Awareness of the rare occurrence of neoplastic cells of an alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in body fluids and familiarity with their cytological appearance can help the cytologist identify them and perform confirmatory immunostains and/or a cytogenetic or molecular test, and thereby avoid the misinterpretation of neoplastic cells as reactive mesothelial cells.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

There is no competing interest to declare by any of the authors.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the study and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. Each author acknowledges that this final version has been read and approved by them.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report without patient identifiers, approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) is not required at our institution.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2012/9/1/9/94569.

Contributor Information

Andrew C. Nelson, Email: nels2055@umn.edu.

Charanjeet Singh, Email: singh114@umn.edu.

Stefan E. Pambuccian, Email: pambu001@umn.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riopelle JL, Theriault JP. An unknown type of soft part sarcoma: alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Ann Anat Pathol (Paris) 1956;1:88–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enterline HT, Horn RC., Jr Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma; a distinctive tumor type. Am J Clin Pathol. 1958;29:356–66. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/29.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enzinger FM, Shiraki M. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma.An analysis of 110 cases. Cancer. 1969;24:18–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196907)24:1<18::aid-cncr2820240103>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu Z, Kelsey A, Alaggio R, Parham D. Clinical utility gene card for: Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.147. [In Press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chivukula M, Saad R. Metastatic sarcomas, melanoma, and other non-epithlial neoplasms. In: Shidham VB, Atkinson BF, editors. Cytopathologic Diagnosis of Serous Fluids. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajdu SI, Koss LG. Cytological diagnosis of metastatic myosarcomas. Acta Cytol. 1969;13:545–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abadi MA, Zakowski MF. Cytological features of sarcomas in fluids. Cancer. 1998;84:71–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980425)84:2<71::aid-cncr1>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiryayi SA, Rana DN, Roulson J, Crosbie P, Woodhead M, Eyden BP, et al. Diagnosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in effusion cytology: a diagnostic pitfall. Cytopathology. 2010;21:273–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2009.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castelino-Prabhu S, Ali SZ. “Strap cells” in primary prostatic rhabdomyosarcoma in a child. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:505–6. doi: 10.1002/dc.21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klijanienko J, Caillaud JM, Orbach D, Brisse H, Lagace R, Vielh P, et al. Cyto-histological correlations in primary, recurrent and metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: the institut Curie’s experience. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:482–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shidham VB, Varsegi G, D’Amore K. Two-color immunocytochemistry for evaluation of effusion fluids for metastatic adenocarcinoma. Cytojournal. 2010;7:1. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.59887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne MM, Rader AE, McCarthy DM, Rodgers WH. Merkel cell carcinoma in a malignant pleural effusion: case report. Cytojournal. 2004;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasteh F, Lin GY, Weidner N, Michael CW. The use of immunohistochemistry to distinguish reactive mesothelial cells from malignant mesothelioma in cytological effusions. Cancer cytopathology. 2010;118:90–6. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afify AM, Al-Khafaji BM, Paulino AF, Davila RM. Diagnostic use of muscle markers in the cytological evaluation of serous fluids. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2002;10:178–82. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200206000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang PJ, Goldblum JR, Pawel BR, Fisher C, Pasha TL, Barr FG. Immunophenotype of desmoplastic small round cell tumors as detected in cases with EWS-WT1 gene fusion product. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:229–35. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000056630.76035.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granja NM, Begnami MD, Bortolan J, Filho AL, Schmitt FC. Desmoplastic small round cell tumour: Cytologicalal and immunocytochemical features. Cytojournal. 2005;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morotti RA, Nicol KK, Parham DM, Teot LA, Moore J, Hayes J, et al. An immunohistochemical algorithm to facilitate diagnosis and subtyping of rhabdomyosarcoma: the Children’s Oncology Group experience. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:962–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200608000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishio J, Althof PA, Bailey JM, Zhou M, Neff JR, Barr FG, et al. Use of a novel FISH assay on paraffin-embedded tissues as an adjunct to diagnosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Lab Invest. 2006;86:547–56. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wexler LH, Ladanyi M. Diagnosing alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: morphology must be coupled with fusion confirmation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2126–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawangpanich R, Larbcharoensub N, Jinawath A, Pongtippan A, Anurathapan U, Hongeng S. Detection of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in pleural fluid with immunocytochemistry on cell block and determination of PAX / FKHR fusion mRNA by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:1394–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]